1. Introduction

Currently, the dependency on petroleum-derived plastics within packaging systems is primarily attributable to their exceptional barrier characteristics, technological adaptability, affordability, and production scalability [

1]. This worldwide reliance has already culminated in a surge in production volumes, which ascended to 413.8 Mt (million tonnes) in 2023, thereby corroborating forecasts that by 2040, the production and processing of plastics could constitute as much as 20% of global oil consumption [

2,

3]. It is imperative to acknowledge that such reliance incurs significant environmental ramifications, as a considerable fraction of plastic waste is either incinerated or released without regulation into the environment, inflicting severe harm on ecosystems and posing considerable threats to public health [

4]. For instance, it is extensively documented that numerous types of packaging plastics incorporate plasticizers and stabilizers, including phthalates and bisphenol A [

5,

6]. Over time, these substances have been shown to migrate into food and beverages, which has been associated with endocrine disruption, reproductive health issues, and an elevated risk of oncological disorders [

5].

The pressing necessity to alleviate environmental impact and diminish health-associated hazards propels the exploration of renewable, low-carbon, and potentially carbon-neutral materials [

7]. Within the plethora of candidates, cellulose is particularly notable due to its natural prevalence, carbon neutrality, and ecological suitability (

Figure 1a) [

8,

9]. Beyond its origin from plant sources, cellulose can also be biosynthesized by microorganisms as a defensive metabolic strategy, resulting in the formation of bacterial cellulose (BC) [

9]. BC was first identified in the late nineteenth century, yet its significance as a versatile biomaterial unfolded gradually through key scientific and technological advances (

Figure 1b) [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Early visualization of its unique nanofibrous architecture and later insights into cellulose synthase activity established the foundation for understanding BC biosynthesis [

11]. By the late twentieth century, BC had already entered commercial use in both food products and biomedical applications, demonstrating its safety and biocompatibility [

12]. The following decades expanded its scope: genetic engineering approaches were proposed to enhance microbial productivity, and applications diversified from acoustic membranes to sustainable packaging solutions [

13]. More recently, regulatory and environmental drivers, such as the European Parliament’s directive restricting single-use plastics, have further accelerated interest in BC as an eco-friendly alternative to petroleum-derived polymers [

14,

15]. These milestones collectively highlight BC’s progression from a biological curiosity to a promising platform for next-generation sustainable materials.

Recent advancements in biotechnology, material science, and sustainable engineering have significantly expanded the potential applications of BC beyond its conventional biomedical and food uses [

15]. The integration of synthetic biology, green chemistry, and nanotechnology has facilitated the development of multifunctional BC-based composites with adjustable mechanical, optical, and antimicrobial characteristics [

16]. These advances align with a transformative shift in packaging science, moving from passive containment to active, intelligent, and biodegradable systems that preserve food quality while mitigating environmental impacts [

17]. In this context, BC has emerged as a crucial platform for the next generation of high-performance, environmentally sustainable packaging materials [

18].

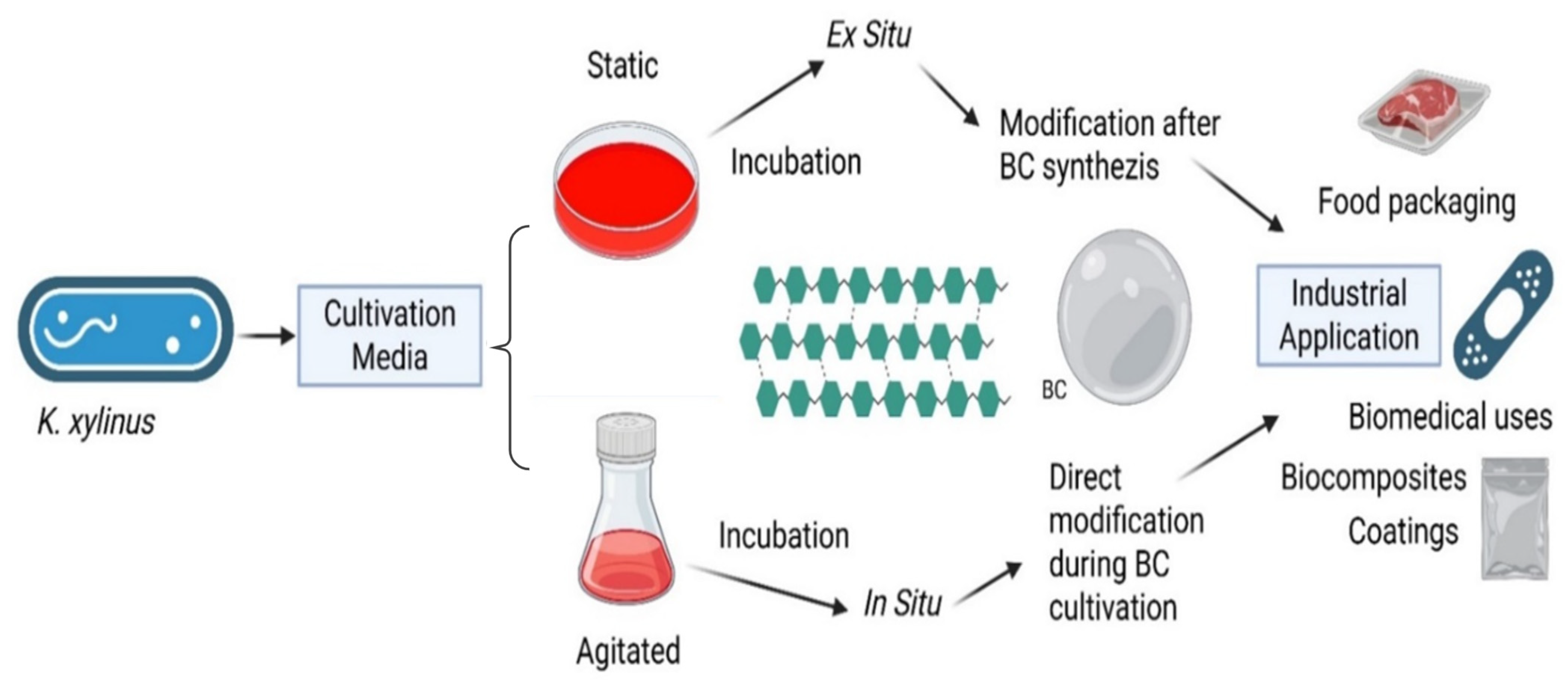

Against this backdrop, and in contrast to previous reviews that addressed bacterial cellulose either from a bioprocessing perspective [

19] or from a materials engineering standpoint [

18,

20], the present work provides an integrative framework linking the genetic and biochemical foundations of BC biosynthesis with its structural hierarchy, modification chemistry, and packaging functionality. By systematically distinguishing in situ (modified-medium, aerosol-assisted, and 3D biofabrication) from ex situ (impregnation, casting, vacuum filtration, and electrospinning) strategies, this review develops a multiscale understanding of how each route modulates nanostructure, mechanical reinforcement, and active or intelligent behavior in food-packaging systems. Moreover, unlike bibliometric or single-domain analyses [

21,

22], this article couples bioprocess optimization, metabolic engineering, and circular bioeconomy concepts to delineate practical pathways toward cost-efficient, low-carbon BC bioplastics. Collectively, it consolidates dispersed advances into a coherent perspective that bridges microbial synthesis, functional modification, and application-oriented performance, defining the foundations for industrial translation of BC-based sustainable packaging.

The aim of this review is to deliver a focused and methodologically transparent synthesis of recent advances in bacterial cellulose production and its translation to sustainable food packaging, and to make clear why an updated analysis is needed now. Unlike prior narratives that treated bioprocessing or materials design in isolation, we connect microbial genetics and fermentation platforms to structural hierarchy and packaging performance, with specific attention to emerging routes such as aerosol-assisted biosynthesis and three-dimensional biofabrication. We map how feedstock choices, reactor modes, and strain engineering in Komagataeibacter xylinus and related genera shape fibril architecture and crystallinity, then show how in situ and ex situ modification pathways deliver mechanical reinforcement, barrier control, antioxidant function, antimicrobial efficacy including synergy concepts, and intelligent sensing. We clarify that native bacterial cellulose suffers from specific limitations such as insufficient moisture resistance, restricted flexibility, and modest gas barrier performance, which necessitate the modification strategies discussed throughout the review. We also integrate cross-cutting dimensions that are often fragmented across the literature, including circular bioeconomy substrates, passive radiative cooling films, and the regulatory and techno-economic constraints that govern industrial adoption. By articulating these connections and gaps, the review explains where BC packaging performs well, where it fails, and which process or chemistry levers are most likely to close the remaining cost, durability, and compliance barriers.

2. Materials and Methods

Following PRISMA guidance, we searched PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection, and Scopus for records from January 1960 to November 2025. The search combined controlled vocabulary and free-text terms. Core keywords included: “bacterial cellulose”, “BC”, “Komagataeibacter”, “Gluconacetobacter”, “static culture”, “agitated culture”, “stirred-tank”, “bioreactor”, “Hestrin–Schramm”, “agro-waste”, “glycerol”, “corn steep liquor”, “in situ modification”, “ex situ modification”, “impregnation”, “casting”, “vacuum filtration”, “electrospinning”, “mechanical properties”, “oxygen transmission rate”, “water vapor transmission rate”, “antimicrobial”, “antioxidant”, “intelligent packaging”, and “food packaging”.

Inclusion criteria were: peer-reviewed English articles that focused on bacterial cellulose; reported bioproduction or fermentation parameters; and/or provided structural, physicochemical, or packaging-relevant performance data. Study types included original research, systematic reviews, and high-quality tutorials with experimental details. Exclusion criteria were: non-BCs without separable BC data; conference abstracts without full texts; theses, patents, and editorials; non-English unless uniquely informative; and duplicate or retracted items. From the eligible studies we extracted strain and culture mode, vessel or bioreactor, media and carbon or nitrogen sources, process conditions, yields, crystallinity or degree of polymerization when available, morphology, purification, modification route and technique, composition, and packaging metrics such as tensile properties, oxygen and water vapor transmission, antimicrobial or antioxidant activity, and shelf-life outcomes.

3. Bioproduction and Fermentation Strategies of BC

Among all microorganisms capable of synthesizing cellulose, which includes both fungal and algal species, bacteria have been recognized as the most adept and controllable producers, with

K. xylinus distinguished as the model organism [

23]. This superiority can be explained by its distinct microbiological and genetic properties [

24]. From a microbiological standpoint,

K. xylinus is classified as a Gram-negative obligate aerobe exhibiting a highly efficient central metabolic pathway, which enables the ongoing production of cellulose from a wide variety of carbon and nitrogen sources [

11]. Genetically, its genome is notable for containing multiple copies of the

bcs operon, which encodes the cellulose synthase complex (

bcsA,

bcsB) along with auxiliary proteins (

bcsC,

bcsD) that facilitate the export and crystallization of

β 1,4 glucan chains, thereby promoting robust fibril formation [

11,

25]. Physiologically,

K. xylinus is characterized by its stability, as strains can be maintained 1t low temperatures while preserving their cellulose-synthesizing abilities [

11]. Collectively, these characteristics confer exceptional metabolic efficiency, genetic specialization, and storage stability, thereby establishing

K. xylinus as the most thoroughly documented and extensively employed bacterial species for cellulose production across a range of applications in the fields of food, medicine, and sustainable packaging.

The conventional Hestrin Schramm (HS) medium persists as the standard for bacterial cellulose fermentation within laboratory contexts; nevertheless, its economic feasibility is limited because glucose accounts for nearly 65 percent of total production costs [

26]. Consequently, scholars have investigated a wide variety of agro-industrial byproducts as alternative feedstocks, including fruit pomace, tobacco stalks, cotton waste, sugarcane bagasse, dairy whey, brewery by-products, and crude glycerol (Gly) obtained from biodiesel production [

19,

20,

21,

22]. These residues are nutritionally useful because they naturally contain the primary metabolites required for

Komagataeibacter growth and cellulose biosynthesis. Fruit and sugarcane residues supply readily fermentable sugars, dairy whey contributes nitrogen and lactose, and crude Gly or brewery waste provides reduced carbon sources that support efficient energy generation and metabolic flux through cellulose-producing pathways [

18,

25,

26]. Hence, the selection of substrates reflects both the biochemical composition of the waste and its compatibility with microbial metabolism in

Komagataeibacter [

21,

22,

26]. Additionally, the valorization of these residues promotes fermentation processes that address disposal challenges and lower environmental burdens, which aligns with the principles of the circular economy by converting low-value waste streams into high-value biomaterials [

27,

28].

The biosynthetic mechanism of bacterial cellulose occurs through two intricately synchronized phases, namely the intracellular polymerization of UDP glucose and the extracellular hierarchical assembly of fibrils; this dual process culminates in a remarkably organized nanostructure that differentiates it from cellulose obtained through plant extraction or chemical regeneration [

11]. Specifically, the secreted subfibrils autonomously coalesce into nanofibrils, nanoribbons, and ultimately construct a three-dimensional porous network characterized by high crystallinity and consistent orientation [

29]. In contrast, cellulose derived from plants is embedded within a lignocellulosic matrix that comprises lignin, hemicellulose, and pectin, necessitating rigorous chemical and thermal treatments that compromise structural integrity and diminish purity [

30]. Similarly, regenerated cellulose, which is synthesized through chemical dissolution followed by reprecipitation, lacks the same nanoscale alignment, resulting in reduced crystallinity and inferior mechanical properties [

31]. Consequently, the biosynthetic route of BC endows it with a defect-free nanofibrillar framework exhibiting superior structural alignment and moisture affinity, thereby outperforming plant-derived celluloses in both integrity and interfacial functionality [

32,

33,

34].

Two main fermentation strategies for bacterial cellulose production are static and agitated cultures. In static culture, cellulose forms continuous films at the air–liquid interface under aerobic conditions, yielding highly crystalline and uniform materials suitable for food packaging and biomedical use [

35]. Conversely, agitated culture produces irregular morphologies such as pellets and aggregates, and although agitation improves oxygen transfer, it also redirects metabolism toward complete oxidation in the tricarboxylic acid cycle, which reduces cellulose yield [

36,

37]. Consequently, when evaluating these methodologies, static culture demonstrates superior productivity and structural quality, whereas agitated culture may only be beneficial in particular bioprocess designs that necessitate diverse morphologies. The key differences between these two strategies, including microbial strain, culture type, yield, fermentation duration, and product crystallinity, are summarized in

Table 1, which emphasizes their relative industrial advantages and limitations.

Another critical distinction lies in the purification process. Plant derived cellulose is tightly associated with lignin, hemicellulose, and pectin within the lignocellulosic matrix, and therefore its extraction requires high temperatures, aggressive chemical reagents, and energy intensive treatments that compromise both sustainability and cost effectiveness [

38]. In contrast, bacterial cellulose is secreted in a nearly pure form, and its purification can be accomplished simply by washing with deionized water to remove residual bacterial cells and medium components [

11,

24,

25,

26]. As a result, BC demonstrates a clear environmental advantage, since its recovery minimizes chemical usage, reduces energy consumption, and aligns with eco-friendly bioprocessing principles [

22,

23,

24].

Analysis of publication trends (

Figure 2) reveals a gradual increase in bacterial cellulose research from 1960 onward, followed by a dramatic rise after 2019. This acceleration is closely linked to policy and market pressures within the food-packaging sector, particularly the European Union directive restricting single-use plastics and the global demand for renewable materials with lower environmental impact [

2,

3,

39,

40]. For instance, the expansion of the bioeconomy agenda, the introduction of international funding initiatives supporting green materials, and the development of advanced nanotechnology platforms that highlighted BC’s biomedical and packaging potential collectively accelerated scientific attention [

39]. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic emphasized the demand for safer and biocompatible materials in medical applications, which indirectly stimulated research in microbial cellulose [

40]. Collectively, these drivers clarify why BC has become a rapidly growing focus in sustainable food-packaging research, not solely biomedical materials.

Although BC exhibits superior properties, its large-scale production remains limited due to high costs and relatively low yields [

41,

42]. The standard HS medium alone can account for nearly 30% of total expenses [

43], and typical yields rarely exceed 20 g/L, which is insufficient for industrial applications. Static culture offers high-quality pellicles but is constrained by oxygen diffusion and extended incubation periods that hinder scalability. To overcome these limitations, researchers have implemented bioreactor systems, fed-batch fermentation, and statistical optimization through response surface methodology. Bioreactors allow precise control of temperature, pH, and oxygen levels but often fail to reproduce the microstructure obtained under static conditions [

41]. Fed-batch and intermittent feeding techniques maintain nutrient availability, enhancing productivity [

44]. Further optimization of temperature, pH, and oxygen conditions has been achieved using response surface methodology [

45]. Recent efforts have also emphasized replacing conventional nutrients with cost-effective alternatives [

21]. Emerging technologies such as cell-free gene expression systems utilize bacterial extracts instead of live cells, offering new opportunities to circumvent the limitations of traditional fermentation and potentially improve process efficiency and scalability [

46,

47]. Ongoing research is directed toward improving production platforms, refining fermentation conditions, and applying genetic and metabolic engineering strategies to maximize BC yield while minimizing cost [

25,

48]. In this context, laboratory-scale advances provide valuable insights into improving BC biosynthesis, but they primarily reflect optimizations within controlled experimental settings rather than evidence of broader application trends or market-driven expansion.

Recent laboratory studies have also demonstrated optimized static cultivation approaches, as illustrated below. An example of the static cultivation process was described by Saavedra-Sanabria et al. [

49], who cultivated

G. xylinus strains preserved in 10% Gly at −80 °C. Frozen strains were reactivated in fresh HS medium at 30 °C with shaking for 7 d, followed by preparation of seed cultures in 150 mL HS medium incubated at 150 rpm and 30 °C for 48 h. A suspension containing 1 × 10

5 CFU mL

−1 was inoculated into bioreactor flasks containing 30 mL of nutrient medium and 3 mL of seed culture. The mixture was adjusted to pH 5.5 and incubated statically at 30 °C for 15 d. BC pellicles were collected daily, and both pH and sugar consumption were monitored. After fermentation, the BC films were purified by boiling in deionized water for 30 min, followed by immersion in 5% sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) solution for 72 h, washing to neutral pH, sterilization at 121 °C for 15 min, and lyophilization under vacuum at −87 °C for 72 h (

Figure 3).

4. Structural Basis of BC

BC demonstrates a distinctive semicrystalline architecture that comprises both organized crystalline domains and disordered amorphous regions. In the crystalline domains,

β-1,4-glucan chains assume a highly ordered parallel configuration, which is stabilized by extensive networks of intra- and inter-chain hydrogen bonding, with each anhydroglucose unit contributing three reactive hydroxyl groups (C2, C3, C6). In contrast, the amorphous regions contain a greater abundance of free hydroxyl groups, which confer flexibility and hydrophilicity. Quantitative assessments have indicated that the crystallinity index of BC (84–90%) significantly surpasses that of cellulose derived from plants (40–60%), attributable to the superior enzymatic precision exhibited by cellulose synthase complexes during the biosynthetic process [

50]. The crystalline architecture of cellulose presents various polymorphic forms (I–V) that are contingent upon the orientation of hydrogen bonds within and between the chains. Despite both BC and plant cellulose exhibiting the cellulose I structure characterized by parallel-chain packing, their supramolecular organizations manifest substantial differences [

51,

52,

53]. The three-dimensional network of BC is constituted of nanofibers interconnected via intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonding, culminating in a high specific surface area (50–200 m

2 g

−1) and porosity exceeding 90% [

54,

55]. These microstructural attributes endow BC films with exceptional strength, elasticity, and reactivity in comparison to conventional plant cellulose.

Cellulose typically exists as a mixture of two crystalline allomorphs, namely Iα (triclinic) and I

β (monoclinic) [

51,

56]. The Iα phase is predominantly found in BC and certain algal celluloses, while the I

β phase is more characteristic of celluloses derived from plants [

56,

57]. These structural features and their distribution across bacterial and plant celluloses have long been recognized in classical cellulose science and form the basis for distinguishing microbial BC from lignocellulosic counterparts. For instance,

Gluconacetobacter hansenii NCIM 2529 yields a BC with a crystallinity reaching up to 81%, a predominant I

α phase, a Z-average particle size of 1.4 µm, and a porosity of 182% [

57]. The degree of polymerization (DP) for BC typically ranges from 2000 to 6000 glucose units, whereas plant cellulose exhibits significantly higher DPs (13,000–14,000) [

58]. Variations in DP and microstructure as a function of cultivation conditions have also been well established in foundational BC studies. Under static culture at pH 4,

Acetobacter xylinum synthesized BC with DP values of 14,000–16,000, whereas a moderate elevation to pH 5 diminished it to approximately 11,000 [

59]. These observations reflect classical experimental procedures widely used to investigate how pH, oxygen availability, and nutrient composition affect BC polymerization and microfibril assembly, rather than representing newly developed methods. These variations underscore the intricate relationship between cultivation parameters and the molecular architecture of BC.

BC films manifest a stratified three-dimensional nanostructure consisting of robust fibrils (150–160 nm) organized from diminutive nanofibrils (20–60 nm) that are formed from

β-1,4-glucan chains [

54,

60] (

Figure 4a). This intricate network bestows remarkable mechanical durability and contributes significantly to the high water-holding capacity (WHC) of BC [

61,

62]. The pores within BC range from nanometer to micrometer scale, with average mesopores measuring 21–26 nm and pore volumes between 0.024 and 0.11 cm

3 g

−1 [

63]. Typically, BC gels demonstrate WHC values ranging from 62.3 g·g

−1 in their hydrated state to 3.8 g·g

−1 post-drying [

60,

64]. On a dry-weight basis, newly synthesized BC possesses the capability to retain water at a ratio of 62 to over 100 times its weight, which corresponds to approximately 98.8% moisture content [

65,

66]. This extraordinary WHC is attributable to its three-dimensional nanostructure, extensive surface area, and the presence of numerous hydroxyl groups that facilitate the formation of hydrogen bonds [

67]. Various environmental factors also play a significant role in influencing WHC:

K. hansenii GA2016 cultivated on a fruit-peel medium exhibited a WHC of 627–928%, surpassing the 609% observed in HS medium, with fibril diameters ranging from 47 to 61 nm [

68]. In a similar vein,

Novacetimonas hansenii P3 cultivated on pomegranate waste exhibited a WHC of 554% alongside fibril widths of 50–70 nm [

69]. Water functions as a plasticizer, thereby augmenting flexibility and permeability (

Figure 4b) [

67,

68,

69,

70].

The production of BC is profoundly affected by the selection of carbon sources, which can constitute 30–65% of the total production expenses [

71,

72]. Frequently employed substrates encompass glucose, sucrose, fructose, and mannitol [

73,

74]. Glucose, recognized as the conventional carbon source for

A. xylinum, often results in the accumulation of gluconic acid, which subsequently lowers the pH of the culture medium and inhibits BC biosynthesis [

75]. Alternative carbon sources such as fructose and Gly can yield comparable outcomes; however, monosaccharides like galactose and xylose typically result in diminished productivity due to the slower growth rates of the bacteria. Notably, certain alternatives have exhibited enhanced efficiency; for example, D-arabitol has demonstrated a BC yield exceeding six times that of glucose in

A. xylinum KU-1 [

75,

76].

Despite its high yield, the cost-effectiveness of D-arabitol remains a limiting factor for large-scale BC production. Unlike glucose, which is produced on an industrial scale through starch hydrolysis and enzymatic saccharification, D-arabitol is primarily obtained from microbial fermentation of sugars such as D-glucose or D-xylose using

Candida and

Debaryomyces species. This additional bioconversion step increases production costs, making D-arabitol less economically competitive compared with conventional carbon sources. According to current market analyses, the price of D-arabitol remains several times higher than that of food-grade glucose, thereby constraining its feasibility for continuous fermentation systems where carbon source input strongly influences cost per gram of cellulose yield [

19,

20,

21,

22].

However, ongoing research seeks to improve its market accessibility by employing renewable feedstocks and engineered microbial routes for D-arabitol biosynthesis. For instance, lignocellulosic biomass hydrolysates and agricultural residues have been explored as inexpensive substrates for D-arabitol production, significantly lowering process costs while supporting circular bioeconomy principles. Thus, while D-arabitol demonstrates remarkable bioconversion efficiency and compatibility with BC-producing strains, its large-scale adoption will depend on future advances in low-cost biomanufacturing and supply chain availability that can match the affordability of glucose [

20,

21,

22].

To reduce production costs, recent studies categorize alternative feedstocks for

Komagataeibacter fermentation into three main groups of carbon sources. The first group includes fruit-derived substrates, such as pineapple peel juice, overripe fruit, and other sugar-rich residues, which provide readily fermentable monosaccharides and support high cellulose yields [

77]. The second group comprises agricultural wastes, including sugarcane juice, wheat straw hydrolysates, and coffee husks. These materials contain fermentable sugars and organic acids that can sustain microbial growth after appropriate pretreatment [

21]. The third group encompasses industrial by-products, most notably crude glycerol (Gly), corn steep liquor, fermentation residues from wine and beer, and cotton textile waste. These substrates offer reduced carbon compounds and nitrogen-rich components that enhance microbial metabolism and biomass formation [

21,

77]. The choice of carbon source not only affects productivity but also modulates the morphology and organization of BC fibrils. For example, BC synthesized from xylose forms less uniform microfibrils than cellulose produced from glucose [

75].

A. xylinum can metabolize a wide variety of these substrates through pathways such as the pentose phosphate pathway, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and gluconeogenesis, achieving an approximate carbon-to-cellulose conversion efficiency of 50 percent [

78].

Nitrogen sources are also integral to the biosynthesis of BC. Conventional nitrogen supplements, including yeast extract and peptone, are costly and may account for 50–65% of the overall production costs [

79,

80,

81]. To overcome this challenge, alternative, lower-cost nitrogen sources derived from waste materials have been investigated. A particularly effective substitute is corn steep liquor, a by-product of the starch industry [

82]. Additionally, coffee cherry husk extract has shown promise as a nutrient source, while sunflower meal hydrolysates, in combination with crude Gly and hydrolysates from confectionery waste, have each yielded approximately 13 g/L of BC [

83,

84].

Several additives are known to enhance BC yield and improve material properties. Ethanol, vitamins, agar, sodium alginate, sulfates, and phosphates have been frequently tested. Ethanol not only increases yield but also minimizes the occurrence of non-producing mutant strains in agitated cultures [

85]. Volova et al. [

86] observed that the addition of 3% ethanol to a glucose–Gly medium elevated BC production in

K. xylinus B-12068 to 2.4–3.3 g L

−1 d

−1. Vitamin additives can also promote productivity; for example, supplementation with 0.5% ascorbic acid doubled both BC yield and crystallinity in four

Gluconacetobacter xylinus strains [

87]. Modification of medium rheology using agar or sodium alginate, along with mineral additives such as sulfates and phosphates, has proven beneficial for improving BC synthesis [

85,

88]. In parallel, the selection of an appropriate carbon source must reflect realistic industrial availability; although pure glucose is frequently used in laboratory media, industrial processes increasingly rely on hydrolysates obtained from sugar-rich, starchy, or lignocellulosic feedstocks to reduce cost and ensure resource sustainability. Accordingly, optimization of carbon and nitrogen inputs must account for both biological performance and the techno-economic feasibility of sourcing hydrolysates rather than importing refined glucose. Current research focuses on cost-effective medium formulations and the integration of synthetic biology and metabolic engineering approaches for targeted pathway enhancement [

85,

89].

Building upon the previously described fermentation strategies, the operational parameters of static cultivation have been extensively optimized to maximize BC yield and crystallinity. Under typical conditions, cultures are maintained in shallow trays or flasks at 28–30 °C and pH 4–7 for 1–14 d without agitation. During fermentation, a dense pellicle develops at the air–liquid interface, where restricted oxygen diffusion often becomes a rate-limiting factor [

90,

91,

92]. To enhance productivity, several studies have explored temperature control and carbon-source variation. For instance, Sathianathan et al. [

69] isolated

N. hansenii P3 from decayed pomegranate fruit waste and achieved a yield of up to 3 g L

−1 of BC with a crystallinity index of 96% when cultivated in HS medium containing glucose and sucrose at 30 °C for 15 d.

Food-grade and waste-derived carbon sources can be categorized into three principal groups based on their carbohydrate composition and required processing steps: (i) sugar-containing materials (e.g., fruit juices, molasses, cane or beet syrups), which can be used directly after dilution; (ii) starchy materials (e.g., potato waste, cassava residues, corn by-products), which require enzymatic or acid hydrolysis to release fermentable sugars; (iii) cellulose-containing plant biomass (e.g., agricultural residues, fruit peels, brewery waste), which must undergo pretreatment and saccharification to generate glucose-rich hydrolysates. Such a classification enables a clearer evaluation of technological routes for converting inexpensive feedstocks into fermentable media suitable for BC production and highlights the importance of matching substrate type with appropriate processing intensity.

In contrast, agitated cultivation involves continuous movement of the culture medium through shaking or stirring [

93,

94]. Under these conditions, BC forms as irregular particles or spherical pellets dispersed throughout the liquid rather than as a uniform film [

95,

96]. The morphology depends on rotational speed: spherical aggregates typically form above 100 rpm, while irregular forms appear at lower speeds. Agitation enhances oxygen availability, accelerates cellulose synthesis, and generally yields higher productivity compared to static culture [

41,

97]. However, BC obtained from agitated fermentation exhibits lower crystallinity, shorter polymer chains, and reduced mechanical strength [

90,

98]. Moreover, continuous agitation may induce mutations leading to non-cellulose-producing strains, ultimately decreasing yield [

96]. Despite these drawbacks, agitated culture offers advantages for large-scale manufacturing by reducing production time by up to 90%, increasing yield, and simplifying process scalability. Therefore, most commercial BC is produced using agitated fermentation when uniform film morphology is not required [

93].

Crystallinity exerts a significant influence on pore architecture and mechanical stability, demonstrating an inverse relationship: elevated crystallinity corresponds to a reduction in porosity and swelling [

99,

100]. Additives such as calcofluor (CF) and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) modify the morphology of microfibrils, resulting in a reduction in width from 65 nm (untreated) to 32 nm (CMC) and 49 nm (CF), simultaneously decreasing crystallinity from 85% to 71% and 55%, respectively [

101]. Alkaline post-treatment similarly impacts these properties. Films derived from

A. xylinum exhibit tensile strength up to 208 MPa; however, treatment with 10% NaOH induces fibril swelling and fracture, resulting in a decrease in strength to 162 MPa [

102]. Conversely, optimized purification employing 0.01 M NaOH at 70 °C for 2 h maintains structural integrity [

103]. Composite BC materials (such as BC–acrylic acid hydrogels) display pore diameters ranging from 10 to 100 µm and mesh sizes approximately 3 nm [

104]. These hierarchical configurations promote enhanced permeability and stability, thereby extending the applicability of BC to areas such as wound dressings and packaging [

105].

BC demonstrates exceptional thermal and mechanical stability when juxtaposed with traditional petroleum-based plastics [

62]. The tensile strength is observed to range between 18 and 22 MPa, accompanied by a Young’s modulus of 15–18 GPa [

47,

106]. Following wet-drawing and hot-pressing processes, ultrathin BC films (4–10 µm) derived from

G. xylinus achieve a strength of 758 MPa and a toughness of 42 MJ m

−3; twisted fibers attain 954 MPa and 93 MJ m

−3 [

71,

107]. The thermal degradation pathway occurs through dehydration, depolymerization, and glycosidic bond cleavage, with T_dmax ranging from 319 to 374 °C and a minimal weight loss occurring below 100 °C [

104,

108]. Dynamic mechanical analysis indicates that BC sustains a stable storage modulus within the temperature range of −130 °C to 200 °C, in contrast to petroleum-based plastics, which exhibit degradation of modulus as a function of temperature [

109,

110]. These observations reflect intrinsic material properties of BC and do not depend on the use of degraded or spoiled raw materials for fermentation. Rather, BC’s superior stiffness and thermal resilience arise from its highly crystalline nanofibrillar architecture, regardless of whether the carbon source is a refined sugar or a hydrolysate-based substrate.

In addition to its mechanical robustness, BC provides remarkable biocompatibility and environmental sustainability [

111,

112]. It exhibits chemical stability, resistance to ultraviolet light, and thermal durability up to 250 °C [

112]. The absence of lignin and hemicellulose in BC facilitates its chemical functionalization [

113]. Furthermore, the material is non-toxic and elicits a minimal immune response, thereby ensuring safety for biomedical applications [

112]. BC membranes are characterized by transparency and biodegradability in soil within 2 to 9 weeks [

47,

60], presenting a feasible alternative to address microplastic pollution [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. The incorporation of natural antimicrobials (such as chitosan, carvacrol, silver nanoparticles, or plant oils) augments antibacterial efficacy against

E. coli and

S. aureus [

114]. The blending of BC with other biopolymers (e.g., gelatin, alginate, lignin) enhances both mechanical and barrier properties [

113]. In comparison to petroleum-based plastics (such as polyamide, polycarbonate, polyoxymethylene, polypropylene), which soften and deform at approximately 200 °C, BC-based materials maintain structural integrity and biodegrade within roughly 45 days [

60,

72].

6. Applications of BC-Based Food Packaging

Food packaging systems establish controlled microenvironments that mitigate external stressors, thereby delaying food deterioration. This protective role is vital for preserving sensory attributes, nutritional integrity, and microbial safety during shelf life. In this context, BC serves as a versatile biomaterial combining controllable porosity, tunable elasticity, and natural biodegradability, enabling its adaptation to various preservation and barrier requirements. Through targeted functionalization, BC can acquire enhanced mechanical, antimicrobial, or antioxidant properties, broadening its suitability for next-generation sustainable packaging applications [

132]. Importantly, adoption in commodity formats depends on unit economics at scale, where materials must meet cost-per-area targets and run on existing converting lines without productivity loss; therefore, technical performance must be paired with credible manufacturing routes that lower cost relative to incumbent polyethylene and polypropylene [

1,

20,

21,

22].

Beyond laboratory and pilot-scale demonstrations, the transition of BC-based packaging from research to industrial implementation remains constrained by several practical and regulatory challenges. At the industrial level, large-scale fermentation faces high substrate costs, limited reactor oxygen transfer efficiency, and batch-to-batch variability that influence yield and film uniformity. Continuous bioreactor designs and strain engineering are being explored to mitigate these bottlenecks. From a regulatory perspective, BC-based food contact materials must comply with safety frameworks such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration 21 CFR and the European Union Regulation No 1935/2004, which require comprehensive assessment of migration, biodegradability, and potential additives or nanocomposites used for functionalization. The absence of harmonized global standards for bio-based packaging further complicates commercialization. Moreover, industrial adoption depends on cost-competitiveness with petroleum-derived plastics, scalability of purification and drying steps, and compatibility with existing converting and sealing technologies. Addressing these challenges through integrated techno-economic analysis, green manufacturing, and clear regulatory guidance will be pivotal for the widespread deployment of BC-based food packaging systems [

18,

19,

20,

21,

78]. In economic terms, media and nutrients can account for a large share of operating costs, which motivates low-cost feedstocks and process intensification; waste-stream substrates and optimized bioprocess conditions reduce raw-material burden and improve yields, directly improving cost-per-kilogram of BC [

43,

44,

45,

71,

72,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84]. Likewise, energy-intensive purification and drying are significant contributors to cost; process choices that enable continuous production, reduced washing loads, or reel-to-reel dewatering are therefore central to feasibility [

44,

45,

46,

96]. Life-cycle assessments indicate that process electricity and chemical inputs dominate environmental and cost hotspots, so improvements that lower energy and solvent use strengthen both sustainability and competitiveness [

28,

29].

Head-to-head with low-cost plastics, BC will not compete purely as an undifferentiated commodity film; instead, it competes where performance creates value that outweighs material cost. Barrier and mechanical enhancements achieved by chemical functionalization and multilayer constructions improve water-vapor and grease resistance while preserving strength, enabling down-gauging and reduced product loss [

109,

117,

119]. For smart packaging, incremental costs arise from indicators, bioactives, or antimicrobial layers; however, these premiums can be offset when films demonstrably extend shelf life, reduce returns, and cut food waste, which are substantial cost drivers in cold-chain logistics [

1,

19,

22,

29]. Consequently, the relevant metric is total cost of ownership rather than resin price alone; in use cases with high spoilage risk or premium produce, BC-based active or intelligent formats can be economically advantageous even if material unit cost exceeds polyethylene [

1,

19,

20,

21,

22,

28]. Moreover, functional layers can be applied at low coat weights and integrated into standard coating, printing, and lamination workflows, which limits capital expenditure and preserves line speeds [

106,

112,

114].

The suitability of BNC for specific food categories depends primarily on its moisture sensitivity, mechanical stability, and response to freeze–thaw conditions. Products with high spoilage rates and moderate moisture levels, such as berries, leafy greens, and fresh herbs, benefit from BNC’s humidity-regulating properties and its capacity to incorporate antimicrobial or antioxidant agents (

Table 6) [

106]. Dry foods, including cereals and snacks, are also compatible because modified BNC films provide adequate grease and oxygen barriers. In contrast, applications involving frozen foods remain challenging because BNC films undergo structural collapse when subjected to repeated freeze–thaw cycles [

110]. High-liquid foods, such as soups or sauces, require sealing integrity and water resistance beyond the typical performance of unmodified BNC. These distinctions reflect material behavior rather than speculative performance claims and indicate where BNC can be realistically deployed within current technological constraints [

115].

Traditional food packaging primarily serves as static barriers, while contemporary active packaging systems interact dynamically with food, facilitating the regulated release or absorption of compounds that enhance quality during storage [

133,

134,

135,

136,

137,

138,

139,

140]. This advancement transitions packaging from mere containment to active quality preservation, enhancing antibacterial and antioxidant efficacy and enabling real-time freshness monitoring [

134]. However, polysaccharide- and protein-based materials often exhibit limitations in scalability owing to mechanical deficiencies [

136]. Conversely, BC, derived from biosynthesis, features a robust crystalline nanonetwork, making it a viable sustainable reinforcement material [

135]. For instance, the incorporation of BC nanowhiskers significantly improves film strength [

137]. Additionally, BC–citrus pectin/thyme essential oil composites preserve the structural integrity of BC while achieving remarkable tensile strength and superior moisture barrier properties, effectively maintaining grape quality for 9 d through synergistic reinforcement and hydrophobic modifications [

138]. From an implementation perspective, active layers can be metered at grams per square meter using industrially familiar coating or extrusion-lamination steps, which constrains added cost while delivering shelf-life gains that improve retailer margins [

106,

112,

114].

In addition to mechanical strength, packaging materials must also inhibit oxidative spoilage and microbial contamination. Natural antioxidants, including polyphenols and curcumin, are frequently integrated into active films due to their safety and compatibility. Shi et al. created BC–gallic acid composites with notable antioxidant capabilities, significantly extending strawberry shelf life at room temperature due to the phenolic hydroxyl groups in gallic acid that neutralize reactive oxygen species [

34]. Agricultural by-products rich in natural antioxidants can further reduce production expenses and foster circular economy initiatives. For instance, Cazón et al. developed BC/chitosan films containing grape bagasse extract, achieving a high phenolic content and effective radical scavenging, thereby safeguarding food from oxidative deterioration [

60]. Furthermore, the structural engineering of BC-based composites can improve synergistic functionality. Zhang et al. developed multilayer BC/gellan gum/quaternary ammonium chitosan microsphere films that offered water vapor barrier properties and over 90% antibacterial efficacy against

E. coli and

S. aureus. Preservation studies demonstrated that strawberries coated with these multilayer films retained freshness and hydration for up to 5 d [

126]. Economically, using waste-derived phenolic sources and low-add-on multilayers reduces formulation cost, while demonstrated extensions in shelf life create measurable value in high-loss categories such as berries and leafy produce [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

28,

60,

126].

Intelligent packaging systems have emerged as a sophisticated category of materials proficient in visually monitoring the freshness of food items through their responses to variations in pH levels, gaseous emissions, and other environmental stimuli. Anthocyanins, curcumin, alizarin, and betaine represent prominent natural pH-sensitive dyes utilized as indicators of freshness. Anthocyanins undergo notable chromatic transitions from red to blue as pH levels increase, thereby reflecting their structural transformation from the flavylium cation to the quinonoid base. Li et al. [

127] incorporated anthocyanins into bacterial cellulose-based Pickering emulsions stabilized with camellia oil, resulting in packaging films that transitioned from purple-red to brown as the spoilage of shrimp advanced. Similarly, curcumin demonstrates pH-dependent color alterations linked to keto-enol tautomerism, transitioning from yellow to reddish-brown at elevated pH levels. Miao et al. [

128] integrated curcumin into bacterial cellulose to fabricate films that shifted from light to dark yellow as basa fish deteriorated, effectively signaling spoilage and surpassing traditional plastic packaging in efficacy. Furthermore, multicomponent pigment systems have exhibited enhanced sensitivity in comparison to single dye systems. Zhou et al. [

139] embedded a curcumin–anthocyanin composite into bacterial cellulose nanofiber/gelatin films that transitioned from yellow to red across a range of acidity levels, indicating significant potential for practical applications in freshness monitoring. From a cost standpoint, most indicator chemistries are low-mass add-ons printable by flexographic or gravure methods, so the dominant expense is integration into converting rather than pigment cost, which supports economic feasibility when indicators prevent out-of-date write-offs [

1,

19,

21,

127,

128].

Gas-responsive indicator films derived from BC now consistently convey the presence of spoilage gases such as ammonia (NH

3) and hydrogen sulfide (H

2S) through pronounced colorimetric and optical alterations. Colorimetric systems that incorporate transition-metal complexes or metal nanoparticles integrated within BC or BCNC demonstrate swift, perceptible reactions to amines and sulfides at concentrations pertinent to food safety [

140,

141,

142,

143,

144]. For instance, a BC/CMC film that is functionalized with the imidazolium copper complex HIm

2CuCl

4 exhibits a reliable transformation from a stable lime-green to blue upon exposure to ammonia in the parts per million (ppm) range, thereby serving as an effective monitoring tool for fish spoilage [

141]. Furthermore, matrices of BC/BCNC modified with silver or copper nanoparticles also exhibit darkening in response to ammonia and hydrogen sulfide due to redox or electronic transitions of the metallic constituents, while silver nanoparticles embedded in BC nanopaper can be influenced by gaseous ammonia—mechanisms that provide a robust basis for effective visual sensing [

140,

142,

143]. Because sensing layers can be deposited by low-cost printing and slot-die coating at minimal coat weights, the marginal cost per package remains small relative to avoided spoilage and improved quality assurance [

114,

126,

127,

128,

140,

141,

142,

143].

Beyond cinematic productions, edible and functional coatings present significant appeal due to their ability to be applied via spraying or dipping methodologies, thereby ensuring uniform coverage of irregularly shaped food items, regulating gas and moisture exchange, and facilitating the delivery of bioactive compounds. Pickering-emulsion systems, which are stabilized by colloidal biopolymers, permit the controlled release of essential oils that exhibit potent antioxidant and antimicrobial properties; notably, this methodology is seamlessly applicable to coatings reinforced with BC [

144]. The integration of BC nanofibers as nanofillers substantially enhances the mechanical strength of gelatin-based edible coatings and contributes to the preservation of fresh-cut apple quality during storage, all while preserving a high degree of visible transparency for visual assessment [

145]. To achieve anti-adhesion properties and facilitate the easy removal of contents from packaging, superhydrophobic BC-based coatings that are engineered with inorganic waxy phases and silica roughness effectively reduce residue left by viscous food substances (e.g., honey, yogurt). Scalable systems composed of BC nanosilica and beeswax have demonstrated water contact and sliding angles of approximately 153° and 3°, respectively, thereby providing self-cleaning and anti-fouling capabilities that are well-suited for reusable or low-waste packaging formats [

146]. Critically, these coatings are applied at low thickness and can be processed on standard lines, which lowers the incremental cost and eases competition with polyethylene coatings in niche, performance-driven formats [

1,

20,

21,

22,

114,

146].

Hydrogel and aerogel configurations derived from BC expand their applicability from moisture and odor regulation to cushioning and proactive protection. Moisture-absorbing BC–guar-gum hydrogels enhance barrier and mechanical properties for berry packaging while effectively managing headspace humidity [

147]. Pertaining to ethylene regulation, BC hydrogels integrated with microalgae serve as biologically based ethylene scavengers, achieving over 90% removal efficiency, thereby prolonging the shelf life of fruits and vegetables [

148]. Additionally, an innovative active-packaging strategy involves the creation of oxygen-scavenging coatings through the immobilization of enzymes (such as glucose oxidase) or redox agents within cellulosic matrices, a methodology that is compatible with BC substrates [

149]. In the context of pads and liners, BC-reinforced antibacterial aerogels (for instance, CMC@AgNP/BC/citric-acid) synergistically combine rapid exudate absorption with robust antimicrobial properties, significantly reducing bacterial load and color degradation of chilled meats over a seven-day period [

150]. Ultimately, foam-templated porous BC films and aerogels provide adjustable pore size and thickness under ambient conditions and can be subsequently functionalized (for example, with chitosan) to enhance liquid absorption and antibacterial efficacy while preserving low density and cushioning capabilities [

151,

152]. Because pads, liners, and inserts are used at very low mass per pack, these formats are among the earliest economically feasible BC applications, where performance benefits justify modest material premiums [

21,

22,

23,

28,

150,

151,

152].

Material cost remains one of the main constraints for the wider deployment of BNC-based food packaging and is strongly shaped by process conditions rather than chemistry alone [

97,

110]. Pilot- and industrial-scale studies show that expenses associated with carbon sources, fermentation time, and downstream operations such as purification and drying significantly elevate the production cost of BNC compared with commodity thermoplastics [

96,

97,

98,

99]. Nevertheless, several works demonstrate that using organic residues and low-value side streams as feedstocks, together with in situ composite formation, can lower medium costs and improve space–time yields, which directly reduces the effective cost per kilogram of BNC [

41,

114,

115,

116,

117,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123,

124,

125,

126,

127]. Advanced structuring strategies, including force-induced alignment, nacre-inspired architectures, and multilayer films, achieve mechanical and barrier properties that are competitive with or superior to conventional plastics, allowing thinner gauges or multifunctional formats that can partially offset higher material prices in demanding applications [

98,

106,

108,

114,

119]. Overall, current evidence indicates that BNC occupies a higher-cost regime than polyethylene and polypropylene and is therefore best suited for packaging formats where performance gains, added functionality, or sustainability drivers can justify a higher material price (

Table 7).

Overall, the economic feasibility of BC-based and smart packaging improves when processes exploit low-cost feedstocks, continuous or intensified operations, and thin functional layers integrated on incumbent equipment [

43,

44,

45,

71,

72,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

95,

106,

112,

114]. Competition with polyethylene is realistic in segments where waste reduction, product quality, brand sustainability claims, or regulatory drivers provide measurable value that offsets higher material cost [

1,

19,

20,

21,

22,

27,

28,

106,

112,

114]. Consequently, BC is best positioned for high-value produce, protein, and premium ready-to-eat categories, as well as function-specific components such as pads, labels, and intelligent indicators that leverage minimal coat weight with maximum effect [

150,

151,

152,

153].

7. Challenges and Future Work

Despite remarkable progress in developing BC-based bioplastics for food packaging, several persistent challenges continue to limit their industrial scalability, environmental resilience, and cost efficiency [

60]. Despite its advantageous optical clarity, structural cohesion, and capacity for biological decomposition relative to other biopolymers, its transition from laboratory production to commercial implementation remains hindered by both technological and regulatory constraints. Recent advances have improved BC performance through functionalization and structural tuning [

97,

110], yet these improvements have not fully addressed the systemic barriers associated with scale-up, cost, and long-term stability.

One of the central obstacles involves the modification of BC with exogenous additives such as nanomaterials, carbon-based compounds, and plasticizers that enhance its strength, flexibility, or barrier properties. While these modifications improve functional performance, their long-term environmental and health impacts remain uncertain [

77]. The potential migration of nanoparticles or plasticizers into food products poses biosafety risks, highlighting the urgent need for internationally harmonized standards and regulations. Evidence from active and intelligent packaging research demonstrates that certain nanoparticles, essential oils, and responsive dyes exhibit concentration-dependent migration behavior [

133,

134,

135,

136,

137,

138,

139,

140,

141,

142,

143], reinforcing the necessity for standardized toxicological and migration testing (e.g., EFSA, FDA). Future studies should focus on defining safe concentration limits for additives, conducting systematic toxicological assessments, and performing full life-cycle analyses to ensure environmental compliance and consumer safety.

From an economic standpoint, BC production remains costly due to the price of conventional culture media and the length of the fermentation process [

127]. Achieving large-scale feasibility requires optimization of both substrates and process conditions, including the selection of well-defined biomass feedstocks for fermentation. The substitution of refined carbon sources with agricultural or industrial residues such as fruit waste, molasses, or crude glycerol, that is, lignocellulosic and carbohydrate-rich biomass streams that serve as low-cost carbon sources for BC-producing strains, can significantly reduce production costs while promoting sustainability. Additionally, the adoption of open or semi-continuous fermentation systems could minimize energy consumption and shorten production time. Advances in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology may further improve cellulose biosynthesis by redirecting metabolic fluxes and enhancing substrate utilization efficiency. Directed evolution and strain optimization approaches have recently proven effective in increasing productivity and modifying fibril architecture [

122], offering promising tools for cost reduction.

Another limitation concerns the relatively rapid biodegradation of BC under natural environmental conditions. The high density of hydroxyl groups promotes enzymatic hydrolysis and leads to complete degradation within roughly six months [

150]. Although this property supports ecological sustainability, it compromises the structural stability required for packaging high-moisture foods including dairy, fresh produce, and chilled meats, and it becomes even more critical for frozen products, where ice-crystal formation and freeze–thaw cycles can induce irreversible structural collapse of BNC films. Freeze–thaw instability has been consistently reported in studies evaluating cold-chain conditions, indicating that BNC cannot maintain dimensional or mechanical integrity during frozen storage [

106]. Achieving equilibrium between environmental degradability and mechanical durability is therefore essential for applications spanning chilled and frozen food packaging. Techniques such as mild cross-linking with biocompatible agents, surface hydrophobization, or the design of multilayered composites could extend the material’s functional lifespan without compromising its eco-friendly profile.

In addition, the limited flexibility, ductility, and puncture resistance of BC restrict its use in demanding packaging applications [

107]. These issues can be mitigated by bioinspired structural design that imitates natural composites, by incorporating flexible matrices such as gelatin, polycaprolactone, or thermoplastic starch, and by controlling fibril alignment during biosynthesis to achieve desired mechanical orientation. The inclusion of reinforcing nanofillers such as lignin, cellulose nanocrystals, or graphene oxide may further enhance strength while preserving biodegradability and transparency. Emerging approaches such as nacre-inspired hybrid films, ultrathin BC layers, and mica-reinforced nanostructures have demonstrated substantial gains in tensile strength and dimensional stability [

106,

107,

109,

119], highlighting the importance of hierarchical design strategies.

Current research on BC packaging remains concentrated on perishable items such as fruits, vegetables, and meat. Broader exploration of its suitability for processed, frozen, and ready-to-eat products could expand its commercial reach. Future innovations should also focus on the integration of smart functions including pH indicators, spoilage sensors, and digital tags to create intelligent BC-based packaging capable of real-time monitoring and traceability throughout the food supply chain.

In addition to technological and economic considerations, future progress critically depends on the establishment of standardized shelf-life testing protocols for BC-based composites. Presently, most reported performance data are derived from small-scale laboratory trials under controlled conditions, which often fail to replicate the complexity of real food matrices. Large-scale, controlled studies involving perishable commodities such as meat, cheese, and fresh produce are essential to accurately assess barrier stability and microbial resistance under realistic storage and handling environments. Such studies should quantitatively evaluate parameters including oxygen transmission rate, water vapor transmission rate, and microbial spoilage kinetics relative to benchmark petroleum-based plastics. Harmonized methodologies will enable meaningful cross-comparison of results, support regulatory acceptance, and provide industry with reliable indicators of performance and shelf-life extension potential.

Moreover, given the incorporation of novel nanomaterials, cross-linkers, and plasticizers in BC functionalization, regulatory evaluation must accompany technical development. The current and anticipated regulatory frameworks established by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Food Safety Authority categorize many nanomaterial- and plasticizer-based additives as food-contact substances that require migration, toxicological, and environmental assessments prior to approval. Additives such as silver nanoparticles, polyethylene glycol, citric acid, and polycaprolactone exhibit varying authorization statuses depending on concentration and intended use, underscoring the need for continuous alignment between formulation strategies and evolving safety standards. Clear documentation of compliance pathways and harmonized global guidelines will be critical for ensuring consumer safety, facilitating market entry, and accelerating the industrial translation of BC-based food packaging systems.

Ultimately, the advancement of BC-based packaging requires a multidisciplinary approach that combines material science, biotechnology, and circular-economy principles. Priority should be given to the development of scalable fermentation systems, cost-effective medium formulations, and verified biosafety protocols. When coupled with intelligent sensing technologies and optimized mechanical design, BC has the potential to evolve from a research material into a practical and sustainable alternative to petroleum-based plastics for modern food packaging applications. Although this review provides a comprehensive overview of the progress and prospects of bacterial cellulose–based food packaging, it has several inherent limitations. The discussion relies primarily on peer-reviewed literature available in English and does not encompass patent data or unpublished industrial reports that could further clarify large-scale implementation trends. Quantitative comparison of production yields, economic costs, and environmental impacts across different studies remains challenging because of variability in experimental designs and reporting standards. Therefore, future systematic meta-analyses and techno-economic assessments are needed to complement this review and strengthen the evidence base for industrial translation.