The Effect of Irrigation and Vermicompost Applications on the Growth and Yield of Greenhouse Pepper Plants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Description

2.2. Experimental Method and Crop Management

2.3. Determination of the Irrigation Water Amount, Water Use Efficiency, and Yield Response Factor

2.4. Soil and Water Analyses

2.5. Plant Growth and Quality Measurements and Analyses

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Plant Growth Parameters of Pepper

3.2. Quality Parameters of the Pepper

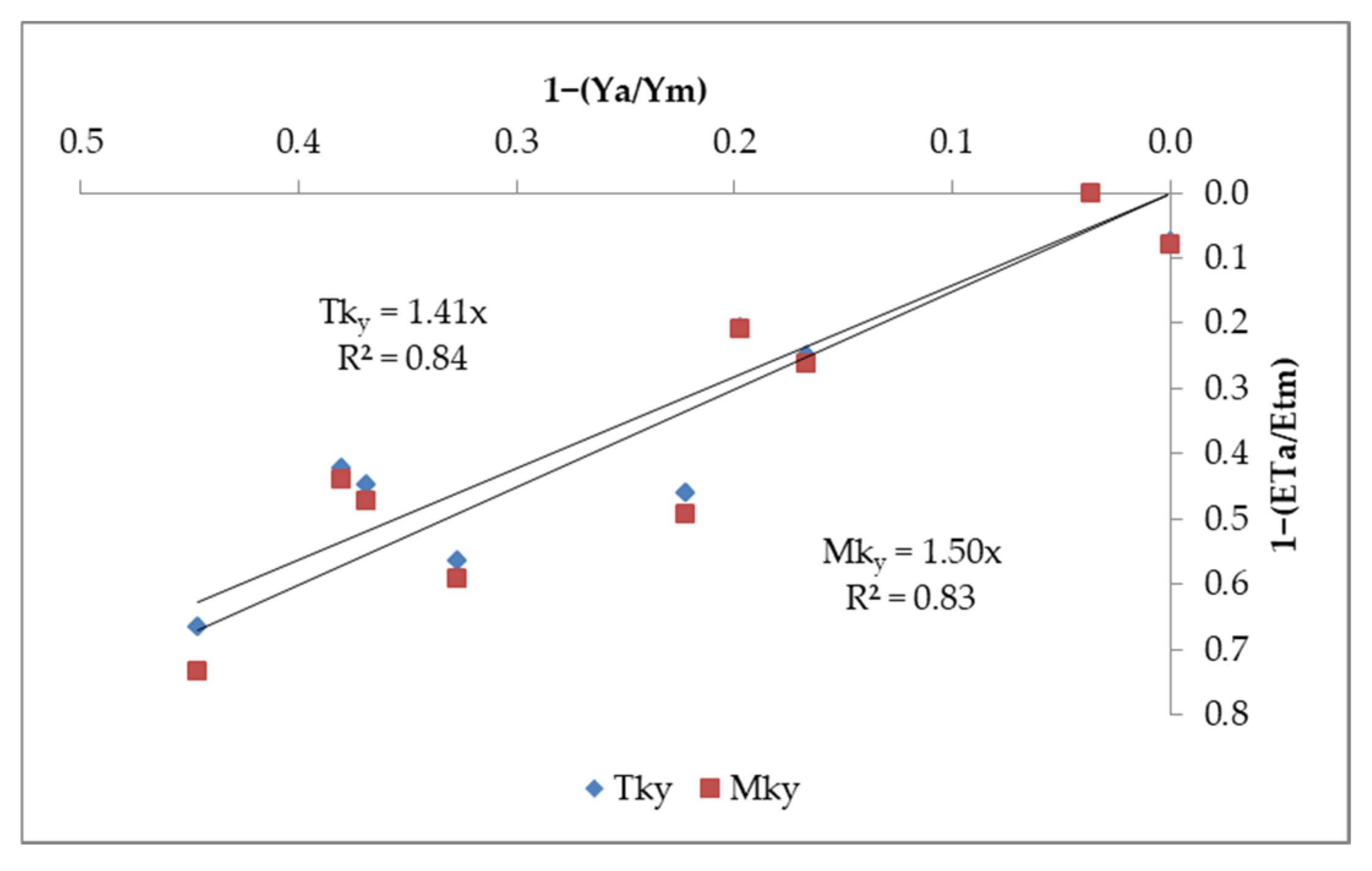

3.3. Water Consumption Amount and Yield Relationships

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bahraseman, S.E.; Firoozzare, A.; Boccia, F.; Pourmohammad, F.; Ameri, A.H. Determining the best strategies to improve agricultural water productivity in arid and semi-arid regions: An ordinal priority approach. J. Arid. Environ. 2025, 231, 105458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Hoque, M.R.; Hassan, A.A.; Khair, A. Effects of deficit irrigation on yield, water productivity, and economic returns of wheat. Agric. Water Manag. 2007, 92, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, S.; Raes, D. Deficit irrigation as an on-farm strategy to maximize crop water productivity in dry areas. Agric. Water Manag. 2009, 96, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivushkin, K.; Bartholomeus, H.; Bregt, A.K.; Pulatov, A.; Kempen, B.; de Sousa, L. Global mapping of soil salinity change. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 231, 111260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tang, H.M.; Du, H.; Bao, Z.L.; Shi, Q.H. Sugar metabolic and N-glycosylated profiles unveil the regulatory mechanism of tomato quality under salt stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 177, 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.S.; Zhang, Q.K.; Liu, M.Y.; Zhou, H.P.; Ma, C.L.; Wang, P.P. Regulation of plant responses to salt stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Ju, J.; Zhao, H.; Bhatti, S.M.; Saleem, G.; Memon, S.P.; Ali, S.; Younas, M.U.; Rajput, N.; Jamali, Z.H. Morphological and Physiological Response of Tomato to Sole and Combined Application of Vermicompost and Chemical Fertilizers. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiach, R.; Canet, R.; Pomares, F.; Ingelmo, F. Microbial biomass content and enzymatic activities after the application of organic amendments to a horticultural soil. Bioresour. Technol. 2000, 75, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, O.H.; Persaud, N.; Martens, D.C. Effect of long-term application of animal manure on physical properties of three soils. Plant Soil. 1995, 176, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.H.; Haynes, R.J.; Meyer, J.H. Soil organic matter content and quality: Effects of fertilizer applications, burning and trash retention on a long-term sugarcane experiment in South Africa. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wang, D.; Sun, Y. Analysis of antagomistic microorganism in vermicompost. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2004, 10, 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, F.H.; Cegarry, J.; Trrujillo, L.M.; Roig, A. Vermicomposting of coffee pulp using the earthworm Eisenia fetida: Effects on C and N contents and the availability of nutrients. Biol. Fertil Soils 1996, 22, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, E.; Ozen, N.; Ozen, M. Determination of changes in yield and quality of tomato seedlings (Solanum lycopersicon cv. Sedef F1) in different soilless growing media. Mediterr. Agric. Sci. 2017, 30, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bellitürk, K. Vermicomposting in Turkey: Challenges and opportunities in future. Eurasian J. For. Sci. 2018, 6, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossuyt, H.; Six, J.; Hendrix, P.F. Protection of soil carbon by microaggregates within earthworm casts. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2005, 37, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, M.; González, J.L. Application of two vermicomposts on a rice crop: Effects on soil biological properties and rice quality and yield. Agron. J. 2009, 101, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, D.; Bosland, P.W. The Pepper Garden; Ten Speed Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mačkić, K.; Bajić, I.; Pejić, B.; Vlajić, S.; Adamović, B.; Popov, O.; Simić, D. Yield and water use efficiency of drip irrigation of pepper. Water 2023, 15, 2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorenbos, J.; Kassam, A.H. Yield Response to Water; Irrigation and Drainage Paper 1986, No. 33; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1979; p. 193. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, A.; Lovelli, S.; Di Tommaso, T.; Perniola, M. Flowering, growth and fruit setting in greenhouse bell pepper under water stress. J. Agron. 2011, 10, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürgülü, H.; Ul, M.A. Different effects of irrigation water salinity and leaching fractions on pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) cultivation in soilless culture. Agriculture 2024, 14, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covino, D.; Boccia, F. Environmental management and global trade’s effects. Qual.—Access Success. 2014, 15, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Meena, R.P.; Sharma, R.K.; Chhokar, R.S.; Chander, S.; Tripathi, S.C.; Kumar, R.; Sharma, I. Improving water use efficiency of rice-wheat cropping system by adopting micro-irrigation systems. Int. J. Bio-Resour. Stress. Manag. 2015, 6, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, E.; Singandhupe, R.B. Impact of drip and surface irrigation on growth, yield and WUE of capsicum (Capsicum annum L.). Agric. Water Manag. 2004, 65, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurunc, A.; Ünlükara, A.; Cemek, B. Salinity and drought affect yield response of bell pepper similarly. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B Soil. Plant Sci. 2011, 61, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünlükara, A.; Kurunc, A.; Cemek, B. Green Long Pepper Growth under Different Saline and Water Regime Conditions and Usability of Water Consumption in Plant Salt Tolerance. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 21, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.D.; Gianquinto, G. Water stress and water table depth influence yield, water use efficiency, and nitrogen recovery in bell pepper: Lysimeter studies. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2002, 53, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arancon, N.Q.; Edwards, C.A.; Bierman, P.; Metzger, J.D.; Lucht, C. Effects of vermicomposts produced from cattle manure, food waste and paper waste on the growth and yield of peppers in the field. Pedobiologia 2005, 49, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshnauth, V.; Jaikishun, S.; Ansari, A.A.; Homenauth, O. The effect of vermicompost and other fertilizers on the growth and productivity of pepper plants in guyana. Autom. Agric.-Secur. Food Supplies Future Gener. 2018, 3, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Şenyiğit, U.; Toprak, M.; Çoşkan, A. The effects of different irrigation levels and vermicompost doses on evapotranspiration and yield of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) under glasshouse conditions. Türk Bilim. Mühendislik Derg. 2021, 3, 37–43, (In Turkish with English Abstract). [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Coşkan, A.; Şenyiğit, U. Farklı sulama suyu düzeyi ve vermikompost dozlarının marul bitkisinin mikro element alımına etkileri. Ziraat Fakültesi Dergisi. 2018, 348–356. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/sduzfd/issue/40528/458566 (accessed on 15 October 2023).[Green Version]

- Demir, Z. Effects of vermicompost on soil physicochemical properties and lettuce (Lactuca sativa Var. Crispa) yield in greenhouse under different soil water regimes. Commun. Soil. Sci. Plant Anal. 2019, 50, 2151–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llaven, M.A.O.; Jimenez, J.L.G.; Coro, B.I.C.; Rincón-Rosales, R.; Molina, J.M.; Dendooven, L.; Gutiérrez-Miceli, F.A. Fruit characteristics of bell pepper cultivated in sheep manure vermicompost substituted soil. J. Plant Nutr. 2008, 31, 1585–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piri, H.; Naserin, A.; Albalasmeh, A.A. Interactive effects of deficit irrigation and vermicompost on yield, quality, and irrigation water use efficiency of greenhouse cucumber. J. Arid. Land. 2022, 14, 1274–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meteoroloji Genel Müdürlüğü. Climate Kırşehir (Turkey). Available online: https://www.mgm.gov.tr/veridegerlendirme/il-ve-ilceler-istatistik.aspx?m=KIRSEHIR (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- USSL. Diagnoses and Improvement of Saline and Alkali Soils; Richards, L.A., Ed.; United State Salinity Laboratory Staff, USDA_SCS, Agric. Handbook no. 60; USSL: Washington, DC, USA, 1954; 160p.

- Colimba-Limaico, J.E.; Zubelzu-Minguez, S.; Rodríguez-Sinobas, L. Optimal irrigation scheduling for greenhouse tomato crop (Solanum lycopersicum L.) in Ecuador. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyoucus, G.Y. A Calibaration of the hydrometer for making mechanical analysis of soils. Agron. J. 1951, 43, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, G.R.; Hartge, K.H. Bulk Density. In Methods of Soil Analysis; Klute, A., Ed.; Part 1—Physical and Mineralogical Methods Second Edition; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades, J.; Chandavi, D.; Lesch, S.F. Soil Salinity Assessment Methods and Interpretation of Electrical Conductivity Measurement; FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 57; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- USDA. Soil Survey Staff; Soil Survey Manuel; USDA Handbook; No: 18; USDA: Washington DC, USA, 1993.

- Olsen, S.R.; Cole, V.; Watanabe, F.S.; Dean, L.A. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington DC, USA, 1954.

- Jackson, M.L. Soil Chemical Analysis; Prentice Hall of India Private Limited: New Delhi, India, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2. Chemical and Microbiological Properties, 2nd ed.; Page, A.L., Miller, R.H., Keeney, D.R., Eds.; Academic Press, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Eltan, E. Içme ve Sulama Suyu Analiz Yöntemleri. Ba¸sbakanlık Köy Hizmetleri Genel Müdürlüğü Yayın Evi, Ankara, 109 sy. 1998. Available online: https://kutuphane.tarimorman.gov.tr/vufind/Record/15528 (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- ICS 67.080.20; Taze Biber Türk Standardı 1205. TSE: Ankara, Turkey, 1974.

- Gutiérrez-Miceli, F.A.; Santiago-Borraz, J.; Molina, J.A.M.; Nafate, C.C.; Abud-Archila, M.; Llaven, M.A.O.; Rincón-Rosales, R.; Dendooven, L. Vermicompost as a soil supplement to improve growth, yield and fruit quality of tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum). Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 2781–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyacı, S.; Kocięcka, J.; Kęsicka, B.; Atılgan, A.; Liberacki, D. Assessment of the Crop Water Stress Index for Green Pepper Cultivation Under Different Irrigation Levels. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyacı, S.; Kocięcka, J.; Atilgan, A.; Niemiec, M.; Liberacki, D.; Rolbiecki, R. Determination of the Effects of Different Irrigation Levels and Vermicompost Doses on Water Consumption and Yield of Greenhouse-Grown Tomato. Water 2024, 16, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL-Mogy, M.M.; Adly, M.A.; Shahein, M.M.; Hassan, H.A.; Mahmoud, S.O.; Abdeldaym, E.A. Integration of Biochar with Vermicompost and Compost Improves Agro-Physiological Properties and Nutritional Quality of Greenhouse Sweet Pepper. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin Kabir, M.; Nambeesan, S.U.; Bautista, J.; Díaz-Pèrez, J.C. Effect of irrigation level on plant growth, physiology and fruit yield and quality in bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Sci. Hortic. 2021, 281, 109902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaboz, P.; Işıldar, A.A.; Müjdeci, M.; Şenol, H. Effects of different vermicompost and soil moisture levels on pepper (capsicum annuum) grown and some soil properties. Yuz. Yıl Univ. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 27, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarideljou, M.J.; Heidari, Z. Effects of vermicompost on growth parameters, water use efficiency and quality of zinnia bedding plants (Zinnia elegance ‘Dreamland Red’) under different ırrigation regimes. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2014, 1, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-Albores, J.M.; Montes-Molina, J.A.; Castañón-González, J.H.; Abud-Archila, M.; Gutiérrez-Miceli, F.A.; Ruíz-Valdiviezo, V.M. Effect of different vermicompost doses and water stress conditions on plant growth and biochemical profile in medicinal plant, Moringa oleifera Lam. J. Environ. Biol. 2020, 41, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najar, I.A.; Khan, A.B.; Hai, A. Effect of macrophyte vermicompost on growth and productivity of brinjal (Solanum melongena) under field conditions. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2015, 4, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batu, A. Determination of acceptable firmness and colour values of tomatoes. J. Food Eng. 2004, 61, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A. Understanding Food Principles and Preparation; Thomson Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 245–266. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.Y.; Lin, S.S. Compost as soil supplement enhanced plant growth and fruit quality of strawberry. J. Plant Nutr. 2002, 25, 2243–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Perez, T.; Carrillo-Lopez, A.; Guevara-Lara, F.; Cruz-Hernandez, A.; Paredes-Lopez, O. Biochemical and nutritional characterization of three prickly pear species with different ripening behavior. Plant Food Hum. Nutr. 2005, 60, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.A.; Duarte, S.N.; Medeiros, J.F.; Aroucha, E.M.M.; Dias, N.S. Quality in the pepper under different fertigation managements and levels of nitrogen and potassium. Rev. Ciência Agronômica 2015, 46, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, Q.; Liu, Y. Water requirement of solar greenhouse tomatoes with drip irrigation under mulch in the Southwest of the Taklimakan Desert. Water 2022, 14, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, B.L.R.; Araujo, R.H.C.R.; Rocha, J.L.A.; Silva, T.I.; Alves, K.A.; Almeida, E.S.; Ferreira, K.N. Zinc oxide nanoparticles and bioinoculants on the postharvest quality of eggplant subjected to water deficit. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agric. Amb. 2024, 28, e279019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierson, D.; Kader, A.A. Fruit ripening and quality. In The Tomato Crop. The Tomato Crop; Atherton, J.G., Rudich, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt Çolak, Y.; Yazar, A.; Yıldız, M.; Tekin, S.; Gönen, E.; Alghawry, A. Assessment of crop water stress index and net benefit for surface- and subsurface-drip irrigated bell pepper to various deficit irrigation strategies. J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 161, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matas, A.J.; Gapper, N.E.; Chung, M.-Y.; Giovannoni, J.J.; Rose, J.K.C. Biology and genetic engineering of fruitmaturation for enhanced quality and shelf-life. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2009, 20, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, S.; Kaur, N. Impact of Vermicompost on Growth, Yield and Quality of Tomato Plant (Lycopersicum esculentum). J. Adv. Lab. Res. Biol. 2012, 3, 281–284. [Google Scholar]

- Candemir, F.; Gülser, C. Effects of different agricultural wastes on some soil quality indexes in clay and loamy sand fields. Commun. Soil. Sci. Plant Anal. 2011, 42, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhawary, S.M.A.; Ordóñez-Díaz, J.L.; Nicolaie, F.; Montenegro, J.C.; Teliban, G.C.; Cojocaru, A.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M.; Stoleru, V. Quality responses of sweet peppervarieties underirrigation and fertilization regimes. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Jolaini, M. Evaluation of agricultural water productivity indices in major field crops in Mashhad plain. J. Water Sustain. Dev. 2017, 4, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, A.; Kundu, M.; Sarkar, S. Role of irrigation and mulch on yield, evapotranspiration rate and water use pattern of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.). Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 98, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.S.; Oweis, T.; Zairi, A. Irrigation management under water scarcity. Agric. Water Manag. 2002, 57, 175–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladenola, O.; Madramootoo, C. Response of greenhouse-grown bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) to variable irrigation. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 94, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.S.S.; Soares, P.R.; Guilherme, R.; Vitali, G.; Boulet, A.; Harrison, M.T.; Malamiri, H.; Duarte, A.C.; Kalantari, Z.; Ferreira, A.J.D. Sustainable water management in horticulture: Problems, premises, and promises. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locascio, S.J.; Smajstrla, A.G. Water application scheduling by pan evaporation for drip-irrigated tomato. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1996, 121, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, S.; Kuşçu, H. Water-yield relationships of green pepper (Capsicum annuum) cultivated at different irrigation levels. J. Agric. Fac. Bursa Uludag Univ. 2024, 38, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gençoğlan, C.; Akıncı, I.E.; Uçan, K.; Akıncı, S.; Gençoğlan, S. Response of red hot pepper plant (Capsicum annuum L.) to the deficit irrigation. Akdeniz Üniversitesi Ziraat Fakültesi Derg. 2006, 19, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kirda, C. Deficit irrigation scheduling based on plant growth stages showing water stress tolerance. In FAO, Deficit Irrigation Practices; FAO Water Report No. 22; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2002; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

| Sensor Locations | Parameters | May | June | July | Aug. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outside | Tmean, °C | 15.2 | 20.4 | 22.2 | 20.6 |

| RHmean, % | 61.2 | 59.5 | 51.0 | 51.6 | |

| Inside | Tmean, °C | 23.8 | 27.2 | 28.4 | 24.4 |

| RHmean, % | 47.0 | 52.3 | 41.5 | 58.6 |

| Properties | Soil | Vermicompost |

|---|---|---|

| Soil texture | Sandy clay-loam (SCL) | |

| Sand (%) | 70.9 | |

| Clay (%) | 21.08 | |

| Silt (%) | 8.02 | |

| Bulk density (g cm−3) | 1.27 | |

| pH | 8.44 | 8.27 |

| EC (µS cm−1) | 135.7 | 13300 |

| CaCO3 (%) | 41.9 | 5.99 |

| OM (%) | 2.65 | 37.11 |

| Available P2O5 (kg da−1) | 8.70 | 379.42 |

| Available K2O (kg da−1) | 72.0 | 3726.56 |

| pH | EC, dS m−1 | Anions, meq L−1 | Cations, meq L−1 | SAR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | Mg | K | Na | CO3 | HCO3 | Cl | SO4 | |||

| 7.70 | 0.62 | 2.8 | 1.20 | 0.05 | 1.40 | 0 | 5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.40 |

| Growth Stages of Pepper Plant | VD0 | VD10 | VD20 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL100 | IL75 | IL50 | IL100 | IL75 | IL50 | IL100 | IL75 | IL50 | |

| Planting | May 5 | May 5 | May 5 | May 5 | May 5 | May 5 | May 5 | May 5 | May 5 |

| First Flowering of pepper | May 24 | May 25 | May 27 | May 22 | May 24 | May 25 | May 19 | May 20 | May 22 |

| Pepper fruit setting | Jun. 5 | Jun. 7 | Jun. 10 | Jun. 2 | Jun. 6 | Jun. 9 | Jun. 1 | Jun. 3 | Jun. 8 |

| First harvesting of pepper | Jul. 11 | Jul. 13 | Jul. 20 | Jul. 9 | Jul. 14 | Jul. 18 | Jul. 6 | Jul. 10 | Jul. 16 |

| Last harvesting of pepper | Aug. 8 | Aug. 8 | Aug. 8 | Aug. 8 | Aug. 8 | Aug. 8 | Aug. 8 | Aug. 8 | Aug. 8 |

| Treatments | Stem Diameter (mm) | Plant Height (cm) | Number of Leaves (Pieces) | Stem Fresh Weight (g) | Stem Dry Weight (g) | Root Fresh Weight (g) | Root Dry Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL50–VD0 | 6.4 d | 27.3 e | 56.2 e | 35.2 d | 21.8 e | 35.1 de | 23.6 b |

| IL75–VD0 | 6.7 cd | 31.7 d | 48.2 e | 35.4 d | 23.2 e | 32.0 e | 19.1 c |

| IL100–VD0 | 7.0 cd | 32.3 d | 37.2 f | 33.7 d | 22.5 e | 32.9 de | 14.0 d |

| IL50–VD10 | 6.8 cd | 35.2 cd | 83.7 c | 58.1 c | 26.7 d | 43.7 c | 24.4 b |

| IL75–VD10 | 8.6 ab | 41.5 b | 81.8 c | 75.0 b | 30.9 b | 52.3 ab | 27.2 a |

| IL100–VD10 | 8.8 a | 48.0 a | 72.3 d | 62.5 c | 28.7 c | 57.1 a | 19.0 c |

| IL50–VD20 | 7.1 cd | 38.7 bc | 94.3 b | 80.9 b | 29.0 c | 38.6 cde | 22.0 b |

| IL75–VD20 | 8.4 ab | 47.0 a | 108.0 a | 100.1 a | 32.8 a | 45.5 bc | 24.3 b |

| IL100–VD20 | 7.6 bc | 39.7 bc | 96.8 b | 55.6 c | 25.2 c | 39.8 cd | 14.6 d |

| IL | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | NS | ** |

| VD | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| IL × VD | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | * | ** |

| Treatments | Fruit Width (mm) | Fruit Length (mm) | Fruit Weight (g) | Fruit Flesh Thickness (mm) | pH | TA (%) | TSS (°Brix) | Chrome | Hue (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL50–VD0 | 17.3 c | 14.9 bcd | 10.0 c | 2.6 bc | 5.7 ab | 1.2 a | 5.4 a | 38.0 c | 116.7 c |

| IL75–VD0 | 19.1 bc | 13.6 de | 11.8 bc | 2.0 c | 5.7 ab | 1.0 a | 5.2 a | 42.7 bc | 121.6 abc |

| IL100–VD0 | 18.0 c | 13.1 de | 13.1 bc | 2.5 bc | 5.8 ab | 1.1 a | 4.2 d | 45.5 ab | 117.3 bc |

| IL50–VD10 | 17.3 c | 13.9 cde | 12.6 bc | 2.3 bc | 5.9 a | 1.0 a | 4.8 b | 31.5 d | 124.6 a |

| IL75–VD10 | 19.7 bc | 15.7 bc | 16.4 b | 2.7 ab | 5.8 ab | 0.9 a | 4.2 d | 31.6 d | 124.5 a |

| IL100–VD10 | 21.9 ab | 16.4 ab | 23.0 a | 3.2 a | 5.7 ab | 0.8 a | 4.0 d | 50.0 a | 118.3 bc |

| IL50–VD20 | 17.0 c | 12.7 e | 12.5 bc | 2.4 bc | 5.7 ab | 0.9 a | 5.3 b | 25.6 d | 125.8 a |

| IL75–VD20 | 18.4 c | 15.6 bc | 16.8 b | 2.1 bc | 5.6 ab | 0.9 a | 4.9 b | 26.5 d | 122.7 ab |

| IL100–VD20 | 23.5 a | 17.8 a | 26.7 a | 2.5 bc | 5.5 b | 0.9 a | 4.5 c | 46.4 ab | 121.1 abc |

| IL | ** | ** | ** | * | NS | ** | ** | ** | * |

| VD | NS | ** | ** | * | * | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| IL × VD | * | ** | * | NS | NS | ** | ** | ** | NS |

| Treatments | ET (L) | TY (g pot−1) | MY (g pot−1) | TWUE (g L−1) | MWUE (g L−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL50–VD0 | 15.4 h | 55.2 e | 39.6 e | 3.6 b | 2.6 c |

| IL75–VD0 | 18.7 f | 71.8 de | 61.1 de | 3.8 b | 3.3 c |

| IL100–VD0 | 21.6 e | 88.7 d | 76.0 d | 4.1 b | 3.5 bc |

| IL50–VD10 | 17.5 g | 91.0 d | 78.9 d | 5.2 a | 4.5 ab |

| IL75–VD10 | 23.2 c | 123.3 c | 110.4 c | 5.3 a | 4.8 a |

| IL100–VD10 | 27.8 a | 152.2 ab | 137.8 ab | 5.5 a | 5.0 a |

| IL50–VD20 | 17.2 g | 95.0 d | 83.7 d | 5.5 a | 4.9 a |

| IL75–VD20 | 22.3 d | 130.5 bc | 118.5 bc | 5.9 a | 5.3 a |

| IL100–VD20 | 26.8 b | 164.5 a | 149.8 a | 6.1 a | 5.6 a |

| IL | ** | ** | ** | NS | NS |

| VD | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| IL × VD | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boyacı, S.; Atilgan, A.; Rolbiecki, R.; Kocięcka, J. The Effect of Irrigation and Vermicompost Applications on the Growth and Yield of Greenhouse Pepper Plants. Water 2025, 17, 3219. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223219

Boyacı S, Atilgan A, Rolbiecki R, Kocięcka J. The Effect of Irrigation and Vermicompost Applications on the Growth and Yield of Greenhouse Pepper Plants. Water. 2025; 17(22):3219. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223219

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoyacı, Sedat, Atilgan Atilgan, Roman Rolbiecki, and Joanna Kocięcka. 2025. "The Effect of Irrigation and Vermicompost Applications on the Growth and Yield of Greenhouse Pepper Plants" Water 17, no. 22: 3219. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223219

APA StyleBoyacı, S., Atilgan, A., Rolbiecki, R., & Kocięcka, J. (2025). The Effect of Irrigation and Vermicompost Applications on the Growth and Yield of Greenhouse Pepper Plants. Water, 17(22), 3219. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223219