1. Introduction

The rapid growth of aquaculture is in line with increasing food demand globally. Based on the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) data, the apparent consumption of aquatic animal food in 2022 is 164.6 million tons. Effort are being made to fulfill this meet, one of them is using aquaculture. The inland and marine aquaculture contribute approximately 51% of the total production in the same year. This production was supported by a 7.8% increase in production of inland aquaculture from 2020 to 2022 [

1]. However, the aquaculture system also has some challenges such as the excessive usage of water and electricity, and the potential risk of environment contamination. One of the ways to maintain aquaculture sustainability is using the recirculating aquaculture system (RAS). The RAS operates as a closed-loop system capable of recycling 90–99% of its water through a combined biological and mechanical filtration process. The system incorporates precise control of key environment parameters, thereby minimizing the risk of disease outbreaks compared to conventional open systems [

2]. Despite the benefit of the RAS, one of the main problems that affects water quality and ensures the health of aquaculture species in RAS is the maximum level of Total Ammonia Nitrogen (TAN). TAN is combination of

(ammonia) and

(ammonium) which is produced from feed residue and aquaculture excretory systems [

3]. TAN accumulation represents a significant challenge in the RAS, as excessive TAN levels can cause stress and sublethal effects in cultured species. Therefore, an effective biotechnological process is required within RAS to reduce the TAN to safe concentration levels. This process relies on nitrifying bacteria within the biofilter which converts ammonia to less toxic compounds through the nitrification process under aerobic conditions [

4]. Biofilters can be classified into two types: a suspended growth system and an attached growth system [

5]. In a suspended growth system, the bacteria will remain suspended in the wastewater through the mixing process and the waste flow will be collected into flocs with the help of the microorganism [

6]. Whereas, in the attached growth or fixed film, the microorganism will attach and grow to form biofilm on a solid surface [

7]. Biochemical reactions such as oxidation and nitrification work to convert pollutant into stable forms that occur within the biofilm layer.

Moving bed biofilm reactor (MBBR) is a type of biofilter that utilizes an attached growth system. Biofilm grows in small media (biocarrier) that moves inside the MBBR due to the presence of high-pressure air, the speed of the water, or because of the stirring process. This can increase the concentration of active biomass without increasing the size of the reactor [

8]. MBBR utilizes nitrifying bacteria that grow in the biocarrier to degrade TAN in the system. In the nitrification process, media circulation is regulated by an aeration system to create aerobic conditions. So, selecting an aeration system is important in improving the performance of the MBBR.

The bubble aeration system uses air or gas in the form of bubbles to stir or accelerate biofilm growth. Based on bubble size, bubble aeration can be categorized as a nanobubble (diameter ≤ 1 µm), fine bubble (diameter ≤ 100 µm), microbubble (1–100 µm), medium bubble (1.5–3 mm) or as coarse bubbles (diameter ≥ 3 mm) [

9,

10]. The bubble aeration can be supplied using a diffuser and the size of the bubbles produced depends on the morphology of the diffuser [

11]. In a bubble diffuser, air supplied through the fine pores of the diffuser forms bubbles that rise through the water column. The relative motion between bubbles and water enhances contact, promoting oxygen transfer across the liquid film boundary into the water as dissolved oxygen (DO) [

12].

Bubble aeration is an important parameter for biofilm growth related to TAN degradation in RAS, a study was conducted to investigate the mass transfer of nanobubble aeration and its influence on biofilm growth. The study used a lab scale membrane filter and resulted in 75% TAN removal with 1188 ± 322 µm biofilm thickness [

13]. Another study investigated the influence of five different media in the start-up phase of MBBR. Coarse bubble aeration was used in the study and achieved 64 ± 13% of TAN removal efficiency with 71 ± 22 µm biofilm thickness with spherical shape biocarrier [

14]. Whereas the combination of nanobubble generator and coarse bubble diffuser was used as an aeration system in biological aerated filters (BAF). Maximum biofilm thickness of 136.1 µm with highest TAN removal of 89.22% was achieved in this study [

15]. The results of the study show that biofilm thickness is related to the TAN removal efficiency.

Although nanobubbles have been reported to enhance oxygen transfer and pollutant removal in laboratory-scale bioreactors, few studies have systematically examined their influence on biofilm structure and nitrification performance in pilot-scale systems. This study aims to fill this gap by evaluating biofilm development, microbial activity, and total ammonia nitrogen (TAN) removal in a pilot-scale moving bed biofilm reactor (MBBR) operated under nanobubble and coarse-bubble aeration. Unlike most previous studies which focused solely on micro-scale mechanisms, the present work investigates nanobubble aeration in a pilot-scale MBBR fed with synthetic wastewater containing NH4Cl and glucose, formulated to simulate the nutrient composition and organic loading of the typical recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) effluents. The study provides an integrated analysis of biofilm morphology, composition, and nitrification behavior, thereby bridging the gap between mechanistic nanobubble research and its potential application in engineered biological treatment systems.

The objectives of this study are to (i) evaluate the effect of nanobubble aeration on biofilm growth and TAN removal in a pilot-scale MBBR fed with synthetic wastewater, (ii) compare the structural and compositional characteristics of the biofilms developed under nanobubble and coarse-bubble aeration using FTIR, SEM, and EDX analyses, and (iii) assess the operational feasibility and potential scalability of nanobubble aeration for improving nitrification performance in biofilm-based treatment systems. We hypothesize that nanobubble aeration enhances biofilm growth and nitrification efficiency by improving oxygen and nutrient transfer at the biofilm–water interface compared with coarse-bubble aeration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Pilot of RAS

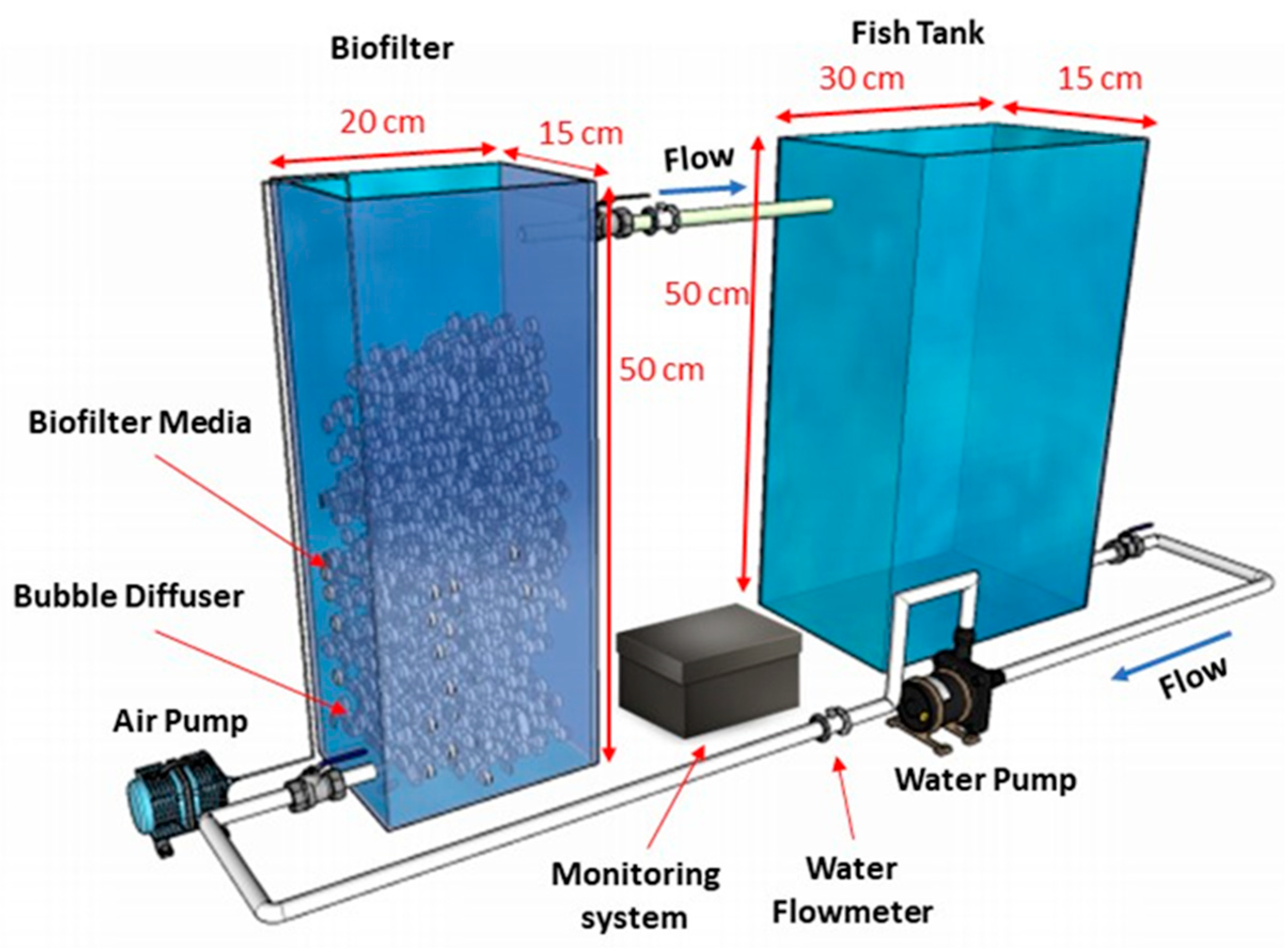

The schematic of the pilot-scale moving bed biofilm reactor (MBBR) system, under nanobubble and coarse-bubble aeration systems, in

Figure 1 consists of MBBR with a working volume of 12 L and a fishtank with a working volume of 24 L. Inside the MBBR, K1 Kaldness with a surface area of 800 m

2/m

3 and a diameter of 10 mm is used as biocarrier. The biocarrier filled 40% of the MBBR working volume. The system also consists of a water pump for recirculation and an aeration pump as air supply for the bubble diffuser. The aeration rate was set at 0.4 L/min during the period of the experiment.

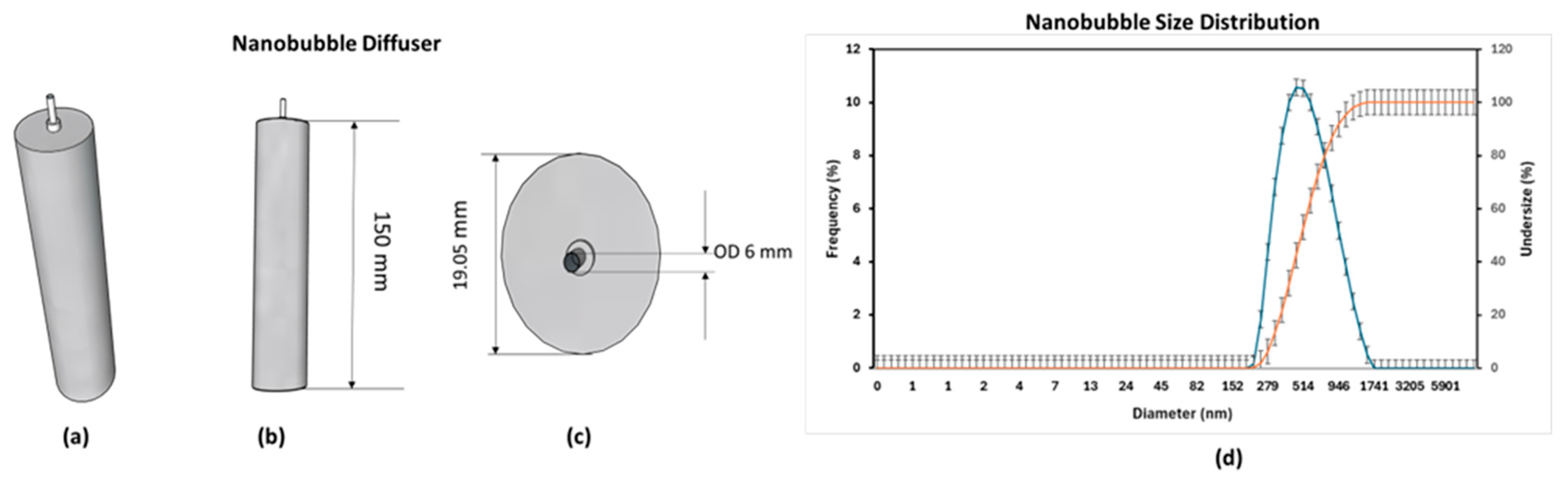

Figure 2 presents the nanobubble diffuser employed in this study, showing (a) a 3D view, (b) the front view, (c) the top view, and (d) the bubble size distribution generated by the diffuser. The diffuser was specifically designed to promote efficient air–water mixing and shear-induced cavitation for nanobubble formation. The bubble size distribution was analyzed using a Zetasizer 100 (Horiba, Kyoto, Japan) based on dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements. As shown in

Figure 2d, the generated bubbles exhibited a unimodal distribution with an average diameter of approximately 555 nm, confirming their classification as nanobubbles (≤1 µm) according to ISO 20480-1:2017 [

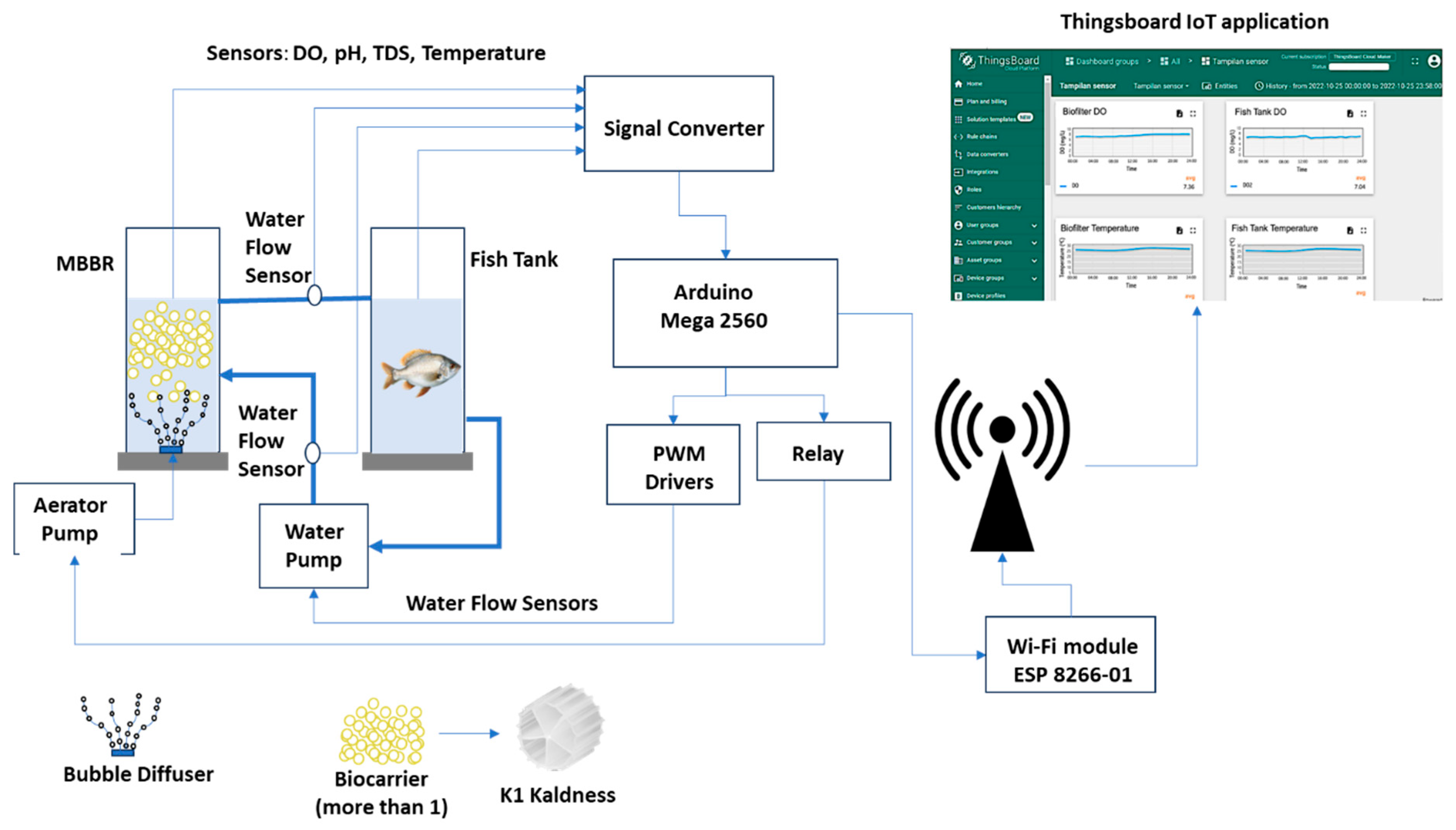

9]. The narrow size distribution and stable peak indicate that the diffuser consistently produced nanoscale bubbles, which were expected to enhance oxygen mass transfer and support more effective biofilm aeration compared with conventional coarse bubbles. Also, an aerator stone with a diameter of 35 mm was used for comparison as source of coarse bubble. Besides the main component, this system was also equipped with an IoT system consisting of a water parameter sensor, a microcontroller Arduino Mega 2560, and an IoT platform Thingsboard as a real time monitoring system (

Figure 3). The water quality parameter data were measured every one minute and the average was taken every day for analysis, which was carried out for 35 days.

2.2. Methodology

The reactor was fed with synthetic wastewater which was prepared by adding 0.151 g of NH

4Cl and 1.51 g of glucose to simulate ammonia and organic loading conditions similar to those found in freshwater recirculating aquaculture systems (salinity < 0.5 ppt, pH 7.3 ± 0.2). Under these conditions, freshwater ammonia-oxidizing (

Nitrosomonas spp.) and nitrite-oxidizing (

Nitrobacter spp.) bacteria were expected to dominate the nitrification process. In the experiment, 10 mL of

Nitrosomonas and

Nitrobacter were added as bacteria starters. The bacteria were cultured into the system to form a biofilm layer on Kaldness K1 biocarrier. This waste was added every day to produce 2 mg/L of TAN per day. Ammonium underwent oxidation to become nitrite (

) with the help of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB), such as

Nitrosomonas. Then, nitrite was converted into nitrate (

) with the help of nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB), such as

Nitrobacter, as can be seen in the reactions in Equations (1) and (2) [

16]. (

) at certain levels, even up to 200 mg/L, is not very dangerous when compared to TAN and nitrite [

17], so the nitrification process is very necessary for water treatment in RAS.

The measurement of TAN, nitrite, and nitrate was carried out by mixing 5 mL of the sample with the reagent and comparing it with a standardized color chart to determine test values, which served as indicators of water quality. Sampling was carried out before and after adding the synthetic waste, so that the TAN degradation could be determined. TAN degradation efficiency can be calculated using Equation (3), where TANdeg is the TAN degradation in one day, and TANs is the TAN degradation on the previous day after adding synthetic waste [

18].

The operational parameters for the experiment are presented in

Table 1. All operational parameters were monitored using an IoT-based digital measurement system with calibrated sensors for real-time data acquisition. The accuracy of the results is based on instrument precision rather than repeated manual sampling. The two aeration conditions (nanobubble and coarse-bubble) were conducted sequentially under identical operating conditions and data were continuously recorded and analyzed from the digital monitoring system.

2.3. Biofilm Thickness Measurement

Biofilm thickness measurements were carried out using adaptation of the gravimetric method [

19]. The measurements were carried out every 7 days during the experiment. The biocarrier sample was collected in a container and dried, then weighed (mass X). The sample was then dried at a temperature of 65 °C for 24 h, then weighed (mass Y). After that, the sample was put into the MilliQ and separated using a magnetic stirrer, then brushed so that the biofilm was separated from the surface of the biocarrier and then weighed (mass Z). The wet mass (

) was obtained from the difference between X and Z. Whereas, the dry mass (

) was calculated from the difference in Y and Z. Biofilm thickness (

) was calculated from Equation (4), where

(cm

2/cm

3) is the surface area of biocarrier and

is the density of wet biofilm (1 g/cm

3).

2.4. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Analysis

FTIR characterization was carried out to determine the functional groups contained in the biofilm. Three samples, biocarrier without biofilm, biocarrier with biofilm using nanobubble aeration, and biocarrier with biofilm using coarse bubble aeration treatment, were taken for FTIR analysis. Biocarrier with biofilm samples were collected from the MBBR at the end of the experiment. The samples were dried at a temperature of 65 °C for 24 h. The samples were then analyzed using FTIR with a range of 4000–400 cm−1.

2.5. Bacteria Identification

The Total Plate Count (TPC) test was used to determine the number of bacteria in colony forming units (CFU). Biocarrier sample was collected on day 35 in five locations inside the MBBR, then each sample was diluted up to 107. After the dilution, the bacteria were isolated using the TPC method by taking 0.3 mL from the 10−5, 10−6, and 10−7 dilutions and then placing it in a Petri dish containing nutrient agar (which was already solid) then flattened using L-Glass. Then, the bacterial isolation was incubated for 24 h at a temperature of 30 °C and the next day the bacteria colonies were observed and counted using a colony counter. Next, identification of bacteria groups was carried out by gram staining.

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDX)

The characteristics of the biofilm and its constituent components can be determined using SEM-EDX. Before carrying out SEM-EDX testing, the sample was dried. Then, the sample was oxidized using SEM equipment. The sample was placed and attached using the SEM holder. SEM-EDX mapping testing was carried out using JEOL 6510 series.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

To ensure the validity of the results, each aeration treatment was evaluated across five independent biocarrier sampling locations, which served as biological replicates for the analysis of microbial colony counts. These data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) tests to determine statistically significant differences between treatments. In contrast, the correlation analyses among dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration, biofilm thickness, and TAN removal efficiency were conducted using summary-level data extracted from weekly observations and graphical trends. Due to the absence of daily or replicate-level measurements for these variables, simple linear regression was applied in an exploratory manner to assess general relationships, rather than infer precise statistical causality. This approach enabled a quantitative interpretation of key trends within the nanobubble-enhanced MBBR system, while acknowledging the limitations of data granularity.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Biofilm Growth

Figure 4 illustrates the temporal variation in total ammonia nitrogen (TAN) concentration and dissolved oxygen (DO) levels in the RAS fish tank over the 35-day experimental period. As shown in

Figure 4a, the TAN concentration fluctuated during the experiment, reflecting changes in ammonia generation and nitrification activity within the aquaculture system. The nanobubble-aerated condition generally exhibited lower TAN levels than the coarse-bubble condition, indicating more efficient ammonia oxidation. Meanwhile,

Figure 4b shows that DO concentrations in the fish tank were maintained within the optimal range of 5–8 mg L

−1 for aquaculture operations, with nanobubble aeration providing slightly higher and more stable oxygen levels than coarse-bubble aeration. These results confirm that the influent water supplied to the MBBR represented typical RAS wastewater conditions and that performance differences observed in the reactors were primarily due to aeration characteristics rather than variations in feed water quality.

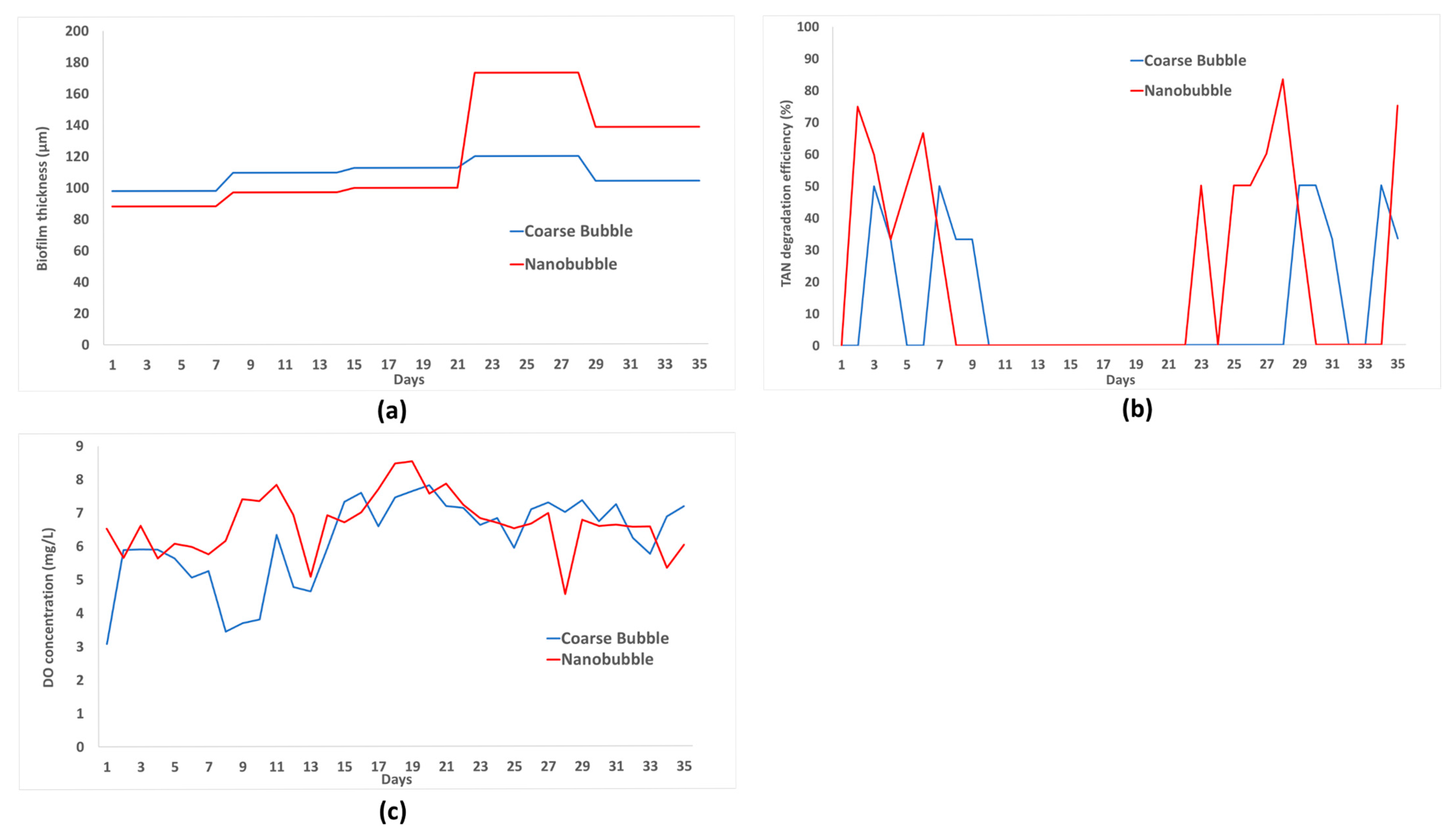

Biofilm thickness, TAN degradation efficiency, and DO concentration in MBBR with nanobubbles and coarse-bubbles aeration during 35 days of the experiment are plotted in the graphs in

Figure 5. In the first week, both systems using nanobubble and coarse-bubble aeration produced good TAN degradation efficiency as can be seen in

Figure 5b. Higher value of TAN degradation efficiency of 66.67% was achieved by nanobubbles compared to coarse bubbles on day six. Meanwhile, using coarse-bubble aeration achieved the higher degradation efficiency of 50% on day seven. This was related to the reversible attachment stage which was the initial phase of biofilm growth, at this stage the bacteria needed more nutrients to attach [

20]. In addition, the nitrification process could occur in the liquid because there were bacteria that were still suspended in the liquid. Coarse bubbles with thickness a of 98 μm in the first week were a result of the higher thickness of the biofilm (

Figure 5a).

In the second and third weeks, there was a decrease in MBBR performance with 0% of TAN degradation efficiency using coarse bubble aeration after day nine. Meanwhile, in nanobubble aeration this performance degradation occurred after day seven. This performance degradation occurred because the bacteria entered a period of starvation during the reversible attachment stage. This stage led to the TAN not being consumed by bacteria [

21]. The decrease in MBBR performance could also be due to the relatively small increase in biofilm thickness, which was 96.88 (week two) μm and 99.75 μm (week three) for nanobubble aeration and 109.38 μm (week two) and 112.5 μm (week three) for coarse bubble aeration, as can be seen in

Figure 5a. At week four, MBBR with nanobubble aeration showed good performance as was indicated by the TAN degradation efficiency reaching 83.33% on day 28. This was due to the biofilm being in the maturation stage with a maximum thickness of 172.88 μm. Meanwhile, MBBR using coarse bubbles had a lower performance with a 0% TAN degradation efficiency, with biofilm thickness increasing to 119.88 μm. In the last week of the experiment (week five), due to the detachment phase, the biofilm thickness reduced to 138.25 μm and led to a reduction in TAN degradation efficiency, reaching only 75% on day 35. Meanwhile, for MBBR with coarse-bubble aeration, there was an increase in performance with degradation efficiency reaching 50% on day 30, with a biofilm thickness of 104 μm.

DO concentration in the first week of the experiment, as can be seen in

Figure 5c, maintained within the range of 5.0–5.9 mg/L. In weeks two and three, the DO concentration in the MBBR exceeded 7 mg/L, but this did not affect the reduction in TAN for nanobubble aeration. In contrast, under coarse-bubble aeration, a decrease in TAN was observed on days eight and nine when the DO concentrations were relatively low, at 3.45 mg/L and 3.70 mg/L, respectively. In weeks four and five, the DO concentration of nanobubble aeration dropped below 7 mg/L, which contributed to an increase in TAN degradation efficiency. Meanwhile, under coarse bubble aeration, efficient TAN degradation occurred at DO concentrations between 6.7 and 7.4 mg/L during week five.

Based on reconstructed weekly data from

Figure 5, a quantitative correlation analysis was performed between biofilm thickness and TAN degradation efficiency under nanobubble aeration. Using four representative time points, the Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated at r ≈ 0.89, indicating a strong positive relationship. This suggests that increased biofilm thickness is closely associated with improved TAN removal performance, particularly during the maturation phase. Although derived from summary data, this analysis supports the hypothesis that nanobubble aeration enhances biofilm functionality through improved oxygen delivery and microbial activity.

The accelerated metabolism under nanobubble aeration may increase biofilm growth and activity, potentially leading to earlier or more frequent detachment events. In our 35-day observation, partial biofilm thinning was noted after Day 30, suggesting the onset of natural detachment. Further long-term monitoring of biofilm thickness and suspended solids is recommended to evaluate whether nanobubbles accelerate shedding cycles.

3.2. TPC and Gram Staining

In this study, five biocarrier sampling locations, center, front-right, front-left, back-right, and back-left, including water from the MBBR and water from the fish tank, were treated as biological replicates under two aeration conditions (nanobubble and coarse bubble). The test was conducted at the final stage of the experiment, on day 35. This design enabled a statistically valid comparison of microbial colony growth in the biofilm using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test. Based on the TPC result in

Table 2, the mean colony counts (CFU/g × 10

7) for nanobubble aeration were 293, 228, 28, 151, and 227 (mean = 185.4), while coarse-bubble aeration yielded 50, 43, 67, 38, and 89 (mean = 57.4). The ANOVA test revealed a statistically significant difference between the two treatments (F = 13.27,

p = 0.0041), and Tukey’s post hoc analysis confirmed that nanobubble and coarse-bubble aeration belonged to distinct statistical groups. These results support the hypothesis that nanobubble technology enhances microbial colonization in biofilm systems, likely due to improved oxygen transfer efficiency and stable microbubble dynamics that facilitate microbial adhesion and proliferation on biocarrier surfaces. Moreover, by treating spatial sampling points as replicates, the analysis accounts for inherent variability within the reactor and strengthens the reliability of the observed treatment effects, reinforcing the conclusion that nanobubble aeration offers a statistically and biologically superior approach to biofilm development.

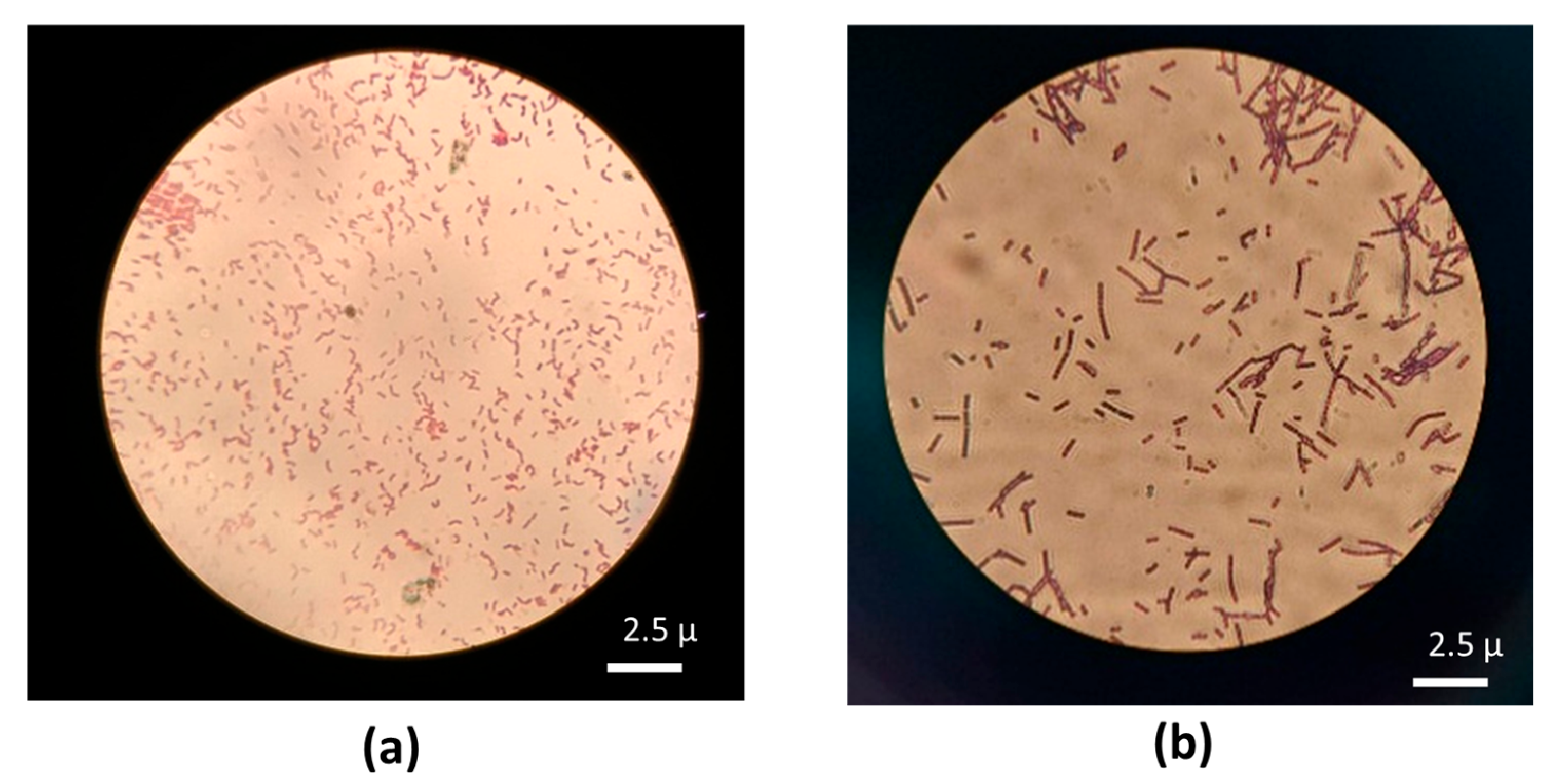

Based on the staining test in

Figure 6, the type of bacteria present in the biofilm media with nanobubble aeration or coarse-bubble aeration, is Gram-negative. This shows that in the biofilm colony there were nitrifying bacteria which are Gram-negative bacteria and were dominated by rod-shaped

Nitrosomonas and

Nitrobacter types [

22]. It can also be seen in

Figure 6 that the bacteria more evenly distributed in the biocarrier with nanobubble aeration compared to the biocarrier with coarse-bubble aeration. Gram staining indicates general bacterial morphology (rod/coccus) and Gram reaction but it cannot identify dominant taxa; molecular methods are required.

Microbial counts were determined using a conventional plate-count technique to estimate viable cell density in the biofilm. Although qPCR or 16S amplicon sequencing would allow detailed taxonomic profiling and relative abundance estimation, these methods were beyond the scope of this pilot-scale engineering study. Future work will incorporate 16S rRNA-based analyses (qPCR and Illumina sequencing) to characterize the community composition of AOB, NOB, and heterotrophs under nanobubble and coarse-bubble aeration. In brackish or marine environments, Nitrospira or Nitrospina species may act as the dominant nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB) instead of Nitrobacter. Future studies employing molecular techniques, such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing or qPCR, will be conducted to confirm the microbial community composition under different salinity conditions.

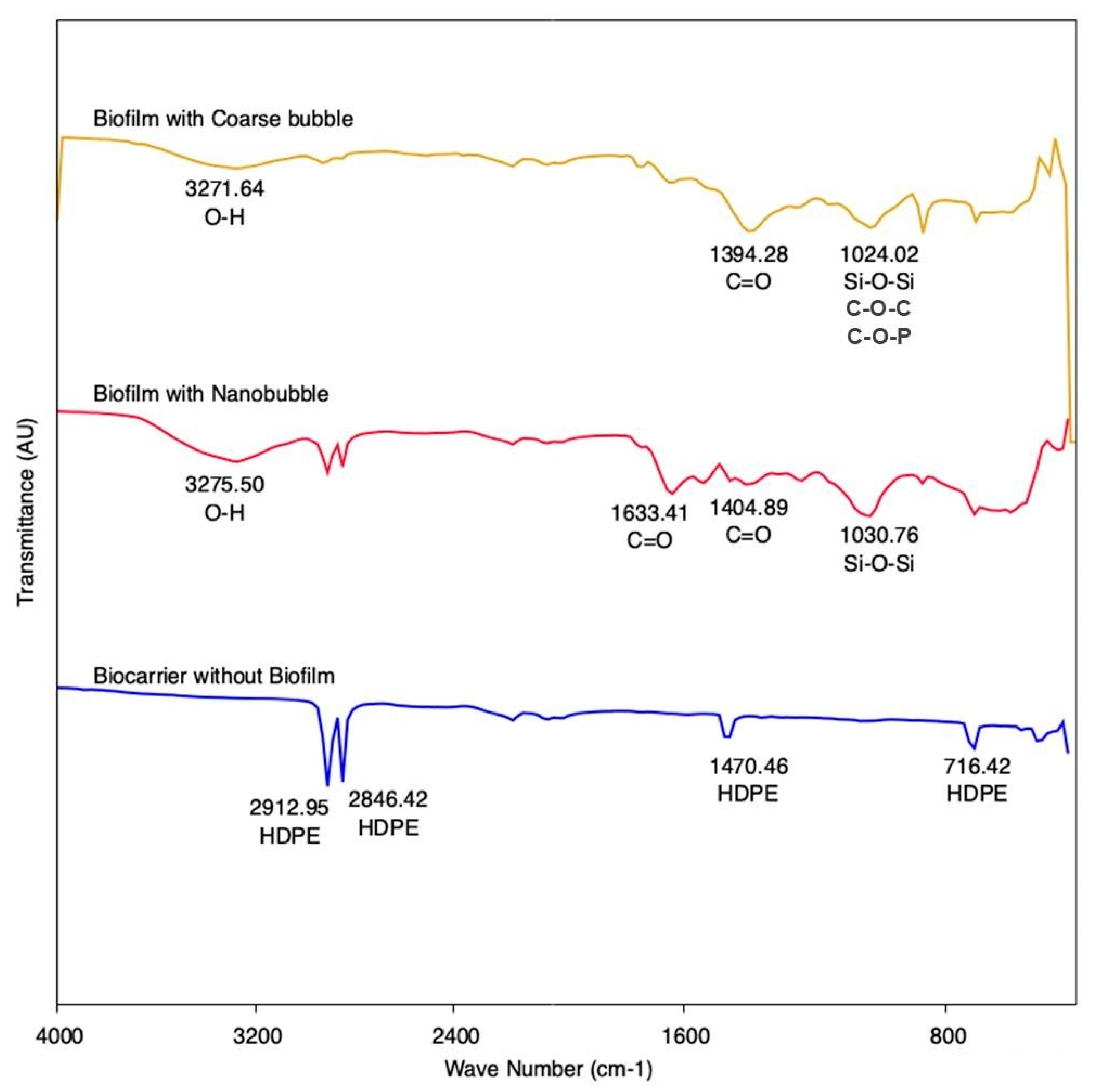

3.3. FTIR Analysis

The highest peak of a biocarrier without a biofilm, as can be seen in

Figure 7, was the wave numbers 2912.95, 2846.42, 1470.46, and 716.42 cm

−1. This peak shows the HDPE, which is a material that was used as a biocarrier. Whereas in the biocarrier with a biofilm, the highest absorption peak at wave number of 3275.50 cm

−1 was produced by nanobubble aeration and 3271.64 cm

−1 was produced by coarse-bubble aeration. This peak is related to O–H stretching vibrations in the hydroxyl group. The highest absorption at wave number 1633.41 cm

−1 in a biocarrier with nanobubble aeration is related to the presence of C=O stretching. Meanwhile, absorption with peak wave numbers of 1404.89 cm

−1 and 1394.28 cm

−1 in nanobubble and coarse-bubble aeration shows C=O symmetric vibration. The peaks of 1030.76 cm

−1 and 1024.02 cm

−1 in nanobubble and coarse-bubble aeration are related to Si–O–Si, C–O–C, and C–O–P asymmetric stretching vibration, this indicates the presence of polysaccharides in the biofilm [

23]. The results of FTIR characterization showed the presence of organic macromolecules from proteins, polysaccharides, and lipids in the biofilm. Media with nanobubble aeration has more functional groups compared to media using coarse-bubble aeration, which is characterized by higher absorption peaks.

The increased biofilm thickness under nanobubble aeration can be attributed to improved oxygen transfer efficiency, uniform nutrient distribution, and reduced shear stress at the biofilm surface. The smaller, stable nanobubbles provided a larger gas–liquid interfacial area and persisted longer in the liquid phase, enhancing mass transfer to microorganisms and supporting deeper aerobic zones. Moreover, nanobubble-induced microstreaming promoted bacterial adhesion and extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) production, leading to the development of a denser and thicker biofilm.

3.4. SEM and EDX Images

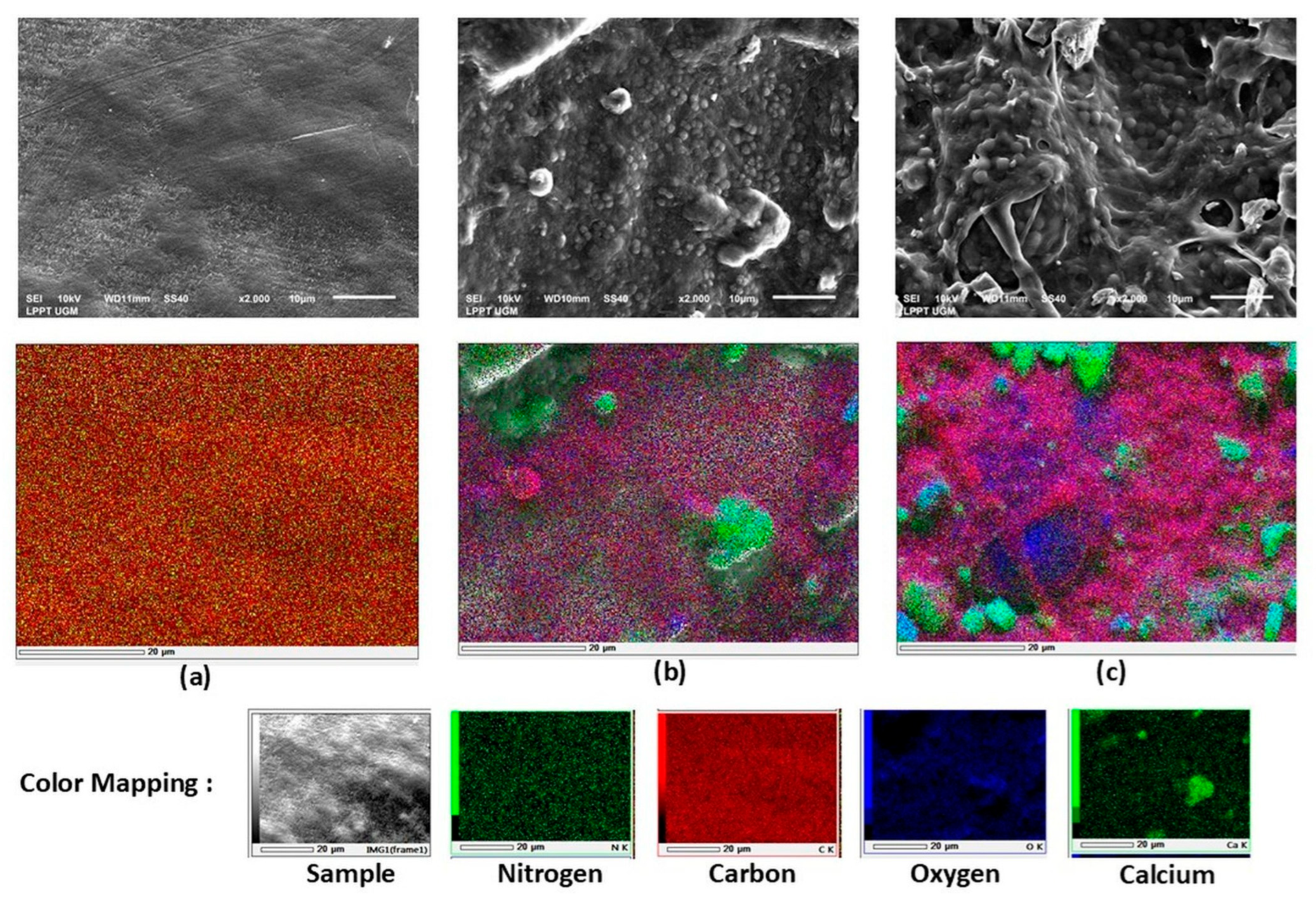

SEM tests were carried out to determine the morphology and component of the biofilm.

Figure 8 is the SEM characteristic of three biocarrier samples, i.e., biocarrier without biofilm, biocarrier with nanobubble aeration, and biocarrier with coarse-bubble aeration.

Figure 8a shows that there are no biofilm or bacterial cells attached to the surface of the biocarrier. Whereas the biocarrier with biofilm using nanobubble aeration (

Figure 8b) shows more homogeneous structure compared to coarse bubbles (

Figure 8c) even though the biofilm structure using coarse-bubble aeration shows larger biomass clusters in the exopolymer matrix. This is in line with the TPC results in

Figure 6b where the distribution of bacteria growing in the biocarrier with nanobubble aeration is higher even compared to the coarse bubble. The evenly distributed biofilm growth is caused by better oxygen transfer in nanobubble aeration compared to coarse bubbles. In addition, the distribution of nutrients into the biofilm with nanobubble aeration was better than with coarse-bubble aeration, this was shown by the good performance of the biofilm in degrading TAN in the fourth and fifth weeks.

The EDX analysis (

Figure 6) qualitatively illustrates the distribution of key elements (C, O, N, and Ca) in the biofilm samples under nanobubble and coarse-bubble aeration. Elemental mapping indicates that biofilms developed under nanobubble aeration contained a higher proportion of carbon- and nitrogen-rich regions, suggesting increased microbial and organic matter accumulation, whereas the coarse-bubble biofilm showed a relatively higher calcium signal, indicating more inorganic deposition. The mapping results of the biocarrier without biofilm in

Figure 6a show the presence of carbon (marked in red) and nitrogen (marked in green). This is related to the material which was used as a biocarrier (HDPE). Whereas on the surface of the biocarrier with nanobubble and coarse bubble aeration, there was calcium, carbon and oxygen compounds which are marked with green, red and blue in

Figure 8b,c. In biofilms, calcium is a component of bacteria which has an important role in cell structure repairment, nutrient transport and cell differentiation process [

24]. Although carbon is a nutrient needed for the growth of bacteria in biofilms, carbon levels in the biofilm can influence the architecture and metabolic activity of the biofilm [

25]. Meanwhile, oxygen is needed for the bacterial respiration process in the biofilm. The oxygen transfer in water consists of three stages; in the first stage oxygen is transferred to the surface of the liquid film. Thereafter, oxygen enters the water body through the air–water interface, causing a diffusion process. Then, oxygen in the form of DO moves in the water body through the convection process [

12]. The process of dissolving gas into water goes through the gas bulk, gas film, liquid film, and liquid bulk stages. Then, the DO in the water body is transferred to the solid phase (biofilm) where the nitrification reaction occurs in the cells [

26].

The distribution of calcium, carbon, and oxygen is more even in

Figure 8b compared to

Figure 8c. While there are several gaps in the biofilm structure that formed on the biocarrier surface with coarse bubble aeration, the colonies were not as many as in nanobubble aeration. This proves that oxygen in nanobubble aeration can be transferred into the biofilm layer better than coarse bubbles. The oxygen transfer is influenced by nanobubble size. The diameter of the nanobubble is much smaller compared to the coarse bubble, resulting in a larger surface area which increases the transfer of oxygen from the bubble to the biofilm layer [

27,

28]. The distribution of oxygen influences the biofilm growth on the biocarrier and aligns with the higher TAN degradation efficiency of nanobubble aeration compared to coarse-bubble aeration.

Nanobubbles enhance microbial activity and biofilm development through several interrelated mechanisms supported by previous studies [

13,

29]. Their ultrafine size and large interfacial area significantly increase oxygen mass transfer efficiency, facilitating deeper oxygen penetration into the biofilm and sustaining aerobic metabolism across different biofilm layers. The generation and collapse of nanobubbles induced localized microstreaming and gentle turbulence, which promotes more uniform bacterial dispersion and nutrient distribution within the biofilm matrix, resulting in improved structural stability and higher microbial activity. Furthermore, nanobubbles reduce shear stress compared with coarse bubbles, thereby minimizing biofilm scouring and allowing the formation of a thicker, more metabolically active biofilm. Collectively, these mechanisms explain the observed enhancement in biofilm growth, ammonia oxidation, and overall nitrogen removal performance under nanobubble aeration.

Moreover, the nanobubble aeration system demonstrated an energy efficiency improvement of approximately 7.47% compared with the coarse-bubble system, based on the measured oxygen transfer per unit power input. Specifically, the coarse-bubble aeration required 4.048 W to achieve a 1 mg L−1 increase in dissolved oxygen (DO), whereas the nanobubble aeration achieved the same DO increase with only 3.75 W. For scale-up applications, this improvement indicates that nanobubble diffusers can replace conventional coarse aeration grids in modular MBBR systems to enhance oxygen transfer while slightly reducing energy consumption. Although the energy savings at pilot scale are modest, the combined effects of improved oxygen utilization and enhanced biofilm performance suggest potential for greater operational efficiency in full-scale recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) under similar hydraulic and loading conditions.

4. Conclusions

The pilot-scale RAS utilizing MBBR with nanobubble aeration was established to lower total ammonia nitrogen (TAN) by boosting biofilm activity. Coarse bubble aeration served as a reference treatment. A 35-day study was carried out to assess biofilm formation and its effect on TAN degradation efficiency. SEM–EDX analysis indicated structural voids in the biofilm developed under coarse bubble aeration, along with a reduced number of microbial colonies in comparison to those treated with nanobubbles. These findings align with the increased TAN degradation efficiency attained through nanobubble aeration (83.33%) compared to coarse bubble aeration (50%). The peak biofilm thickness of 172.88 µm and the greatest colony count of 293 × 107 CFU under nanobubble circumstances reinforce the idea that better distribution of bacteria, nutrients, and oxygen aids with improved biofilm efficacy and TAN elimination. If operated for a second cycle, the nanobubble-aerated reactor is expected to maintain higher stability due to the formation of a mature biofilm with greater microbial density and activity. However, periodic sloughing or detachment may occur as part of the natural biofilm life cycle. Future work will include multi-cycle operations to evaluate long-term stability, recovery rate after sloughing, and resilience against load fluctuations.

The pilot-scale results demonstrate that nanobubble aeration significantly enhances biofilm formation and ammonia removal efficiency compared with conventional coarse-bubble aeration. These improvements highlight the strong potential of nanobubble technology for full-scale implementation in both recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) and municipal MBBR operations. The system can be retrofitted into existing aeration setups with minimal modification and showed an energy efficiency improvement of approximately 7.47% per unit of dissolved oxygen transfer. Further large-scale and long-term studies are recommended to optimize diffuser configuration, evaluate operational stability, and conduct comprehensive techno-economic and energy performance assessments prior to industrial deployment.

Although this research highlights the considerable promise of nanobubble aeration in improving biofilm formation and TAN reduction in MBBR systems, certain limitations must be recognized. Molecular techniques for microbial community profiling and evaluations of long-term system stability were not considered. Moreover, the correlation analyses involving biofilm thickness, TAN degradation efficiency, and DO concentration relied on summary-level data gathered from weekly observations, which constrains the robustness of statistical inference. Future studies should include high-resolution time-series data, metagenomic techniques, and reaction kinetics modeling to enhance the comprehension of nanobubble mechanisms within biofilm systems. Future studies should also include the measurement of oxygen microprofiles within the biofilm and applying 16S rRNA sequencing to identify nitrifying populations. Additionally, a longer-term operation (multiple cycles) is needed to assess stability and biofilm detachment dynamics. Moreover, studies on large-scale industrial implementations and cost–benefit analyses will be crucial for facilitating wider adoption and practical integration of this technology.