Advances in Microbial Bioremediation for Effective Wastewater Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Microbial Remediation Strategies and Technologies

2.1. Bioaugmentation and Biostimulation

2.2. Sequencing Batch Reactors (SBRs)

2.3. Novel Microbial Communities and Synthetic Consortia

2.4. Immobilized Microorganisms

3. Microbial Communities in Wastewater Treatment: A Pillar of Sustainable Sanitation

3.1. Bacteria: The Workhorses of Wastewater Treatment

3.2. Protozoa: Biological Clarifiers

3.3. Fungi: Degraders of Complex Organic Pollutants

3.4. Algae: Photosynthetic Partners

3.5. Other Organisms: Metazoans and Bacteriophages

3.6. Integrated Microbial Ecosystems in Action

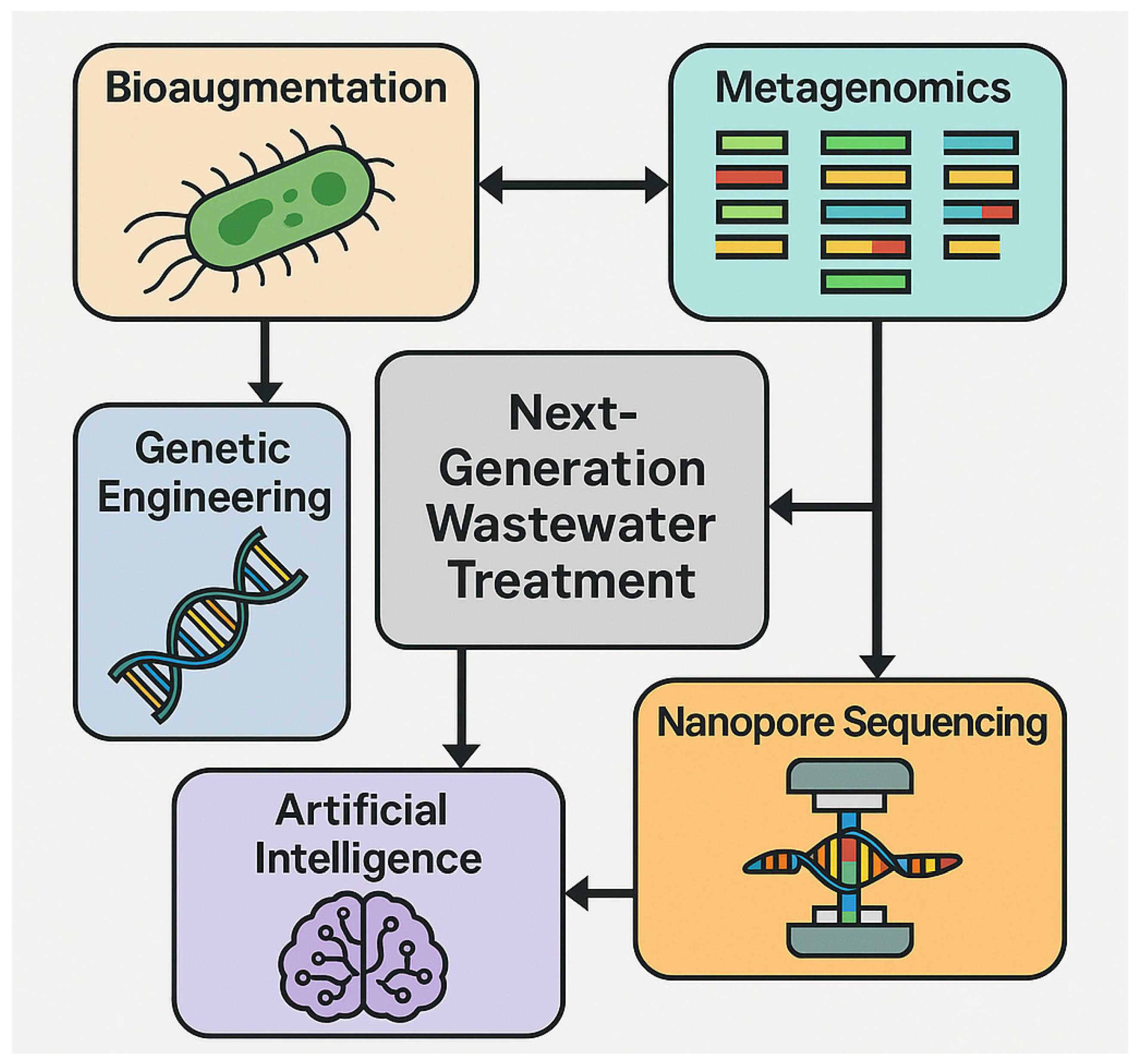

4. Recent Advancement

4.1. Genetic and Metabolic Engineering

4.2. Key Engineered Microbial Systems

4.2.1. Bacteria

- Heavy Metal Detoxification: Engineered strains of Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and others express metal-binding proteins (e.g., metallothioneins, phytochelatins) or reductive enzymes to remove cadmium, lead, mercury, and arsenic [60,61]. For instance, B. subtilis modified to express an arsenite methyltransferase from Cyanidioschyzon merolae can convert toxic arsenic into less harmful methylated forms [62].

- Organic Pollutant Degradation: Vibrio natriegens (VCOD-15) was engineered with five gene clusters enabling simultaneous degradation of biphenyl, phenol, naphthalene, dibenzofuran, and toluene, making it highly effective in oil refinery and marine wastewater. Additional engineered strains target BTEX compounds, synthetic dyes, and pharmaceuticals [63].

- General Adaptations: Genetic modifications also enhance resistance to salinity, pH fluctuations, and pollutant mixtures common in industrial effluents.

4.2.2. Algae (Microalgae)

- Nutrient and Metal Uptake: Microalgae such as Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and some species of moss are engineered using CRISPR/Cas9 and synthetic transcriptional activators to increase uptake of nitrogen, phosphorus, and metals.

- Hydrocarbon Resistance: Modified strains show improved tolerance to petroleum-related compounds and can express surfactants or enzymes for pollutant breakdown in oil and gas “produced water.”

4.2.3. Fungi

- Emerging Research Area: Although fungal GEMs are less mature compared to bacterial and algal systems, they are being investigated for consortium-based applications and degradation of complex chemical structures Table 2.

4.3. Applications and Deployment

- Heavy Metal Remediation: GEMs demonstrate effective removal of arsenic, mercury, cadmium, lead, and chromium under laboratory and pilot scale conditions.

- Degradation of Organic Pollutants: Engineered microbial consortia can degrade complex mixtures including hydrocarbons, phenols, dyes, and pharmaceutical compounds.

- Industrial and Municipal Wastewater: Field-tested algae and bacteria enhance nutrient recovery and metal detoxification, improving water reuse potential and ecological safety.

- Biosafety Concerns: Potential risks include gene escape, unintended ecological effects, and the need for robust containment strategies.

4.4. Challenges and Mitigation Strategies in the Deployment of Genetically Engineered Microorganisms

- Emergence of resistant traits: Engineered catabolic genes (on plasmids or mobile elements) could transfer to native microbes via HGT or confer unexpected traits. Phage-mediated transduction is a natural conduit for HGT in wastewater systems. Studies document phage carriage of antibiotic resistance and other genes in activated sludge, and experimental work shows phage dynamics can both suppress and facilitate community gene flow [68]. However, strategies involving the use of chromosomal integration, removable or disabled mobile genetic element sequences, designing synthetic gene clusters with minimized homology to environmental sequences, including genetic barcodes for tracking, and implementing multi-layered biological containment (auxotrophy for synthetic nutrients, kill-switches activated on escape) could effectively minimize these unexpected traits [69]. Regulatory frameworks for the release of GEMs into the environment vary by jurisdiction and are typically conservative; regulators require rigorous ecological risk assessment, monitoring plans, and contingency measures. Public concerns about GMOs in water treatment are real and can halt deployments. Early engagement with regulators and stakeholders, transparent risk assessments, phased testing (bench → closed piloting → monitored pilot plants with physical containment), independent environmental monitoring, and open data sharing can strategically ease out the commercial use of GEMs.

- Containment & operational controls. Physical escape routes (effluent discharge, aerosols, sludge reuse) require engineered control. Operational complexity increases when special nutrients or conditions are needed to maintain containment. Employing quality control checkpoints with biological safeguards (kill switches, CRISPR-based self-destruct circuits), engineering barriers (membrane filtration, UV or advanced oxidation post-treatment of effluent, sludge pasteurization), and continuous environmental DNA surveillance and qPCR/NGS tracking of engineered markers can provide an effective framework in managing the containment process.

- Ecological safety monitoring & metrics. Metrics to demonstrate safety should include: persistence and dispersal of engineered DNA/organism, changes in native community composition (16S/shotgun metagenomics), functional gene abundances (metagenomics/metatranscriptomics), and ecosystem endpoints (toxicity assays, bioindicator species). Pilot studies that couple removal performance with such monitoring strengthen the safety case

5. Integrated Omics Approaches in Water Bioremediation

5.1. Metagenomics

5.2. Metatranscriptomics

5.3. Metaproteomics

5.4. Metabolomics

5.5. Systems-Level Integration

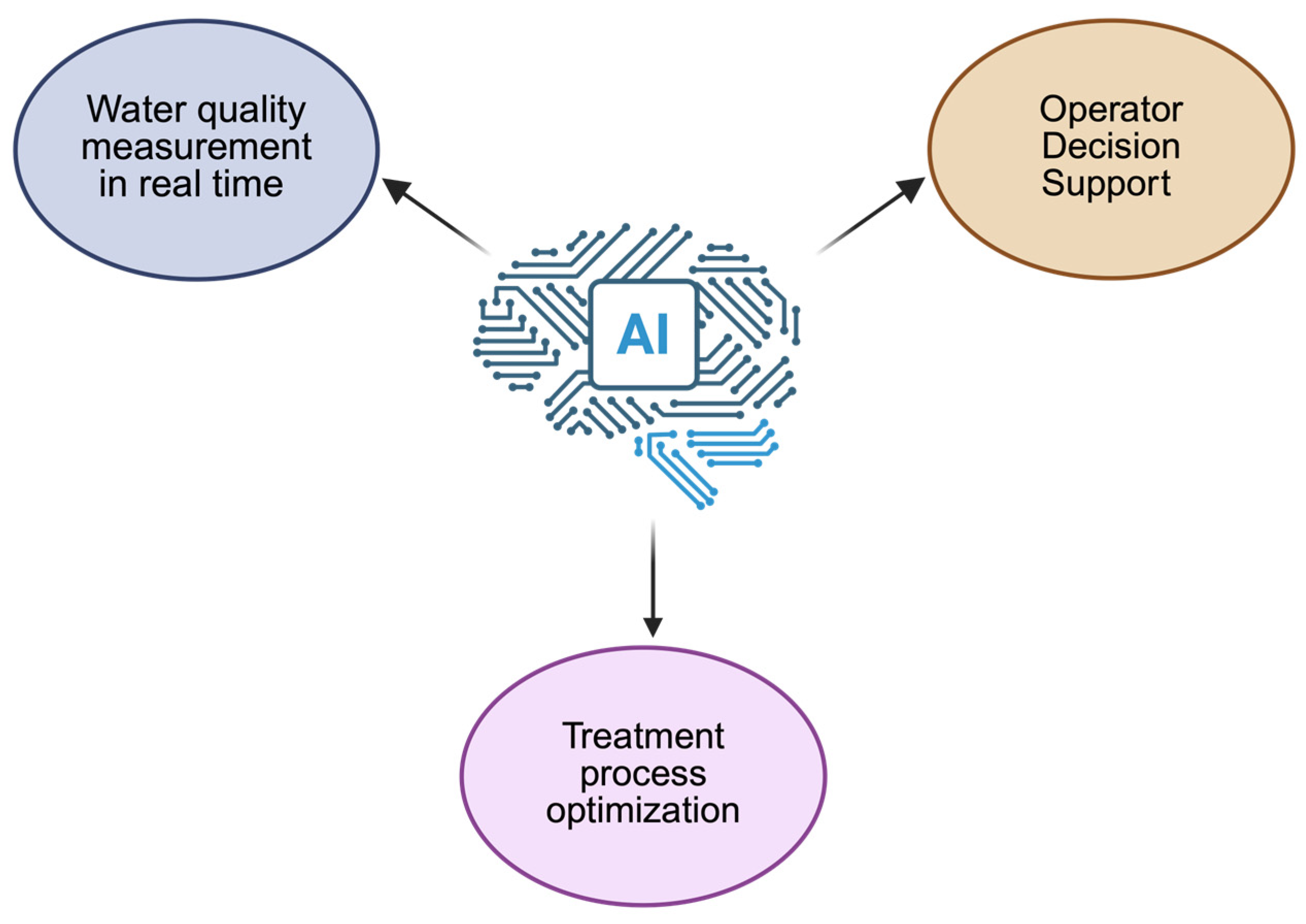

6. AI and Machine Learning (ML) in Omics-Guided Bioremediation

- Monitoring and prediction: ML models (Random Forest, SVM, Gradient Boosting) have been trained on multi-year WWTP datasets to predict COD and ammonia removal with >95% accuracy and anticipate process failures hours before occurrence.

- Process optimization: Deep learning architectures such as CNN–LSTM hybrids can continuously analyze pH, DO, and redox sensor data to predict aeration demand, cutting energy use by up to 20%.

- Microbial interaction modeling: Graph neural networks (GNNs) and correlation-based AI tools are used to infer microbial co-occurrence networks, identifying keystone species critical for system resilience.

- Case study: In one pilot-scale SBR, AI-driven control using an ML-optimized feedback algorithm improved nitrogen removal from 85% to 96% and reduced energy consumption by 18% over six months.

- Predictive biodegradation modeling: AI models trained on metagenomic features can predict the presence of xenobiotic-degrading genes across treatment stages with high precision (R2 > 0.9).

7. Nanopore Sequencing in Bioremediation

- On-site microbial surveillance: Real-time sequencing during treatment operations allows rapid detection of community shifts or pathogen emergence. For instance, MinION sequencing has tracked Nitrospira and Candidatus Accumulibacter dynamics in SBRs within 6 h, correlating taxa fluctuations with nutrient removal changes.

- Functional gene monitoring: Nanopore reads capture full-length catabolic operons and plasmids, improving detection of degradation pathways for hydrocarbons, pesticides, and pharmaceuticals.

- Adaptive control: Combined with ML algorithms, nanopore data can inform aeration and nutrient adjustments based on active microbial population signals.

- Case example: A recent field trial using MinION sequencing at an industrial WWTP enabled real-time detection of Comamonas testosteroni and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, prompting operational changes that improved phenol removal efficiency by 22%.

- Genomic resolution: Unlike short read platforms, nanopore sequencing resolves structural variants and mobile genetic elements, providing better insight into horizontal gene transfer.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Picinini-Zambelli, J.; Garcia, A.L.H.; Da Silva, J. Emerging pollutants in the aquatic environments: A review of genotoxic impacts. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2025, 795, 108519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ma, T.; Lan, Q.; Liu, B.; Liang, X. Single entity collision for inorganic water pollutants measurements: Insights and prospects. Water Res. 2024, 248, 120874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivaranjanee, R.; Senthil Kumar, P.; Chitra, B.; Rangasamy, G. A critical review on biochar for the removal of toxic pollutants from water environment. Chemosphere 2024, 360, 142382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanac, T.; Grgas, D.; Landeka Dragicevic, T. Xenobiotics-Division and Methods of Detection: A Review. J. Xenobiot. 2021, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Noh, J.; Khim, J.S. The Blue Economy and the United Nations’ sustainable development goals: Challenges and opportunities. Environ. Int. 2020, 137, 105528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevallos-Mendoza, J.; Amorim, C.G.; Rodriguez-Diaz, J.M.; Montenegro, M. Removal of Contaminants from Water by Membrane Filtration: A Review. Membranes 2022, 12, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.; Mavukkandy, M.; Giwa, A.; Elektorowicz, M.; Katsou, E.; Khelifi, O.; Naddeo, V.; Hasan, S. Recent developments in hazardous pollutants removal from wastewater and water reuse within a circular economy. Npj Clean. Water 2022, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massot, F.; Bernard, N.; Alvarez, L.M.M.; Martorell, M.M.; Mac Cormack, W.P.; Ruberto, L.A.M. Microbial associations for bioremediation. What does “microbial consortia” mean? Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 2283–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.U.; Hussain, N.; Sumrin, A.; Shahbaz, A.; Noor, S.; Bilal, M.; Aleya, L.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Microbial bioremediation strategies with wastewater treatment potentialities—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 818, 151754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azubuike, C.C.; Chikere, C.B.; Okpokwasili, G.C. Bioremediation techniques-classification based on site of application: Principles, advantages, limitations and prospects. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 32, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, J. Factors influencing residents’ acceptance (support) of remediation technologies. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 1369–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaid, S.; Mishra, T.; Bajaj, B.K. Ionic-liquid-mediated pretreatment and enzymatic saccharification of Prosopis sp. biomass in a consolidated bioprocess for potential bioethanol fuel production. Energy Ecol. Environ. 2018, 3, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzmarzick, M.J.; Taylor, D.K.; Fu, X.; McCutchan, A.L. Diversity and Niche of Archaea in Bioremediation. Archaea 2018, 2018, 3194108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kour, D.; Kaur, T.; Devi, R.; Yadav, A.; Singh, M.; Joshi, D.; Singh, J.; Suyal, D.C.; Kumar, A.; Rajput, V.D.; et al. Beneficial microbiomes for bioremediation of diverse contaminated environments for environmental sustainability: Present status and future challenges. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 24917–24939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, T.; Bhardwaj, V.; Ahuja, N.; Gadgil, P.; Ramdas, P.; Shukla, S.; Chande, A. Improved loss-of-function CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in human cells concomitant with inhibition of TGF-beta signaling. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2022, 28, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.B.; Shaikh, S.; Jain, K.R.; Desai, C.; Madamwar, D. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Sources, Toxicity, and Remediation Approaches. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 562813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglani, R.; Parveen, N.; Kumar, A.; Ansari, M.A.; Khanna, S.; Rawat, G.; Panda, A.K.; Bisht, S.S.; Upadhyay, J.; Ansari, M.N. Degradation of Xenobiotic Pollutants: An Environmentally Sustainable Approach. Metabolites 2022, 12, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.W.; Choi, Y.J. Extremophilic Microorganisms for the Treatment of Toxic Pollutants in the Environment. Molecules 2020, 25, 4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesheri, M.; Kanchan, S.; Mallik, B.; Mishra, T.; Ratna-Raj, R.; Chittoori, B.C.S.; Sinha, R.P. Envisioning Production of Alginates Through the Lens of Multi-Omics. In Multi-Omics in Biomedical Sciences and Environmental Sustainability; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 389–405. [Google Scholar]

- Mallik, B.; Mishra, T.; Dubey, P.; Kesheri, M.; Kanchan, S. Exploring the Secrets of Microbes: Unveiling the Hidden World Through Microbial Omics in Environment and Health; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 269–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, T.; Mallik, B.; Kesheri, M.; Kanchan, S. The Interplay of Gut Microbiome in Health and Diseases; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koley, S.; Jyoti, P.; Lingwan, M.; Allen, D.K. Isotopically nonstationary metabolic flux analysis of plants: Recent progress and future opportunities. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 1911–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, B.A.; Malhotra, H.; Papade, S.E.; Dhamale, T.; Ingale, O.P.; Kasarlawar, S.T.; Phale, P.S. Microbial degradation of contaminants of emerging concern: Metabolic, genetic and omics insights for enhanced bioremediation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1470522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.U.; Roy, H.; Islam, M.R.; Tahmid, M.; Fariha, A.; Mazumder, A.; Tasnim, N.; Pervez, M.N.; Cai, Y.; Naddeo, V.; et al. The Advancement in Membrane Bioreactor (MBR) Technology toward Sustainable Industrial Wastewater Management. Membranes 2023, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blessing, A.A.; Olateru, K. AI-driven optimization of bioremediation strategies for river pollution: A comprehensive review and future directions. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1504254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingwan, M.; Masakapalli, S.K. A robust method of extraction and GC-MS analysis of Monophenols exhibited UV-B mediated accumulation in Arabidopsis. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2022, 28, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modi, S.; Yadav, V.K.; Amari, A.; Osman, H.; Igwegbe, C.A.; Fulekar, M.H. Nanobioremediation: A bacterial consortium-zinc oxide nanoparticle-based approach for the removal of methylene blue dye from wastewater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 72641–72651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Guo, H.; Ma, F.; Shan, Z. Enhanced treatment of synthetic wastewater by bioaugmentation with a constructed consortium. Chemosphere 2023, 338, 139520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, B.; Pandey, P. Remediation of petroleum hydrocarbon contaminated soil using hydrocarbonoclastic rhizobacteria, applied through Azadirachta indica rhizosphere. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2022, 24, 1444–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Gong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, D.; Huang, X.; Yang, H. Bioaugmentation potential evaluation of a bacterial consortium composed of isolated Pseudomonas and Rhodococcus for degrading benzene, toluene and styrene in sludge and sewage. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 320, 124329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Cai, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Li, M.; Gong, H.; Yan, M. Isolation and Identification of Four Strains of Bacteria with Potential to Biodegrade Polyethylene and Polypropylene from Mangrove. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dong, X.; Wang, D.; Xie, Z. Biodeterioration of polyethylene by Bacillus cereus and Rhodococcus equi isolated from soil. Int. Microbiol. 2024, 27, 1795–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzella, C.; Macellaro, G.; Sannia, G.; Raganati, F.; Olivieri, G.; Marzocchella, A.; Schlosser, D.; Piscitelli, A. Exploitation of Trametes versicolor for bioremediation of endocrine disrupting chemicals in bioreactors. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, M.; da Fonseca, M.M.; de Carvalho, C.C. Bioaugmentation and biostimulation strategies to improve the effectiveness of bioremediation processes. Biodegradation 2011, 22, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, S.S.; Giri, B.S.; Basheer, F.; Izhar, T.; Ahmad, S.A.; Mumtaz, N. Enhancing sequencing batch reactors for efficient wastewater treatment across diverse applications: A comprehensive review. Environ. Res. 2024, 260, 119656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Peng, Y.; Huang, H.; Wang, S.; Ge, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z. Short- and long-term effects of temperature on partial nitrification in a sequencing batch reactor treating domestic wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 179, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelevina, A.; Gruzdev, E.; Berestovskaya, Y.; Dorofeev, A.; Nikolaev, Y.; Kallistova, A.; Beletsky, A.; Ravin, N.; Pimenov, N.; Mardanov, A. New insight into the granule formation in the reactor for enhanced biological phosphorus removal. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1297694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Chu, G.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, S.; She, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, C.; Guo, L.; Ji, J.; et al. Metagenomic analysis and nitrogen removal performance evaluation of activated sludge from a sequencing batch reactor under different salinities. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 323, 116213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Niftrik, L.; Jetten, M.S. Anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria: Unique microorganisms with exceptional properties. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 76, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos-Terrones, Y.A. A Review of the Strategic Use of Sodium Alginate Polymer in the Immobilization of Microorganisms for Water Recycling. Polymers 2024, 16, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Ortiz, E.J.; Gerlach, R.; Peyton, B.M.; Roberson, L.; Yeh, D.H. Biofilm reactors for the treatment of used water in space:potential, challenges, and future perspectives. Biofilm 2023, 6, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Islam, M.K.; Dev, S. Investigation of the performance of the combined moving bed bioreactor-membrane bioreactor (MBBR-MBR) for textile wastewater treatment. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentino, F.; Pavan, P.; Dosta, J. Editorial: Biofuels and Bioproducts From Anaerobic Processes: Anaerobic Membrane Bioreactors (AnMBRs). Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 694484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, A.; Jimenez-Benitez, A.; Gimenez, J.B.; Duran, F.; Ribes, J.; Serralta, J.; Ferrer, J.; Rogalla, F.; Seco, A. A semi-industrial scale AnMBR for municipal wastewater treatment at ambient temperature: Performance of the biological process. Water Res. 2022, 215, 118249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Nie, Y.; Wu, X.L. Predicting microbial community compositions in wastewater treatment plants using artificial neural networks. Microbiome 2023, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pila-Lacuta, S.; Pauccar, D.; Rojas-Vargas, J.; Rodriguez-Cruz, U.E.; Sierra, J.L.; Castelan-Sanchez, H.G.; Quispe-Ricalde, M.A. Isolation of a potentially arsenic-resistant Halomonas elongata strain (ml10562) from hypersaline systems in the Peruvian Andes, Cusco. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Ren, Y.; Bai, X.; Su, Y.; Han, J. Contributions of Beneficial Microorganisms in Soil Remediation and Quality Improvement of Medicinal Plants. Plants 2022, 11, 3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamze, A.; Zakaria, B.S.; Zaghloul, M.S.; Dhar, B.R.; Elbeshbishy, E. Comprehensive hydrothermal pretreatment of municipal sewage sludge: A systematic approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 361, 121194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, T.J.; Shewaramani, S.; Leahy, S.C.; Janssen, P.H.; Moon, C.D. Dynamics and genetic diversification of Escherichia coli during experimental adaptation to an anaerobic environment. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandolfo, E.; Duran-Wendt, D.; Martinez-Cuesta, R.; Montoya, M.; Carrera-Ruiz, L.; Vazquez-Arias, D.; Blanco-Romero, E.; Garrido-Sanz, D.; Redondo-Nieto, M.; Martin, M.; et al. Metagenomic analyses of a consortium for the bioremediation of hydrocarbons polluted soils. AMB Express 2024, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madoni, P. Protozoa in wastewater treatment processes: A minireview. Ital. J. Zool. 2011, 78, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pointing, S.B. Feasibility of bioremediation by white-rot fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 57, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Couto, S. Dye removal by immobilised fungi. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009, 27, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, A.R.; Mishra, T. Breaking Barriers: Non-Human Fungal Pathogens Crossing Kingdoms into Human Disease. Preprints 2025, 2025031385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, S.; Khanal, S.K.; Jasti, N.; Jin, B.; Pometto, A.L.; Van Leeuwen, J.H. Use of Filamentous Fungi for Wastewater Treatment and Production of High Value Fungal Byproducts: A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 40, 400–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.; Bhandari, G.; Turco, R.F.; Aminikhoei, Z.; Bhatt, K.; Simsek, H. Algae in wastewater treatment, mechanism, and application of biomass for production of value-added product. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 309, 119688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingwan, M. Metabolic modeling suggested noncanonical algal carbon concentrating mechanism in Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Plant Physiol. 2025, 197, kiaf019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibby, K.; Peccia, J. Identification of viral pathogen diversity in sewage sludge by metagenome analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 1945–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Yang, Q.; Feng, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, R.; Wang, R. The role of bacteriophages in facilitating the horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in municipal wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 2025, 268, 122776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.W.; Ho, H.C.; Yao, C.L.; Tseng, T.Y.; Kao, C.M.; Chen, S.C. Bioremediation potential of cadmium by recombinant Escherichia coli surface expressing metallothionein MTT5 from Tetrahymenathermophila. Chemosphere 2023, 310, 136850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhang, C.; Ren, Y.; Lin, J. Cd(II) and As(III) bioaccumulation by recombinant Escherichia coli expressing oligomeric human metallothioneins. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 185, 1605–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Chen, C.; Shen, Q.; Rosen, B.P.; Zhao, F.J. Genetically Engineering Bacillus subtilis with a Heat-Resistant Arsenite Methyltransferase for Bioremediation of Arsenic-Contaminated Organic Waste. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 6718–6724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, C.; Cui, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, C.; Yang, M.; Qu, L.; Li, Y.; Cai, Y.; et al. Bioremediation of complex organic pollutants by engineered Vibrio natriegens. Nature 2025, 642, 1024–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanien, A.; Saadaoui, I.; Schipper, K.; Al-Marri, S.; Dalgamouni, T.; Aouida, M.; Saeed, S.; Al-Jabri, H.M. Genetic engineering to enhance microalgal-based produced water treatment with emphasis on CRISPR/Cas9: A review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1104914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, A.; Singh, D.; Lingwan, M.; Yadukrishnan, P.; Masakapalli, S.K.; Datta, S. Light signaling and UV-B-mediated plant growth regulation. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 1270–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Cai, L.; Xu, B.; Li, X.; Qiu, W.; Fu, C.; Zheng, C. Sulfadiazine biodegradation by Phanerochaete chrysosporium: Mechanism and degradation product identification. Chemosphere 2019, 237, 124418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, T.; Ohno, H.; Ichinose, H.; Kawagishi, H.; Hirai, H. White-rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium metabolizes chloropyridinyl-type neonicotinoid insecticides by an N-dealkylation reaction catalyzed by two cytochrome P450s. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 402, 123831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodovich, T.; Shkoporov, A.N.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C. Phage-mediated horizontal gene transfer and its implications for the human gut microbiome. Gastroenterol Rep. 2022, 10, goac012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, M.T.; Kunjapur, A.M. Deployment of Engineered Microbes: Contributions to the Bioeconomy and Considerations for Biosecurity. Health Secur. 2020, 18, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, T.; Tiwari, P.B.; Rezaei, A.R.; Mallik, B.; Kanchan, S.; Kesheri, M. Disease Dynamics: Insights from Microbiome and Multi-Omics Analysis, 1st ed.; Kesheri, M., Kanchan, S., Häder, D.-P., Sinha, R.P., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 63–105. [Google Scholar]

- Crovadore, J.; Soljan, V.; Calmin, G.; Chablais, R.; Cochard, B.; Lefort, F. Metatranscriptomic and metagenomic description of the bacterial nitrogen metabolism in waste water wet oxidation effluents. Heliyon 2017, 3, e00427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Gong, H.; Liu, X.; Giwa, A.S.; Wang, K. Evaluation of bacterial association in methane generation pathways of an anaerobic digesting sludge via metagenomic sequencing. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Kushmaro, A.; Barak, H.; Poehlein, A.; Daniel, R.; Magert, H.J. Enhanced discovery of bacterial laccase-like multicopper oxidase through computer simulation and metagenomic analysis of industrial wastewater. FEBS Open Bio 2025, 15, 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhang, T.; Wang, W.; Liu, W.; Tang, H. Meta-omics assisted microbial gene and strain resources mining in contaminant environment. Eng. Life Sci. 2024, 24, 2300207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, L.K.; Chartrand, M.M.; Lacrampe-Couloume, G.; Lollar, B.S.; Spain, J.C.; Gossett, J.M. Proteomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal genes upregulated by cis-dichloroethene in Polaromonas sp. strain JS666. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 3733–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, A.; Turner, D.L.; Silva, M.A.; Salgueiro, C.A. New insights in uranium bioremediation by cytochromes of the bacterium Geotalea uraniireducens. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Hu, S.; Shi, S.; Ren, L.; Yan, W.; Zhao, H. Microbial diversity and metaproteomic analysis of activated sludge responses to naphthalene and anthracene exposure. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 22841–22852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Long, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Guo, K. Enhancement of microbiome management by machine learning for biological wastewater treatment. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 14, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, P.P.; Galodha, A.; Verma, V.K.; Singh, V.; Show, P.L.; Awasthi, M.K.; Lall, B.; Anees, S.; Pollmann, K.; Jain, R. Review on machine learning-based bioprocess optimization, monitoring, and control systems. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 370, 128523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Meng, D.; Yin, H.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y. Genome-resolved metagenomics provides insights into the ecological roles of the keystone taxa in heavy-metal-contaminated soils. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1203164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuffreda, L.; Rodriguez-Perez, H.; Flores, C. Nanopore sequencing and its application to the study of microbial communities. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1497–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkhof, L.J.; Dillon, K.P.; Häggblom, M.M.; McGuinness, L.R. Profiling bacterial communities by MinION sequencing of ribosomal operons. Microbiome 2017, 5, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Che, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, C.; Yin, X.; Deng, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhang, T. Rapid absolute quantification of pathogens and ARGs by nanopore sequencing. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 809, 152190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tool/Method | Microbial Systems | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Bacteria, Algae | Nutrient/metals uptake, hydrocarbon degradation |

| Gene Cluster Insertion | Bacteria (V. natriegens) | Multipathway degradation of hydrocarbons |

| Random/Directed Mutagenesis | Algae, Fungi | Enhanced stress tolerance, enzyme productivity |

| Synthetic Pathway Design | Bacteria, Algae, Fungi | Expression of nonnative degradation/accumulation enzymes |

| Engineered Organism/System | Genetic/Engineering Approach | Target Pollutant(s) | Reported Removal | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pseudomonas putida (PETtrophy engineering) | Genomic integration of tph operon (TA catabolism), secretion/surface display of PET hydrolases (LCC, HiC, IsPETase); host metabolic rewiring & ALE. | PET/PBAT (PET monomers: TA, EG) | Various degrees of plastic depolymerization in bench tests; engineered constructs enable PET hydrolase expression and monomer metabolism. | [53] |

| 2 | Engineered Dehalogenase/Oxygenase systems (various bacterial hosts) | Heterologous expression and directed evolution of dehalogenases/oxygenases. | PFAS analogues and halogenated organics | In vitro defluorination activity and enhanced turnover of model PFAS substrates. | [54] |

| 3 | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (engineered) | CRISPR/transgenic expression of mutant cytochrome P450 (e.g., BM3 MT variants) and other xenobiotic enzymes for enhanced degradation/bioassimilation. | Herbicides (Diuron) and selected pharmaceuticals | Enhanced Diuron transformation. | [54,55] |

| 4 | Engineered fungal laccases/enzyme-membrane reactors (Trametes, others) | Heterologous expression/promoter tuning/enzyme engineering (laccases, peroxidases) and immobilized enzyme membrane reactors (EMRs). | Azo dyes, complex textile colorants, phenolics | Continuous enzyme membrane reactor operation showed ~95% decolorization in some regimes and large reductions in mutagenicity. | [56] |

| 5 | Engineered (designed) consortia for hydrocarbon/PAH degradation | Rational consortium design (division of labor, metabolic coupling); synthetic ecology approaches to combine strains (often isolated + optimized) | Petroleum hydrocarbons, PAHs, mixed xenobiotics | Constructed consortia reported 74–95% removal of total alkanes or PAHs in enrichment/bench and pilot tests. | [57] |

| 6 | AnMBR (anaerobic membrane bioreactor) demonstration (biomass retention + engineered/selected anaerobes) | Reactor engineering to retain biomass (membranes), often coupled with microbial selection/adaptation; some pilot plants evaluate enriched/selected consortia. | Municipal wastewater organics (COD), nutrients; industrial high-strength wastewaters | Semi-industrial AnMBR: average COD removal 87.2 ± 6.1% during >600-day operation (40% of data > 90%); methane yields. | [58] |

| 7 | Genetic biocontainment/kill-switch systems (applied to engineered chassis) | CRISPR-based or multi-input kill switches, auxotrophy and environment-triggered containment circuits (chromosomal integration; minimized mobile elements). | N/A (containment technology to enable safe deployment of engineered microbes) | Demonstrated robust conditional killing/containment in controlled studies. | [59] |

| 8 | Enzymatic/directed-evolution PFAS studies & reviews (candidate dehalogenases) | Discovery and engineering of dehalogenases/reductive enzymes (growth-based selection, directed evolution, pathway mining) | PFAS (PFOA/model organofluorines) | In vitro and whole-cell assays report measurable defluorination or improved turnover of model substrates. | [60] |

| Omics Technique | Key Insights | Example Applications in Water Remediation |

|---|---|---|

| Metagenomics | Identifies microbial diversity (including unculturable microbes) and functional genes; reveals potential degradation pathways |

|

| Metatranscriptomics | Profiles active metabolic pathways and transcriptional responses of microbes under pollutant stress |

|

| Metaproteomics | Detects proteins directly involved in pollutant degradation; validates functional predictions |

|

| Metabolomics | Profiles intermediates and end-products of degradation; monitors metabolic fluxes and bottlenecks |

|

| Systems-Level Integration | Links diversity, function, enzymatic activity, and metabolites into a holistic framework; enhances precision and predictability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mishra, T.; Tiwari, P.B.; Kanchan, S.; Kesheri, M. Advances in Microbial Bioremediation for Effective Wastewater Treatment. Water 2025, 17, 3196. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223196

Mishra T, Tiwari PB, Kanchan S, Kesheri M. Advances in Microbial Bioremediation for Effective Wastewater Treatment. Water. 2025; 17(22):3196. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223196

Chicago/Turabian StyleMishra, Tarun, Pankaj Bharat Tiwari, Swarna Kanchan, and Minu Kesheri. 2025. "Advances in Microbial Bioremediation for Effective Wastewater Treatment" Water 17, no. 22: 3196. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223196

APA StyleMishra, T., Tiwari, P. B., Kanchan, S., & Kesheri, M. (2025). Advances in Microbial Bioremediation for Effective Wastewater Treatment. Water, 17(22), 3196. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223196