1. Introduction

Mapping the fluctuations of mountain glaciers provides important information about long-term regional atmospheric and hydrological variability, as well as the management water resources and cryospheric hazards in glaciated mountain catchments [

1,

2,

3]. Since the end of the Little Ice Age (LIA), a period generally spanning from the 14th to the mid-19th century, mountain glaciers worldwide have experienced pronounced retreat and thinning [

4,

5,

6]. These changes have been well documented in many mountain regions. For example, the European Alps [

7,

8], the Andes [

9], Alaska [

10], Scandinavia [

11], the Himalaya [

6], Central Asia [

12,

13], and the Caucasus, where early cartographic surveys, photographs, and, more recently, satellite observations provide multi-century records of glacier fluctuations [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

The latest phase of the LIA maximum in the Greater Caucasus is typically assigned to the late 18th or early 19th century, with the termination often placed around the 1820s. This date is accepted in individual glacier reconstructions based on cosmogenic dating (

10Be), dendrochronology, and lichenometry and provides a consistent reference point from which to calculate subsequent glacier change rates [

16]. Consequently, in this study we adopt 1820 as the approximate termination of the LIA in the Greater Caucasus and as the baseline for quantifying post-LIA evolution of Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier. This assumption allows direct comparison with previous Caucasus-wide analyses and ensures methodological consistency across multi-temporal reconstructions.

Alongside glacier retreat, the formation and expansion of proglacial lakes have emerged as a critical phenomenon in deglaciating mountain regions [

19,

20]. Proglacial lakes form in overdeepened beds and/or behind moraine dams left by retreating ice, with their growth rates determined by the pace of glacier retreat [

21,

22,

23]. These lakes are increasingly significant for several reasons: (i) they act as integrators of catchment hydrology, storing meltwater and regulating downstream discharge [

24], and (ii) they present acute hazards in the form of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), which can release sudden, destructive torrents downstream [

25,

26]. GLOFs represent a significant hazard in many glaciated mountain ranges that are experiencing glacier shrinkage [

27,

28,

29]. The Caucasus has already experienced several destructive GLOF events in recent years [

30,

31,

32,

33]. These events highlight the urgency of systematic monitoring of proglacial lakes in the region and the need for integrated hazard assessments.

The Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier system (43°4′26″ N 42°57′49″ E), located in the Zemo (Upper) Svaneti region on the southern slope of the Greater Caucasus, is one of the largest glaciers in Georgia and historically ranked second in size after Lekhziri Glacier (43°9′21″ N 42°45′54″ E) [

34]. Fed by multiple tributaries descending from Mt. Tetnuldi (4858 m a.s.l.), Mt. Lalveri (4350 m a.s.l.), Mt. Gistola (4860 m a.s.l.), and Mt. Tikhtengeni (4617 m a.s.l.), Tsaneri–Nageba was (before recent fragmentation) a massive compound valley glacier with a continuous tongue extending deep into the Mulkhura River valley. Over the past few decades, the fragmentation of the Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier has led to changes in its proglacial environment and the formation of a proglacial lake. While the lake is currently modest in size, its continued growth in response to glacier thinning and retreat could amplify downstream risks.

Beyond its glacio-geomorphological significance, a stronger case for detailed investigation of the Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier system lies in its socioeconomic and cultural context. Numerous villages are situated downstream, accompanied by dozens of guesthouses that accommodate thousands of tourists every year visiting the surrounding natural and cultural landmarks. This highlights the significant risk that glacier-related hazards can pose to human settlements and heritage sites.

The aims of this study are, therefore, as follows: (i) to reconstruct the evolution of the Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier from its LIA maximum (~1820) to the present day (2025) using a combination of geomorphological evidence, historical cartography, and high-resolution satellite imagery; and (ii) to document the formation, geometry, and volume of the Tsaneri proglacial lake using Uncrewed Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-based mapping and sonar measurements.

By integrating long-term glacier change with contemporary lake dynamics, we seek to highlight the interconnected processes shaping the headwaters of the Mulkhura–Enguri river system. This research contributes not only to regional glaciological knowledge but also to practical risk assessment, providing a basis for monitoring and modeling potential future GLOF scenarios. Ultimately, the Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier system offers a valuable case study of post-LIA deglaciation in the Greater Caucasus and underscores the need for sustained interdisciplinary monitoring to safeguard both local communities and downstream infrastructure.

2. Study Area

The Greater Caucasus is a prominent mountain system extending about 1200 km between the Black and Caspian seas, forming a natural barrier between Eastern Europe and Western Asia (

Figure 1). The range reaches its maximum width of 150–180 km in its central section, between Mt. Elbrus (5642 m a.s.l.) and Mt. Kazbegi (5047 m a.s.l.). The southern slopes descend steeply into the Enguri and Rioni river catchments, while the northern slopes drain into the Terek (Tergi) and Kuban river basins. Elevations in the Greater Caucasus vary from 400 to 600 m at valley floors to >5000 m a.s.l. at summits, creating sharp vertical gradients in topography, climate, and vegetation. Hypsometrically, much of the Greater Caucasus lies above 2000 m a.s.l., with extensive alpine belts, cirques, and glacially carved troughs [

35].

The Greater Caucasus play a critical role in regulating regional hydrology, capturing abundant atmospheric moisture and redistributing it to major river systems [

36]. The Mulkhura River, a left tributary of the Enguri, originates in the central Caucasus and is fed by meltwater from several large glaciers, including Tsaneri and Nageba (

Figure 1). The river flows south-westward through the high-mountain district of Zemo Svaneti region, before merging with the Enguri River, which eventually drains into the Black Sea.

The Greater Caucasus represents a complex orogenic system formed during the Alpine–Himalayan orogeny. Its lithological diversity reflects multiple phases of tectonic accretion, subduction, and collision [

37]. The central part of the range, where Tsaneri Glacier is located, consists largely of metamorphic and igneous rocks, including schists, gneisses, amphibolites, and granitoid intrusions. These units are interspersed with sedimentary successions, such as Jurassic sandstones and limestones, which were subsequently deformed and uplifted during Cenozoic tectonic activity [

38].

The geology exerts a strong influence on glaciation and landscape evolution. Resistant crystalline rocks form steep cirque headwalls and arêtes, providing suitable topography for glacier accumulation zones. In contrast, weaker sedimentary sequences are prone to weathering and slope instability, enhancing paraglacial hazards. Moraines and till deposits of Late Pleistocene and Holocene age are widespread in valley bottoms and serve as archives of former glacier extents [

39,

40]. In the Tsaneri–Nageba catchment, lateral–terminal moraines delineate the LIA maximum and subsequent retreat stages. The tectonically active setting also contributes to seismic hazards [

41], which may interact with glacial and paraglacial processes.

The Greater Caucasus lies at the intersection of several climatic regimes, with strong spatial variability controlled by elevation, aspect, and proximity to moisture sources. The western sector is strongly influenced by humid subtropical air masses from the Black Sea, while the eastern sector experiences more continental conditions [

42]. In the central Caucasus, where the Tsaneri Glacier is situated, annual precipitation can exceed 1100 mm (1961–2024) according to the Mestia weather station (located at 1440 m a.s.l.,

Figure 1).

The Greater Caucasus hosts the largest glaciated area in Europe outside the Alps, with ~2200 glaciers covering ~1060 km

2 in 2020 [

43]. Glacier types range from small (<0.5 km

2) cirque to extensive (>10 km

2) valley and compound valley glaciers. Since the end of the LIA (1820s), the area of small glaciers in the Greater Caucasus has decreased by −51% with the regional equilibrium-line altitude (ELA) rising from ~3245 to ~3425 m a.s.l., in line with regional warming of 1.1 °C over that same period [

16]. In 2020, about 10% of the total glacierized area in the Greater Caucasus was covered by supraglacial debris [

44].

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Glacier Mapping

The Mulkhura River valley preserves LIA moraines of the Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier. The outermost latero-terminal moraines, with sharp crests and well-preserved morphologies, are interpreted as representing the glacier’s approximate extent around 1820. These moraines were mapped in the field and confirmed with high-resolution Google Earth and Planet Labs satellite imagery to ensure consistent delineation of glacier margins.

The first cartographic record of Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier is provided by large-scale (1:42,000) Russian military topographic maps from 1889 (

Table 1,

Figure 2). These maps, although compiled for strategic purposes, offer remarkably accurate depictions of glacier tongues [

34], particularly for large valley glaciers such as Tsaneri–Nageba. We digitized glacier boundaries from a georeferenced scan of one of these maps, applying corrections based on identifiable topographic features. For 1933, we adopted glacier outlines from Rutkovskaya [

45], who provided terminus elevations, hand-drawn maps and detailed descriptions of the Upper Svaneti glaciers.

Soviet 1:50,000 scale topographic maps from the 1960s served as the next key reference point, providing a regionally consistent snapshot of glacier extent. These maps have been widely used for a previous regional glacier inventory [

46]. For subsequent decades, we used multispectral satellite imagery, including Landsat 5 TM (1986), Landsat 7 ETM+ (2000), and Landsat 8 OLI/TIRS (2014) images; these were acquired for late summer under cloud-free conditions, and enabled manual mapping of glacier outlines (

https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov; accessed on 18 August 2025). For the most recent period (2025), we used high-resolution (3 m) PlanetScope imagery (

https://www.planet.com/explorer/; accessed on 10 September 2025) and Google Earth Pro orthophotos (

https://earth.google.com/web/; accessed on 23 September 2025).

Hypsometric characteristics were derived using the 12.5 m ALOS PALSAR DEM (2007) (

https://vertex.daac.asf.alaska.edu; accessed on 16 August 2025) [

47]). Glacier outlines from each epoch were intersected with DEM elevations to calculate terminus positions. Glacier centrelines were established using flowline analysis, and terminus retreat distances were measured along these flowlines [

48].

To assess mapping uncertainty, we adopted the buffer method, which estimates error based on image resolution, map scale, and interpreter subjectivity. Following previous studies [

34,

43,

46], uncertainties were propagated as ±2.1–5.5% of mapped area, with larger errors assigned to early cartographic sources and smaller errors to modern satellite images. These estimates are summarized in

Table 2. Ablation areas and tongues were generally straightforward to delineate, while the main challenge was mapping accumulation areas in earlier epochs (1820–1933), where limited cartographic detail complicated interpretations. To overcome this, we combined geomorphological field observations, historical descriptions, local knowledge, and modern high-resolution imagery to constrain accumulation basin boundaries.

3.2. Drone Survey and Proglacial Lake Mapping

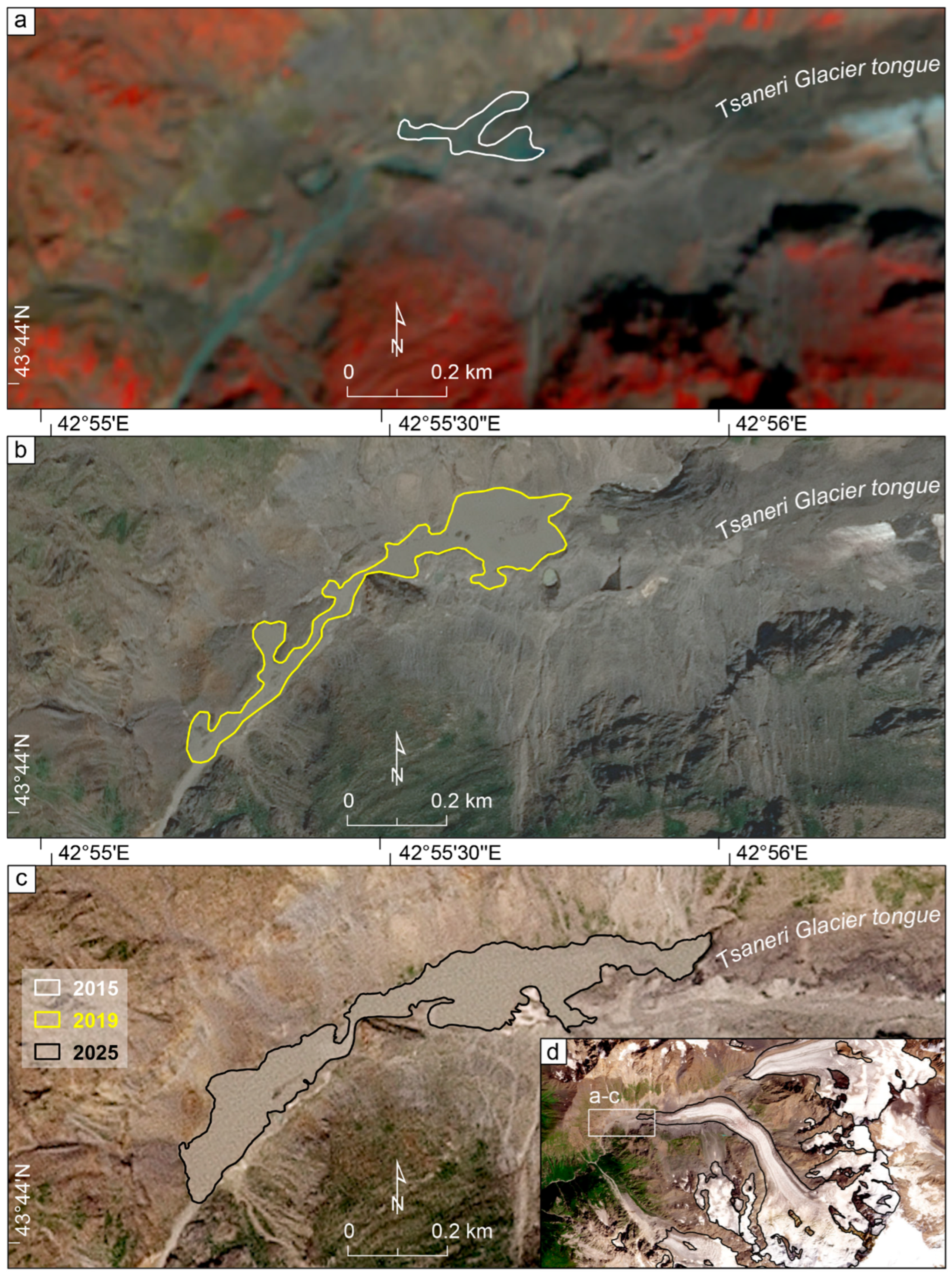

Proglacial lake development was reconstructed using both remote sensing and field surveys. A Sentinel-2 image from 3 September 2015 provides the earliest clear evidence of proglacial lake initiation in front of Tsaneri. To constrain its subsequent surface area evolution, we examined a cloud-free SPOT6 scene from the 30 July 2019, and a Planet image from the 19 August 2025.

An uncrewed aerial survey of the glacier tongue and proglacial lake was conducted using a DJI Mavic 3 Pro drone (

Figure 3). The flights were performed at an altitude of 250 m above ground level, resulting in the acquisition of 337 overlapping images. For georeferencing, 12 ground control points (GCPs) were established and measured with a Stonex 9 III differential GPS (DGPS), providing centimeter-level positional accuracy. The total survey area covered approximately 300 ha. Image processing was carried out in Agisoft Metashape Professional, following a standard photogrammetric workflow that included image alignment, dense point cloud generation, mesh construction, and raster interpolation. This procedure produced a georeferenced orthophoto mosaic with a spatial resolution of 5 cm and a digital elevation model (DEM) with a resolution of 20 cm. The resulting products were subsequently integrated into ArcMap 10.8.2 for spatial analysis and cartographic visualization. These datasets provided the basis for detailed mapping of lake margins and detection of subtle geomorphic features such as incipient landslides or seepage channels., i.e., Lake surface area for 2025 was measured directly from these orthophotos while the Planet image from 2025 served as a supplement.

3.3. Bathymetric Survey and Data Processing

A bathymetric survey of the Tsaneri Lake was conducted using a Garmin Echomap UHD 73sv Fish Finder equipped with a GT54UHD-TM transducer (

Figure 3). This system operates with high-resolution sonar technology, enabling the acquisition of precise depth measurements along predefined transects across the lake surface. Prior to data collection, the device was calibrated, and the survey design was planned to ensure full spatial coverage of the basin. The scanning was performed systematically, with the sonar continuously recording depth profiles and associated positional information during navigation across the lake.

The raw sonar records obtained from the device were then exported in a compatible digital format for further processing. These data were subsequently imported into the ReedMaster software 2.0, which provided tools for initial cleaning and refinement. Within ReedMaster, noise filtering and correction procedures were applied to remove potential artifacts and inconsistencies caused by signal scattering, vegetation interference, or motion-related errors. As a result, a dataset of corrected and reliable depth measurements was generated, suitable for integration into a GIS platform.

Following the preprocessing stage, the cleaned dataset was transferred to ArcMap 10.8.2 for advanced spatial analysis. The sonar-derived depth points were georeferenced and interpolated using established spatial interpolation techniques (e.g., Inverse Distance Weighting, IDW, or Kriging), which allowed for the generation of a continuous bathymetric surface model. The resulting raster provided a detailed representation of the underwater topography of the Tsaneri Lake, accurately reflecting depth variations across the basin.

The volume estimation was carried out using the Surface Volume tool in ArcMap’s 3D Analyst extension. The interpolated bathymetric raster served as the input surface, while the lake’s shoreline polygon defined the reference plane representing the water surface elevation. The tool computed the total submerged volume by integrating all depth values below the reference level, producing the total water volume in cubic meters. This GIS-based volumetric calculation enabled an accurate assessment of the lake’s storage capacity and provided a foundation for further hydrological modeling. To ensure accuracy, the spatial resolution of the raster and the interpolation parameters were carefully adjusted to minimize potential errors related to point density, irregular morphology, and data precision.

3.4. Climate Data

To assess the climatic drivers of glacier change, we analyzed long-term meteorological observations from the Mestia weather station (1440 m a.s.l.), the only continuous station in the region, operating since 1936. We extracted mean monthly and annual temperature and precipitation series. We focused on mean summer (May–September) temperatures, which strongly control glacier ablation, and total winter (November–March) precipitation, which largely determines annual accumulation [

49]. The complete methodological workflow of this study is presented in

Figure 4.

4. Results

4.1. Area Decrease Since the LIA

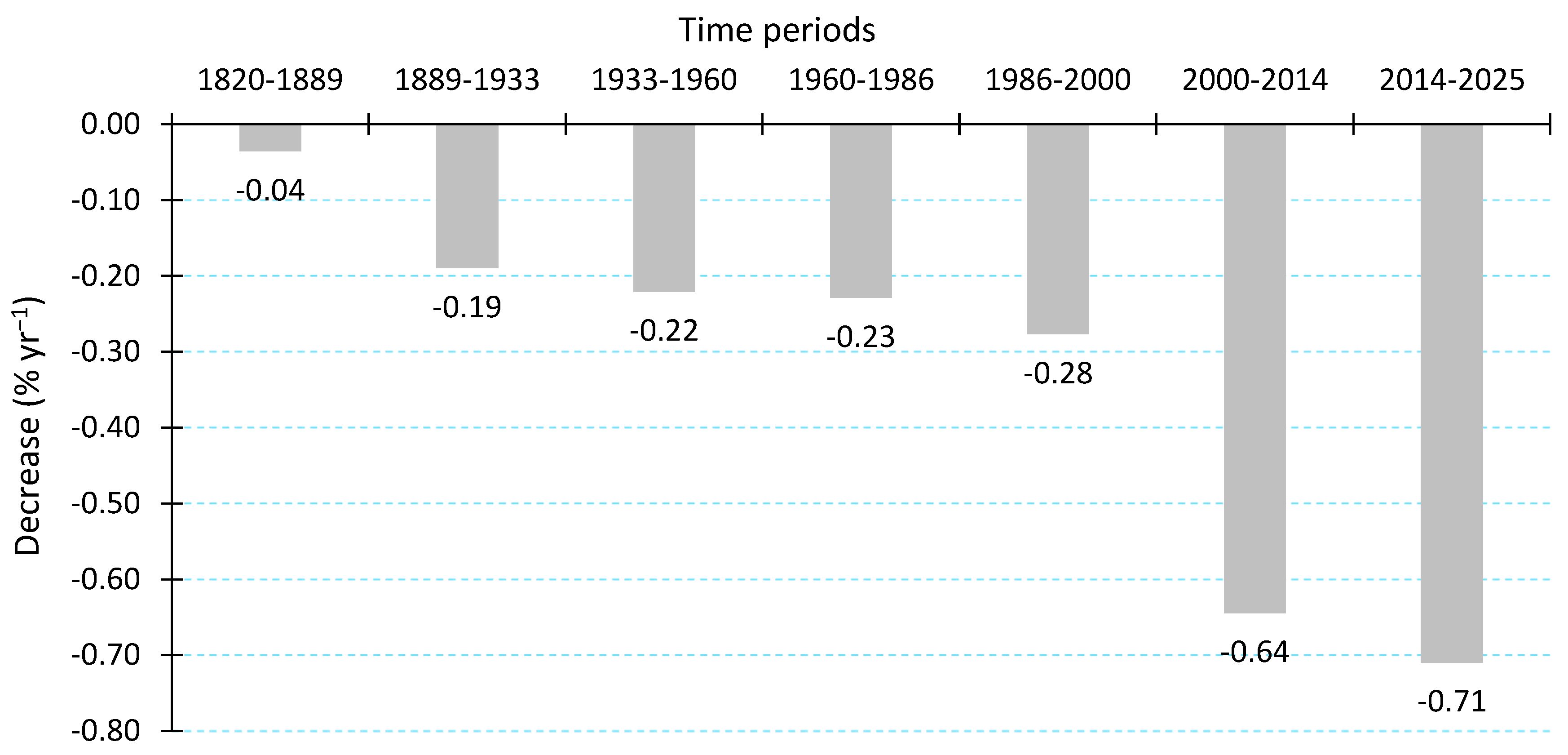

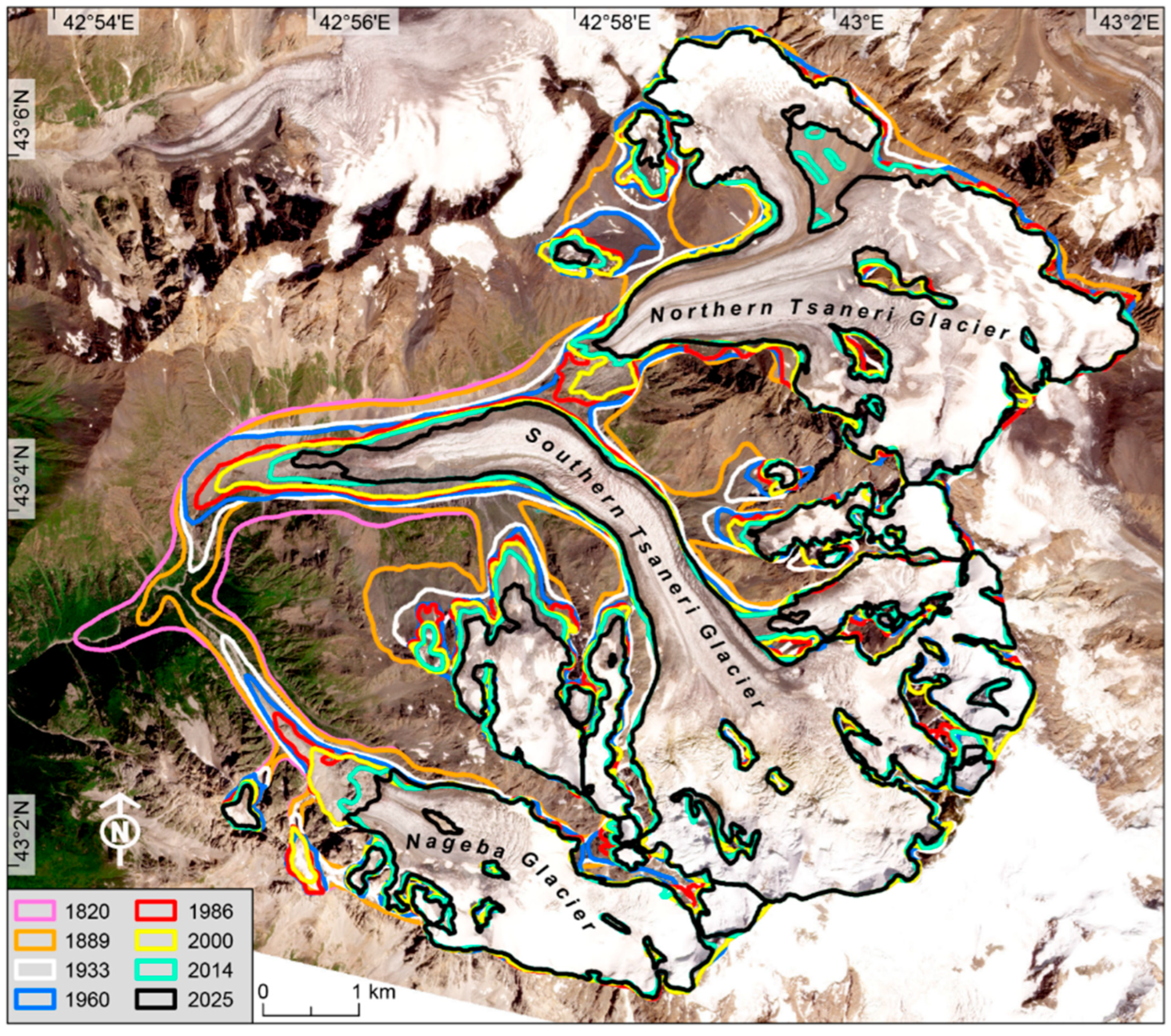

The Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier has experienced continuous shrinkage since its LIA maximum around 1820, when its area was found to be 47.99 ± 2.63 km

2 (

Table 2). By 1889, the glacier area had decreased slightly to 46.80 ± 2.52 km

2, representing a modest reduction of ~1.19 km

2 (−2.48%; −0.017 km

2 yr

−1). Between 1889 and 1933, Tsaneri–Nageba lost an additional ~3.91 km

2 (−8.35%), marking an acceleration in shrinkage to −0.089 km

2 yr

−1. During this period, the Nageba Glacier separated from the main part of the Tsaneri Glacier. The period 1933−1960 recorded a further loss of ~2.56 km

2 (−5.97%; −0.095 km

2 yr

−1), while from 1960 to 1986, another ~2.40 km

2 was lost (−5.95%), though this represents a slight reduction in the rate of ice loss to −0.092 km

2 yr

−1. By 1985–1986, Tsaneri had divided into two parts—North and South Tsaneri. Decrease rates increased further in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Between 1986 and 2000, the glacier lost ~1.47 km

2 (−3.88%; −0.105 km

2 yr

−1). The steepest proportional losses occurred in the 21st century: the loss from 2000 to 2014 was ~3.29 km

2 (−9.02%; −0.235 km

2 yr

−1), while another ~2.59 km

2 was lost between 2014 and 2025 (−7.81%; −0.235 km

2 yr

−1). In total, the Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier system lost ~17.41 km

2 of ice cover between 1820 and 2025, equivalent to −43.46% of its LIA area, with an average decrease rate of −0.21% yr

−1 (

Table 3,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

4.2. Terminus Retreat and Elevation Changes

The glacier termini of both Tsaneri and Nageba show strong cumulative retreat since 1820 (

Table 4). Between 1820 and 1889, when the glaciers shared a joint tongue, the system retreated ~700 m (−10.1 m yr

−1). After 1889, the glaciers separated, and retreat rates diverged. From 1889 to 1933, Tsaneri retreated by ~806 m (−18.3 m yr

−1), while Nageba receded even faster, at ~1240 m (−28.2 m yr

−1). Both glaciers maintained high retreat rates through the mid-20th century: Tsaneri lost ~526 m between 1933 and 1960 (−19.5 m yr

−1), while Nageba retreated ~485 m (−18 m yr

−1).

During 1960–1986, Tsaneri’s rate of recession slowed to –6.6 m yr⁻¹, but Nageba continued rapidly at –19.5 m yr⁻¹. In the period 1986–2000, the rates of recession for both glaciers accelerated again: Tsaneri retreated ~283 m (–20.2 m yr⁻¹) and Nageba ~532 m (–38 m yr⁻¹). The early 21st century recorded the most dramatic retreat rates, particularly between 2000 and 2014 (Tsaneri ~590 m, –42.1 m yr⁻¹; Nageba ~496 m, –35.4 m yr⁻¹). The period 2014–2025 exhibited extreme retreat at Tsaneri, with ~827 m lost (–75.2 m yr⁻¹), while Nageba shortened by ~360 m (–32.7 m yr⁻¹). Over the full 1820–2025 record, Tsaneri retreated by ~3904 m (–19 m yr⁻¹), while Nageba receded ~4320 m (–21.1 m yr⁻¹).

Both glacier termini have retreated to higher elevations (

Table 5). The terminus of Tsaneri rose from ~1976 m a.s.l. in 1820 to ~2440 m a.s.l. in 2025, a total vertical shift of +464 m. The terminus of Nageba rose even more dramatically, from ~1976 m a.s.l. to ~2946 m a.s.l. (+970 m). Most of this up-valley shift occurred in the 20

th and early 21

st centuries.

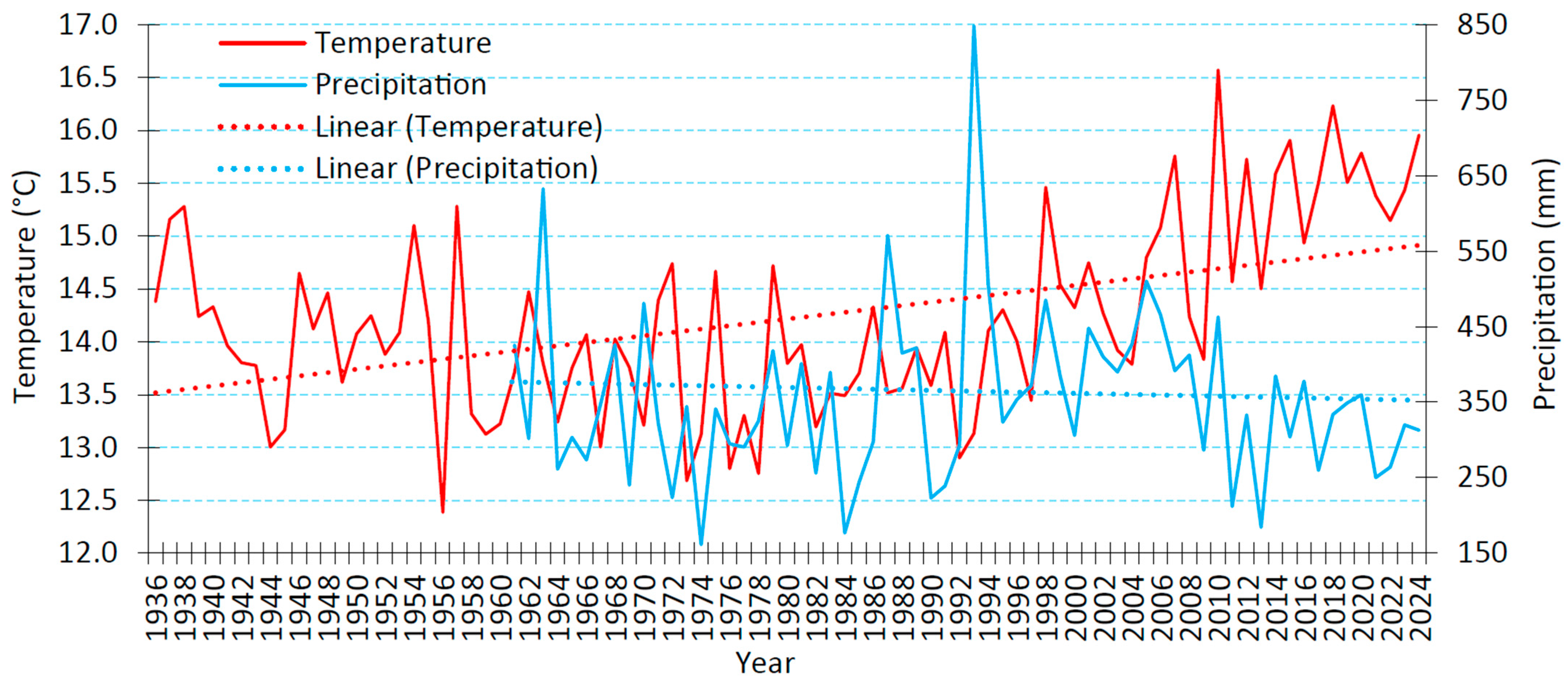

4.3. Climate Change

Long-term records from the Mestia weather station reveal an overall increase in air temperature and decrease in precipitation over the study period, albeit with large interannual variations in both datasets (

Figure 7). Mean summer (May–September) temperatures increased markedly between 1936 and 2024, with a sharp rise after 1990. Simultaneously, winter (November–March) precipitation decreased after 1961, reducing snow accumulation and possible shifting precipitation phase toward rainfall at mid-elevations.

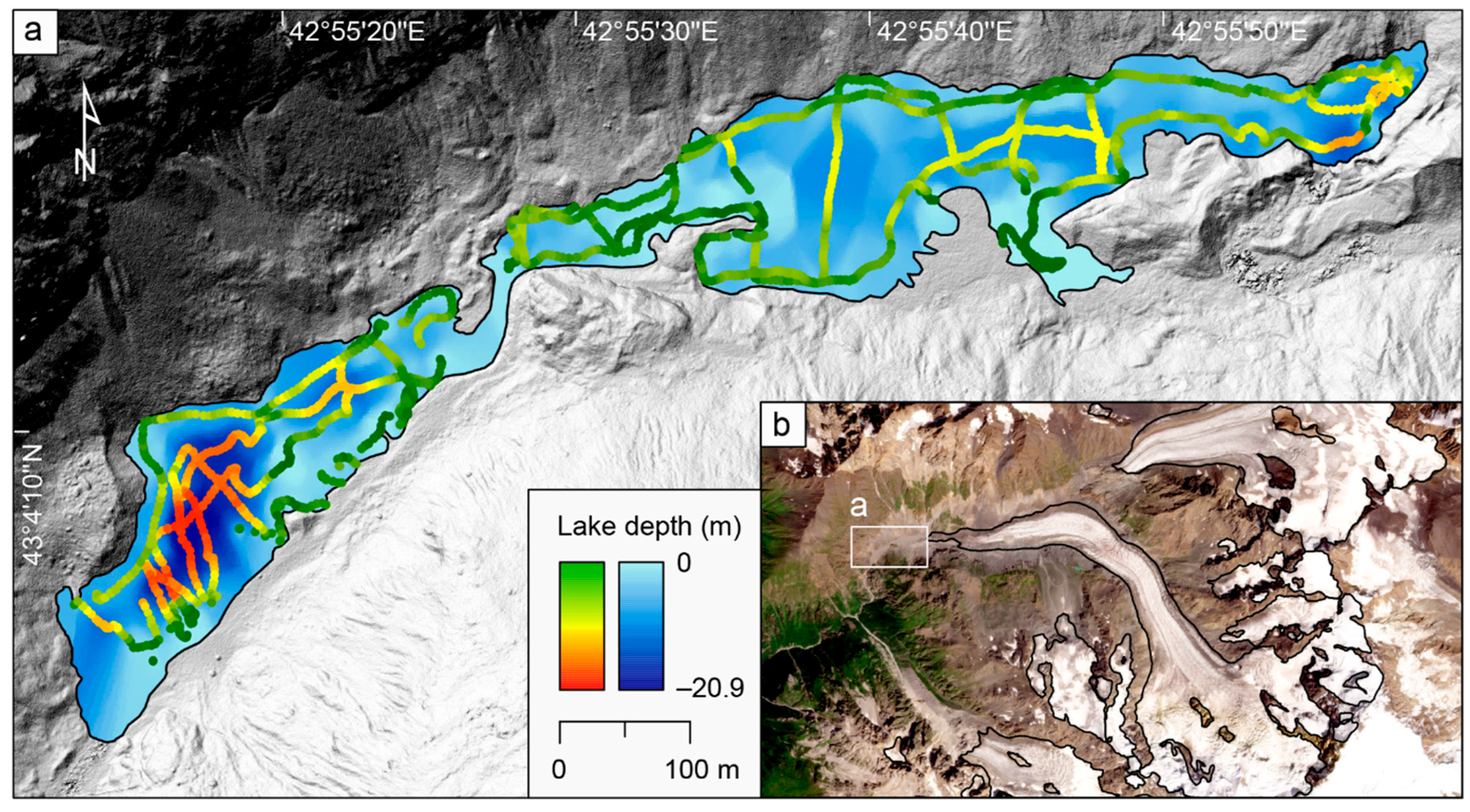

4.4. Proglacial Lake Formation

A Sentinel-2 image from 3 September 2015 shows that a proglacial lake had begun to form at the terminus of the Southern Tsaneri Glacier with an area of ~14,366 m

2. By 30th July 2019 a SPOT6 image shows that the lake had increased in area to ~62,420 m

2. UAV orthophotos from a survey in July 2025 revealed a lake surface area of ~106,945 m

2 (

Figure 8). Bathymetric profiling indicated an average depth of −5.9 m and a maximum depth of −20.9 m, with a total calculated volume of ~639,800 m

3. The lake occupies an overdeepened basin immediately in front of main ice stream of the Southern Tsaneri, bounded by unconsolidated moraines and steep scree/till walls.

5. Discussion

5.1. Driving Factors for Glacier Decrease in a Regional Context

During the LIA, Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier formed a compound valley system incorporating multiple tributaries. Since the LIA, glacier area has decreased by ~17.41 km

2 (

Table 3), with terminus retreat of ~3.9 km for Tsaneri, and ~4.3 km for Nageba (

Table 4). The glacier has thinned and fragmented, with tributaries detaching and compound valley morphology giving way to separate valley and cirque glaciers. This fragmentation has amplified sensitivity to warming, as smaller glaciers have higher perimeter-to-area ratios and are more vulnerable to ablation [

50,

51,

52,

53]. Despite its reduction, Northern and Southern Tsaneri remains among the largest glaciers of Georgia, with a significant role in regulating the hydrology of the Mulkhura–Enguri river basin (see

Section 5.3).

The decrease in Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier since the LIA reflects broader Caucasus-wide patterns of deglaciation, which accelerated particularly in the late 20th and early 21st centuries [

43,

46,

49,

54]. Comparative inventories indicate that total glacierized area in the Greater Caucasus declined by ~50% since the early 19th century, with the steepest losses occurring after 2000 [

16].

Analysis of climate data show that a key driver of accelerated area decrease has been the sharp increase in summer temperatures since the 1990s (

Figure 7). Longer ablation seasons [

55,

56] and more frequent heatwaves [

57,

58] have contributed to higher ablation rates. The warming trend is likely to be driven primarily by large-scale climatic forcing (i.e., global or hemispheric warming) [

3] rather than local factors.

In addition, the decline in winter precipitation (e.g., snowfall), has limited accumulation, reducing the glacier’s ability to replenish ice mass [

59], which directly affect the mass balance of glaciers. The observed decrease in precipitation is largely attributed to changes in atmospheric circulation patterns (e.g., moisture source trajectories, high-pressure blocking, seasonal shifts) as well as the influence of local topography and terrain effects [

60].

These climatic changes provide crucial context for interpreting glacier terminus retreat rates and proglacial lake growth [

61], which itself accelerates shortening of the glacier tongue by enhancing ablation rates because of the relatively warm lake water, and potentially also promoting mass loss through calving.

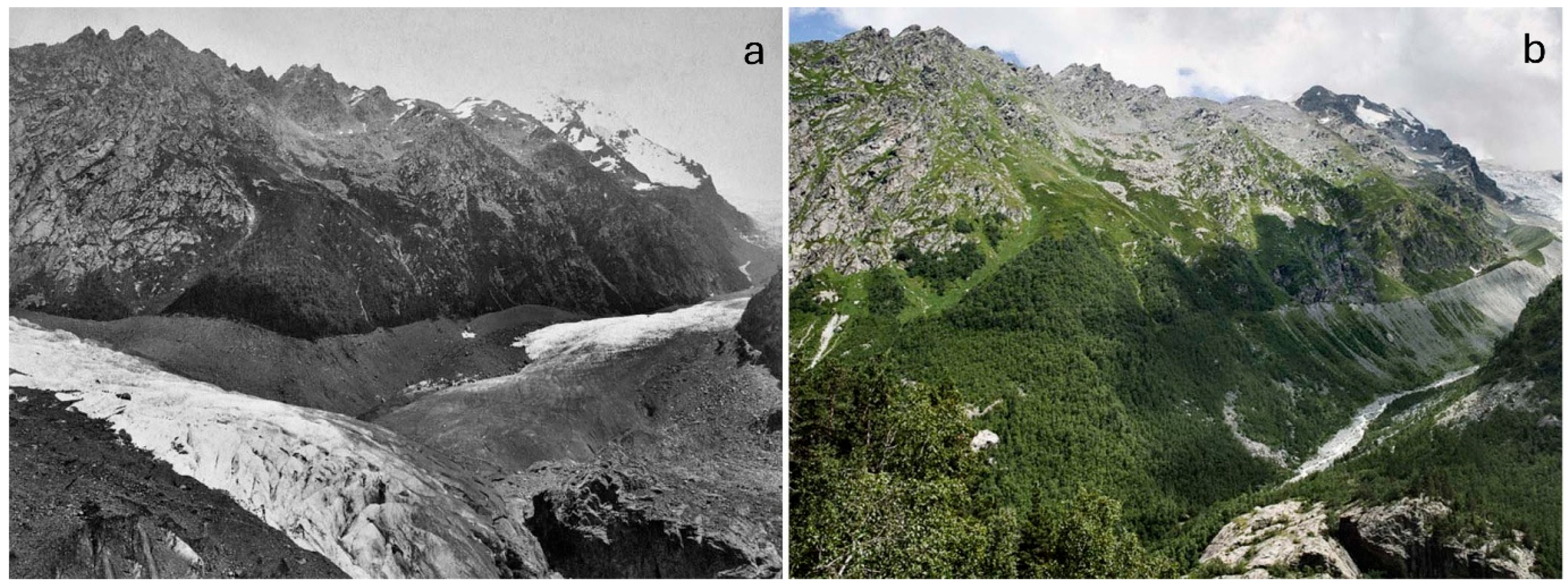

5.2. Historical Photographs and Evidence of Fragmentation

Historical photographs from the late 19th century, compared with modern images, provide striking visual evidence of the Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier transformation. Mor von Dechy’s 1884 photographs capture the massive, unified tongues of Tsaneri and Nageba, which at that time still formed a broad confluence filling the valley floor (

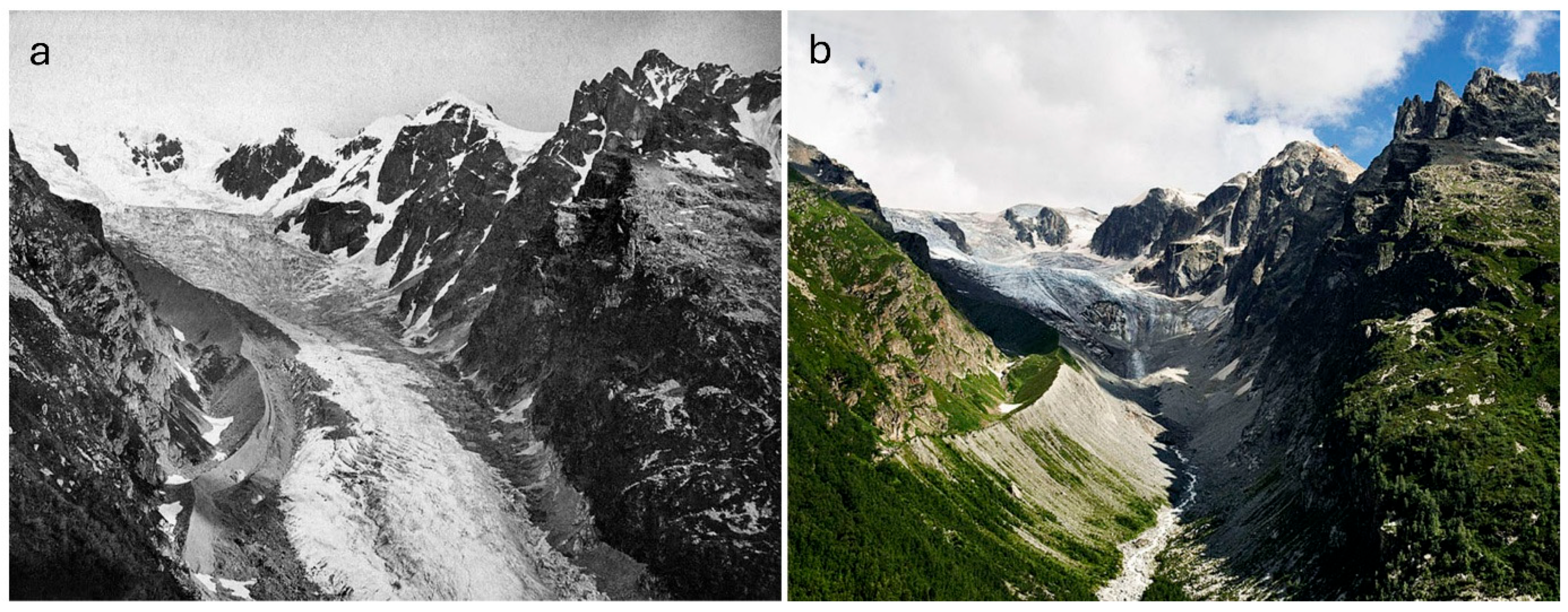

Figure 9). By 2011, photographs by Fabiano Ventura show a completely different scene: the confluence area entirely deglaciated, replaced by exposed moraine deposits, unstable slopes, and proglacial streams. Further photo comparisons (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11) of the middle parts reveal dramatic thinning, margin downwasting, and detachment of tributary glaciers.

These visual records complement cartographic and satellite evidence, demonstrating how Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier evolved from a single coherent ice mass into fragmented valley glaciers.

5.3. Hydrologic Implications for the Mulkhura–Enguri River System

The shrinkage of Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier has direct consequences for the Mulkhura–Enguri river catchment. Deglaciation reduces the glacier’s ability to buffer late-summer baseflows, leading to greater variability in discharge [

62]. In the short term, enhanced melt has increased summer runoff, but as glacier volume diminishes, the long-term trend will be toward reduced water availability in late summer and autumn [

2]. This seasonal imbalance poses risks for local communities relying on consistent water supply, as well as for downstream hydropower (HP) operations, such as Enguri HP, the largest in the region that depend on regulated discharge.

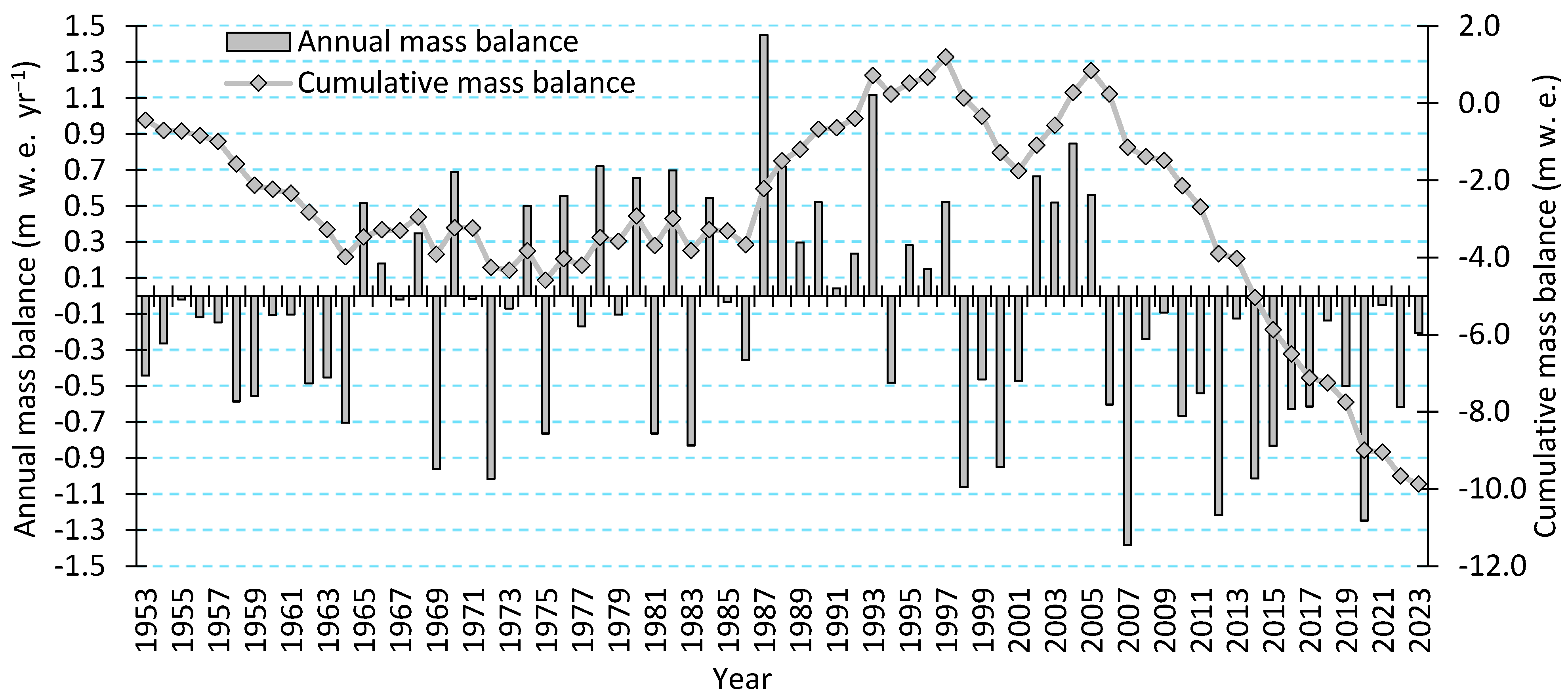

Geodetic mass balance data (

Figure 12) show strongly negative values since the early-21st century [

63], consistent with the increased retreat patterns observed in our mapping. These losses highlight a turning point: while meltwater contributions may remain elevated in the near term, they will eventually decline, leading to diminished water resources [

64]. Seasonal redistribution of runoff may also result in more frequent low-flow conditions during warm, dry years [

65]. Such changes underscore the importance of monitoring glacier-fed systems like Tsaneri–Nageba for sustainable water management.

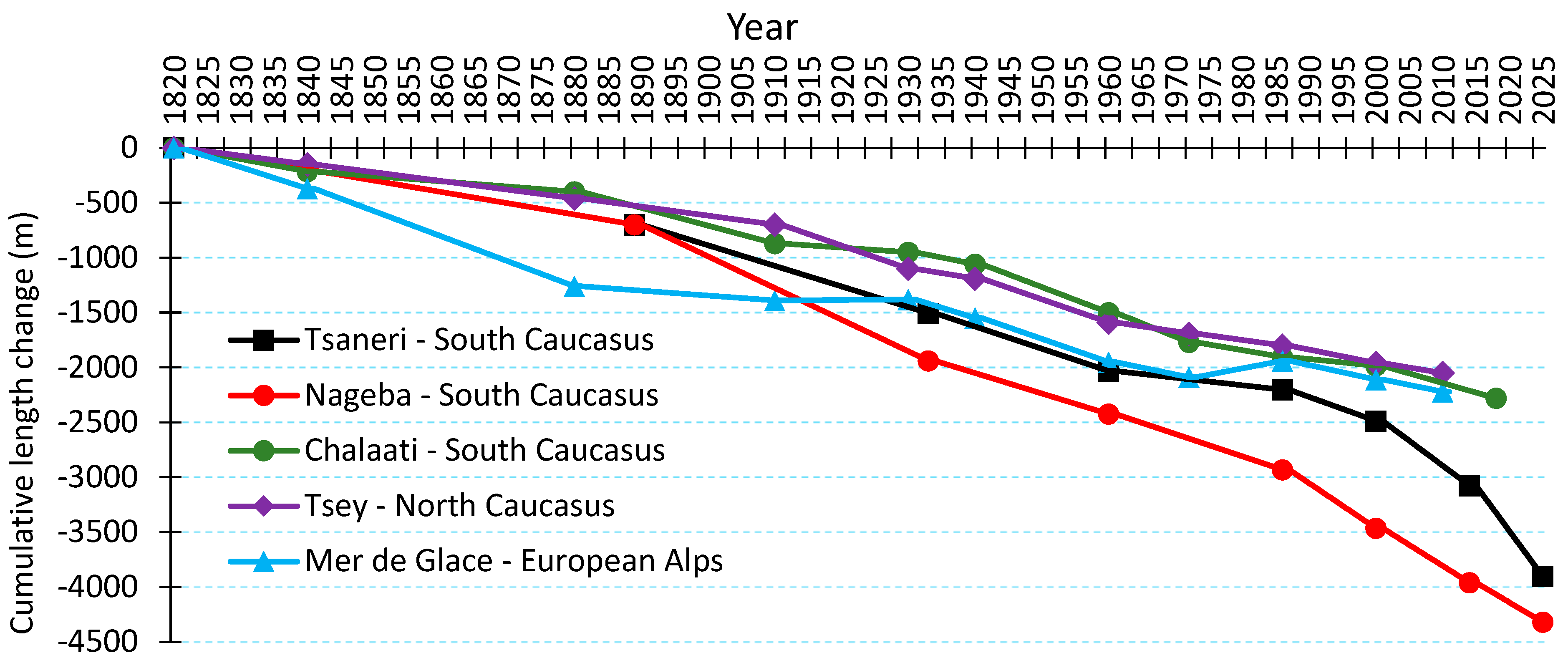

Comparisons with other glaciers (

Figure 13) demonstrate that the retreat of Tsaneri and Nageba has been among the most pronounced in the Greater Caucasus (e.g., Chalaati and Tsey glaciers [

15,

17]), exceeding that of some Alpine counterparts (e.g., Mer De Glace [

8]). This exceptional retreat emphasizes both the sensitivity of the Mulkhura–Enguri river system and the urgency of integrating glacier change into regional water resource planning and hazard mitigation.

5.4. Paraglacial Hazards and Geomorphic Adjustment

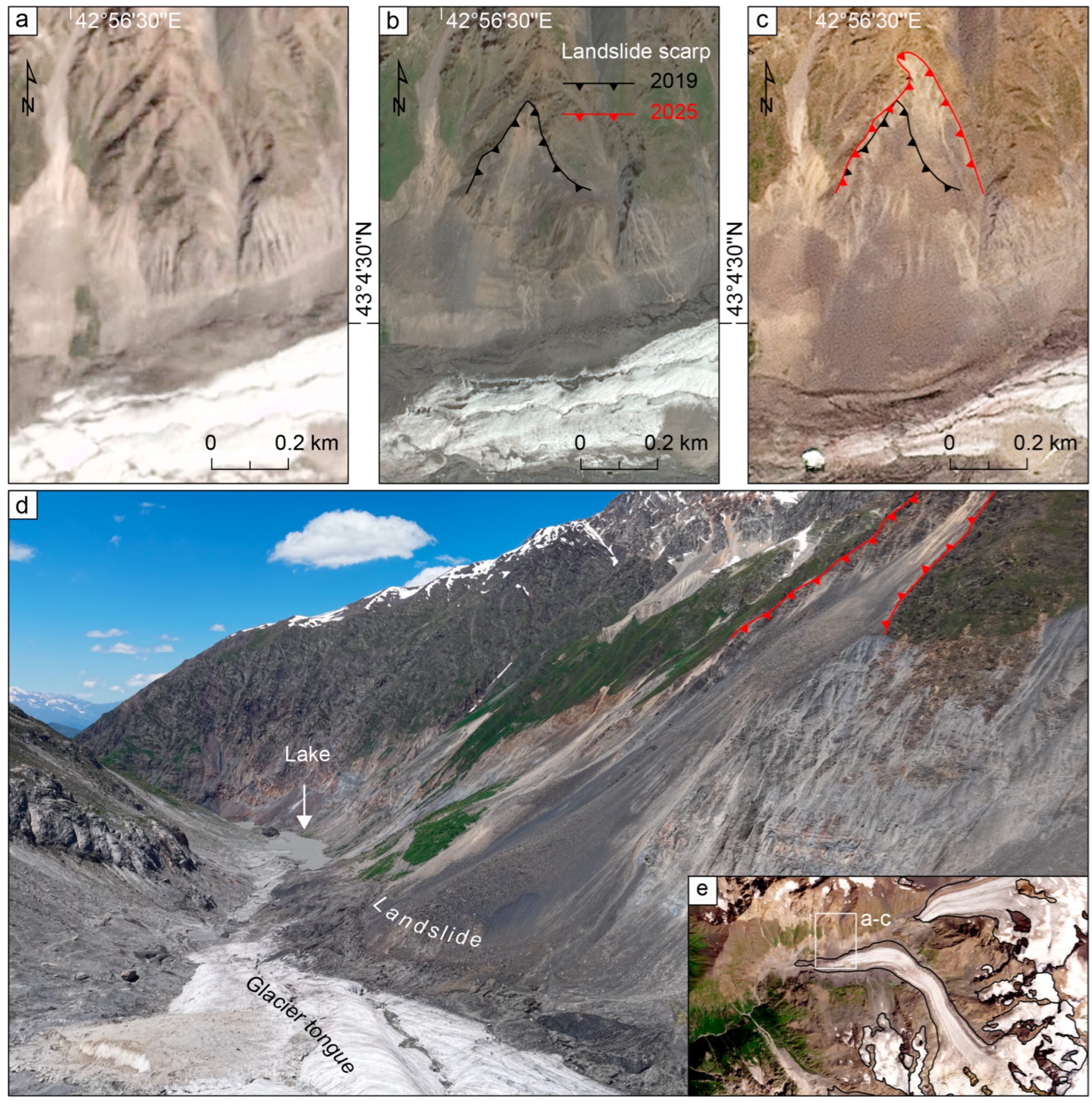

Rapid deglaciation of the Tsaneri–Nageba system has initiated a group of paraglacial adjustments, including slope instability (the landslide on the true right slope of the glacier tongue—43°4′32.32″ N 42°56′38.84″ E) (

Figure 14), moraine degradation, and proglacial lake expansion. As the glacier has thinned and retreated, steep headwalls and unconsolidated moraine deposits have become increasingly unstable, heightening the risk of rockfalls, debris flows, and moraine breaches. These processes are already visible in the proglacial zone, where small landslides and seepage channels suggest active instability.

The most notable development is the emergence of the proglacial lake in front of the Southern Tsaneri Glacier tongue. Although currently modest in volume (~639,800 m

3), the lake is expanding rapidly and is bounded by unconsolidated moraines and steep slopes (

Figure 15), making it susceptible to catastrophic failure. Potential triggers include slope collapses [

66], rock-ice avalanches [

67,

68], or seismic events [

41] that generate mass movements that impact the lake [

69,

70], all of which could produce a glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF). Given the steep, confined valley downstream, such an event could propagate quickly and cause severe impacts on infrastructure and communities.

Monitoring of the proglacial lake is therefore critical [

71]. UAV and sonar surveys provide a robust baseline for future change detection, but regular repeat surveys and hydrodynamic modeling of potential outburst scenarios are urgently needed. Hazard assessments should incorporate moraine stability analysis, slope stability modeling, and potential flood routing to downstream settlements. Installing an early warning system could also be beneficial for event prevention and for safeguarding communities living downstream of the valley. Integrating local knowledge with scientific monitoring will be essential for effective risk reduction.

The Tsaneri–Nageba system is an example of the interconnected processes of deglaciation (

Video S1), lake formation, and paraglacial hazard development in the Greater Caucasus. The glacier’s retreat has not only transformed the high-mountain landscape but also generated new hazards that require proactive management [

72]. Sustained interdisciplinary monitoring, including glaciology, geomorphology, hydrology, and hazard science, is essential to safeguard lives and livelihoods in the Mulkhura–Enguri river basin.

6. Conclusions

The Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier system provides one of the most striking case studies of post-Little Ice Age (LIA) deglaciation in the Greater Caucasus. By integrating geomorphological evidence, historical maps, multi-temporal satellite data, UAV photogrammetry, and sonar bathymetry, this study has reconstructed more than two centuries of glacier evolution and documented the emergence of a new proglacial lake.

Our results demonstrate that Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier has undergone a sustained and accelerating retreat since its LIA maximum (~1820). Climatic forcing such as an increase in summer air temperatures along with decreased winter precipitation provides a consistent explanation for these patterns.

A defining feature of Tsaneri’s recent evolution has been the formation of a proglacial lake. First detectable in satellite imagery from 2015, the lake has since expanded rapidly.

From a geomorphic perspective, the transition from glacial to paraglacial landscapes is well under way. Retreating ice has exposed steep slopes, unstable moraines, and overdeepened basins, all of which are prone to rapid adjustment. Evidence of small landslides, moraine breaches, and seepage channels suggests that the system is already experiencing increased instability. As retreat continues, these processes are likely to intensify, underscoring the need for systematic monitoring.

Several implications and recommendations arise from this work:

1—Regular UAV and satellite surveys of Tsaneri Glacier and its proglacial lake are essential to track ongoing changes. Repeat bathymetric measurements will be particularly valuable in detecting lake deepening and volume increase.

2—Given the lake’s rapid expansion and unstable moraine boundaries, detailed GLOF modeling should be undertaken. This should include moraine stability analysis, potential triggers (avalanches, rockfalls, earthquakes), and downstream flood routing.

3—Installing an early warning system, coupled with community-based preparedness strategies, could minimize the risks of potential GLOFs and safeguard downstream settlements and infrastructure.

4—Long-term projections of glacier runoff should be integrated into water resource planning for the Enguri River basin. Anticipating reduced late-summer flows will be critical for sustaining hydropower and local water supply.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w17223209/s1, Video S1: The MP4 video file illustrating the three-dimensional, time-lapse reconstruction of glacier geometry and thickness changes in the Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier system for the years 1820, 1889, 1933, 1960, 1986, 2000, 2014, and 2025.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G.T.; Formal analysis, L.G.T., A.N., R.M.K. and M.L.; Investigation, L.G.T., A.N. and R.M.K.; Methodology, L.G.T., A.N. and M.L.; Software, L.G.T., A.N. and M.L.; Visualization, L.G.T.; Writing—original draft, L.G.T.; Writing—review and editing, L.G.T., A.N., R.M.K., S.J.C., M.L., Q.L., I.M., A.N.M. and G.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation of Georgia (SRNSFG; grant no FR-23-4258) and by the International Education Center (IEC) of Georgia. SJC thanks the Royal Society of Edinburgh Small Grants scheme (Award No. 4924). QL thanks National Natural Science Foundation of China Sustainable Development International Cooperation Program (42361144874).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Border Police of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia for their support and provision of a helicopter for conducting field work. We also thank Mikheil Nikuradze, Giorgi Guliashvili, and Vitali Machavariani, for their help in the field. We sincerely thank three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments, which improved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Haeberli, W.; Hoelzle, M.; Paul, F.; Zemp, M. Integrated monitoring of mountain glaciers as key indicators of global climate change: The European Alps. Ann. Glaciol. 2007, 46, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, R.; Rasul, G.; Adler, C.; Cáceres, B.; Gruber, S.; Hirabayashi, Y.; Jackson, M.; Kääb, A.; Kang, S.; Kutuzov, S.; et al. High Mountain Areas. In IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate; Pörtner, H.O., Roberts, D.C., Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Nicolai, M., Okem, A., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 131–202. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; p. 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomina, O.N.; Bradley, R.S.; Jomelli, V.; Geirsdottir, A.; Kaufman, D.S.; Koch, J.; McKay, N.P.; Masiokas, M.; Miller, G.; Nesje, A.; et al. Glacier fluctuations during the past 2000 years. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016, 149, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta, S.; Azzoni, R.S.; Fugazza, D.; Tielidze, L.; Chand, P.; Sieron, K.; Almond, P.; Ambrosini, R.; Anthelme, F.; Gazitúa, P.A.; et al. The Retreat of Mountain Glaciers since the Little Ice Age: A Spatially Explicit Database. Data 2021, 6, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Carrivick, J.L.; Quincey, D.J.; Cook, S.J.; James, W.H.M.; Brown, L.E. Accelerated mass loss of Himalayan glaciers since the Little Ice Age. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, T.H.; Flanner, M.G.; Kaser, G.; Marzeion, B.; VanCuren, R.A.; Abdalati, W. End of the Little Ice Age in the Alps forced by industrial black carbon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 15216–15221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumbühl, H.; Nussbaumer, S. Little Ice Age glacier history of the Central and Western Alps from pictorial documents. Cuad. Investig. Geogr. 2018, 44, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrivick, J.L.; Davies, M.; Wilson, R.; Davies, B.J.; Gribbin, T.; King, O.; Rabatel, A.; García, J.; Ely, J.C. Accelerating glacier area loss across the Andes since the little ice age. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL109154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnia, B.F. Late nineteenth to early twenty-first century behavior of Alaskan glaciers as indicators of changing regional climate. Glob. Planet. Change 2007, 56, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjerde, M.; Hoel, O.L.; Nesje, A. The ‘Little Ice Age’ advance of Nigardsbreen, Norway: A cross-disciplinary revision of the chronological framework. Holocene 2023, 33, 1362–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutuzov, S.; Shahgedanova, M. Glacier retreat and climatic variability in the eastern Terskey–Alatoo, inner Tien Shan between the middle of the 19th century and beginning of the 21st century. Glob. Planet. Change 2009, 69, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganyushkin, D.; Chistyakov, K.; Derkach, E.; Bantcev, D.; Kunaeva, E.; Terekhov, A.; Rasputina, V. Glacier Recession in the Altai Mountains after the LIA Maximum. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushueva, I.S.; Solomina, O.N. Fluctuations of Kashkatash glacier over last 400 years using cartographic, dendrochronologic and lichonometric data. Ice Snow 2012, 52, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tielidze, L.G.; Solomina, O.N.; Jomelli, V.; Dolgova, E.A.; Bushueva, I.S.; Mikhalenko, V.N.; Brauche, R.; ASTER Team. Change of Chalaati Glacier (Georgian Caucasus) since the Little Ice Age based on dendro-chronological and Beryllium-10 data. Ice Snow 2020, 60, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tielidze, L.G.; Mackintosh, A.N.; Gavashelishvili, A.; Gadrani, L.; Nadaraia, A.; Elashvili, M. Post-Little Ice Age Equilibrium-Line Altitude and Temperature Changes in the Greater Caucasus Based on Small Glaciers. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomina, O.; Bushueva, I.; Dolgova, E.; Jomelli, V.; Alexandrin, M.; Mikhalenko, V.; Matskovsky, V. Glacier variations in the Northern Caucasus compared to climatic reconstructions over the past millennium. Glob. Planet. Change 2016, 140, 28–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomina, O.; Jomelli, V.; Bushueva, I.S. Chapter 19—Holocene glacier variations in the Northern Caucasus, Russia. In European Glacial Landscapes, The Holocene; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shugar, D.H.; Burr, A.; Haritashya, U.K.; Kargel, J.S.; Watson, C.S.; Kennedy, M.C.; Bevington, A.R.; Betts, R.A.; Harrison, S.; Strattman, K. Rapid worldwide growth of glacial lakes since 1990. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lützow, N.; Veh, G.; Korup, O. A global database of historic glacier lake outburst floods. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 2983–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrivick, J.L.; Tweed, F.S. Proglacial lakes: Character, behaviour and geological importance. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2013, 78, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, O.; Dehecq, A.; Quincey, D.; Carrivick, J. Contrasting geometric and dynamic evolution of lake and land-terminating glaciers in the central Himalaya. Glob. Planet. Change 2018, 167, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, J.L.; Carrivick, J.L.; Gandy, N.; Shulmeister, J.; Quincey, D.J.; Cornford, S.L. Proglacial lakes control glacier geometry and behavior during recession. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL088865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, J.-C. Proglacial Lakes in High Mountain Environments. In Geomorphology of Proglacial Systems. Geography of the Physical Environment; Heckmann, T., Morche, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rounce, D.R.; Watson, C.S.; McKinney, D.C. Identification of Hazard and Risk for Glacial Lakes in the Nepal Himalaya Using Satellite Imagery from 2000–2015. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veh, G.; Korup, O.; Walz, A. Hazard from Himalayan glacier lake outburst floods. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, S.; Kargel, J.S.; Huggel, C.; Reynolds, J.; Shugar, D.H.; Betts, R.A.; Emmer, A.; Glasser, N.; Haritashya, U.K.; Klimeš, J.; et al. Climate change and the global pattern of moraine-dammed glacial lake outburst floods. Cryosphere 2018, 12, 1195–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veh, G.; Lützow, N.; Kharlamova, V.; Petrakov, D.; Hugonnet, R.; Korup, O. Trends, Breaks, and Biases in the Frequency of Reported Glacier Lake Outburst Floods. Earth’s Futur. 2022, 10, e2021EF002426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.; Robinson, T.R.; Dunning, S.; Carr, J.R.; Westoby, M. Glacial lake outburst floods threaten millions globally. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrakov, D.A.; Krylenko, I.V.; Chernomorets, S.S.; Tutubalina, O.V.; Krylenko, I.N.; Shakhmina, M.S. Debris flow hazard of glacial lakes in the Central Caucasus. Debris-Flow Hazards Mitigation: Mechanics, Prediction, and Assessment. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Debris-Flow Hazards Mitigation, Chengdu, China, 10–13 September 2007; Chen, C., Major, J.J., Eds.; Millpress: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. ISBN 978 90 5966 059 5. [Google Scholar]

- Chernomorets, S.; Petrakov, D.; Aleynikov, A.A.; Bekkiev, M.Y.; Viskhadzhieva, K.; Dokukin, M.D.; Kalov, R.; Kidyaeva, V.; Krylenko, V.; Krylenko, I.V.; et al. The outburst of Bashkara glacier lake (Central Caucasus, Russia) on September 1, 2017. Earth’s Cryosphere 2018, 22, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kornilova, E.D.; Krylenko, I.N.; Rets, E.P.; Motovilov, Y.G.; Bogachenko, E.M.; Krylenko, I.V.; Petrakov, D.A. Modeling of Extreme Hydrological Events in the Baksan River Basin, the Central Caucasus, Russia. Hydrology 2021, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlyukevich, E.D.; Krylenko, I.N.; Krylenko, I.V. Modern evolution and hydrological regime of the Bashkara Glacier Lakes system (Central Caucasus, Russia) after the outburst on September 1, 2017. Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 2024, 17, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tielidze, L.G. Glacier change over the last century, Caucasus Mountains, Georgia, observed from old topographical maps, Landsat and ASTER satellite imagery. Cryosphere 2016, 10, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruashvili, L. Kavkasiis Fizikuri Geografia (Physical Geography of the Caucasus), Monograph; Publ. “Metsniereba”: Tbilisi, Georgia, 1981. (In Georgian) [Google Scholar]

- Elizbarashvili, M.; Beglarashvili, N.; Pipia, M.; Elizbarashvili, E.; Chikhradze, N. Seasonal Temperature and Precipitation Patterns in Caucasus Landscapes. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamia, S.; Zakariadze, G.; Chkhotua, T.; Sadradze, N.; Tsereteli, N.; Chabukiani, A.; Gventsadze, A. Geology of the Caucasus: A Review. Turk. J. Earth Sci. 2011, 20, 489–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumladze, R.M.; Tielidze, L.G.; Gamkrelidze, M.; Cook, S.J.; Giorgadze, A. Geology of the Mulkhura River Valley, Georgian Caucasus. Geosciences 2024, 14, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobejishvili, R.; Lomidze, N.; Tielidze, L. Late Pleistocene (Wurmian) glaciations of the Caucasus. In Quaternary Glaciations: Extent and Chronology; Ehlers, J., Gibbard, P.L., Hughes, P.D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revaz, K.; Koba, K.; Kukuri, T.; Giorgi, C. Ancient Glaciation of the Caucasus. Open J. Geol. 2018, 8, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail-Zadeh, A.; Adamia, S.; Chabukiani, A.; Chelidze, T.; Cloetingh, S.; Floyd, M.; Gorshkov, A.; Gvishiani, A.; Ismail-Zadeh, T.; Kaban, M.K.; et al. Geodynamics, seismicity, and seismic hazards of the Caucasus. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 207, 103222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volodicheva, N. The Caucasus. In The Physical Geography of Northern Eurasia; Shahgedanova, M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 350–376. [Google Scholar]

- Tielidze, L.G.; Nosenko, G.A.; Khromova, T.E.; Paul, F. Strong acceleration of glacier area loss in the Greater Caucasus between 2000 and 2020. Cryosphere 2022, 16, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tielidze, L.G.; Iacob, G.; Holobâcă, I.H. Mapping of Supra-Glacial Debris Cover in the Greater Caucasus: A Semi-Automated Multi-Sensor Approach. Geosciences 2024, 14, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkovskaya, V.A. Sections: Upper Svaneti Glaciers in the book ‘Caucasus the Glacier Regions’. Trans. Glacial Exped. 1936, 5, 404–448. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tielidze, L.G.; Wheate, R.D. The Greater Caucasus Glacier Inventory (Russia, Georgia and Azerbaijan). Cryosphere 2018, 12, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASFDAAC. ALOS PALSAR—Radiometric Terrain Correction—High Resolution. Includes Material © JAXA/METI. 2007. Accessed Through ASF DAAC. 2015. Available online: https://vertex.daac.asf.alaska.edu (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Hall, D.K.; Bayr, K.J.; Schöner, W.; Bindschadler, R.A.; Chien, J.Y. Consideration of the errors inherent in mapping historical glacier positions in Austria from the ground and space (1893–2001). Remote Sens. Environ. 2003, 86, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahgedanova, M.; Nosenko, G.; Kutuzov, S.; Rototaeva, O.; Khromova, T. Deglaciation of the Caucasus Mountains, Russia/Georgia, in the 21st century observed with ASTER satellite imagery and aerial photography. Cryosphere 2014, 8, 2367–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, C.R.; Shahgedanova, M.; Evans, I.S.; Popovnin, V.V. Accelerated loss of alpine glaciers in the Kodar Mountains, south-eastern Siberia. Glob. Planet. Change 2013, 101, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racoviteanu, A.E.; Arnaud, Y.; Williams, M.W.; Manley, W.F. Spatial patterns in glacier characteristics and area changes from 1962 to 2006 in the Kanchenjunga–Sikkim area, eastern Himalaya. Cryosphere 2015, 9, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, C.M.; Barr, I.D.; Mullan, D.; Ruffell, A. Rapid glacial retreat on the Kamchatka Peninsula during the early 21st century. Cryosphere 2016, 10, 1809–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, M.; Fischer, M. Sensitivity of Very Small Glaciers in the Swiss Alps to Future Climate Change. Front. Earth Sci. 2016, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, C.R.; Gurney, S.D.; Shahgedanova, M.; Popovnin, V. Late-20th-century changes in glacier extent in the Caucasus Mountains, Russia/Georgia. J. Glaciol. 2006, 52, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tielidze, L.G.; Svanadze, D.; Gadrani, L.; Asanidze, L.; Wheate, R.D.; Hamilton, G.S. A 54-year record of changes at Chalaati and Zopkhito glaciers, Georgian Caucasus, observed from archival maps, satellite imagery, drone survey and ground-based investigation. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2020, 69, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rototaeva, O.V.; Nosenko, G.A.; Kerimov, A.M.; Kutuzov, S.S.; Lavrentiev, I.I.; Nikitin, S.A.; Kerimov, A.A.; Tarasova, L.N. Changes of the mass balance of the Garabashy Glacier, Mount Elbrus, at the turn of 20th and 21st centuries. Ice Snow 2019, 59, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keggenhoff, I.; Elizbarashvili, M.; King, L. Heat Wave Events over Georgia Since 1961: Climatology, Changes and Severity. Climate 2015, 3, 308–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedler, M.; Pinto, J.G.; Hochman, A. More frequent, persistent, and deadly heat waves in the 21st century over the Eastern Mediterranean. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 870, 161883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, S.J. Regime Shifts in Glacier and Ice Sheet Response to Climate Change: Examples from the Northern Hemisphere. Front. Clim. 2021, 3, 702585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashilova, A.A.; Ashabokov, B.A.; Kesheva, L.A.; Teunova, N.V. Analysis of Climate Change in the Caucasus Region: End of the 20th–Beginning of the 21st Century. Climate 2019, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Zhang, G.; Chen, W.; Xu, F. Response of glacial lakes to glacier and climate changes in the western Nyainqentanglha range. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 735, 139607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, S.N.; Nienow, P.W. Decadal-Scale Climate Forcing of Alpine Glacial Hydrological Systems. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 2478–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussaillant, I.; Hugonnet, R.; Huss, M.; Berthier, E.; Bannwart, J.; Paul, F.; Zemp, M. Annual mass change of the world’s glaciers from 1976 to 2024 by temporal downscaling of satellite data with in situ observations. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 1977–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, M.; Hock, R. Global-scale hydrological response to future glacier mass loss. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierauer, J.R.; Whitfield, P.H.; Allen, D.M. Climate controls on runoff and low flows in mountain catchments of western north america. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 7495–7510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinzin, S.; Zhang, G.; Sattar, A.; Wangchuk, S.; Allen, S.K.; Dunning, S.; Peng, M. GLOF hazard, exposure, vulnerability, and risk assessment of potentially dangerous glacial lakes in the Bhutan Himalaya. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Allen, S.K.; Zheng, G.; Liu, Q.; Stoffel, M. Large rock and ice avalanches frequently produce cascading processes in High Mountain Asia. Geomorphology 2024, 449, 109048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, W. Ice Avalanche-Triggered Glacier Lake Outburst Flood: Hazard Assessment at Jiongpuco, Southeastern Tibet. Water 2025, 17, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargel, J.S.; Leonard, G.J.; Shugar, D.H.; Haritashya, U.K.; Bevington, A.; Fielding, E.J.; Fujita, K.; Geertsema, M.; Miles, E.S.; Steiner, J.; et al. Geomorphic and geologic controls of geohazards induced by Nepals 2015 Gorkha earthquake. Science 2016, 351, aac8353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.L.; Harrison, S.; Wilson, R.; Emmer, A.; Kargel, J.S.; Cook, S.J.; Glasser, N.F.; Reynolds, J.M.; Shugar, D.H.; Yarleque, C. Shaking up assumptions: Earthquakes have rarely triggered andean glacier lake outburst floods. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2023GL105578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yao, T.; Huss, M.; Carrivick, J.L.; Bolch, T.; Li, X.; Zheng, G.; Peng, M.; Wang, X.; Steiner, J.; et al. A monitoring network for mitigating Himalayan glacial lake outburst floods. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2025, BAMS-D-24-0290.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GAPHAZ. Assessment of Glacier and Permafrost Hazards in Mountain Regions—Technical Guidance Document; Prepared by Allen, S.; Frey, H.; Huggel, C. et al. Standing Group on Glacier and Permafrost Hazards in Mountains (GAPHAZ) of the International Association of Cryospheric Sciences (IACS) and the International Permafrost Association (IPA); GAPHAZ: Zurich, Switzerland; Lima, Peru, 2017; 72p. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Location of the Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier basin. The base map is reproduced from Google Earth (17/10/2019; © Google Earth). Inset map shows the location of the Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier system in a regional context.

Figure 1.

Location of the Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier basin. The base map is reproduced from Google Earth (17/10/2019; © Google Earth). Inset map shows the location of the Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier system in a regional context.

Figure 2.

(a) Example of an old map (1889) and (b) satellite image (Planet 19/08/2025) used to map the Tsaneri-Naga Glacier within this study.

Figure 2.

(a) Example of an old map (1889) and (b) satellite image (Planet 19/08/2025) used to map the Tsaneri-Naga Glacier within this study.

Figure 3.

(a) High-resolution (5 cm) orthophoto of Tsaneri Proglacial Lake from the UAV survey conducted on 10 July 2025. Red dots indicate the sonar track. (b) Field photo showing the sonar survey. (c) Drone image of Tsaneri Proglacial Lake (10/07/2025), viewed from above the glacier tongue. (d) Inset map showing the location of the lake relative to the glacier tongue (Planet image – 19/08/2025).

Figure 3.

(a) High-resolution (5 cm) orthophoto of Tsaneri Proglacial Lake from the UAV survey conducted on 10 July 2025. Red dots indicate the sonar track. (b) Field photo showing the sonar survey. (c) Drone image of Tsaneri Proglacial Lake (10/07/2025), viewed from above the glacier tongue. (d) Inset map showing the location of the lake relative to the glacier tongue (Planet image – 19/08/2025).

Figure 4.

Methodological workflow of this study.

Figure 4.

Methodological workflow of this study.

Figure 5.

Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier decrease rates for different periods between 1820 and 2025.

Figure 5.

Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier decrease rates for different periods between 1820 and 2025.

Figure 6.

Map showing the Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier system decrease between 1820 and 2025. Planet image–19/08/2025 is used as a background.

Figure 6.

Map showing the Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier system decrease between 1820 and 2025. Planet image–19/08/2025 is used as a background.

Figure 7.

Mean summer (May-September) and sum of the winter (November-March) precipitation for Mestia weather station between 1936/1961 and 2024.

Figure 7.

Mean summer (May-September) and sum of the winter (November-March) precipitation for Mestia weather station between 1936/1961 and 2024.

Figure 8.

(a) Bathymetry of the Tsaneri proglacial lake and surface area. The green-yellow-red dots show the sonar track with the corresponding depths. (b) Inset map (Planet image–19/08/2025) showing the location of the lake relative to the glacier tongue.

Figure 8.

(a) Bathymetry of the Tsaneri proglacial lake and surface area. The green-yellow-red dots show the sonar track with the corresponding depths. (b) Inset map (Planet image–19/08/2025) showing the location of the lake relative to the glacier tongue.

Figure 9.

(a) Tsaneri and Nageba glaciers conjunction in 1884 (Photo by: Mor Von Dechy) and (b) same place in 2011 (Photo by: Fabiano Ventura).

Figure 9.

(a) Tsaneri and Nageba glaciers conjunction in 1884 (Photo by: Mor Von Dechy) and (b) same place in 2011 (Photo by: Fabiano Ventura).

Figure 10.

(a) Middle part of the Tsaneri Glacier in 1884 (Photo by: Mor Von Dechy) and (b) same place in 2011 (Photo by: Fabiano Ventura).

Figure 10.

(a) Middle part of the Tsaneri Glacier in 1884 (Photo by: Mor Von Dechy) and (b) same place in 2011 (Photo by: Fabiano Ventura).

Figure 11.

(a) Middle part of the Nageba Glacier in 1884 (Photo by: Mor Von Dechy) and (b) same place in 2011 (Photo by: Fabiano Ventura).

Figure 11.

(a) Middle part of the Nageba Glacier in 1884 (Photo by: Mor Von Dechy) and (b) same place in 2011 (Photo by: Fabiano Ventura).

Figure 12.

Geodetic mass balance of Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier system between 1953 and 2023. Data analyzed based on Dussaillant et al. [

63].

Figure 12.

Geodetic mass balance of Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier system between 1953 and 2023. Data analyzed based on Dussaillant et al. [

63].

Figure 13.

Tsaneri and Nageba glacier terminus retreat compared to other Caucasus [

15,

17] and Alpine glaciers [

8].

Figure 13.

Tsaneri and Nageba glacier terminus retreat compared to other Caucasus [

15,

17] and Alpine glaciers [

8].

Figure 14.

(a) Planet (24/08/2016), (b) SPOT6 (30/07/2019), and (c) Planet (19/08/2025) images showing the development of large landslide at the Southern Tsaneri Glacier tongue. (d) Drone image of the same landslide (10/07/2025), viewed from above the glacier tongue. (e) Inset map showing the location of the landslide relative to the glacier tongue.

Figure 14.

(a) Planet (24/08/2016), (b) SPOT6 (30/07/2019), and (c) Planet (19/08/2025) images showing the development of large landslide at the Southern Tsaneri Glacier tongue. (d) Drone image of the same landslide (10/07/2025), viewed from above the glacier tongue. (e) Inset map showing the location of the landslide relative to the glacier tongue.

Figure 15.

(a) Sentinel 2 (3/09/2015), (b) SPOT6 (30/07/2019), and (c) Planet (19/08/2025) images showing the evolution of the Tsaneri proglacial lake over the last ten years. Inset map (d) showing the location of the lake relative to the glacier tongue.

Figure 15.

(a) Sentinel 2 (3/09/2015), (b) SPOT6 (30/07/2019), and (c) Planet (19/08/2025) images showing the evolution of the Tsaneri proglacial lake over the last ten years. Inset map (d) showing the location of the lake relative to the glacier tongue.

Table 1.

Datasets used in this study for mapping of the glacier and proglacial lake.

Table 1.

Datasets used in this study for mapping of the glacier and proglacial lake.

| Product/Reference | ID | Date | Resolution/Scale |

|---|

| For glacier mapping |

| Military topographic map | XX-27 | 1889 | 1:42,000 |

| Rutkovskaya, 1936 [45] | - | 1933 (1936) | - |

| Military topographic map | K-38-26-g | 1960s | 1:50,000 |

| Military topographic map | K-38-27-v | 1960s | 1:50,000 |

| Landsat 5 TM | LT51710301986218XXX02 | 06/08/1986 | 30 m |

| Landsat 7 ETM+ | LT51710302000225AAA02 | 12/08/2000 | 15/30 m |

| Landsat 8 OLI TIRS | LC81710302014215LGN00 | 03/08/2014 | 15/30 m |

| Planet | 082723_45_2541_3B | 19/08/2025 | 3 m |

| ALOS PALSAR DEM | AP_08763_FBD_F0850_RT1 | 16/09/2007 | 12.5 m |

| For proglacial lake mapping |

| Sentinel | MSIL1C_PDMC_20170121T131324_R035_V20150903T075826 | 03/09/2015 | 10 m |

| SPOT6 | PMS_201907300739197_ORT_AKWOI-00035543_R1C2 | 30/07/2019 | 1 m |

| Planet | 20160824_071051_0e0f | 2/11/2016 | 3 m |

| Planet | 082723_45_2541_3B | 19/08/2025 | 3 m |

| Drone | - | 10/07/2025 | 5 cm |

| Sonar | - | 10/07/2025 | - |

Table 2.

Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier area decrease from 1820 to 2025.

Table 2.

Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier area decrease from 1820 to 2025.

| Year | Area (km2) | Uncertainty (km2) | Uncertainty (%) |

|---|

| 1820 | 47.99 | ±2.63 | ±5.5 |

| 1889 | 46.80 | ±2.52 | ±5.4 |

| 1933 | 42.89 | ±2.31 | ±5.4 |

| 1960 | 40.33 | ±1.69 | ±4.2 |

| 1986 | 37.93 | ±1.13 | ±3.0 |

| 2000 | 36.46 | ±1.02 | ±2.8 |

| 2014 | 33.17 | ±0.86 | ±2.6 |

| 2025 | 30.58 | ±0.64 | ±2.1 |

Table 3.

Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier total and percentage area loss for different periods between 1820 and 2025.

Table 3.

Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier total and percentage area loss for different periods between 1820 and 2025.

| Period | Area loss (km2) | Decrease (%) | Decrease (% yr−1) | Decrease (km2 yr−1) |

|---|

| 1820–1889 | −1.19 | −2.48 | −0.04 | −0.017 |

| 1889–1933 | −3.91 | −8.35 | −0.19 | −0.089 |

| 1933–1960 | −2.56 | −5.97 | −0.22 | −0.095 |

| 1960–1986 | −2.40 | −5.95 | −0.23 | −0.092 |

| 1986–2000 | −1.47 | −3.88 | −0.28 | −0.105 |

| 2000–2014 | −3.29 | −9.02 | −0.64 | −0.235 |

| 2014–2025 | −2.59 | −7.81 | −0.71 | −0.235 |

| Sum/Average | −17.41 | −43.46 | −0.21 | −0.085 |

Table 4.

Terminus retreat of Tsaneri and Nageba glaciers for different periods between 1820 and 2025. * Similar retreat rates between 1820 and 1899 are due to shared tongue/terminus for Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier by that time. ** Terminus retreat from 1986 is calculated based on the Southern Tsaneri tongue.

Table 4.

Terminus retreat of Tsaneri and Nageba glaciers for different periods between 1820 and 2025. * Similar retreat rates between 1820 and 1899 are due to shared tongue/terminus for Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier by that time. ** Terminus retreat from 1986 is calculated based on the Southern Tsaneri tongue.

| Year | Tsaneri | Nageba |

|---|

| Retreat | Retreat m yr−1 | Retreat | Retreat m yr−1 |

|---|

| * 1820–1889 | −700 | −10.1 | −700 | −10.1 |

| 1889–1933 | −806 | −18.3 | −1240 | −28.2 |

| 1933–1960 | −526 | −19.5 | −485 | −17.0 |

| 1960–1986 | −172 | −6.6 | −507 | −19.5 |

| ** 1986–2000 | −283 | −20.2 | −532 | −38.0 |

| 2000–2014 | −590 | −42.1 | −496 | −35.4 |

| 2014–2025 | −827 | −75.2 | −360 | −32.7 |

| Sum/Average | −3904 | −19.0 | −4320 | −21.1 |

Table 5.

Terminus elevation changes in Tsaneri and Nageba glaciers from 1820 to 2025. * Similar elevations for 1820 and 1899 are due to shared tongue/terminus for Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier by that time. The uncertainty of the elevation is ±12.5 m.

Table 5.

Terminus elevation changes in Tsaneri and Nageba glaciers from 1820 to 2025. * Similar elevations for 1820 and 1899 are due to shared tongue/terminus for Tsaneri–Nageba Glacier by that time. The uncertainty of the elevation is ±12.5 m.

| Year | Tsaneri | Nageba |

|---|

| Terminus Elevation (m a.s.l.) |

|---|

| * 1820 | 1976 | 1976 |

| * 1889 | 2102 | 2102 |

| 1933 | 2229 | 2307 |

| 1960 | 2334 | 2400 |

| 1986 | 2336 | 2536 |

| 2000 | 2343 | 2675 |

| 2014 | 2401 | 2851 |

| 2025 | 2440 | 2946 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).