Hybrid Biocomposites Based on Chitosan/Gelatin with Coffee Silverskin Extracts as Promising Biomaterials for Advanced Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Coffee-Silverskin Extracts

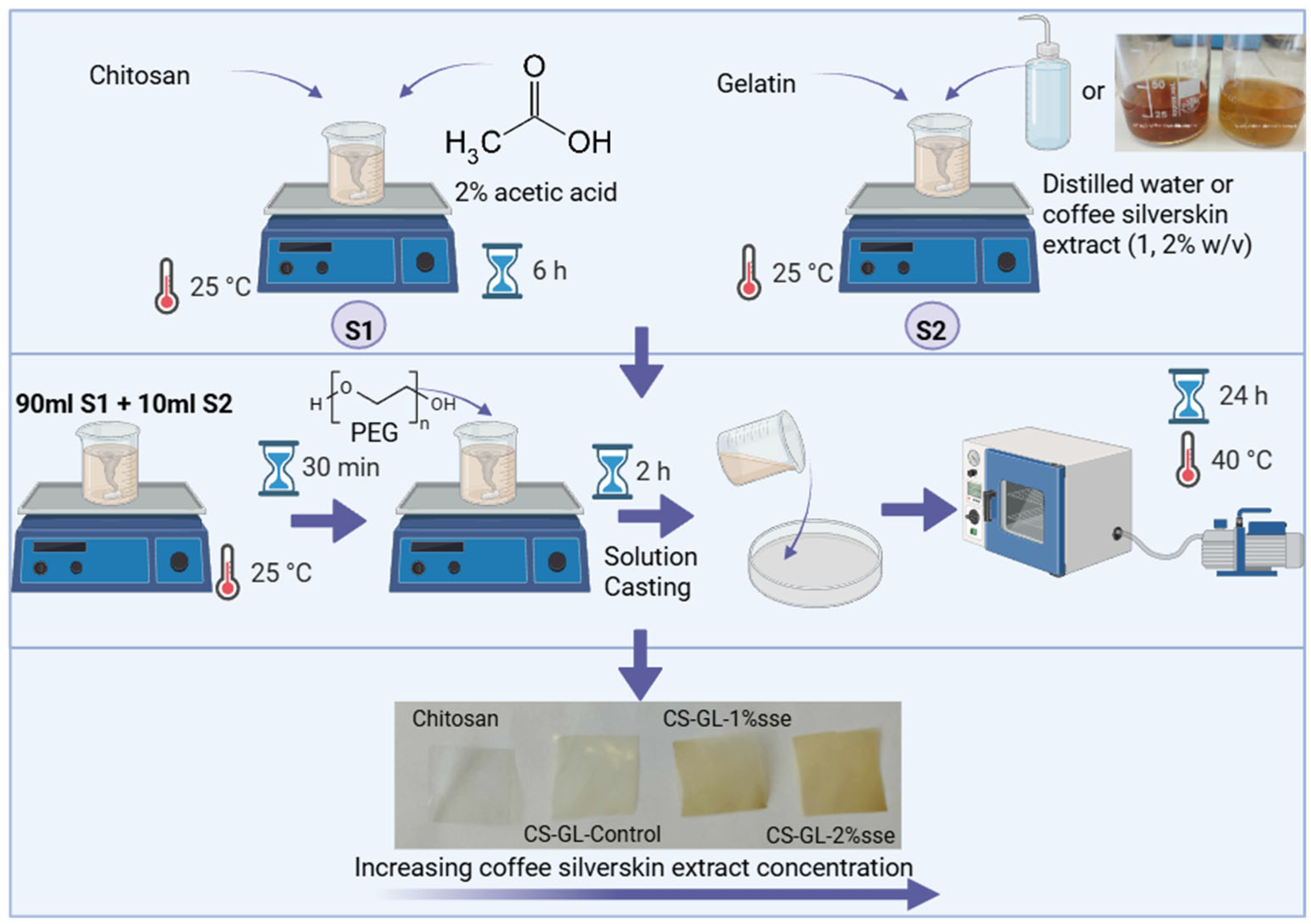

2.3. Preparation of Hybrid Films

2.4. Material Characterization

2.4.1. Chemical Structure and Morphological Characteristics

2.4.2. Physicochemical Properties

2.4.3. Color Measurements

2.4.4. Thermal Properties by Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.4.5. Oxygen and Water Vapor Permeability

2.4.6. Antioxidant Activity

2.4.7. Mechanical Properties

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

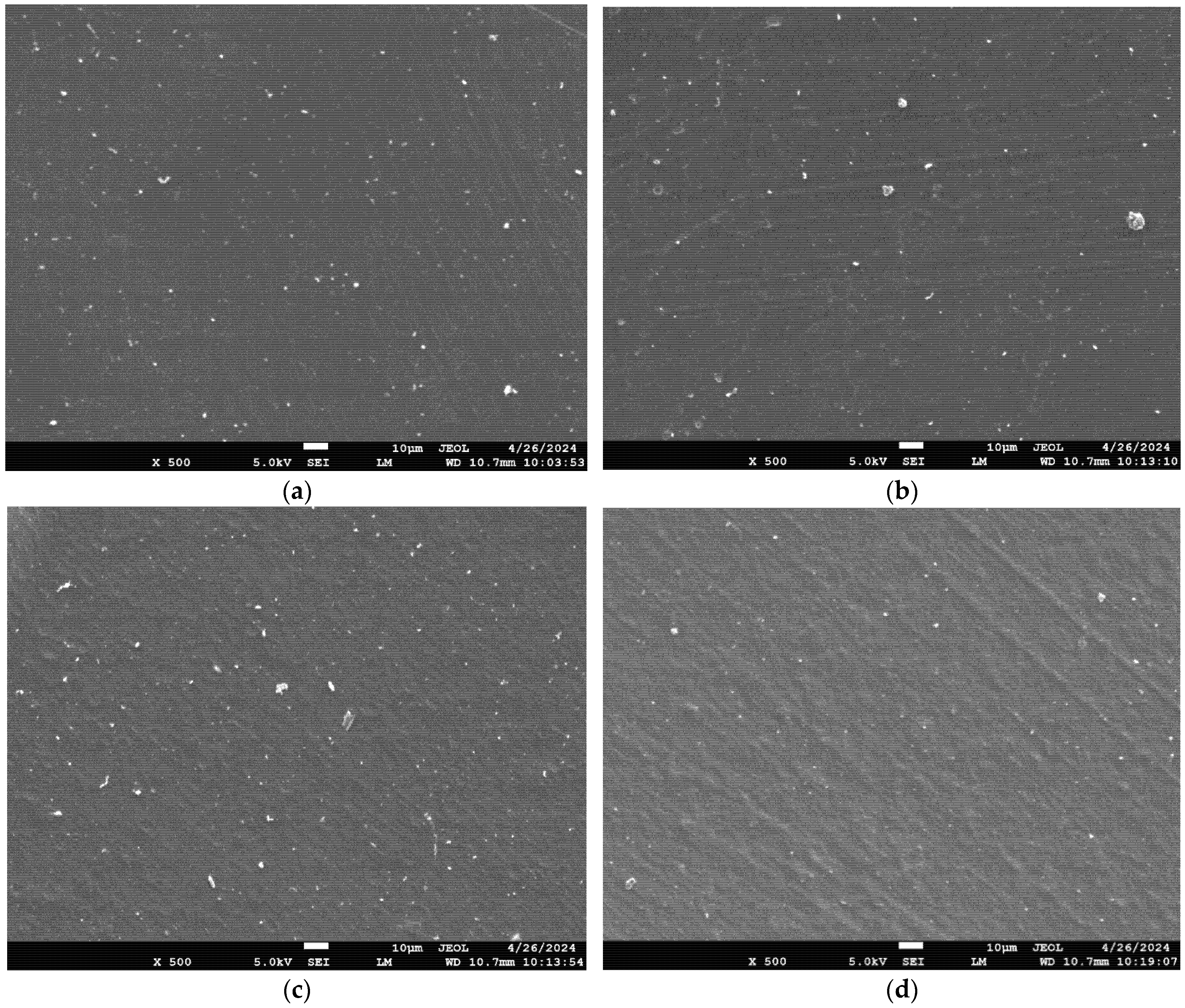

3.1. Morphological Characteristics

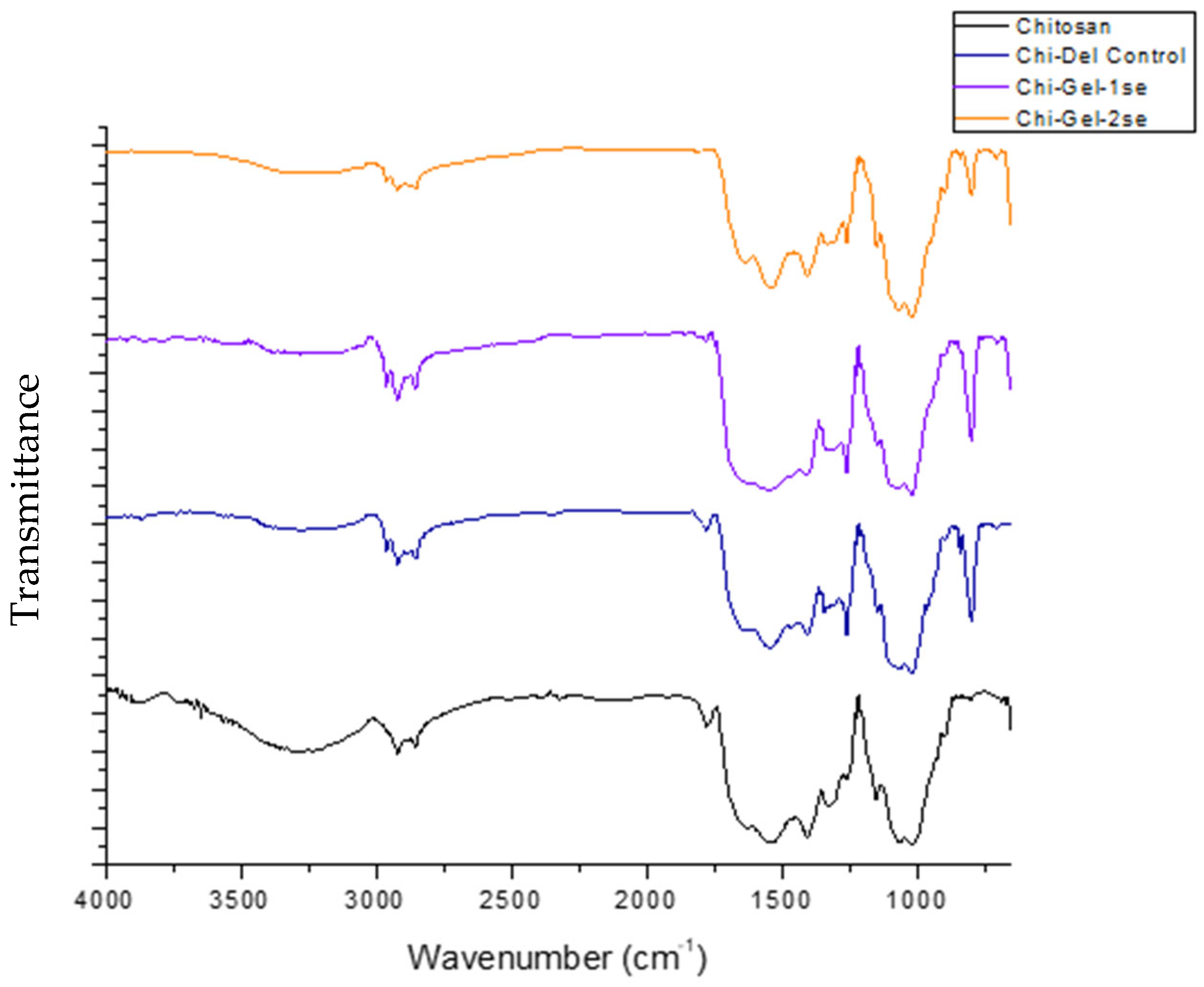

3.2. Chemical Structure

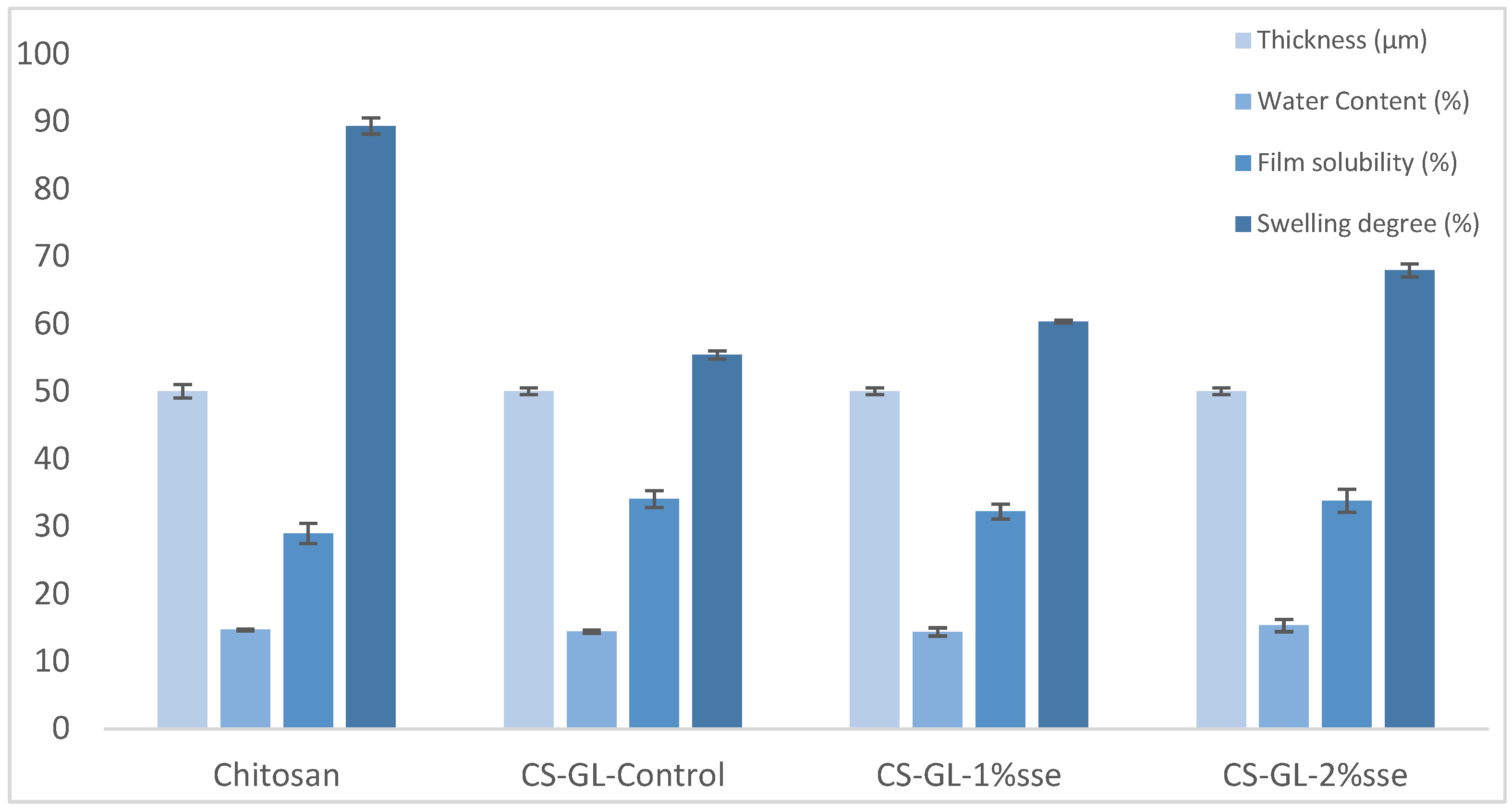

3.3. Physico-Chemical Characterization

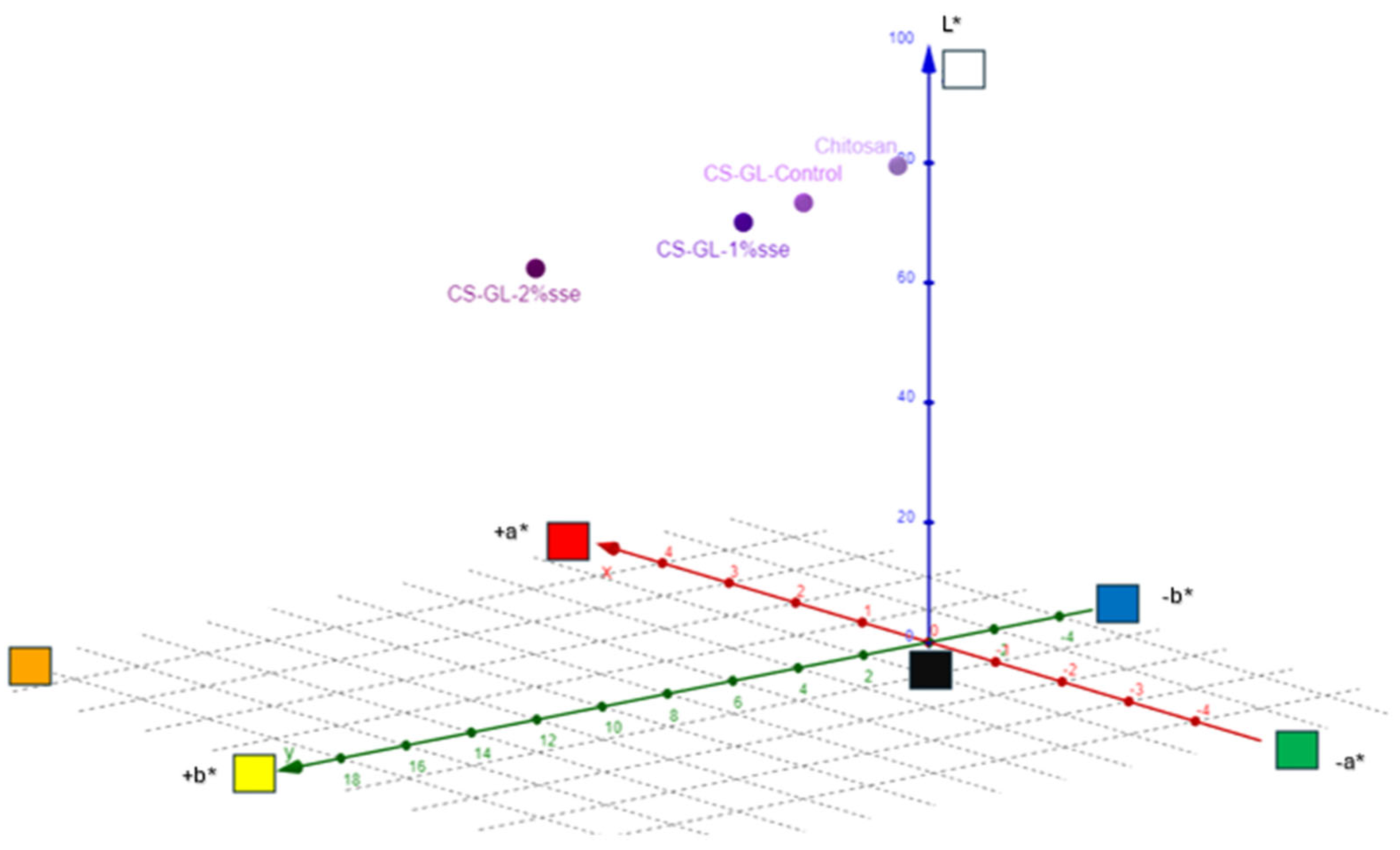

3.4. Color Measurements

3.5. Thermal/Calorimetric Properties

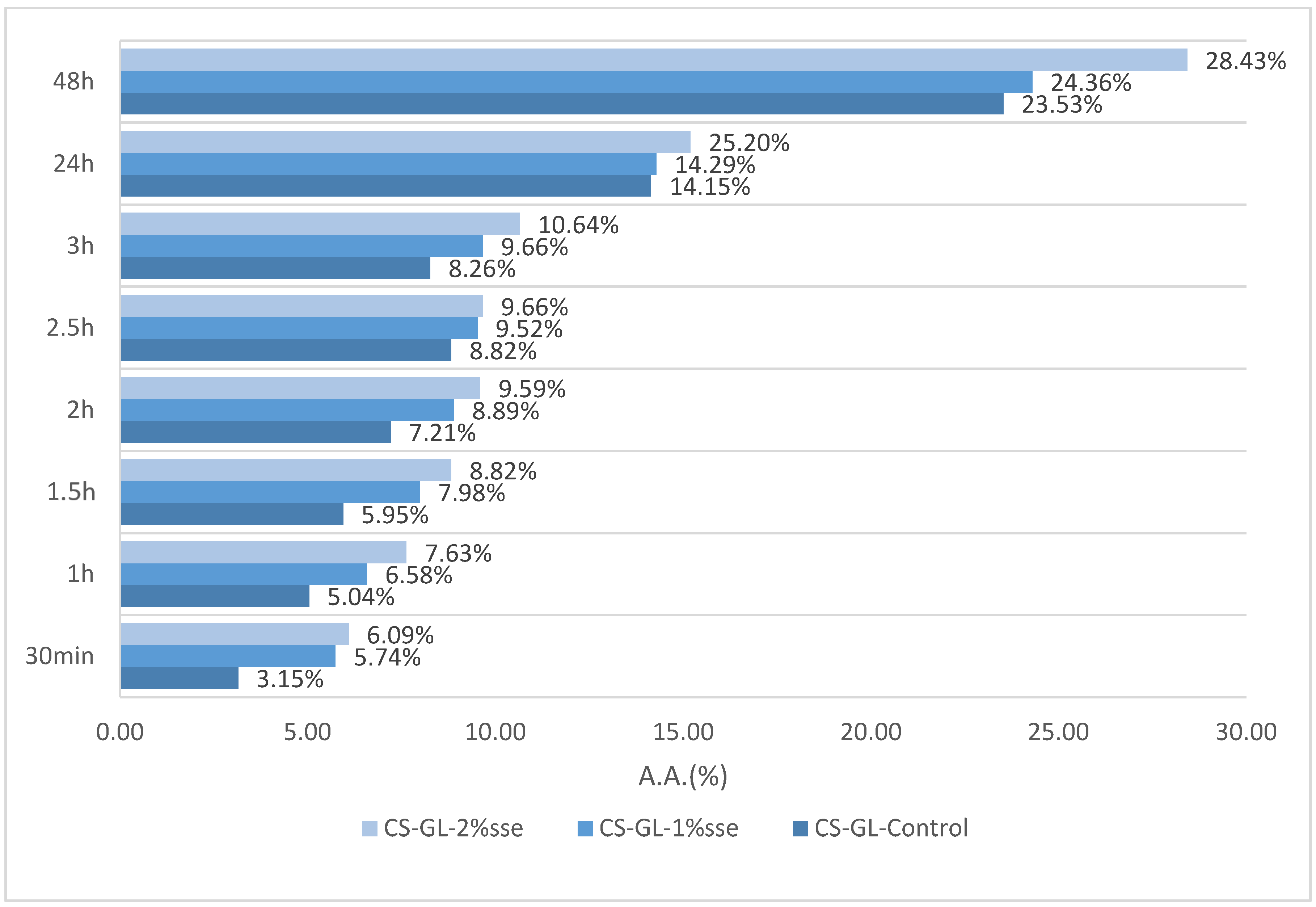

3.6. Antioxidant Activity

3.7. Gas and Water Vapor Permeability

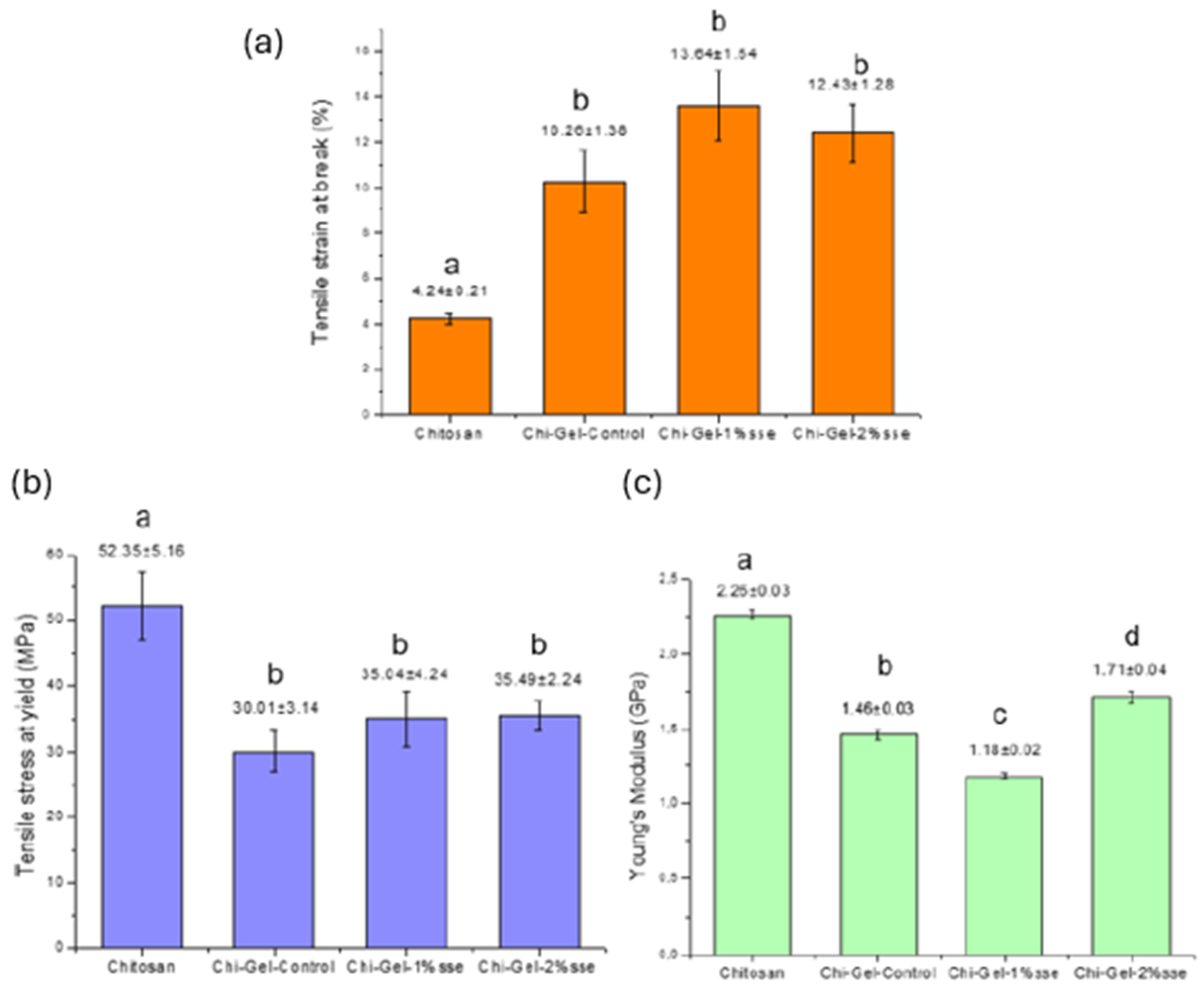

3.8. Mechanical Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, J.W.; Ruiz-Garcia, L.; Qian, J.P.; Yang, X.T. Food Packaging: A Comprehensive Review and Future Trends. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 860–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, M.G.; Sanz, P.D.; López-Carballo, G.; Gavara, R.; Hernández-Muñoz, P. Active edible coating effectiveness in shelf-life enhancement of trout (Oncorhynchusmykiss) fillets. LWT 2015, 60, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasagoudr, S.S.; Hegde, V.G.; Vanjeri, V.N.; Chougale, R.B.; Masti, S.P. Ethyl vanillin incorporated chitosan/poly(vinyl alcohol) active films for food packaging applications. Carbohydr Polym. 2020, 236, 116049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolybaba, M.; Tabil, L.G.; Panigrahi, S.; Crerar, W.J.; Powell, T.; Wang, B. Biodegradable Polymers: Past, Present, and Future. In Proceedings of the ASABE/CSBE North Central Intersectional Meeting, Fargo, ND, USA, 3–4 October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Elsabee, M.Z.; Abdou, E.S. Chitosan based edible films and coatings: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 1819–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.D.; Pérez, L.L.; Salcedo, J.M.; Córdoba, L.P.; Sobral, P.J.D.A. Production and characterization of films based on blends of chitosan from blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) waste and pectin from Orange (Citrus sinensis Osbeck) peel. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 98, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domard, A.; Domard, M. Chitosan: Structure-Properties Relationship and Biomedical Applications, Chapter 9. In Polymeric Biomaterials, Revised and Expanded, 2nd ed.; Dumitriu, S., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, K.; Shahedi, M. Physical, mechanical, and antimicrobial properties of ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer/chitosan/nano-ZnO (ECNZn) nanocomposite films incorporating glycerol plasticizer. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2016, 10, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljawish, A.; Muniglia, L.; Klouj, A.; Jasniewski, J.; Scher, J.; Desobry, S. Characterization of films based on enzymatically modified chitosan derivatives with phenol compounds. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 60, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staroszczyk, H.; Pielichowska, J.; Sztuka, K.; Stangret, J.; Kołodziejska, I. Molecular and structural characteristics of cod gelatin films modified with EDC and TGase. Food Chem. 2012, 130, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shan, P.; Yu, F.; Li, H.; Peng, L. Fabrication and characterization of waste fish scale-derived gelatin/sodium alginate/carvacrol loaded ZIF-8 nanoparticles composite films with sustained antibacterial activity for active food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 230, 123192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Shan, P.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhuang, Y.; Ning, D.; Li, H. Gelatin-based multifunctional composite films integrated with dialdehyde carboxymethyl cellulose and coffee leaf extract for active food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 130302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajput, I.B.; Tareen, F.K.; Khan, A.U.; Ahmed, N.; Khan, M.F.A.; Shah, K.U.; Rahdar, A.; Díez-Pascual, A.M. Fabrication and in vitro evaluation of chitosan-gelatin based aceclofenac loaded scaffold. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 224, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ediyilyam, S.; George, B.; Shankar, S.S.; Dennis, T.T.; Wacławek, S.; Černík, M.; Padil, V.V.T. Chitosan/gelatin/silver nanoparticles composites films for biodegradable food packaging applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, P.K.; Tripathi, S.; Mehrotra, G.K.; Dutta, J. Perspectives for chitosan based antimicrobial films in food applications. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Shukla, A.; Baul, P.P.; Mitra, A.; Halder, D. Biodegradable hybrid nanocomposites of chitosan/gelatin and silver nanoparticles for active food packaging applications. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 16, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, J.; Bittante, A.M.Q.B.; Sobral, P.J.A. Thermal analysis of gelatin–chitosan edible film mixed with plant ethanolic extracts. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 130, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymoorian, M.; Moghimi, R.; Hosseinzadeh, R.; Zandi, F.; Lakouraj, M.M. Fabrication the emulsion-based edible film containing Dracocephalum kotschyi Boiss essential oil using chitosan–gelatin composite for grape preservation. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 7, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilruba Öznur, K.G.; Ayşe Pınar, T.D. Statistical evaluation of biocompatibility and biodegradability of chitosan/gelatin hydrogels for wound-dressing applications. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 1563–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.; Medha Kaith, B.S. A review on chitosan-gelatin nanocomposites: Synthesis, characterization and biomedical applications. React. Funct. Polym. 2022, 179, 105362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, R.; Espinosa-Andrews, H.; Velasquillo-Martínez, C.; García-Carvajal, Z.Y. Composite hydrogels based on gelatin, chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol to biomedical applications: A review. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2020, 69, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Yang, H.; Yang, J.; Peng, M.; Hu, J. Preparation and characterization of chitosan/gelatin/PVA hydrogel for wound dressings. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 146, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, M.A.H.; Islam, J.M.M.; Ahmed, M.; Rahman, M.F.; Ahmed, B. Preparation and characterization of artificial skin using chitosan and gelatin composites for potential biomedical application. Polym. Bull. 2012, 69, 715–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Ni, Y.; Gong, T. Ciprofloxacin-encapsulated sodium alginate, gelatin, and carboxymethyl chitosan hydrogels: A promising platform for localized antibacterial drug delivery. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 3043, 012031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, F.; Wang, K.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H.; Sun, X.; Xie, D. Synthesis, characterizations, and release mechanisms of carboxymethyl chitosan-graphene oxide-gelatin composite hydrogel for controlled delivery of drug. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 155, 110965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Xiao, L. Preparation and characterization of a novel drug delivery system: Biodegradable nanoparticles in thermosensitive chitosan/gelatin blend hydrogels. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A Pure Appl. Chem. 2010, 47, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.S.; Pandey, P.M.; Yogalakshmi, Y.; Banerjee, I.; Al-Zahrani, S.M.; Anis, A.; Pal, K. Synthesis and Assessment of Novel Gelatin–Chitosan Lactate Cohydrogels for Controlled Delivery and Tissue Engineering Applications. Polym.—Plast. Technol. Eng. 2017, 56, 1457–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi-Sefiani, H.; Granados-Carrera, C.M.; Romero García, A.; Chicardi, E.; Domínguez-Robles, J.; Perez-Puyana, V.M. Chitosan–Type-A-Gelatin Hydrogels Used as Potential Platforms in Tissue Engineering for Drug Delivery. Gels 2024, 10, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulawik, P.; Jamróz, E.; Tkaczewska, J.; Vlcko, T.; Zając, M.; Guzik, P.; Janik, M.; Tadele, W.; Golian, J.; Milosavljevic, V. Application of antimicrobial chitosan-Furcellaran-hydrolysate gelatin edible coatings enriched with bioactive peptides in shelf-life extension of pork loin stored at 4 and −20 °C. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254, 127865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanović, J.; Ćirković, J.; Radojković, A.; Mutavdžić, D.; Stanojević, G.; Joksimović, K.; Bakić, G.; Brankovič, G.; Branković, Z. Chitosan and pectin-based films and coatings with active components for application in antimicrobial food packaging. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 158, 106349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, J.; Sobral, P.J.A. Investigation of the physicochemical, antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of gelatin-chitosan edible film mixed with plant ethanolic extracts. Food Biosci. 2016, 16, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wen, X.L.; Guo, S.G.; Chen, M.T.; Jiang, A.M.; Lai, L.S. Physical, antioxidant and structural characterization of blend films based on hsian-tsao gum (HG) and casein (CAS). Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 134, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, P.; Jiménez, V.M. Functional properties of coffee and coffee by-products. Food Res. Int. 2012, 46, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.C.; Rodrigues, F.; Nunes, M.A.; Vinha, A.F.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. State of the art in coffee processing by-products. In Handbook of Coffee Processing By-Products: Sustainable Applications; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.S.G.; Alves, R.C.; Vinha, A.F.; Barreira, S.V.; Nunes, M.A.; Cunha, L.M.; Oliveira, M.B.P. Optimization of antioxidants extraction from coffee silverskin, a roasting by-product, having in view a sustainable process. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 53, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, P.M.; Mujeeb, V.M.A.; Muraleedharan, K. Flexible chitosan-nano ZnO antimicrobial pouches as a new material for extending the shelf life of raw meat. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 97, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Ikram, S. Chitosan and gelatin based biodegradable packaging films with UV-light protection. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 163, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhshizadeh, M.; Ayaseh, A.; Hamishehkar, H.; Kafil, H.S.; Moghaddam, T.N.; Haghi, P.B.; Tavassoli, M.; Amjadi, S.; Lorenzo, J.M. Designing a multifunctional packaging system based on gelatin/alove vera gel film containing of rosemary essential oil and common poppy anthocyanins. Res. Sq. 2023, 154, 110017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Song, X.; Li, Y. Antimicrobial, physical and mechanical properties of kudzu starch-chitosan composite films as a function of acid solvent types. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 84, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.A.; Bierhalz, A.C.K.; Kieckbusch, T.G. Alginate and pectin composite films crosslinked with Ca2+ ions: Effect of the plasticizer concentration. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 77, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y. Development of tea extracts and chitosan composite films for active packaging materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 59, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An Outline of Standard ASTM E96 for Cup Method Water Vapor Permeability Testing. Available online: https://en.labthink.com/en-us/literatures/an-outline-of-standard-for-cup-method-water-vapor-permeability-testing.html (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- ASTM D 882; Tensile Testing of Thin Plastic Sheeting. Instron: Norwood, MA, USA, 2005.

- Silva, S.S.; Goodfellow, B.J.; Benesch, J.; Rocha, J.; Mano, J.F.; Reis, R.L. Morphology and miscibility of chitosan/soy protein blended membranes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 70, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shajahan, A.; Sathiyaseelan, A.; Narayan, K.; Narayanan, V. Preparation of Nanocomposite Based Film from Fungal Chitosan and Its Applications. 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273453610 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Martins, J.T.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Vicente, A.A. Influence of α-tocopherol on physicochemical properties of chitosan-based films. Food Hydrocoll. 2012, 27, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivanovic, S.; Basurto, C.C.; Chi, S.; Davidson, P.M.; Weiss, J. Molecular Weight of Chitosan Inn uences Antimicrobial Activity in Oil-in-Water Emulsions. J. Food Prot. 2004, 67, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.L.; Ferreira, M.C.; Marvão, M.R.; Rocha, J. An Optimised Method to Determine the Degree of Acetylation of Chitin and Chitosan by FTIR Spectroscopy. 2002. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/locate/ijbiomac (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Uchida, Y.; Lzume, M.; Ohtakara, A. Preparation of chitosan oligomers with purified chitosanase and its application. In Chitin and Chitosan: Sources, Chemistry, Biochemistry, Physical Properties and Applications; Skjak-Brak, G., Anthonsen, T., Sandford, P.A., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 1989; pp. 373–382. [Google Scholar]

- Pereda, M.; Ponce, A.G.; Marcovich, N.E.; Ruseckaite, R.A.; Martucci, J.F. Chitosan-gelatin composites and bi-layer films with potential antimicrobial activity. Food Hydrocoll. 2011, 25, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Cheng, L.; Song, X.; Gao, Q. Functional properties and characterization of maize starch films blended with chitosan. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2023, 36, 4977–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Dong, Y.; Men, H.; Tong, J.; Zhou, J. Preparation and characterization of active films based on chitosan incorporated tea polyphenols. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 32, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pierro, P.; Chico, B.; Villalonga, R.; Mariniello, L.; Damiao, A.E.; Masi, P.; Porta, R. Chitosan-whey protein edible films produced in the absence or presence of transglutaminase: Analysis of their mechanical and barrier properties. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Ó.L.; Reinas, I.; Silva, S.I.; Fernandes, J.C.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Pereira, R.N.; Vicente, A.A.; Poças, M.F.; Pintado, M.E.; Malcata, F.X. Effect of whey protein purity and glycerol content upon physical properties of edible films manufactured therefrom. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 30, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraczewski, K.; Pawłowska, A.; Stepczyńska, M.; Malinowski, R.; Kaczor, D.; Budner, B.; Gocman, K.; Rytlewski, P. Plant extracts as natural additives for environmentally friendly polylactide films. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 26, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeleine-Perdrillat, C.; Karbowiak, T.; Debeaufort, F.; Delmotte, L.; Vaulot, C.; Champion, D. Effect of hydration on molecular dynamics and structure in chitosan films. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 61, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffey, A.; Glasser, W.G. Chitin derivatives III Formation of amidized homologs of chitosan. Cellulose 2001, 8, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, J.; Fortunati, E.; Atarés, L.; Chiralt, A.; Kenny, J.M. Physical, structural and antimicrobial properties of poly vinyl alcohol-chitosan biodegradable films. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 35, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittur, F.S.; Prashanth, K.V.H.; Sankar, K.U.; Tharanathan, R.N. Characterization of Chitin, Chitosan and Their Carboxymethyl Derivatives by Differential Scanning Calorimetry. 2002. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/locate/carbpol (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Giannakas, A. Na-montmorillonite vs. organically modified montmorillonite as essential oil nanocarriers for melt-extruded low-density poly-ethylene nanocomposite active packaging films with a controllable and long-life antioxidant activity. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Estaca, J.; López-de-Dicastillo, C.; Hernández-Muñoz, P.; Catalá, R.; Gavara, R. Advances in antioxidant active food packaging. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 35, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriondo-DeHond, A.; Martorell, P.; Genovés, S.; Ramón, D.; Stamatakis, K.; Fresno, M.; Molina, A.; Del Castillo, M.D. Coffee silverskin extract protects against accelerated aging caused by oxidative agents. Molecules 2016, 21, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasini, F.; Tirillò, J.; Zuorro, A.; Maffei, G.; Lavecchia, R.; Puglia, D.; Dominici, F.; Luzi, F.; Valente, T.; Torre, L. Recycling coffee silverskin in sustainable composites based on a poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) matrix. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 118, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzekoue, F.K.; Angeloni, S.; Navarini, L.; Angeloni, C.; Freschi, M.; Hrelia, S.; Vitali, L.A.; Sagratini, G.; Vittori, S.; Caprioli, G. Coffee silverskin extracts: Quantification of 30 bioactive compounds by a new HPLC-MS/MS method and evaluation of their antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Food Res. Int. 2020, 133, 109128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Qin, Y.; Liu, J. Effects of anthocyanin-rich purple and black eggplant extracts on the physical, antioxidant and pH-sensitive properties of chitosan film. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 94, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejna, A.; Barczewski, M.; Kosmela, P.; Mysiukiewicz, O.; Kuzmin, A. Coffee silverskin as a multifunctional waste filler for high-density polyethylene green composites. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.A.; Martino, M.N.; Zaritzky, N.E. Lipid addition to improve barrier properties of edible starch-based films and coatings. J. Food Sci. 2000, 65, 941–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.; Osés, J.; Ziani, K.; Maté, J.I. Combined effect of plasticizers and surfactants on the physical properties of starch based edible films. Food Res. Int. 2006, 39, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sothornvit, R.; Pitak, N. Oxygen permeability and mechanical properties of banana films. Food Res. Int. 2007, 40, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasa, P.C.; Ramesh, M.N.; Tharanathan, R.N. Effect of plasticizers and fatty acids on mechanical and permeability characteristics of chitosan films. Food Hydrocoll. 2007, 21, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mitra, A.; Halder, D. Centella asiatica leaf mediated synthesis of silver nanocolloid and its application as filler in gelatin based antimicrobial nanocomposite film. LWT 2017, 75, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Almeida, M.; Pereira, L.; Costa, C. Linden-based mucilage biodegradable films: A green perspective on functional and sustainable food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 260, 129805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilican, I.; Pekdemir, S.; Onses, M.S.; Akyuz, L.; Altuner, E.M.; Koc-Bilican, B.; Zang, L.S.; Mujtaba, M.; Mulerčikas, P.; Kaya, M. Chitosan Loses Innate Beneficial Properties after Being Dissolved in Acetic Acid: Supported by Detailed Molecular Modeling. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 18083–18093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chitosan | Chi-Gel-Control | Chi-Gel-1%sse | Chi-Gel-2%sse | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physico-chemical characterization | ||||

| Τhickness (μm) | 50 ± 1.0 | 50 ± 0.5 | 50 ± 0.5 | 50 ± 0.5 |

| Water content (%) | 14.67 ± 0.14 a | 14.43 ± 0.24 a | 14.36 ± 0.61 a | 15.31 ± 0.90 a |

| Film solubility (%) | 28.92 ± 1.49 A | 34.05 ± 1.24 B | 32.3 ± 1.09 B | 33.79 ± 1.73 B |

| Swelling degree (%) | 89.33 ± 1.19 α | 55.39 ± 0.59 β | 60.32 ± 0.21 γ | 67.91 ± 0.98 δ |

| Color measurements | ||||

| L* | 90.65 | 87.87 | 86.46 | 85.47 |

| a* | −1.84 | −1.89 | −1.87 | −1.84 |

| b* | 4.7 | 7.69 | 9.49 | 15.79 |

| c* | 5.05 | 7.91 | 9.65 | 16.03 |

| h | 111.4 | 100 | 100.4 | 103.6 |

| R% (400 nm) | 63.05 | 44.99 | 48.82 | 48.16 |

| K/S | 0.11 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.28 |

| Thermal properties | ||||

| Tg (°C) (1st heat) | 97.53 | 94.62 | 95.18 | 93.82 |

| Tm (°C) (1st heat) | 126.04 | - | - | - |

| DH (J/g) (1st heat) | 677.85 | - | - | - |

| Tcc (°C) (cooling) | - | −23.58 | −17.95 | −15.13 |

| DH (J/g) (cooling) | - | −15.27 | −15.87 | −13.85 |

| Tm (°C) (2nd heat) | - | 50.24 | 51.47 | 52.03 |

| DH (J/g) (2nd heat) | - | 16.33 | 21.54 | 20.60 |

| Permeability properties | ||||

| WVTR (g/m2∙d) | 14.01 | 13.69 | 13.52 | 13.69 |

| WVP (10−7) (g/m∙d∙Pa) | 2.99 | 2.93 | 2.89 | 2.93 |

| OTR(cm3/(m2∙d∙0.1 MPa) | 7.50 | 6.60 | 4.74 | 3.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petaloti, A.-I.; Achilias, D.S. Hybrid Biocomposites Based on Chitosan/Gelatin with Coffee Silverskin Extracts as Promising Biomaterials for Advanced Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 3194. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233194

Petaloti A-I, Achilias DS. Hybrid Biocomposites Based on Chitosan/Gelatin with Coffee Silverskin Extracts as Promising Biomaterials for Advanced Applications. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3194. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233194

Chicago/Turabian StylePetaloti, Argyri-Ioanna, and Dimitris S. Achilias. 2025. "Hybrid Biocomposites Based on Chitosan/Gelatin with Coffee Silverskin Extracts as Promising Biomaterials for Advanced Applications" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3194. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233194

APA StylePetaloti, A.-I., & Achilias, D. S. (2025). Hybrid Biocomposites Based on Chitosan/Gelatin with Coffee Silverskin Extracts as Promising Biomaterials for Advanced Applications. Polymers, 17(23), 3194. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233194