Heterotypic 3D Model of Breast Cancer Based on Tumor, Stromal and Endothelial Cells: Cytokines Interaction in the Tumor Microenvironment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

2.2. Spheroids Formation

2.3. Confocal Microscopy

2.4. Time-Lapse of Spheroid Formation Process

2.5. Live/Dead Staining

2.6. Reattachment Test

2.7. Investigation of the Potential of Cells in Spheroids for Invasion and Migration

2.8. Flow Cytometry

2.9. Western Blot

2.10. Immunocytochemistry

2.11. xMAP Analysis

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

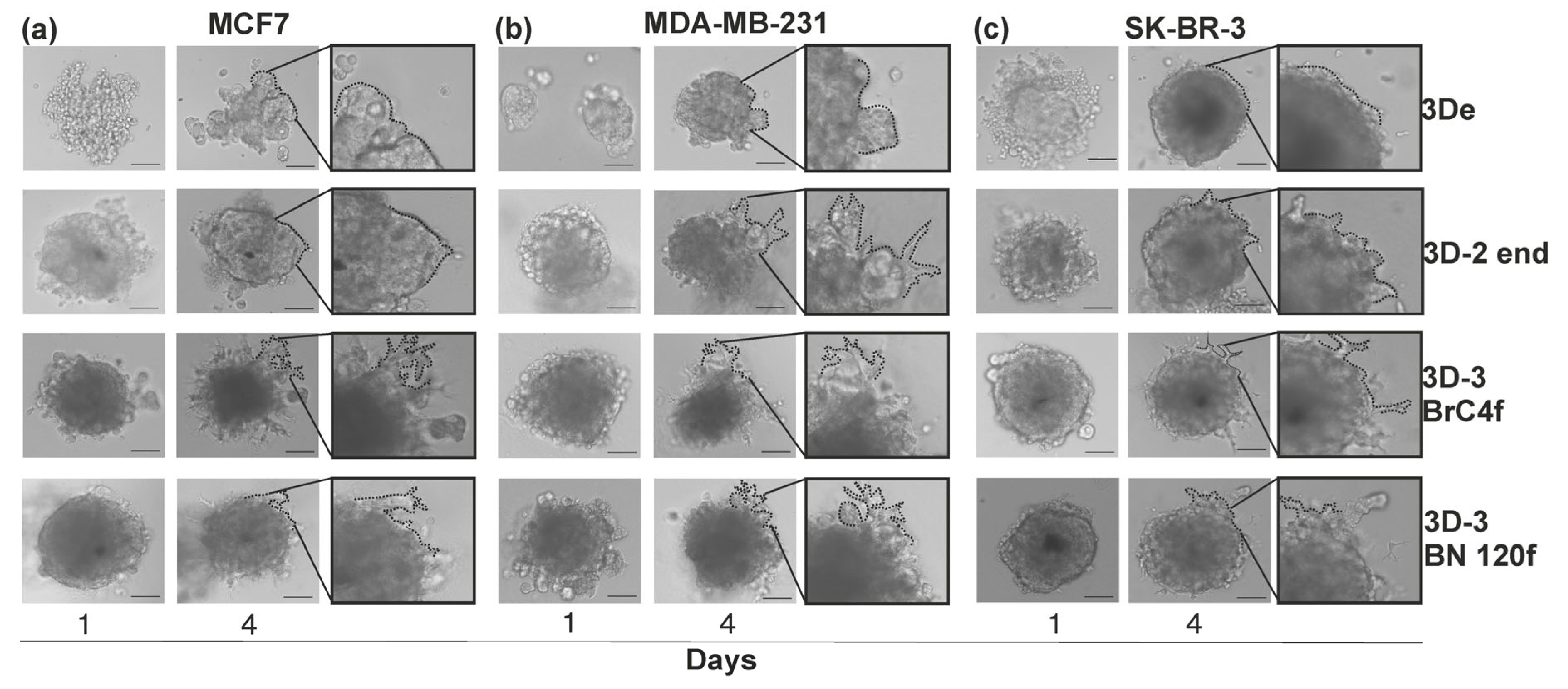

3.1. The Formation of a Heterotypic 3D Cell Model of Breast Cancer

3.2. Reattachment Test of Spheroid Models in Real-Time System

3.3. Migration/Invasion of Cancer Cells Regulated by Matrix Stiffness

3.4. Protein–Protein Interaction Network of Cytokines and Growth Factors via Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins of Database

3.5. The Analysis of the Secretory Profile of a Heterotypic Spheroid Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D-models | two dimensions cellular culture |

| 3D-models | three dimensions cellular culture |

| 3D-2-models | three dimensions cellular culture from tumor and endothelial cells |

| 3D-3-models | three dimensions cellular culture from tumor, endothelial and stromal cells |

| BC | breast cancer |

| BSA | bovine serum albumin |

| CAFs | cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| CSC | cancer stem cell |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| EGF | epidermal growth factor |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| FDA | fluorescein diacetate |

| FGF | fibroblast growth factor |

| RFP | red fluorescent protein |

| SDF1 | stromal cell-derived factor 1 |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| LIF | leukemia Inhibitory Factor |

| HGF | hepatocyte growth factor |

| PI | propidium iodide |

| SCGFβ | stem cell growth factor beta |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

References

- Tian, Y.; Yang, Y.; He, L.; Yu, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J. Exploring the Tumor Microenvironment of Breast Cancer to Develop a Prognostic Model and Predict Immunotherapy Responses. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; De Wever, O. The Plasticity of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Trends Cancer 2025, 11, 770–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, H.; Singh, L.; Lai, K.-S.; Parusheva-Borsitzky, T.; Ansari, S. Dynamics of Inflammatory Signals within the Tumor Microenvironment. World J. Exp. Med. 2025, 15, 102285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piwocka, O.; Sterzyńska, K.; Malińska, A.; Suchorska, W.M.; Kulcenty, K. Development of Tetraculture Spheroids as a Versatile 3D Model for Personalized Breast Cancer Research. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, A.; Gentile, M.T.; Pentimalli, F.; Cortellino, S.; Grieco, M.; Giordano, A. Multiple Aspects of Matrix Stiffness in Cancer Progression. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1406644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaukonen, R.; Mai, A.; Georgiadou, M.; Saari, M.; De Franceschi, N.; Betz, T.; Sihto, H.; Ventelä, S.; Elo, L.; Jokitalo, E.; et al. Normal Stroma Suppresses Cancer Cell Proliferation via Mechanosensitive Regulation of JMJD1a-Mediated Transcription. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishihara, S.; Haga, H. Matrix Stiffness Contributes to Cancer Progression by Regulating Transcription Factors. Cancers 2022, 14, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugovoi, M.E.; Karshieva, S.S.; Usatova, V.S.; Voznyuk, A.A.; Zakharova, V.A.; Levin, A.A.; Petrov, S.V.; Senatov, F.S.; Mironov, V.A.; Belousov, V.V.; et al. The Design of the Spheroids-Based in Vitro Tumor Model Determines Its Biomimetic Properties. Biomater. Adv. 2025, 169, 214178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, B.L.; Tollefsbol, T.O. Molecular, Cellular, and Technical Aspects of Breast Cancer Cell Lines as a Foundational Tool in Cancer Research. Life 2023, 13, 2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, S.; Oliveira, B.B.; Valente, R.; Ferreira, D.; Luz, A.; Baptista, P.V.; Fernandes, A.R. Breaking the Mold: 3D Cell Cultures Reshaping the Future of Cancer Research. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1507388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapałczyńska, M.; Kolenda, T.; Przybyła, W.; Zajączkowska, M.; Teresiak, A.; Filas, V.; Ibbs, M.; Bliźniak, R.; Łuczewski, Ł.; Lamperska, K. 2D and 3D Cell Cultures—A Comparison of Different Types of Cancer Cell Cultures. Arch Med Sci. 2018, 14, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdurakhmanova, M.M.; Leonteva, A.A.; Vasilieva, N.S.; Kuligina, E.V.; Nushtaeva, A.A. 3D Cell Culture Models: How to Obtain and Characterize the Main Models. Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2025, 29, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakhshiteh, F.; Bagheri, Z.; Soleimani, M.; Ahvaraki, A.; Pournemat, P.; Alavi, S.E.; Madjd, Z. Heterotypic Tumor Spheroids: A Platform for Nanomedicine Evaluation. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhans, S.A. Three-Dimensional in Vitro Cell Culture Models in Drug Discovery and Drug Repositioning. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagies, S.; Schlimpert, M.; Neumann, S.; Wäldin, A.; Kammerer, B.; Borner, C.; Peintner, L. Cells Grown in Three-Dimensional Spheroids Mirror in Vivo Metabolic Response of Epithelial Cells. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Sánchez, C.; González, B.; De Miguel-García, G.; Font-Cugat, A.; Marcote-Corral, I.; Alonso, S. Comparative Analysis of 3D-Culture Techniques for Multicellular Colorectal Tumour Spheroids and Development of a Novel SW48 3D-Model. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhwani, K.I.; Patel, Z.H.; Guenter, R.E.; Charania, A.A. A Hitchhiker’s Guide to Cancer Models. Trends Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1361–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Pacheco, S.; O’Driscoll, L. Pre-Clinical In Vitro Models Used in Cancer Research: Results of a Worldwide Survey. Cancers 2021, 13, 6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloomi, M.; Hamishehkar, H.; Jahanban Esfahlan, R. SpheroidSync as Edge Cutting Transfer Strategy for Uniform and Robust MCF7 Spheroids in 3D Culture. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 41237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardwell-Swanson, J.; Suzuki, M.; Dowell, K.G.; Bieri, M.; Thoma, E.C.; Agarkova, I.; Chiovaro, F.; Strebel, S.; Buschmann, N.; Greve, F.; et al. A Framework for Optimizing High-Content Imaging of 3D Models for Drug Discovery. SLAS Discov. Adv. Sci. Drug Discov. 2020, 25, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nushtaeva, A.A.; Savinkova, M.M.; Ermakov, M.S.; Varlamov, M.E.; Novak, D.D.; Richter, V.A.; Koval, O.A. Breast Cancer Cells in 3D Model Alters Their Sensitivity to Hormonal and Growth Factors. Cell Tissue Biol. 2022, 16, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonteva, A.; Abdurakhmanova, M.; Bogachek, M.; Belovezhets, T.; Yurina, A.; Troitskaya, O.; Kulemzin, S.; Richter, V.; Kuligina, E.; Nushtaeva, A. The Activity of Human NK Cells Towards 3D Heterotypic Cellular Tumor Model of Breast Cancer. Cells 2025, 14, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Hu, M.; Wang, J.; Gao, B.; Sha, X. Identification and Characterization of Cytokine Genes in Breast Cancer for Predicting Clinical Outcomes. Mediat. Inflamm. 2025, 2025, 8441796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurescu, S.; Buciu, V.; Șerban, D.; Borozan, F.; Tomescu, L.; Cobec, I.M.; Ilaș, D.G.; Sas, I. Role of Cytokines in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harel, K.; Czamanski-Cohen, J.; Cohen, M.; Lane, R.D.; Dines, M.; Caspi, O.; Weihs, K.L. Differences in Emotional Awareness Moderate Cytokine-Symptom Associations Among Breast Cancer Survivors. Brain Behav. Immun. 2025, 124, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyina, A.; Leonteva, A.; Berezutskaya, E.; Abdurakhmanova, M.; Ermakov, M.; Mishinov, S.; Kuligina, E.; Vladimirov, S.; Bogachek, M.; Richter, V.; et al. Exploring the Heterogeneity of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts via Development of Patient-Derived Cell Culture of Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nushtaeva, A.A.; Karpushina, A.A.; Ermakov, M.S.; Gulyaeva, L.F.; Gerasimov, A.V.; Sidorov, S.V.; Gayner, T.A.; Yunusova, A.Y.; Tkachenko, A.V.; Richter, V.A.; et al. Establishment of Primary Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines Using “Pulsed Hypoxia” Method and Development of Metastatic Tumor Model in Immunodeficient Mice. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nushtaeva, A.; Ermakov, M.; Abdurakhmanova, M.; Troitskaya, O.; Belovezhets, T.; Varlamov, M.; Gayner, T.; Richter, V.; Koval, O. “Pulsed Hypoxia” Gradually Reprograms Breast Cancer Fibroblasts into Pro-Tumorigenic Cells via Mesenchymal–Epithelial Transition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.C.; De Melo-Diogo, D.; Moreira, A.F.; Carvalho, M.P.; Correia, I.J. Spheroids Formation on Non-Adhesive Surfaces by Liquid Overlay Technique: Considerations and Practical Approaches. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13, 1700417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurakhmanova, M.M.; Ermakov, M.S.; Richter, V.A.; Koval, O.A.; Nushtaeva, A.A. The Optimization of Methods for the Establishment of Heterogeneous Three-Dimensional Cellular Models of Breast Cancer. Genes Cells 2022, 17, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Yi, T.; Li, H.; Tang, X.; Liu, D.; Wu, D.; Li, Y. Decoding Tumor Angiogenesis: Pathways, Mechanisms, and Future Directions in Anti-Cancer Strategies. Biomark. Res. 2025, 13, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.E.J.; Hinds, M.T. Extracellular Matrix Production and Regulation in Micropatterned Endothelial Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 427, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longstreth, J.H.; Wang, K. The Role of Fibronectin in Mediating Cell Migration. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2024, 326, C1212–C1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swoger, M.; Thanh, M.T.H.; Patteson, A.E. Vimentin—Force Regulator in Confined Environments. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2025, 94, 102521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, C.J.; Lemmon, C.A. Fibronectin: Molecular Structure, Fibrillar Structure and Mechanochemical Signaling. Cells 2021, 10, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesh, N.E.H.; Campeau, P.M.; Reinhardt, D.P. Fibronectin Isoforms in Skeletal Development and Associated Disorders. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2022, 323, C536–C549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiefner, A.; Gebauer, M.; Skerra, A. Extra-Domain B in Oncofetal Fibronectin Structurally Promotes Fibrillar Head-to-Tail Dimerization of Extracellular Matrix Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 17578–17588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labat-Robert, J. Cell–Matrix Interactions, the Role of Fibronectin and Integrins. A Survey. Pathol. Biol. 2012, 60, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-J.; Helfman, D.M. Up-Regulated Fibronectin in 3D Culture Facilitates Spreading of Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells on 2D through Integrin β-5 and Src. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, N.; Walzl, A.; Unger, C.; Rosner, M.; Krupitza, G.; Hengstschläger, M.; Dolznig, H. In Vitro Cell Migration and Invasion Assays. Mutat. Res./Rev. Mutat. Res. 2013, 752, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING Database in 2023: Protein–Protein Association Networks and Functional Enrichment Analyses for Any Sequenced Genome of Interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, V.K.; Mishra, B.; Mahapatra, S.; Swain, B.; Malhotra, D.; Saha, S.; Khanra, S.; Mishra, P.; Majhi, S.; Kumari, K.; et al. Molecular Insights on Signaling Cascades in Breast Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarychta, E.; Ruszkowska-Ciastek, B.; Bielawski, K.; Rhone, P. Stromal Cell-Derived Factor 1α (SDF-1α) in Invasive Breast Cancer: Associations with Vasculo-Angiogenic Factors and Prognostic Significance. Cancers 2021, 13, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sermaxhaj, F.; Dedić Plavetić, N.; Gozalan, U.; Kulić, A.; Radmilović Varga, L.; Popović, M.; Sović, S.; Mijatović, D.; Sermaxhaj, B.; Sopjani, M. The Role of Interleukin-7 Serum Level as Biological Marker in Breast Cancer: A Cross-sectional, Observational, and Analytical Study. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 20, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baram, T.; Oren, N.; Erlichman, N.; Meshel, T.; Ben-Baruch, A. Inflammation-Driven Regulation of PD-L1 and PD-L2, and Their Cross-Interactions with Protective Soluble TNFα Receptors in Human Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-Y.; Choi, J.-H.; Nam, J.-S. Targeting Cancer Stem Cells in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, W.; Yearsley, K.; Gao, J.X.; Shetuni, B.; Barsky, S.H. ERα Signaling through Slug Regulates E-Cadherin and EMT. Oncogene 2010, 29, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, T.; Ahn, R.; Yang, K.; Zhu, X.; Fu, Z.; Morin, G.; Bramley, R.; Cliffe, N.C.; Xue, Y.; Kuasne, H.; et al. CD44 Promotes PD-L1 Expression and Its Tumor-Intrinsic Function in Breast and Lung Cancers. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, T.; Yan, S.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, H.; Tu, C. Crosstalk of Pyroptosis and Cytokine in the Tumor Microenvironment: From Mechanisms to Clinical Implication. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, J.-H.; Chan, L.-C.; Li, C.-W.; Hsu, J.L.; Hung, M.-C. Mechanisms Controlling PD-L1 Expression in Cancer. Mol. Cell 2019, 76, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordanengo, L.; Proment, A.; Botta, V.; Picca, F.; Munir, H.M.W.; Tao, J.; Olivero, M.; Taulli, R.; Bersani, F.; Sangiolo, D.; et al. Shifting Shapes: The Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition as a Driver for Cancer Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coursier, D.; Calvo, F. CAFs vs. TECs: When Blood Feuds Fuel Cancer Progression, Dissemination and Therapeutic Resistance. Cell Oncol. 2024, 47, 1091–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilli, T.-M.; Meyer, J.; Morgan, J.R. Advances in the Formation, Use and Understanding of Multi-Cellular Spheroids. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2012, 12, 1347–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoosuf, N.; Navarro, J.F.; Salmén, F.; Ståhl, P.L.; Daub, C.O. Identification and Transfer of Spatial Transcriptomics Signatures for Cancer Diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Santos, M.J.; García-Martín, S.; Rubio-Fernández, M.; Gómez-López, G.; Al-Shahrour, F. Spatial Transcriptomics in Breast Cancer Reveals Tumour Microenvironment-Driven Drug Responses and Clonal Therapeutic Heterogeneity. NAR Cancer 2024, 6, zcae046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liao, Q.; Yuan, P.; Mei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Kang, X.; Zheng, S.; Yang, C.; et al. Spatially Resolved Atlas of Breast Cancer Uncovers Intercellular Machinery of Venular Niche Governing Lymphocyte Extravasation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchi-Mendes, T.; Lopes, N.; Brito, C. Heterotypic Tumor Spheroids in Agitation-Based Cultures: A Scaffold-Free Cell Model That Sustains Long-Term Survival of Endothelial Cells. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 649949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangogiannis, N.G. Fact and Fiction About Fibroblast to Endothelium Conversion: Semantics and Substance of Cellular Identity. Circulation 2020, 142, 1663–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Babaniyi, O.A.; Hall, T.J.; Barbone, P.E.; Oberai, A.A. Noninvasive In-Vivo Quantification of Mechanical Heterogeneity of Invasive Breast Carcinomas. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, A.; Zwierzina, M.; Koeck, S.; Gamerith, G.; Pechriggl, E.; Huber, J.M.; Lorenz, E.; Kelm, J.M.; Hilbe, W.; Zwierzina, H.; et al. Development of a 3D Angiogenesis Model to Study Tumour—Endothelial Cell Interactions and the Effects of Anti-Angiogenic Drugs. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, S.P.; Arya, N.; Kohler, E.; Xiang, S.; Christensen, J.; Shastri, V.P. Recapitulating Epithelial Tumor Microenvironment in Vitro Using Three Dimensional Tri-Culture of Human Epithelial, Endothelial, and Mesenchymal Cells. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Muenst, S.; Hoffman, J.; Starck, L.; Sarem, M.; Fischer, A.; Hutter, G.; Shastri, V.P. Mesenchymal-Endothelial Nexus in Breast Cancer Spheroids Induces Vasculogenesis and Local Invasion in a CAM Model. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascheid, D.; Baumann, M.; Pinnecker, J.; Friedrich, M.; Szi-Marton, D.; Medved, C.; Bundalo, M.; Ortmann, V.; Öztürk, A.; Nandigama, R.; et al. A Vascularized Breast Cancer Spheroid Platform for the Ranked Evaluation of Tumor Microenvironment-Targeted Drugs by Light Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Cai, Q.; Deng, L.; Ouyang, Q.; Zhang, X.H.-F.; Zheng, J. Invasion and Metastasis in Cancer: Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trelford, C.B.; Buensuceso, A.; Tomas, E.; Valdes, Y.R.; Hovey, O.; Li, S.S.-C.; Shepherd, T.G. LKB1 and STRADα Promote Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Spheroid Cell Invasion. Cancers 2024, 16, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buensuceso, A.; Borrelli, M.J.; Ramos Valdés, Y.; Shepherd, T.G. Reversible Downregulation of MYC in a Spheroid Model of Metastatic Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2025, 32, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammari, A.M.; Salman, M.I. Antimetastatic and Antitumor Activities of Oncolytic NDV AMHA1 in a 3D Culture Model of Breast Cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1331369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiou, G.; Radwanska, A.; Grapa, A.-I.; Beghelli-de La Forest Divonne, S.; Grall, D.; Schaub, S.; Hattab, M.; Pisano, S.; Poet, M.; Pisani, D.F.; et al. Fibronectin Extra Domains Tune Cellular Responses and Confer Topographically Distinct Features to Fibril Networks. J. Cell Sci. 2021, 134, jcs252957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, A.T.; Marquette, K.; Chang, C.-P.B.; Golas, J.; Jain, S.; Lam, M.-H.; Guffroy, M.; Leal, M.; Falahatpisheh, H.; Mathur, D.; et al. Anti-Extra Domain B Splice Variant of Fibronectin Antibody–Drug Conjugate Eliminates Tumors with Enhanced Efficacy When Combined with Checkpoint Blockade. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 1462–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonneau, C.; Eliès, A.; Kieffer, Y.; Bourachot, B.; Ladoire, S.; Pelon, F.; Hequet, D.; Guinebretière, J.-M.; Blanchet, C.; Vincent-Salomon, A.; et al. A Subset of Activated Fibroblasts Is Associated with Distant Relapse in Early Luminal Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteran, L.; Zait, Y.; Erez, N. It’s All about the Base: Stromal Cells Are Central Orchestrators of Metastasis. Trends Cancer 2024, 10, 208–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, B. Extracellular Matrix Stiffness: Mechanisms in Tumor Progression and Therapeutic Potential in Cancer. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.P.; Gaspar, V.M.; Mano, J.F. Design of Spherically Structured 3D in Vitro Tumor Models -Advances and Prospects. Acta Biomater. 2018, 75, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azamjah, N.; Soltan-Zadeh, Y.; Zayeri, F. Global Trend of Breast Cancer Mortality Rate: A 25-Year Study. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 2015–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siersbæk, R.; Kumar, S.; Carroll, J.S. Signaling Pathways and Steroid Receptors Modulating Estrogen Receptor α Function in Breast Cancer. Genes Dev. 2018, 32, 1141–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanos, T.; Rojo, L.J.; Echeverria, P.; Brisken, C. ER and PR Signaling Nodes during Mammary Gland Development. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz Bessone, M.I.; Gattas, M.J.; Laporte, T.; Tanaka, M.; Simian, M. The Tumor Microenvironment as a Regulator of Endocrine Resistance in Breast Cancer. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, T.; Laranjeira, P.; Caramelo, O.; Gil, A.M.; Paiva, A. Breast Cancer and Tumor Microenvironment: The Crucial Role of Immune Cells. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, D.; Jung, S.P.; Jeong, Y.; Bae, S.Y.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, S. Fibronectin Expression Is Upregulated by PI-3K/Akt Activation in Tamoxifen-Resistant Breast Cancer Cells. BMB Rep. 2017, 50, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Xu, L.; Zhang, J.; Ning, L.; Jiang, Y.; He, T.; Luo, J.; Chen, J.; Lv, Q.; Yang, X.; et al. Breast Cancer Cells Interact with Tumor-Derived Extracellular Matrix in a Molecular Subtype-Specific Manner. Biomater. Adv. 2023, 146, 213301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roswall, P.; Bocci, M.; Bartoschek, M.; Li, H.; Kristiansen, G.; Jansson, S.; Lehn, S.; Sjölund, J.; Reid, S.; Larsson, C.; et al. Microenvironmental Control of Breast Cancer Subtype Elicited through Paracrine Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-CC Signaling. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishtiah, A.A.; Yahaya, B.H. The Enrichment of Breast Cancer Stem Cells from MCF7 Breast Cancer Cell Line Using Spheroid Culture Technique. In Stem Cell Assays; Kannan, N., Beer, P., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 2429, pp. 475–484. ISBN 978-1-07-161978-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.; Ramasamy, K.; Pillai, S.M.A.; Santhamma, B.; Konda, S.; Pitta Venkata, P.; Blankenship, L.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Altwegg, K.A.; et al. LIF/LIFR Oncogenic Signaling Is a Novel Therapeutic Target in Endometrial Cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E.; Goldberg, A.F.; Lin, Z.; Ko, Y.-H.; Flomenberg, N.; Wang, C.; Pavlides, S.; Pestell, R.G.; Howell, A.; Sotgia, F.; et al. Anti-Estrogen Resistance in Breast Cancer Is Induced by the Tumor Microenvironment and Can Be Overcome by Inhibiting Mitochondrial Function in Epithelial Cancer Cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2011, 12, 924–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Woods, P.; Normolle, D.; Goff, J.P.; Benos, P.V.; Stehle, C.J.; Steinman, R.A. Downregulation of Estrogen Receptor and Modulation of Growth of Breast Cancer Cell Lines Mediated by Paracrine Stromal Cell Signals. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 161, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, L.V.; Bratton, M.R.; Zhu, Y.; Tilghman, S.L.; Muir, S.E.; Salvo, V.A.; Tate, C.R.; Elliott, S.; Nephew, K.P.; Collins-Burow, B.M.; et al. Effects of SDF-1–CXCR4 Signaling on microRNA Expression and Tumorigenesis in Estrogen Receptor-Alpha (ER-α)-Positive Breast Cancer Cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2011, 317, 2573–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, T.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Matsukawa, A. The Chemokine Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1/CCL2 Is a Promoter of Breast Cancer Metastasis. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 714–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira Almeida, C.; Correia-da-Silva, G.; Teixeira, N.; Amaral, C. Influence of Tumor Microenvironment on the Different Breast Cancer Subtypes and Applied Therapies. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 223, 116178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Liu, J.; Qian, H.; Zhuang, Q. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: From Basic Science to Anticancer Therapy. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Cintrón, K.M.; Gong, M.M.; Ayuso, J.M.; Tomko, L.A.; Beebe, D.J.; Virumbrales-Muñoz, M.; Ponik, S.M. Breast Fibroblasts and ECM Components Modulate Breast Cancer Cell Migration through the Secretion of MMPs in a 3D Microfluidic Co-Culture Model. Cancers 2020, 12, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunali, G.; Yanik, H.; Ozturk, S.C.; Demirkol-Canli, S.; Efthymiou, G.; Yilmaz, K.B.; Van Obberghen-Schilling, E.; Esendagli, G. A Positive Feedback Loop Driven by Fibronectin and IL-1β Sustains the Inflammatory Microenvironment in Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2023, 25, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, C.; Atzori, M.G.; Lacal, P.M.; Graziani, G. Role of VEGFs/VEGFR-1 Signaling and Its Inhibition in Modulating Tumor Invasion: Experimental Evidence in Different Metastatic Cancer Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Q.; Guo, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Feng, J. High Expression of SDF-1 and VEGF Is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Patients with Synovial Sarcomas. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 15, 2597–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisa, D.; Shabbir, A.; Mastri, M.; Taylor, T.; Aleksic, I.; McDaniel, M.; Suzuki, G.; Lee, T. Intramuscular VEGF Activates an SDF1-Dependent Progenitor Cell Cascade and an SDF1-Independent Muscle Paracrine Cascade for Cardiac Repair. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011, 301, H2422–H2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.S.; Hoadley, K.A.; Olsson, L.T.; Hamilton, A.M.; Bhattacharya, A.; Kirk, E.L.; Tipaldos, H.J.; Fleming, J.M.; Love, M.I.; Nichols, H.B.; et al. Hepatocyte Growth Factor Pathway Expression in Breast Cancer by Race and Subtype. Breast Cancer Res. 2021, 23, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, B.-B.; Cao, X.-S.; Wang, Y.-S.; Jiang, W.G.; Ye, L. Predictive Potential of Hepatocyte Growth Factor and Bone Morphogenetic Proteins in Lymphatic Metastasis of Breast Cancer. Transl. Breast Cancer Res. 2025, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuti, G.; Cappuzzo, F.; Duchnowska, R.; Jassem, J.; Fabi, A.; O’Brien, T.; Mendoza, A.D.; Landi, L.; Biernat, W.; Czartoryska-Arłukowicz, B.; et al. Increased MET and HGF Gene Copy Numbers Are Associated with Trastuzumab Failure in HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Su, X.; Li, Z.; Deng, L.; Liu, X.; Feng, X.; Peng, J. HGF/c-MET Pathway in Cancer: From Molecular Characterization to Clinical Evidence. Oncogene 2021, 40, 4625–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.C.; Silva, D.N.; Fortuna, V.; Silveira, B.M.; Orge, I.D.; De Santana, T.A.; Sampaio, G.L.; Paredes, B.D.; Ribeiro-dos-Santos, R.; Soares, M.B.P. Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF) Overexpression Increases the Angiogenic Potential of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerdes, I.; Wallerius, M.; Sifakis, E.; Wallmann, T.; Betts, S.; Bartish, M.; Tsesmetzis, N.; Tobin, N.; Coucoravas, C.; Bergh, J.; et al. STAT3 Activity Promotes Programmed-Death Ligand 1 Expression and Suppresses Immune Responses in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerdes, I.; Tsesmetzis, N.; Lovrot, J.; Rolny, C.; Bergh, J.C.S.; Rassidakis, G.; Foukakis, T. Regulation of PD-L1 in Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, e23088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, A.; Serna, N.; Mangues, R.; Villaverde, A.; Unzueta, U. Targeting the Chemokine Receptor CXCR4 for Cancer Therapies. Biomark. Res. 2025, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Kang, K.; Chen, P.; Zeng, Z.; Li, G.; Xiong, W.; Yi, M.; Xiang, B. Regulatory Mechanisms of PD-1/PD-L1 in Cancers. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittendorf, E.A.; Philips, A.V.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Qiao, N.; Wu, Y.; Harrington, S.; Su, X.; Wang, Y.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M.; Akcakanat, A.; et al. PD-L1 Expression in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.; Kieffer, Y.; Scholer-Dahirel, A.; Pelon, F.; Bourachot, B.; Cardon, M.; Sirven, P.; Magagna, I.; Fuhrmann, L.; Bernard, C.; et al. Fibroblast Heterogeneity and Immunosuppressive Environment in Human Breast Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 463–479.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; He, C.; Bi, Y.; Zhu, X.; Deng, D.; Ran, T.; Ji, X. Synergistic Effect of VEGF and SDF-1α in Endothelial Progenitor Cells and Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 914347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Lu, G.-L.; Huang, B.-X.; Wang, D.-W.; Shao, Y.; Lu, M.-J. Hypoxic Preconditioning Enhances Cellular Viability and Pro-Angiogenic Paracrine Activity: The Roles of VEGF-A and SDF-1a in Rat Adipose Stem Cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 580131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Y.; Qiao, L. Lung Epithelial-Endothelial-Mesenchymal Signaling Network with Hepatocyte Growth Factor as a Hub Is Involved in Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1462841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesch, M.; Onder, L.; Cheng, H.-W.; Novkovic, M.; Mörbe, U.; Sopper, S.; Gastl, G.; Jochum, W.; Ruhstaller, T.; Knauer, M.; et al. Interleukin 7-Expressing Fibroblasts Promote Breast Cancer Growth through Sustenance of Tumor Cell Stemness. OncoImmunology 2018, 7, e1414129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.-T.; Sun, W.; Zhang, J.-T.; Fan, Y.-Z. Cancer-associated Fibroblast Regulation of Tumor Neo-angiogenesis as a Therapeutic Target in Cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 3055–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhong, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Kridis, W.B.; Wang, R.; Shen, K.; Wang, Z.; Huang, R. Microenvironmental Regulation and Remodeling of Breast Cancer Angiogenesis: From Basic Mechanisms to Clinical Therapeutic Implications. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Fang, J.; Peng, J.; Wang, X.; Xing, P.; Jia, K.; Hu, J.; Wang, D.; Ding, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. PD-1/PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Breast Cancer: Research Insights and Sensitization Strategies. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Huseen, S.D.; Alabassi, H.M. Estimate the Relationship between CXCR4-SDF-1 Axis and Inhibitory Molecules (CTLA4 and PD-1) in Patients with Colon Cancer. Narra J. 2024, 4, e992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Qian, C.; Oupicky, D.; Sun, M. Targeting Pulmonary Tumor Microenvironment with CXCR4-Inhibiting Nanocomplex to Enhance Anti–PD-L1 Immunotherapy. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz9240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardizzone, A.; Bova, V.; Casili, G.; Repici, A.; Lanza, M.; Giuffrida, R.; Colarossi, C.; Mare, M.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Esposito, E.; et al. Role of Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor in Cancer: Biological Activity, Targeted Therapies, and Prognostic Value. Cells 2023, 12, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Ma, W.; Wu, J.; Wu, Q.; Sun, C. Paracrine Signaling in Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: Central Regulators of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mego, M.; Cholujova, D.; Minarik, G.; Sedlackova, T.; Gronesova, P.; Karaba, M.; Benca, J.; Cingelova, S.; Cierna, Z.; Manasova, D.; et al. CXCR4-SDF-1 Interaction Potentially Mediates Trafficking of Circulating Tumor Cells in Primary Breast Cancer. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Leonteva, A.; Kazakova, A.; Berezutskaya, E.; Ilyina, A.; Sergeevichev, D.; Vladimirov, S.; Bogachek, M.; Vakhrushev, I.; Makarevich, P.; Richter, V.; et al. Heterotypic 3D Model of Breast Cancer Based on Tumor, Stromal and Endothelial Cells: Cytokines Interaction in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cells 2026, 15, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020145

Leonteva A, Kazakova A, Berezutskaya E, Ilyina A, Sergeevichev D, Vladimirov S, Bogachek M, Vakhrushev I, Makarevich P, Richter V, et al. Heterotypic 3D Model of Breast Cancer Based on Tumor, Stromal and Endothelial Cells: Cytokines Interaction in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cells. 2026; 15(2):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020145

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeonteva, Anastasia, Alina Kazakova, Ekaterina Berezutskaya, Anna Ilyina, David Sergeevichev, Sergey Vladimirov, Maria Bogachek, Igor Vakhrushev, Pavel Makarevich, Vladimir Richter, and et al. 2026. "Heterotypic 3D Model of Breast Cancer Based on Tumor, Stromal and Endothelial Cells: Cytokines Interaction in the Tumor Microenvironment" Cells 15, no. 2: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020145

APA StyleLeonteva, A., Kazakova, A., Berezutskaya, E., Ilyina, A., Sergeevichev, D., Vladimirov, S., Bogachek, M., Vakhrushev, I., Makarevich, P., Richter, V., & Nushtaeva, A. (2026). Heterotypic 3D Model of Breast Cancer Based on Tumor, Stromal and Endothelial Cells: Cytokines Interaction in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cells, 15(2), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15020145