Macromolecular and Supramolecular Organization of Ionomers

Abstract

1. The Basic Characteristics of Ionomers

Application of Ionomers

2. Anionic Ionomers

2.1. Sulfonic Acid-Based Ionomers

2.2. Carboxylic Acid-Based Ionomers

2.3. Phosphoric and Phosphonic Acid-Based Ionomers

3. Cationic Ionomers

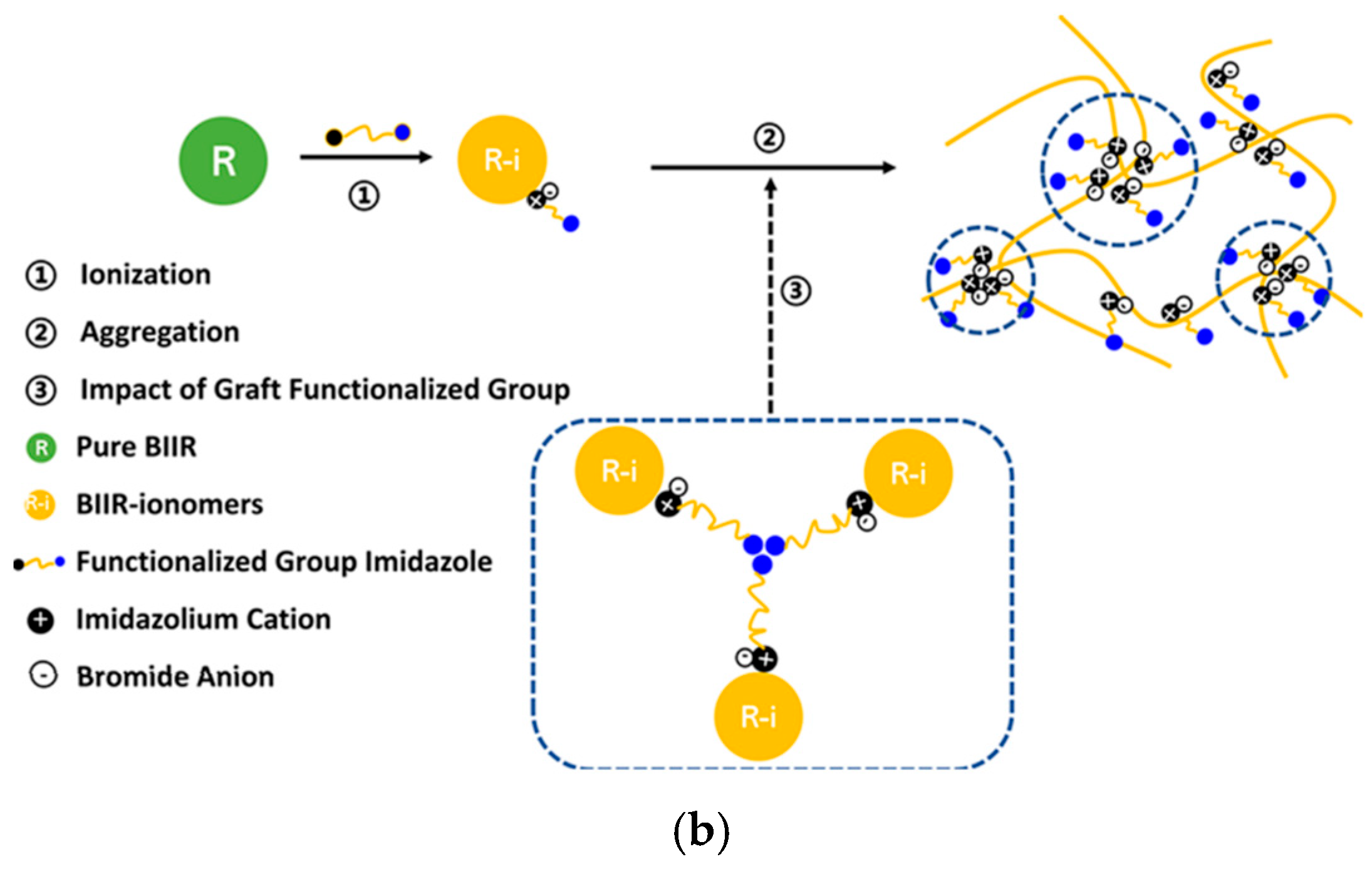

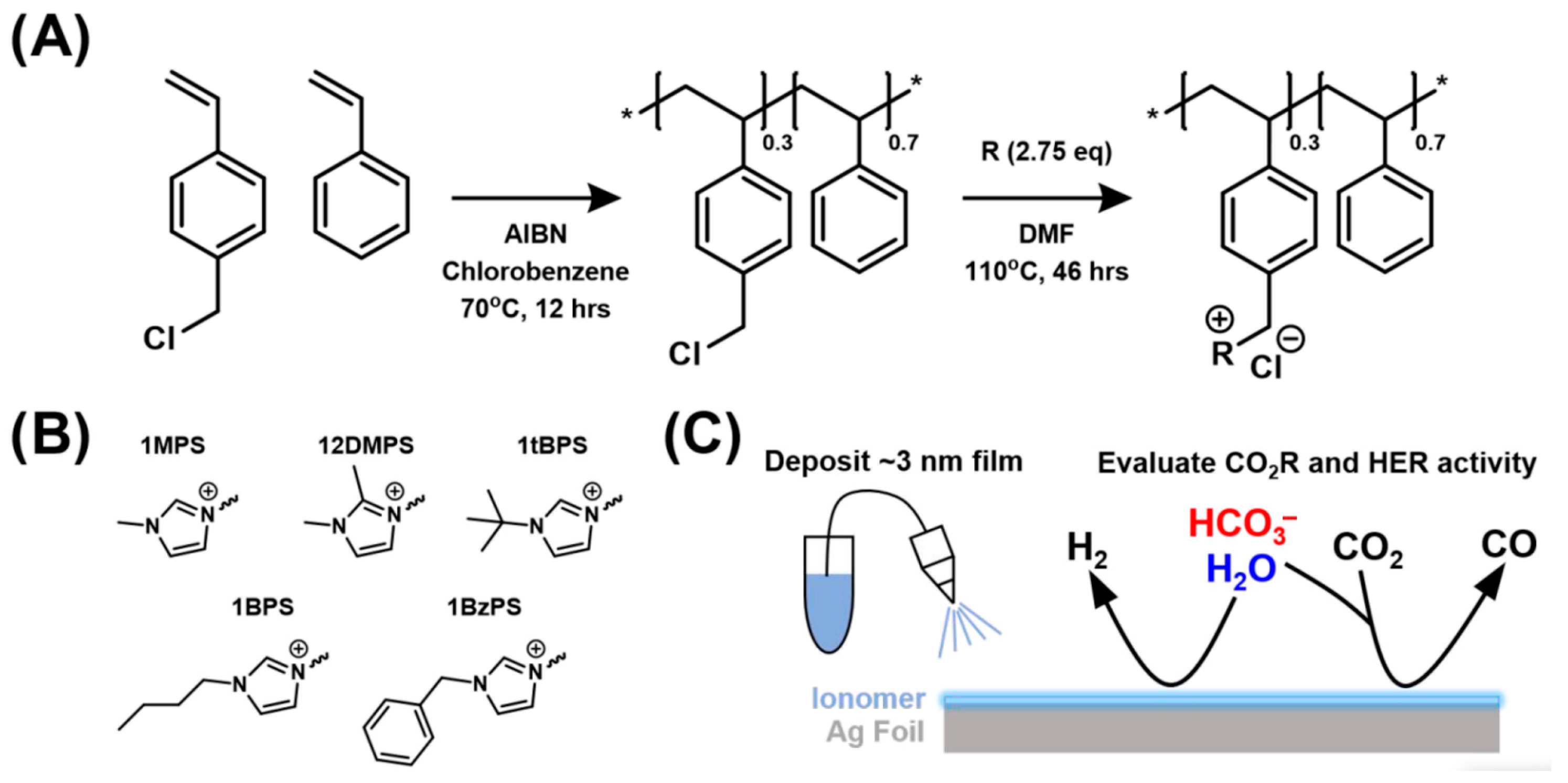

3.1. Imidazolium-Based Ionomers

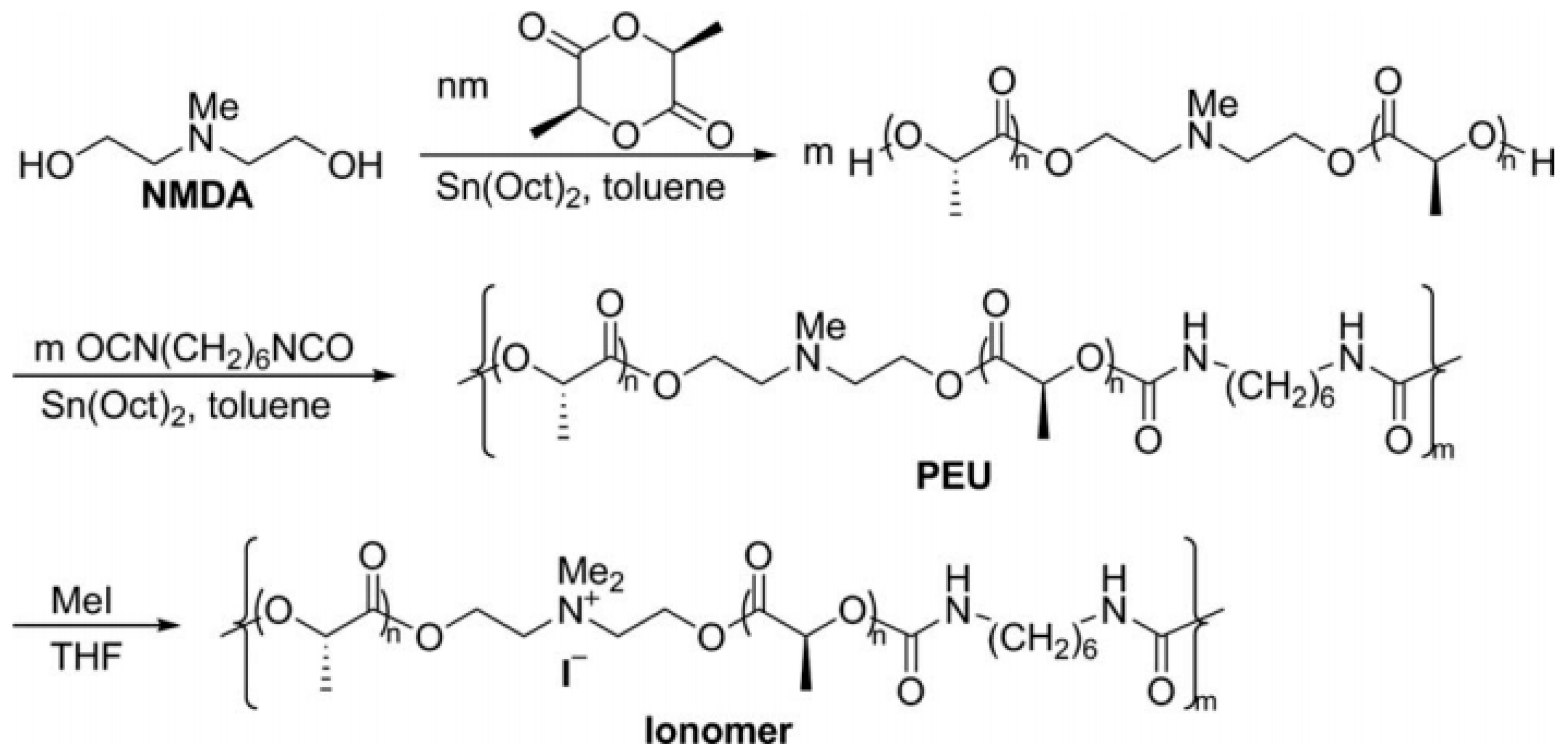

3.2. Quaternary Ammonium-Based Ionomers

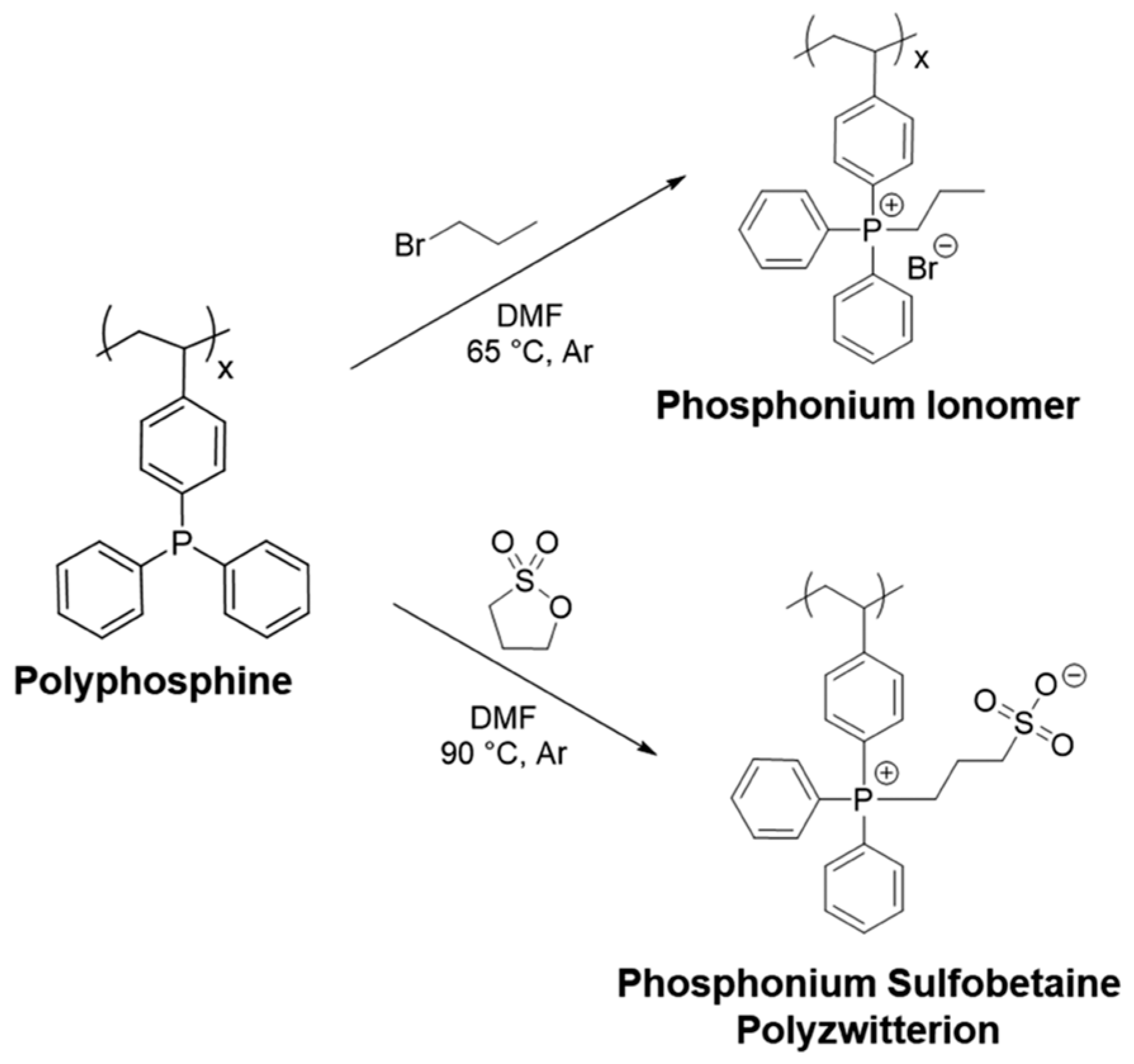

3.3. Prospects for the Synthesis Strategy of Cationic Ionomers

4. Discussion and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Potaufeux, J.-E.; Odent, J.; Notta-Cuvier, D.; Lauro, F.; Raquez, J.-M. A comprehensive review of the structures and properties of ionic polymeric materials. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 5914–5936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, R.W.; Vaughan, D.J. «Surlyn» A Ionomers: I. The Effects of Ionic Bonding on Polymer Structure. Polym. Prepr. (Am. Chem. Soc. Div. Polym. Chem.) 1965, 6, 287–295. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Li, G. One-Way Multishape-Memory Effect and Tunable Two-Way Shape Memory Effect of Ionomer Poly(ethylene-co-methacrylic acid). ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 14812–14823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, R.J.; Zwaag, S. Towards an Understanding of Thermally Activated Self-Healing of an Ionomer System During Ballistic Penetration. Acta Mater. 2008, 56, 5737–5750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.K.; Paul, D.R. Comparison of Nanocomposites Prepared from Sodium, Zinc, and Lithium Ionomers of Ethylene/Methacrylic Acid Copolymers. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 3327–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwaag, S. Self-Healing Materials: An Alternative Approach to 20 Centuries of Materials Science; Springer Science + Business Media B.V.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; p. 388. [Google Scholar]

- Kalista, S.J., Jr.; Pflug, J.R.; Varley, R.J. Effect of Ionic Content on Ballistic Self-Healing in EMAA Copolymers and Ionomers. Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 4910–4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Li, J.; Zhao, Q. Hidden Thermoreversible Actuation Behavior of Nafion and Its Morphological Origin. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, R.R.; Lor, M.; Chen, J. Remote, Local, and Chemical Programming of Healable Multishape Memory Polymer Nanocomposites. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 2757–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.-Y.; Li, Y.-C.; Liu, J.; He, J.; Wang, L.-Y.; Lei, J.-D. Recent Developments in High-Performance Nafion Membranes for Hydrogen Fuel Cells Applications. Pet. Sci. 2022, 19, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.H.; Neidhart, E.K.; Sheiko, S.S.; Bras, W.; Leibfarth, F.A. Polyolefin Ionomer Synthesis Enabled by C–H Thioheteroarylation. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 8920–8927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, R.D. Structure and Properties of Ionomers; Pineri, M., Eisenberg, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1987; Volume 198, pp. 429–446. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Tan, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X. Supramolecular Polymers: Historical Development, Preparation, Characterization, and Functions. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7196–7239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmeier, H.; Schubert, U.S. Combination of Orthogonal Supramolecular Interactions in Polymeric Architectures. Chem. Commun. 2005, 19, 2423–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, C.M. Protein Folding and Misfolding. Am. Sci. 2002, 90, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.J.; Mio, M.J.; Prince, R.B.; Hughes, T.S.; Moore, J.S. A Field Guide to Foldamers. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 3893–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, P.; Wagener, K.B.; Schulz, M.D. ADMET: The Future Revealed. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 4735–4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines, T.W.; Trigg, E.B.; Winey, K.I.; Wagener, K.B. High Melting Precision Sulfone Polyethylenes Synthesized by ADMET Chemistry. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2016, 217, 2351–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caire da Silva, L.; Rojas, G.; Schulz, M.D.; Wagener, K.B. Acyclic Diene Metathesis Polymerization: History, Methods and Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2017, 69, 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughman, T.; Chan, C.; Winey, K.; Wagener, K.B. Synthesis and Morphology of Well-Defined Poly(ethylene-co-acrylic acid) Copolymers. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 6564–6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denissen, W.; Winne, J.M.; Du Prez, F.E. Vitrimers: Permanent Organic Networks with Glass-like Fluidity. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelot, M.; Unterlass, M.M.; Tournilhac, F.; Leibler, L. Catalytic Control of the Vitrimer Glass Transition. ACS Macro Lett. 2012, 1, 789–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Cao, P.-F.; Saito, T.; Sokolov, A.P. Intrinsically Self-Healing Polymers: From Mechanistic Insight to Current Challenges. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 701–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabiso, W.; Schlögl, S. The Impact of Vitrimers on the Industry of the Future: Chemistry, Properties and Sustainable Forward-Looking Applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, N.; Fang, Z.; Zou, W.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, T. Thermoset Shape-Memory Polyurethane with Intrinsic Plasticity Enabled by Transcarbamoylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11421–11425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wei, Y.; Ji, Y. Regional Shape Control of Strategically Assembled Multishape Memory Vitrimers. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, J.J.; Kubo, T.; Bapat, A.P.; Sumerlin, B.S. Room-Temperature Self-Healing Polymers Based on Dynamic-Covalent Boronic Esters. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 2098–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.; Feig, V.R.; Liu, K.; Zheng, Y.; Bao, Z. Polymer Chemistries Underpinning Materials for Skin-Inspired Electronics. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 3965–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; Zhang, Z.P.; Rong, M.Z.; Zhang, M.Q. Tailored Modular Assembly Derived Self-Healing Polythioureas with Largely Tunable Properties Covering Plastics, Elastomers and Fibers. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloxin, C.J.; Bowman, C.N. Covalent Adaptable Networks: Smart, Reconfigurable and Responsive Network Systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7161–7173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Lei, Z.; Taynton, P.; Huang, S.; Zhang, W. Malleable and Recyclable Thermosets: The Next Generation of Plastics. Matter 2019, 1, 1456–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhu, S.; Guo, Y.; Tang, H.; Yang, D.; Zhang, C.; Ming, P.; Li, B. Control of Cluster Structures in Catalyst Inks by a Dispersion Medium. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 32960–32969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.; Shi, A.-C.; An, L. Formation of Ionomer Microparticles via Polyelectrolyte Complexation. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 9053–9062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, S.J.; Cantrill, S.J.; Cousins, G.R.L.; Sanders, J.K.M.; Stoddart, J.F. Dynamic Covalent Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 898–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordier, P.; Tournilhac, F.; Soulie-Ziakovic, C.; Leibler, L. Self-Healing and Thermoreversible Rubber from Supramolecular Assembly. Nature 2008, 451, 977–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Greef, T.F.A.; Smulders, M.M.J.; Wolffs, M.; Schenning, A.P.H.J.; Sijbesma, R.P.; Meijer, E.W. Supramolecular Polymerization. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 5687–5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangizehi, A.; Ghaffarian, S.R.; Ahmadi, M. Dynamics of entangled supramolecular polymer networks in presence of high-order associations of strong hydrogen bonding groups Polym. Adv. Technol. 2018, 29, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Jangizehi, A.; Ruymbeke, E.; Seiffert, S. Deconvolution of the Effects of Binary Associations and Collective Assemblies on the Rheological Properties of Entangled Side-Chain Supramolecular Polymer Networks. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 5255–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, A. Clustering of Ions in Organic Polymers. A Theoretical Approach. Macromolecules 1970, 3, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, A.; Rinaudo, M. Polymer Bulletin. Polym. Bull. 1990, 24, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, A.; Hird, B.; Moore, R.B. A New Multiplet-Cluster Model for the Morphology of Random Ionomers. Macromolecules 1990, 23, 4098–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Sprenger, C.; Pareras, G.; Poater, A.; Seiffert, S. Self-organization of metallo-supramolecular polymer networks by free formation of pyridine–phenanthroline heteroleptic complexes. Soft Matter 2023, 19, 8112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradinik, N.; Mohammadi, E.; Yavitt, B.M.; Schafer, L.L.; Hatzikiriakos, S.G. Impact of Quenching Agents on Internal Associations and Structure of Amine-Functionalized Polyolefins. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 7836–7847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Bauer, M.; Berg, J.; Seiffert, S. Nonuniversal Dynamics of Hyperbranched Metallo-Supramolecular Polymer Networks by the Spontaneous Formation of Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 29282–29293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

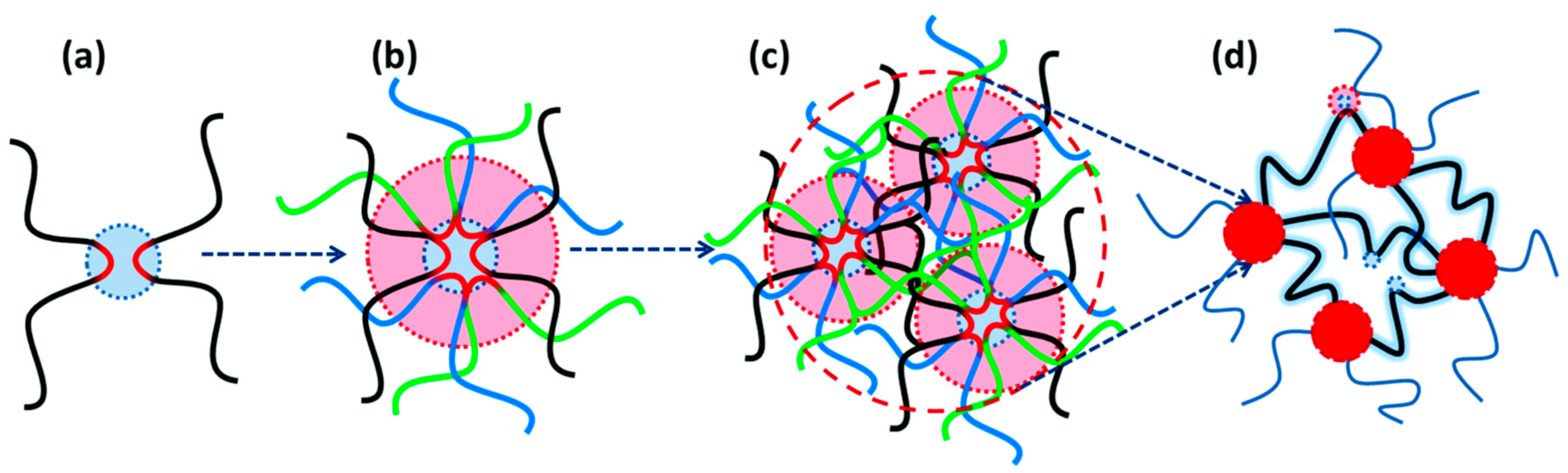

- Jangizehi, A.; Ahmadi, M.; Seiffert, S. Emergence, evidence, and effect of junction clustering in supramolecular polymer materials. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tant, M.R.; Mauritz, K.A.; Wilkes, G.L. Ionomers: Synthesis, Structure, Properties, and Applications; Blackie Academic & Professional: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Kleinhammes, A.; Wu, Y. NMR Study of Structure and Dynamics of Ionic Multiplets in Ethylene–Methacrylic Acid Ionomers. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 2781–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.L.; Dell, E.M. A Review of Shape Memory Polymers Bearing Reversible Binding Groups. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2016, 54, 1340–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchi, K.A.; Pantoja, M.; Cakmak, M. Shape Memory Ionomers. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2016, 54, 1389–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, K.; Eikerling, M.; Wang, Q.; Navessin, T.; Liu, Z. Self-Organization in Catalyst Layers of Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 13627–13634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagrodia, S.; Mohajer, Y.; Wilkes, G.; Storey, R.; Kennedy, J. New polyisobutylene-based model ionomers. Polym. Bull. 1983, 9, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.L.; Kurokawa, T.; Kuroda, S.; Ihsan, A.B.; Akasaki, T.; Sato, K.; Haque, M.A.; Nakajima, T.; Gong, J.P. Physical hydrogels composed of polyampholytes demonstrate high toughness and viscoelasticity. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Cao, Y.; Xue, B. Tough Hydrogels with Different Toughening Mechanisms and Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, R.K.; Hohlbein, N.; Garcia, S.J.; Schmidt, A.M.; Zwaag, S. Connecting supramolecular bond lifetime and network mobility for scratch healing in poly(butyl acrylate) ionomers containing sodium, zinc and cobalt. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 1697–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, P. Synthesis Methods, Chemical Structures and Phase Structures of Linear Polyurethanes. Properties and Applications of Linear Polyurethanes in Polyurethane Elastomers, Copolymers and Ionomers. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2007, 52, 915–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaudouin, O.; Robin, J.-J.; Lopez-Cuesta, J.-M.; Perrin, D.; Imbert, C. Ionomer-Based Polyurethanes: A Comparative Study of Properties and Applications. Polym. Int. 2012, 61, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, M.W.; Wetzel, M.D.; Troeltzsch, C.; Paul, D.R. Effects of Acid Neutralization on the Properties of K+ and Na+ Poly(ethylene-co-methacrylic acid) Ionomers. Polymer 2012, 53, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, B.P. Review and Critical Analysis of the Morphology of Random Ionomers Across Many Length Scales. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2008, 48, 1029–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, T.C.; Tobolsky, A.V. Viscoelastic Study of Ionomers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1967, 11, 2403–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capek, I. Dispersions of Polymer Ionomers: I. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 112, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, N.C.; Burghardt, W.R.; Winey, K.I. Blend Miscibility of Sulfonated Polystyrene Ionomers with Polystyrene: Effect of Counterion Valency and Neutralization Level. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 6401–6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, A.; Cohen, C.; Kim, H.; Winey, K.I.; Ando, N.; Gruner, S.M. Counterion Effect on the Rheology and Morphology of Tailored Poly(dimethylsiloxane) Ionomers. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 1630–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J.M.; Li, G.; Ocon, J.; Chuang, P.-Y.A. Unraveling Alkaline Oxygen Evolution Reaction: From Ionomer Binder Materials to Electrode Engineering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 48160–48172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanoja, G.E.; Schauser, N.S.; Bartels, J.M.; Evans, C.M.; Helgeson, M.E.; Seshadri, R.; Segalman, R.A. Ion Transport in Dynamic Polymer Networks Based on Metal–Ligand Coordination: Effect of Cross-Linker Concentration. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 2017–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, N.; Kim, J.; Cavicchi, K.A.; Khabaz, F. Microscopic Morphology and Dynamics of Polyampholyte and Cationic Ionomers. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 3937–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutemar, E.P.; Jannasch, P. Locating Sulfonic Acid Groups on Various Side Chains to Poly(arylene ether sulfone)s: Effects on the Ionic Clustering and Properties of Proton-Exchange Membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 351, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, O.S.; Babkin, A.V.; Ivanchenko, A.V.; Shachneva, S.S.; Nechausov, S.S.; Alentiev, D.A.; Bermeshev, M.V.; Bulgakov, B.A.; Kepman, A.V. Ionomers Based on Addition and Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerized 5-phenyl-2-norbornene as a Membrane Material for Ionic Actuators. Membranes 2022, 12, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, O.S.; Bulgakov, B.A.; Ivanchenko, A.V.; Shachneva, S.S.; Nechausov, S.S.; Bermeshev, M.V.; Kepman, A.V. Data on synthesis and characterization of sulfonated poly(phenylnorbornene) and polymer electrolyte membranes based on it. Data Brief 2019, 27, 104626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Silva, M.; Clarke, C.; Lynn, B.; Robertson, M.; Leopold, A.J.; Agede, O.; He, L.; Creager, S.; Roberts, M.E.; et al. Superior Proton Conductivity and Selectivity in Sulfonated Ionomer Biocomposites Containing Renewably Processed and Fractionated Lignin. RSC Sustain. 2025, 3, 2333–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, G.; Gao, H.; Guo, T.; Wu, L.; Zhou, X.; Cai, D.; Geng, K.; Li, N. The Effect of Ion Exchange Capacity Values of Sulfonated Poly(oxindole biphenylene) Ionomer in Cathode for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. J. Power Sources 2025, 631, 236246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Feng, Q.; Xie, L.; Zhang, D. About the Choice of Protogenic Group for Polymer Electrolyte Membranes: Alkyl or Aryl Phosphonic Acid? Solid State Ion. 2011, 190, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idupulapati, N.; Devanathan, R.; Dupuis, M. Atomistic Simulations of Perfluorophosphonic and Phosphinic Acid Membranes and Comparisons to Nafion. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 2959–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqman, M.; Kim, J.S. Effects of the Cation Valence on the Mechanical Properties of Sulfonated Polystyrene Ionomers Containing Dicarboxylate Salts. Polym. Bull. 2012, 69, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oza, Y.V.; MacFarlane, D.R.; Forsyth, M.; O’Dell, L.A. Characterisation of Ion Transport in Sulfonate Based Ionomer Systems Containing Lithium and Quaternary Ammonium Cations. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 175, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.R.; Murdakes, N.; Cornelius, C.J. Tuning Quaternary Ammonium Ionomer Composition and Processing to Produce Tough Films. Polymer 2018, 142, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Cai, Z.; Yang, L.; Lu, H. Salt- and pH-Triggered Helix–Coil Transition of Ionic Polypeptides under Physiological Conditions. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 2089–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T.; Noda, N.; Fujimoto, C.; Ito, M.; Takeuchi, H.; Nishiwaki, M.; Mori, Y. Ion-Pair Extraction of Quaternary Ammoniums Using Tetracyanocyclopentadienides and Synthetic Application for Complex Ammoniums. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 3081–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maegawa, K.; Wlazło, M.; Phuc, N.H.H.; Hikima, K.; Kawamura, G.; Nagai, A.; Matsuda, A. Synthesis and Structure–Electrochemical Property Relationships of Hybrid Imidazole-Based Proton Conductors for Medium-Temperature Anhydrous Fuel Cells. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 7708–7718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Qiu, L.; Qiu, B.; Peng, Y.; Yan, F. A Soluble and Conductive Polyfluorene Ionomer with Pendant Imidazolium Groups for Alkaline Fuel Cell Applications. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 9642–9649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Hickner, M.A. Ion Clustering in Quaternary Ammonium Functionalized Benzylmethyl Containing Poly(arylene ether ketone)s. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 9270–9278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Huang, J.; Chen, F.; Ye, D.; Song, J.; Xu, G.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q. Imidazole-Tailored Ionomers Achieve Concurrent Proton Conduction Boost and Electron Transport Retention in the Anode Catalyst Layer for PEM Water Electrolysis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 14693–14701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Wu, Z.; Li, X.; Guo, X.; Xu, J. Inhibition of Asphaltene Precipitation by Ionic Liquid Polymers Containing Imidazole Pendants and Alkyl Branches. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 6831–6842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alice Ng, C.-W.; MacKnight, W.J. Ionomeric Blends of Poly(ethylacrylate-co-4-vinylpyridine) with Zinc-Neutralized Sulfonated Poly(ethylene terephthalate). 1. Effect of Specific Interactions upon the Amorphous Phase. Macromolecules 1994, 27, 3027–3032. [Google Scholar]

- Alice Ng, C.-W.; MacKnight, W.J. Ionomeric Blends of Poly(ethyl acrylate-co-4-vinylpyridine) with Zinc-Neutralized Sulfonated Poly(ethylene terephthalate). Effect of Specific Interactions upon the Crystalline Phase. Macromolecules 1994, 27, 3033–3038. [Google Scholar]

- Alice Ng, C.-W.; MacKnight, W.J. Ionomeric Blends of Poly(ethyl acrylate-co-4-vinylpyridine) with Metal-Neutralized Sulfonated Poly(ethylene terephthalate). Effects of Counterions. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 2421–2429. [Google Scholar]

- Alice Ng, C.-W.; MacKnight, W.J. Ionomeric Blends of Poly(ethyl acrylate-co-4-vinylpyridine) with Zinc-Neutralized Sulfonated Poly(ethylene terephthalate). Effects of Functionalization Level. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 2412–2420. [Google Scholar]

- Pekkanen, A.M.; Zawaski, C.; Stevenson, A.T., Jr.; Dickerman, R.; Whittington, A.R.; Williams, C.B.; Long, T.E. Poly(ether ester) Ionomers as Water-Soluble Polymers for Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing Processes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 12324–12331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Ye, Z.; Berry, R. Modification of Cellulose Nanocrystals with Quaternary Ammonium-Containing Hyperbranched Polyethylene Ionomers by Ionic Assembly. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 4937–4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkholtz, H.M.; Chong, L.; Kaiser, Z.B.; Xu, T.; Liu, D.-J. Highly Active Non-PGM Catalysts Prepared from Metal Organic Frameworks. Catalysts 2015, 5, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, D.; Negi, Y.S.; Kumar, V. Modification of Poly(ether ether ketone) Polymer for Fuel Cell Application. J. Appl. Chem. 2013, 2013, 845602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Thabit, N.Y.; Ali, S.A.; Zaidi, S.J.; Mezghani, K. Novel Sulfonated Poly(ether ether ketone)/Phosphonated Polysulfone Polymer Blends for Proton Conducting Membranes. J. Mater. Res. 2012, 27, 1958–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rager, T.; Schuster, M.; Steininger, H.; Kreuer, K.D. Poly(1,3-phenylene-5-phosphonic acid), a Fully Aromatic Polyelectrolyte with High Ion Exchange Capacity. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 3317–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potaufeux, J.-E.; Odent, J.; Notta-Cuvier, D.; Delille, R.; Barrau, S.; Giannelis, E.P.; Lauro, F.; Raquez, J.-M. Mechanistic insights on ultra-tough polylactide-based ionic nanocomposites. Sci. Technol. 2020, 191, 108075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.-Y.; Zhao, X.; Illeperuma, W.R.K.; Chaudhuri, O.; Oh, K.H.; Mooney, D.J.; Vlassak, J.J.; Suo, Z. Highly stretchable and tough hydrogels. Nature 2012, 489, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Ren, X.; Gao, G. The Role of Chemical and Physical Crosslinking in Different Deformation Stages of Hybrid Hydrogels. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 100, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschanel, S.; Greviskes, B.P.; Bertoldi, K.; Sarva, S.S.; Chen, W.; Samuels, S.L.; Cohen, R.E.; Boyce, M.C. Rate dependent finite deformation stress–strain behavior of an ethylene methacrylic acid copolymer and an ethylene methacrylic acid butyl acrylate copolymer. Polymer 2009, 50, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lu, S.; Zhang, W. A crown-ether-based polyurethane with enhanced energy dissipation via sacrificing host-guest complex structures. Polymer 2025, 333, 128681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Liao, Y.; Tan, S.; Wang, C.; Wu, Y. Supramolecular Poly(Ionic Liquid)-Based Humidity and Deformation-Insensitive Sensor for Ultrasensitive Temperature Sensing. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 12594–12603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickner, M.A.; Ghassemi, H.; Kim, Y.S.; Einsla, B.R.; McGrath, J.E. Alternative Polymer Systems for Proton Exchange Membranes (PEMs). Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4587–4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odent, J.; Wallin, T.J.; Pan, W.; Kruemplestaedter, K.; Shepherd, R.F.; Giannelis, E.P. Highly Elastic, Transparent, and Conductive 3D-Printed Ionic Composite Hydrogels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1701807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, L. Ultrastretchable and Self-Healing Double-Network Hydrogel for 3D Printing and Strain Sensor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 26429–26437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Zhao, Q.; Evans, C.M. Precise Network Polymerized Ionic Liquids for Low-Voltage, Dopant-Free Soft Actuators. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2019, 4, 1800535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, S.S.; Schalenbach, M.; Schestakow, M.; Eichel, R.-A. The Effect of Ionomer Molecular Weight on Gravimetric Water Uptake, Hydrogen Permeability, Ionic Conductivity and Degradation Behavior of Anion Exchange Membranes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 151, 150126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, Y.P.; Orfino, F.P.; Kjeang, E. X-ray Computed Tomography Visualization of Liquid Water in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells: A State-of-the-Art Review. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 12997–13019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, X.-M.; Liu, J.-J.; Jia, J.; Ibragimov, A.B.; Gao, J. Phospholipid-Bioinspired Hydrogen-Bonded Organic Frameworks for Ultrahigh Proton Conductivity. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 14133–14139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, R.; Bora, M.M.; Upadhyaya, M.; Kakati, D.K. Conductive Composites from Polyaniline and Polyurethane Sulphonate Anionomer. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132, 41600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, C.E.; Pérez, R.L.; Mathaga, J.K.; Watson, A.; Evans, T.; Warner, I.M. Fluorescent Ionic Probe for Determination of Mechanical Properties of Healed Poly(ethylene-co-methacrylic acid) Ionomer Films. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricks-Laskoski, H.L.; Snow, A.W. Synthesis and Electric Field Actuation of an Ionic Liquid Polymer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 12402–12403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, C.; Pugal, D.; Oh, I.K.; Kim, K.J.; Asaka, K. Recent Advances in Ionic Polymer-Metal Composite Actuators and Their Modeling and Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013, 38, 1037–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, R.B.d.; Agrawal, P.; Brito, G.d.F.; Mélo, T.J.A.d. Exploring Shape Memory and Self-Healing Behavior in Sodium and Zinc Neutralized Ethylene/Methacrylic Acid (EMAA) Ionomers. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 7304–7317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Brostowitz, N.R.; Cavicchi, K.A.; Weiss, R.A. Perspective: Ionomer Research and Applications. Macromol. React. Eng. 2014, 8, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Villajos, R.; Sánchez, M.; Leones, A.; Peponi, L.; Manzano-Santamaría, J.; López, A.J.; Ureña, A. An Analysis of the Self-Healing and Mechanical Properties as well as Shape Memory of 3D-Printed Surlyn® Nanocomposites Reinforced with Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes. Polymers 2023, 15, 4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Xiao, J.; Xia, L. Intelligent Eucommia ulmoides Rubber/Ionomer Blends with Thermally Activated Shape Memory and Self-Healing Properties. Polymers 2023, 15, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raidt, T.; Hoeher, R.; Meuris, M.; Katzenberg, F.; Tiller, J.C. Ionically Cross-Linked Shape Memory Polypropylene. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 6918–6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Weiss, R.A. Sulfonated Poly(ether ether ketone) Ionomers and Their High Temperature Shape Memory Behavior. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 1732–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Wang, M.; Xia, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Jia, X.; Cao, R.; Wang, X. Self-Healing, Thermadapt Triple-Shape Memory Ionomer Vitrimer for Shape Memory Triboelectric Nanogenerator. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 50101–50111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolog, R.; Weiss, R.A. Shape Memory Behavior of a Polyethylene-Based Carboxylate Ionomer. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 7845–7852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Correas, T.; Shirole, A.; Crippa, F.; Fink, A.; Weder, C.; Corcuera, M.A.; Eceiza, A. Biocompatible Thermo- and Magneto-Responsive Shape-Memory Polyurethane Bionanocomposites. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 97, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behera, P.K.; Mondal, P.; Singha, N.K. Polyurethane with an Ionic Liquid Crosslinker: A New Class of Super Shape Memory-like Polymers. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 4205–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, L.W.; Zhang, F.H.; Leng, J.; Liu, Y. Shape Memory Polymers and Their Composites in Biomedical Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 97, 864–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Huete, N.; Post, W.; Laza, J.M.; Vilas, J.L.; León, L.M.; García, S.J. Effect of the Blend Ratio on the Shape Memory and Self-Healing Behaviour of Ionomer-Polycyclooctene Crosslinked Polymer Blends. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 98, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Choufi, N.; Mustapha, S.; Tehrani-Bagha, A.R.; Grady, B.P. Self-Healability of Poly(Ethylene-co-Methacrylic Acid): Effect of Ionic Content and Neutralization. Polymers 2022, 14, 3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirabedini, S.M.; Alizadegan, F. Ionomers as Self-Healing Materials. In Self-Healing Polymer-Based Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 279–291. [Google Scholar]

- Tita, S.P.S.; Magalhães, F.D.; Paiva, D.; Bertochi, M.A.Z.; Teixeira, G.F.; Pires, A.L.; Pereira, A.M.; Tarpani, J.R. Flexible Composite Films Made of EMAA−Na+ Ionomer: Evaluation of the Influence of Piezoelectric Particles on the Thermal and Mechanical Properties. Polymers 2022, 14, 2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Xiong, H.; Wu, Q.; Gu, S.; Liu, X.; Huang, G.; Wu, J. Electron-Donating Effect Enabled Simultaneous Improvement on the Mechanical and Self-Healing Properties of Bromobutyl Rubber Ionomers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 53239–53246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Liu, D.; Shi, L.-Y.; Tang, L.; Yang, K.-K.; Wang, Y.-Z. Fabricating Remote-Controllable Dynamic Ionomer/CNT Networks via Cation–π Interaction for Multi-Responsive Shape Memory and Self-Healing Capacities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 17424–17432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, S.; Sun, F. Photocured Materials with Self-Healing Function through Ionic Interactions for Flexible Electronics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 26694–26704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, Y.; Qin, R.; Xu, M.; Sheng, Y.; Lu, X. Robust Poly(urethane-amide) Protective Film with Fast Self-Healing at Room Temperature. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vislavath, P.; Billa, S.; Praveen, S.; Bahadur, J.; Sudarshan, K.; Patro, T.U.; Rath, S.K.; Ratna, D. Heterogeneous Coordination Environment and Unusual Self-Assembly of Ionic Aggregates in a Model Ionomeric Elastomer: Effect of Curative Systems. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 6739–6749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Pan, Y.; Yang, M.; Fernandez, C.; Chen, X.; Peng, Q. A Lactoglobulin-Composite Self-Healing Coating for Mg Alloys. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 6843–6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sistani, S.; Shekarchizadeh, H. Recent Trends and Advances in Biopolymer-Based Self-Healing Materials for Smart Food Packaging: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 312, 144130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, J.; Wang, T.; Sun, W.; Tong, Z. Polyampholyte Hydrogels with pH Modulated Shape Memory and Spontaneous Actuation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1707245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Mi, L.; Han, X.; Bai, T.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Jiang, S. Differences in Cationic and Anionic Charge Densities Dictate Zwitterionic Associations and Stimuli Responses. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 6956–6962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, W.; Bose, R.K.; García, S.J.; Van der Zwaag, S. Healing of Early Stage Fatigue Damage in Ionomer/Fe3O4 Nanoparticle Composites. Polymers 2016, 8, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Qiu, S.; Song, L. Ethanol Inducing Self-Assembly of Poly-(thioctic acid)/graphene Supramolecular Ionomers for Healable, Flame-Retardant, Shape-Memory Electronic Devices. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 629, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, V.M.S.; Srivastava, S. Time-Ionic Strength Superposition: A Unified Description of Chain Relaxation Dynamics in Polyelectrolyte Complexes. ACS Macro Lett. 2020, 9, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.; Mayumi, K.; Creton, C.; Narita, T.; Hui, C.-Y. Time Dependent Behavior of a Dual Cross-Link Self-Healing Gel: Theory and Experiments. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 7243–7250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Wu, Q.; Xiong, H.; Huang, G.; Wu, J. Reinforcing Self-Healing and Re-processable Ionomers with Carbon Black: An Investigation on the Network Structure and Molecular Mobility. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 216, 109035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geise, G.M.; Freeman, B.D.; Paul, D.R. Characterization of a Sulfonated Pentablock Copolymer for Desalination Applications. Polymer 2010, 51, 5815–5822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsumizu, S.; Nagao, N.; Tadano, K.; Tachino, H.; Hirasawa, E.; Yano, S. Effects of water sorption on the structure and properties of ethylene ionomers. Macromolecules 1992, 25, 6829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazuin, C.G.; Eisenberg, A. Ion containing polymers: Ionomers. J. Chem. Educ. 1981, 58, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickner, M.A.; Herring, A.M.; Coughlin, E.B. Anion Exchange Membranes: Current Status and Moving Forward. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2013, 51, 1727–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Young, N.P.; Grant, P.S. Spray Processing of TiO2 Nanoparticle/Ionomer Coatings on Carbon Nanotube Scaffolds for Solid-State Supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 11022–11028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morselli, D.; Cataldi, P.; Paul, U.C.; Ceseracciu, L.; Benitez, J.J.; Scarpellini, A.; Guzman-Puyol, S.; Heredia, A.; Valentini, P.; Pompa, P.P.; et al. Zinc Polyaleuritate Ionomer Coatings as a Sustainable, Alternative Technology for Bisphenol A-Free Metal Packaging. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 15484–15495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, K.-J.; Lee, S.-P.; Kong, D.-C.; Chen, F.L. Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Poly(trimethylene terephthalate) (PTT)/Cationic Dyeable Poly(trimethylene terephthalate) (CD-PTT) Polyblended Fibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 102, 1008–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Auria, S.; Neuteboom, P.; Pinalli, R.; Dalcanale, E.; Vachon, J. Polyethylene Ionomers as Thermally Reversible and Aging Resilient Adhesives. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 211, 113000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumasari, C.; Meidyawati, R.; Aprillia, I.; Arrizza, A.M.; Hillary, N.; Abdou, A. Synergistic Effect of Enzymatic Deproteinization and Surface Pre-Reacted Glass Ionomer “SPRG” Fillers in Self-Etch Adhesives: Boosting Anti-Demineralization and ABRZ. J. Dent. 2025, 162, 106088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Gao, D.; Lin, G.; Sun, W. Static and Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Epoxy Nanocomposites Reinforced by Hybridization with Carbon Nanofibers and Block Ionomers. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2022, 271, 108638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, X. Engineering Stable Proton Exchange Membrane via Hybridization of Nonsulfonated Poly(ether sulfone) with Sulfonated Amide Organic Frameworks. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 10283–10292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, I.; Saccà, A.; Sebastián, D.; Baglio, V.; Aricò, A.S.; Oldani, C.; Merlo, L.; Carbone, A. Influence of Ionomer Content in the Catalytic Layer of MEAs Based on Aquivion® Ionomer. Polymers 2021, 13, 3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

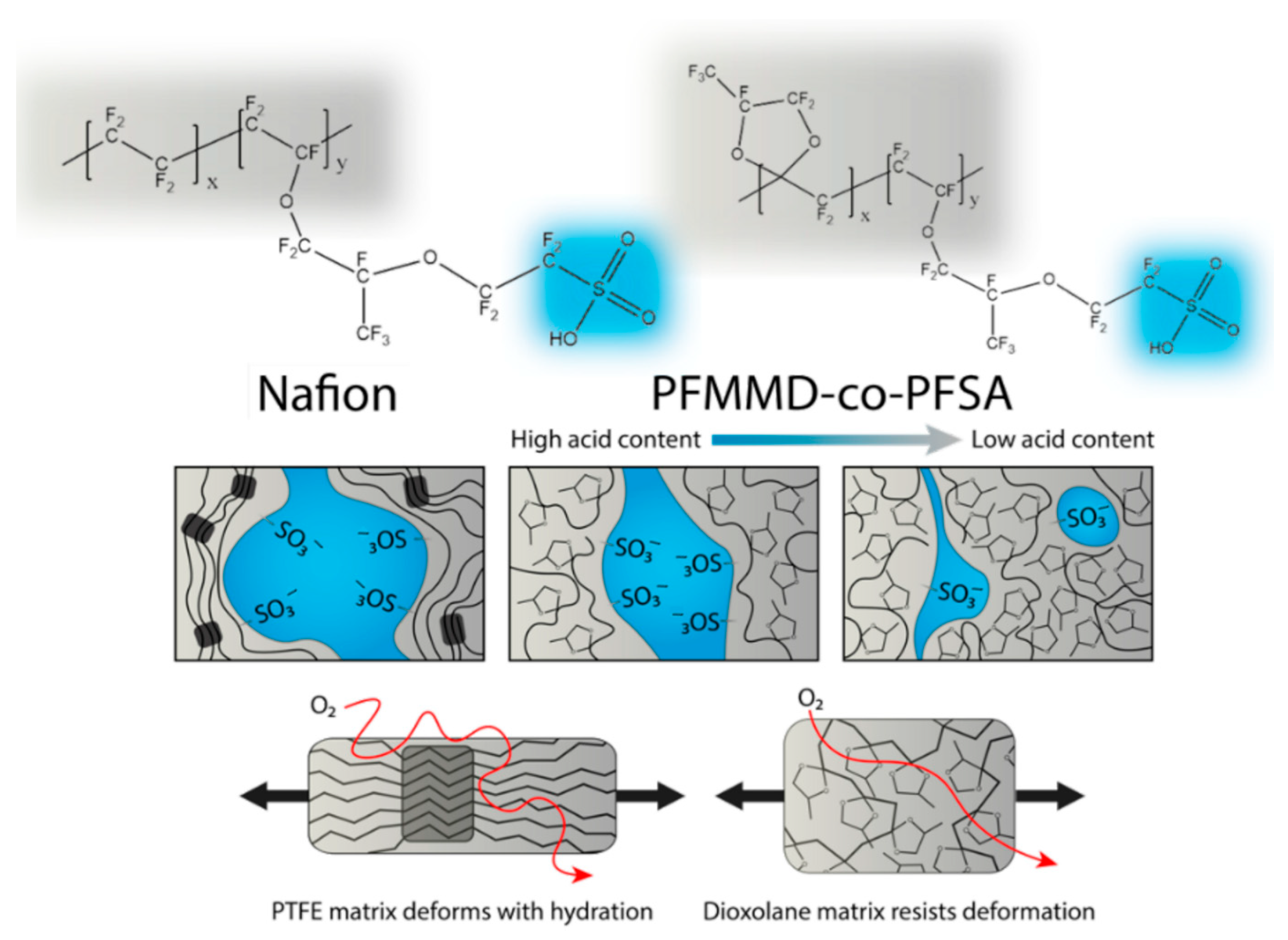

- Mauritz, K.A.; Moore, R.B. State of Understanding of Nafion. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4535–4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

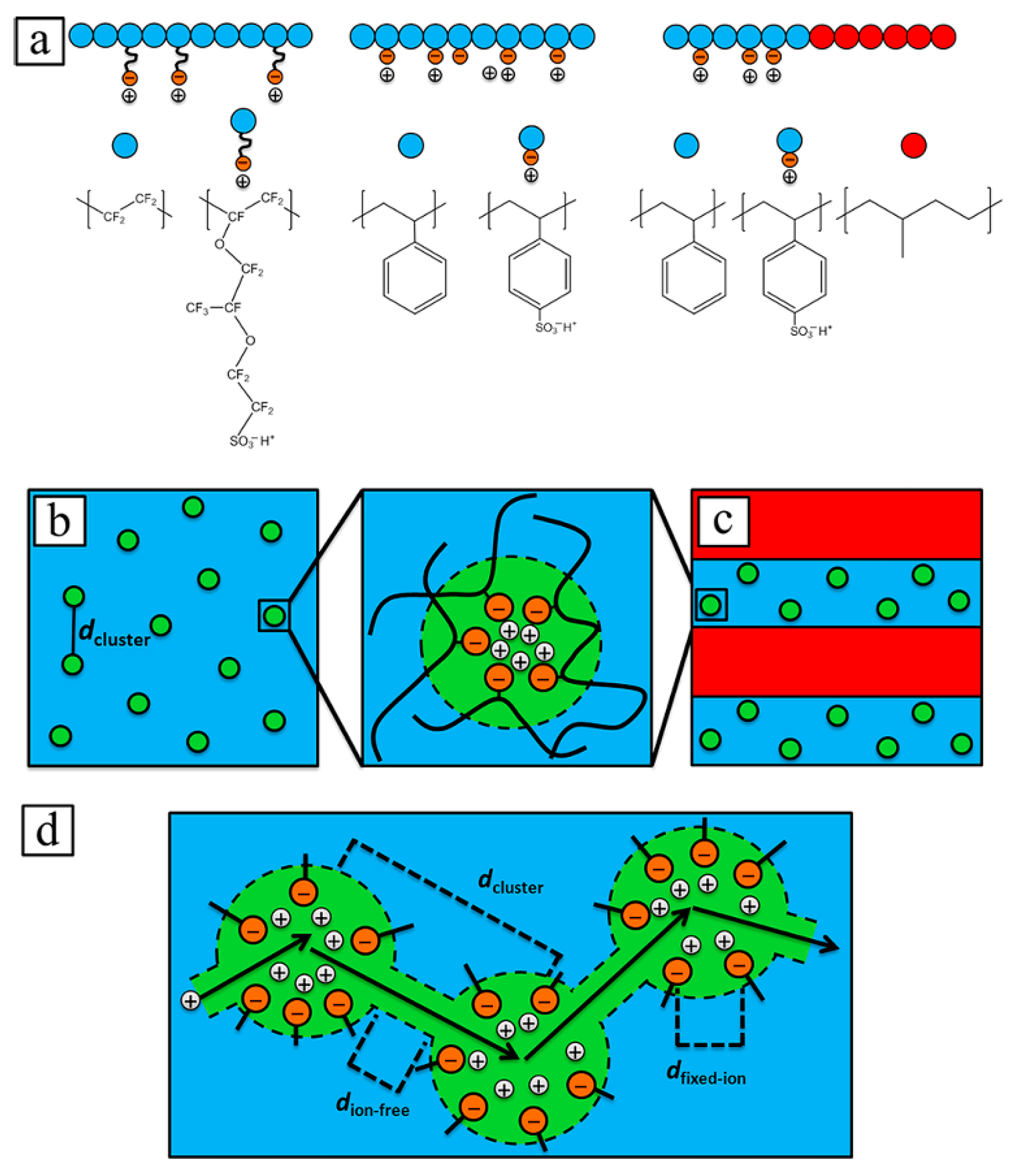

- Kreuer, K.D.; Portale, G. A Critical Revision of the Nano Morphology of Proton Conducting Ionomers and Polyelectrolytes for Fuel Cell Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 5390–5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollet, A.L.; Diat, O.; Gebel, G. A New Insight into Nafion Structure. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 106, 3033–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grot, W. Discovery and Development of Nafion Perfluorinated Membranes. Chem. Ind. 1985, 18, 647–649. [Google Scholar]

- Gebel, G.; Lambard, J. Small-Angle Scattering Study of Water Swollen Perfluorinated Ionomer Membranes. Macromolecules 1997, 30, 7914–7920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.I.; Comolli, L.R.; Kusoglu, A.; Modestino, M.A.; Minor, A.M.; Weber, A.Z. Morphology of Hydrated As-Cast Nafion Revealed through Cryo Electron Tomography. ACS Macro Lett. 2015, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-H.; Yang, D.-S.; Yoon, S.J.; So, S.; Hong, S.-K.; Yu, D.M.; Hong, Y.T. TEMPO Radical-Embedded Perfluorinated Sulfonic Acid Ionomer Composites for Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 7631–7638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Q.; So, S.; Kim, H.-T.; Choi, S.Q. Highly Ordered Ultrathin Perfluorinated Sulfonic Acid Ionomer Membranes for Vanadium Redox Flow Battery. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Pan, P.; Bao, Y. Co-assembly of Perfluorinated Sulfonic-Acid Ionomer and Tetraphenylporphyrin Tetrasulfonic-Acid Contributes to High-Performance Proton-Exchange Membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 725, 124041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.H.; Hou, J.; Kim, W.Y.; Wi, S.; Lee, C.H. The Relationship Between Chemical Structure of Perfluorinated Sulfonic Acid Ionomers and Their Membrane Properties for PEMEC Application. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Nam, J.; Ahn, J.; Yoon, S.; Jeong, S.C.; Ju, H.; Lee, C.H. Perfluorinated Sulfonic Acid Ionomer Degradation After a Combined Chemical and Mechanical Accelerated Stress Test to Evaluate Membrane Durability for Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 96, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinami, S.; Hoshino, T.; Nakatani, T.; Miyajima, T.; Hikima, T.; Takata, M. Morphological Changes of Hydrophobic Matrix and Hydrophilic Ionomers in Water-Swollen Perfluorinated Sulfonic Acid Membranes Detected Using Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering. Polymer 2019, 180, 121699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.P.; Park, I.K.; Park, C.H.; Lee, C.H. Morphological Transformation of Perfluorinated Sulfonic Acid Ionomer via Ionic Complex Formation at a High Entropy State. Mater. Today Energy 2023, 33, 101250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierke, T.D.; Munn, G.E.; Wilson, F.C. The Morphology in Nafion Perfluorinated Membrane Products, as Determined by Wide- and Small-Angle X-Ray Studies. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 1981, 19, 1687–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Cui, J.; Yang, T.; Hu, C.; Zhong, Z.; Sun, Z.; Gong, Y.; Pei, S.; Zhang, Y. Intrinsic Emission and Tunable Phosphorescence of Perfluorosulfonate Ionomers with Evolved Ionic Clusters. Sci. China Chem. 2020, 63, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diat, O.; Gebel, G. Fuel Cells: Proton Channels. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusoglu, A.; Modestino, M.A.; Hexemer, A.; Segalman, R.A.; Weber, A.Z. Subsecond Morphological Changes in Nafion during Water Uptake Detected by Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering. ACS Macro Lett. 2012, 1, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuer, K.D. Ion Conducting Membranes for Fuel Cells and Other Electrochemical Devices. Chem. Mater. 2013, 26, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubatat, L.; Rollet, A.L.; Gebel, G.; Diat, O. Evidence of Elongated Polymeric Aggregates in Nafion. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 4050–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Rohr, K.; Chen, Q. Parallel Cylindrical Water Nanochannels in Nafion Fuel-Cell Membranes. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzenberg, A.; Mukherjee, D.; Dudenas, P.J.; Okamoto, Y.; Kusoglu, A.; Modestino, M.A. Dynamic Emergence of Nanostructure and Transport Properties in Perfluorinated Sulfonic Acid Ionomers. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 8519–8528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karan, K. Interesting Facets of Surface, Interfacial, and Bulk Characteristics of Perfluorinated Ionomer Films. Langmuir 2019, 35, 13489–13520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Guiver, M.D. Ion Transport by Nanochannels in Ion-Containing Aromatic Copolymers. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 2175–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, S.; Ruffmann, B.; Buder, I.; Nunes, S.P. Proton Conductive Membranes of Sulfonated Poly(ether ketone ketone). J. Membr. Sci. 2005, 260, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elabd, Y.A.; Hickner, M.A. Block Copolymers for Fuel Cells. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elabd, Y.A.; Napadensky, E.; Walker, C.W.; Winey, K.I. Transport Properties of Sulfonated Poly(styrene-b-isobutylene-b-styrene) Triblock Copolymers at High Ion-Exchange Capacities. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Zhang, M.; Yuan, X.; Lvov, S.N.; Chung, T.C.M. Synthesis of Polyethylene-Based Proton Exchange Membranes Containing PE Backbone and Sulfonated Poly(arylene ether sulfone) Side Chains for Fuel Cell Applications. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 2460–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakabayashi, K.; Higashihara, T.; Ueda, M. Polymer Electrolyte Membranes Based on Cross-Linked Highly Sulfonated Multiblock Copoly(ether sulfone)s. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 5756–5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

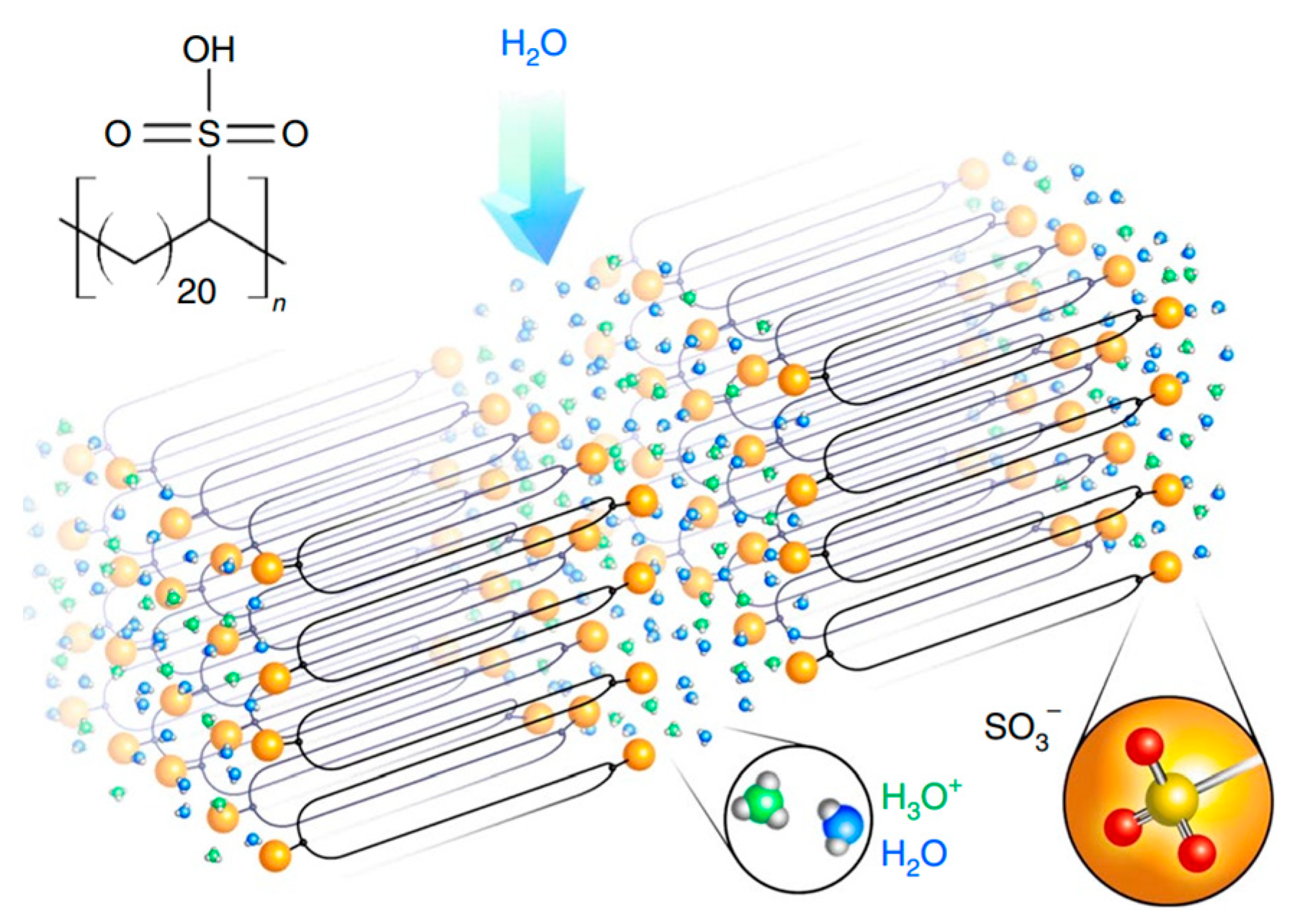

- Trigg, E.B.; Middleton, L.R.; Moed, D.E.; Winey, K.I. Transverse Orientation of Acid Layers in the Crystallites of a Precise Polymer. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 8988–8995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, J.; Krishna Prasad, S.; Rao, D.S.S.; Ramakrishnan, S. Periodically Clickable Polyesters: Study of Intrachain Self-Segregation Induced Folding, Crystallization, and Mesophase Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 2538–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigg, E.B.; Stevens, M.J.; Winey, K.I. Chain Folding Produces a Multilayered Morphology in a Precise Polymer: Simulations and Experiments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 3747–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines, T.W.; Bell, M.H.; Trigg, E.B.; Winey, K.I.; Wagener, K.B. Precision Sulfonic Acid Polyolefins via Heterogeneous to Homogeneous Deprotection. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2018, 219, 1700634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigg, E.B.; Gaines, T.W.; Maréchal, M.; Moed, D.E.; Rannou, P.; Wagener, K.B.; Stevens, M.J.; Winey, K.I. Self-Assembled Highly Ordered Acid Layers in Precisely Sulfonated Polyethylene Produce Efficient Proton Transport. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beers, K.M.; Balsara, N.P. Design of Cluster-Free Polymer Electrolyte Membranes and Implications on Proton Conductivity. ACS Macro Lett. 2012, 1, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarusso, D.J.; Cooper, S.L. Microstructure of Ionomers: Interpretation of Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering Data. Macromolecules 1983, 16, 1871–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.Y.; Gierke, T.D.J. Ion transport and clustering in nafion perfluorinated membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 1983, 13, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

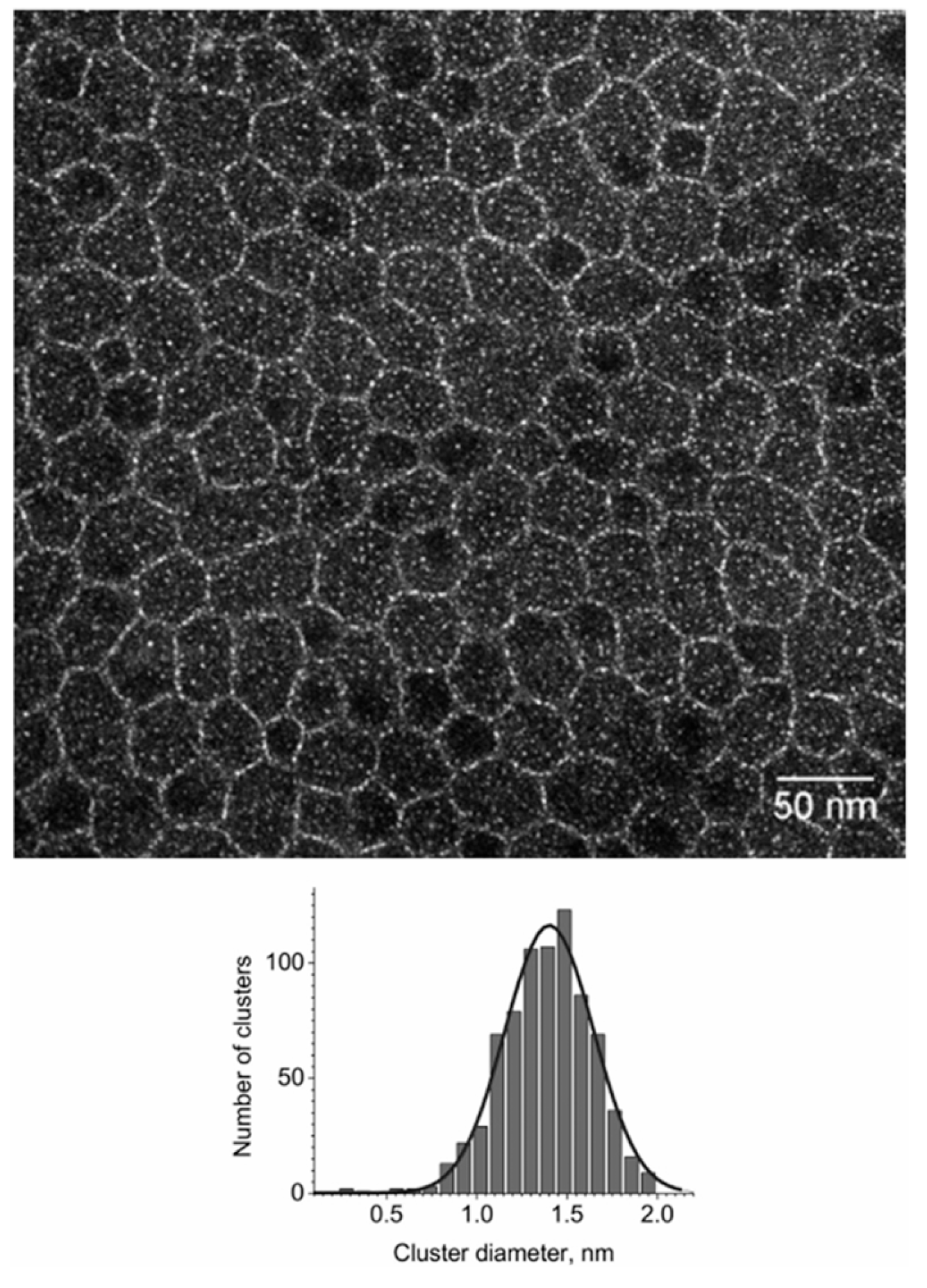

- Yakovlev, S.; Wang, X.; Ercius, P.; Balsara, N.P.; Downing, K.H. Direct Imaging of Nanoscale Acidic Clusters in a Polymer Electrolyte Membrane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 20700–20703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, W.H. Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 1998, 10, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, M.A. Polymer Electrolyte Reviews-1; MacCallum, J.R., Vincent, C.A., Eds.; Elsevier Applied Science: London, UK, 1987; pp. 173–236. [Google Scholar]

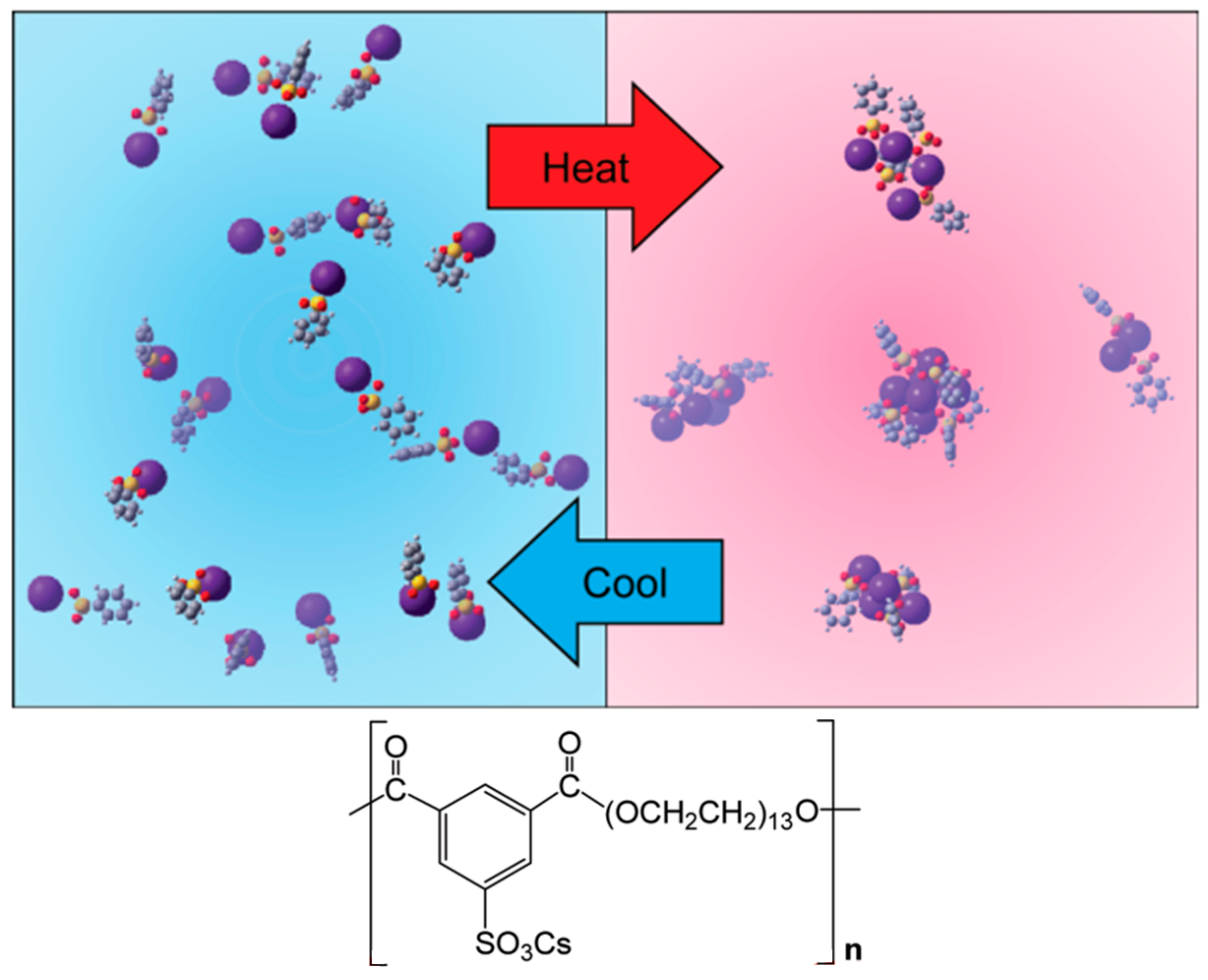

- Wang, W.; Tudryn, G.J.; Colby, R.H.; Winey, K.I. Thermally Driven Ionic Aggregation in Poly(ethylene oxide)-Based Sulfonate Ionomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 10826–10831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, C.F. Acyloxymetallosulfophthalate Containing Dyeable Polyesters. US Patent 3,185,671, 25 May 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm, G.J.; Roscoe, R.W. Sulfonate Containing Polyesters Dyeable with Basic Dyes. US Patent 3,018,272, 23 January 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.M.; Zhao, D.; Wang, L.Y.; Wu, Q.C. Synthesis and Characterization of Branched Poly(ethylene terephthalate). Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 738, 738–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greener, J.; Gillmor, J.; Daly, R. Melt Rheology of a Class of Polyester Ionomers. Macromolecules 1993, 26, 6416–6424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Z.; Chen, X.-T.; Tang, X.-D.; Du, X.-H. A New Approach for the Simultaneous Improvement of Fire Retardancy, Tensile Strength and Melt Dripping of Poly(ethylene terephthalate). J. Mater. Chem. 2003, 13, 1248–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Lin, Q.; Armentrout, R.S.; Long, T.E. Synthesis and Characterization of Telechelic Poly(ethylene terephthalate) Sodiosulfonate Ionomers. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 8738–8744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemeinhardt, G.C.; Moore, A.A.; Moore, R.B. Influence of Ionomeric Compatibilizers on the Morphology and Properties of Amorphous Polyester/Polyamide Blends. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2004, 44, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Prattipati, V.; Mehta, S.; Schiraldi, D.A.; Hiltner, A.; Baer, E. Improving Gas Barrier of PET by Blending with Aromatic Polyamides. Polymer 2005, 46, 2685–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.; Schiraldi, D.A. Role of Ionic Interactions in the Compatibility of Polyester Ionomers with Poly(ethylene terephthalate) and Nylon 6. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2006, 44, 2091–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özen, I.; Bozoklu, G.; Dalgıçdir, C.; Yücel, O.; Ünsal, E.; Çakmak, M.; Menceloğlu, Y.Z. Improvement in Gas Permeability of Biaxially Stretched PET Films Blended with High Barrier Polymers: The Role of Chemistry and Processing Conditions. Eur. Polym. J. 2010, 46, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prattipati, V.; Hu, Y.; Bandi, S.; Schiraldi, D.A.; Hiltner, A.; Baer, E.; Mehta, S. Effect of Compatibilization on the Oxygen-Barrier Properties of Poly(ethylene terephthalate)/Poly(m-xylylene adipamide) Blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 97, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.Y.; So, S.; Noh, Y.S.; Kim, J.; Jeong, H.Y.; Choi, J.; Yoon, S.J.; Yu, D.M.; Oh, K.-H. Hydrocarbon Ionomer/Polytetrafluoroethylene Composite Membranes Containing Radical Scavengers for Robust Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis. Eur. Polym. J. 2025, 234, 114024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Weiss, R.A. Nonlinear Rheology of Lightly Sulfonated Polystyrene Ionomers. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 2417–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

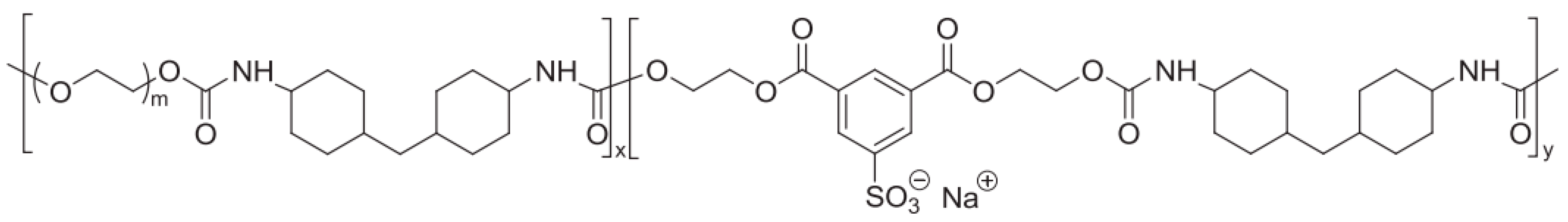

- Gao, R.; Zhang, M.; Dixit, N.; Moore, R.B.; Long, T.E. Influence of Ionic Charge Placement on Performance of Poly(ethylene glycol)-Based Sulfonated Polyurethanes. Polymer 2012, 53, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Hu, J. A Poly(ethylene glycol)-Based Smart Phase Change Material. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2008, 92, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.-M. Preparation and Characterization of PEG/MDI/PVA Copolymer as Solid–Solid Phase Change Heat Storage Material. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 113, 2041–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yu, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, M. Study on Phase-Change Characteristics of PET-PEG Copolymers. J. Macromol. Sci. Part B Phys. 2006, 45, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ding, E.; Li, G. Study on Transition Characteristics of PEG/CDA Solid-Solid Phase Change Materials. Polymer 2002, 43, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigo, T.L.; Bruno, J.S. Improvement of Various Properties of Fiber Surfaces Containing Crosslinked Polyethylene Glycols. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1989, 37, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, P.; Duan, Y.; Fei, P.; Xia, L.; Liu, R.; Cheng, B. Synthesis and Thermal Energy Storage Properties of the Polyurethane Solid–Solid Phase Change Materials with a Novel Tetrahydroxy Compound. Eur. Polym. J. 2012, 48, 1295–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Zheng, J.; Yang, H.; Guo, Y.; Li, W.; Li, X. Preparation and Characterization of Polyethylene Glycol/Active Carbon Composites as Shape-Stabilized Phase Change Materials. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2011, 95, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.-C.; Liu, P.-S. A Novel Solid–Solid Phase Change Heat Storage Material with Polyurethane Block Copolymer Structure. Energy Convers. Manag. 2006, 47, 3185–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

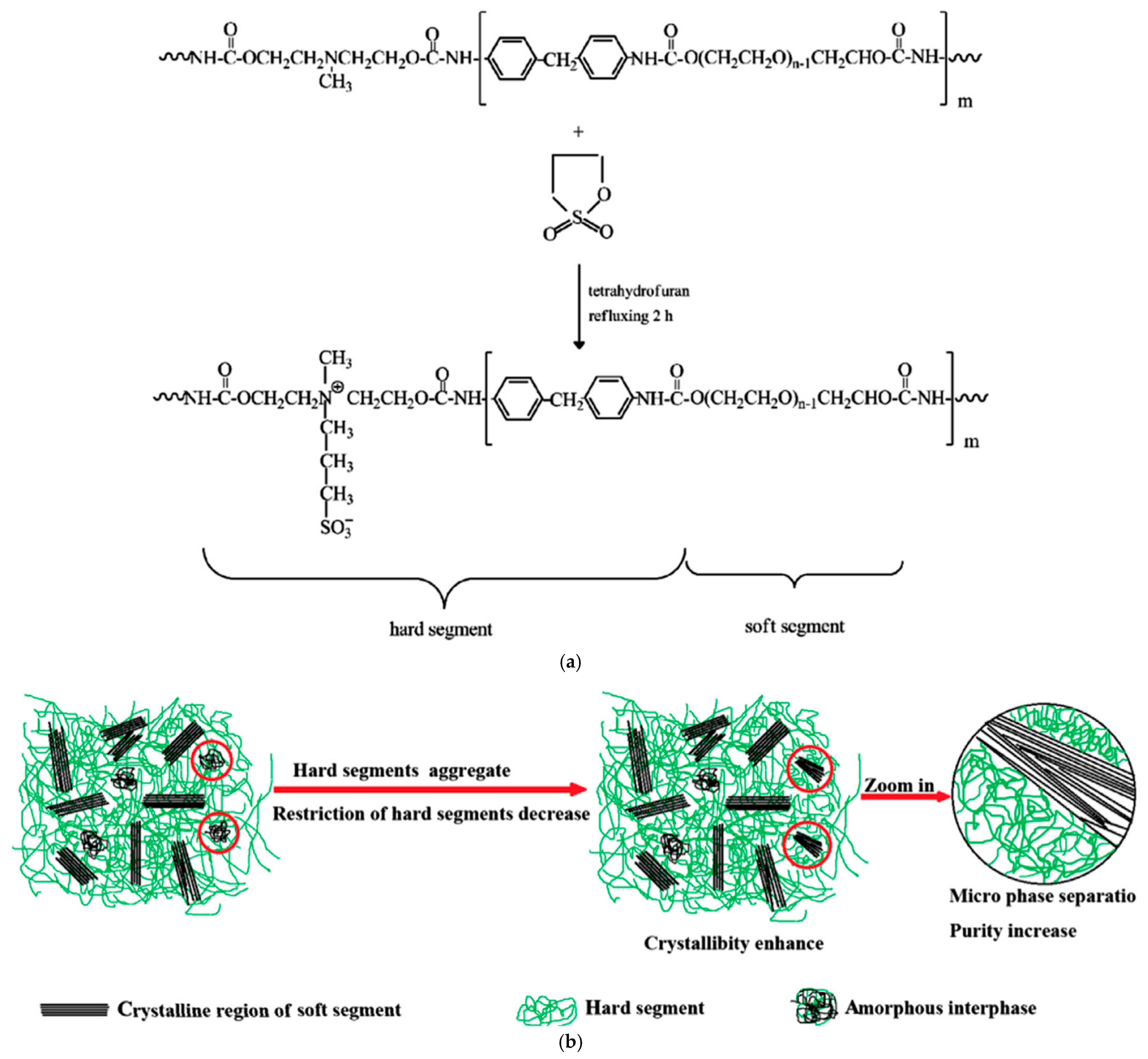

- Hwang, K.K.S.; Yang, C.-Z.; Cooper, S.L. Properties of Polyether-Polyurethane Zwitterionomers. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1981, 21, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davletbaeva, I.M.; Sazonov, O.O.; Mai, D.T.; Ibragimova, A.R. Copper Coordinated Segmented Polyurethanes and Their Electrophysical Properties. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e01334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davletbaeva, I.M.; Mai, D.T.; Sazonov, O.O.; Ibragimova, A.R.; Arkhipov, A.V.; Boltakova, N.V.; Davletbaev, R.S. Modification of Segmented Polyurethanes with Copper Coordination Compounds. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e05350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-Z.; Hwang, K.K.S.; Cooper, S.L. Morphology and Properties of Polybutadiene- and Polyether-Polyurethane Zwitterionomers. Makromol. Chem. 1983, 184, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hu, J.; Yeung, K.-w.; Choi, K.-f.; Liu, Y.; Liem, H. Effect of Cationic Group Content on Shape Memory Effect in Segmented Polyurethane Cationomer. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 103, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Liu, R.; Zou, C.; Shao, Q.; Lan, Y.; Cai, X.; Zhai, L. Linear Polyurethane Ionomers as Solid–Solid Phase Change Materials for Thermal Energy Storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2014, 130, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordo, F.; Mougnier, S.-J.; Loureiro, N.; Tournilhac, F.; Michaud, V. Design of Self-Healing Supramolecular Rubbers with a Tunable Number of Chemical Cross-Links. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 4394–4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Sallat, A.; Böhme, F.; Suckow, M.; Basu, D.; Wießner, S.; Stöckelhuber, K.W.; Voit, B.; Heinrich, G. Ionic Modification Turns Commercial Rubber into a Self-Healing Material. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 20623–20630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohlbein, N.; Shaaban, A.; Bras, A.R.; Pyckhout-Hintzen, W.; Schmidt, A.M. Self-Healing Dynamic Bond-Based Rubbers: Understanding the Mechanisms in Ionomeric Elastomer Model Systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 21005–21017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Wang, C.; Keplinger, C.; Zuo, J.L.; Jin, L.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, P.; Cao, Y.; Lissel, F.; Linder, C.; et al. A Highly Stretchable Autonomous Self-Healing Elastomer. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Ren, W.; Ang, E.H.; Song, L.; Zhu, J.; Hu, Y. Intrinsic Ionic Confinement Dynamic Engineering of Ionomers with Low Dielectric-k, High Healing and Stretchability for Electronic Device Reconfiguration. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 453, 139837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Cao, L.; Lin, B.; Liang, X.; Chen, Y. Design of Self-Healing Supramolecular Rubbers by Introducing Ionic Cross-Links into Natural Rubber via a Controlled Vulcanization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 17728–17737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Xie, Z.; Wen, J.; Bi, X.; Lv, P.; Dou, Y.; Wang, C.; Wu, J. Mechanically Robust and Recyclable Styrene–Butadiene Rubber Realized by Ion Cluster Dynamic Cross-Link. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 6025–6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, L.R.; Winey, K.I. Nanoscale Aggregation in Acid- and Ion-Containing Polymers. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2017, 8, 499–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwa, Y.; Kurachi, J.; Kohbara, Y.; Kutsumizu, S. Dynamic Ionic Crosslinks Enable High Strength and Ultrastretchability in a Single Elastomer. Commun. Chem. 2018, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippidi, E.; Cristiani, T.R.; Eisenbach, C.D.; Waite, J.H.; Israelachvili, J.N.; Ahn, B.K.; Valentine, M.T. Toughening Elastomers Using Mussel-Inspired Iron-Catechol Complexes. Science 2017, 358, 502–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwa, Y.; Taira, K.; Kurachi, J.; Udagawa, T.; Kutsumizu, S. A Gas-Plastic Elastomer That Quickly Self-Heals Damage with the Aid of CO2 Gas. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajita, T.; Noro, A.; Oda, R.; Hashimoto, S. Highly Impact-Resistant Block Polymer-Based Thermoplastic Elastomers with an Ionically Functionalized Rubber Phase. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 2821–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

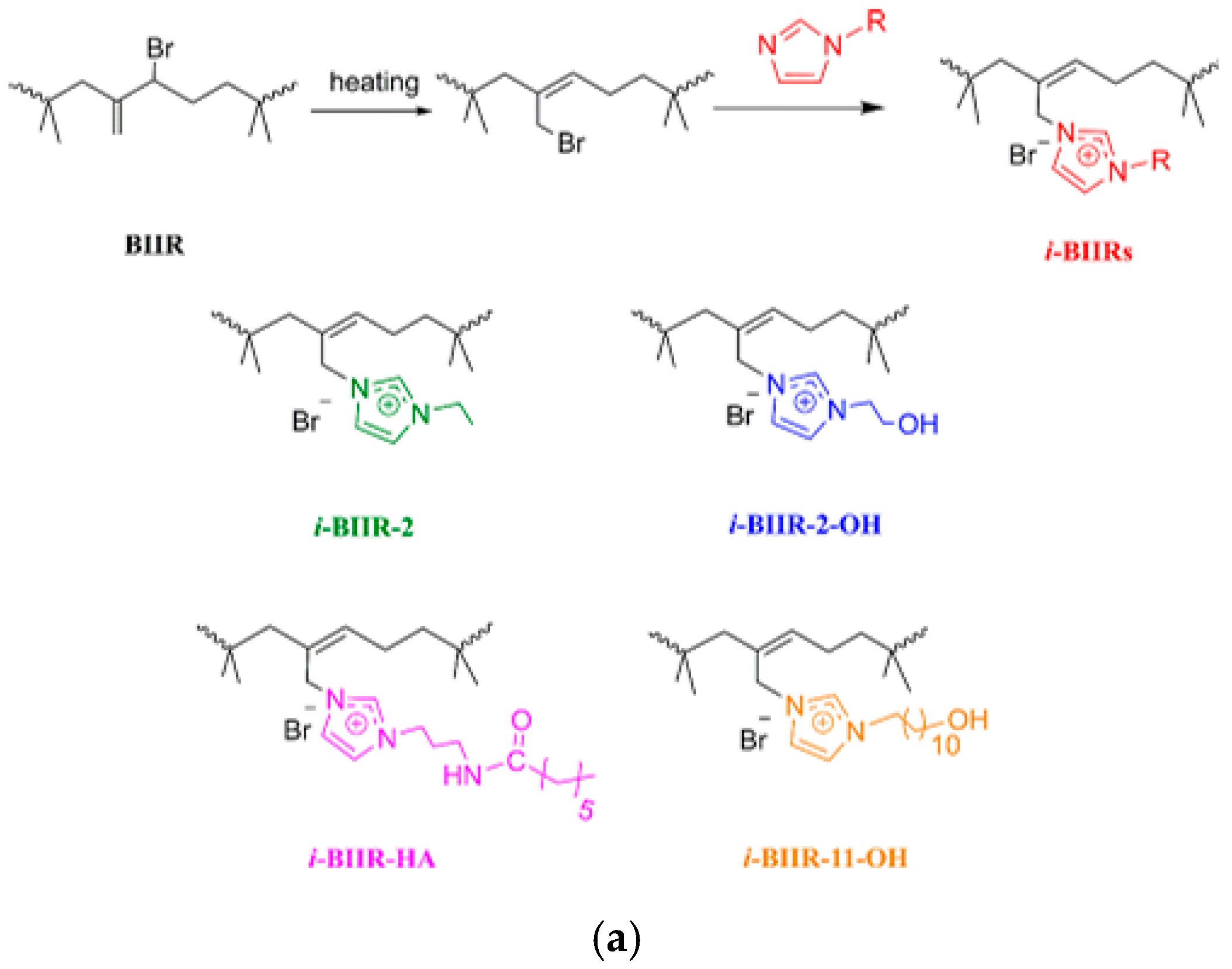

- Parent, J.S.; Porter, A.M.J.; Kleczek, M.R.; Whitney, R.A. Imidazolium Bromide Derivatives of Poly(isobutylene-co-isoprene): A New Class of Elastomeric Ionomers. Polymer 2011, 52, 5410–5418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, G.L.; Williams, C.K. Exploiting Sodium Coordination in Alternating Monomer Sequences to Toughen Degradable Block Polyester Thermoplastic Elastomers. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 2290–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Mao, X.; Ma, Z.; Pan, L.; Wang, B.; Li, Y. High-Performance Polyethylene-Ionomer-Based Thermoplastic Elastomers Exhibiting Counteranion-Mediated Mechanical Properties. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 4219–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, G.L.; Sulley, G.S.; Kimpel, J.; Łagodzińska, M.; Häfele, L.; Carrodeguas, L.P.; Williams, C.K. Block Poly(carbonate-ester) Ionomers as High-Performance and Recyclable Thermoplastic Elastomers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202210748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, J.; Dong, X.; Wang, D. Stretchable Self-Healing Plastic Polyurethane with Super-High Modulus by Local Phase-Lock Strategy. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2023, 44, 2200299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Yuan, X.; Wang, L.; Chung, T.C.M.; Huang, T.; deGroot, W. Synthesis and Characterization of Well-Controlled Isotactic Polypropylene Ionomers Containing Ammonium Ion Groups. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, L.R.; Trigg, E.B.; Yan, L.; Winey, K.I. Deformation-Induced Morphology Evolution of Precise Polyethylene Ionomers. Polymer 2018, 144, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Huang, C.; Weiss, R.A.; Colby, R.H. Viscoelasticity of Reversible Gelation for Ionomers. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, Q.; Weiss, R.A. Rheological Behavior of Partially Neutralized Oligomeric Sulfonated Polystyrene Ionomers. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Cao, X.; Huang, C.; Weiss, R.A.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Q. Brittle-to-Ductile Transition of Sulfonated Polystyrene Ionomers. ACS Macro Lett. 2021, 10, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Peng, L.; Huang, X.; Chen, Q. A Trade-Off Between Hardness and Stretchability of Associative Networks During the Sol-to-Gel Transition. J. Rheol. 2023, 67, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacy, E.W.; Gainaru, C.P.; Gobet, M.; Wojnarowska, Z.; Bocharova, V.; Greenbaum, S.G.; Sokolov, A.P. Fundamental Limitations of Ionic Conductivity in Polymerized Ionic Liquids. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 8637–8645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yekymov, E.; Attia, D.; Levi-Kalisman, Y.; Bitton, R.; Yerushalmi Rozen, R. Effects of Non-Ionic Micelles on the Acid-Base Equilibria of a Weak Polyelectrolyte. Polymers 2022, 14, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Du, H.; Wickramasinghe, S.R.; Qian, X. The Effects of Chemical Substitution and Polymerization on the pKa Values of Sulfonic Acids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 14094–14101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilmayer, R.; Kübelbeck, S.; Khalil, A.; Brodrecht, M.; Kunz, U.; Kleebe, H.-J.; Koller, H.; Hanna, J.V.; Dzubiella, J.; Andrieu-Brunsen, A. Influence of Nanoconfinement on the pKa of Polyelectrolyte Functionalized Silica Mesopores. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 7, 1901914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preguiça, E.; Kun, D.; Wacha, A.; Pukánszky, B. The Role of Ionic Clusters in the Determination of the Properties of Partially Neutralized Ethylene-Acrylic Acid Ionomers. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 142, 110110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balwani, A.; Davis, E.M. Anomalous, Multistage Liquid Water Diffusion and Ionomer Swelling Kinetics in Nafion and Nafion Nanocomposites. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Nakagawa, S.; Yoshie, N. Tunable Mechanical Properties in Microphase-Separated Thermoplastic Elastomers via Metal–Ligand Coordination. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 2351–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, D.; Yasuda, K.; Uchiyama, K.; Arimitsu, K. Tertiary Ammonium Counterions Outperform Quaternary Ammonium Counterions in Ionic Comb Polymers: Overcoming the Trade-Off Between Toughness and the Elastic Modulus. Polym. J. 2025, 57, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

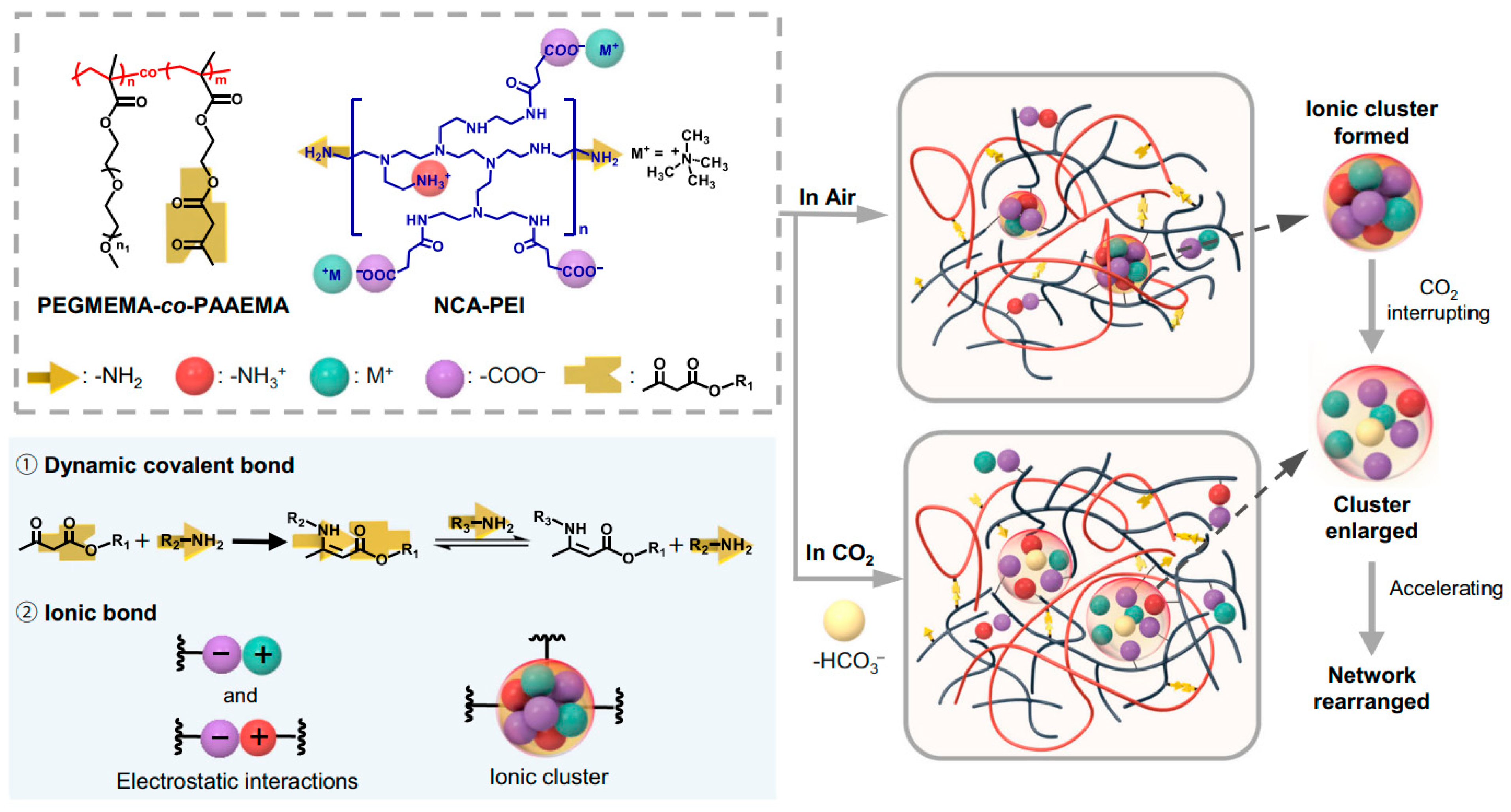

- Chen, J.; Li, L.; Luo, J.; Meng, L.; Zhao, X.; Song, S.; Demchuk, Z.; Li, P.; He, Y.; Sokolov, A.P.; et al. Covalent Adaptable Polymer Networks with CO2-Facilitated Recyclability. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, L.M.; Stevens, M.J.; Frischknecht, A.L. Dynamics of Model Ionomer Melts of Various Architectures. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 8097–8108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Kim, J.-S. Effects of Low Matrix Glass Transition Temperature on the Cluster Formation of Ionomers Having Two Ion Pairs per Ionic Repeat Unit. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 1870–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lendlein, A.; Kelch, S. Shape-Memory Polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2034–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Li, G. A Review of Stimuli-Responsive Shape Memory Polymer Composites. Polymer 2013, 54, 2199–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T. Recent Advances in Polymer Shape Memory. Polymer 2011, 52, 4985–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.A.; Izzo, E.; Mandelbaum, S. New Design of Shape Memory Polymers: Mixtures of an Elastomeric Ionomer and Low Molar Mass Fatty Acids and Their Salts. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 2978–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

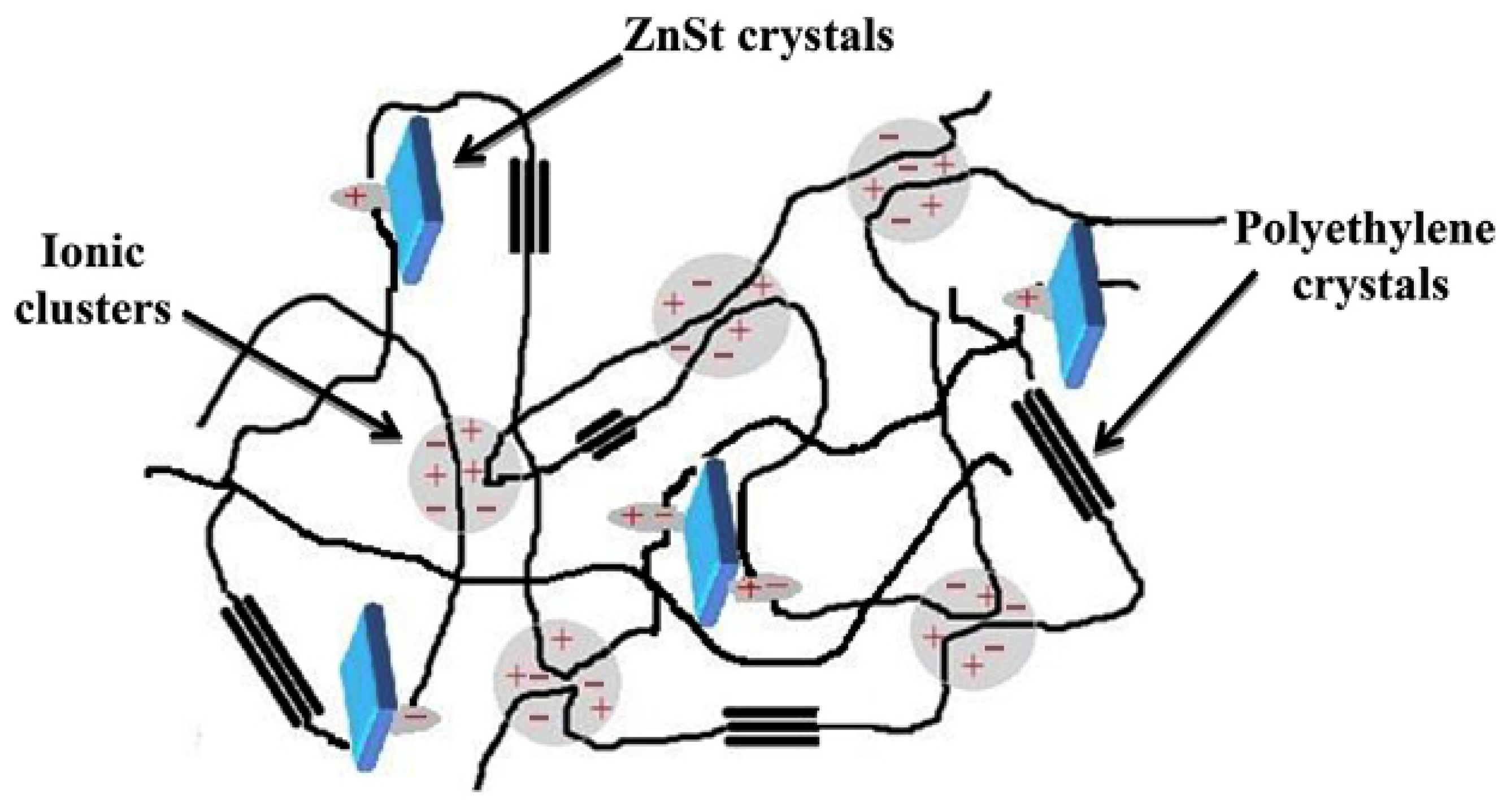

- Dong, J.; Weiss, R.A. Effect of Crosslinking on Shape-Memory Behavior of Zinc Stearate/Ionomer Compounds. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2013, 214, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yoonessi, M.; Weiss, R.A. High Temperature Shape Memory Polymers. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 4160–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Yue, Z.; Qian, H.; Li, W.; Xu, J.; Yang, H. Water-Alcohol Dispersible and Self-Cross-Linkable Sulfonated Poly(ether ether ketone): Application as Ionomer for Direct Methanol Fuel Cell Catalyst Layer. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 6958–6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolog, R.; Weiss, R.A. Properties and Shape-Memory Behavior of Compounds of a Poly(ethylene-co-methacrylic acid) Ionomer and Zinc Stearate. Polymer 2017, 128, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

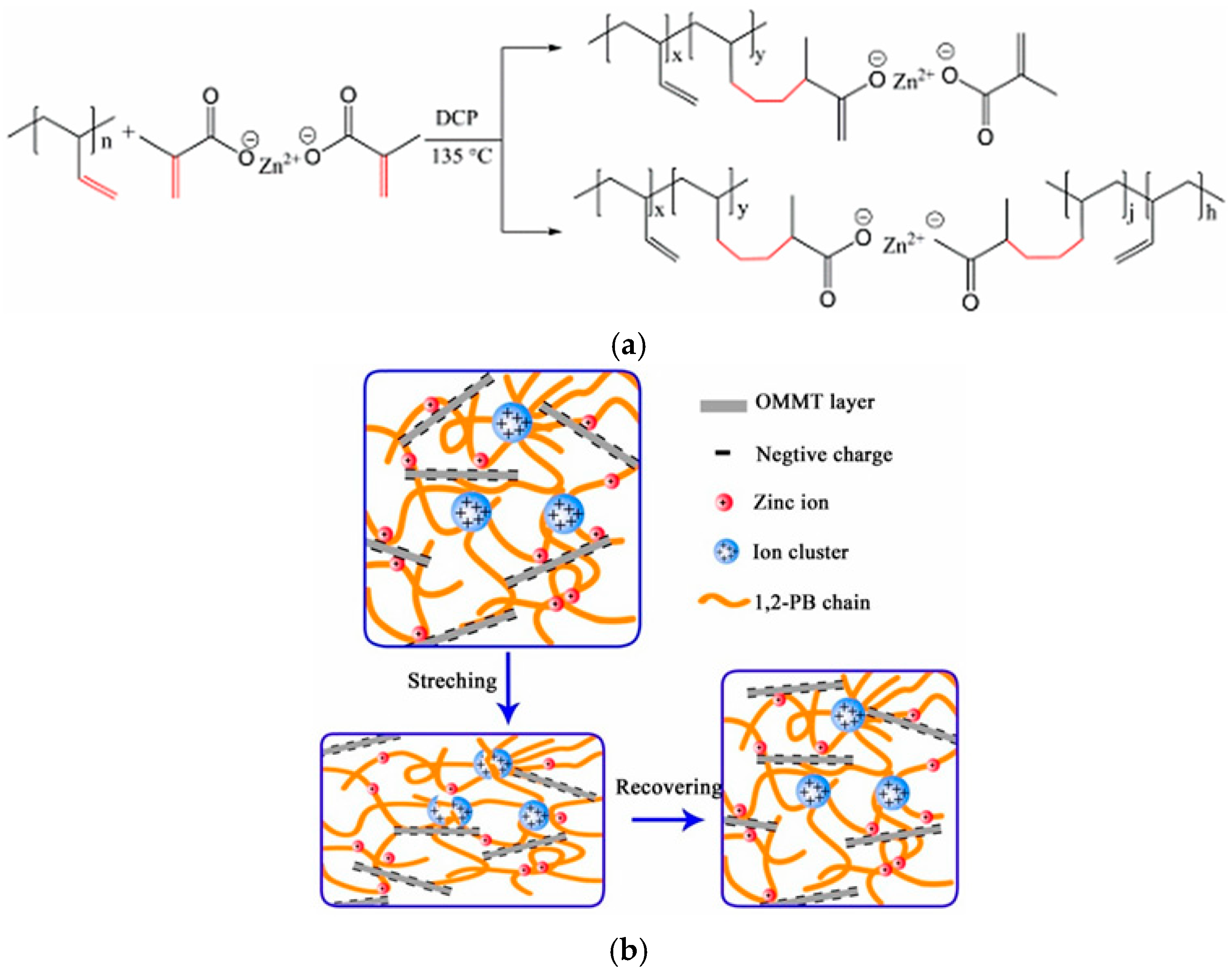

- Liu, J.; Li, D.; Zhao, X.; Geng, J.; Hua, J.; Wang, X. Buildup of Multi-Ionic Supramolecular Network Facilitated by In-Situ Intercalated Organic Montmorillonite in 1,2-Polybutadiene. Polymers 2019, 11, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.R.; Pham, T.H.; Nederstedt, H.; Jannasch, P. Durable and Highly Proton Conducting Poly(arylene perfluorophenylphosphonic acid) Membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 623, 119074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, V.; Lee, A.S.; Park, E.J.; Maurya, S.; Baca, E.D.; Fujimoto, C.; Hibbs, M.; Matanovic, I.; Kerres, J.; Kim, Y.S. Synergistically Integrated Phosphonated Poly(pentafluorostyrene) for Fuel Cells. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.; Lim, K.H.; Maurya, S.; Manriquez, L.D.; Atanasov, V.; Ahn, C.-H.; Hwang, S.S.; Lee, A.S.; Kim, Y.S. Dispersing Agents Impact Performance of Protonated Phosphonic Acid High-Temperature Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 1642–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, I.; Takamuku, S.; Jankova, K.; Jannasch, P.; Hvilsted, S. Proton Conducting Graft Copolymers with Tunable Length and Density of Phosphonated Side Chains for Fuel Cell Membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 450, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S.; Jung, J.; Koo, M.B.; Kim, J.G.; Gu, J.; Choi, G.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.F.; Ahn, C.-H.; Hwang, S.S.; et al. All Protonated Phosphonic Acid Membrane and Ionomers for High Powered Intermediate Temperature Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 522, 167336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Liu, H.; Han, S.; Yue, B.; Yan, L. Hydrogen Bond and Proton Transport in Acid–Base Complexes and Amphoteric Molecules by Density Functional Theory Calculations and 1H and 31P Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 16345–16355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunagiri, K.; Wong, A.J.-W.; Briceno-Mena, L.; Elsayed, H.M.G.H.; Romagnoli, J.A.; Janika, M.J.; Arges, C.G. Deconvoluting Charge-Transfer, Mass Transfer, and Ohmic Resistances in Phosphonic Acid–Sulfonic Acid Ionomer Binders Used in Electrochemical Hydrogen Pumps. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 5916–5932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigg, E.B.; Tiegs, B.J.; Coates, G.W.; Winey, K.I. High Morphological Order in a Nearly Precise Acid-Containing Polymer and Ionomer. ACS Macro Lett. 2017, 6, 947–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Z.; Sannigrahi, A.; Jannasch, P. Poly(tetrafluorostyrenephosphonic acid)−Polysulfone Block Copolymers and Membranes. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2013, 51, 4657–4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, V.; Kerres, J. Highly Phosphonated Polypentafluorostyrene. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 6416–6423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blidi, I.; Geagea, R.; Coutelier, O.; Mazières, S.; Violleau, F.; Destarac, M. Aqueous RAFT/MADIX Polymerisation of Vinylphosphonic Acid. Polym. Chem. 2012, 3, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, R.; Elomaa, M.; Jannasch, P. Nanostructured Proton Conducting Polystyrene-Poly(vinylphosphonic acid) Block Copolymers Prepared via Sequential Anionic Polymerizations. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 5146–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutevin, B.; Hervaud, Y.; Boulahna, A.; El Asri, M. Free-Radical Polymerization of Dimethyl Vinylbenzylphosphonate Controlled by TEMPO. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 6511–6516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, G.; Negrell-Guirao, C.; Iftene, F.; Boutevin, B.; Chougrani, K. Recent Progress on Phosphonate Vinyl Monomers and Polymers Therefore Obtained by Radical (Co)Polymerization. Polym. Chem. 2012, 3, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subianto, S.; Choudhury, N.R.; Dutta, N.K. Palladium Catalyzed Phosphonation of SEBS Block Copolymer. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2008, 46, 5431–5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvole, J.; Jannasch, P. Polysulfones Grafted with Poly(vinylphosphonic acid) for Highly Proton Conducting Fuel Cell Membranes in the Hydrated and Nominally Dry State. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 3893–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, V.; Oleynikov, A.; Xia, J.; Lyonnard, S.; Kerres, J. Phosphonic Acid Functionalized Poly(pentafluorostyrene) as Poly electrolyte Membrane for Fuel Cell Application. J. Power Sources 2017, 343, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Kim, S.Y.; Jung, H.Y.; Park, M.J. Phosphonated Polymers with Fine-Tuned Ion Clustering Behavior: Toward Efficient Proton Conductors. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 1120–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Guan, J.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Zheng, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, S. Phosphonated Ionomers of Intrinsic Microporosity with Partially Ordered Structure for High-Temperature Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. ACS Cent. Sci. 2023, 9, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davletbaeva, I.M.; Sazonov, O.O.; Zakirov, I.N.; Davletbaev, R.S.; Efimov, S.V.; Klochkov, V.V. Catalytic Etherification of ortho-Phosphoric Acid for the Synthesis of Polyurethane Ionomer Films. Polymers 2022, 14, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davletbaeva, I.M.; Sazonov, O.O.; Zakirov, I.N.; Arkhipov, A.V.; Davletbaev, R.S. Self-Organization of Polyurethane Ionomers Based on Organophosphorus-Branched Polyols. Polymers 2024, 16, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davletbaeva, I.M.; Sazonov, O.O.; Fazlyev, A.R.; Davletbaev, R.S.; Efimov, S.V.; Klochkov, V.V. Polyurethane Ionomers Based on Amino Ethers of orto-Phosphoric Acid. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 18599–18608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davletbaeva, I.M.; Sazonov, O.O.; Fazlyev, A.R.; Zakirov, I.N.; Davletbaev, R.S.; Efimov, S.V.; Klochkov, V.V. Thermal Behavior of Polyurethane Ionomers Based on Amino Ethers of Orthophosphoric Acid. Polym. Sci. Ser. A 2020, 62, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davletbaeva, I.; Sazonov, O.; Nikitina, E.; Kapralova, V.; Nizamov, A.; Akhmetov, I.; Arkhipov, A.; Sudar, N. Dielectric Properties of Organophosphorus Polyurethane Ionomers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davletbaeva, I.M.; Nizamov, A.A.; Yudina, A.V.; Baymuratova, G.R.; Yarmolenko, O.V.; Sazonov, O.O.; Davletbaev, R.S. Gel-Polymer Electrolytes Based on Polyurethane Ionomers for Lithium Power Sources. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 21548–21559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davletbaeva, I.M.; Nizamov, A.A.; Yarmolenko, O.V.; Sazonov, O.O.; Davletbaev, R.S. Gel-Polymer Electrolytes Based on Organophosphorus Polyurethanes for Lithium Power Sources. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e57372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davletbaeva, I.M.; Emelina, O.Y.; Vorotyntsev, I.V.; Davletbaev, R.S.; Grebennikova, E.S.; Petukhov, A.N.; Ahkmetshina, A.I.; Sazanova, T.S.; Loskutov, V.V. Synthesis and Properties of Novel Polyurethanes Based on Amino Ethers of Boron Acid for Gas Separation Membranes. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 65674–65683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davletbaeva, I.M.; Nurgaliyeva, G.R.; Akhmetshina, A.I.; Davletbaev, R.S.; Atlaskin, A.A.; Sazanova, T.S.; Efimov, S.V.; Klochkov, V.V.; Vorotyntsev, I.V. Porous Polyurethanes Based on Hyperbranched Amino Ethers of Boric Acid. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 111109–111119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davletbaeva, I.M.; Dulmaev, S.E.; Sazonov, O.O.; Klinov, A.V.; Davletbaev, R.S.; Gumerov, A.M. Water Vapor Permeable Polyurethane Films Based on the Hyperbranched Aminoethers of Boric Acid. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 23535–23544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davletbaeva, I.M.; Sazonov, O.O.; Dulmaev, S.E.; Klinov, A.V.; Fazlyev, A.R.; Davletbaev, R.S.; Efimov, S.V.; Klochkov, V.V. Pervaporation Polyurethane Membranes Based on Hyperbranched Organoboron Polyols. Membranes 2022, 12, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, S.D.T.; Wills, C.; Dixon, C.M.; Waddell, P.G.; Knight, J.G.; Mamlouk, M.; Doherty, S. Structure–Stability Correlations on Quaternary Ammonium Cations as Model Monomers for Anion-Exchange Membranes and Ionomers. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 9718–9730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Głowińska, A.; Trochimczuk, A.W. Polymer-Supported Phosphoric, Phosphonic and Phosphinic Acids—From Synthesis to Properties and Applications in Separation Processes. Molecules 2020, 25, 4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiller, J.C.; Liao, C.-J.; Lewis, K.; Klibanov, A.M. Designing Surfaces That Kill Bacteria on Contact. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 5981–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Bonilla, A.; Fernández-García, M. Polymeric Materials with Antimicrobial Activity. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 281–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, M.; Berti, C.; Binassi, E.; Fiorini, M.; Sullalti, S.; Acquasanta, F.; Vannini, M.; Di Gioia, D.; Aloisio, I.; Karanam, S.; et al. Synthesis and Characterization of Imidazolium Telechelic Poly(butylene terephthalate) for Antimicrobial Applications. React. Funct. Polym. 2012, 72, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.D.; Wilker, J.J. Underwater Bonding with Charged Polymer Mimics of Marine Mussel Adhesive Proteins. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 5085–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salma, U.; Shalahin, N. A Mini-Review on Alkaline Stability of Imidazolium Cations and Imidazolium-Based Anion Exchange Membranes. Results Mater. 2023, 17, 100366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Improving Markets for Recycled Plastics: Trends, Prospects and Policy Responses; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mikitaev, M.A.; Borukaev, T.A. Polybutylene Terephthalate (PBT), Synthesis and Properties. In Polymer Research Developments; Zaikov, G.E., Ed.; Hotei Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 1–206. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, C.W.; Roujeinikova, A.; Sedelnikova, S.; Baker, P.J.; Stuitje, A.R.; Slabas, A.R.; Rice, D.W.; Rafferty, J.B. Molecular Basis of Triclosan Activity. Nature 1999, 398, 383–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worley, S.D.; Sun, G. Improving Functional Characteristics of Wool and Some Synthetic Fibres. Trends Polym. Sci. 1996, 4, 364–370. [Google Scholar]

- Kenawy, E.-R.; Worley, S.D.; Broughton, R. The Chemistry and Applications of Antimicrobial Polymers: A State-of-the-Art Review. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 1359–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viscardi, G.; Quagliotto, P.; Barolo, C.; Savarino, P.; Barni, E.; Fisicaro, E. Synthesis and Surface and Antimicrobial Properties of Novel Cationic Surfactants. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 8197–8203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszak-Humienik, M. On the Thermal Stability of Some Ammonium Salts. Thermochim. Acta 2001, 378, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.H.; Mathias, L.J.; Gilman, J.W.; Schiraldi, D.A.; Shields, J.R.; Trulove, P.; Sutto, T.E.; DeLong, H.C. Effects of Melt-Processing Conditions on the Quality of Poly(ethylene terephthalate) Montmorillonite Clay Nanocomposites. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2002, 40, 2661–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demberelnyamba, D.; Kim, K.-S.; Park, S.-Y.; Lee, H.; Kim, C.-J.; Yoo, I.-D. Synthesis and Antimicrobial Properties of Imidazolium and Pyrrolidinonium Salts. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colonna, M.; Berti, C.; Binassi, E.; Fiorini, M.; Sullalti, S.; Acquasanta, F.; Vannini, M.; Di Gioia, D.; Aloisio, I. Imidazolium Poly(butylene terephthalate) Ionomers with Long-Term Antimicrobial Activity. Polymer 2012, 53, 1823–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, L. Ionic Polymers, 1st ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, A. Introduction to Ionomers; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, T.; Tsou, A.; Webb, R. Ion Exchange. In Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Zapp, R.L.; Hous, P. Butyl and Halobutyl Rubbers. In Rubber Technology, 2nd ed.; Morton, M., Ed.; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1973; pp. 249–273. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska, A.; Zalewska, A.; Skalska, A.; Ostrowski, A.; Kowalak, S. Proton Conductivity of Imidazole Entrapped in Microporous Molecular Sieves. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 2475–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, J.S.; White, G.D.; Thom, D.; Whitney, R.A.; Hopkins, W. Sulfuration and Reversion Reactions of Brominated Poly(isobutylene-co-isoprene). J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2003, 41, 1915–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantman, C.W.; MacKnight, W.J.; Higgins, J.S.; Peiffer, D.G.; Sinha, S.K.; Lundberg, R.D. Small-Angle Neutron Scattering from Sulfonate Ionomer Solutions. 1. Associating Polymer Behavior. Macromolecules 1988, 21, 1339–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleczek, M.R.; Whitney, R.A.; Daugulis, A.J.; Parent, J.S. Synthesis and Characterization of Thermoset Imidazolium Bromide Ionomers. React. Funct. Polym. 2016, 106, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, S.; Anderson, D.G.; Langer, R. Physical and mechanical properties of PLA, and their functions in widespread applications Acomprehensive review. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hu, K.; Sun, S.-T.; Jiang, H.; Huang, D.; Zhang, K.Y.; Pan, L.; Li, Y.-S. Toughening Poly(lactic acid) with Imidazolium based Elastomeric Ionomers. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2018, 36, 1342–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ding, Y.; Jiang, H.; Sun, S.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, K.; Pan, L.; Li, Y. Functionalized Elastomeric Ionomers Used as Effective Toughening Agents for Poly(lactic acid): Enhancement in Interfacial Adhesion and Mechanical Performance. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zou, W.; Luo, Y.; Xie, T. Shape Memory Polymer Network with Thermally Distinct Elasticity and Plasticity. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J. Supramolecular Shape Memory Polymers. In Advances in Shape Memory Polymers; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Behl, M.; Lendlein, A. Shape-Memory Polymers. Mater. Today 2007, 10, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.M.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.C.; Ding, Z.; Purnawali, H.; Tang, C.; Zhang, J.L. Thermo/Chemo-Responsive Shape Memory Effect in Polymers: A Sketch of Working Mechanisms, Fundamentals and Optimization. J. Polym. Res. 2012, 19, 9952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Lan, X.; Liu, Y.; Du, S. Shape-memory polymers and their composites: Stimulus methods and applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2011, 56, 1077–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilate, F.; Mincheva, R.; De Winter, J.; Gerbaux, P.; Wu, L.; Todd, R.; Raquez, J.-M.; Dubois, P. Design of Multistimuli-Responsive Shape-Memory Polymer Materials by Reactive Extrusion. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 5860–5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehn, J.-M. From supramolecular chemistry towards constitu tional dynamic chemistry and adaptive chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Wang, F.; Zheng, B.; Huang, F. Stimuli-responsive supramolecular polymeric materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 6042–6065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karger-Kocsis, J.; Kéki, S. Biodegradable polyester-based shape memory polymers: Concepts of (supra)molecular architecturing. Express Polym. Lett. 2014, 8, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiffert, S.; Sprakel, J. Physical chemistry of supramolecular polymer networks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtecki, R.J.; Meador, M.A.; Rowan, S.J. Using the dynamic bond to access macroscopically responsive structurally dynamic polymers. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.; Herrera, R.; Archer, L.A.; Giannelis, E.P. Nanoscale Ionic Materials. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 4353–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.; Herrera, R.; Bourlinos, A.B.; Li, R.; Amassian, A.; Archer, L.A.; Giannelis, E.P. The synthesis and properties of nanoscale ionic materials. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2010, 24, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, N.J.; Akbarzadeh, J.; Peterlik, H.; Giannelis, E.P. Synthesis and Properties of Highly Dispersed Ionic Silica−Poly (ethylene oxide) Nanohybrids. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 1265–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, N.J.; Wallin, T.J.; Vaia, R.A.; Koerner, H.; Giannelis, E.P. Nanoscale Ionic Materials. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, M.L.; Mirau, P.A.; Meerwall, E.v.; Vaia, R.A.; Rodriguez, R.; Giannelis, E.P. Canopy Dynamics in Nanoscale Ionic Materials. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3735–3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourlinos, A.B.; Herrera, R.; Chalkias, N.; Jiang, D.D.; Zhang, Q.; Archer, L.A.; Giannelis, E.P. Surface-Functionalized Nanoparticles with Liquid-Like Behavior. Adv. Mater. 2005, 17, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odent, J.; Raquez, J.-M.; Samuel, C.; Barrau, S.; Enotiadis, A.; Dubois, P.; Giannelis, E.P. Shape-Memory Behavior of Polylactide/Silica Ionic Hybrids. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 2896–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odent, J.; Raquez, J.-M.; Dubois, P.; Giannelis, E.P. Ultra-Stretchable Ionic Nanocomposites: From Dynamic Bonding to Multi-Responsive Behavior. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 13357–13363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Pagels, M.K.; Jeon, J.Y.; Bae, C. Ionomers for Electrochemical Energy Conversion & Storage Technologies. Polymer 2020, 211, 123080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusoglu, A.; Weber, A.Z. New Insights into Perfluorinated Sulfonic-Acid Ionomers. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 987–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Lee, Y.M. Anion Exchange Polyelectrolytes for Membranes and Ionomers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2021, 11, 101345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohma, A.; Fushinobu, K.; Okazaki, K. Influence of Nafion® Film on Oxygen Reduction Reaction and Hydrogen Peroxide Formation on Pt Electrode for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 8829–8838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, S.P. Second-Coordination Sphere Effects on Selectivity and Specificity of Heme and Nonheme Iron Enzymes. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 5308–5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shook, R.L.; Borovik, A.S. Role of the Secondary Coordination Sphere in Metal-Mediated Dioxygen Activation. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 3646–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, C.; Jaramillo, T.F. Using Microenvironments to Control Reactivity in CO2 Electrocatalysis. Joule 2020, 4, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Bao, X. Confined Microenvironment for Catalysis Control. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 834–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, H.; Kutz, R.; Masel, R.I. CO2 Electrolysis to CO and O2 at High Selectivity, Stability and Efficiency Using Sustainion Membranes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, J3371–J3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, G.P.S.; Schreier, M.; Vasilyev, D.; Scopelliti, R.; Grätzel, M.; Dyson, P.J. New Insights into the Role of Imidazolium-Based Promoters for the Electroreduction of CO2 on a Silver Electrode. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7820–7823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.; Kumar, D.; Gil-Sepulcre, M.; Nippe, M. Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction by Imidazolium-Functionalized Molecular Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13993–13996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.-F.; Horne, M.; Bond, A.M.; Zhang, J. Is the Imidazolium Cation a Unique Promoter for Electrocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide? J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 23989–24001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshy, D.M.; Akhade, S.A.; Shugar, A.; Abiose, K.; Shi, J.; Liang, S.; Oakdale, J.S.; Weitzner, S.E.; Varley, J.B.; Duoss, E.B.; et al. Chemical Modifications of Ag Catalyst Surfaces with Imidazolium Ionomers Modulate H2 Evolution Rates during Electrochemical CO2 Reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 14712–14725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchi, K.A. Synthesis and Polymerization of Substituted Ammonium Sulfonate Monomers for Advanced Materials Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, L.A.; Dufour, B.; Matyjaszewski, K. Incorpo ration of Poly(2-Acryloamido-2-Methyl-N-Propanesulfonic Acid) Segments into Block and Brush Copolymers by ATRP. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2009, 47, 5386–5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consolante, V.; Marić, M. Nitroxide-Mediated Polymerization of an Organo-Soluble Protected Styrene Sulfonate: Development of Homo- and Random Copolymers. Macromol. React. Eng. 2011, 5, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pollock, K.L.; Cavicchi, K.A. Synthesis of Poly(trioctylammonium P-Styrenesulfonate) Homopolymers and Block Copolymers by RAFT Polymerization. Polymer 2009, 50, 6212–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R.A.; Fitzgerald, J.J.; Kim, D. Viscoelastic Behavior of Lightly Sulfonated Polystyrene Ionomers. Macromolecules 1991, 24, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]