Fe-Doped g-C3N4 for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Brilliant Blue Dye

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Fe/g-C3N4

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Experimental Procedures

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterizations of Fe/g-C3N4

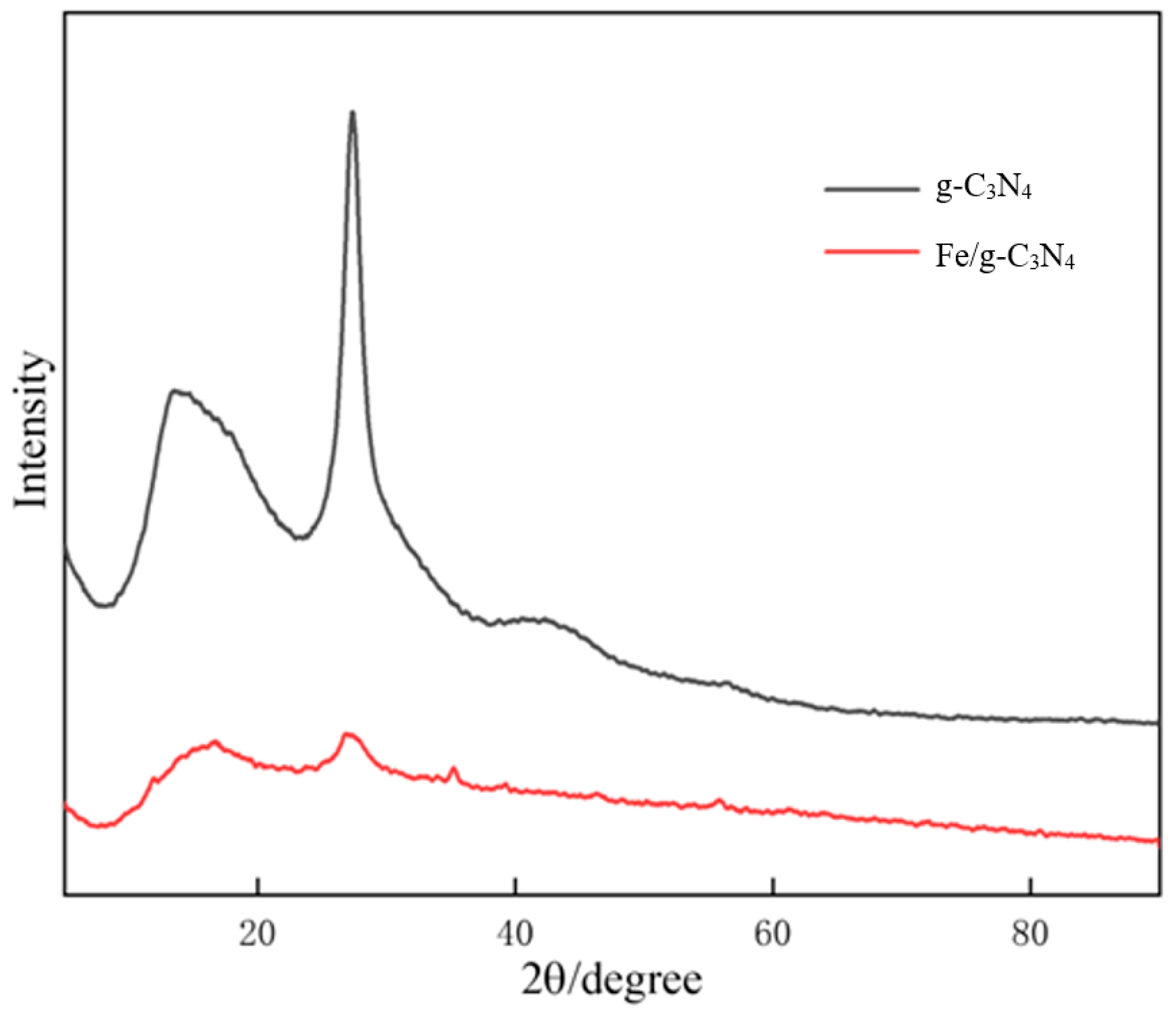

3.1.1. Crystal Structure Analysis

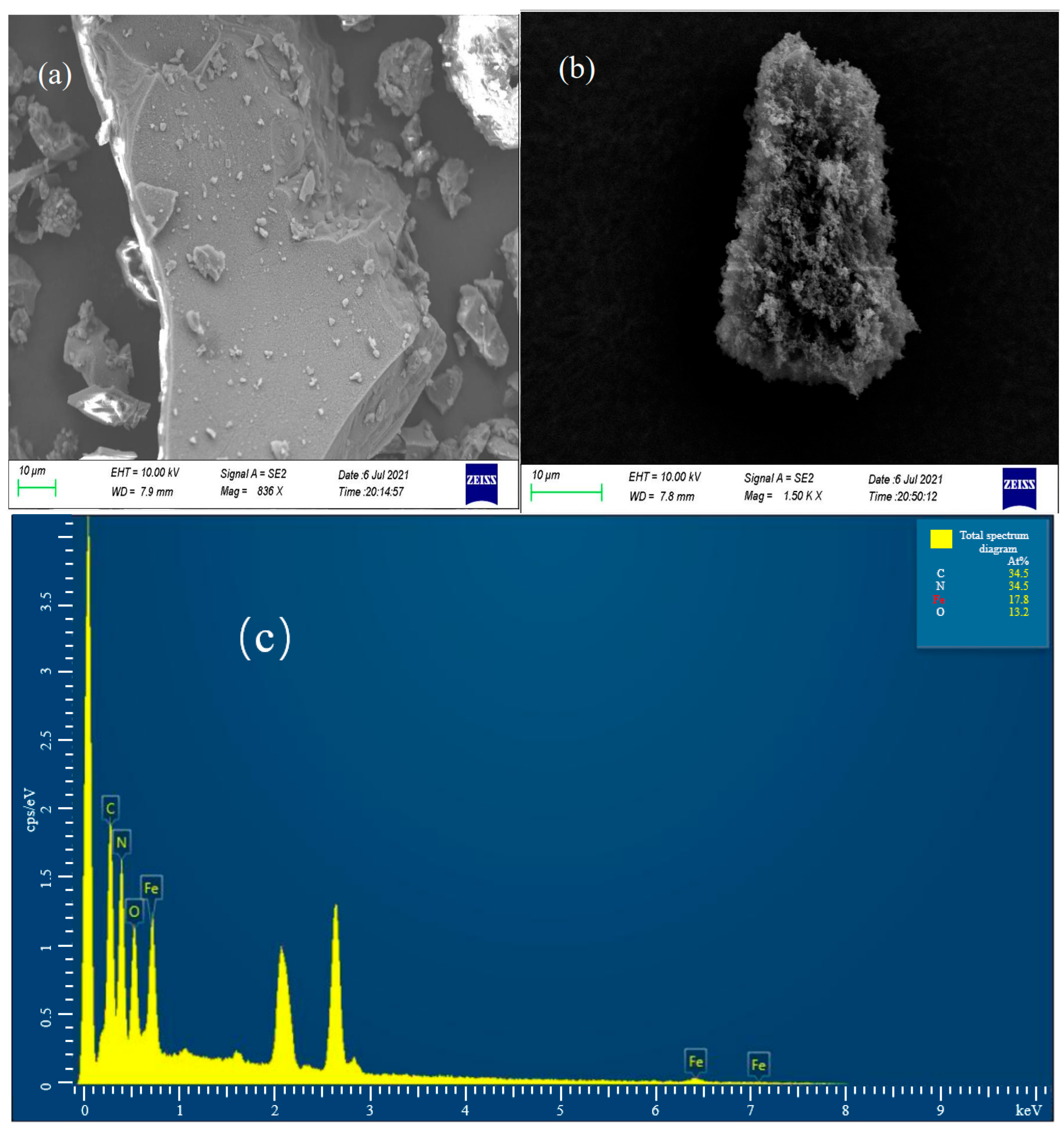

3.1.2. Microtopography Analysis

3.1.3. Chemical State

3.1.4. Specific Surface Area

3.1.5. UV–Visible Light Analysis of Solids

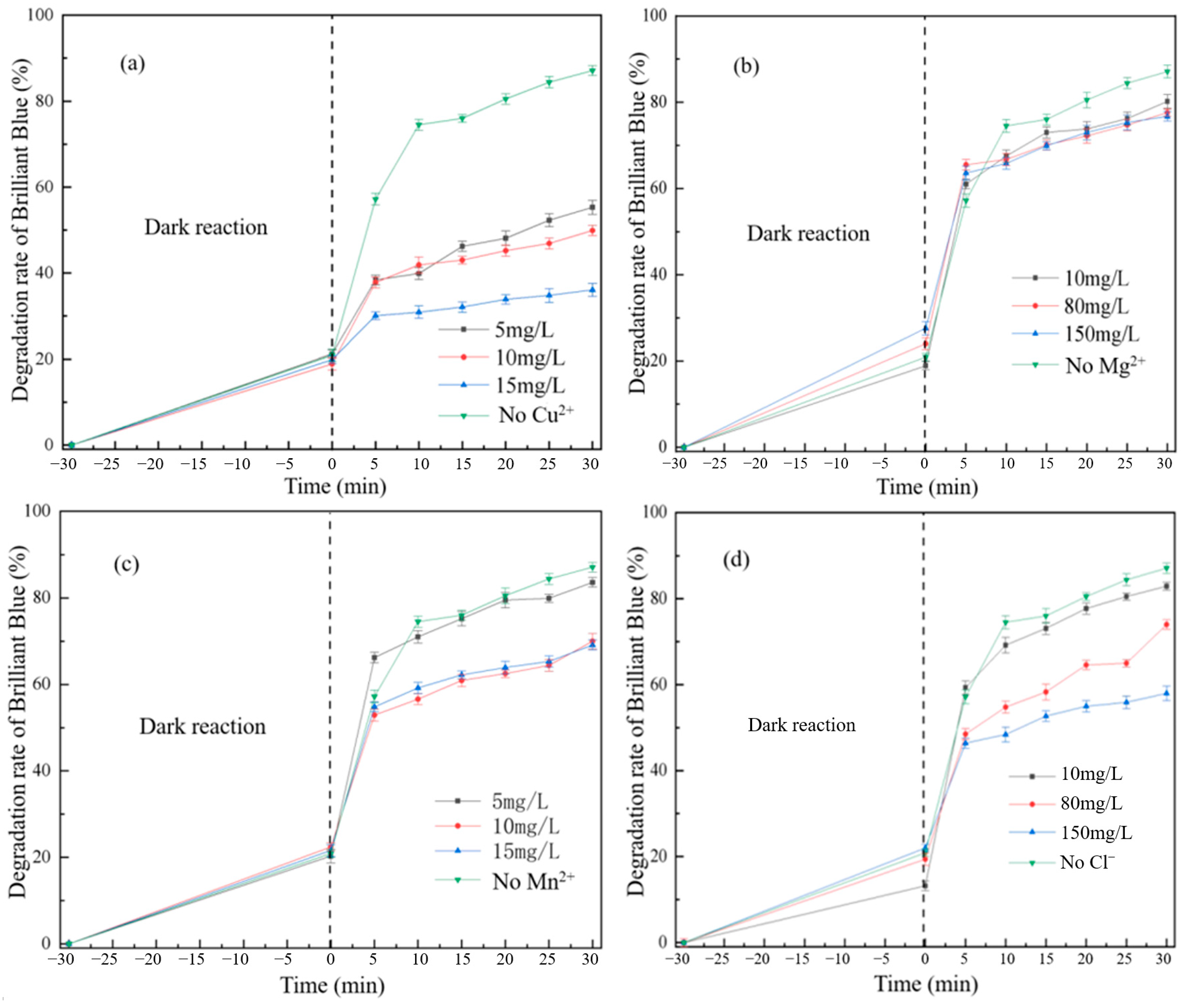

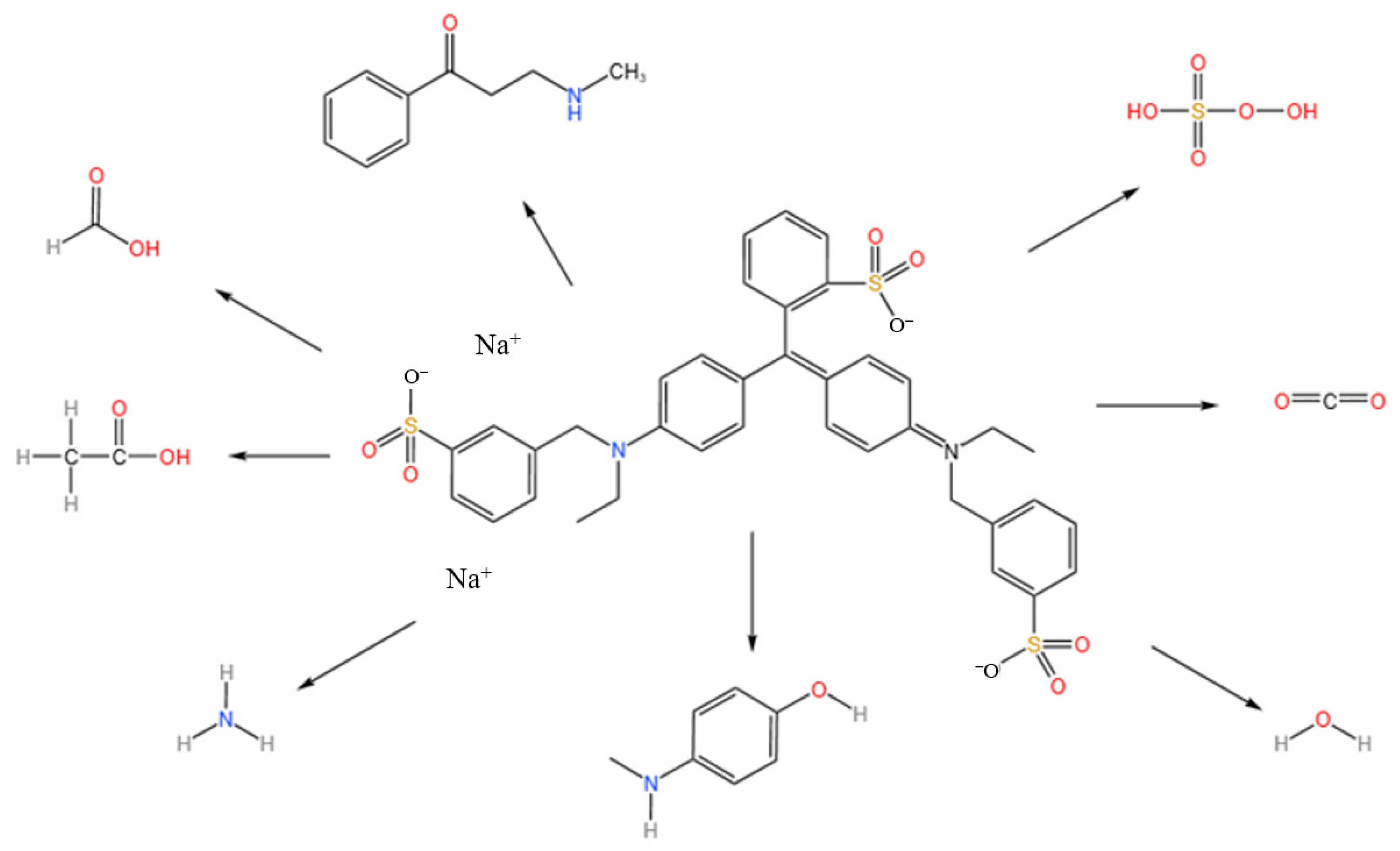

3.2. Analysis of the Influence of Multiple Factors on the Degradation of Brilliant Blue

3.2.1. Effect of Synthetic Reaction Factors on Degradation of Brilliant Blue

3.2.2. Interaction Analysis of Factors

3.3. Catalytic Performance of Different Degradation Processes

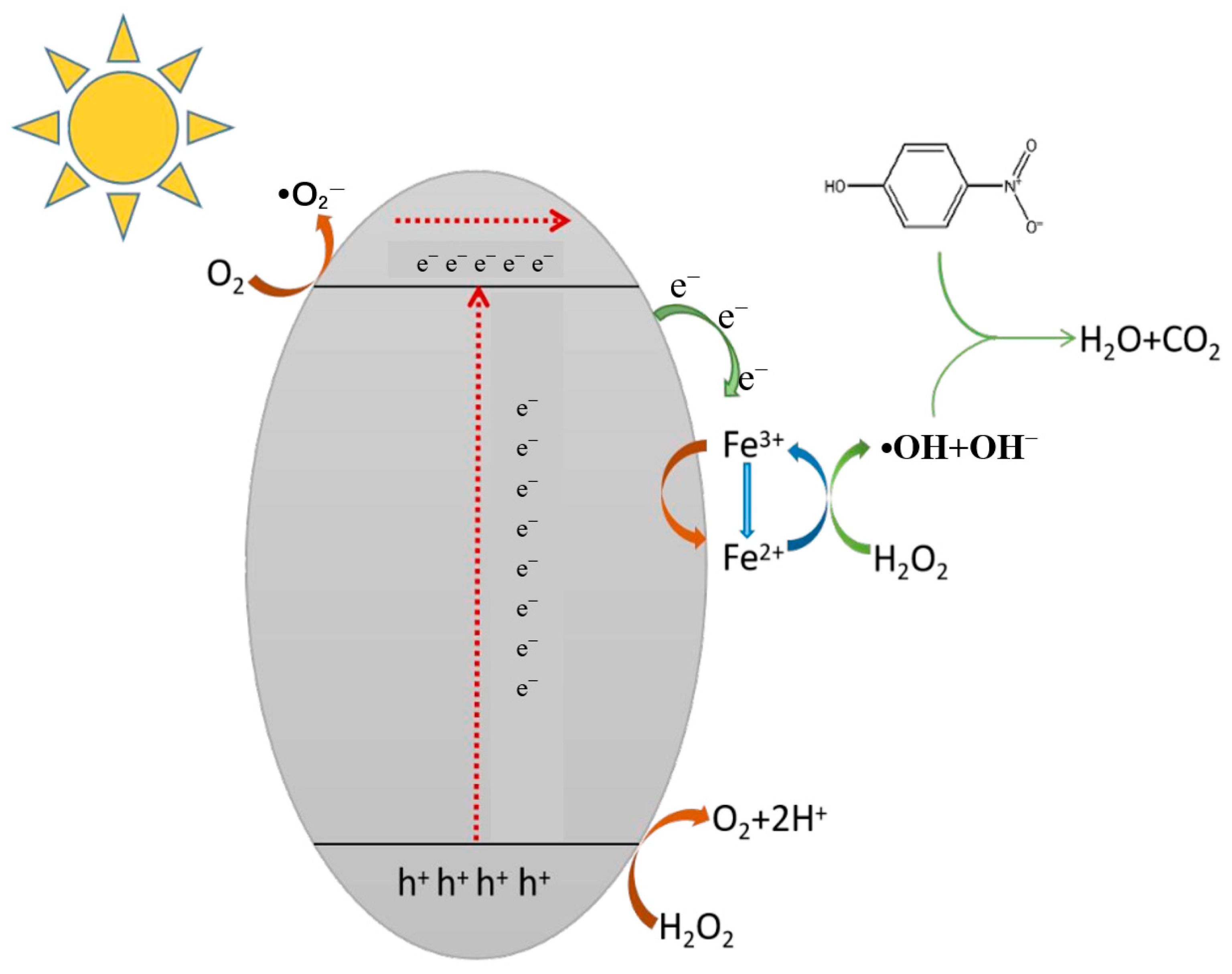

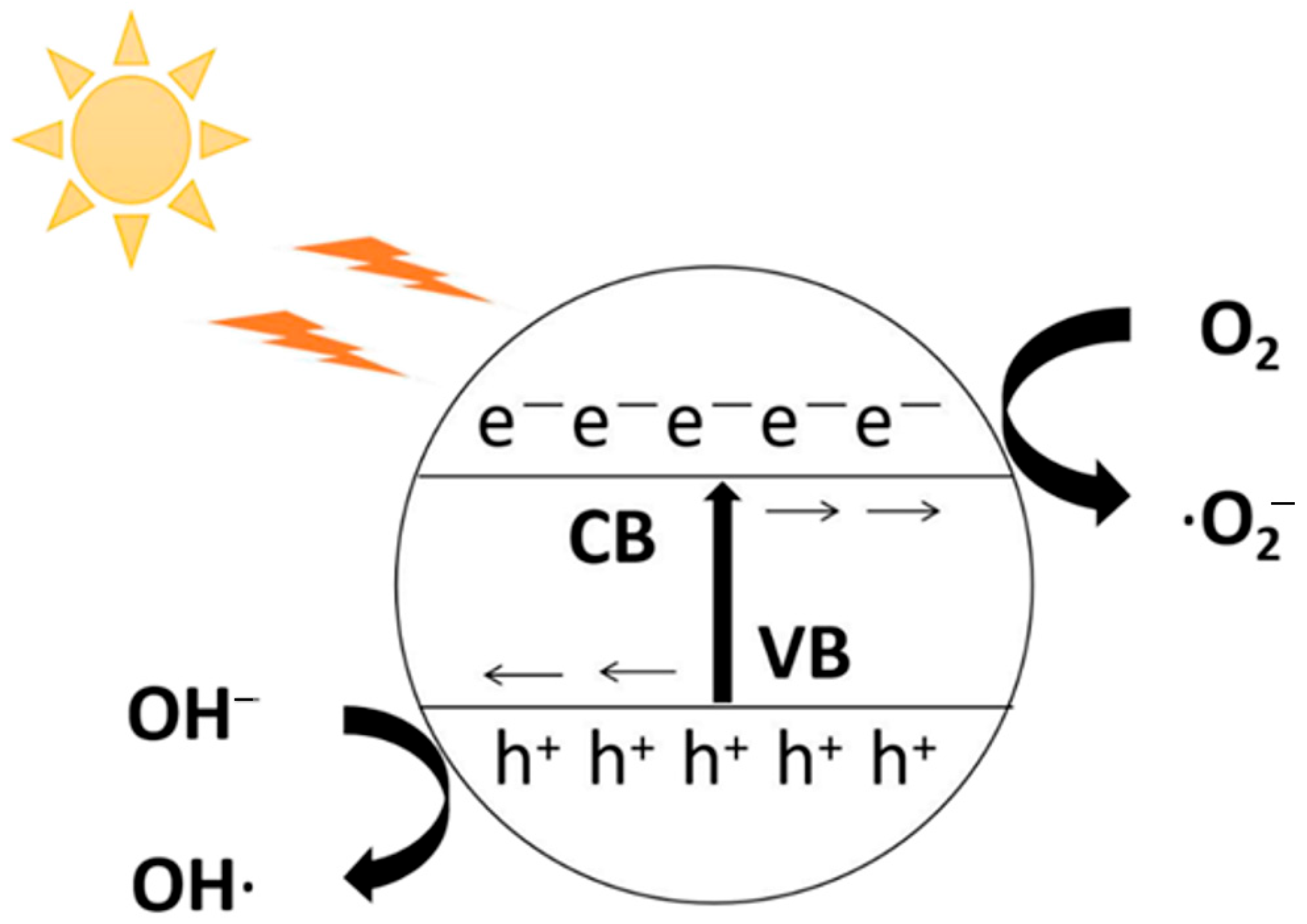

3.4. Photocatalytic Degradation Mechanism of Brilliant Blue

3.4.1. Optical Property Analysis

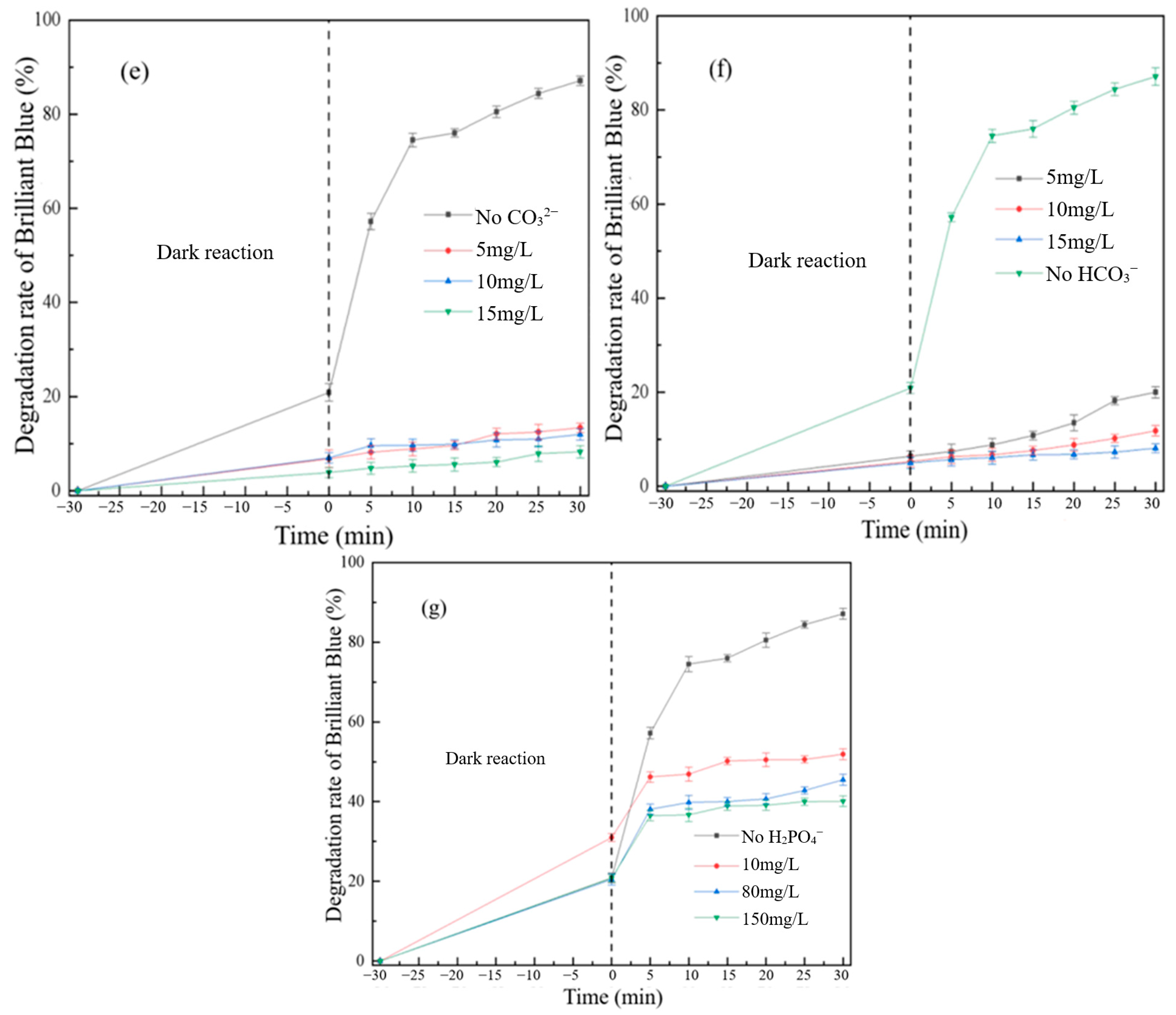

3.4.2. Analysis of Photocatalytic Degradation Pathway of Brilliant Blue

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oliveros, E.; Legrini, O.; Hohl, M.; Müller, T.; Braun, A.M. Industrial waste water treatment: Large scale development of a light-enhanced Fenton reaction. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 1997, 36, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Kuate, L.J.N.; Zhang, H.; Hou, J.; Wen, H.; Lu, C.; Li, C.; Shi, W. Photothermally enabled black g-C3N4 hydrogel with integrated solar-driven evaporation and photo-degradation for efficient water purification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 355, 129751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alveztovar, B.; Scalize, P.S.; Albuquerque, A.; Angiolillorodríguez, G.; Ebang, M.N.; Oliveira, T.F. Agro-Industrial Waste Upcycling into Activated Carbons: A Sustainable Approach for Dye Removal and Wastewater Treatment. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Lu, M.; Wei, P.; Xie, Y.; Xie, H.; Liu, M.; Li, L.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Qi, Y. Photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants in sewage using CeO2/ZnO 3D nanoflowers. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.R.; Liu, X.Y.; Ji, L.L.; Lou, Z.X.; Yuan, X. The emission reduction effect of industrial wastewater in the pilot city policy of water ecological civilization. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zcan, E.; Altun, A.; Zorlu, Y. Highly Effective Photocatalytic Removal of Astrazon Blue, Allura Red, and Brilliant Blue Dyes from Aqueous Media Using a Stable Zr(IV)-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e202404363. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Liu, H.; Deng, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Yang, G. Interference enhanced SPR-mediated visible-light responsive photocatalysis of periodically ordered ZnO nanorod arrays decorated with Au nanoparticles. Micro Nanostruct. 2025, 197, 208025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagakawa, H. Introduction and Quantification of Sulfide Ion Defects in Highly Crystalline CdS for Photocatalysis Applications. Phys. Status Solidi A Appl. Mater. Sci. 2024, 221, 2400213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Yu, Q.; Xue, H.; Zhang, W.; Ren, H.; Geng, J. Photochemical behavior of extracellular polymeric substances in intimately coupled TiO2 photocatalysis and biodegradation system. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 416, 131752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, J.; Yuan, Z.; Chang, Q.; Guo, C.; Yan, M. Dodecahedral Ag3PO4 photocatalysis and biodegradation synergistically remove phenol and generate electricity. Renew. Energy 2024, 231, 120994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Ou, Y.; Tu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, C.; Xiang, X.; Bao, M. Preparation and performance of g-C3N4/g-C3N5 homojunction photocatalyst activated peroxymonosulfate for ceftriaxone sodium degradation. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 148, 111402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Qin, L.; Pan, Y. Efficient charge carrier separation over carbon-rich graphitic carbon nitride for remarkably improved photocatalytic performance in emerging organic micropollutant degradation and H2 production. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 329, 125230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Q.; Wang, H.; Kuang, J.; Liu, B.; Zheng, S.; Zhao, Q.; Jia, W.; Wu, Y.; Lu, H.; Wu, Q.; et al. Light and nitrogen vacancy-intensified nonradical oxidation of organic contaminant with Mn (III) doped carbon nitride in peroxymonosulfate activation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 454, 131463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.K.; Tarul Bais, A.P.S.; Rosy. Electrodeposited Phosphorous-Doped Graphitic Carbon Nitride as A Versatile Metal Free Interface for Tryptophan Detection in Dietary, Nutritional, and Clinical Samples. Microchem. J. 2024, 203, 110833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Jiang, L.; Yu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Yuan, X.; Liang, J.; Li, H.; Wu, Z. Defective polymeric carbon nitride: Fabrications, photocatalytic applications and perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 130991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuna, Ö.; Mert, H.H.; Mert, M.S.; Simsek, E.B. Tubular graphitic carbon nitride-anchored on porous diatomite for enhanced solar energy efficiency in photocatalytic remediation and energy storage performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Yao, Y.; Fujii, T.; Iseri, Y.; Zhu, X. Establishing g-C3N4-Vn/FeIn2S4 heterostructure for in-situ H2O2 generation and activation to degrade tetracycline in photo-Fenton process under visible light. Environ. Res. 2025, 277, 121656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Hu, X.; Tian, T.; Cai, B.; Li, Y. Carbon pre-protected iron strategy to construct Fe, C-codoped g-C3N4 for effective photodegradation of organic pollutants via hole oxidation mechanism. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 437, 140739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, N.; Shi, X.; Chen, M.; Huang, Y.; Cao, J.; Li, H.; Ho, W.; Lee, S. Simultaneous polarization engineering and selectivity regulation achieved using polymeric carbon nitride for promoting NOx photo-oxidation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 330, 122582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Wei, Z.; Ding, M.; Li, Z.; Jia, J.; Zhou, M.; Yuan, L.; Bai, J.; Zhang, H. Enhanced photo-Fenton degradation of tetracycline using MIL-101 (Fe)/g-C3N4/FeOCl double Z-scheme heterojunction catalyst. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 688, 162386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Liu, X.; Huang, C.; Sun, H.; Subhan, F.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; et al. Nanoarchitectonics of MIL-101 (Fe)/g-C3N4 S-Scheme heterojunction for photocatalytic nitrogen fixation: Mechanisms and performance. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 53, 105083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagar, M.; Kumar, S.; Jain, A.; Singh, M.; Kundu, V. Study of Optical and Magnetic Properties of Solvothermally Synthesized Mn/Fe/N-Doped ZnO Nanocomposite for Advanced Dye Photodegradation. Phys. Solid State 2024, 66, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, X.Y.; Ji, Y.X.; Yang, Q.W.; Li, B.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, X. Fe-doped g-C3N4 with duel active sites for ultrafast degradation of organic pollutants via visible-light-driven photo-Fenton reaction: Insight into the performance, kinetics, and mechanism. Chemosphere 2024, 351, 141135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Li, J.; Pan, Y.; Li, X.; Zhuang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Luo, Q.; Chen, X. Fe-MOF nanoparticles supported with carbon-defective g-C3N4 nanosheet as visible-light driven photo-Fenton catalyst for efficient degradation of Tetracycline hydrochloride. Emergent Mater. 2025, 8, 4351–4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zheng, H.; Shen, X.; Hu, K.; Huang, W.; Liu, J. g-C3N4 Based Composite Materials for Photo-Fenton Reaction in Water Remediation: A Review of Synthesis Methods, Mechanism and Applications. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, e202400802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Sun, M.; Yu, H.; Su, L. Development of a g-C3N4-based photocatalysis-self-Fenton system for efficient degradation and mineralization of organic pollutants. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 367, 132833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Liang, Y.; Ding, C.; Jiang, Y.; Jin, H.; Rong, S.; Wu, J.; He, S.; Xia, C.; Xue, L. Sustainable design of photo-Fenton-like oxidation process in actual livestock wastewater through the highly dispersed FeCl3 anchoring on a g-C3N4 substrate. Water Res. 2024, 259, 121889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhaik, A.; Raizada, P.; Singh, P.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A.; Thakur, V.K.; Nguyen, V. Highly effective degradation of imidacloprid by H2O2/fullerene decorated P-doped g-C3N4 photocatalyst. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, W.; Ding, K. Synergistic Ag/g–C3N4 H2O2 system for photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes. Molecules 2024, 29, 3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Sui, Y.; Yao, Z.; Zhao, H.; Li, M.; Zou, L.; Yang, Y.; Hao, H.; Zhang, P.; Wang, H.; et al. Enhancing H2O2 synthesis in photocatalytic self-Fenton degradation of antibiotics by modulating surface hydrophobicity of Fe-doped g-C3N4 with ionic liquids. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Shu, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y. Photocatalytic degradation of sulfamethazine using g-C3N4/TiO2 heterojunction photocatalyst: Performance, mechanism insight and degradation pathway. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2024, 181, 108595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Xu, H.; Sun, S.; Zhao, Z.; Ren, X.; Li, M.; Song, B.; Shao, G.; Wang, H.; Lu, H. Facile synthesis of MgAl-LDH/g-C3N4 composites for the photocatalytic degradation toward ciprofloxacin. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Ahmed, M.A.; Mohamed, A.A. Fabrication of NiO/g-C3N4 Z-scheme heterojunction for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye. Opt. Mater. 2024, 151, 115339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Shao, Z.; Xie, L.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, K.; Chai, X. 0D/2D dual Fenton α-Fe2O3/Fe-doped g-C3N4 photocatalyst and the synergistic photo-Fenton catalytic mechanism insight. Chemosphere 2024, 358, 142158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Luo, P.; Gan, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Peng, H.; Peng, J. Efficient dual-channel photocatalytic H2O2 evolution and photocatalysis-self-Fenton process on defected carbon doped g-C3N4. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 649, 159118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Kodikara, D.; Albi, L.S.; Hatano, Y.; Chen, G.; Yoshimura, C.; Wang, J. Photodegradation of organic micropollutants in aquatic environment: Importance, factors and processes. Water Res. 2023, 231, 118236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göktaş, S. Synergic effects of pH, reaction temperature, and various light sources on the photodegradation of methylene blue without photocatalyst: A relatively high degradation efficiency. Chem. Afr. 2024, 7, 4425–4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Yang, S.; Wang, J.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Y. Plasma coupled with ultrasonic for degradation of organic pollutants in water: Revealing the generation of free radicals and the dominant degradation pathways. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 192, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permana, M.D.; Takei, T.; Khatun, A.A.; Eddy, D.R.; Saito, N.; Kumada, N. Effect of wavelength in light irradiation for Fe2+/Fe3+ redox cycle of Fe3O4/g-C3N4 in photocatalysis and photo-Fenton systems. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2024, 457, 115876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yang, Q.; Wen, Y.; Liu, W. Fe-g-C3N4/graphitized mesoporous carbon composite as an effective Fenton-like catalyst in a wide pH range. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 201, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liang, Y.; Yang, H.; An, S.; Shi, H.; Song, C.; Guo, X. New insight into the mechanism of enhanced photo-Fenton reaction efficiency for Fe-doped semiconductors: A case study of Fe/g-C3N4. Catal. Today 2021, 371, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.X.; Li, Z.H.; Xiao, R.S.; Wang, X.G.; Dai, H.L.; Tang, S.; Zheng, J.Z.; Yang, M.; Yuan, S.S. Real-time electrochemical monitoring sensor for pollutant degradation through galvanic cell system. Rare Met. 2025, 44, 1800–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamzeb, M.; Faryad, S.; Ullah, I.; Hussain, J.; Setzer, N.W. Photocatalytic Degradation of Brilliant Blue Dye Under Solar Light Irradiation: An Insight Into Mechanistic, Kinetics, Mineralization and Scavenging Studies. J. Fluoresc. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzam, M.M.; Labib, A.A.; Handal, H.T.; Mousa, H.A.; Galal, H.R.; Ibrahem, I.A.; Fawzy, M.M.; Ahmed, A.M.; Rwayhah, M.N.; Mohamed, A.A. Study of photophysical properties on recycling for solar and photo degradation process of Brilliant blue R dye and real industrial wastewater using Bentonite/TiO2 QDs. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2025, 314, 117991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, R.; Liang, H.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, G.; Yang, C. Fe-Doped g-C3N4 for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Brilliant Blue Dye. Water 2025, 17, 3220. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223220

Su R, Liang H, Jiang H, Zhang G, Yang C. Fe-Doped g-C3N4 for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Brilliant Blue Dye. Water. 2025; 17(22):3220. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223220

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Rongjun, Haoran Liang, Hao Jiang, Guangshan Zhang, and Chunyan Yang. 2025. "Fe-Doped g-C3N4 for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Brilliant Blue Dye" Water 17, no. 22: 3220. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223220

APA StyleSu, R., Liang, H., Jiang, H., Zhang, G., & Yang, C. (2025). Fe-Doped g-C3N4 for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Brilliant Blue Dye. Water, 17(22), 3220. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223220