Reliable Gene Expression Normalization in Cucumber Leaves: Identifying Stable Reference Genes Under Drought Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Stress Treatments

2.2. RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

2.3. Optimization of PCR Conditions for Reference-Gene Assays

2.4. RT-qPCR Reaction Setup and Cycling Conditions

2.5. Data Analyses for Expression Stability

2.6. Validation with Drought-Responsive Target Genes

3. Results

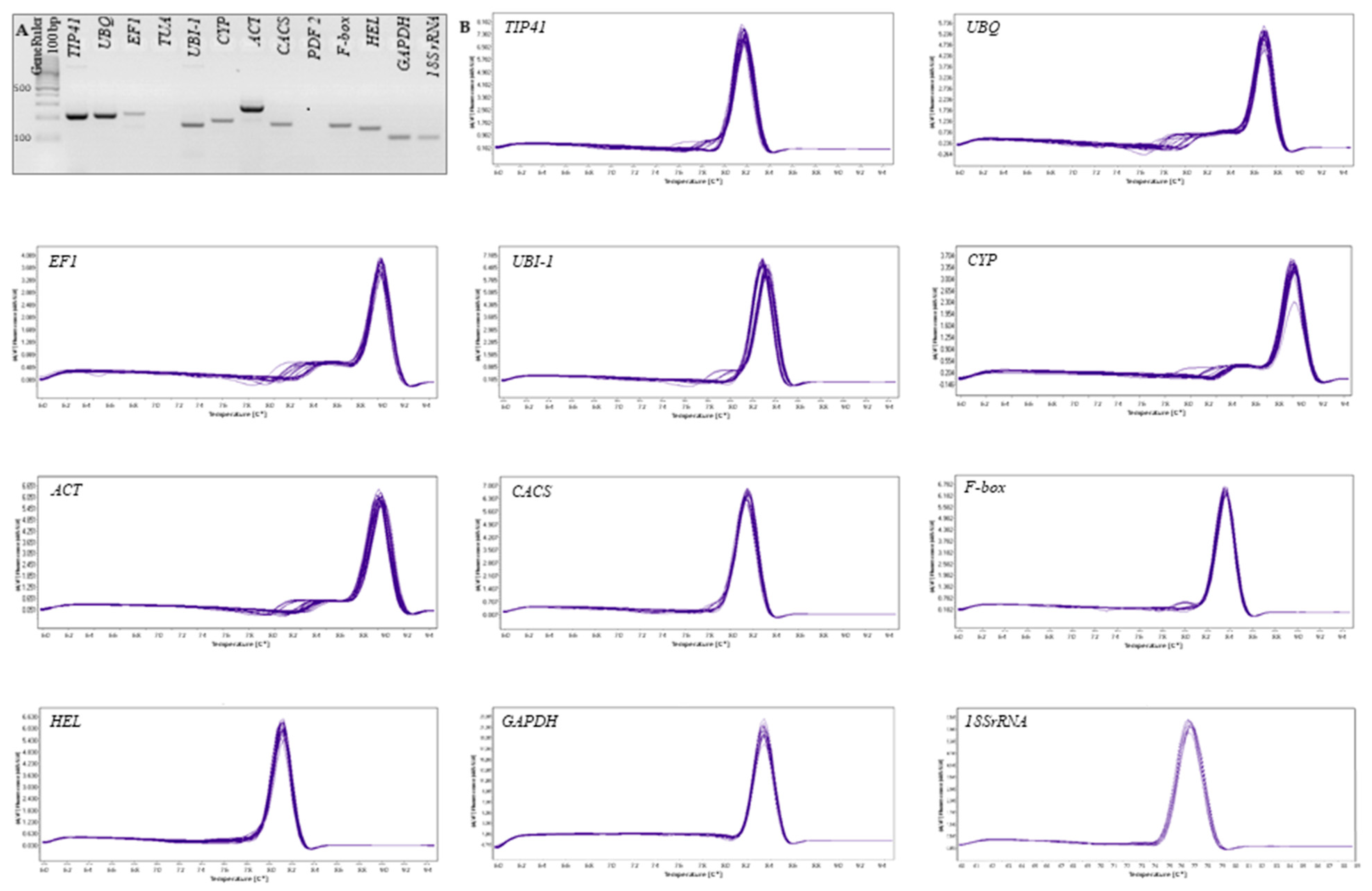

3.1. Primer Specificity and PCR Amplification Efficiency

3.2. Reference Gene Stability Rankings

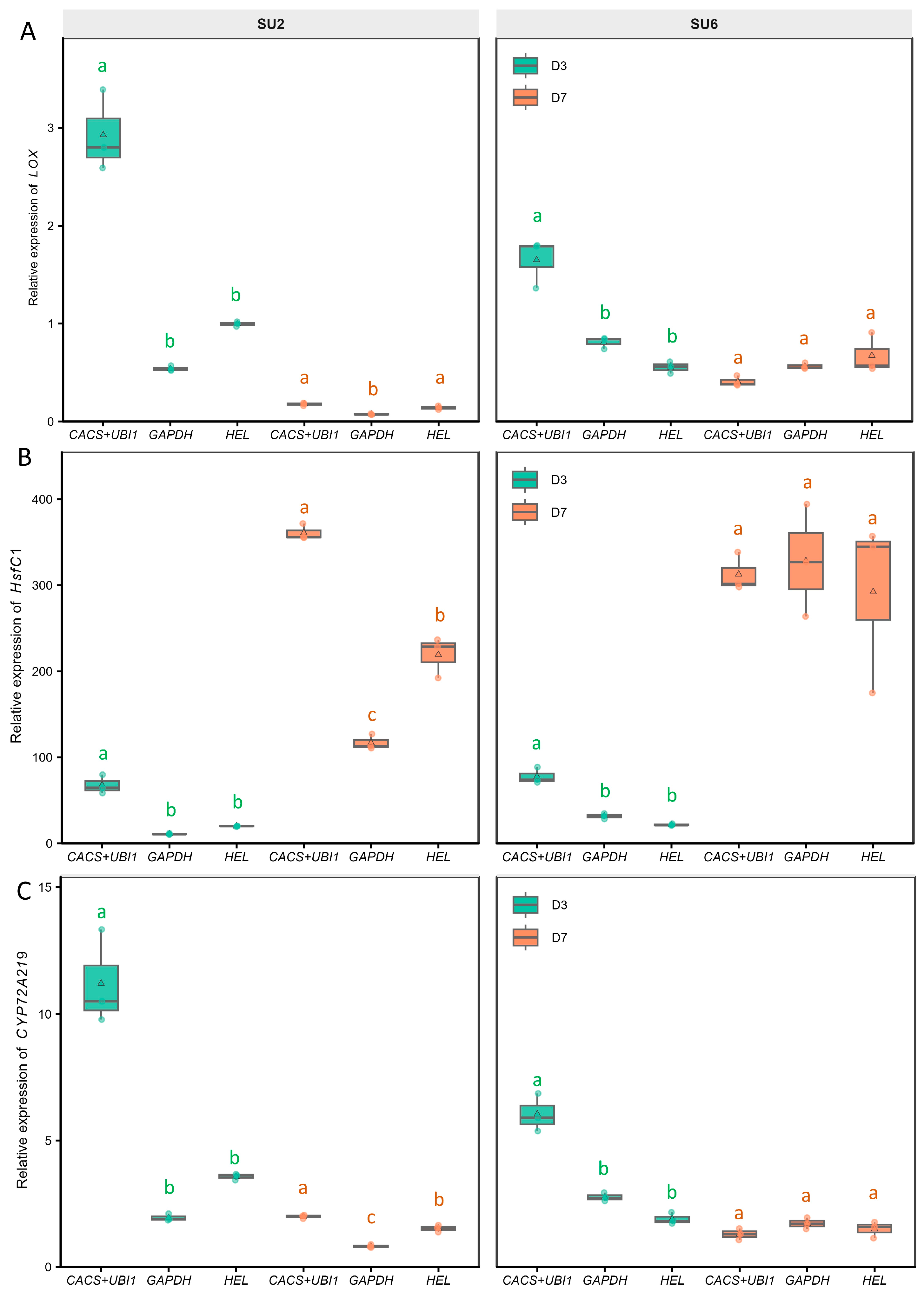

3.3. Validation of Reference Gene Selection on Target Gene Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABA | Abscisic Acid |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| BH | Benjamini–Hochberg |

| CCC | Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient |

| Ct | Cycle Threshold |

| DEG | Differentially Expressed Gene |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| HKG | Housekeeping Gene |

| MIQE | Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RIN | RNA Integrity Number |

| RNA-seq | RNA Sequencing |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR |

Appendix A

References

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; et al. The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Zhan, B.; Li, S. Selection and validation of reference genes for gene expression studies using quantitative real-time PCR in prunus necrotic ringspot virus-infected Cucumis sativus. Viruses 2022, 14, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, J.; Yang, S.; Chen, Y.; Tian, W.-M. Evaluation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR analysis of the gene expression in laticifers on the basis of latex flow in rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis muell. arg.). Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, M.; Azimi Moqadam, M.R.; Moradi, P.; Mohsenifard, E.; Shekari, F. Evaluation and validation of housekeeping genes in two contrast species of thyme plant to drought stress using real-time PCR. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 132, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tan, H.; Yu, J.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Diao, Y. Stable internal reference genes for normalizing real-time quantitative PCR in Baphicacanthus cusia under hormonal stimuli and UV irradiation, and in different plant organs. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souček, P.; Pavlů, J.; Medveďová, Z.; Reinöhl, V.; Brzobohatý, B. Stability of housekeeping gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings under differing macronutrient and hormonal conditions. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 26, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, research0034.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascia, T.; Santovito, E.; Gallitelli, D.; Cillo, F. Evaluation of reference genes for quantitative reverse--transcription polymerase chain reaction normalization in infected tomato plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2010, 11, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicot, N.; Hausman, J.-F.; Hoffmann, L.; Evers, D. Housekeeping gene selection for real-time RT-PCR normalization in potato during biotic and abiotic stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 2907–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.F.; Fonseca, C.; Ferreira, R.B.; Lourenço, A.M.; Monteiro, S. Reference gene validation for quantitative RT-PCR during biotic and abiotic stresses in Vitis vinifera. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Gao, Z.; Li, H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; Xu, W.; Song, S.; Ma, C.; Wang, S. Selection of reference genes for miRNA qRT-PCR under abiotic stress in grapevine. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.I.D.C.D.; Marini, N.; Santos, R.S.D.; Hoffman, B.S.F.; Alves-Ferreira, M.; De Oliveira, A.C. Selection and testing of reference genes for accurate RT-qPCR in rice seedlings under iron toxicity. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, P.; Shivhare, R.; Kaur, A.; Bansal, S.; Sonah, H.; Deshmukh, R.; Giri, J.; Lata, C.; Ram, H. Reference gene identification for gene expression analysis in rice under different metal stress. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 332, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, C.L.; Jensen, J.L.; Ørntoft, T.F. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: A model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5245–5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaffl, M.W.; Tichopad, A.; Prgomet, C.; Neuvians, T.P. Determination of stable housekeeping genes, differentially regulated target genes and sample integrity: BestKeeper—Excel-based tool using pair-wise correlations. Biotechnol. Lett. 2004, 26, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, N.; Best, S.; Jiang, J.; Thein, S.L. Selection of housekeeping genes for gene expression studies in human reticulocytes using real-time PCR. BMC Mol. Biol. 2006, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B. RefFinder: A web-based tool for comprehensively analyzing and identifying reference genes. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2023, 23, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klie, M.; Debener, T. Identification of superior reference genes for data normalization of expression studies via quantitative PCR in hybrid roses (Rosa hybrida). BMC Res. Notes 2011, 4, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, W.; Han, S.; Yang, W.; Qi, L. Reference gene selection for quantitative real-time PCR normalization in Caragana intermedia under different abiotic stress conditions. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løvdal, T.; Lillo, C. Reference Gene Selection for quantitative real-time PCR normalization in tomato subjected to nitrogen, cold, and light stress. Anal. Biochem. 2009, 387, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Nijhawan, A.; Tyagi, A.K.; Khurana, J.P. Validation of housekeeping genes as internal control for studying gene expression in rice by quantitative real-time PCR. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 345, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czechowski, T.; Stitt, M.; Altmann, T.; Udvardi, M.K.; Scheible, W.-R. Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Li, R.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Gu, X.; Fan, W.; Lucas, W.J.; Wang, X.; Xie, B.; Ni, P.; et al. The genome of the cucumber, Cucumis sativus L. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 1275–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Cao, Y.; Qi, C.; Li, S.; Liu, L.; Wang, G.; Mao, A.; Ren, S.; Guo, Y.-D. CsATAF1 positively regulates drought stress tolerance by an ABA-dependent pathway and by promoting ROS scavenging in cucumber. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 930–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Du, Q.; Bai, L.; Sun, M.; Li, Y.; He, C.; Wang, J.; Yu, X.; Yan, Y. Interference of CsGPA1, the α-submit of g protein, reduces drought tolerance in cucumber seedlings. Hortic. Plant J. 2021, 7, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Kumari, K.; Munshi, A.D.; Raju, D.; Talukdar, A.; Singh, D.; Hongal, D.; Iquebal, M.A.; Bhatia, R.; Bhattacharya, R.C.; et al. Physio-chemical and molecular modulation reveals underlying drought resilience mechanisms in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Sci. Hortic. 2024, 328, 112855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Jiang, B.; Peng, Q.; Liu, W.; He, X.; Liang, Z.; Lin, Y. Transcriptome analyses in different cucumber cultivars provide novel insights into drought stress responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migocka, M.; Papierniak, A. Identification of suitable reference genes for studying gene expression in cucumber plants subjected to abiotic stress and growth regulators. Mol. Breed. 2011, 28, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Qin, X.; Gao, L.; Li, Q.; Li, S.; He, C.; Li, Y.; Yu, X. Selection of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR analysis in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.), pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch.) and cucumber–pumpkin grafted plants. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Ma, S.; Liang, M.; Wang, X.; Gao, L.; Tian, Y. Reference genes identification for qRT-PCR normalization of gene expression analysis in Cucumis sativus under Meloidogyne incognita infection and Pseudomonas treatment. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1061921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kłosińska, U.; Nowakowska, M.; Szczechura, W.; Nowak, K.; Treder, W.; Klamkowski, K.; Wójcik, K. Opracowanie genetycznych, fizjologicznych i biochemicznych podstaw tolerancji ogórka na stres niedoboru wody. Biulletin Plant Breed. Acclim. Inst. 2019, 286, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Yang, T. RNA Isolation from highly viscous samples rich in polyphenols and polysaccharides. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 2002, 20, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Hao, J.; Meng, Y.; Luo, L.; Li, J. Identifying optimal reference genes for the normalization of microRNA expression in cucumber under viral stress. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warzybok, A.; Migocka, M. Reliable reference genes for normalization of gene expression in cucumber grown under different nitrogen nutrition. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Wu, S.; Sun, H.; Wang, X.; Tang, X.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, S.; Xu, Y.; Weng, Y.; et al. CuGenDBv2: An updated database for cucurbit genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D1457–D1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S. ctrlGene: Assess the Stability of Candidate Housekeeping Genes, R Package Version 4.3.3. 2019. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ctrlGene (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R foundation for statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.; Coulouris, G.; Zaretskaya, I.; Cutcutache, I.; Rozen, S.; Madden, T.L. Primer-BLAST: A tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- de Mendiburu Delgado, F.; Reinhard, S. Agricolae—A Free Statistical Library for Agricultural Research 2007, R package Version 4.3.3. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=agricolae (accessed on 1 October 2019).

- Diedenhofen, B.; Musch, J. Cocor: A comprehensive solution for the statistical comparison of correlations. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Martín, L.; Hernández, M.; Yeramian, N.; Pérez, D.; Eiros, J.M.; Valero, A.; Rodríguez-Lázaro, D. The impact of the variability of RT-qPCR standard curves on reliable viral detection in wastewater surveillance. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guenin, S.; Mauriat, M.; Pelloux, J.; Van Wuytswinkel, O.; Bellini, C.; Gutierrez, L. Normalization of qRT-PCR data: The necessity of adopting a systematic, experimental conditions-specific, validation of references. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.-H.; Xu, X.-W.; Lin, X.-J.; Zhang, W.-J.; Chen, X.-H. Identification of differentially expressed genes in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) root under waterlogging stress by digital gene expression profile. Genomics 2012, 99, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Hu, J.; Li, J. Identification and validation of suitable internal reference genes for SYBR-GREEN qRT-PCR studies during cucumber development. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2014, 89, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Ren, J.; Bai, F.; Hao, L. Selection and validation of reference genes for gene expression studies in Pseudomonas brassicacearum GS20 using real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.T.; Poolakkalody, N.J.; Shah, J.M. Plant reference genes for development and stress response studies. J. Biosci. 2018, 43, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, H.; Zhao, Z.; Qian, C.; Sui, Y.; Malik, A.A.; Chen, J. Selection of appropriate reference genes for gene expression studies by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction in cucumber. Anal. Biochem. 2010, 399, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expósito-Rodríguez, M.; Borges, A.A.; Borges-Pérez, A.; Pérez, J.A. Selection of internal control genes for quantitative real-time RT-PCR studies during tomato development process. BMC Plant Biol. 2008, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotrade, P.; Sehr, E.M.; Wischnitzki, E.; Brüggemann, W. Comparative transcriptomics-based selection of suitable reference genes for normalization of RT-qPCR experiments in drought-stressed leaves of three european quercus species. Tree Genet. Genomes 2019, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinati, Z.; Nazari, L. Deciphering the molecular basis of abiotic stress response in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) using RNA-seq meta-analysis, systems biology, and machine learning approaches. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi Mashaki, K.; Garg, V.; Nasrollahnezhad Ghomi, A.A.; Kudapa, H.; Chitikineni, A.; Zaynali Nezhad, K.; Yamchi, A.; Soltanloo, H.; Varshney, R.K.; Thudi, M. RNA-seq analysis revealed genes associated with drought stress response in kabuli chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Lozano, I.; Arnedo, M.S.; Grimplet, J.; Díaz, A. Selection of novel reference genes by RNA-seq and their evaluation for normalising Real-Time qPCR expression data of anthocyanin-related genes in lettuce and wild relatives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ksouri, N.; Jiménez, S.; Wells, C.E.; Contreras-Moreira, B.; Gogorcena, Y. Transcriptional responses in root and leaf of Prunus persica under drought stress using RNA sequencing. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhang, N.; Si, H.; Calderón-Urrea, A. Selection and validation of reference genes for RT-qPCR analysis in potato under abiotic stress. Plant Methods 2017, 13, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. Bioinform. Action 2011, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. 2015. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 24 June 2015).

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, S.; Pyl, P.T.; Huber, W. HTSeq—A python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Annotation | Gene ID in Cucumber | Primer Sequence | Amplicon Size (bp) | E (%) | R2 | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT | Actin | CsGy6G026130 | F:ATGACGCAGATAATGTTTGAG | 290 | 94.8 | 0.999 | [33] |

| R:GGAGAATGGCATGAGGGAGGG | |||||||

| CACS | AP-2 complex subunit mu-1 | CsGy3G044260 | F:TGGGAAGATTCTTATGAAGTGC | 160 | 102.3 | 0.999 | [28] |

| R:CTCGTCAAATTTACACATTGGT | |||||||

| CYP | Cyclophilin | CsGy7G014440 | F:GCTGGACCTGGAACCAACGGA | 190 | 98.4 | 0.999 | [34] |

| R:TCTAAGAGAGCTGGCCACAAT | |||||||

| EF1α | Elongation factor 1-α | CsGy2G009450 | F:ACTGGTGGTTTTGAGGCTGGT | 205 | 104.2 | 0.999 | [33] |

| R:CTTGGAGTATTTGGGTGTGGT | |||||||

| F-box | F-box protein | CsGy5G004880 | F:GGTTCATCTGGTGGTCTT | 160 | 103.1 | 0.993 | [34] |

| R:CTTTAAACGAACGGTCAGTCC | |||||||

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | CsGy3G019880 | F:GCCTTGGTCCTCCCTTCTCTT | 133 | 107.0 | 0.999 | [33] |

| R:ATGCAGCATTCACCTCTTCAG | |||||||

| HEL | RNA helicase | CsGy5G005520 | F:TTCTCGAAGATTTAGTGATTCATGTG | 160 | 107.3 | 0.999 | [28] |

| R:CAATGGACGAATGCAAAGG | |||||||

| TIP41-like | TIP41-like family protein | CsGy7G006670 | F:CAACAGGTGATATTGGATTATGATTATAC | 200 | 100.8 | 0.999 | [34] |

| R:GCCAGCTCATCCTCATATAAG | |||||||

| UBI-1 | Ubiquitin-like protein | CsGy2G005440 | F:CTAATGGGGAGTGGGGAAGTA | 160 | 100.1 | 0.999 | [33] |

| R:GTCTGGATGGACAATGTTGAT | |||||||

| UBQ | Polyubiquitin | CsGy6G011285 | F:CACCAAGCCCAGAAGATC | 200 | 101.9 | 0.999 | [30] |

| R:TAAACCTAATCACCACCAGC | |||||||

| 18S rRNA | Ribosomal RNA-processing protein 17 | CsGy4G017630 | F:CAAAGCAAGCCTACGCTCTGT | 127 | 153.2 | 0.955 | [33] |

| R:CTATGAAATACGAATGCCCCC | |||||||

| PDF2 | Sucrose-phosphatase | CsGy5G025470 | F:GTAGGACCTGAACCAACTA | - | - | - | [30] |

| R:CTTCACGCAGGGAAGA | |||||||

| TUA | α-Tubulin | CsGy4G011690 | F:CAAGGAAGATGCTGCCAATAA | - | - | - | [33] |

| R:CCAAAAGGAGGGAGCCGGAC |

| Reference Gene | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-BOX | UBI-1 | HEL | TIP41-like | CACS | EF1α | UBQ | CYP | ACT | GAPDH | |

| Ranking | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| n | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Geo Mean (Ct) | 23.94 | 24.31 | 23.18 | 23.09 | 22.27 | 17.19 | 19.21 | 18.47 | 20.53 | 18.70 |

| AR (Ct) | 23.95 | 24.31 | 23.18 | 23.09 | 22.28 | 17.20 | 19.22 | 18.48 | 20.55 | 18.73 |

| Min. (Ct) | 23.13 | 23.19 | 22.36 | 22.17 | 21.07 | 16.29 | 18.31 | 17.06 | 19.74 | 17.54 |

| Max. (Ct) | 24.85 | 25.19 | 24.52 | 24.20 | 23.65 | 18.04 | 20.49 | 19.67 | 22.26 | 20.59 |

| SD (± Ct) | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.63 | 0.78 |

| CV (%Ct) | 1.70 | 1.75 | 2.10 | 2.21 | 2.37 | 2.68 | 2.90 | 2.93 | 3.05 | 4.17 |

| Min. (x-fold) | −1.76 | −2.17 | −1.76 | −1.89 | −2.30 | −1.86 | −1.87 | −2.66 | −1.73 | −2.24 |

| Max. (x-fold) | 1.87 | 1.84 | 2.54 | 2.16 | 2.61 | 1.81 | 2.42 | 2.29 | 3.31 | 3.70 |

| SD (±x-fold) | 1.33 | 1.34 | 1.40 | 1.43 | 1.44 | 1.38 | 1.47 | 1.46 | 1.54 | 1.72 |

| coeff. of corr. (r) | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.32 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.76 | 0.82 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.86 |

| p-value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.082 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Ranking | geNorm | NormFinder | ΔCt | BestKeeper | RefFinder |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CACS/UBI-1 | CACS | CACS | F-BOX | CACS |

| 2 | - | CYP | CYP | UBI-1 | UBI-1 |

| 3 | CYP | UBI-1 | TIP41-like | HEL | TIP41-like |

| 4 | TIP41-like | TIP41-like | UBI-1 | TIP41-like | F-BOX |

| 5 | F-BOX | F-BOX | F-BOX | CACS | CYP |

| 6 | EF1α | EF1α | UBQ | EF1α | EF1α |

| 7 | UBQ | UBQ | EF1α | UBQ | UBQ |

| 8 | ACT | ACT | ACT | CYP | ACT |

| 9 | GAPDH | GAPDH | GAPDH | ACT | HEL |

| 10 | HEL | HEL | HEL | GAPDH | GAPDH |

| Reference Gene | DEG | Pearson r | p-Value (r) | Spearman ρ | p-Value (ρ) | Lin’s CCC | Scaled RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CACS+UBI-1 | LOX | 0.926 | 1.52 × 10−5 | 0.874 | 3.09 × 10−4 | 0.889 | 0.368 |

| HsfC1 | 0.904 | 5.36 × 10−5 | 0.804 | 2.75 × 10−3 | 0.765 | 0.419 | |

| CYP72A219 | 0.778 | 2.86 × 10−3 | 0.662 | 1.90 × 10−2 | 0.676 | 0.637 | |

| HEL | LOX | 0.760 | 4.12 × 10−3 | 0.706 | 1.33 × 10−2 | 0.387 | 0.663 |

| HsfC1 | 0.784 | 2.52 × 10−3 | 0.671 | 2.04 × 10−2 | 0.773 | 0.629 | |

| CYP72A219 | 0.811 | 1.38 × 10−3 | 0.588 | 4.41 × 10−2 | 0.369 | 0.589 | |

| GAPDH | LOX | 0.414 | 1.81 × 10−1 | 0.329 | 2.96 × 10−1 | 0.168 | 1.040 |

| HsfC1 | 0.495 | 1.02 × 10−1 | 0.601 | 4.28 × 10−2 | 0.485 | 0.962 | |

| CYP72A219 | 0.224 | 4.84 × 10−1 | 0.088 | 7.87 × 10−1 | 0.080 | 1.190 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szczechura, W.; Kłosińska, U.; Nowakowska, M.; Nowak, K.; Nowicki, M. Reliable Gene Expression Normalization in Cucumber Leaves: Identifying Stable Reference Genes Under Drought Stress. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2811. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122811

Szczechura W, Kłosińska U, Nowakowska M, Nowak K, Nowicki M. Reliable Gene Expression Normalization in Cucumber Leaves: Identifying Stable Reference Genes Under Drought Stress. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2811. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122811

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzczechura, Wojciech, Urszula Kłosińska, Marzena Nowakowska, Katarzyna Nowak, and Marcin Nowicki. 2025. "Reliable Gene Expression Normalization in Cucumber Leaves: Identifying Stable Reference Genes Under Drought Stress" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2811. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122811

APA StyleSzczechura, W., Kłosińska, U., Nowakowska, M., Nowak, K., & Nowicki, M. (2025). Reliable Gene Expression Normalization in Cucumber Leaves: Identifying Stable Reference Genes Under Drought Stress. Agronomy, 15(12), 2811. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122811