Optimization of Litchi Fruit Detection Based on Defoliation and UAV

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Implement three defoliation intensities during early fruit development (control: no leaf thinning; moderate: thinning of 6 compound leaves; intensive: thinning of 12 compound leaves), systematically evaluating their comprehensive effects on fruit growth dynamics, yield parameters, quality attributes, and canopy structural reorganization.

- (2)

- Following identification of the optimal intervention level (moderate defoliation), acquire UAV-based imagery of control and moderate defoliation groups to construct a dedicated fruit detection dataset.

- (3)

- Employ a YOLOv8 object detection framework to quantify recognition capability differences across canopy openness treatments.

- (4)

- Investigate synergistic mechanisms between agronomic structural regulation and computer vision perception systems, establishing theoretical foundations and technical pathways for intelligent orchard monitoring frameworks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Experimental Design and Agronomic Trait Quantification

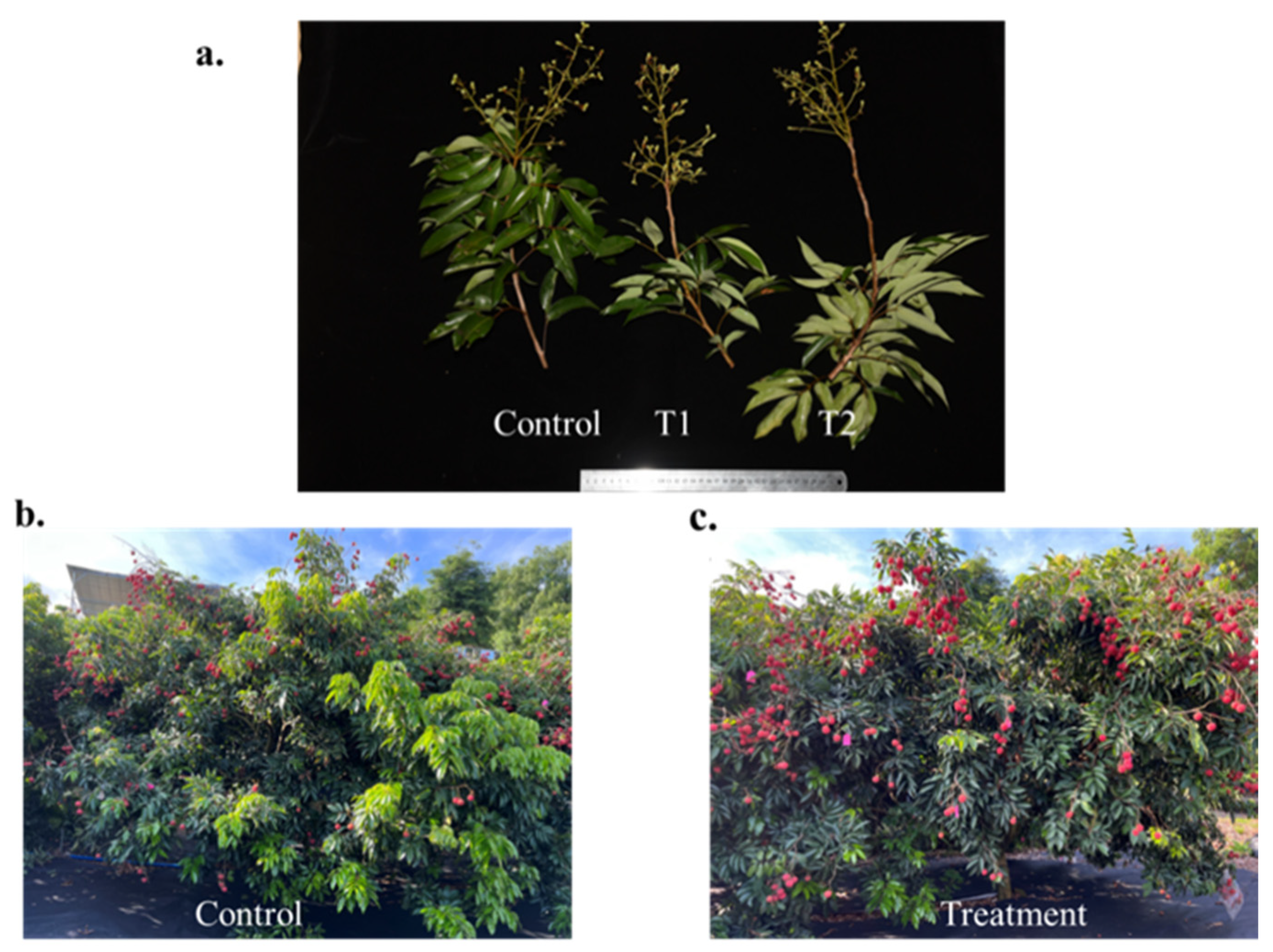

2.1.1. Plant Material Specifications and Experimental Defoliation Design

2.1.2. Determination of Fruit-Related Traits

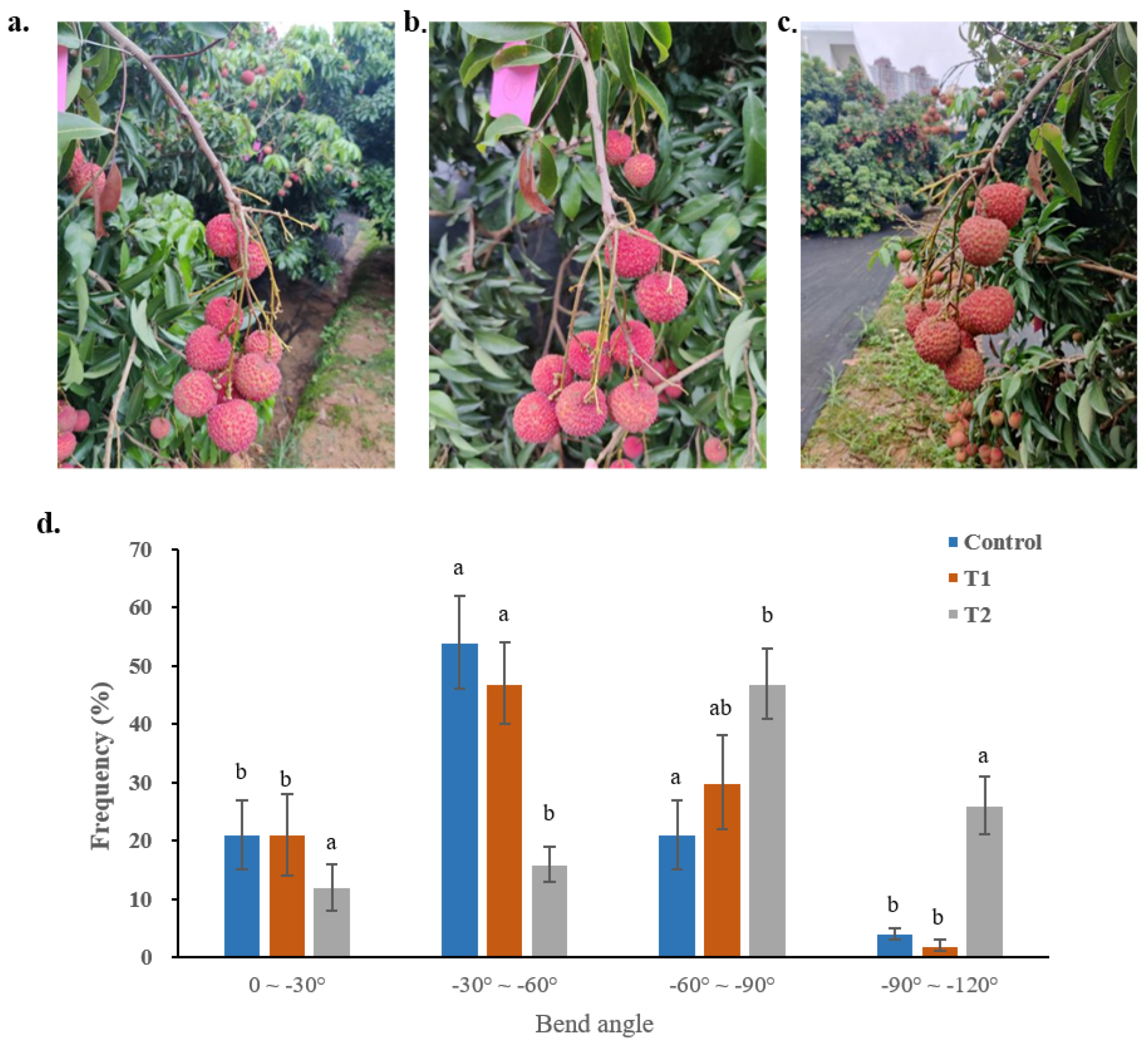

2.1.3. Measurement of Shoot Angle and Canopy Light Permeability

2.1.4. Statistical Analysis

2.2. UAV-Based Image Acquisition and Target Detection

2.2.1. Imaging Platform Deployment and Dataset Construction

2.2.2. YOLO v8 Detection Model

2.2.3. Evaluation Metrics

3. Results

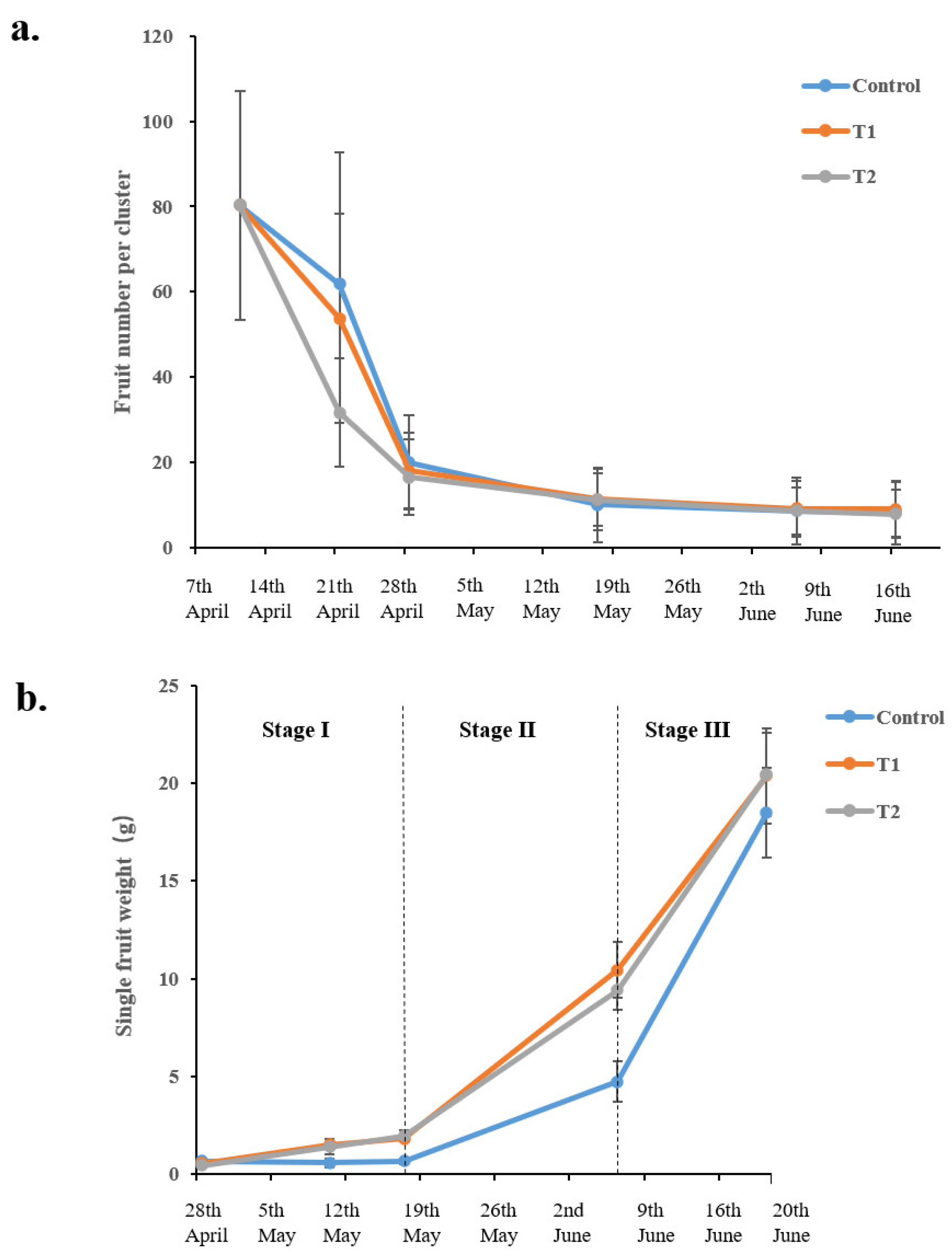

3.1. Fruit Growth Monitoring

3.2. Canopy Structural Dynamics and Light Environment Variation

3.2.1. Shoot Curvature Angle

3.2.2. Canopy Light Intensity and LAI Dynamics

3.3. Fruit Target Detection Performance Analysis

3.3.1. Experimental Configuration

3.3.2. Cross-Model Detection Performance Evaluation

3.3.3. Comparative Analysis of Detection Performance with and Without Defoliation Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qi, W.; Chen, H.; Luo, T.; Song, F. Development status, trend and suggestion of litchi industry in mainland China. Guangdong Agric. Sci. 2019, 46, 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Lin, J.Q.; Li, Z.; Mai, C.D.; Jiang, R.P.; Li, J. An efficient detection method for litchi fruits in a natural environment based on improved YOLOv7-Litchi. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 217, 108605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilaras, A.; Prenafeta-Boldú, F.X. Deep learning in agriculture: A survey. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 147, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbouembe, P.L.T.; Liu, G.; Sikati, J.; Kim, S.C.; Kim, J.H. An efficient tomato detection method based on improved YOLOv4-tiny model in complex environment. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1150958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, I.; Ge, Z.; Dayoub, F.; Upcroft, B.; Perez, T.; McCool, C. Deepfruits: A fruit detection system using deep neural networks. Sensors 2016, 16, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Lan, Y. Fast and precise detection of litchi fruits for yield estimation based on the improved YOLOv5 model. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 965425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. A dragon fruit picking detection method based on YOLOv7 and PSP-Ellipse. Sensors 2023, 23, 3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y. Fruit detection and positioning technology for a Camellia oleifera C. Able orchard based on improved YOLOv4-tiny model and binocular stereo vision. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 211, 118573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolo-Apolo, O.; Martínez-Guanter, J.; Egea, G.; Raja, P.; Pérez-Ruiz, M. Deep learning techniques for estimation of the yield and size of citrus fruits using a UAV. Eur. J. Agron. 2020, 115, 126030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Lv, X.; Lian, X.; Wang, G. YOLOv4_Drone: UAV image target detection based on an improved YOLOv4 algorithm. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2021, 93, 107261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zheng, B.; Chapman, S.C.; Laws, K.; George-Jaeggli, B.; Hammer, G.L.; Jordan, D.; Potgieter, A. Detecting sorghum plant and head features from multispectral UAV imagery. Plant Phenomics 2021, 2021, 9874650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bao, Z.; Qi, J. Seedling maize counting method in complex backgrounds based on YOLOV5 and Kalman filter tracking algorithm. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1030962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zeng, X.; Chen, Y.; Liao, J.; Lai, W.; Zhu, M. An approach to detecting and mapping individual fruit trees integrated YOLOv5 with UAV remote sensing. Preprints 2022, 2022040007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Feng, H.; Fan, Y.; Yue, J.; Yang, F.; Fan, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, R.; Bian, M.; Yang, G. Utilizing UAV-based hyperspectral remote sensing combined with various agronomic traits to monitor potato growth and estimate yield. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 231, 109984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Grimaldo, C.; Nieves, M.; Vera, E.; Duran, M.; Morales, A.; Salazar, W.; Arbizu, C.I. Yield predictions of ‘Del Cerro’cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) germplasm by multispectral monitoring in the north coast of Peru. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2025, 85, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, G.; Matese, A.; Ulrici, A.; Calvini, R.; Berton, A.; Di Gennaro, S.F. Automated yield prediction in vineyard using RGB images acquired by a UAV prototype platform. OENO ONE 2025, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.J.; Liang, J.T.; Yang, W.G.; Ge, W.Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, Z.R.; Bai, S.D.; Fan, J.W.; Lan, Y.B.; Long, Y.B. Enhanced visual detection of litchi fruit in complex natural environments based on unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) remote sensing. Precis. Agric. 2025, 26, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Jiang, W.; Zhao, W.; Zou, L.; Xue, Z. DPD-YOLO: Dense pineapple fruit target detection algorithm in complex environments based on YOLOv8 combined with attention mechanism. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1523552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, T.; Yang, J.; Ma, M. Stff-rtdetr: A small object detection algorithm based on drone aerial photography: X. Teng et al. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnychenko, O.; Scislo, L.; Savenko, O.; Radiuk, P. Intelligent integrated system for fruit detection using multi-UAV imaging and deep learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A.; De Gianni, A.; Previtali, M.A.; Del Nobile, M.A.; Novel, V. Effects of defoliation on quality attributes of Nero di Troia (Vitis vinifera L.) grape and wine. Food Res. Int. 2015, 75, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, N.M.; Yoo, J.; Do, V.G.; Yang, S.; Kwon, S.I.; Kweon, H.J.; Kim, S.; Lee, Y.; Kang, I.K.; Park, J. Effects of pneumatic defoliation on fruit quality and skin coloration in ‘Fuji’Apples. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for realtime object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Maaten, L.V.D.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2261–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Li, J. Molecular events involved in fruitlet abscission in Litchi. Plants 2020, 9, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.G.; Huang, H.; Huang, X. A revised division of the developmental stages in litchi fruit. Yuan Yi Xue Bao 2003, 30, 307–310. [Google Scholar]

- Koirala, A.; Walsh, K.B.; Wang, Z. Attempting to estimate the unseen-correction for occluded fruit in tree fruit load estimation by machine vision with deep learning. Agronomy 2021, 11, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.G.; Zhou, B.Y. Comparison on fruit development and changes in endogenous hormone contents in pericarp between large- and aborted-seeded litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn. cv. Guiwei). Plant Physiol. Com. 2005, 41, 587–590. [Google Scholar]

| Treatment | Yield Per Tree (kg) | Fruit | Seed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Diameter (mm) | Long Transverse Diameter (mm) | Short Transverse Diameter (mm) | Single Fruit Weight (g) | Thickness of Pulp (mm) | TSS | Seed Weight (g) | ||

| Control | 30 | 32.9 | 33.9 | 32.8 | 18.5 b | 10.3 a | 18.94 a | 0.64 c |

| T1 | 37 | 33.3 | 34.7 | 33.5 | 20.4 a | 10.3 a | 18.68 a | 1.25 b |

| T2 | 35 | 32.8 | 34.4 | 32.9 | 20.4 a | 8.2 b | 17.16 b | 2.43 a |

| Precision (P) | Recall (R) | mAP | Inference Time/ms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5 | 0.85 | 0.745 | 0.813 | 172.5 |

| YOLOv7 | 0.833 | 0.808 | 0.826 | 178.6 |

| YOLOv8 | 0.835 | 0.826 | 0.868 | 160.3 |

| Precision (P) | Recall (R) | mAP | F1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.787 | 0.805 | 0.818 | 0.796 |

| T1 | 0.846 | 0.839 | 0.884 | 0.842 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, Z.; Yao, Z.; Nie, B.; Guo, D.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Xiong, J. Optimization of Litchi Fruit Detection Based on Defoliation and UAV. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102421

Wang J, Zhang M, Zheng Z, Yao Z, Nie B, Guo D, Chen L, Li J, Xiong J. Optimization of Litchi Fruit Detection Based on Defoliation and UAV. Agronomy. 2025; 15(10):2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102421

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jing, Mingyue Zhang, Zhenhui Zheng, Zhaoshen Yao, Boxuan Nie, Dongliang Guo, Ling Chen, Jianguang Li, and Juntao Xiong. 2025. "Optimization of Litchi Fruit Detection Based on Defoliation and UAV" Agronomy 15, no. 10: 2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102421

APA StyleWang, J., Zhang, M., Zheng, Z., Yao, Z., Nie, B., Guo, D., Chen, L., Li, J., & Xiong, J. (2025). Optimization of Litchi Fruit Detection Based on Defoliation and UAV. Agronomy, 15(10), 2421. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15102421