Abstract

Activated sludge microorganisms in sewage treatment plants are crucial for controlling water pollution and protecting public health and the ecological environment. Activated sludge must have biodegradation, easy sedimentation, and separation functions. Filamentous bacteria play an essential role in floc formation and structure. However, low temperature, low load and low dissolved oxygen (DO) will destroy the balance between beneficial structural action and harmful overgrowth. In this study, the high-throughput sequencing (HTS) dataset of 16s rRNA gene sequence V3–V4 amplicons from 30 activated sludge samples from the Chuanhu Sewage Treatment Plant in Changchun was analyzed to investigate the abundance distribution of filamentous bacteria and further determine the main operating parameters and environmental factors. The experimental results showed that the filamentous bacterial community accounted for a large part of the entire microbial community, with the total filamentous bacterial percentage in each sample ranging from 7.32% to 56.81%, with large fluctuations in abundance and consistent with the SVI value. Although most of them were in flocs, they occasionally caused sedimentation problems when the water temperature was low. With 14 species of filamentous bacteria detected, the population structure of filamentous bacteria in the thermophilic, variable-temperature and low-temperature periods was universal and specific. The groups with a detection frequency of 100%, high abundance, and significant fluctuations in distribution were Microthrix parvicella and Nostocoida limicola I. The Pearson correlation analysis showed that the total abundance of filamentous bacteria and the fluctuation distribution of dominant filamentous bacteria abundance were significantly correlated with water temperature, sludge load, sludge age, and mixed liquid suspended solids (MLSS).

1. Introduction

Most cities use activated sludge processes to treat wastewater and continue to promote its application in public health in other parts of the world [1]. As the world’s most extensive biological application technology, activated sludge contains highly complex microbial communities essential in pollutant decomposition and removal. Using molecular biology and microbial informatics techniques, it has been revealed that its diversity and structure directly impact wastewater treatment performance (such as nutrient removal, sludge bulking, etc.) [2]. The basic process of activated sludge is to use a mixed microbial population of ordinary heterotrophic microorganisms, ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, nitrite-oxidizing bacteria, etc., to remove carbon and nitrifying ammonia under aerobic conditions. A more advanced configuration is to remove nitrate through denitrifying bacteria and phosphate through polyphosphate-accumulating bacteria. The filamentous bacteria—another critical group of bacteria in activated sludge—have been extensively documented in the literature for their physical roles in the formation and sedimentation of flocs. They make irreplaceable contributions to the sewage treatment process, mainly reflected in two aspects. The first aspect is the sewage-purifying function. Filamentous bacteria are heterotrophic bacteria with a large specific surface area. They can fully absorb nutrients in sewage and degrade them, playing an essential role in sewage purification. The second aspect is the skeleton function. Filamentous bacteria are essential builders of biological flocs, serving as skeletons to support extracellular polymers during floc formation [3,4,5].

On the other hand, filamentous bacteria have a wide diversity and low environmental condition requirements, making them prone to overgrowth and posing significant challenges to the operation of sewage treatment plants [6,7,8,9].

In 1975, Eikelboom conducted pioneering and foundational work on classifying filamentous bacteria in activated sludge [10]. In the past few decades, many investigations have been undertaken on filamentous bacteria to better understand their quantity and determining factors, such as wastewater composition and the design and operation of treatment plants [11,12,13]. Based on traditional direct (or stained) microscopic observation and pure cultivation techniques, specific groups of filamentous bacteria were defined according to their preferred operating conditions and proposed control measures. However, this work requires experienced personnel and has relatively low sensitivity. In the mid-1990s, with the initial popularization of molecular methods, more and more research began to use fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) and HTS techniques to identify them. HTS, with its unprecedented sequencing depth, showed overwhelming advantages in analyzing complex bacterial communities, providing detailed information on bacterial community structure qualitatively and quantitatively [14,15]. If we suppose that all bacterial genomes in the sludge have the same copy number of 16S rRNA genes, in this case, the detection limit of 10,000 sample reads is about 0.01%, which is very helpful for analyzing sub-dominant groups with an abundance of 0.01–1%, suitable for filamentous bacteria.

The excessive proliferation of filamentous bacteria often results from a combination of multiple environmental factors, including the type and concentration of organic matter in the influent, the operation mode of the biochemical tank, sludge load, sludge age, DO, pH value, temperature, etc. Temperature is the most critical factor, especially in cold regions [16,17,18,19,20,21]. For example, wastewater treatment plants in Denmark and northern China experience periodic sludge expansion or foaming during winter and spring [22,23]. There are many kinds of filamentous bacteria, including those that can adapt to low-temperature environments, such as microfilamentous bacteria. A large number of research results showed that the dominant growth of microfilamentous bacteria is the main reason for sludge bulking caused by low temperature. The strain is a psychrophilic bacterium, and the optimum growth temperature range is 12–15 °C. The cold adaptation mechanism of psychrophilic bacteria includes the GC content of the genome, protein stability, transcription and translation regulation, cell membrane fluidity, osmotic pressure regulation, antioxidant loss and genome adaptive evolution, among others. However, the specific cold adaptation mechanism of microfilamentous bacteria has not been reported as of yet. In addition, due to the many influencing factors, the species and abundance of filamentous bacteria fluctuate. Although the above studies have identified essential members of filamentous bacterial communities, knowledge on the structure of filamentous bacterial communities in activated sludge is not comprehensive due to the lack of conclusions on the distribution characteristics of filamentous bacteria during special periods such as low temperature and variable temperature.

Hence, this study used HTS technology to conduct a detailed analysis of the filamentous community structure of activated sludge samples from a municipal sewage treatment plant in Changchun City, China, during variable-temperature and low-temperature periods. This study aimed to identify and quantify dominant filamentous bacteria through abundance fluctuation distribution and frequency distribution and to study the correlation between the existence and abundance of filamentous bacteria and the operating parameters and environmental factors of sewage treatment plants. Studying the composition, abundance distribution, main operating parameters, and environmental factors of filamentous bacterial communities not only has important guiding significance for the design and stable operation of sewage treatment systems but also enriches the theory of microbial ecology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wastewater Treatment Plant Description and Sampling

This paper researched activated sludge from the Chuanhu Municipal Sewage Treatment Plant in Changchun City to determine the distribution and changes of filamentous bacteria in activated sludge during variable-temperature and low-temperature periods. Changchun is located at 124°118’–127°02’ E longitude and 43°05’–45°15’ N latitude. It has a temperate continental monsoon climate with a large annual temperature range. Correspondingly, the sewage water temperature has a variable period, with a low-temperature period of up to five months. The total catchment area of the sewage treatment plant is 81.6 km2. Industrial wastewater accounts for about 50% of the influent quantity, and about 70% of chemical oxygen demand (COD) in sewage comes from industrial wastewater. The plant adopted an improved anaerobic–anoxic–oxic (A2O) process, and its effluent met the Class A standard of the “Pollutant Discharge Standards for Urban Sewage Treatment Plants” (GB18918-2002) [24]. The top view of Chuanhu Sewage Treatment Plant is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The top view of the Chuanhu Sewage Treatment Plant.

Sludge samples were collected during variable- and low-temperature periods (1 November 2023–12 March 2024) every five days. The collection sites were at the front (anaerobic), middle (anoxic) and end (aerobic) of the biochemical pool. For a comparison with the suitable temperature period, three samples were collected in September 2023, for a total of 30 samples. The water temperature in March was also below 12 °C, indicating a low-temperature period. However, due to the increase in residual sludge discharge from this month onwards, the month of stable operation at low temperatures was February. Therefore, samples were collected before the adjustment of sludge discharge in early March. The collected samples were evenly mixed and then centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 7 min, with a relative centrifugal force of 1888× g, and the concentrated sludge was stored in a −80 °C freezer for subsequent DNA extraction.

2.2. DNA Extraction and High-Throughput Sequencing

After centrifugation, the activated sludge sample was freeze-dried, and 0.5 g of freeze-dried sludge was used to extract DNA. DNA was purified using a custom plate-based extraction protocol based on the FastDNA® SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA). The FastDNA® SPIN Kit for Soil can successfully extract all types of environmental microorganisms from all types of soil, activated sludge and other samples, including Gram-negative bacteria, fungi, algae, actinomycetes, nematodes, etc. The total DNA purity is very high, which can be directly used in various downstream experiments such as qPCR, QCPR and high-throughput sequencing. Three groups were set up in parallel; 75 μL was extracted from each group. DNA quality was assessed by an ND- 2000 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA). The absorbance ratios at 260 and 280 nm and 260 and 230 nm were calculated. All DNA samples met the requirements of A260/A280 being around 1.8 and A260/A230 being larger than 1.7.

The bacterial 16S rRNA gene V3~V4 regions were amplified using universal primers 338F (5′–ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG–3′) and 806R (5′–GACTACHV GGGTWTCTAAT–3′) [25]. The reaction system measured 20 μL: 10 μL of Taq, 0.8 μL each of pre-primer and post-primer, 10 ng/μL DNA, and supplementation with nuclease-free pure water (ddH2O) to 20 μL. PCR reaction conditions: pre-denature at 95 °C for 3 min; 40 cycles, denaturation at 95 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 45 s; stable extension at 72 °C for 10 min. After detecting and purifying the amplified PCR products, a library was constructed and sequenced according to the operating procedures of the Illumina MiSeq platform (Majorbio, Shanghai, China). The sequences returned by HTS were quality-controlled, optimized, and clustered into OTUs with a similarity of 97% using Qiime (version 1.9.1) software. The filamentous bacteria in each sample were searched in the microbial database NCBI with a similarity of 97% and a minimum alignment length of 420 bps. The filamentous bacteria were annotated, and their abundance was calculated.

The calculation formula for filamentous bacteria abundance is as follows [26]:

where:

C = N/NT × 100%

- C—abundance of some filamentous bacteria annotated in NCBI database, %;

- N—the number of annotated filamentous bacteria sequences in NCBI database with 97% similarity;

- NT—total number of sequences.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Operation Status of the Sewage Treatment Plant

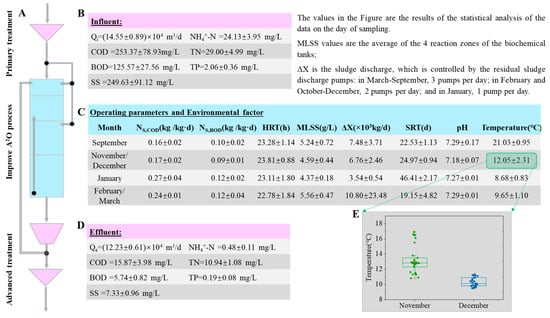

As shown in Figure 2, the main process of the Chuanhu Sewage Treatment Plant was an improved A2O process consisting of a pre-anoxic, anaerobic, anoxic, and aerobic tank. In order to avoid the influence of nitrogen nitrate in the returned sludge on the anaerobic phosphorus release reaction of phosphorus-accumulating bacteria, the first end of the A2O process was set as a pre-anoxic tank. A screen and a high-efficiency sedimentation tank were set before the main treatment process, and a high-efficiency clarification tank and a fibre cloth filter were set after it. The sewage entered the improved A2O biochemical tank in stages: pre-anoxic tank feed: 20 percent; anaerobic and anoxic tanks: 40 percent each. The wastewater treatment plant was completed in 2016 and has been in stable operation for eight years. While collecting sludge samples, the sewage plant staff provided the operating data for the day, the concentration of influent and effluent indicators, and critical environmental factors. The statistical analysis results are shown in Figure 2B–E. The sewage treatment plant had been operating at low load for a long time, with an actual hydraulic retention time (HRT) of about 23 h. The sludge concentration was maintained at around 5000 mg/L, and the pH value was stable at neutral. To mitigate the impact of temperature changes, suitable, variable-, and low-temperature periods were operated under different sludge age operating conditions. After the main process, high-efficiency clarification tanks and fibre filter cloth filters were set up as advanced treatment processes. Polyaluminum chloride and polyacrylamide were added to improve the removal efficiency of suspended solids (SS) and phosphorus. During the operation, all indexes of effluent concentration met the discharge standard. In January, with the lowest temperature, sludge bulking and foam on the surface of the biochemical tank occurred briefly, but it did not affect the pollutant removal efficiency of the sewage treatment plant, and all the indexes still met the discharge standards.

Figure 2.

The main process flow of the sewage treatment plant, operating parameters and environmental factors of the biochemical tank, and the concentration of the main indicators of inflow and outflow water. (A) Improved A2O process flow; (B) influent quality parameters; (C) biochemical tank main operating parameters and environmental factors; (D) effluent quality parameters; (E) box chart of temperature distribution for November and December. The data in the figure are average values ± standard deviation (n = 30, p = 0.683).

3.2. Filamentous Abundance Determined by HTS of 16s rRNA Gene

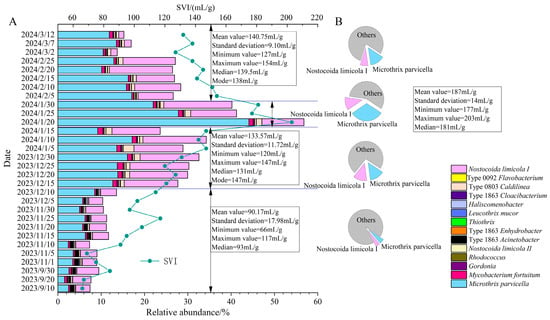

Figure 3 shows the total relative abundance of filamentous bacteria in 30 activated sludge samples. The total sequence of the 16s rRNA gene in the sample was 11,612, and the relative abundance of filamentous bacteria varied between 7.32% and 56.81%, with a distribution pattern consistent with the sludge volume index (SVI) value. Before 10 December 2023, the average SVI value was 90.17 mL/g, and the total abundance of filamentous bacteria fluctuated between 7.32% and 13.54%. From 15 December 2023 to 15 January 2024, the average SVI value increased to 133.57 mL/g, and the total abundance of filamentous bacteria increased, fluctuating between 23.62% and 34.26%. By late January 2024, the total abundance of filamentous bacteria reached its highest value of 56.81%, with an average SVI of 187.00 mL/g. Starting from February 2024, the total abundance of filamentous bacteria decreased to 13.72–23.38%, and the SVI value also decreased with an average of 141.75 mL/g.

Figure 3.

The variation pattern of SVI, the total abundance of filamentous bacteria and the cake plot of dominant filamentous bacteria in samples. (A) The variation pattern of SVI and the total abundance of filamentous bacteria (the abundance is the percentage of the 11,612 sequences that were hit under 97% similarity); (B) the percentage of Microthrix parvicella, Nostocoida limicola I, and other microorganisms.

3.3. Abundance Distribution of 14 Filamentous Bacteria

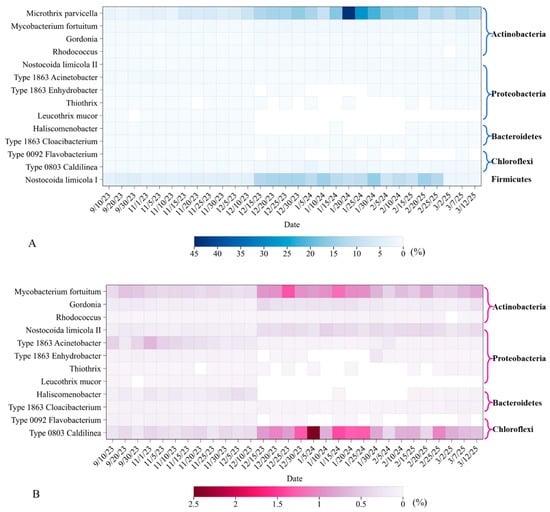

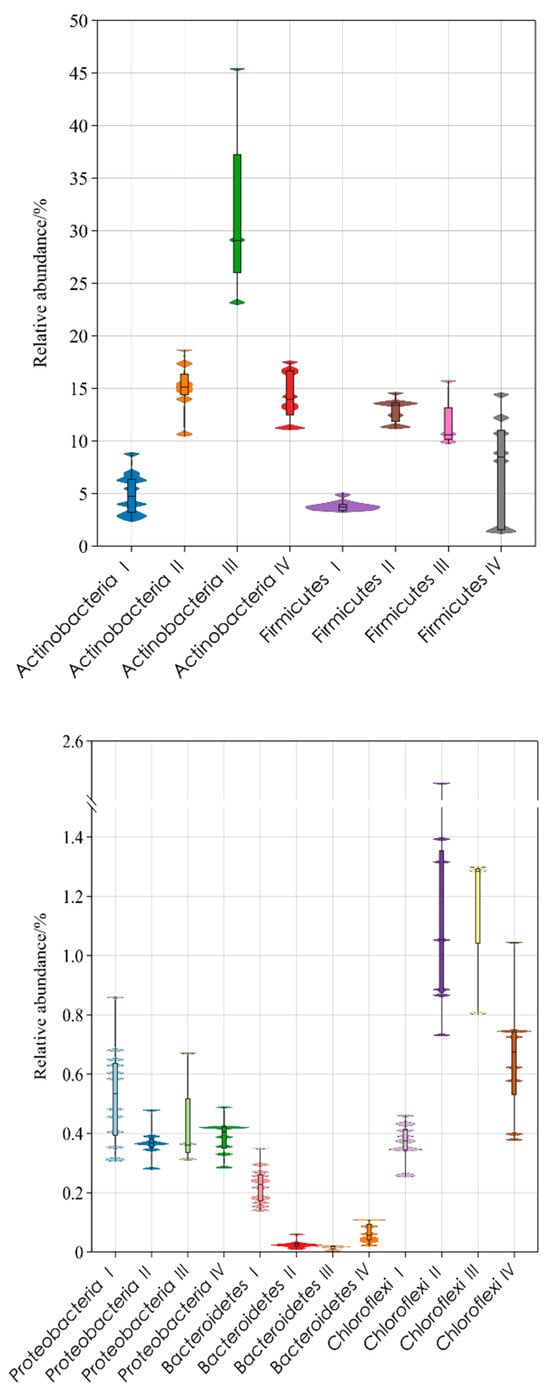

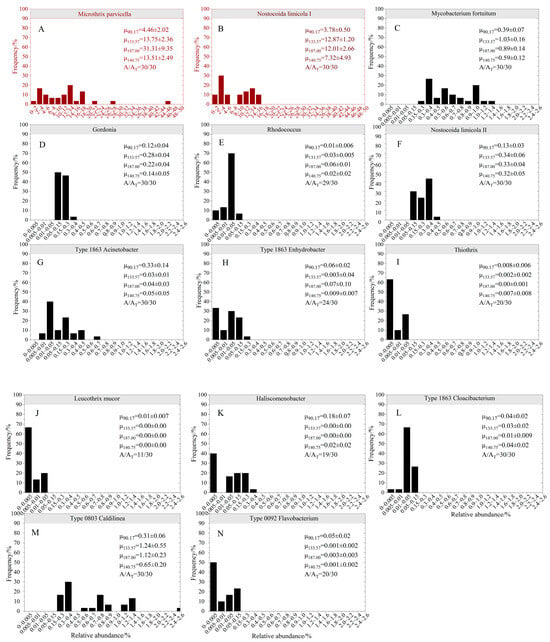

Figure 4 shows heatmaps of filamentous bacteria distribution with 97% similarity in activated sludge samples. From the samples, a total of 14 species of filamentous bacteria were detected, belonging to five phyla, including Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Chloroflexi, Firmicute, etc. The abundance distribution box diagram is shown in Figure 5. The abundance of Actinobacteria was the highest, and the changes were the most significant among all samples. Four species of bacteria belong to this species, including Microthrix parvicella, Mycobacterium fortuitum, Gordonia, and Rhodococcus. Among them, the most abundant filamentous bacterium was Microthrix parvicella, with a detection frequency of 100%. The frequency distribution histogram is shown in Figure 6. The abundance of Actinobacteria was dominated by Microthrix parvicella, which accounted for less than 10% of the total bacterial sequence in September, November, and early December. The abundance was higher than 10% from mid to late December to March of the second year, reaching a peak of 44.10% in January. Microthrix parvicella was the most abundant species in filamentous bacteria and had a significant and fluctuating proportion in the total bacterial sequence (Figure 3B). Mycobacterium fortuitum and Gordonia were detected in all samples with a frequency of 100%. Still, their abundance was low, accounting for an average of 0.64% and 0.16% of the total sequence numbers, respectively, with minor fluctuations. Rhodococcus was detected in 29 samples, but the highest abundance was only 0.02%.

Figure 4.

Overview heatmap of BFB community in 30 samples. Each row represents a filamentous bacterial group with a reference sequence, and each column represents an activated sludge sample. The white blocks are undetected groups. (A) Fourteen species of filamentous bacteria; (B) twelve species other than dominant filamentous bacteria.

Figure 5.

Changes in abundance of filamentous bacteria in samples. The abundance was the percentage of 11,612 sequences hit by bacterial species under 97% similarity. I: SVI mean value = 90.17 mL/g; II: SVI mean value = 133.57 mL/g; III: SVI mean value = 186.00 mL/g; IV: SVI mean value = 140.75 mL/g.

Figure 6.

Histogram of filamentous bacteria abundance distribution in Changchun nutrient removal wastewater treatment plant. μ90.17, μ133.57, μ187.00, and μ140.75 represent the average abundance of various filamentous bacteria when the SVI average values are 90.17, 133.57, 187.00, and 140.75 mL/g, respectively. The y-axis represents frequency distribution, and the x-axis represents the relative abundance of 16S rRNA of bacterial strains. AT is the total number of samples, and A is the number of samples with detected bacterial genera. (A) Microthrix parvicella; (B) Nostocoida limicola I; (C) Mycobacterium fortuitum; (D) Gordonia; (E) Rhodococcus; (F) Nostocoida limicola II; (G) Type 1863 Acinetobacter; (H) Type 1863 Enhydrobacter; (I) Thiothrix; (J) Leucothrix mucor; (K) Haliscomenobacterium; (L) Type 1863 Cloacibacterium; (M) Type 0803 Caldilinea; (N) Type 0092 Flavobacterium.

Firmicute species had a high abundance, with only Nostocoida limicola I belonging to this phylum out of 14 filamentous bacterial species. Nostocoida limicola I had a detection frequency of 100% and an abundance value lower than that of Microthrix parvicella, making it the second most dominant strain. The abundance change was divided into three stages: In September and early November December, the abundance was relatively low, with an average of 3.77%. It increased from mid-December until the end of February of the following year, reaching a peak of 15.74% and an average of 12.03%, but with relatively minor fluctuations. The abundance in the samples collected in March decreased, with an average of 1.42%.

The abundance of Chloroflexia was relatively low during the warm and cold periods, but after entering mid-December, the abundance increased and fluctuated significantly. Among the 14 filamentous bacteria, Type 0803 Caldilinea and Type 0092 Flavobacterium belonged to Chloroflexi. Type 0803 Caldilinea was present in all samples with a detection frequency of 100%, an average relative abundance of 0.71%, and the highest abundance of 2.46%. Among all detected filamentous bacteria, its abundance was only lower than that of Microthrix parvicella and Nostocoida limicola I. Type 0092 Flavobacterium had a low abundance and small fluctuations. It almost disappeared after entering December and was not detected or detected with extremely low abundance. It was speculated that it may have been eliminated due to its inability to adapt to low temperatures. The detection rate was 66.67%.

Figure 4 and Figure 5 show that the abundance of Proteobacteria was low, and the fluctuations were insignificant. Phylogenetically, Nostocoida limicola II, Type 1863 Acinetobacter, Type 1863 Enhydrobacter, Thiothrix, and Leucothrix mucor belong to the phylum Proteobacteria. Figure 4B and Figure 6 show that the detection rate of Nostocoida limicola II was 100%, but the abundance was relatively low, slightly higher during the low-temperature period than during the temperate period. Type 1863 Acinetobacter was detected in all samples, with the highest abundance of 0.65% in November. Three types of filamentous bacteria, including Type 1863 Enhydrobacter, Thiothrix, and Leucothrix mucor, were not detected in all samples and had low abundance. They almost disappeared during the low-temperature period, especially Thiothrix and Leucothrix mucor, whose abundance was less than 0.05%.

Type 1863 Cloacibacterium and Haliscomenobacterium belong to the phylum Bacteroidetes, with a detection rate of 100% for Type 1863 Cloacibacterium, but its abundance was relatively low, reaching up to 0.08% with no significant fluctuations. The highest abundance of Haliscomenobacter was 0.33%, with a detection rate of 63.33%. It was not detected during the low-temperature period from mid-December to mid-February of the following year.

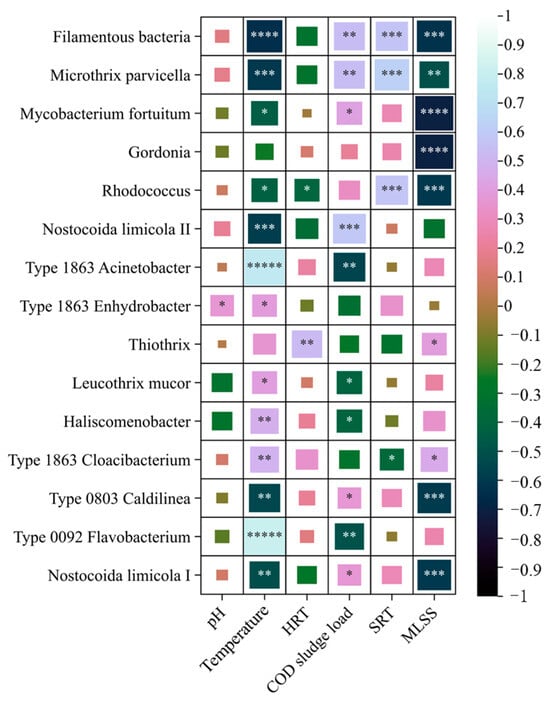

3.4. Correlation Analysis

According to research reports, there is no significant correlation between the composition and abundance distribution of filamentous bacterial communities in activated sludge and sewage and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), COD, total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), and ammonia nitrogen [22]. Therefore, this study used Pearson correlation analysis to reveal the correlation between microbial communities, biochemical tank operating parameters, and environmental factors (Figure 7). The total abundance of filamentous bacteria and water temperature (r = −0.65, p = 0.0001) were significantly correlated. There was also a correlation between SRT (r = 0.0001, p = 0.0010), COD sludge load (r = 0.54, p = 0.0021), and MLSS (r = −0.63, p = 0.0002). The biochemical tank of the Chuanhu Sewage Treatment Plant in Changchun City was equipped with an automatic detector for DO concentration and an automatic programmable logic controller (PLC) control system. The DO concentration in the tank was basically stable, and the value at the end of the aerobic pool was 2.0–0.5 mg/L; hence, DO was not an environmental factor for the fluctuation of filamentous bacteria abundance. Among the 14 filamentous bacteria, only Gordonia and Thiothrix showed no statistically significant correlation with water temperature. Microthrix parvicell, Rhodococcus, Nostocoida limicola I, Nostocoida limicola II, and Type 0803 Caldilina were significantly negatively correlated with water temperature. As the water temperature decreased, their abundance increased. Type 1863 Acinetobacter, Type 1863 Enhydrobacter, Haliscomenobacter, Leucothrix mucor, Type 1863 Cloacibacter, and Type 0092 Flavobacterium are significantly positively correlated with water temperature. When the water temperature decreased, their abundance decreased and they may even have been eliminated. Water temperature was the main influencing factor of fluctuations in filamentous bacterial abundance. There was a significant correlation between microfilament bacteria (r = 0.62, p = 0.0002) and Rhodococcus (r = 0.57, p = 0.0008) and sludge age. Microthrix parvicella and Nostocoida limicola II significantly positively correlated with sludge load. Three kinds of filamentous bacteria, especially Microthrix parvicella, existed in the environment where BOD load was lower than 0.2 kg BOD/(kg MLSS·d). Under this condition, with the increase in sludge load, the abundance increased. When the load was higher than 0.2 kg BOD/(kg MLSS·d), the growth and reproduction of the three strains were limited by competition, and their abundance was usually low. At the same time, Type 1863 Acinetobacter and Type 0092 Flavobacterium were significantly negatively correlated, with an absolute value of r greater than 0.5 and a p-value less than 0.05. Type 0803 Caldilinea and Type 0092 Flavobacterium, both of which belong to Chlorobacter, are common core filamentous bacteria that cause sludge bulking. According to the results of correlation analysis, the relative abundance distribution of the two species was mainly related to temperature and sludge load. There was a significant correlation between six types of bacteria—Microthrix parvicella, Mycobacterium fortuitum, Gordonia, Rhodococcus, Type 0803 Caldilina, and Nostocoida limicola I—and MLSS, with an absolute value of r greater than 0.5 and a p-value less than 0.05. There was no significant correlation between the abundance of filamentous bacteria and pH value or HRT.

Figure 7.

Correlation diagram between filamentous bacteria, operating parameters and environmental factors. * Indicates a significance level of p < 0.05; the more *, the smaller the p-value. The larger the square area in the figure, the greater the absolute value of the correlation coefficient.

3.5. Fluctuation Distribution of Total Abundance of Filamentous Bacteria

Previous studies have mainly focused on the community structure of activated sludge samples from different sewage treatment plants to identify bacterial communities in activated sludge by HTS. This study focused on fluctuating filamentous bacterial population abundance distribution during variable- and low-temperature periods. For comparison, 3 of the 30 sludge samples were collected in the thermophilic period, and the focus was on the dominant filamentous bacteria with high abundance and obvious fluctuations. Based on the HTS results, the filamentous bacterial community in the sewage treatment system was quantified. Filamentous bacteria accounted for an astonishing portion of the entire biomass, with significant fluctuations in total abundance. When the average SVI was 90.17 mL/g, the total filamentous bacteria abundance fluctuated between 7.32% and 13.54%, which was close to the total abundance of filamentous bacteria in normal activated sludge reported in the literature. It was reported that the filamentous bacteria abundance of fourteen municipal sewage treatment plants distributed in China, Hong Kong, Singapore, the United States, etc., was 2.71–15.65% [26]; this value reached 0.9–4.7% in the eight sewage treatment plants in the Taihu Lake basin of China [27], and 5.72% in a sewage treatment plant in a city in northern China [23]. When the average SVI value was 187.00 mL/g, the total abundance of filamentous bacteria was higher than that of filamentous bacteria in activated sludge during the excessive expansion period of nutrient removal wastewater treatment plants in northern China. A survey using FISH probe detection in five sewage treatment plants in Poland showed that filamentous bacteria accounted for 28 ± 3% of the total bacteria detected by the EUBmix probe, with the highest being close to 60%. The average number of filamentous bacteria in 28 nutrient removal systems in Denmark, which also used the FISH method, accounted for 24% of the total biomass, with the highest value being 46% [22,28].

The total abundance of filamentous bacteria was significantly correlated with sludge load, sludge age, water temperature, and sludge concentration. In addition to sludge concentration, other factors that affected the growth and reproduction of filamentous bacteria were the leading causes. Based on the results of 16S rRNA gene amplification and HTS, more than 90 searchable filamentous bacteria widely exist in sewage treatment plants belonging to 6 species and 42 genera [22,29,30]. Most of the 14 filamentous bacteria detected in this study can grow in environments with low organic load and are common filamentous bacteria in nutrient removal systems, but their growth rate was low. Therefore, the greater the sludge age, the more filamentous bacteria could accumulate in the biochemical tank [23,31,32,33]. Many research reports show that during the low-temperature operation of sewage plants in middle and high latitudes, the sludge easily expands, and the water surface is covered with foam. The total abundance of filamentous bacteria was significantly negatively correlated with the water temperature. The negative correlation between MLSS and the total abundance of filamentous bacteria was strong and significant (r = 0.63, p < 0.001). The total abundance of filamentous bacteria increased, and the SVI value increased. At this time, filamentous bacteria began to grow and reproduce, and mycelium extended outside the flocs. The floc structure of activated sludge became loose, and the concentration of returned sludge decreased, resulting in a decrease in MLSS concentration.

3.6. Structure of Filamentous Bacterial Community

In this study, a total of 14 species of filamentous bacteria were detected, with varying frequencies and abundance fluctuations. The complexity of different frequencies of filamentous bacteria revealed their universality and specificity. Microthrix parvicella, Nostocoida limicola I, Mycobacterium fortuitum, Type 0803 Caldilina, Nostocoida limicola II, Gordonia, Type 1863 Acinetobacter, and Type 1863 Cloacibacterium were detected in all samples with universality. Among them, Microthrix parvicella and Nostocoida limicola I showed significant fluctuations in abundance and strong specificity, while the specificity of the other six filamentous bacteria was not obvious. Although the detection frequency of Type 1863 Acinetobacter and Type 1863 Cloacibacterium was 100%, their role in wastewater treatment was limited due to their low abundance.

According to the detection results, the filamentous bacteria with high frequency and abundance and obvious fluctuations were microfilaments followed by Nostocoida limicola I, and the two were dominant. This was similar to three previous reports [23,26,27], and the filamentous bacteria Microthrix parvicella and Nostocoida limacola I were generally dominant in the normal activated sludge of sewage plants in Hong Kong, the Taihu Lake basin and other regions. At the same time, these two types of bacteria were also dominant filamentous bacteria in most sewage plants where sludge expansion occurs, among which Microthrix parvicella was almost the core filamentous bacteria in all seasonal and periodic bursts of expanded activated sludge [3,9,16,19,20]. The difference in abundance between expanded and non-expanded sludge samples indicated that Microthrix parvicella and Nostocoida limicola I were opportunistic expanding bacteria (similar to opportunistic pathogens) that adhere to flocs under certain conditions, resulting in high SVI values.

The other two bacteria in the phylum Actinobacteria, which had a detection rate of 100% but a lower abundance, were Mycobacterium fortuitum and Gordonia. Mycobacterium fortuitum is a widely present natural member of nutrient removal systems, with short hyphae that play a structural role and do not affect the sludge-settling performance of the system. Gordonia is a common foaming bacterium, which is highly correlated with the foam on the surface of the biochemical pool of the sewage treatment plant in winter. In this study, a small amount of foam also appeared in the sewage treatment plant in winter.

The abundance of Type 0803 Caldilina in the phylum Chloroflexia was second only to Microthrix parvicella and Nostocoida limicola I, but the fluctuations were relatively small. Artur Tomasz Mielczarek et al. used this probe to detect activated sludge from a Danish wastewater treatment plant and found that Type 0803 Caldilina was a core filamentous bacterium, accounting for 2.6–2.9% [22]. Similarly, A. Miłobędzka et al. tested activated sludge from Polish wastewater treatment plants and found that Type 0803 Caldilina accounted for an average of 2% of total bacteria, higher than the 0.71% observed in this study [28]. This may be related to detection technology. FISH technology has strong specificity and adopts a graded determination method for quantification, which first uses the universal probe CFXmix of Chloroflexi phylum for labeling and then uses more specific probes such as T0803–0654 for labeling and determination. The results were relatively high. However, for high-throughput technology to identify filamentous bacteria, although the standard hit length of at least 300 bp was controlled and the recognition rate was 97%, the length of the amplification area limited the recognition accuracy, and there may be situations where it cannot be detected, or the detected abundance is lower than the actual amount [34].

The abundance of Nostocoida limicola II in the phylum Proteobacteria was relatively low and fluctuated slightly, with the highest genus abundance approaching 0.5%. This differs from literature reports on Hong Kong sewage treatment plants, where Nostocoida limicola II was the most abundant expanding bacterium in normal activated sludge. Hong Kong has a warm climate with water temperatures ranging from 23 to 30 °C, while Changchun is in a temperate zone with an average winter water temperature of around 10 °C and a minimum of 8.6 °C. This may be the main reason for the differences [26,34].

3.7. Operating Parameters and Environmental Factors Driving Fluctuations in Filamentous Bacterial Abundance

The results of the Pearson correlation analysis indicated that the fluctuation distribution of filamentous bacteria abundance was greatly affected. The operating parameters with strong correlation were COD sludge load and SRT, while the environmental factor was water temperature. MLSS was the result of bacterial growth and reproduction and had a strong correlation with various filamentous bacteria.

In this study, the inflow of both domestic and industrial wastewater in the wastewater treatment plant accounted for 50%, and the main process was the improved A2O process. During operation, the COD sludge load was less than 0.30 kg COD/(kg MLSS·d), and the BOD sludge load was less than 0.15 kg BOD/(kg MLSS·d). The eight filamentous bacteria with a detection rate of 100% were common filamentous bacteria in nutrient removal systems. They had strong competitiveness at low organic substrate concentrations, especially Microthrix parvicella and Nostocoida limicola I, which were natural microbial community members in nutrient removal systems. They were common key bacteria with degradation functions and structural functions. When conditions changed, they were prone to overgrowth, which caused sludge bulking.

In situ observation, laboratory validation, and genome identification results indicated that Microthrix parvicella was a low-load strain that could maintain its growth with carbon sources such as acetate and glucose. More importantly, the cell surface was hydrophobic and contained lipolytic enzymes, which absorbed and utilized fatty substances (especially long-chain fatty acids). Unsaturated fatty acids can maintain cell membrane fluidity, thus enabling Microthrix parvicella to adapt to cold, so long-chain fatty acids are the main carbon source and energy source [35]. The nitrogen source is ammonia, and high free ammonia concentrations can also promote their growth [36]. Under this study’s low-sludge-load conditions, the relative abundance of Microthrix parvicella was positively correlated with sludge load. Still, there are literature reports that the absolute abundance of genes is negatively correlated with sludge load [37]. The difference may be because the decrease in MLSS concentration led to an increase in the calculated value of the sludge load. Therefore, it can be inferred that the absolute gene abundance inferred from research results may be more reliable. The detection frequency of Nostocoida limicola II in nutrient removal systems was also high, while the detection abundance in this study was low. The analysis showed a significant positive correlation between relative abundance and sludge load, which may be the same as Microthrix parvicella [38,39].

Changchun City centre is located at 43°45′ N latitude, with a large annual temperature range, and the sewage temperature varies between 6.7 and 22.9 °C. According to the research results, the water temperature was the main environmental factor affecting the total abundance of filamentous bacteria and the abundance of major filamentous bacteria, being significantly negatively correlated with the dominant strains Microthrix parvicella and Nostocoida limicola I. The optimum growth temperature of Microthrix parviella was 12–15 °C [39,40,41]. After entering the low-temperature period in December, the abundance increased significantly, leading to an increase in SVI. In the coldest month of January, the abundance reached the highest value, and sludge bulked, often accompanied by foam. The optimal growth temperature for Nostocoida limicola I was 15–37 °C, a wider range than other microorganisms, and it had a competitive advantage at low water temperatures, increasing relative abundance. Type 0803 Caldilina is commonly found in urban sewage treatment plants, with straight fibres mainly located inside the flocculent material but sometimes clustered, leading to sludge swelling. When Type 0803 proliferates and produces an open floc structure, its settling performance may deteriorate, especially in winter [22,28,42]. In this study, the abundance of Type 0803 Caldilina fluctuated and, overall, was higher in the low-temperature period than in the moderate- and variable-temperature periods. Other types of bacteria, such as Type 0092, were significantly positively correlated with temperature, and their abundance decreased during the variable-temperature period, while they were eliminated during the low-temperature period.

The temperature of sewage is also a key factor affecting the physiological functions of activated sludge microorganisms. Water temperature significantly impacts the metabolic activity of activated sludge microorganisms. During the low-temperature period, the growth and reproduction rate of most bacterial species decreased. To maintain the biomass in the biochemical tank, the sewage plant reduced the discharge of residual sludge. It operated two residual sludge pumps to increase the sludge age before the annual temperature change period, which started in October. As we entered the coldest month of January, the water temperature, growth and reproduction rate were at their lowest. Only one residual sludge pump was running, and the sludge age during the variable-temperature and low-temperature periods was more prolonged than during the suitable temperature period. Microautoradiography (MAR) analysis showed that Microthrix parvicella maintained activity in an extensive range of oxygen partial pressures. It grew well under aerobic and microaerophilic conditions but at a slower rate of 0.3~0.5 d–1. Sludge retention time also affected its growth and reproduction, and its abundance was positively correlated with sludge age [43,44]. Under anaerobic conditions, there was no growth, but it absorbed carbon sources [45]. The system operated for at least half of one sludge age, and microfilament bacteria could accumulate to a certain extent and then increase abundance and lead to an increase in SVI values, swell, or reach the critical value of swelling. This is why the abundance of microfilament bacteria only began to increase significantly in December and reached its peak in mid to late January.

According to the physiological and ecological research results of the main filamentous bacteria obtained through pure cultivation, the hyphae of Microthrix parvicella were about 200–400 μm long and hydrophobic on the surface, while the hyphae of Nostocoida limicola I and Type 0803 Caldilina were about 100–300 μm long and hydrophobic on the surface of Gordonia cells [10,46]. When the abundance of several filamentous bacteria was low, the mycelium served as the “skeleton” of activated sludge, playing a structural role. However, when the abundance was high, it loosened the floc structure, increased the SVI value, and ultimately affected the MLSS concentration in the biochemical tank. The detection frequency of Mycobacteria was 100%, but the abundance did not change significantly. The cell size was (0.2–0.8) μm × (1–10) μm, functioning aerobically, and grew slowly. Although this study found a significant strong correlation between the genus Mycobacterium and MLSS, it can be confirmed that this bacterium was the “skeleton” of activated sludge, playing a structural role and rarely causing sludge swelling and changes in sludge concentration [47].

4. Conclusions

This study used HTS technology to determine filamentous bacteria, and the results reflected the overall situation of filamentous bacterial communities in activated sludge from urban sewage treatment plants. Filamentous bacteria were very abundant during the suitable temperature period, variable-temperature period, and low-temperature period, accounting for 7.32–56.81% of the total bacteria in the activated sludge system. The distribution of filamentous bacteria abundance showed significant fluctuations, with the low-temperature period being higher than the suitable temperature period. A total of 14 filamentous bacteria were detected in the sludge samples, with different detection frequencies. Microthrix parvicella and Nostocoida limicola I had a detection frequency of 100% and significant fluctuations in abundance, making them the main contributors to the total abundance of filamentous bacteria. Low organic load is one of the main operating conditions for Microthrix parvicella and Nostocoida limicola I to have an advantage in competition. Microthrix parvicella is significantly negatively correlated with water temperature and significantly positively correlated with sludge age, revealing that low load, long sludge age, and low water temperature are the main operating parameters and environmental factors causing sludge expansion. This provides a theoretical basis for formulating specific strategies to control sludge expansion in northern China.

The research results provided detailed changes in filamentous bacterial communities during different suitable temperature periods, variable-temperature periods, and low-temperature periods. However, the understanding of the composition, structure, and abundance distribution fluctuations of filamentous bacterial communities is still limited, resulting in poor universality of various strategies and unsatisfactory sludge swelling inhibition effects. Further research should focus on the abundance distribution model of filamentous bacteria, the deterministic and stochastic driving mechanisms of microfilament composition, and other related topics. In addition, the low-temperature adaptation mechanism of mesophilic bacteria such as microfilamentous bacteria is the theoretical basis for putting forward the control strategy of sludge bulking at low temperature, and it is also the focus of future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, X.W.; methodology, L.N.; software, X.W.; validation, W.P.; formal analysis, W.P.; investigation, L.N.; resources, X.Z.; data curation, L.N.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; writing—review and editing, H.L.; visualization, W.P.; supervision, X.W.; project administration, X.W.; funding acquisition, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52170034).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xu Zhang was employed by the company Changchun Water Group Urban Drainage Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Aaron, M.S.; Mads, A.; Jes, V.; Per, H.N. The activated sludge ecosystem contains a core community of abundant organisms. ISME J. 2015, 10, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wen, D. Advances in spatial and temporal distribution and construction mechanisms of microbial communities in wastewater treatment systems. Environ. Eng. 2022, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sezgin, M.; Jenkins, D.; Parker, D. A Unified Theory of Filamentous Activated Sludge Bulking. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 1978, 50, 362–381. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, D.; Kaufman, W.; Jenkins, D. Physical Conditioning of Activated Sludge Floc. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 1971, 43, 1817–1833. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, D.; Kaufman, W.; Jenkins, D. Floc Breakup in Turbulent Flocculation Processes. J. Sanit. Eng. Div. 1972, 98, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Peng, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, X.; Yuan, Z. Filamentous and non–filamentous bulking of activated sludge encountered under nutrients limitation or deficiency conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 255, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.; He, Q.; Lin, G. Research on the Relationships between Filamentous Organisms and Flocculate Structure in Activated Sludge. China Water Wastewater 2000, 16, 5–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bakos, V.; Gyarmati, B.; Csizmadia, P.; Till, S.; Vachoud, L.; Nagy Göde, P.; Tardy, G.M.; Szilágyi, A.; Jobbágy, A.; Wisniewski, C. Viscous and filamentous bulking in activated sludge: Rheological and hydrodynamic modelling based on experimental data. Water Res. 2022, 214, 118–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zhang, N.; Han, H.; Ren, H.; Li, Y.; Hou, C.-Y.; Wang, C.-D.; Peng, Y.-Z. Microbial Diversity of Filamentous Sludge Bulking at Low Temperature. Environ. Sci. 2020, 41, 3373–3383. [Google Scholar]

- Eikelboom, D. Filamentous Organisms Observed in Activated Sludge. Water Res. 1975, 9, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, F.; Zhang, T. Advances in meta–omics research on activated sludge microbial Community. Microbiology 2019, 46, 2038–2052. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ju, F.; Zhang, T. Bacterial assembly and temporal dynamics in activated sludge of a full–scale municipal wastewater treatment plant. ISME J. 2015, 9, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Ning, D.; Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Shan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Brown, M.R.; Li, Z.; Van Nostrand, J.D.; et al. Author Correction: Global diversity and biogeography of bacterial communities in wastewater tre atment plants. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1183–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.; Kim, T.; Yu, G.; Jung, J. Bacterial community composition and diversity of a full–scale integrated fixed–film activated sludge system as investigated by pyrosequencing. J. Microbiol. Biotechn. 2010, 20, 1717–1723. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Zhang, T. Pathogenic bacteria in sewage treatment plants as revealed by 454 pyrosequencing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 7173–7179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Z. Sludge retention time affects the microbial community structure: A large–scale sampling of aeration tanks throughout China. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 261, 114140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, N.; Wang, R.; Qi, R.; Gao, Y.; Rossetti, S.; Tandoi, V.; Yang, M. Control strategy for filamentous sludge bulking: Bench–scale test and full–scale application. Chemosphere 2018, 210, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nierychlo, M.; Singleton, C.; Petriglieri, F.; Thomsen, L.; Petersen, J.F.; Peces, M.; Kondrotaite, Z.; Dueholm, M.S.; Nielsen, P.H. Low global diversity of Candidatus Microthrix, a troublesome filamentous organism in full–scale WWTPs. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 690251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Graaff, D.; Van Loosdrecht, M.; Pronk, M. Stable granulation of seawater–adapted aerobic granular sludge with filamentous Thiothrix bacteria. Water Res. 2020, 175, 115683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, N.; Qi, R.; Huang, B.; Jin, R.; Yang, M. Factors influencing Candidatus Microthrix parvicella growth and specific filamentous bulking control: A review. Chemosphere 2020, 244, 125371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhang, B.; Ning, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, T.; Wu, L.; Li, T.; Liu, W.; Zhou, J.; Wen, X. Seasonal dynamics of the microbial community in two full–scale wastewater treatment plants: Diversity, composition, phylogenetic group based assembly and co–occurrence pattern. Water Res. 2021, 200, 117295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielczarek, A.; Kragelund, C.; Eriksen, P.; Nielsen, P. Population dynamics of filamentous bacteria in Danish wastewater treatment plants with nutrient removal. Water Res. 2012, 46, 3781–3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yu, Z.; Qi, R.; Zhang, H. Detailed comparison of bacterial communities during seasonal sludge bulking in a municipal wastewater treatment plant. Water Res. 2016, 105, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB18918-2002; Discharge Standard of Pollutants for Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2002.

- Ma, Y.; Rui, D.; Dong, H.; Zhang, X.; Ye, L. Large-scale comparative analysis reveals different bacterial community structures in full- and lab-scale wastewater treatment bioreactors. Water Res. 2023, 242, 120222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhang, T. Profiling bulking and foaming bacteria in activated sludge by high throughput sequencing. Water Res. 2012, 46, 2772–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Peng, Z.; Zhi, L.; Li, H.; Zheng, K.; Li, J. Distribution and diversity of filamentous bacteria in wastewater treatment plants exhibiting foaming of Taihu Lake Basin, China. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miłobędzka, A.; Muszyn’ski, A. Population dynamics of filamentous bacteria identified in Polish full–scale wastewater treatment plants with nutrients removal. Water Sci. Technol. 2015, 71, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.; Kragelund, C.; Seviour, R.; Nielsen, J. Identity and ecophysiology of filamentous bacteria in activated sludge. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 969–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, A.; Horn, M.; Wagner, M. Probebase: An online resource for rRNA–targeted oligonucleotide probes. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2003, 31, 514–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Yan, G.; Fu, L.; Cui, B.; Wang, J.; Zhou, D. A review of filamentous sludge bulking controls from conventional methods to emerging quorum quenching strategies. Water Res. 2023, 236, 119922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krohn, H.; Khudur, L.; Biek, S.K.; Elliott, J.A.; Tabatabaei, S.; Jiang, C.; Wood, J.L.; Dias, D.A.; Dueholm, M.K.D.; Rees, C.A.; et al. Microbial population shifts during disturbance induced foaming in anaerobic digestion of primary and activated sludge. Water Res. 2025, 281, 123548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yao, J.; Wang, X. The microbial community in filamentous bulking sludge with the ultra–low sludge loading and long sludge retention time in oxidation ditch. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Guo, F.; Zhang, T. Population dynamics of bulking and foaming bacteria in a full–scale wastewater treatment plant over five years. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palm, J.C.; Jenkins, D.; Parker, D.S. Relationship Between organic loading, dissolved oxygen concentration and sludge settleability in the completely–mixed activated sludge process. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 1980, 52, 2482–2506. [Google Scholar]

- Kruit, J.; Hulsbeek, J.; Visser, A. Bulking sludge solved?! Water Sci. Technol. 2002, 46, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkel, T.; De León Gallegos, E.; Schönsee, C.; Hesse, T.; Jochmann, M.; Wingender, J.; Denecke, M. Evaluating the influence of wastewater composition on the growth of Microthrix parvicella by GCxGC/qMS and real–time PCR. Water Res. 2016, 88, 510–523. [Google Scholar]

- Seviour, E.; Eales, K.; Izzard, L.; Beer, M.; Carr, E.; Seviour, R. The in situ physiology of ‘Nostocoida limicola’ II, a filamentous bacterial morphotype in bulking activated sludge, using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and microautoradiography. Water Sci. Technol. 2006, 54, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackall, L.; Seviour, E.; Bradford, D.; Rossetti, S.; Tandoi, V.; Seviour, R. ‘Candidatus Nostocoida limicola’, a filamentous bacterium from activated sludge. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2000, 50, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sheik, A.; Muller, E.; Audinot, J.; Lebrun, L.; Grysan, P.; Guignard, C.; Wilmes, P. In situ phenotypic heterogeneity among single cells of the filamentous bacterium Candidatus Microthrix parvicella. ISME J. 2016, 10, 1274–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, S.; Tomei, M.; Nielsen, P. “Microthrix parvicella”, a filamentous bacterium causing bulking and foaming in activated sludge systems: A review of current knowledge. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kragelund, C.; Thomsen, T.; Mielczarek, A.; Nielsen, P. Eikelboom’s morphotype 0803 in activated sludge belongs to the genus Caldilinea in the phylum Chloroflexi. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2011, 76, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, S.; Marrengane, Z.; Bux, F. Application of quantitative RT–PCR to determine the distribution of Microthrix parvicella in full–scale activated sludge treatment systems. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 83, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noutsopoulos, C.; Mamais, D.; Andreadakis, A. Effect of solids retention time on Microthrix parvicella growth. Water SA 2007, 32, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.; Roslev, P.; Dueholm, T.; Nielsen, J. Microthrix parvicella, a specialized lipid consumer in anaerobic–aerobic activated sludge plants. Water Sci. Technol. 2002, 46, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.; Eales, K.; Seviour, R. Substrate uptake by Gordonia amarae in activated foams by FISH–MAR. Water Sci. Technol. 2006, 54, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Qi, R.; Tandoi, V.; Yang, M. Sludge bulking impact on relevant bacterial populations in a full–scale municipal wastewater treatment plant. Process Biochem. 2014, 49, 2258–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).