Spatiotemporal Patterns, Characteristics, and Ecological Risk of Microplastics in the Surface Waters of Shijiu Lake (Nanjing, China)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

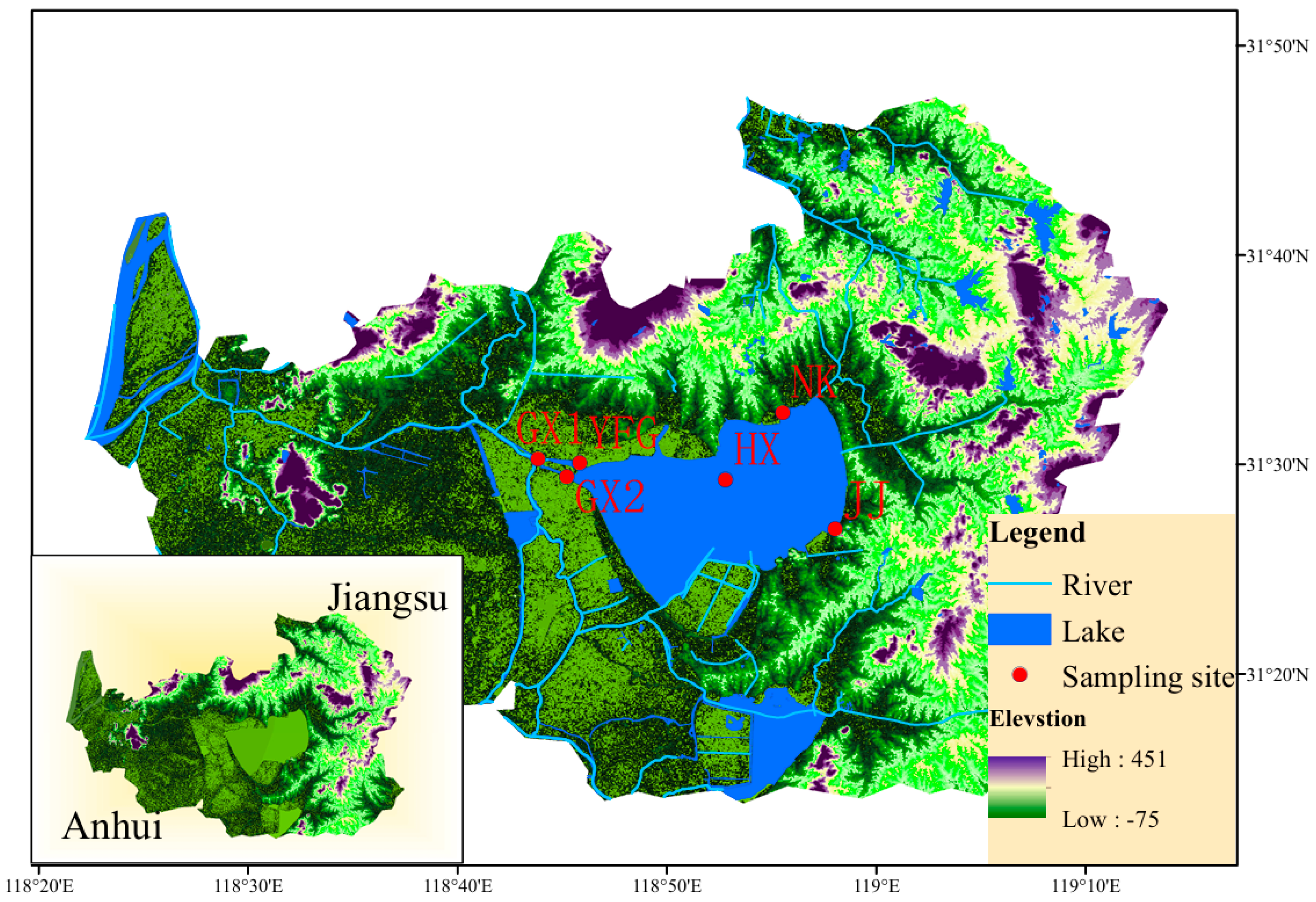

2.1. Study Area and Sampling Period

2.2. Water Sample Collection Method

2.3. MPs Pretreatment and Detection

2.4. MPs Counting and Identification

2.5. Quality Control

2.6. MP Risk Assessment Methods

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

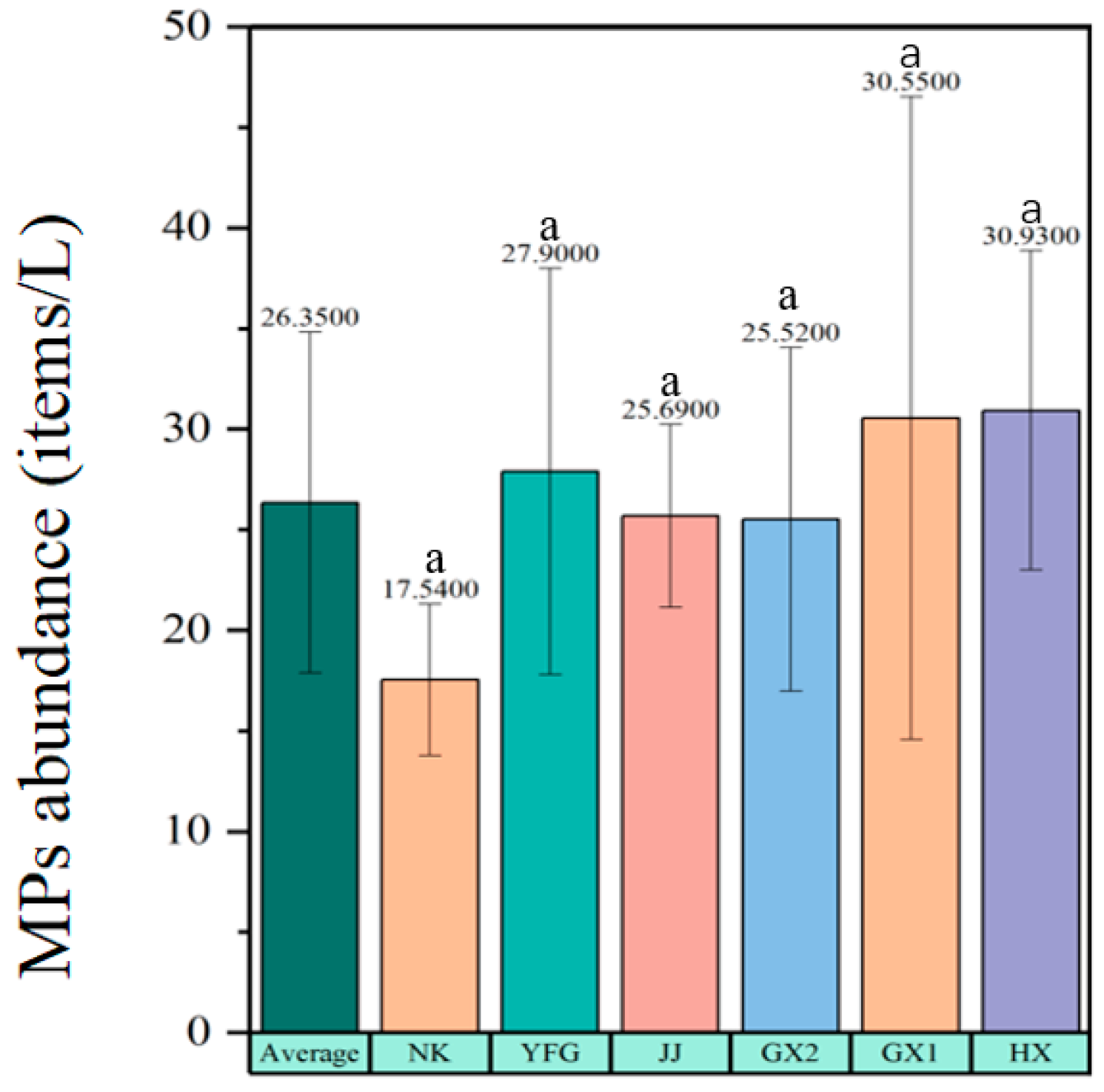

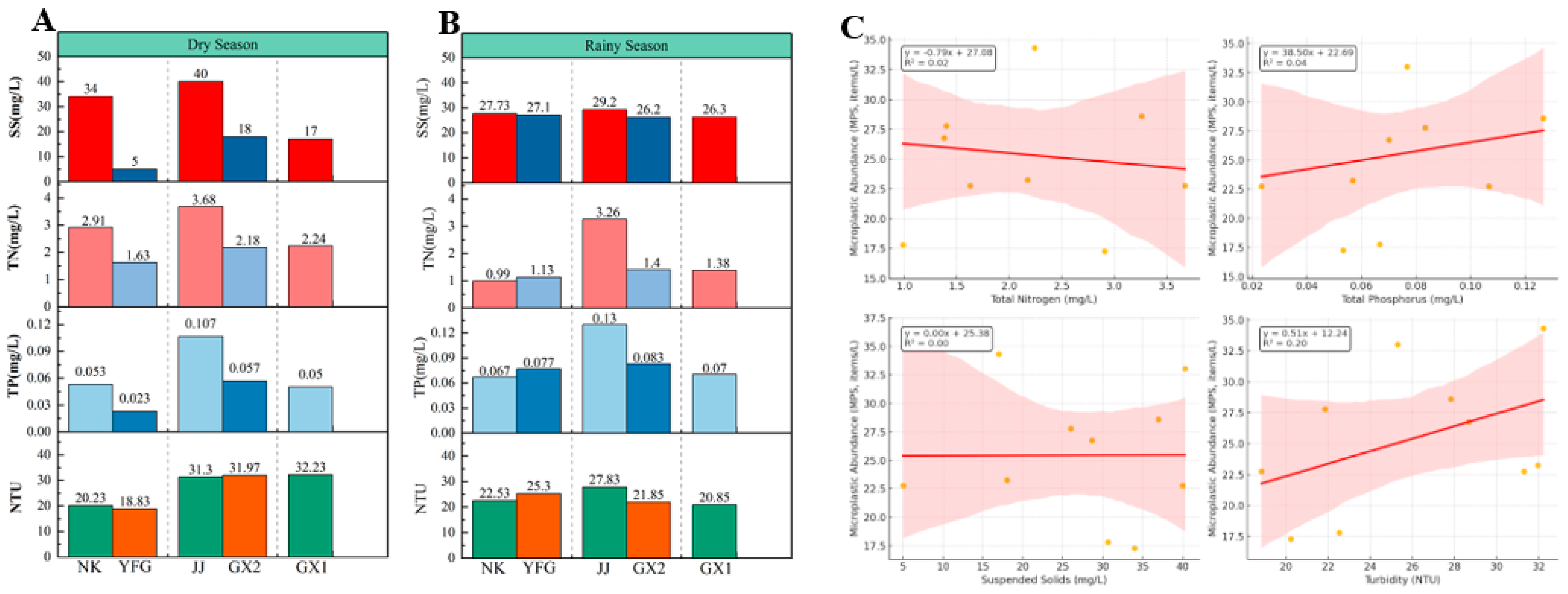

3.1. Spatial Distribution of MP Abundance

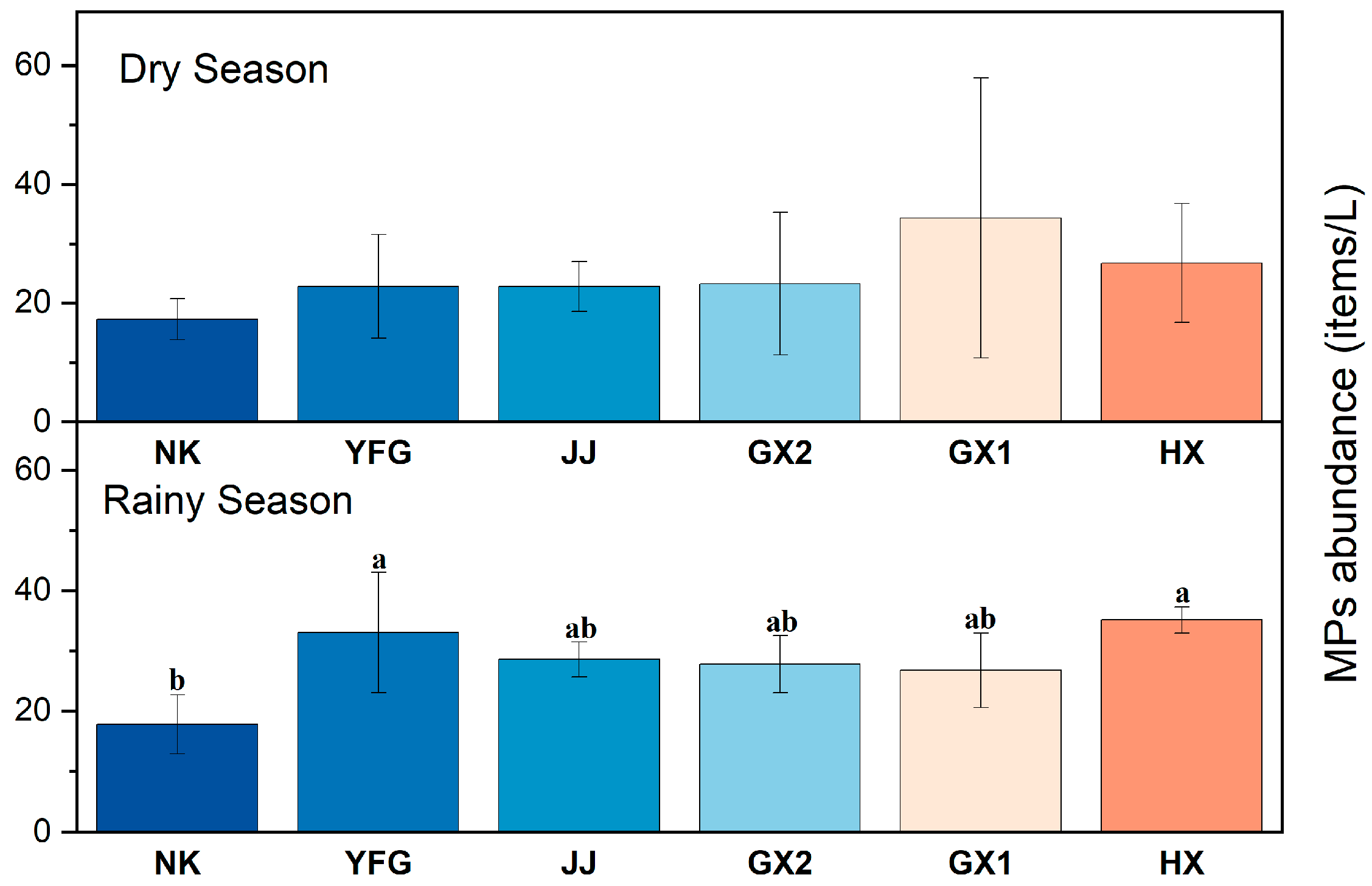

3.2. Seasonal Variation Trends in MP Abundance

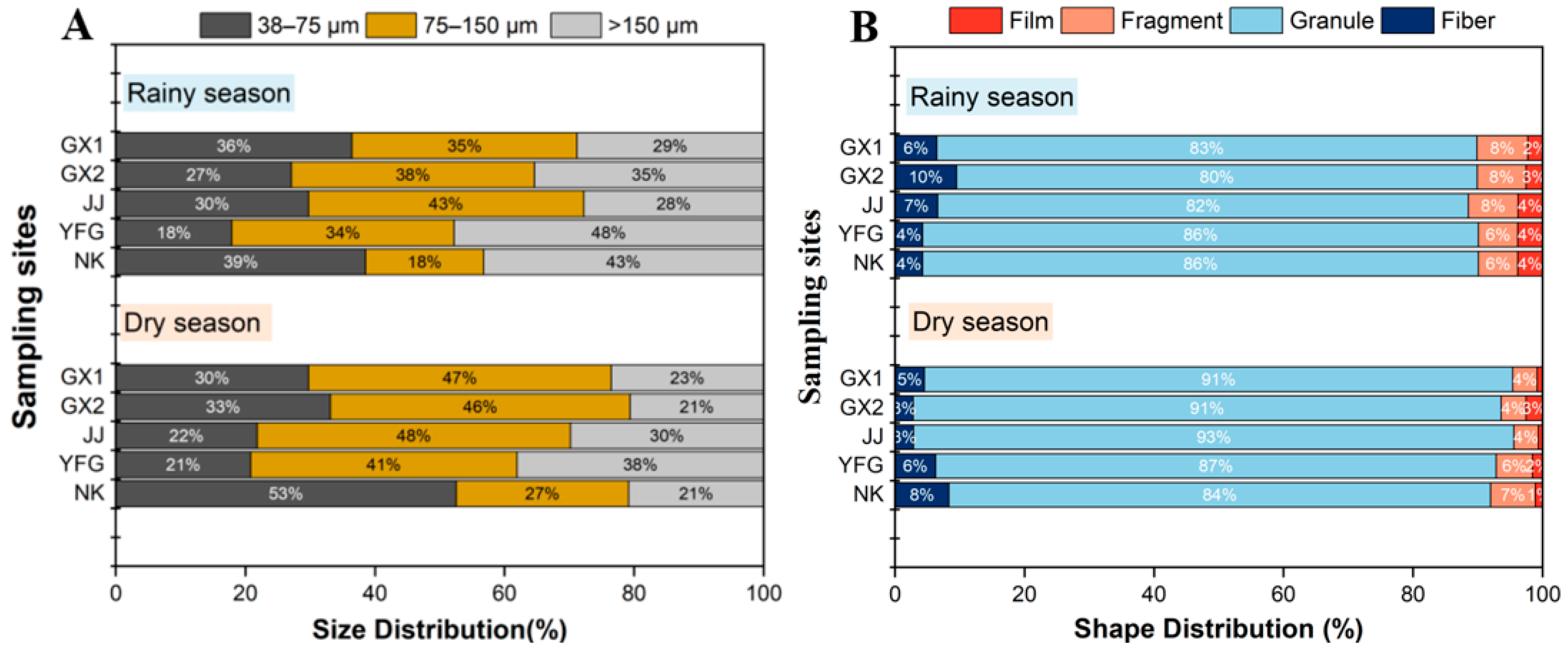

3.3. MP Size Distribution and Morphological Characteristics

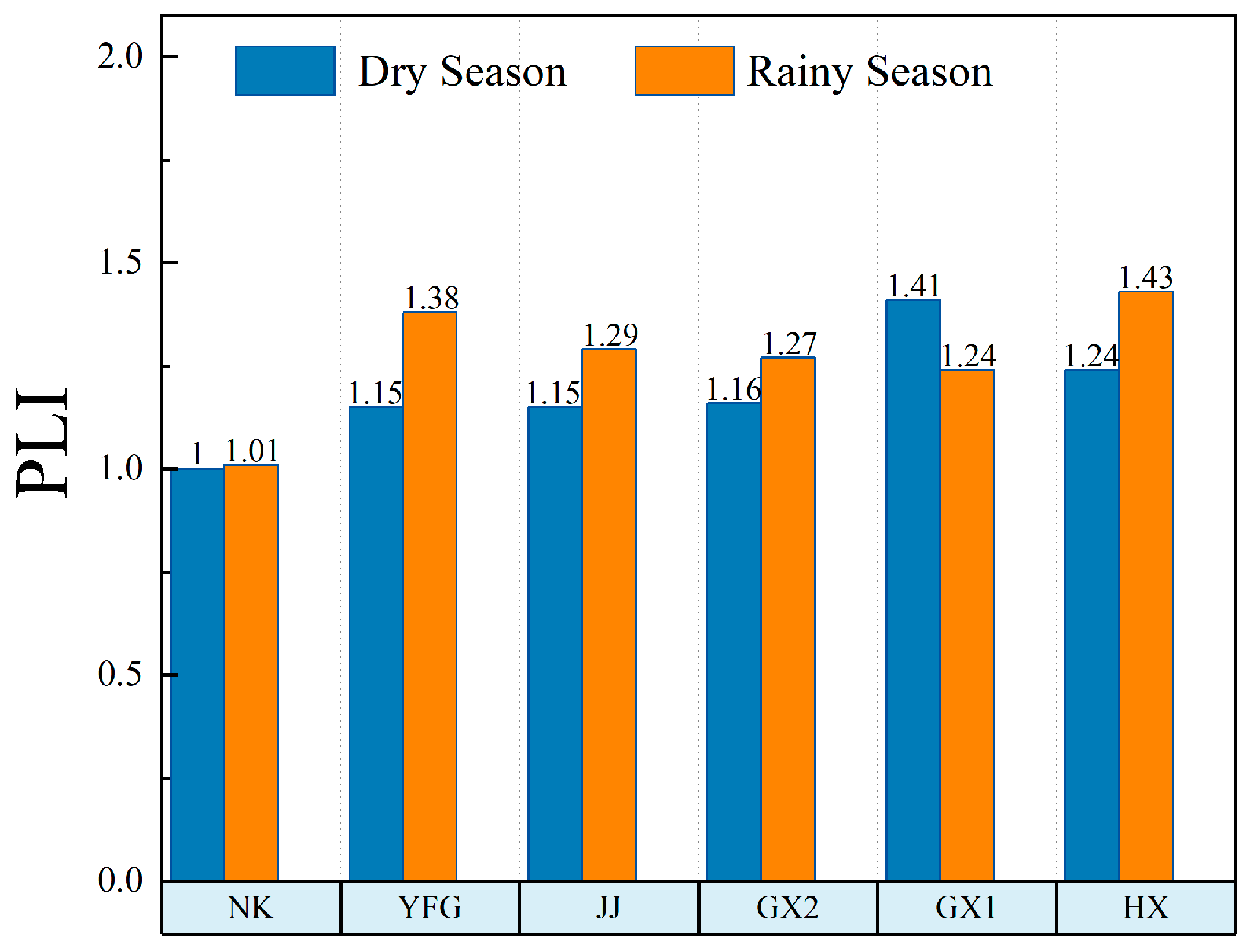

3.4. Hazard Screening with the Pollution Load Index (PLI)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bergmann, M.; Collard, F.; Fabres, J.; Gabrielsen, G.W.; Provencher, J.F.; Rochman, C.M.; van Sebille, E.; Tekman, M.B. Plastic pollution in the Arctic. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Bai, H.; Chen, B.; Sun, X.; Qu, K.; Xia, B. Microplastic pollution in North Yellow Sea, China: Observations on occurrence, distribution and identification. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.; Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R.P.; Davis, A.; Rowland, S.J.; John, A.W.G.; McGonigle, D.; Russell, A.E. Lost at Sea: Where Is All the Plastic? Science 2004, 304, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Machado, A.A.; Kloas, W.; Zarfl, C.; Hempel, S.; Rillig, M.C. Microplastics as an emerging threat to terrestrial ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Sun, F.; Liao, H.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, F. Quantitative characteristics and multiple probabilistic risk assessment of small-sized microplastics in the middle and lower reaches of the Hanjiang River, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 220, 118404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, Q.Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zuo, C.C.; Shi, H.H. An Overview of Chemical Additives on (Micro)Plastic Fibers: Occurrence, Release, and Health Risks. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2022, 260, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Noori, R.; Abolfathi, S. Microplastics in freshwater systems: Dynamic behaviour and transport processes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 205, 107578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, O.S.; Farner Budarz, J.; Hernandez, L.M.; Tufenkji, N. Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Aquatic Environments: Aggregation, Deposition, and Enhanced Contaminant Transport. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1704–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Sun, P.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Ren, H.; Wu, B. Changes in characteristics and risk of freshwater microplastics under global warming. Water Res. 2024, 260, 121960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava, V.; Chandra, S.; Aherne, J.; Alfonso, M.B.; Antão-Geraldes, A.M.; Attermeyer, K.; Bao, R.; Bartrons, M.; Berger, S.A.; Biernaczyk, M.; et al. Plastic debris in lakes and reservoirs. Nature 2023, 619, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zou, L.; Zhao, G. Microplastic abundance, distribution, and composition in the surface water and sediments of the Yangtze River along Chongqing City, China. J. Soils Sediments 2021, 21, 1840–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zheng, K.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, G.; Peng, X. Distribution, sedimentary record, and persistence of microplastics in the Pearl River catchment, China. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 251, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Niu, X.; Tang, M.; Zhang, B.-T.; Wang, G.; Yue, W.; Kong, X.; Zhu, J. Distribution of microplastics in surface water of the lower Yellow River near estuary. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 135601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, T.; Liu, L.; Fan, Y.; Rao, W.; Zheng, J.; Qian, X. Distribution and sedimentation of microplastics in Taihu Lake. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 148745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Chen, X.; Zha, S.; Chen, X.; Yu, Y.; Duan, X.; Cao, Y.; Liang, Y. Distribution and Characteristics of Microplastics in Agricultural Soils around Gehu Lake, China. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zheng, J.; Deng, L.; Rao, W.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, T.; Qian, X. Spatiotemporal dynamics of microplastics in an urban river network area. Water Res. 2022, 212, 118116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Liao, C.-M.; Chen, S.-C. Toxic metal-adsorbed microplastics threaten human digestive system: A bioaccessibility-based risk assessment. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 383, 126900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freilinger, J.; Kappacher, C.; Huter, K.; Hofer, T.S.; Back, J.O.; Huck, C.W.; Bakry, R. Interactions between perfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) and microplastics (MPs): Findings from an extensive investigation. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 18, 100740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, H.J.H. Oxidation of tartaric acid in presence of iron. J. Chem. Soc. Trans. 1894, 65, 899–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grbic, J.; Nguyen, B.; Guo, E.; You, J.B.; Sinton, D.; Rochman, C.M. Magnetic Extraction of Microplastics from Environmental Samples. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2019, 6, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Paul Chen, J. Microplastics in freshwater systems: A review on occurrence, environmental effects, and methods for microplastics detection. Water Res. 2018, 137, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, A.; Garrido-Amador, P.; Martínez, I.; Samper, M.D.; López-Martínez, J.; Gómez, M.; Packard, T.T. Novel methodology to isolate microplastics from vegetal-rich samples. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 129, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reineccius, J.; Bresien, J.; Waniek, J.J. Separation of microplastics from mass-limited samples by an effective adsorption technique. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 788, 147881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, D.L.; Wilson, J.G.; Harris, C.; Jeffrey, D. Problems in the assessment of heavy-metal levels in estuaries and the formation of a pollution index. Helgoländer Meeresunters 1980, 33, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakib, M.R.J.; Al Nahian, S.; Madadi, R.; Haider, S.M.B.; De-la-Torre, G.E.; Walker, T.R.; Jonathan, M.P.; Cowger, W.; Khandaker, M.U.; Idris, A.M. Spatiotemporal trends and characteristics of microplastic contamination in a large river-dominated estuary. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2023, 25, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jian, M.; Zhou, L.; Li, W. Distribution and characteristics of microplastics in the sediments of Poyang Lake, China. Water Sci. Technol. 2019, 79, 1868–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Yin, L.; Wen, X.; Du, C.; Wu, L.; Long, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yin, Q.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Microplastics in Sediment and Surface Water of West Dongting Lake and South Dongting Lake: Abundance, Source and Composition. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, C.; Ju, L.; Ping, W.; Rui, W.; Zhiwei, Y.; Yuanyuan, Y.; Chunnuan, D. Pollution Status and Characterization of Microplastics in Some Lakes and Reservoirs in China. Wetl. Sci. 2024, 22, 536544. [Google Scholar]

- Grbić, J.; Helm, P.; Athey, S.; Rochman, C.M. Microplastics entering northwestern Lake Ontario are diverse and linked to urban sources. Water Res. 2020, 174, 115623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Lei, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W. Microplastic pollution in sophisticated urban river systems: Combined influence of land-use types and physicochemical characteristics. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.X.; Wang, W.L.; Yu, X.G.; Lin, Z.Y.; Chen, J. Heterogeneity and Contribution of Microplastics From Industrial and Domestic Sources in a Wastewater Treatment Plant in Xiamen, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 770634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Li, Q.; Xia, X.; Zhang, H. The effects of land use types on microplastics in river water: A case study on the mainstream of the Wei River, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, K.R.; Lu, H.-C.; Sharley, D.J.; Pettigrove, V. Associations between microplastic pollution and land use in urban wetland sediments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 22551–22561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Tian, X.; Zhao, R.; Wang, B.; Qi, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Shan, B. Spatiotemporal and vertical distribution characteristics and ecological risks of microplastics in typical shallow lakes in northern China. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 382, 126773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boctor, J.; Hoyle, F.C.; Farag, M.A.; Ebaid, M.; Walsh, T.; Whiteley, A.S.; Murphy, D.V. Microplastics and nanoplastics: Fate, transport, and governance from agricultural soil to food webs and humans. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, R.; Woodward, J.; Rothwell, J.J. Microplastic contamination of river beds significantly reduced by catchment-wide flooding. Nat. Geosci. 2018, 11, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Chen, C.C.; Zhu, X.; Pan, K.; Xu, X. Risk of aquaculture-derived microplastics in aquaculture areas: An overlooked issue or a non-issue? Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 923471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.M.; Ren, Q.Q.; Liu, C.L.; Xian, W.W. Seasonal and Spatial Variations in Fish Assemblage in the Yangtze Estuary and Adjacent Waters and Their Relationship with Environmental Factors. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Cavalcanti, J.S.; Silva, J.C.P.; de Andrade, F.M.; Brito, A.M.S.S.; da Costa, M.F. Microplastic pollution in sediments of tropical shallow lakes. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 855, 158671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.H.; Li, J.Z.; Zhou, K.K.; Feng, P.; Dong, L.X. The effects of surface pollution on urban river water quality under rainfall events in Wuqing district, Tianjin, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchcock, J.N. Storm events as key moments of microplastic contamination in aquatic ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 734, 139436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.C.; Wang, H.; Liang, D.F.; Yuan, W.H.; Xu, H.S.; Li, S.Q.; Li, J.L. Disentangling the retention preferences of estuarine suspended particulate matter for diverse microplastic types. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 366, 125390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Ye, W.; Xiang, S.; Fan, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W. Factors influencing the migration and distribution of microplastics in the environment. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2025, 19, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.J.; Wang, Y.L.; Adnan, M.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.Q. Natural Factors of Microplastics Distribution and Migration in Water: A Review. Water 2024, 16, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.F.; Yue, Q.; Chen, G.L.; Wang, J. Microplastics in rainwater/stormwater environments: Influencing factors, sources, transport, fate, and removal techniques. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 165, 117147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, C.; Lara, L.Z.; Fernandes, A.N. Revealing microplastic dynamics: The impact of precipitation and depth in urban river ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 111231–111243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ye, Q.; Sun, L.; Liu, J.; Huang, M.; Wang, T.; Wu, P.; Zhu, N. Impact of persistent rain on microplastics distribution and plastisphere community: A field study in the Pearl River, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 879, 163066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.A.; Crump, P.; Niven, S.J.; Teuten, E.; Tonkin, A.; Galloway, T.; Thompson, R. Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Woldwide: Sources and Sinks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 9175–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priya, K.L.; Renjith, K.R.; Joseph, C.J.; Indu, M.S.; Srinivas, R.; Haddout, S. Fate, transport and degradation pathway of microplastics in aquatic environment-A critical review. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2022, 56, 102647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Redondo-Hasselerharm, P.E.; Nor, N.H.M.; de Ruijter, V.N.; Mintenig, S.M.; Kooi, M. Risk assessment of microplastic particles. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamas, A.; Moon, H.; Zheng, J.J.; Qiu, Y.; Tabassum, T.; Jang, J.H.; Abu-Omar, M.; Scott, S.L.; Suh, S. Degradation Rates of Plastics in the Environment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 8, 3494–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.C.; Tse, H.F.; Fok, L. Plastic waste in the marine environment: A review of sources, occurrence and effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 566, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, M.; Francalanci, S.; Serra, T.; Colomer, J.; Solari, L. Settling velocities of microplastics with different shapes in sediment-water mixtures. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 372, 126071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ji, J.; Huang, J.; Chen, M.; Jin, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Qian, X.; Ma, H.; Xu, J. Spatiotemporal Patterns, Characteristics, and Ecological Risk of Microplastics in the Surface Waters of Shijiu Lake (Nanjing, China). Water 2025, 17, 3224. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223224

Ji J, Huang J, Chen M, Jin H, Wang X, Wu Y, Qian X, Ma H, Xu J. Spatiotemporal Patterns, Characteristics, and Ecological Risk of Microplastics in the Surface Waters of Shijiu Lake (Nanjing, China). Water. 2025; 17(22):3224. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223224

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Jie, Juan Huang, Ming Chen, Hui Jin, Xinyue Wang, Yufeng Wu, Xiuwen Qian, Haoqin Ma, and Jin Xu. 2025. "Spatiotemporal Patterns, Characteristics, and Ecological Risk of Microplastics in the Surface Waters of Shijiu Lake (Nanjing, China)" Water 17, no. 22: 3224. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223224

APA StyleJi, J., Huang, J., Chen, M., Jin, H., Wang, X., Wu, Y., Qian, X., Ma, H., & Xu, J. (2025). Spatiotemporal Patterns, Characteristics, and Ecological Risk of Microplastics in the Surface Waters of Shijiu Lake (Nanjing, China). Water, 17(22), 3224. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223224