Deep Reinforcement Learning for Optimized Reservoir Operation and Flood Risk Mitigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

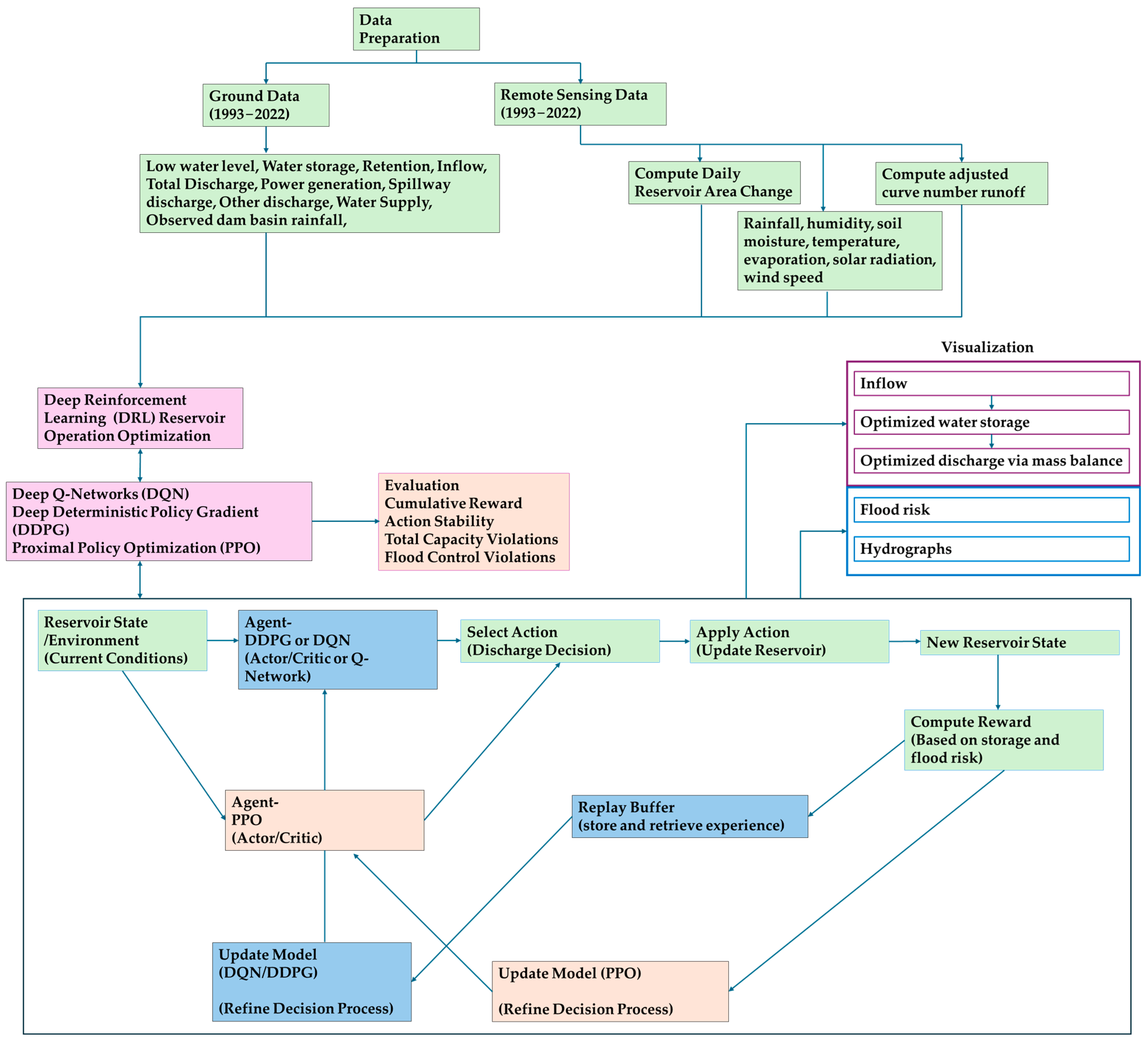

2. Materials and Methods

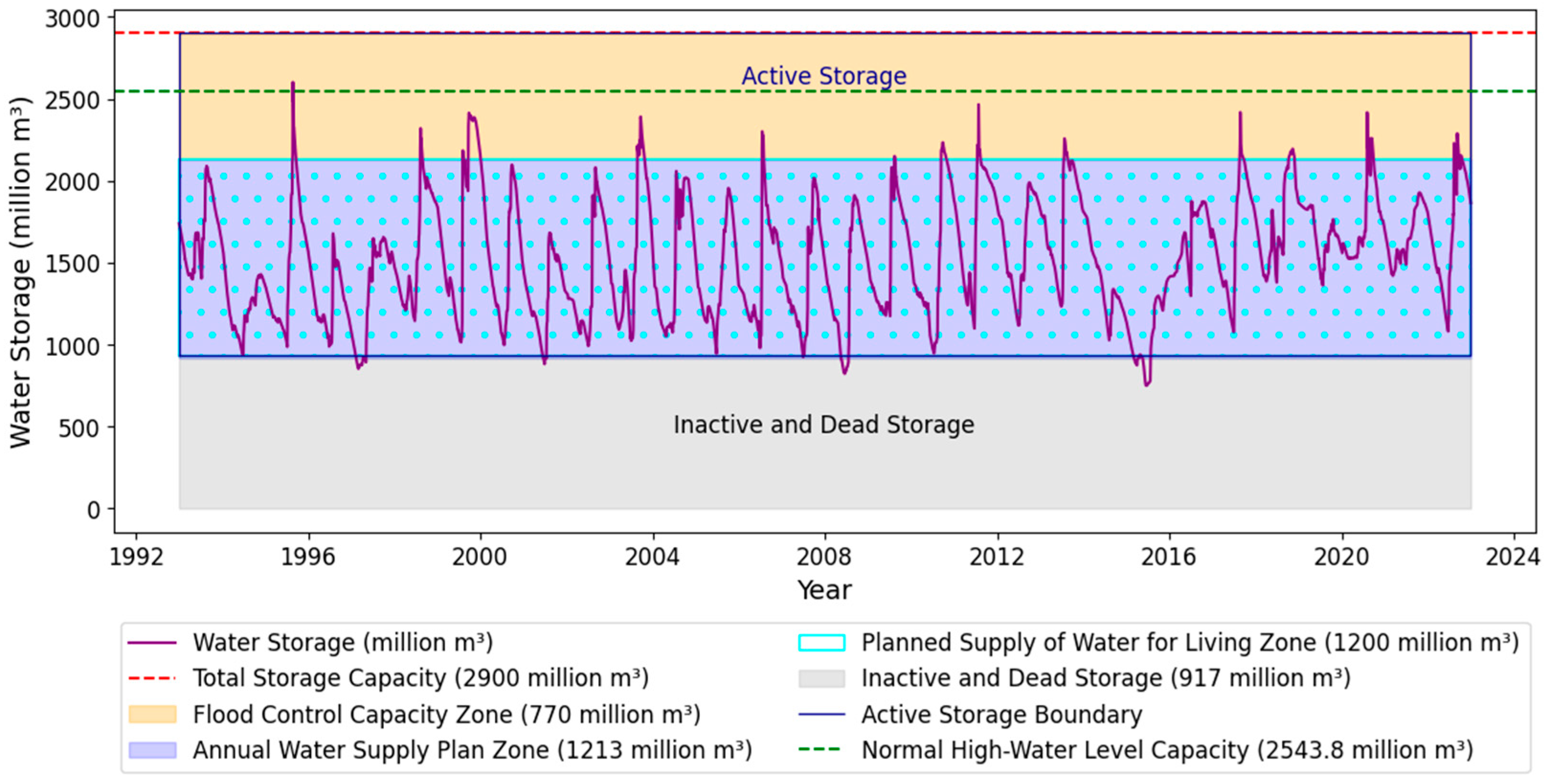

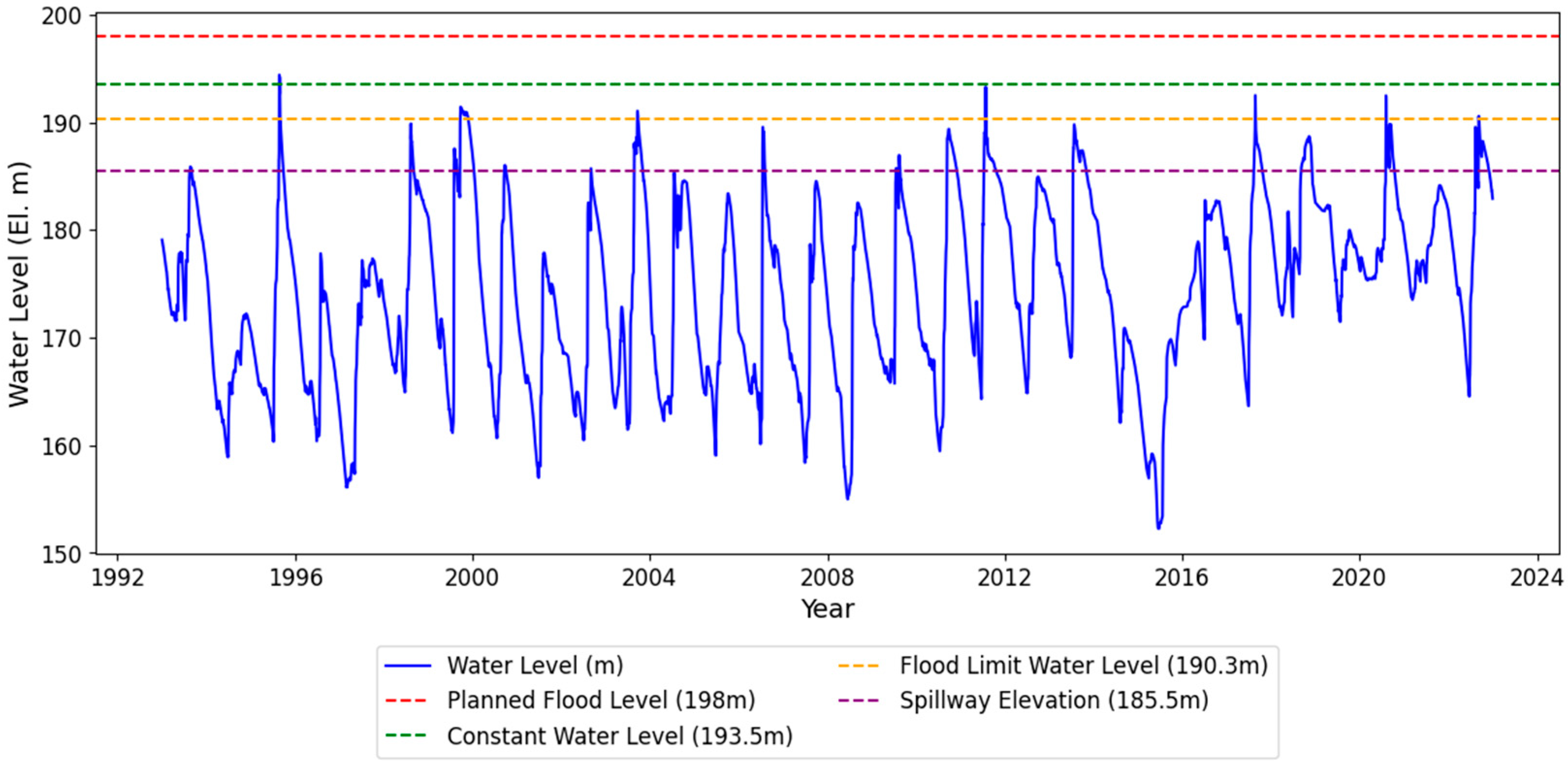

2.1. Study Area

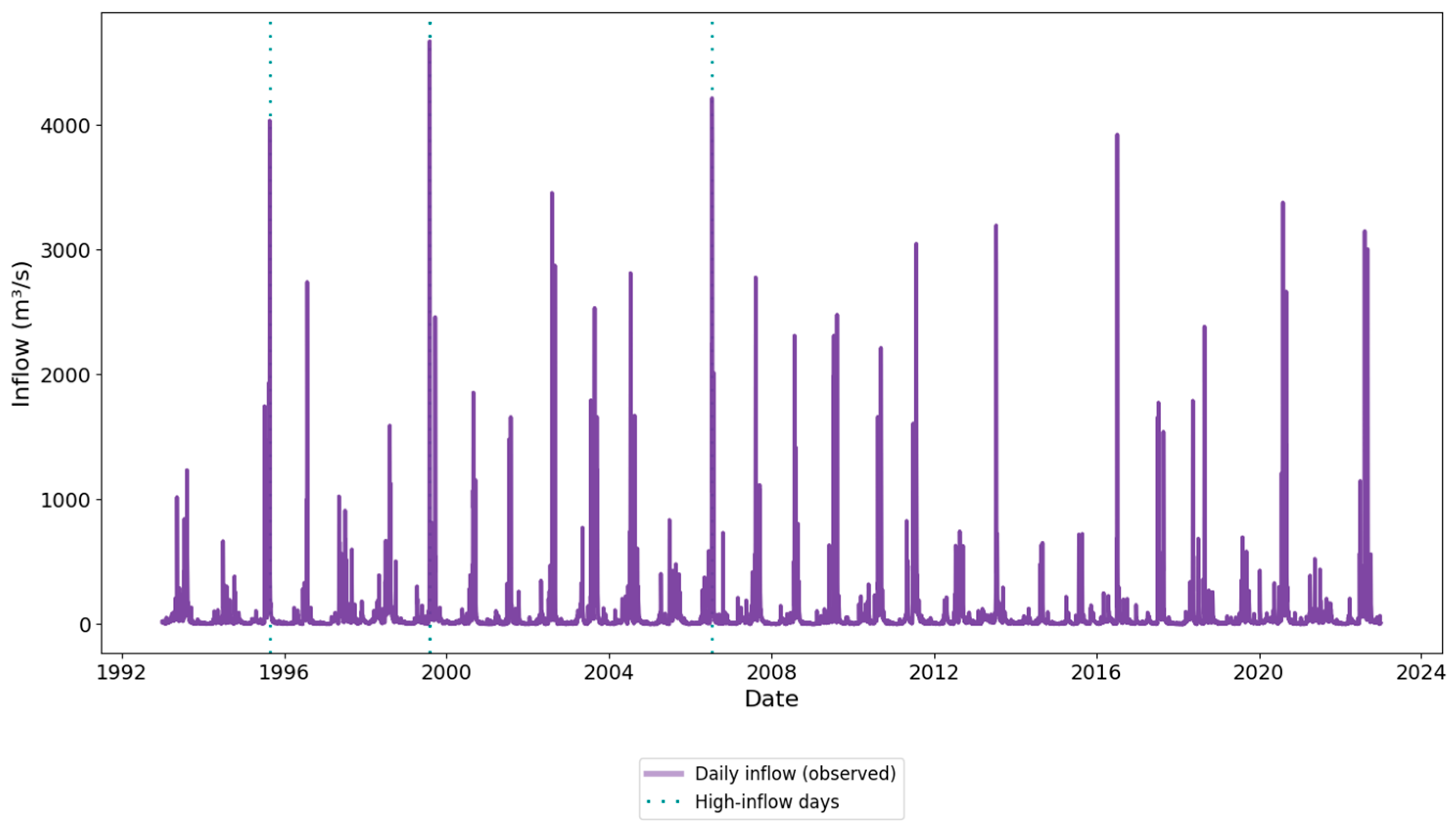

2.2. Data Used

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Deep Reinforcement Learning Models

2.3.2. Action Stability Metric

3. Results

3.1. Performance Evaluations

Performance Evaluation of DQN, PPO, and DDPG Deep Reinforcement Learning Models

3.2. Deep Reinforcement Learning Model Results

3.2.1. Inflow over Time for the Soyang Reservoir

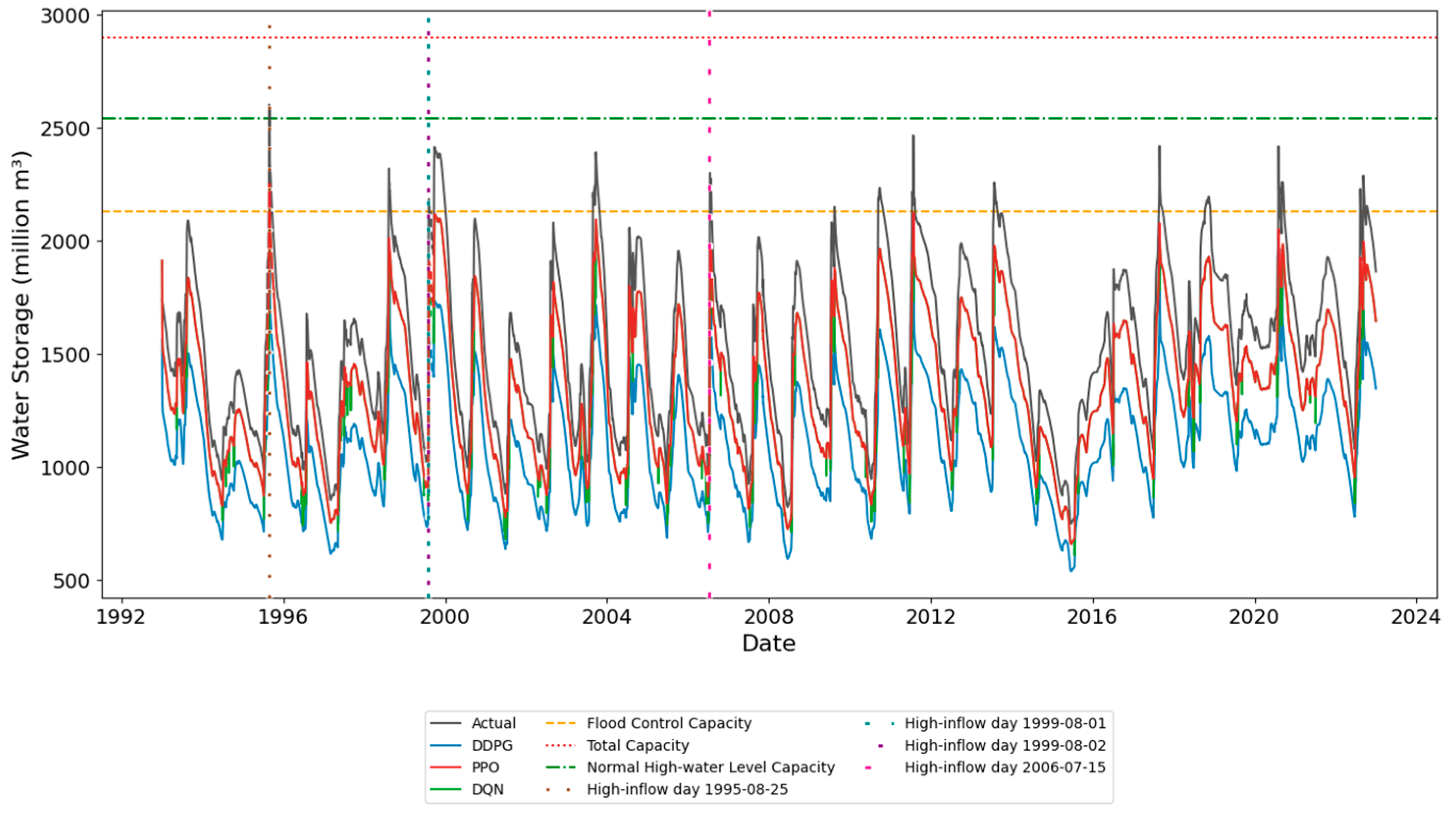

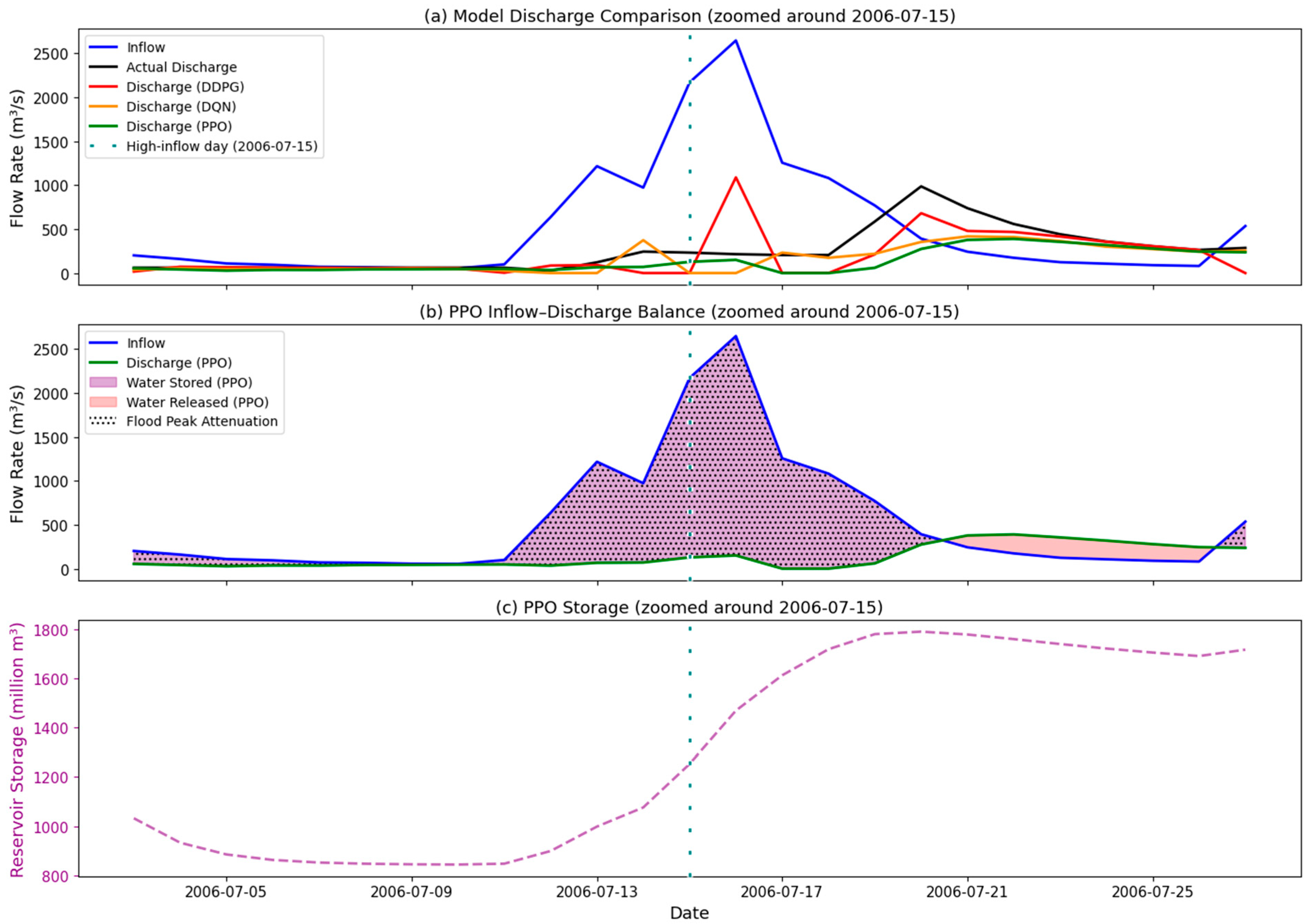

3.2.2. Water Storage over Time Based on DDPG, PPO, and DQN

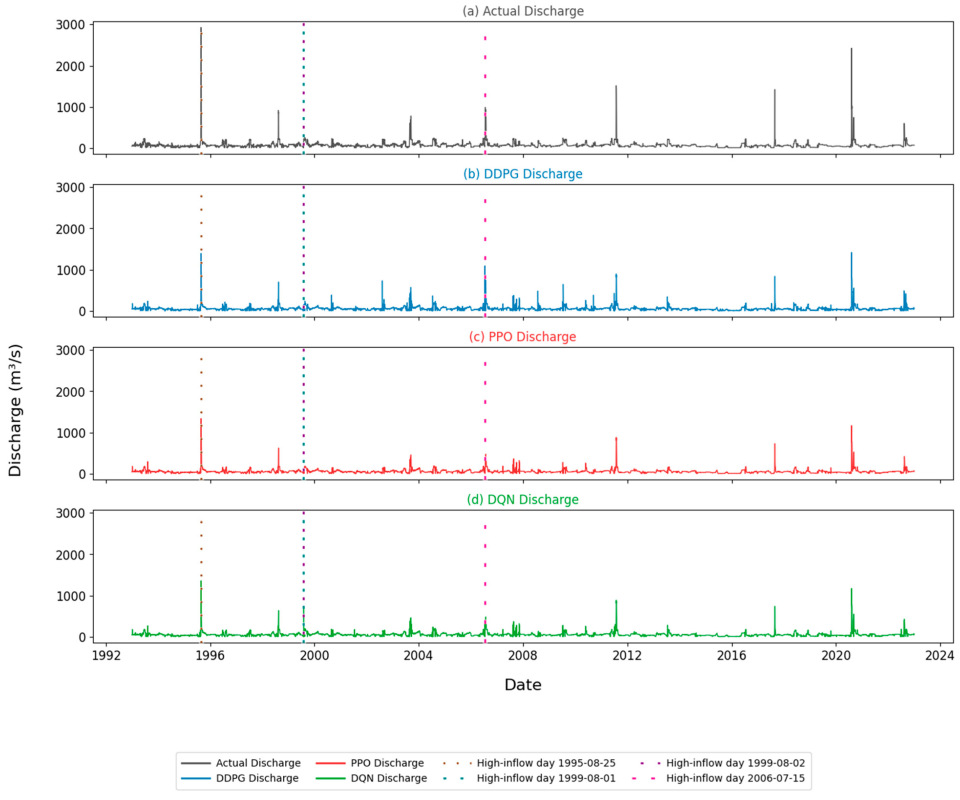

3.2.3. Water Discharge over Time Based on DDPG, PPO, and DQN

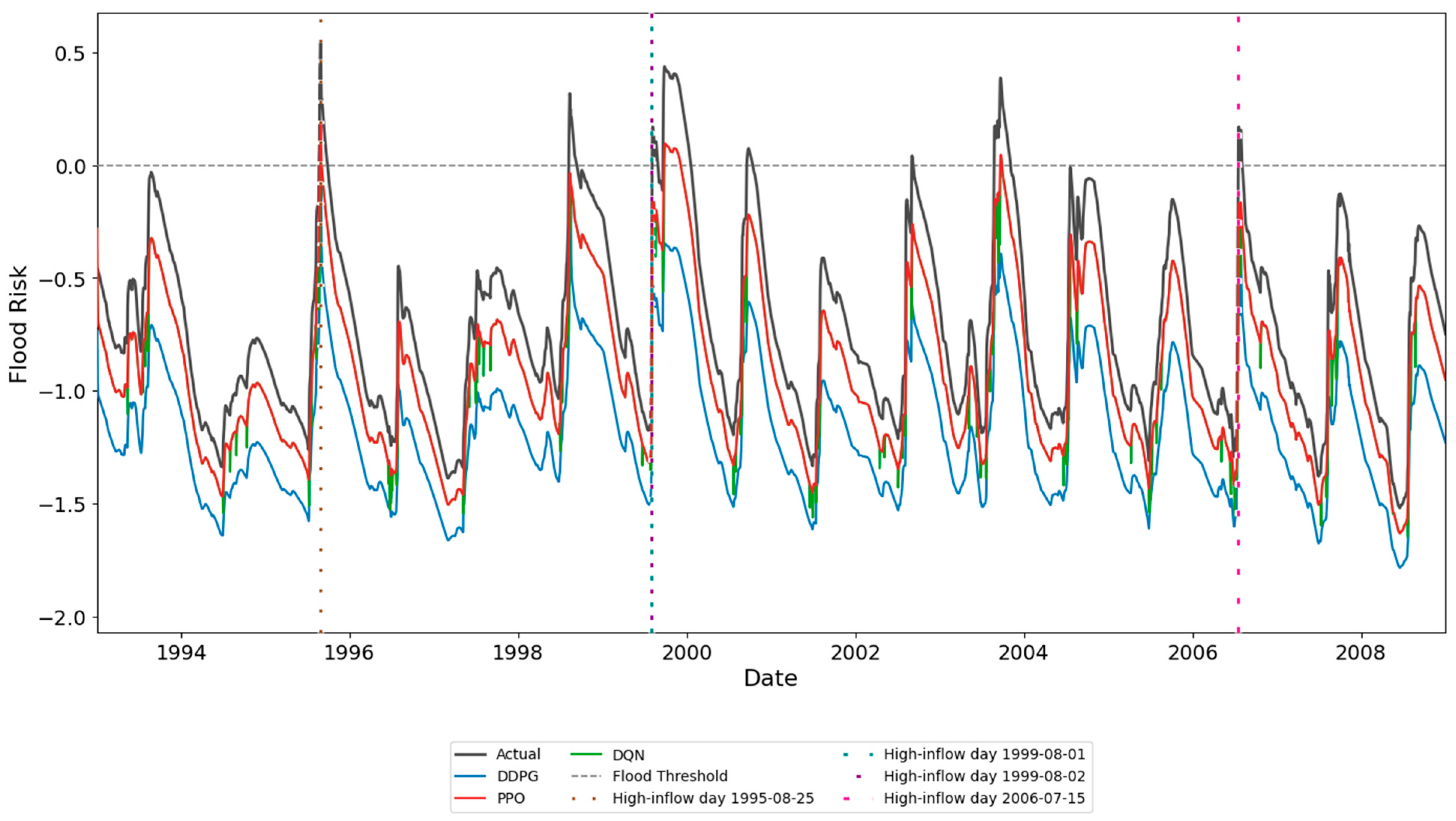

3.2.4. Flood Risk Based on DDPG, PPO, and DQN

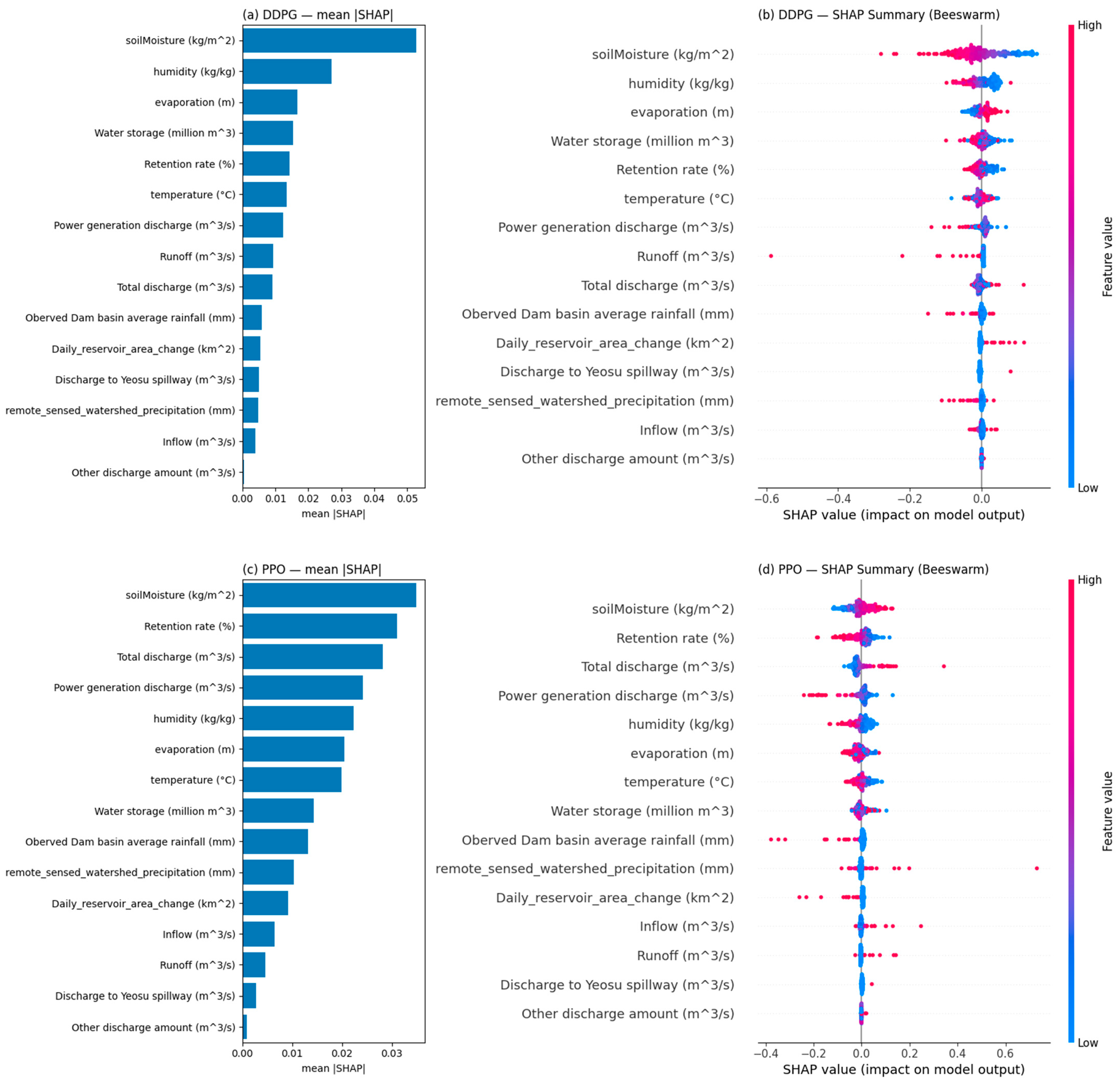

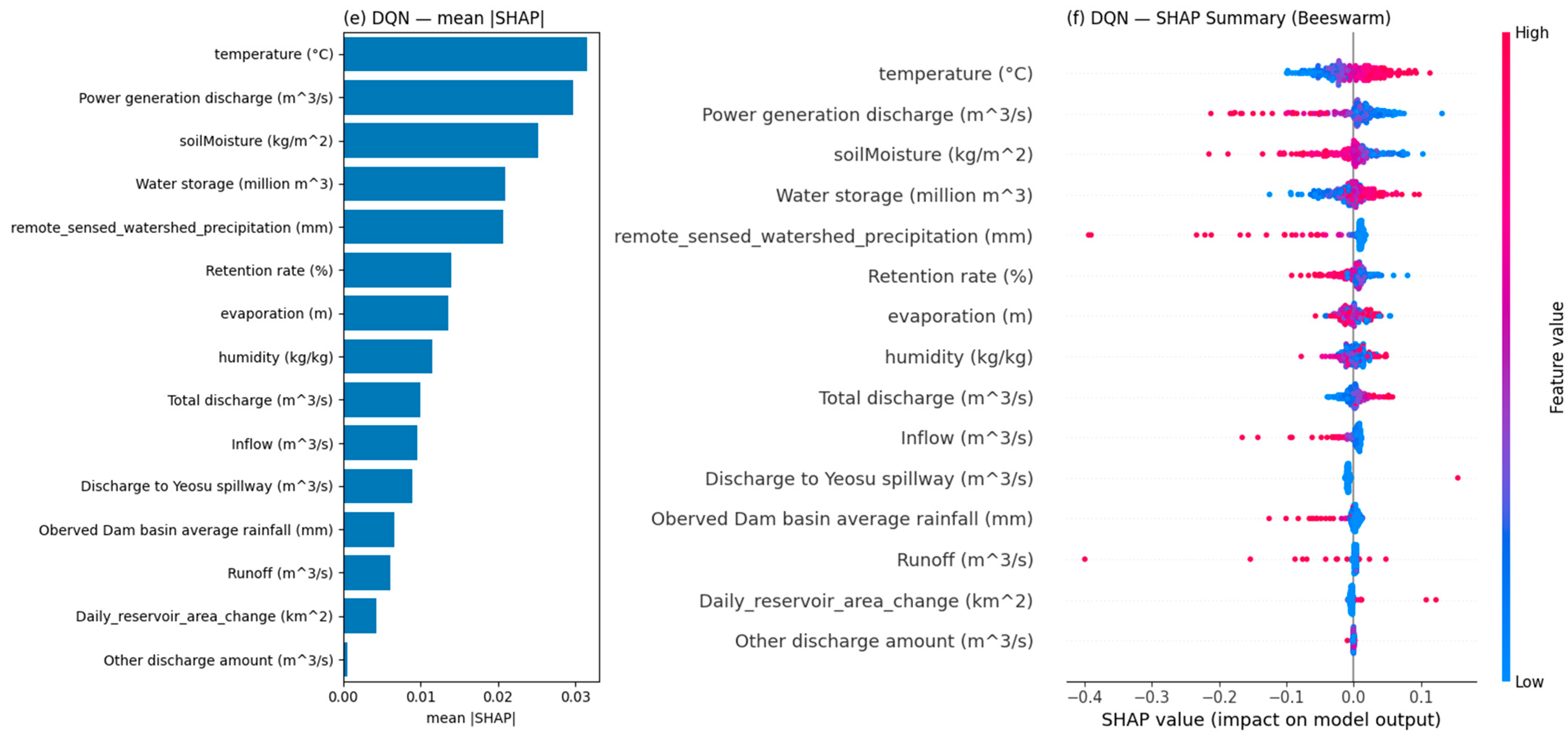

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bakis, R. Electricity Production Opportunities from Multipurpose Dams (Case Study). Renew. Energy 2007, 32, 1723–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xu, Y.P.; Gu, H.; Guo, Y. Multi-Objective Robust Optimization of Reservoir Operation for Real-Time Flood Control under Forecasting Uncertainty. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.M.; Frazier, T.G. Deterministic and Probabilistic Flood Modeling for Contemporary and Future Coastal and Inland Precipitation Inundation. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 50, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zhong, P.-A.; Xu, B.; Zhu, F.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, S. Risk Analysis for Reservoir Flood Control Operation Considering Two-Dimensional Uncertainties Based on Bayesian Network. J. Hydrol. 2020, 589, 125353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahootchi, M.; Tizhoosh, H.R.; Ponnambalam, K.P. Reservoir Operation Optimization by Reinforcement Learning. J. Water Manag. Model. 2007, 8, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delipetrev, B.; Jonoski, A.; Solomatine, D. Optimal Reservoir Operation Policies Using Novel Nested Algorithms; European Geosciences Union: Munich, Germany, 2015; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Cheng, C.; Lund, J.R.; Niu, W.; Miao, S. Stochastic Dynamic Programming for Hydropower Reservoir Operations with Multiple Local Optima. J. Hydrol. 2018, 564, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, M.; Galelli, S.; Soncini-Sessa, R. A Dimensionality Reduction Approach for Many-Objective Markov Decision Processes: Application to a Water Reservoir Operation Problem. Environ. Model. Softw. 2014, 57, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Eamen, L.; Dandy, G.; Razavi, S.; Kuczera, G.; Maier, H.R. Beyond Engineering: A Review of Reservoir Management through the Lens of Wickedness, Competing Objectives and Uncertainty. Environ. Model. Softw. 2023, 167, 105777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, F.; Yang, Y.C.E. Assessing Adaptive Irrigation Impacts on Water Scarcity in Nonstationary Environments—A Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning Approach. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR029262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Huang, J.; Zou, R.; Ma, W.; Guo, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Deep-Reinforcement-Learning-Based Water Diversion Strategy. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnology 2024, 17, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Huang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C. A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach for Joint Scheduling of Cascade Reservoir System. J. Hydrol. 2025, 651, 132515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phankamolsil, Y.; Rittima, A.; Sawangphol, W.; Kraisangka, J.; Tabucanon, A.S.; Talaluxmana, Y.; Vudhivanich, V. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Multiple Reservoir Operation Planning in the Chao Phraya River Basin Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) Algorithm Artificial Intelligence (AI) Reservoir Operation Planning Chao Phraya River Basin. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Ahn, H.; Kang, H.; Jeon, D.J. Identification of Preferential Target Sites for the Environmental Flow Estimation Using a Simple Flowchart in Korea. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Peng, A.; Liang, Y. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Cascaded Hydropower Reservoirs Considering Inflow Forecasts. Water Resour. Manag. 2020, 34, 3003–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Bai, L.; Tian, W.; Yan, H.; Hu, W.; Xin, K.; Tao, T. Online Control of the Raw Water System of a High-Sediment River Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Water 2023, 15, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yan, Z.; Xuan, J.; Zhang, G.; Lu, J. Improving Proximal Policy Optimization with Alpha Divergence. Neurocomputing 2023, 534, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-H.; Kim, H.-A.; Cha, Y.; Do, H.-S.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Park, S.K.; Yoo, H.-D. Recent Changes in Summer Rainfall Characteristics in Korea. J. Eur. Meteorol. Soc. 2025, 2, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowes, B.D.; Tavakoli, A.; Wang, C.; Heydarian, A.; Behl, M.; Beling, P.A.; Goodall, J.L. Flood Mitigation in Coastal Urban Catchments Using Real-Time Stormwater Infrastructure Control and Reinforcement Learning. J. Hydroinformatics 2021, 23, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kåge, L.; Milić, V.; Andersson, M.; Wallén, M. Reinforcement Learning Applications in Water Resource Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Water 2025, 7, 1537868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Li, W.; He, M.; Zhang, T.; Chen, S.; Guan, W.; Hua, X.; Zheng, S. Research on Long-Term Scheduling Optimization of Water–Wind–Solar Multi-Energy Complementary System Based on DDPG. Energies 2025, 18, 3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Wang, B.; Chen, J.; Fan, Y.; Mo, R.; Xu, C.; Liu, W.; Liu, J.; Zhong, P. an An Explainable Ensemble Deep Learning Model for Long-Term Streamflow Forecasting under Multiple Uncertainties. J. Hydrol. 2025, 662, 133968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.; Kang, B. Comparative Study of Low Flow Frequency Analysis Using Bivariate Copula Model at Soyanggang Dam and Chungju Dam. Hydrology 2024, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J. Predicting Inflow Rate of the Soyang River Dam Using Deep Learning Techniques. Water 2021, 13, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K-water. 2018 Sustainability Report: Providing a Brighter, Happier, and More Prosperous Future with Water; Publication No. 2018-MA-GP-18-107; K-water: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2018; Available online: https://www.kwater.or.kr/web/eng/download/smreport/2018_SMReport.pdf?utm (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Kim, J.S.; Jain, S.; Kang, H.Y.; Moon, Y.I.; Lee, J.H. Inflow into Korea’s Soyang Dam: Hydrologic Variability and Links to Typhoon Impacts. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2019, 22, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J. An Assessment of Dam Operation Considering Flood and Low-Flow Control in the Han River Basin. Water 2021, 13, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Deng, C.; Wei, J.; Zou, J. Assessing the Impacts of Climate Change and Land Use/Land Cover Data Characteristics on Streamflow Using the SWAT Model in the Upper Han River Basin. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 61, 102764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arregocés, H.A.; Rojano, R.; Pérez, J. Validation of the CHIRPS Dataset in a Coastal Region with Extensive Plains and Complex Topography. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 8, 100452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, A.V.; Roy, D.P.; Zhang, H.K.; Li, Z.; Yan, L.; Huang, H. Landsat 4, 5 and 7 (1982 to 2017) Analysis Ready Data (ARD) Observation Coverage over the Conterminous United States and Implications for Terrestrial Monitoring. Remote. Sens. 2019, 11, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chen, F.; Wang, B.; Harrison, M.T.; Chen, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Feng, P.; et al. Unleashing the Power of Machine Learning and Remote Sensing for Robust Seasonal Drought Monitoring: A Stacking Ensemble Approach. J. Hydrol. 2024, 634, 131102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, A.; Arsenault, K.; Kumar, S.; Shukla, S.; Peterson, P.; Wang, S.; Funk, C.; Peters-Lidard, C.D.; Verdin, J.P. A Land Data Assimilation System for Sub-Saharan Africa Food and Water Security Applications. Sci. Data 2017, 4, 170012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.C.; Getirana, A.; Policelli, F.; McNally, A.; Arsenault, K.R.; Kumar, S.; Tadesse, T.; Peters-Lidard, C.D. Upper Blue Nile Basin Water Budget from a Multi-Model Perspective. J. Hydrol. 2017, 555, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Liu, J.; Chen, D. Evaluations and Improvements of GLDAS2.0 and GLDAS2.1 Forcing Data’s Applicability for Basin Scale Hydrological Simulations in the Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 13,128–13,148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomis-Cebolla, J.; Rattayova, V.; Salazar-Galán, S.; Francés, F. Evaluation of ERA5 and ERA5-Land Reanalysis Precipitation Datasets over Spain (1951–2020). Atmos. Res. 2023, 284, 106606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Huang, W.; Smith, W.A.P.; Ren, P. A Shadow Constrained Conditional Generative Adversarial Net for SRTM Data Restoration. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 237, 111602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Pazos-de-Provens, E.; Rapp-Arrarás, Í.; Domingo-Santos, J.M. Estimating Textural Fractions of the USDA Using Those of the International System: A Quantile Approach. Geoderma 2022, 416, 115783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirachawala, C.; Shrestha, S.; Babel, M.S.; Virdis, S.G.P.; Wichakul, S. Evaluation of Global Land Use/Land Cover Products for Hydrologic Simulation in the Upper Yom River Basin, Thailand. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 708, 135148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.; Lee, S.; Du, X.; Ficklin, D.L.; Wang, Q.; Myers, D.; Singh, D.; Moglen, G.E.; McCarty, G.W.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Coupling Terrestrial and Aquatic Thermal Processes for Improving Stream Temperature Modeling at the Watershed Scale. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 126983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Meng, F.; Guo, W.; Li, X.; Fu, G. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Optimal Hydropower Reservoir Operation. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.J.; Cho, G.H.; Choi, K.S. Historical Climate Change Impacts on the Water Balance and Storage Capacity of Agricultural Reservoirs in Small Ungauged Watersheds. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2022, 41, 101114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Liu, L.; Shi, T.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Ye, R.; Lian, Z. Study of the Impact of Reservoir Water Level Decline on the Stability Treated Landslide on Reservoir Bank. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 65, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Ji, J.; Lee, S.; Yoon, J.; Yi, S.; Yi, J. Development of an Optimal Water Allocation Model for Reservoir System Operation. Water 2023, 15, 3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobadi, F.; Kang, D. Application of Machine Learning in Water Resources Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Water 2023, 15, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Her, Y.; Kang, M.S. Estimating Reservoir Inflow and Outflow From Water Level Observations Using Expert Knowledge: Dealing with an Ill-Posed Water Balance Equation in Reservoir Management. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2020WR028183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zhong, P.A.; Xu, B.; Zhu, F.; Huang, X.; Wang, H.; Ma, Y. Stochastic Programming for Floodwater Utilization of a Complex Multi-Reservoir System Considering Risk Constraints. J. Hydrol. 2021, 599, 126388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golian, S.; Yazdi, J.; Martina, M.L.V.; Sheshangosht, S. A Deterministic Framework for Selecting a Flood Forecasting and Warning System at Watershed Scale. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2015, 8, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-Level Control through Deep Reinforcement Learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo Carrera, J.M.; Udias, A. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Complex Hydropower Management: Evaluating Soft Actor-Critic with a Learned System Dynamics Model. Front. Water 2025, 7, 1649284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, F.; Razavi, S.; Elshamy, M.; Davison, B.; Sapriza-Azuri, G.; Wheater, H. Representation and Improved Parameterization of Reservoir Operation in Hydrological and Land-Surface Models. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 3735–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helseth, A.; Mo, B.; Hågenvik, H.O.; Schäffer, L.E. Hydropower Scheduling with State-Dependent Discharge Constraints: An SDDP Approach. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharme, R.E. A Global Perspective on Environmental Flow Assessment: Emerging Trends in the Development and Application of Environmental Flow Methodologies for Rivers. River Res. Appl. 2003, 19, 397–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serinaldi, F.; Kilsby, C.G.; Lombardo, F. Untenable Nonstationarity: An Assessment of the Fitness for Purpose of Trend Tests in Hydrology. Adv. Water Resour. 2018, 111, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Qiao, J.; Sun, Q.; Shen, K. A Deep Reinforcement Learning Framework for Cascade Reservoir Operations Under Runoff Uncertainty. Water 2025, 17, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, M.; Herman, J.D.; Castelletti, A.; Reed, P. Many-Objective Reservoir Policy Identification and Refinement to Reduce Policy Inertia and Myopia in Water Management. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 3355–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsel, D.R.; Hirsch, R.M.; Ryberg, K.R.; Archfield, S.A.; Gilroy, E.J. Statistical Methods in Water Resources; US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mockus, V. USDA Soil Conservation Service. National Engineering Handbook, Section 4: Hydrology, Chapter 17—Flood Routing; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, V.; Huang, Y.F.; Koo, C.H.; Ahmed, A.N.; El-Shafie, A. A Review of Reservoir Operation Optimisations: From Traditional Models to Metaheuristic Algorithms. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 3435–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Insley, M. On the Economics of Ramping Rate Restrictions at Hydro Power Plants: Balancing Profitability and Environmental Costs. Energy Econ. 2013, 39, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Xin, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Liao, Z.; Tao, T. Flooding Mitigation through Safe & Trustworthy Reinforcement Learning. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.P.; Vogel, R.M.; Lamontagne, J.R.; Mizukami, N.; Knoben, W.J.M.; Tang, G.; Gharari, S.; Freer, J.E.; Whitfield, P.H.; Shook, K.R.; et al. The Abuse of Popular Performance Metrics in Hydrologic Modeling. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR029001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accadia, C.; Casaioli, M.; Mariani, S.; Lavagnini, A.; Speranza, A.; De Venere, A.; Inghilesi, R.; Ferretti, R.; Paolucci, T.; Cesari, D.; et al. Application of a Statistical Methodology for Limited Area Model Intercomparison Using a Bootstrap Technique. Nuovo C.-Soc. Ital. Di Fis. Sez. C 2003, 26, 125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, K.; Kifer, D.; Lawson, K.; Feng, D.; Shen, C. The Data Synergy Effects of Time-Series Deep Learning Models in Hydrology. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2021WR029583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInerney, D.; Thyer, M.; Kavetski, D.; Laugesen, R.; Tuteja, N.; Kuczera, G. Multi-Temporal Hydrological Residual Error Modeling for Seamless Subseasonal Streamflow Forecasting. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR026979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, S.; Vis, M.; Seibert, J. Evaluating Model Performance: Towards a Non-Parametric Variant of the Kling-Gupta Efficiency. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2018, 63, 1941–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H. Il Development of Flood Damage Regression Models by Rainfall Identification Reflecting Landscape Features in Gangwon Province, the Republic of Korea. Land 2021, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.; Luo, Z.; Guo, Y. Reservoir Evaluation Method Based on Explainable Machine Learning with Small Samples. Unconv. Resour. 2025, 5, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wu, J.; Chu, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, G. Interpretable Machine Learning Based Quantification of the Impact of Water Quality Indicators on Groundwater Under Multiple Pollution Sources. Water 2025, 17, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Freibott, R.; García-Sánchez, Á.; Espiga-Fernández, F.; González-Santander de la Cruz, G. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Intraday Multireservoir Hydropower Management. Mathematics 2025, 13, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelletti, A.; Galelli, S.; Restelli, M.; Soncini-Sessa, R. Tree-Based Reinforcement Learning for Optimal Water Reservoir Operation. Water Resour. Res. 2010, 46, W09507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Product | Variables | Spatiotemporal Resolution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHIRPS IMERG-Final version “06” | Rainfall | 0.05° × 0.05° (daily) | Arregocés et al. [29] |

| Landsat, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9 | Bands (B2, B3, B4, B5, B6, B7) | 0.0003° × 0.0003° (daily) | Egorov et al. [30], Chen et al. [31] |

| MERRA-2 | Humidity | 0.5° × 0.5° (hourly) | McNally et al. [32], Jung et al. [33] |

| GLDAS-2.0, 2.1 | Soil moisture | 0.25° × 0.25° (daily) | Qi et al. [34] |

| ERA5-Land | Temperature, Evaporation, Solar radiation, Wind speed | 0.1° × 0.1° (daily) | Gomis-Cebolla et al. [35] |

| SRTM digital elevation data v4 | DEM | 0.0008° × 0.0008° | Dong et al. [36] |

| USDA system | Soil texture | 0.002° × 0.002° (yearly) | Corral-Pazos-de-Provens et al. [37] |

| MCD12Q1 V6.1 product | Land cover | 0.004° × 0.004° (yearly) | Chirachawala et al. 2020 [38] |

| Flood Risk Value | Meaning |

|---|---|

| <0 | Storage is below flood threshold → No flood risk |

| =0 | Storage is exactly at the threshold → Flood-safe limit reached |

| 0 < value ≤ 1 | Storage is within flood control zone → Potential flood risk |

| >1 | Storage exceeds total flood buffer → High flood risk (overflow) |

| Metric | PPO | DQN | DDPG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative Reward | 8691 | 8679 | 8235 |

| Action Stability | 0.0059 | 0.1737 | 0.0792 |

| Total Capacity Violations | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Flood Control Violations | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| Model | Flood_Weight | Deviation_Weight | Cumulative Reward | Action Stability (Std) | Flood Violations | Capacity Violations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDPG | 0.7 | 0.3 | 9323 | 0.073 | 2 | 0 |

| PPO | 0.7 | 0.3 | 9597 | 0.041 | 6 | 0 |

| DQN | 0.7 | 0.3 | 9591 | 0.167 | 0 | 0 |

| DDPG | 0.5 | 0.5 | 8234 | 0.073 | 2 | 0 |

| PPO | 0.5 | 0.5 | 8691 | 0.041 | 6 | 0 |

| DQN | 0.5 | 0.5 | 8680 | 0.167 | 0 | 0 |

| DDPG | 0.3 | 0.7 | 7145 | 0.073 | 2 | 0 |

| PPO | 0.3 | 0.7 | 7784 | 0.041 | 6 | 0 |

| DQN | 0.3 | 0.7 | 7769 | 0.167 | 0 | 0 |

| Date | Metric | Actual | DDPG | PPO | DQN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995-08-25 | Storage (million m3) | 2602 | 2066 | 2152 | 1784 |

| Discharge (m3/s) | 2226 | 1139 | 1022 | 1069 | |

| FR (–) | 0.429 | −0.187 | 0.000 | −0.353 | |

| 1999-08-01 | Storage (million m3) | 1504 | 1065 | 1154 | 977 |

| Discharge (m3/s) | 51 | 142 | 23 | 0 | |

| FR (–) | −0.743 | −1.167 | −1.037 | −1.234 | |

| 1999-08-02 | Storage (million m3) | 1893 | 1365 | 1410 | 1170 |

| Discharge (m3/s) | 169 | 139 | 79 | 0 | |

| FR (–) | −0.397 | −0.882 | −0.795 | −1.022 | |

| 2006-07-15 | Storage (million m3) | 1786 | 1167 | 1378 | 1138 |

| Discharge (m3/s) | 233 | 0 | 128 | 0 | |

| FR (–) | −0.536 | −1.092 | −0.895 | −1.129 |

| Model | RMSE (m3/s) | RMSE 95% CI (Low–High) | MAE (m3/s) | MAE 95% CI (Low–High) | NSE | NSE 95% CI (Low–High) | KGE | KGE 95% CI (Low–High) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDPG | 49.36 | 40.55–59.27 | 19.09 | 18.27–19.96 | 0.67 | 0.54–0.74 | 0.60 | 0.56–0.63 |

| PPO | 51.08 | 41.83–61.07 | 19.71 | 18.89–20.61 | 0.65 | 0.52–0.72 | 0.56 | 0.51–0.59 |

| DQN | 50.11 | 40.71–60.35 | 19.51 | 18.68–20.42 | 0.66 | 0.53–0.73 | 0.57 | 0.52–0.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sseguya, F.; Jun, K.S. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Optimized Reservoir Operation and Flood Risk Mitigation. Water 2025, 17, 3226. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223226

Sseguya F, Jun KS. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Optimized Reservoir Operation and Flood Risk Mitigation. Water. 2025; 17(22):3226. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223226

Chicago/Turabian StyleSseguya, Fred, and Kyung Soo Jun. 2025. "Deep Reinforcement Learning for Optimized Reservoir Operation and Flood Risk Mitigation" Water 17, no. 22: 3226. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223226

APA StyleSseguya, F., & Jun, K. S. (2025). Deep Reinforcement Learning for Optimized Reservoir Operation and Flood Risk Mitigation. Water, 17(22), 3226. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223226