1. Introduction

As floods become more frequent and severe worldwide, the development of countermeasures to ensure the safety of local populations is urgently needed, and there is an increasing need for prompt and appropriate evacuation plans. Flood hazard maps, which help policymakers make effective evacuation decisions, are gaining recognition as regional populations become more aware of flood risks. However, when flooding occurs, the evacuee numbers recorded by local governments do not necessarily indicate whether the evacuation was efficiently conducted. Therefore, it is necessary to develop information systems that target those reluctant to evacuate [

1].

Implementing soft measures, such as flood hazard maps and warning systems, helps residents make evacuation decisions as they become more aware of flood hazard resources. However, evacuee numbers reported at evacuation centers indicate that there has been little progress in persuading residents to evacuate their homes. Existing research on the demographic groups who choose not to evacuate, or their reasons not to evacuate, is scarce. Information on evacuees’ attributes would be highly advantageous for medical personnel and other disaster relief workers [

2].

Many previous studies have estimated evacuee populations using satellite imagery and census data [

3,

4]. However, these approaches primarily provide static snapshots—such as nighttime population distributions—and thus fail to capture real-time movements. With the advent of Mobile Spatial Statistics (MSSs), which ensure user confidentiality, dynamic population data have become available and are now used to study evacuation behaviors in actual disaster contexts [

5]. Mobile phone–based data enable high-resolution population grids and are increasingly applied across various disciplines, including disaster response and transportation research [

6].

Various studies on evacuation behavior during flooding have examined how prior disaster experiences influence residents’ decision-making processes [

7,

8,

9,

10]. An agent-based model incorporating flood experience has been used to analyze the acquisition of evacuation decision criteria through reinforcement learning, demonstrating that repeated experiences influence adaptive decision-making [

11,

12]. Another study investigated flood evacuation situations through a questionnaire survey, providing valuable insights into residents’ actual responses during flood events [

13]. Additionally, the utilization of volunteered geographic information—such as data from X (formerly Twitter)—has been increasingly promoted in this field, underscoring the usefulness of crowdsourced data for enhancing real-time situational awareness [

14]. Several studies have also assessed evacuation behavior from an economic perspective, highlighting how economic valuation and willingness-to-pay approaches can inform flood risk reduction strategies [

15,

16].

Globally, considerable efforts have been made to understand population demographics using mobile phone tower data [

17]. One study utilized mobile spatial statistical data to estimate population changes during disasters, demonstrating the feasibility of capturing high-resolution spatiotemporal population shifts [

18]. Another study analyzed dynamic population movements of evacuees by gender and age before and after an earthquake, revealing demographic differences in evacuation behavior [

4]. Population dynamics during earthquakes have also been studied [

5]. For instance, research on the Kumamoto earthquake examined the distribution of relief supplies to numerous undesignated shelters that emerged when official evacuation centers reached capacity, emphasizing the importance of recognizing informal evacuation trends [

19]. Furthermore, agent-based models have been used to simulate evacuation behavior, although their validation in real-world disaster settings remains challenging [

20]. Demographic data during evacuation are particularly difficult to obtain; previous studies have relied on evacuation center user lists or post-disaster questionnaires [

21], which are often constrained by low response rates and the inability to capture evacuees in unofficial locations.

When considering natural disasters, flooding is a phenomenon in which residents evacuate more gradually, according to the degree of perceived flood risk from information that they receive. Flooding emergencies differ from other natural disasters, such as earthquakes, because populations most often do not require long-term evacuation. Consequently, we expect significant differences in gender and generational trends between these two types of disasters. Floods differ from earthquakes and tsunamis in that evacuations may occur in response to progressively worsening conditions, sometimes with some advance warning. Nevertheless, flooding is not always predictable, particularly in the case of flash floods [

22].

Accordingly, the objectives of this study are to (1) quantitatively clarify evacuee demographics of gender and age range, and identify target populations that should be encouraged to evacuate in similar geographical locations in the northeastern part of Japan—before and at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic; and (2) establish a method to quantitatively evaluate the evacuation behavior of residents in any given area, using a flood hazard-based evacuation curve.

2. Materials and Methods

For this study, we analyzed MSS to identify evacuation time trends among the population in flood zone areas that were being evacuated.

2.1. Datasets

The study employed hourly dynamic MSS, provided by the Japanese mobile phone operator NTT Docomo [

23]. The number of mobile phones in each area was regularly monitored at base stations, and NTT Docomo estimated the population using basic resident ledger data managed by municipalities. People whose mobile carriers use non-Docomo mobile phones were considered using NTT DOCOMO’s mobile phone penetration rate. Data were then de-identified with confidentiality processing. The data did not include mobile phone users under the age of 15 or over 80. The spatial resolution of the data was 500 m, making it possible to determine the population for each grid cell by age and gender.

2.2. Study Area

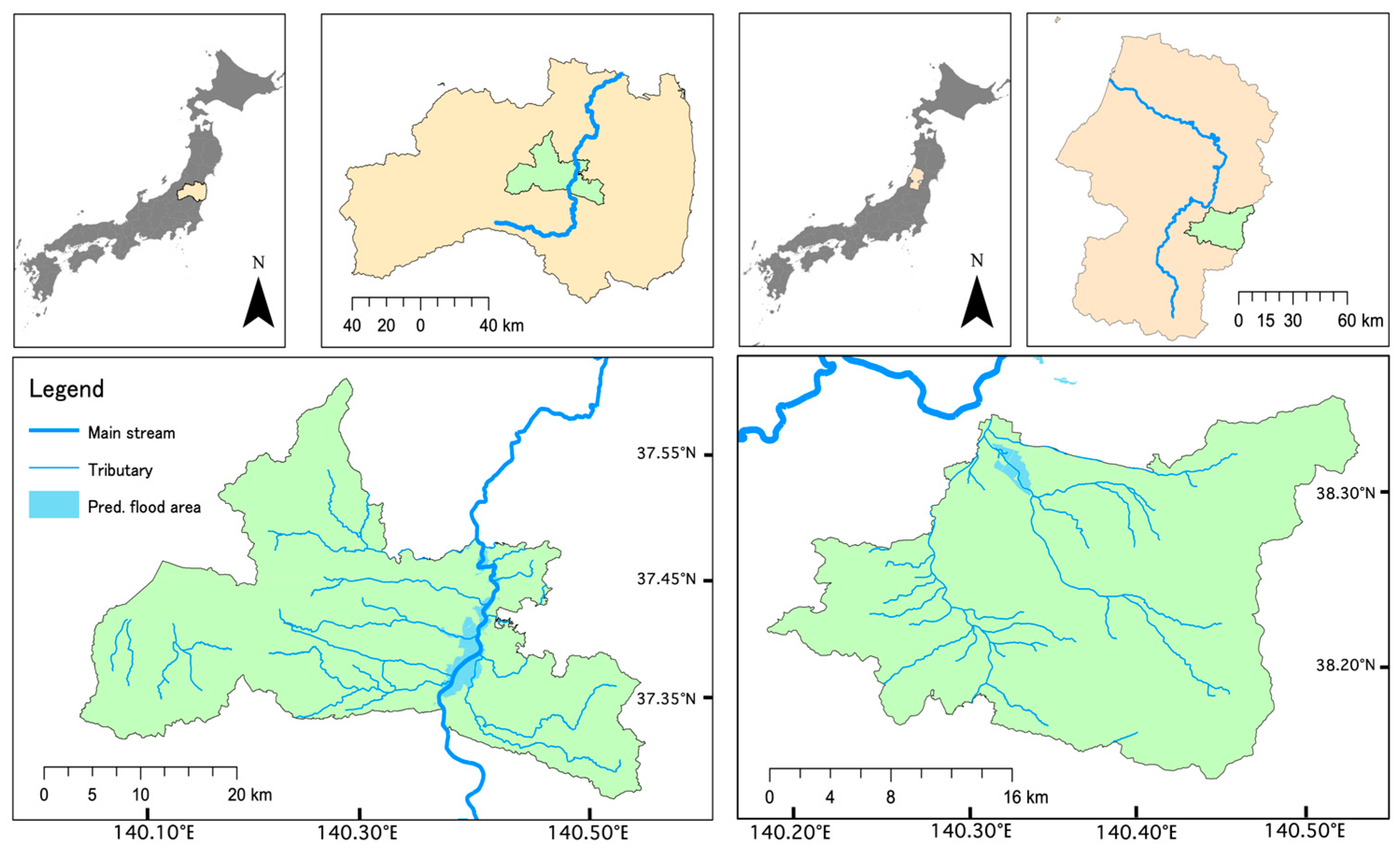

The study areas were Koriyama City in Fukushima prefecture (population 350,000) and Yamagata City in Yamagata prefecture (population 250,000) (

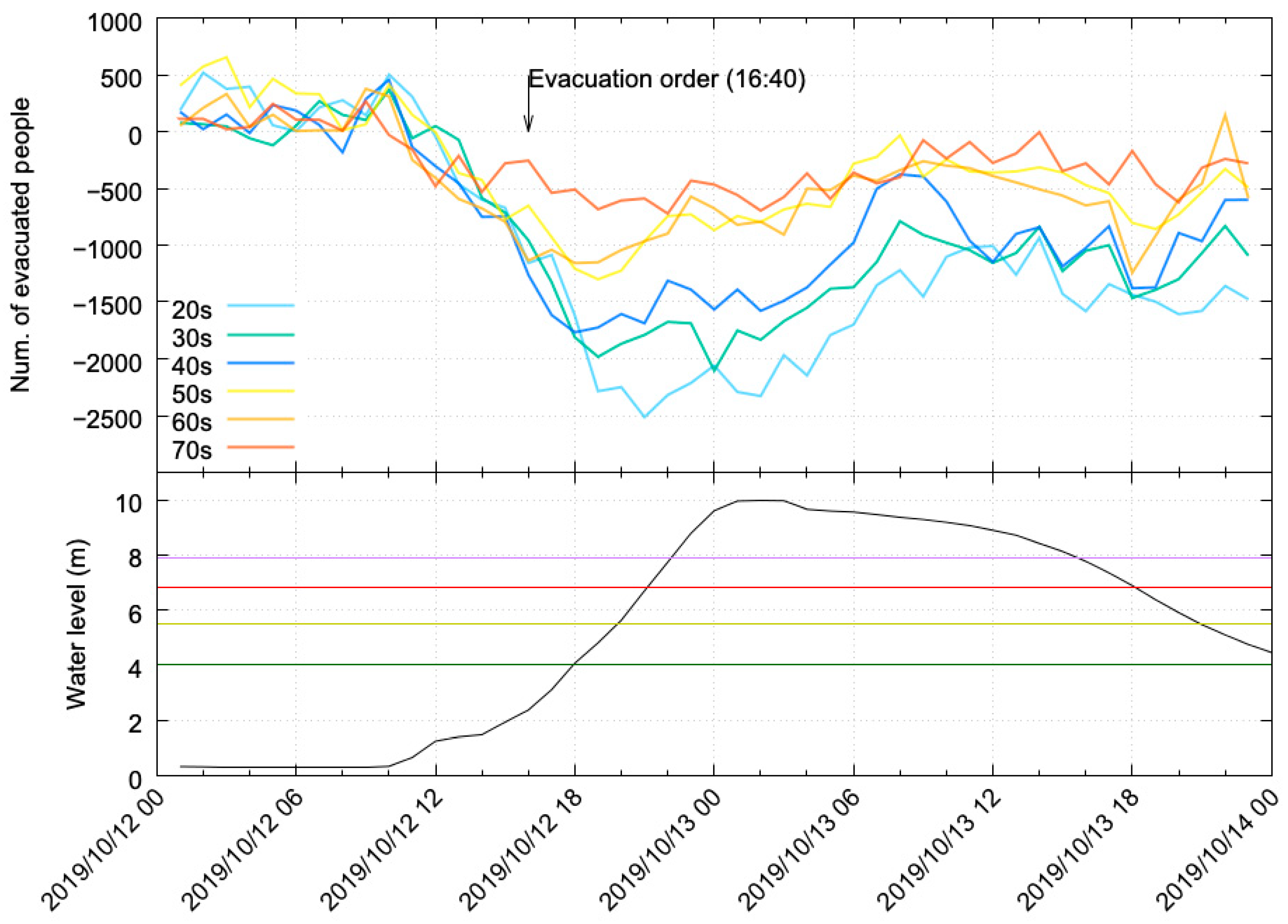

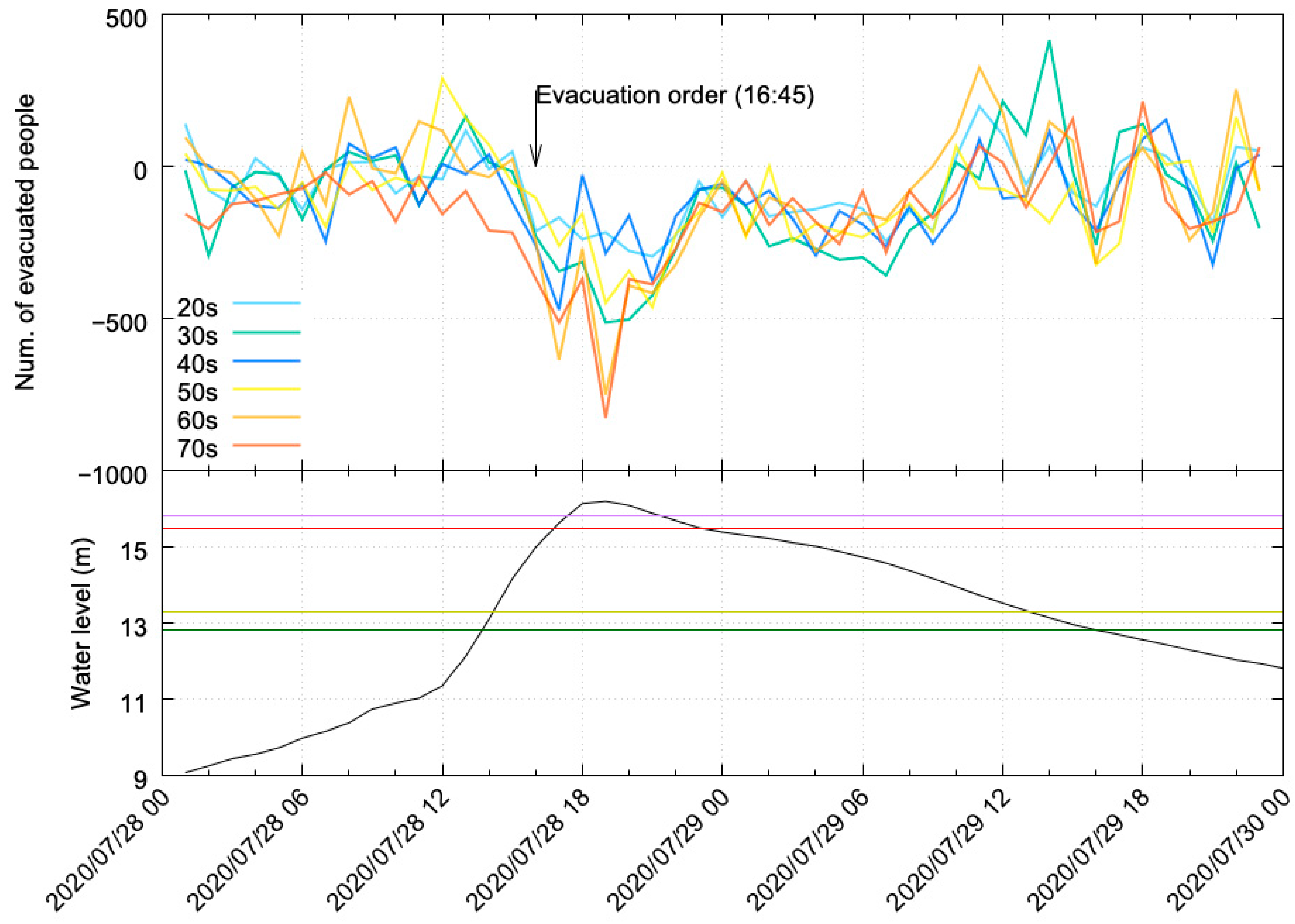

Figure 1). Koriyama experienced a typhoon on 13 October 2019 (before the pandemic), and Yamagata was affected by torrential rains on 28 July 2020—at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. In both events, flood risk increased during the evening, and evacuation orders were issued around 16:00. The temporal scale of these two events was approximately the same.

The 2019 East Japan Typhoon (Typhoon Hagibis) caused extensive river flooding after making landfall on the Izu Peninsula shortly before 19:00 on 12 October 2019, severely affecting the Kanto and Tohoku regions, including Koriyama.

The rainy season in early July 2020 brought record-breaking rainfall to the Kyushu region, resulting in large-scale river flooding, landslides, and other extensive damage [

24]. Torrential rains associated with the seasonal rain front fell in the Yamagata region on July 27 and 28, causing extensive damage in Yamagata [

25]. In the middle reaches of the Mogami River, Murayama City and Higashine City experienced river flooding from branch rivers. In Oishida Town, some areas were flooded due to overflow from the main branch of the Mogami River.

We selected these two municipalities because flooding is likely in these regions, and river-level information can be obtained from nearby municipalities. Extensive data on river water levels and rainfall have been accumulated, covering the period required to analyze both the 2018 typhoon and the 2020 torrential rainfall events. A key difference between the two study areas is that the Koriyama typhoon occurred before the COVID-19 pandemic, whereas the Yamagata torrential rains took place during it. This distinction is relevant because the perceived risk of infection may have influenced evacuation decisions and shelter use, factors directly related to the demographic evacuation patterns analyzed in this study. Notably, no increase in COVID-19–positive cases was observed in Yamagata Prefecture following the event, suggesting that evacuees likely took appropriate precautions against infection. This context is essential for interpreting the population movement data recorded during the flood. It was assumed that the typhoon evacuees were aware of the risk of infection in the shelters and took relevant precautions. A part of the urban area of Koriyama was within the predicted flooding area and sustained damage, while the city of Yamagata itself was spared from flooding. The water levels recorded at the Akutsu observatory station in Koriyama and the Nagasaki observatory station in Yamagata were compared. The two municipalities were divided into tertiary mesh grids (1000 m), and real-time population changes within the predicted flooded areas (pale blue regions in

Figure 1) were estimated. Predicted flood areas were obtained from hazard maps provided by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT), which delineate inundation zones under severe flood scenarios.

2.3. Demographics of the Evacuated Populations

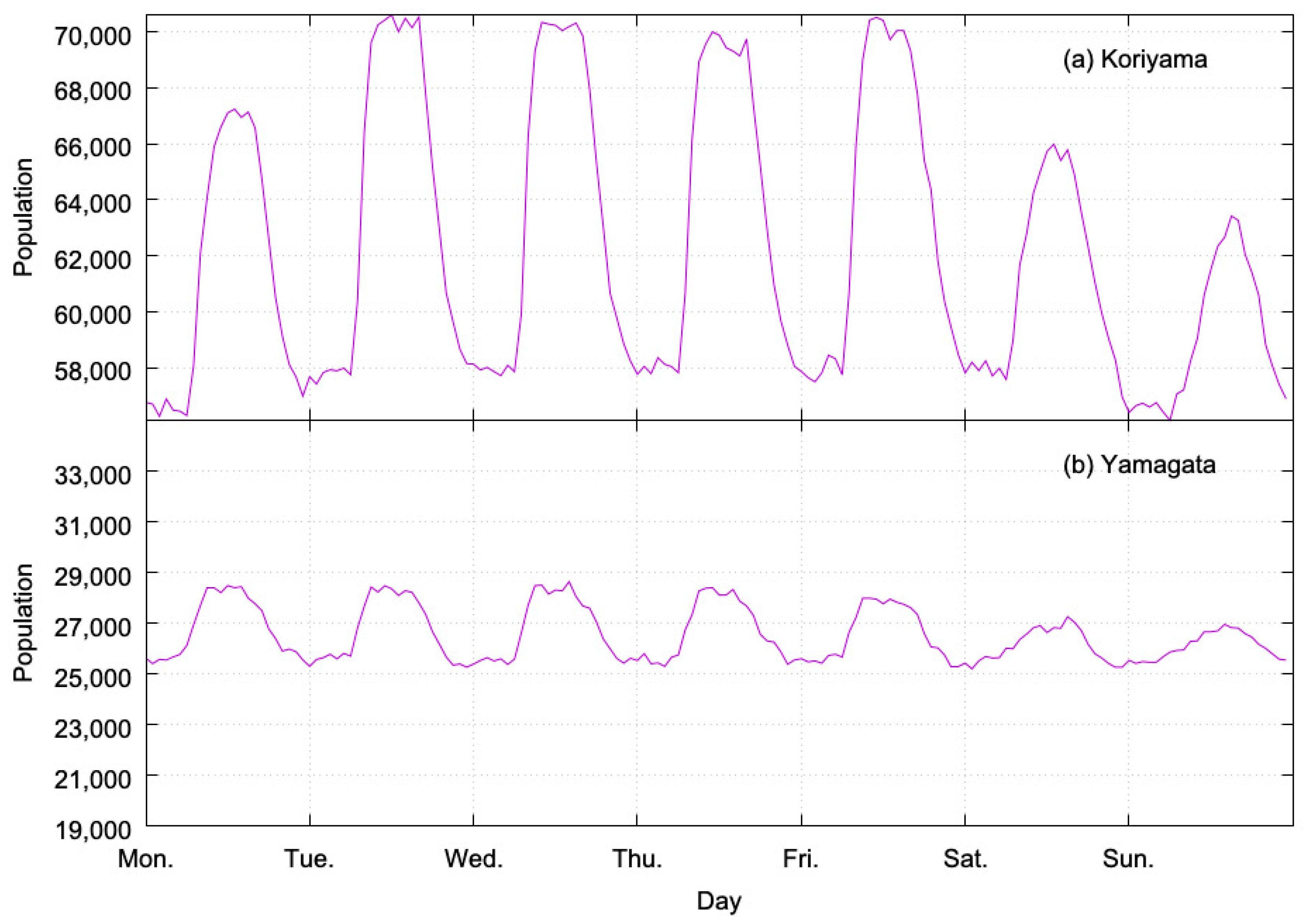

Given the day-night and day-of-week periodicity in population fluctuations and the fact that this cycle varies between weekdays and weekends, representative diurnal population patterns for weekdays and weekends were calculated using population cycles observed during the five weeks preceding the flood as below:

Here,

Pave = base line population in a week,

i = week,

j = day of the week,

k = proper time, and

l week (five weeks) are used as the sample. The average values of

i,

j, and

k are calculated as the standard population not experiencing any particular situation. The populations in the flood-estimated areas differ because of the size of the two municipalities.

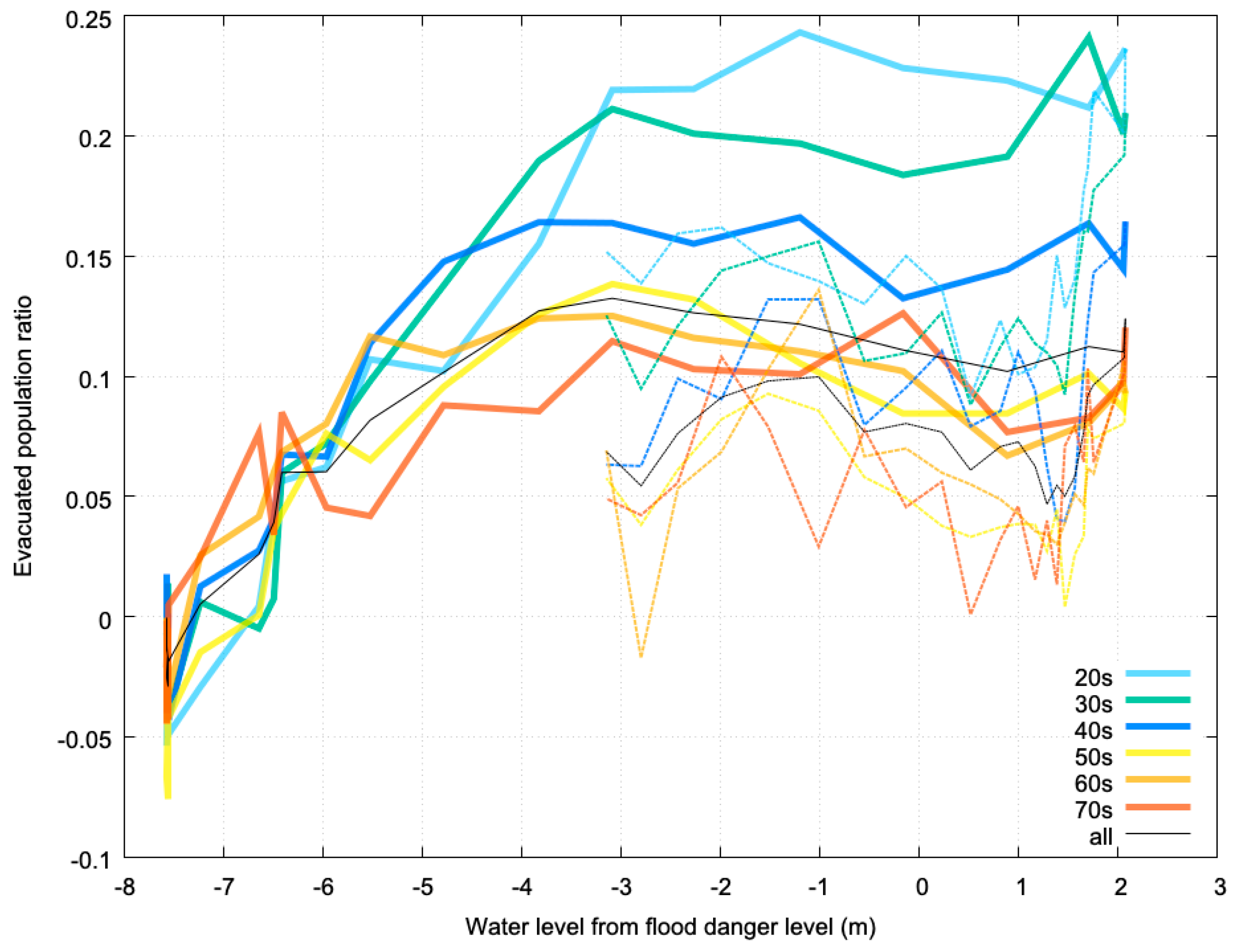

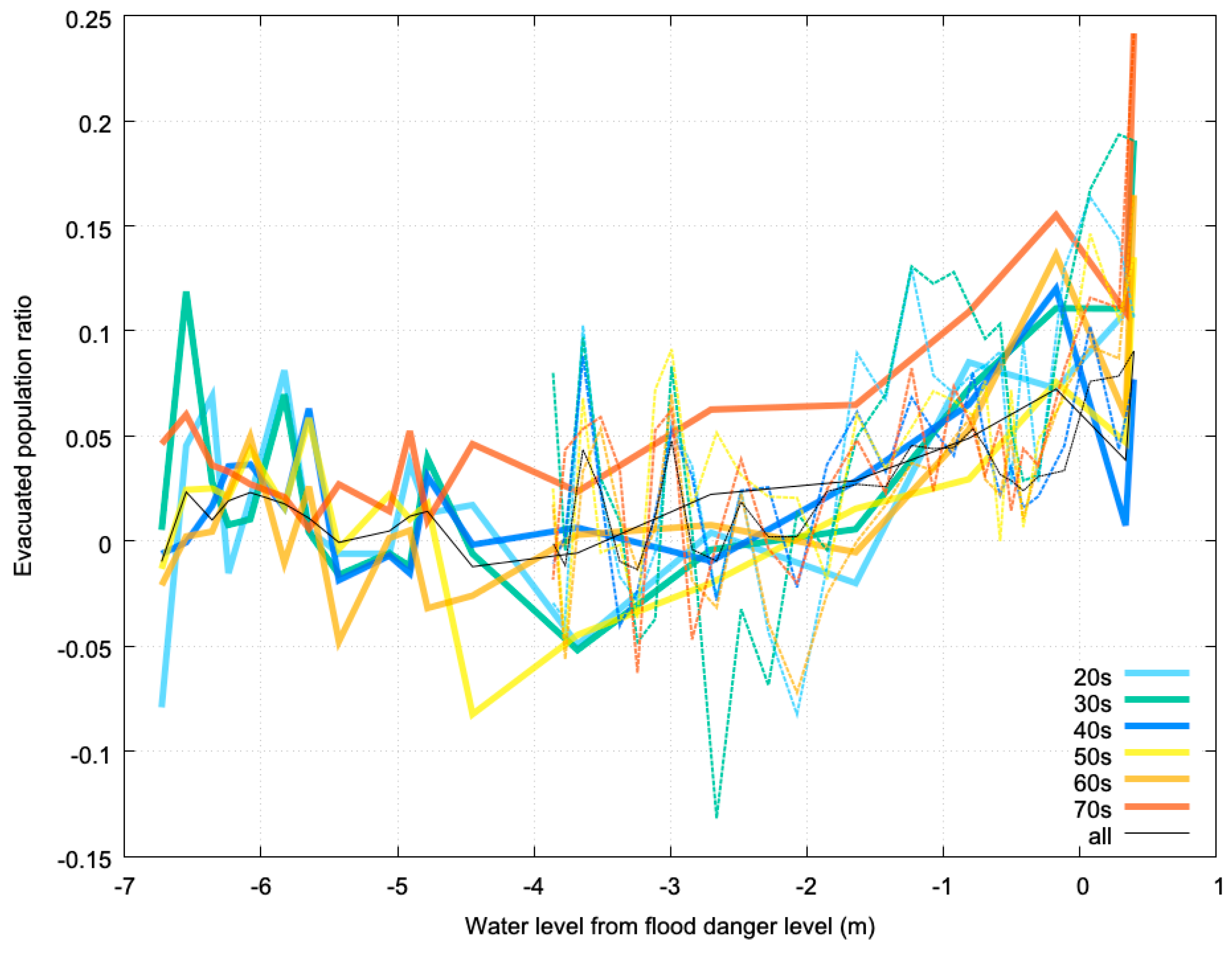

Figure 2 presents the baseline weekly population cycle, constructed from average day-of-week and hourly variations observed during the five weeks preceding the flood. This baseline serves as a reference pattern under non-flood conditions, against which evacuation-related changes were evaluated.

To estimate the typical population in a week, we calculated the average population at the same time on the same day for five weeks.

Using the estimated typical population in a week, we estimated the evacuation population as below:

Here, Pevac = evacuated population and P = population at that time. The difference from the average is defined as the evacuated population.

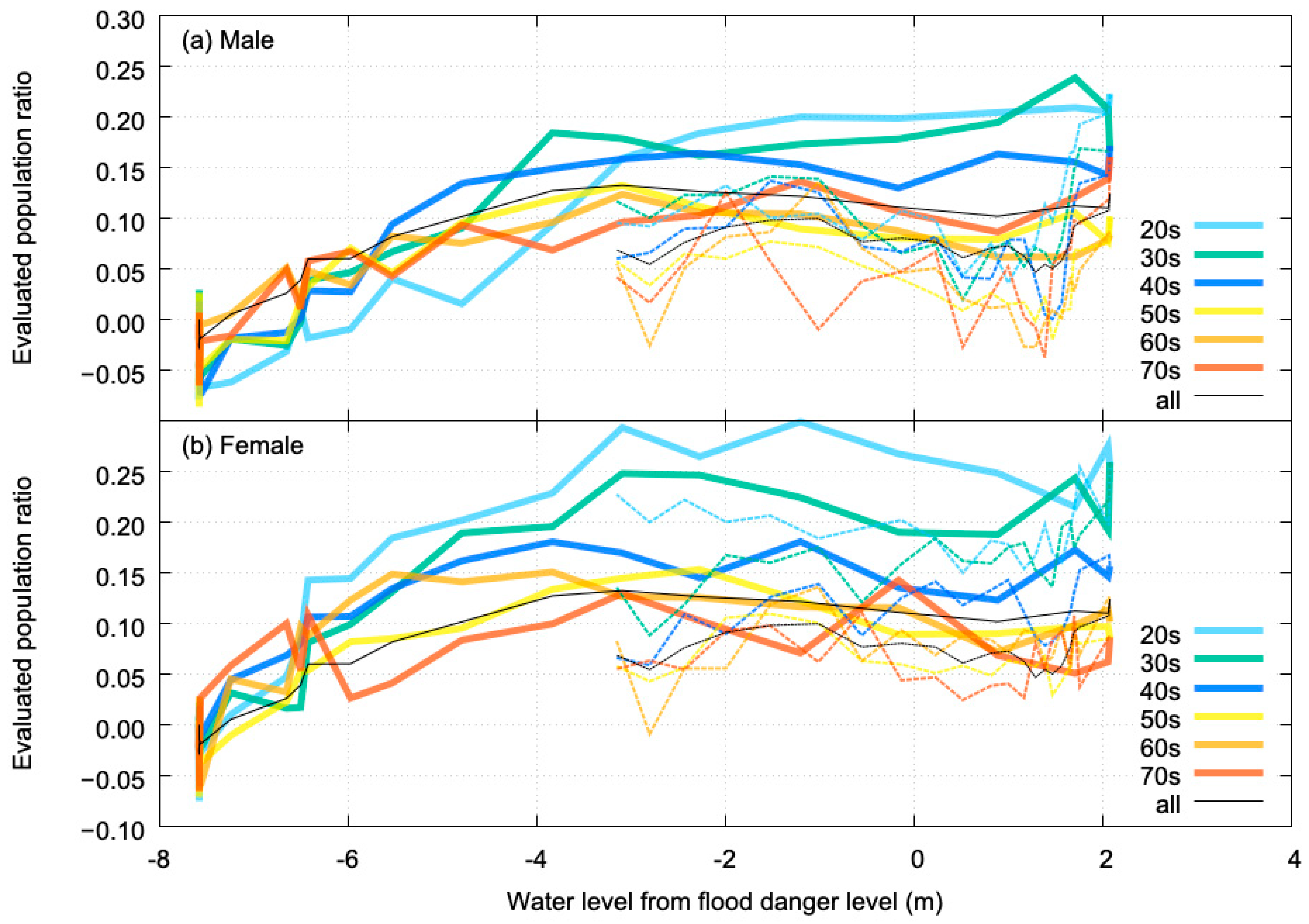

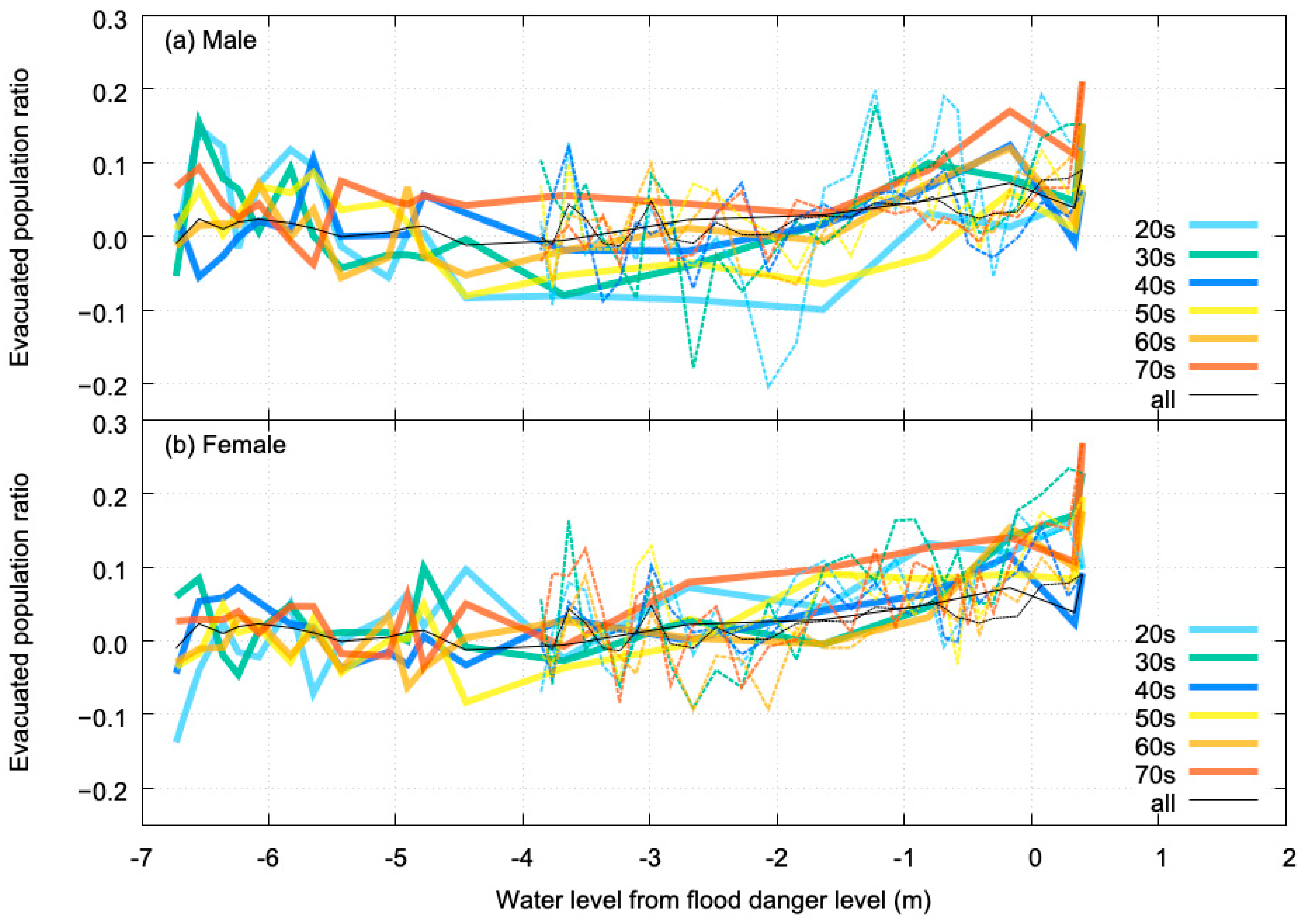

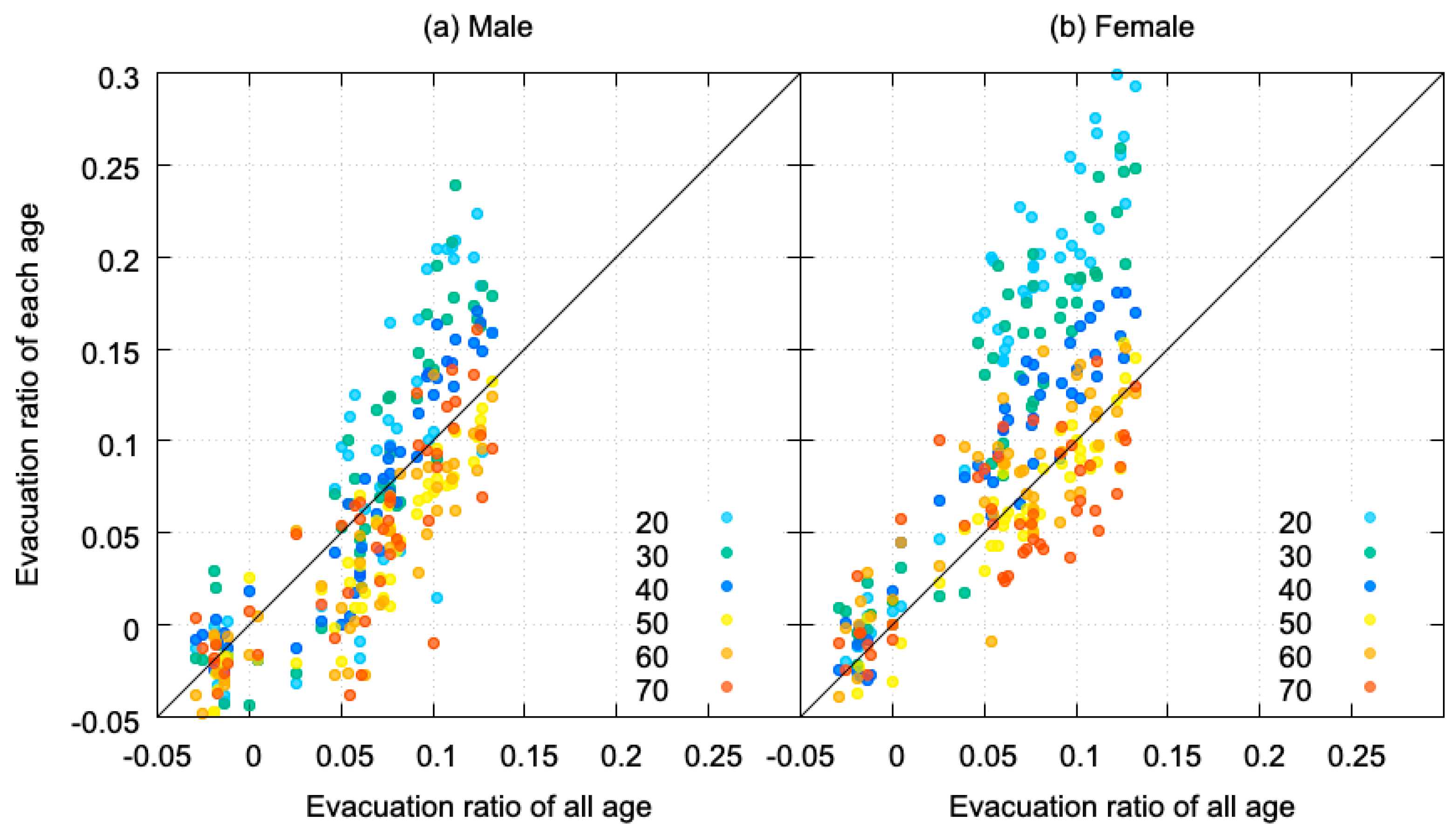

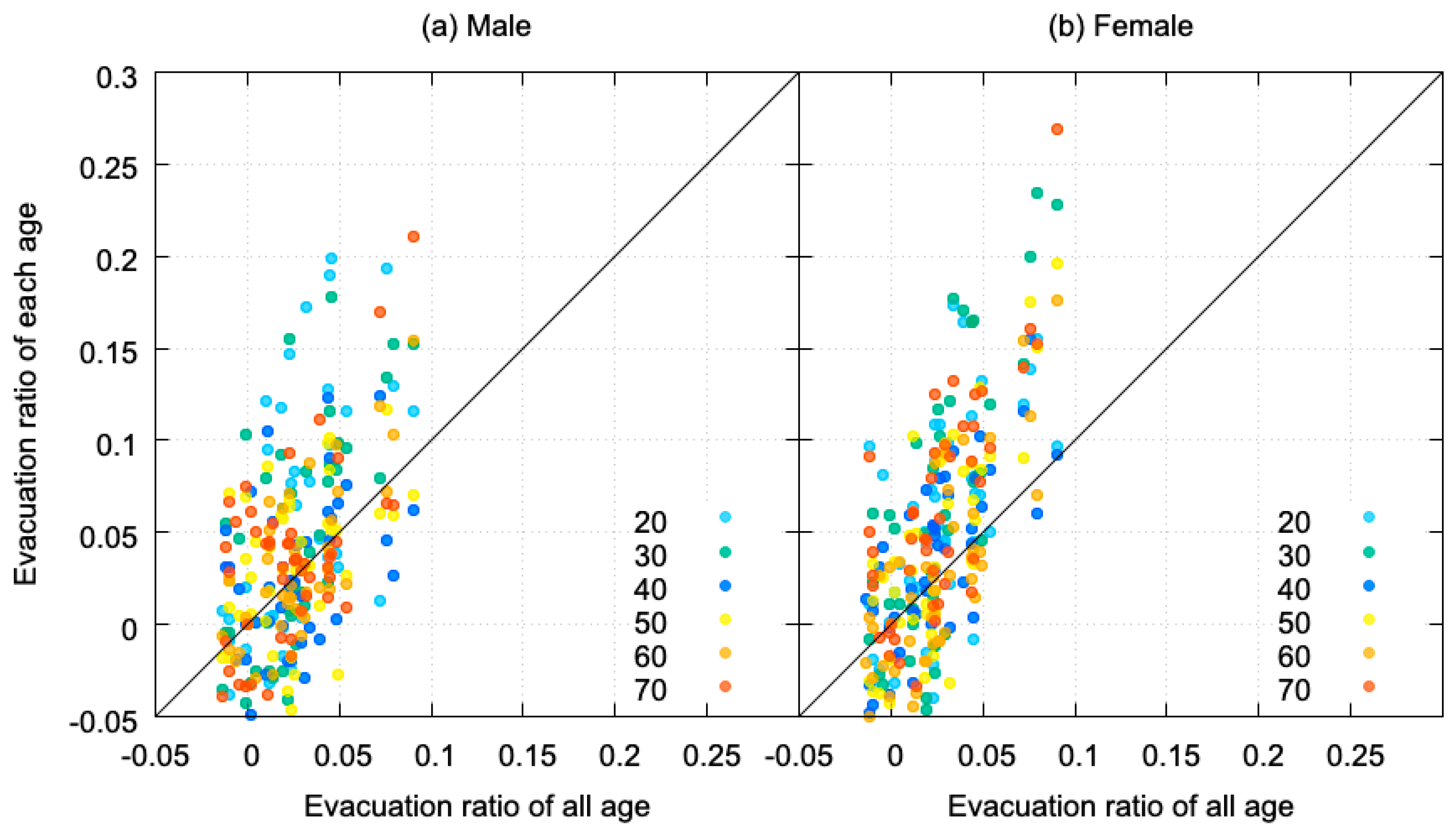

To quantitatively assess gender differences in evacuation, we focused on evacuated population ratios during the peak evacuation period and calculated the multiplier for each age group and gender relative to the overall evacuated population ratio, using the following formula:

Here, i = age group, PRRi = relative evacuated population ratio at the evacuation peak, PRi = peak evacuated population ratio for age group i, and PRall = peak overall evacuated population ratio.

4. Discussion

4.1. Novelty and Key Findings

This study is novel because it clarifies evacuation dynamics on a finer time scale than, for example, the monthly analysis conducted for earthquakes by Hada et al. [

4]. The substantially higher evacuation rate among women in their 30s was also reported by Hada et al. [

3], and a similar trend was observed in the present study. As Hada et al. [

4] speculated, it is likely that the child-rearing generation with infants and toddlers might have actively engaged in evacuation behavior. In addition, because wide-area evacuation depends on transportation availability, the relationship between generation and evacuation rates must be further analyzed [

26]. For example, targeted communication strategies such as early warning messages via social media or mobile applications could be designed to better reach the child-rearing demographic, particularly women in their 30s who demonstrated proactive evacuation behavior. In contrast, tailored evacuation support programs for the older adults—such as neighborhood-based assistance networks or pre-registered evacuation transportation services—may mitigate delayed responses in future disasters.

4.2. Limitations of the Study

This study used MSS to capture the evacuation behavior of populations in two mid-sized urban cities in Japan, as flooding risks increased. However, we acknowledge that several key factors influencing evacuation behavior—such as flood severity, timing of evacuation orders, infrastructure availability, and prior disaster experience—were not systematically isolated or quantified due to limitations in the available data. Future studies should aim to incorporate such variables using multivariate approaches to better disentangle their effects.

Moreover, this study did not capture vertical evacuation or shelter-in-place behavior, which are common in urban flood scenarios. Since MSS data reflect location movement patterns, individuals who evacuated vertically within their residence or remained at home may have been interpreted as non-evacuees. This limitation should be considered when interpreting evacuation rates, especially in densely built urban areas where such behaviors are prevalent.

It should be noted that MSS data are available with a temporal resolution of 30 min and are not provided in real time. This latency imposes limitations on the real-time applicability of the data for immediate emergency response or early warning systems. Nevertheless, the objective of this study is not to enable real-time evacuation guidance, but rather to evaluate post-event evacuation behavior patterns across demographics for planning and policy purposes. Future research and collaboration with data providers may enable reduced latency or real-time data access, which would enhance the utility of MSS for operational disaster management.

4.3. Generalisability of the Findings

Although this study examines only two flood events in Japan, the findings may not be generalizable to regions with different geographical, climatic, socio-economic, or institutional contexts. Therefore, caution should be exercised in interpreting the gender- or age-related evacuation tendencies as universal patterns. Future research should aim to validate this methodology in a variety of international contexts—such as densely populated Asian cities, flood-prone low-lying European regions, or urban peripheries in developing countries—to assess its broader applicability and robustness in diverse disaster scenarios.

4.4. Methodological and Practical Implications

Despite its limited scope, the methodology developed in this study is novel in two key respects. First, unlike previous disaster studies that typically analyzed evacuation behavior at monthly or daily intervals, our approach utilizes MSS data with a 30 min temporal resolution, allowing the examination of evacuation dynamics at a much finer time scale. Second, by disaggregating the data by both generation and gender, we systematically captured demographic differences in evacuation patterns that have not been fully explored in previous flood research. These methodological advances make the framework innovative and provide a foundation for applying it to other regions and disaster types, potentially revealing broader patterns in evacuation behavior.

This study focused on evacuation behaviors during individual flood events; however, longitudinal analysis across multiple disasters would provide valuable insights into how repeated hazard exposure and shifts in societal risk perception influence evacuation decisions over time. Since MSS only became publicly available in October 2013, the history of using MSS for evacuation behavior analysis remains relatively short. Nonetheless, accumulating evacuation data across recurrent flood events will be essential for discussing how evacuation behavior by age group evolves in response to repeated disasters and changing public awareness.

4.5. Future Research Directions

Among the results obtained in this study, the most significant difference in the two areas was the start time of evacuation behavior, considering the river water level. In addition, how agencies disseminate information differs between flooding by a typhoon and flooding by torrential rain; a direct comparison, therefore, has limitations. Nevertheless, there is a need for future research on the timing of evacuation orders from municipal governments and their impacts on populations. As mentioned by Alias [

21], evacuation behavior of each generation and gender may be highly influenced by the media through which they receive information about disasters. Further research is needed on the relationship between the means of obtaining information and the timing of evacuation. The results of the current study suggest that the younger generation actively collects information when the accuracy of disaster risk prediction is high, like in Koriyama. Regarding the older adults who may delay their evacuation, as observed in some parts of this study, it may be necessary to consider an evacuation plan that captures the time required for evacuation [

27]. Especially in flash flood-prone countries such as Japan, early evacuation is preferred, before the floods become high-velocity currents [

28].

4.6. Generational Differences and Future Research Directions

Once detailed data on evacuation behavior by age group and gender are accumulated, it may be possible to determine whether there is a suppressive effect on evacuation behavior during an infectious disease epidemic [

29,

30,

31]. The COVID-19 pandemic may have created anxiety regarding the crowdedness in evacuation centers during the 2020 Yamagata rain disaster; it is therefore possible that people hesitated to start evacuation and tried to return as soon as possible. However, people in Koriyama were more likely to not return home for a longer time, likely owing to the severity of the flooding itself and because there was no infectious disease outbreak. To confirm changes in evacuation behavior during a flooding event that coincides with a spike in COVID-19 cases in the area, accumulation of data on comparable flood events of the same magnitude in the presence or absence of COVID-19 outbreaks—longitudinally or cross-sectionally—is necessary.

Interestingly, this study found contrasting evacuation patterns among older adults in the two cities: While evacuation rates among those aged 60 and above were relatively low in Koriyama, Yamagata showed a trend of earlier and more active evacuation among the same age group. Several factors may contribute to the discrepancy in evacuation patterns of older adults between the two cities. First, the nature of the flood events differed: The Koriyama event was driven by typhoon-induced flooding. Second, one possible explanation is that the Yamagata event was characterized by localized torrential rainfall, and the perceived severity and timing of such events may have influenced decision-making processes differently across age groups. Another contributing factor could be differences in risk communication strategies. In Yamagata, real-time local media and community networks may have played a stronger role in disseminating evacuation alerts to older residents, who often rely more heavily on traditional information sources. Third, sociocultural factors, such as community cohesion and prior disaster experience, might have affected evacuation readiness. For example, Yamagata’s higher community-based disaster awareness programs or past flood experiences may have heightened preparedness among older adults. Further research is needed to examine these factors systematically through surveys or interviews in order to clarify how context-specific conditions influence age-based evacuation behaviors.