Prototype-Scale Experimental Investigation of Manhole Cover Bounce and Critical Overpressure in Urban Drainage Shafts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Investigation

2.1. Experimental Apparatus

- (1)

- Air supply system: A screw-type air compressor (model JAC30B-8) had been employed, with a rated discharge capacity of 5.0 m3/min, a maximum discharge pressure of 0.8 MPa, a drive power of 36.8 kW, and a rated rotational speed of 2500 rpm. Compressed air had been delivered from the compressor to the downstream inspection chamber through the inlet pipe, which had been 5.0 m in length and 0.5 m in internal diameter.

- (2)

- Single-chamber structure: Each inspection chamber had been composed of a chamber body, a vertical shaft, and a hinged manhole cover. The internal dimensions of the chamber body had been 2.0 m × 1.9 m × 2.4 m; the vertical shaft had an internal diameter of 0.7 m and a height of 4.6 m; and the manhole cover had a diameter of 0.7 m and a self-weight of 25.0 kg. A single vent orifice had been installed on each manhole cover, with an orifice diameter of 0.04 m. Three pressure transducers (PT-1# to PT-3#) had been installed at equal vertical intervals from top to bottom, with a measurement range of 0–200 kPa, a sampling frequency ≥ 1 kHz, and an accuracy of 0.1%, in order to record the transient air pressure evolution within the shaft. The bouncing motion of the manhole cover had been recorded by high-speed cameras in two imaging formats: 1920 × 1080 at 100 fps and 2560 × 1600 at 50 fps, for back-calculating the rotation angle and the lift-off moment.

- (3)

- Dual-chamber connection: The center-to-center distance between the two inspection chambers in the actual engineering prototype had been approximately 80 m. Considering that this study had focused on the critical overpressure triggering and manhole cover response induced by localized air injection—and given that the speed of sound in air is relatively high (approximately 340 m/s)—a 10.0 m-long connecting pipe with an internal diameter of 0.5 m had been adopted to link the two chambers in the experiment, so as to accommodate laboratory space constraints while preserving the key time scales as closely as possible. Under this setup, the acoustic transmission time had been reduced from approximately 0.234 s in the prototype to 0.029 s in the experiment (about 1/8), but it still remained significantly smaller than the characteristic time of a single charge–release cycle. Given the high sampling frequency and temporal resolution of the pressure transducers and high-speed cameras used in the test, the response variations caused by this distance scaling had been considered adequately detectable, thereby ensuring the accuracy of experimental observations.

2.2. Experimental Conditions and Procedures

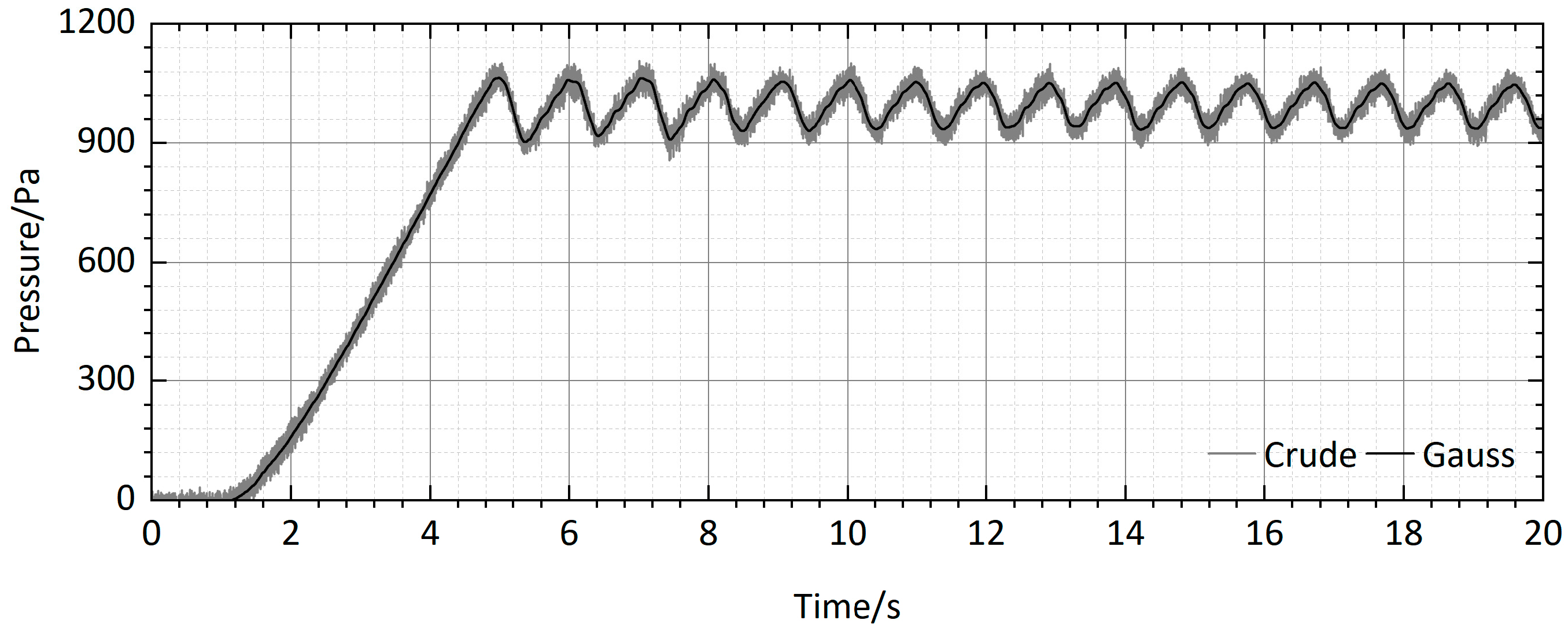

2.3. Comparison of Repeatability Tests

3. Simulation Results Analysis

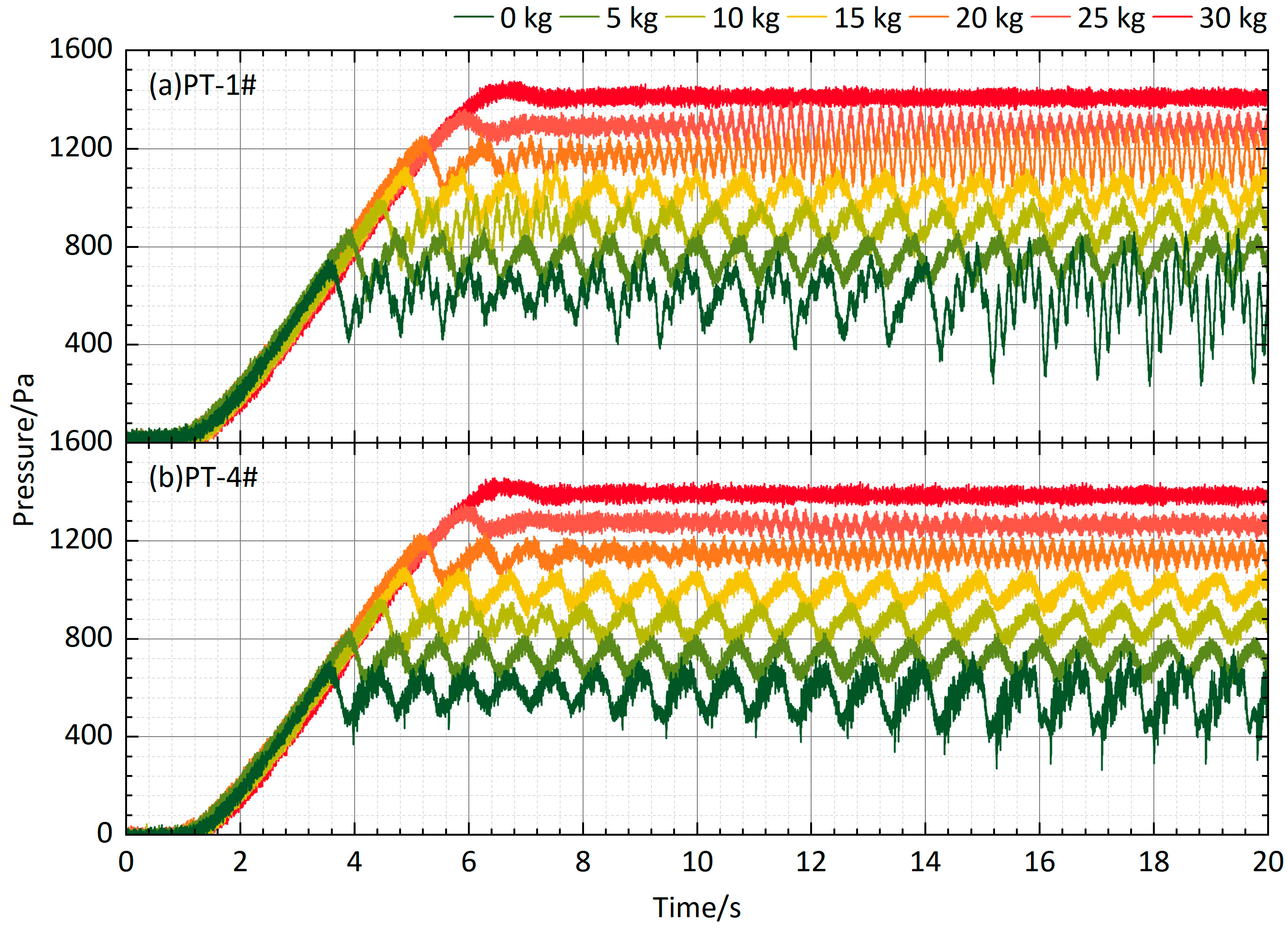

3.1. Bounce Response of a Single Manhole Cover

3.2. Bounce Response of Dual Manhole Covers

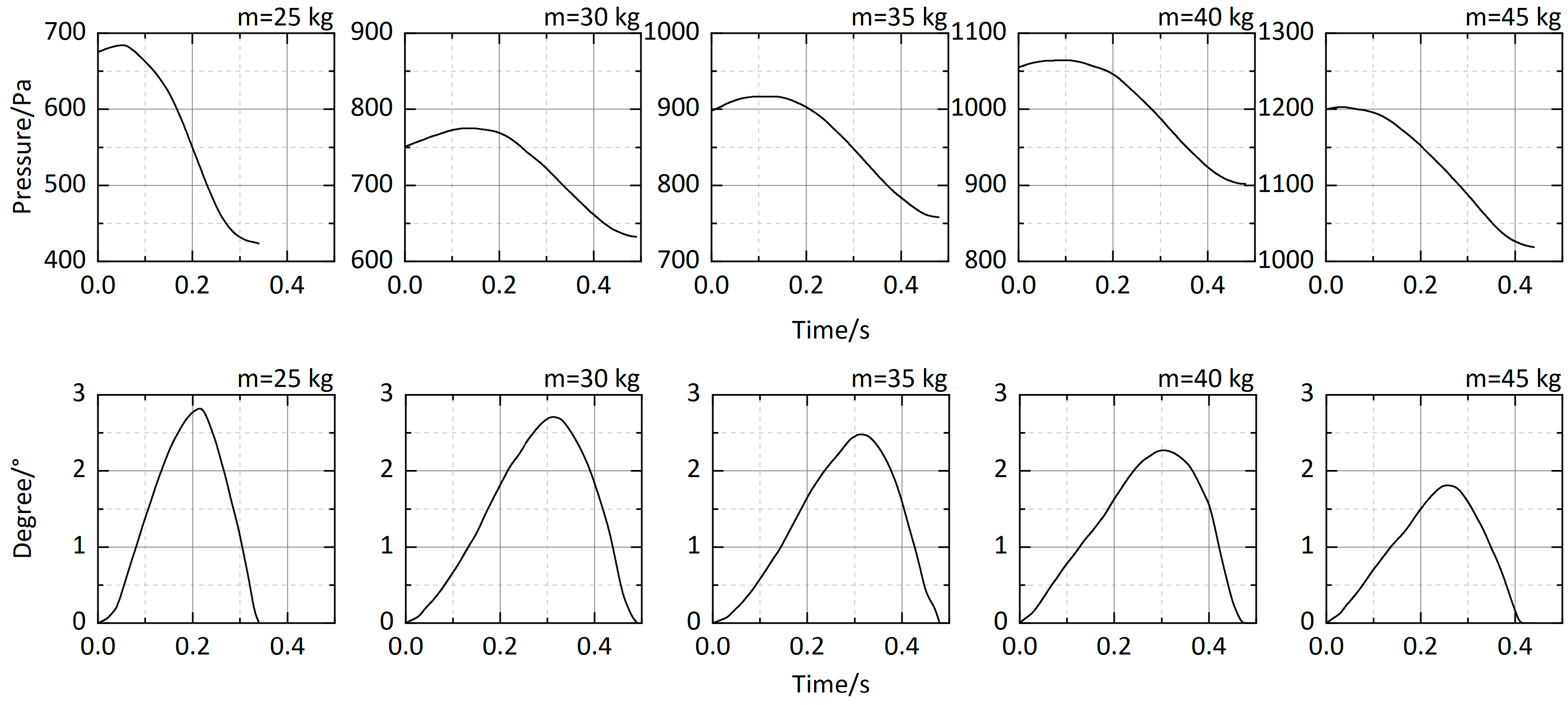

3.3. Temporal Correspondence and Amplitude Relationship Between Pressure and Displacement

4. Discussion

- (1)

- Source mitigation: Large trapped air pockets caused by rapid filling should be avoided as much as possible. This can be achieved through operational scheduling, controlled overflow, and pre-venting measures, all of which help reduce the risk of transient overpressure at its origin.

- (2)

- Process regulation: Ventilation structures should be optimized in terms of orifice size, layout, and the use of one-way or two-way valves. Pressure-relief or discharge devices should be installed in critical sections. Both experimental and numerical results confirm that venting boundaries are key levers in controlling overpressure magnitude.

- (3)

- Terminal protection: Without compromising maintenance safety, anti-lift structures (such as locking or limiting mechanisms) should be implemented, and the hinged cover structure and seat-ring sealing should be reinforced or weighted appropriately. This ensures a balanced capacity for both resisting bounce and allowing controllable venting under transient overpressure.

- (4)

- Monitoring and early-warning: Real-time monitoring of water level and transient pressure should be established with multi-level alert thresholds. Triggered warnings should link to operational protocols such as flow control or traffic restriction to enable proactive intervention.

5. Conclusions

- The critical overpressure required for initial bounce increases monotonically with counterweight. In this study, the lowest observed threshold was approximately 700 Pa. When the counterweight exceeded 25 kg, the cover failed to fully reseat after the first bounce, resulting in continuous air leakage and the absence of subsequent significant rebounds. Under such conditions, the system stabilized at an overpressure of approximately 1300 Pa.

- The trend observed in single-shaft cases—where the pressure fluctuation period initially increases and then decreases with increasing cover mass—no longer holds when both shafts undergo simultaneous bounce. In the dual-shaft configuration, the phase difference in venting and the coupled propagation effects dominate the subsequent fluctuation pattern and frequency, masking the mass–period relationship observed in single-shaft scenarios.

- The critical overpressure does not coincide with the peak of the pressure waveform. For counterweights of 25, 30, 35, 40, and 45 kg, the corresponding critical overpressures have been 675, 750, 915, 1064, and 1199 Pa, respectively, while the maximum rotation angles have been 2.82°, 2.71°, 2.48°, 2.26°, and 1.80°. In all cases, the pressure waveform reached a maximum value greater than the critical overpressure, indicating a pronounced phase lag in which the pressure peak precedes the peak displacement.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fang, H.; Zhou, L.; Cao, Y.; Cai, F.; Liu, D. 3D CFD simulations of air-water interaction in T-junction pipes of urban stormwater drainage system. Urban Water J. 2022, 19, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, A.S. Mechanisms that lead to violent geysers in vertical shafts. J. Hydraul. Res. 2019, 57, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Chai, F.; Zang, W.; Zhang, H.; Hao, X.; Xu, H. A Two-Level Early Warning System on Urban Floods Caused by Rainstorm. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Xie, Z.; Zhao, F.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, S.; Chen, S.; Li, X.; Zhao, S.; et al. Permeability control and flood risk assessment of urban underlying surface: A case study of Runcheng south area, Kunming. Nat. Hazards 2022, 111, 661–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Xia, J.; Wang, X. Comprehensive flood risk assessment in highly developed urban areas. J. Hydrol. 2025, 648, 132391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Yang, Z.; Shao, W.; Ding, X.; Weng, B.; Yu, Y.; Yan, D. Urban flood inundation and damage assessment based on numerical simulations of design rainstorms with different characteristics. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2020, 63, 2292–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Fang, J.; Dang, X.; Xu, K.; Fang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, M. Multi-scenario urban flood risk assessment by integrating future land use change models and hydrodynamic models. Nat. Hazard Earth Sys. 2022, 22, 3815–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shao, W.; Zhu, D.; Xu, W. Steady air flow model for large sewer networks: A theoretical framework. Water Sci. Technol. 2020, 82, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujawska, J.; Duda-Saternus, S.; Szulżyk-Cieplak, J.; Zaburko, J.; Piłat-Rożek, M.; Jamka, K.; Babko, R.; Łagód, G. Comparison of leaching behaviour of heavy metals from sediments sampled in sewer systems—Environmental and public health aspect. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2023, 30, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Shao, W.; Zhu, D.; Mohamad, K.; Steffler, P.; Edwini-Bonsu, S.; Yue, D.; Krywiak, D. Modeling air flow in sanitary sewer systems: A review. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2021, 38, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.; Sun, W.; Shen, S.; Arulrajah, A. Flood risk assessment in metro systems of mega-cities using a GIS-based modeling approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 626, 1012–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.; Shen, S.; Zhou, A.; Yang, J. Perspectives for flood risk assessment and management for mega-city metro system. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 84, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Meng, Q. A fine-scale spatial analytics of the assessment and mapping of buildings and population at different risk levels of urban flood. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Z. Depth prediction of urban flood under different rainfall return periods based on deep learning and data warehouse. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 716, 137077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Jin, Y.; Sun, S.; Yuan, Z.; Butler, D. The role of deep learning in urban water management: A critical review. Water Res. 2022, 223, 118973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadifar, A.; Gholami, H.; Golzari, S. Novel integrated modelling based on multiplicative long short-term memory (mLSTM) deep learning model and ensemble multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) models for mapping flood risk. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S. Mechanism Behind Manole Cover Ejection Phenomenon and Its Prevention Measures. In Global Solutions for Urban Drainage; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2002; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Vasconcelos, J. Manhole cover displacement caused by the release of entrapped air pockets. J. Water Manag. Modell. 2018, 26, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Vasconcelos, J. Investigation of manhole cover displacement during rapid filling of stormwater systems. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2020, 146, 04020022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijsseling, A.; Vasconcelos, J.; Hou, Q.; Bozkuş, Z. Dancing manhole cover: A nonlinear spring-mass system. In Proceedings of the Pressure Vessels and Piping Conference, San Antonio, TX, USA, 14–19 July 2019; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2019. 58950, V004T04A032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijsseling, A.; Vasconcelos, J.; Hou, Q.; Bozkuş, Z. Venting manhole cover: A nonlinear spring-mass system. In Proceedings of the Pressure Vessels and Piping Conference, Online, 3 August 2020; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2020. 83846, V004T04A011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Meulenhof, N.; Tijsseling, A.; Vasconcelos, J.; Hou, Q.; Bozkuş, Z. Tilting Manhole Cover: A Nonlinear Spring-Mass System. In Proceedings of the Pressure Vessels and Piping Conference, Bellevue, WA, USA, 28 July–2 August 2024; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2024. 88490, V003T04A002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Pan, T.; Wang, H.; Liu, D.; Wang, P. Rapid air expulsion through an orifice in a vertical water pipe. J. Hydraul. Res. 2019, 57, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Lu, Y.; Karney, B.; Wu, G.; Elong, A.; Huang, K. Energy dissipation in a rapid filling vertical pipe with trapped air. J. Hydraul. Res. 2023, 61, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Guo, X.; Xu, Z.; Yang, C. Experimental and numerical simulations of river-crossing pipelines for different water fill patterns. J. Hydraul. Res. 2024, 62, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeberg, T. Scale-space for discrete signals. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 12, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allasia, D.; Böck, L.; Vasconcelos, J.; Pinto, L.; Tassi, R.; Minetto, B.; Persch, C.; Pachaly, R.L. Experimental Study of Geysering in an Upstream Vertical Shaft. Water 2023, 15, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.; Ortiz, P. Propagation of large air pockets in ducts. Analytical and numerical approaches. Appl. Math. Model. 2022, 110, 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, H.; Liu, W.; Guo, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Dong, B.; Jia, X.; Zhou, K.; Zhou, L. Prototype-Scale Experimental Investigation of Manhole Cover Bounce and Critical Overpressure in Urban Drainage Shafts. Water 2025, 17, 3198. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223198

Zhao H, Liu W, Guo Z, Liu S, Wang D, Li Y, Dong B, Jia X, Zhou K, Zhou L. Prototype-Scale Experimental Investigation of Manhole Cover Bounce and Critical Overpressure in Urban Drainage Shafts. Water. 2025; 17(22):3198. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223198

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Hanxu, Wei Liu, Zaihong Guo, Shuyu Liu, Dongyi Wang, Yin Li, Baifeng Dong, Xiangyu Jia, Kaifeng Zhou, and Ling Zhou. 2025. "Prototype-Scale Experimental Investigation of Manhole Cover Bounce and Critical Overpressure in Urban Drainage Shafts" Water 17, no. 22: 3198. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223198

APA StyleZhao, H., Liu, W., Guo, Z., Liu, S., Wang, D., Li, Y., Dong, B., Jia, X., Zhou, K., & Zhou, L. (2025). Prototype-Scale Experimental Investigation of Manhole Cover Bounce and Critical Overpressure in Urban Drainage Shafts. Water, 17(22), 3198. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223198