Functionalization of PET Track-Etched Membranes by UV-Induced Graft (co)Polymerization for Detection of Heavy Metal Ions in Water

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Instruments

2.2. Preparation of the Membranes and Their Modification

2.3. Membrane Characterization

2.4. Anodic Stripping Voltammetry Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

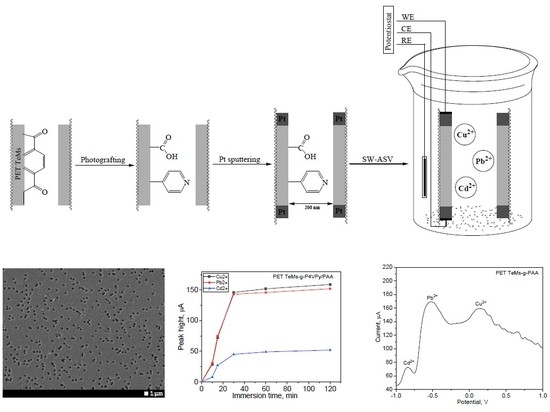

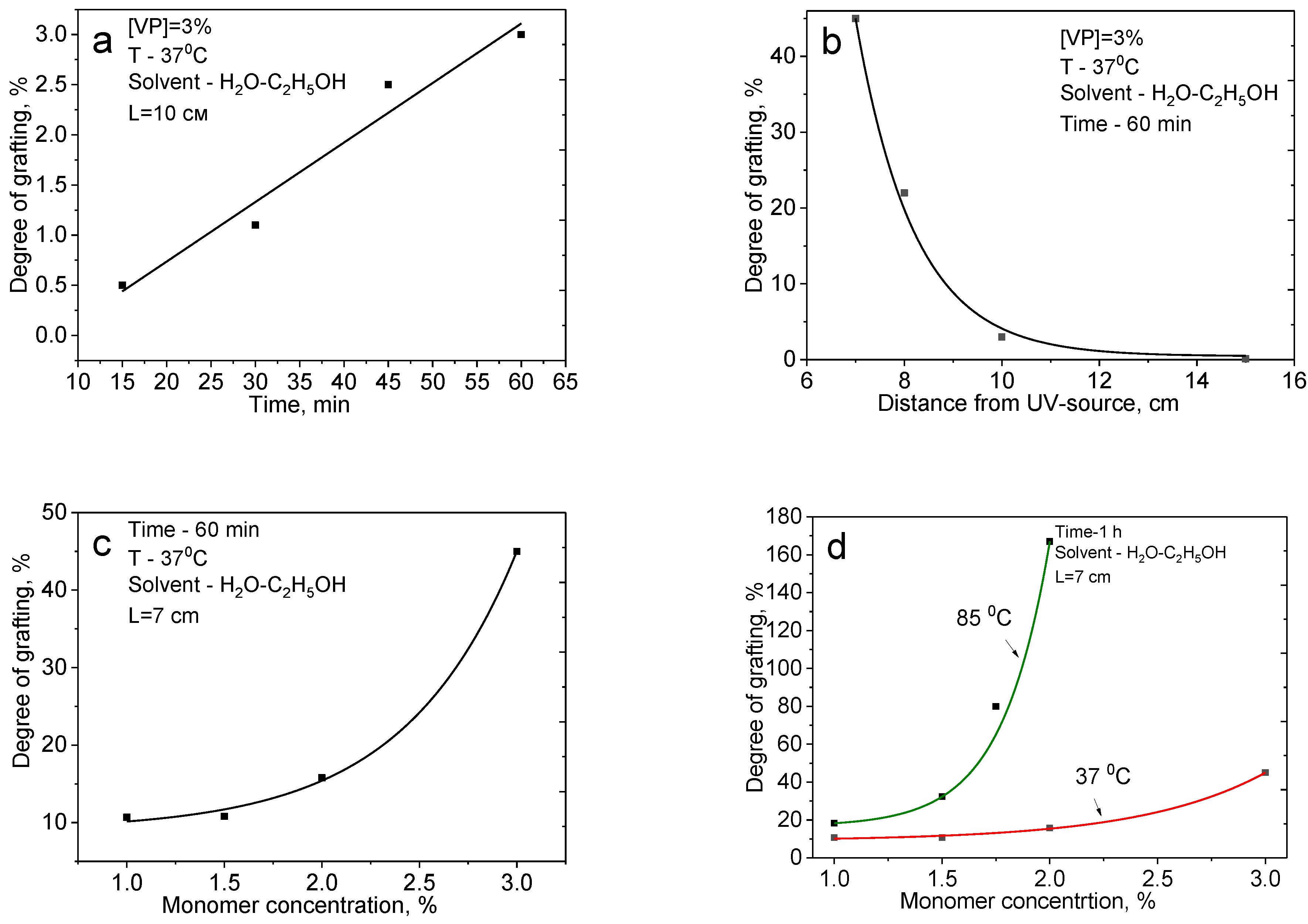

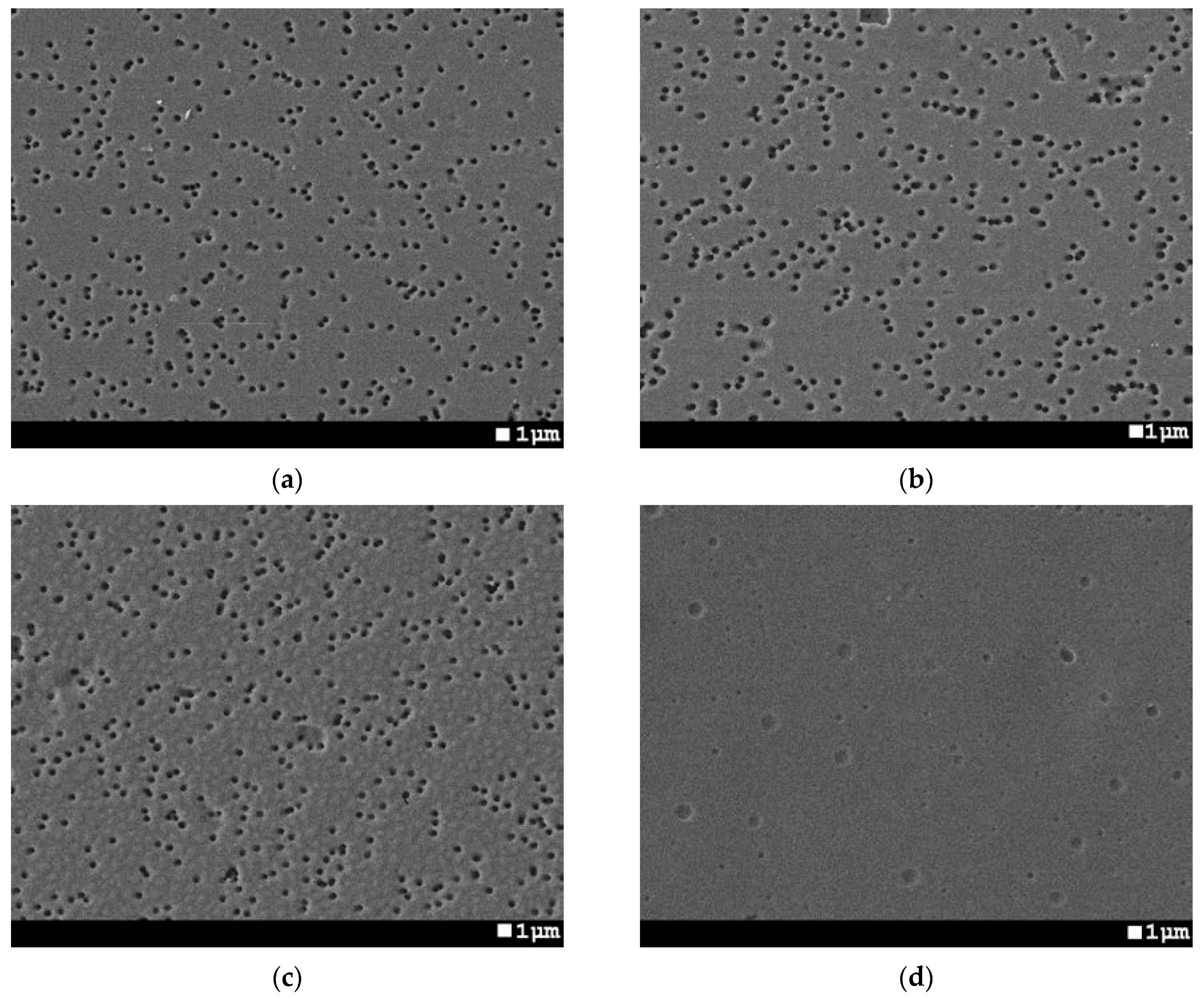

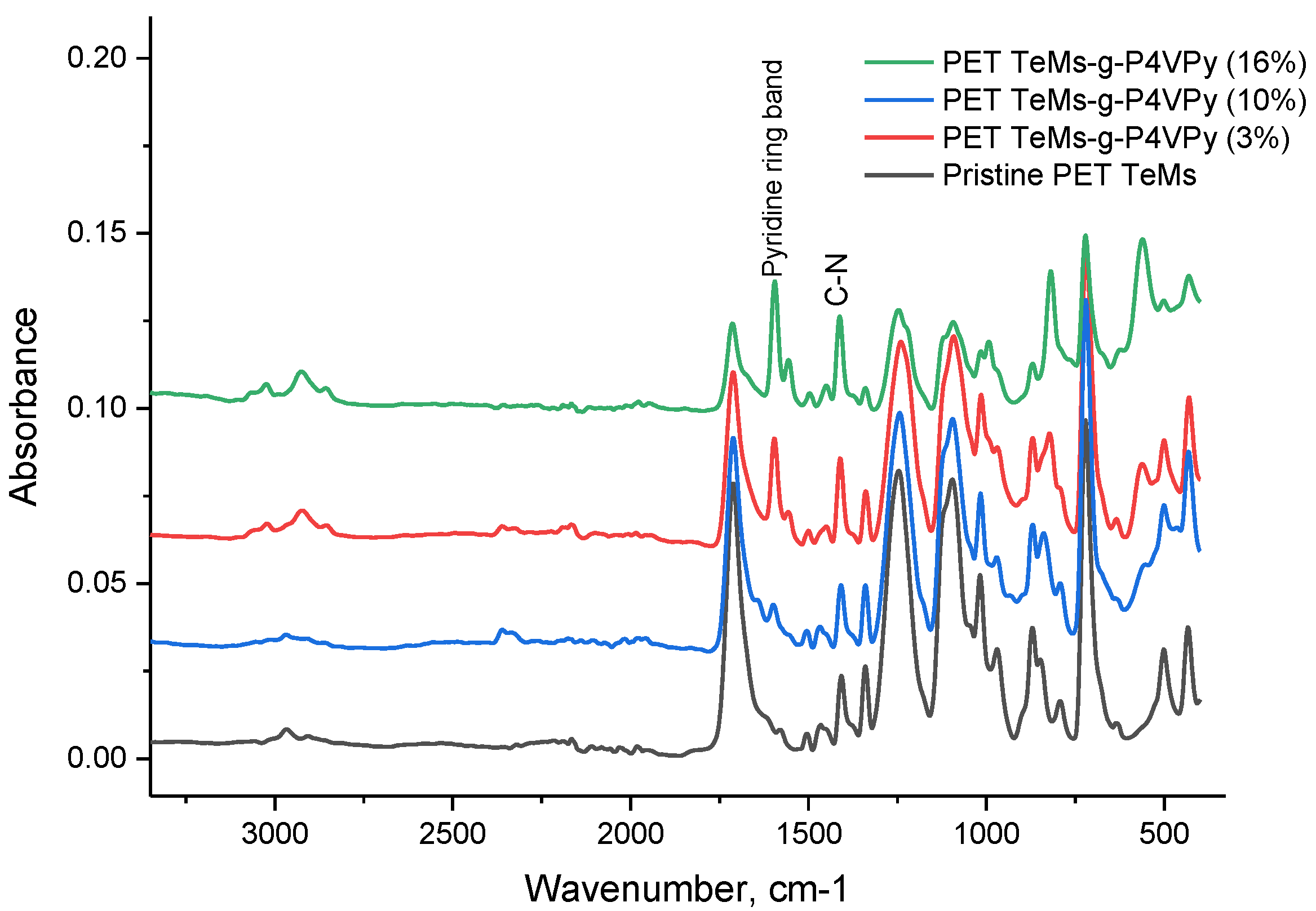

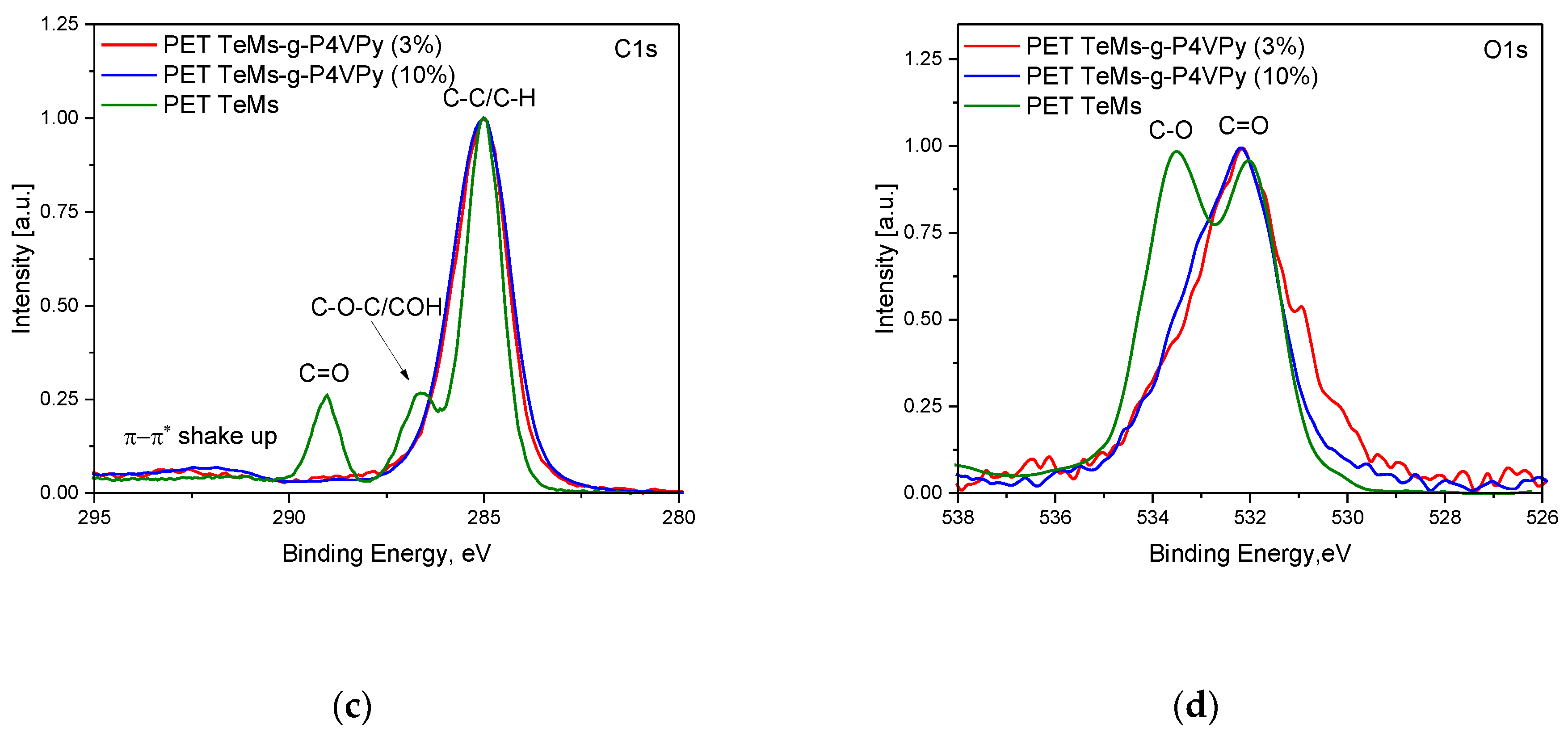

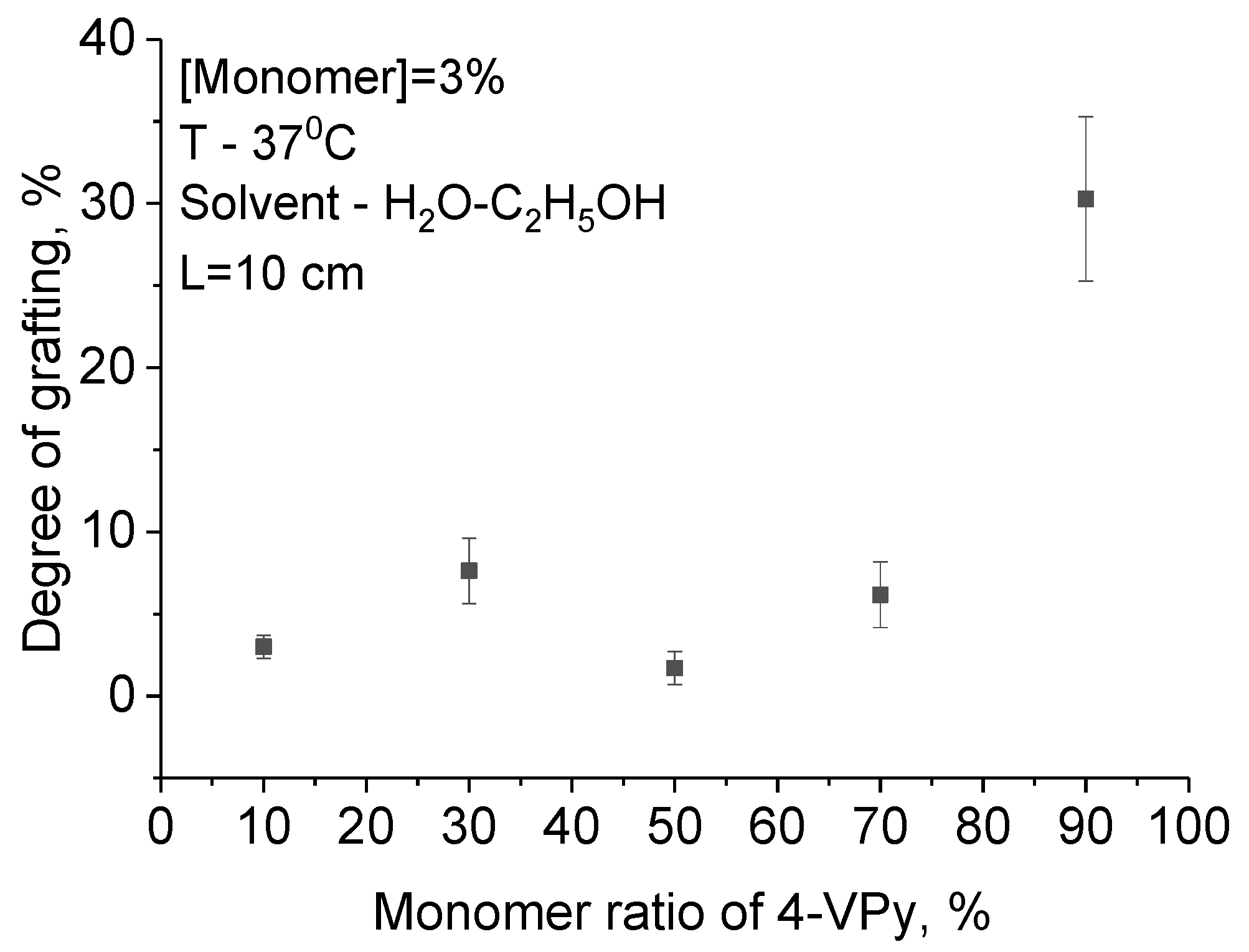

3.1. UV-Induced Graft Polymerization of 4-vinylpyridine on PET TeMs

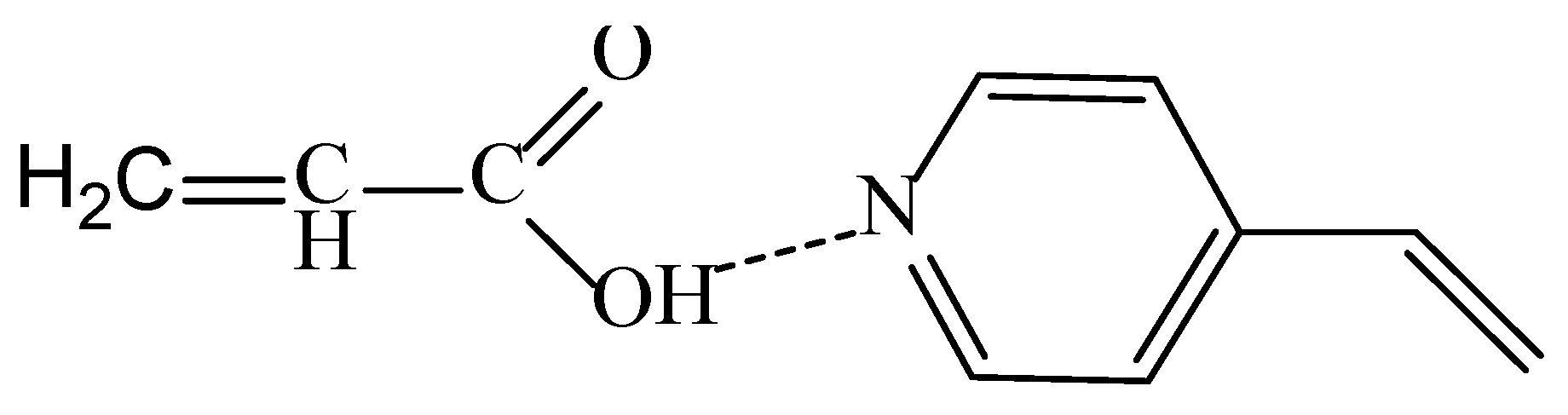

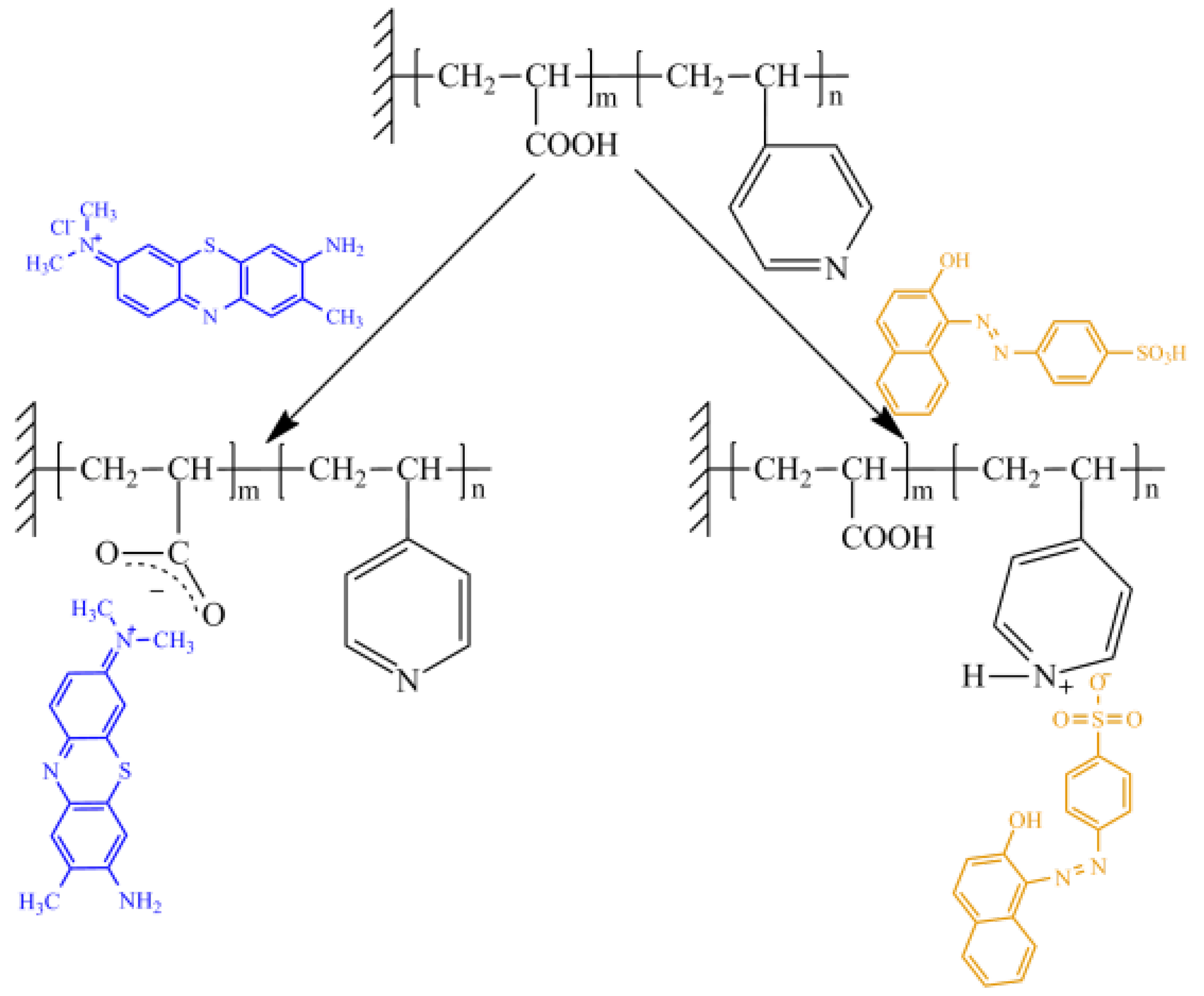

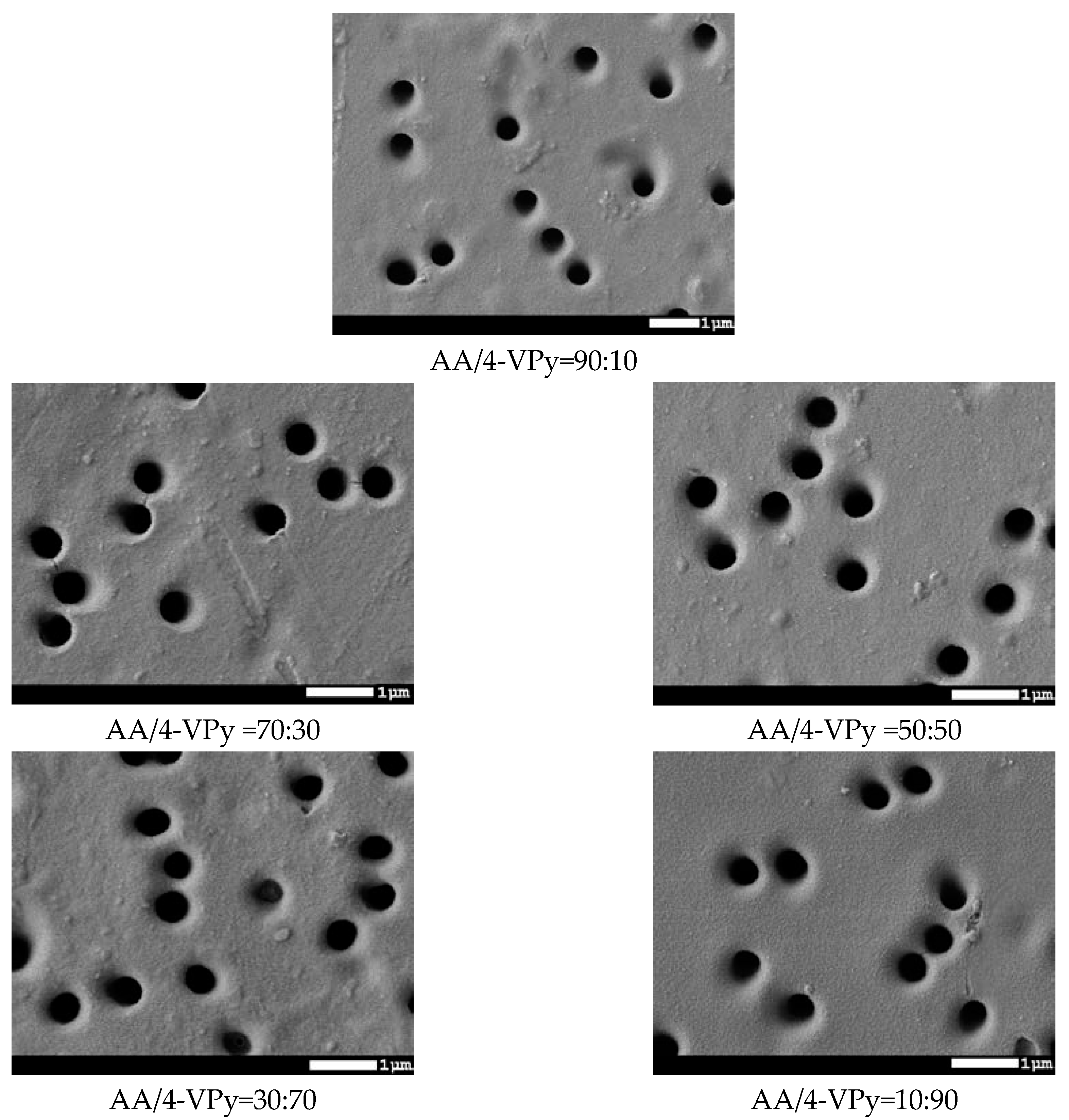

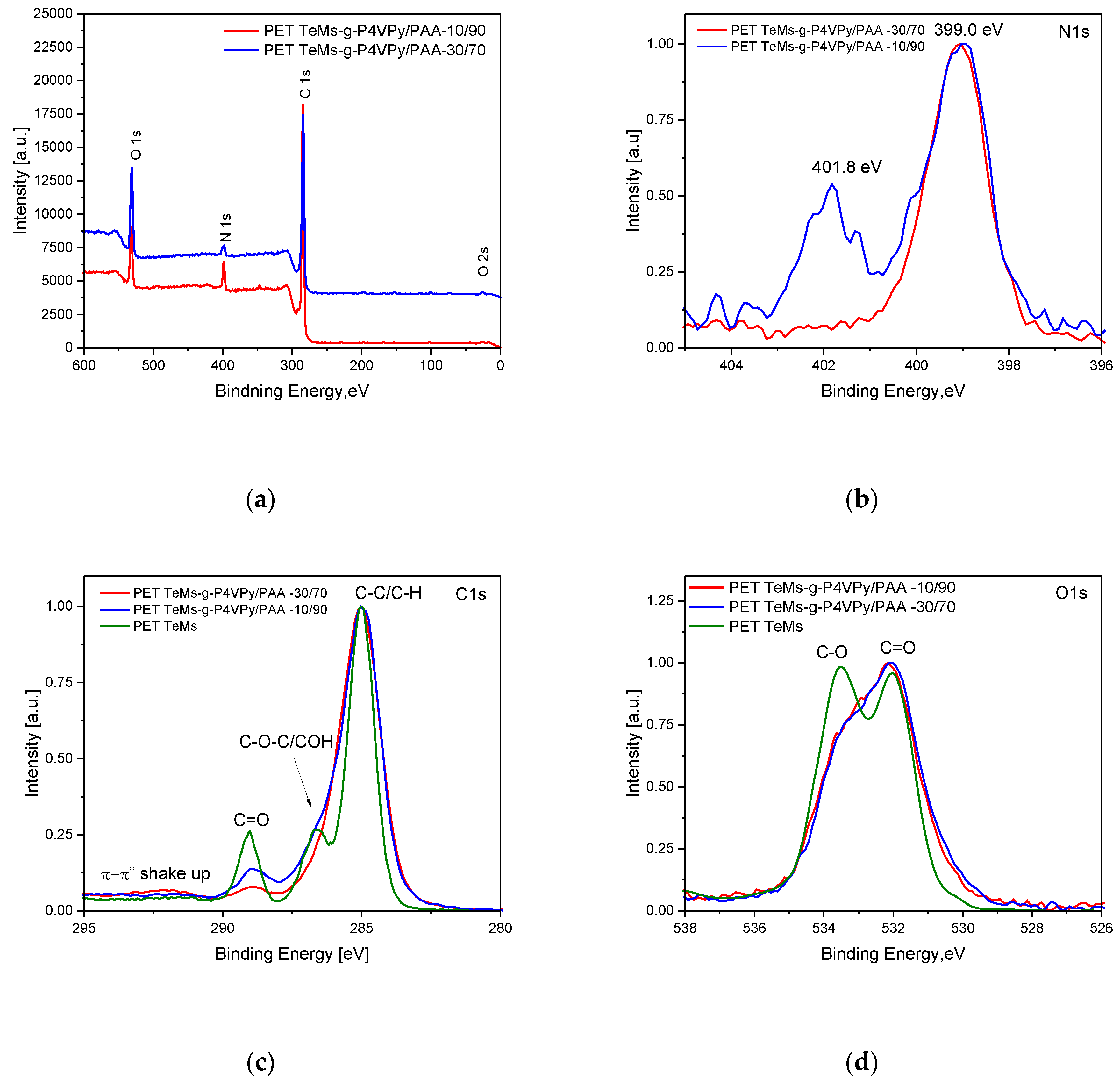

3.2. UV-Induced Graft Copolymerization of 4-Vinylpyridine and Acrylic Acid on PET TeMs

3.3. Electrochemical Detection

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, P.; Kim, K.H.; Bansal, V.; Lazarides, T.; Kumar, N. Progress in the sensing techniques for heavy metal ions using nanomaterials. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 54, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Wu, J.; Ju, H. Electrochemical sensing of heavy metal ions with inorganic, organic and bio-materials. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 63, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 383–385. ISBN 9789241548151.

- Pierce, D.T.; Zhao, J.X. Trace Analysis with Nanomaterials; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2015; p. 418. ISBN 978352763. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X.; Wu, S.; Li, S. Progress on electrochemical sensors for the determination of heavy metal ions from contaminated water. J. Chin. Adv. Mater. Soc. 2018, 6, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liang, X.; Niyungeko, C.; Zhou, J.; Xu, J.; Tian, G. A review of the identification and detection of heavy metal ions in the environment by voltammetry. Talanta 2018, 178, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulla, M.; Ali, A.; Jamal, R.; Bakri, T.; Wu, W.; Abdiryim, T. Electrochemical sensor of double-thiol linked PProDOT@Si composite for simultaneous detection of Cd(II), Pb(II), and Hg(II). Polymers 2019, 11, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, C.M.A.; Brett, A.M.O. Electrochemistry: Principles, Methods, and Applications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993; p. 464. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Chen, T.; Liu, X.; Ma, H. Ultrasensitive and simultaneous detection of heavy metal ions based on three-dimensional graphene-carbon nanotubes hybrid electrode materials. Anal. Chim. Acta 2014, 852, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Yu, X.-Y.; Xu, R.-X.; Liu, J.-H.; Huang, X.-J. AlOOH-Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites: One-Pot Hydrothermal Synthesis and Their Enhanced Electrochemical Activity for Heavy Metal Ions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 4672–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yao, Y.; Ying, Y.; Ping, J. Recent advances in nanomaterial-enabled screen-printed electrochemical sensors for heavy metal detection. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 115, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Ge, P.-Y.; Xu, J.-J.; Chen, H.-Y. Catalytic Deposition of Pb on Regenerated Gold Nanofilm Surface and Its Application in Selective Determination of Pb 2+. Langmuir 2007, 23, 8597–8601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, R.; Bragg, S.A.; Chambers, J.Q.; Xue, Z.-L. Flower-like self-assembly of gold nanoparticles for highly sensitive electrochemical detection of chromium(VI). Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 722, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Kanhere, E.; Miao, J.; Triantafyllou, M.S. Nanoparticles-modified chemical sensor fabricated on a flexible polymer substrate for cadmium(II) detection. Polymers 2018, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia-Caridade, C.; Brett, C.M.A. Strategies, Development and Applications of Polymer-Modified Electrodes for Stripping Analysis. Curr. Anal. Chem. 2008, 4, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Amemiya, S. Stripping Analysis of Nanomolar Perchlorate in Drinking Water with a Voltammetric Ion-Selective Electrode Based on Thin-Layer Liquid Membrane. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 6056–6065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, N.S.; Amr, A.E.-G.E.; El-Tantawy, A.S.M.; Al-Omar, M.A.; Kamel, A.H.; Khalifa, N.M. Tailor-Made Specific Recognition of Cyromazine Pesticide Integrated in a Potentiometric Strip Cell for Environmental and Food Analysis. Polymers 2019, 11, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinaeva, U.; Dietz, T.C.; Al Sheikhly, M.; Balanzat, E.; Castellino, M.; Wade, T.L.; Clochard, M.C. Bis[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl] phosphate radiografted into track-etched PVDF for uranium (VI) determination by means of cathodic stripping voltammetry. React. Funct. Polym. 2019, 142, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessbousse, H.; Zran, N.; Fauléau, J.; Godin, B.; Lemée, V.; Wade, T.; Clochard, M.-C. Poly(4-vinyl pyridine) radiografted PVDF track etched membranes as sensors for monitoring trace mercury in water. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2016, 118, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsbay, M.; Güven, O.; Bessbousse, H.; Wade, T.L.; Beuneu, F.; Clochard, M.-C. Nanopore size tuning of polymeric membranes using the RAFT-mediated radical polymerization. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 445, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessbousse, H.; Nandhakumar, I.; Decker, M.; Barsbay, M.; Cuscito, O.; Lairez, D.; Clochard, M.-C.; Wade, T.L. Functionalized nanoporous track-etched β-PVDF membrane electrodes for lead(ii) determination by square wave anodic stripping voltammetry. Anal. Methods 2011, 3, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuguchi, H.; Shibuya, K.; Fuse, A.; Hamada, T.; Iiyama, M.; Tachibana, K.; Nishina, T.; Shida, J. A dual-electrode flow sensor fabricated using track-etched microporous membranes. Talanta 2012, 96, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuguchi, H.; Sakurai, J.; Kinoshita, Y.; Iiyama, M.; Kijima, T.; Tachibana, K.; Nishina, T.; Shida, J. Flow-based Biosensing System for Glucose Fabricated by Using Track-etched Microporous Membrane Electrodes. Chem. Lett. 2013, 42, 1317–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, P.Y.; Blonskaya, I.V.; Dmitriev, S.N.; Orelovich, O.L.; Sartowska, B.A. Ion track symmetric and asymmetric nanopores in polyethylene terephthalate foils for versatile applications. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms 2015, 365, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, P.Y. Fabrication of functional micro- and nanoporous materials from polymers modified by swift heavy ions. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2019, 159, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinaeva, U.; Lairez, D.; Oral, O.; Faber, A.; Clochard, M.-C.; Wade, T.L.; Moreau, P.; Ghestem, J.-P.; Vivier, M.; Ammor, S.; et al. Early Warning Sensors for Monitoring Mercury in Water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 376, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, S.; Cluley, A.; Mercado, C.; Mueller, A. Imprinted polymers for the removal of heavy metal ions from water. Water Sci. Technol. 2011, 64, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Huang, X.; Tang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Niu, F.; Wang, X. Polymer-based nanocomposites for heavy metal ions removal from aqueous solution: A review. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 3562–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Vallin, J.R.; Sahoo, J.K.; Gao, F.; Boudouris, B.W.; Webber, M.J.; Phillip, W.A. High-Affinity Detection and Capture of Heavy Metal Contaminants using Block Polymer Composite Membranes. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018, 4, 1697–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyagi, M.O.; Onyatta, J.O.; Kamau, G.N.; Guto, P.M. Validation of the polyacrylic acid/glassy carbon differential pulse anodic stripping voltammetric sensor for simultaneous analysis of lead(II), cadmium(II) and cobalt(II) ions. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2016, 11, 3852–3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.L.W.; Ab Ghani, S. Poly(4-vinylpyridine-co-aniline)-modified electrode—Synthesis, characterization, and application as cadmium(II) ion sensor. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2013, 17, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanov, N.M.; Kozhevnikova, N.A.; Kokorin, A.I.; Rogacheva, V.B.; Zezin, A.B.; Kabanov, V.A. Study of the structure of a polyacrylic acid-Cu (II)-poly-4-vinylpyridine ternary polymeric metal complex. Polym. Sci. U.S.S.R. 1979, 21, 2090–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turmanova, S.; Vassilev, K.; Boneva, S. Preparation, structure and properties of metal-copolymer complexes of poly-4-vinylpyridine radiation-grafted onto polymer films. React. Funct. Polym. 2008, 68, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, M. Transport in Membranes. In Basic Principles of Membrane Technology; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996; pp. 210–279. [Google Scholar]

- Korolkov, I.V.; Mashentseva, A.A.; Güven, O.; Gorin, Y.G.; Zdorovets, M.V. Protein fouling of modified microporous PET track-etched membranes. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2018, 151, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolkov, I.V.; Mashentseva, A.A.; Güven, O.; Zdorovets, M.V. Modification of Track-Etched PET Membranes by Graft Copolymerization of Acrylic Acid and N-Vinylimidazole. Pet. Chem. 2017, 57, 1233–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, B.; Hay, J. The thermal degradation of PET and analogous polyesters measured by thermal analysis–Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Polymer 2002, 43, 1835–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Goh, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Tan, K.L. XPS and FTi.r. studies of interactions in poly(carboxylic acid)/poly(vinylpyridine) complexes. Polymer 1998, 39, 3631–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, K.; Trainor, G.T.; Costigan, M.J. Complexation and rate of polymerization of acrylic acid and methacrylic acid in the presence of poly(4-vinylpyridine) in dilute methanol solution. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Chem. Ed. 1984, 22, 2479–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, A.; Borcherding, H.; Jaeger, C.; Hatami, S.; Würth, C.; Hoffmann, A.; Hoffmann, K.; Thiele, T.; Schedler, U.; Resch-Genger, U. Scope and Limitations of Surface Functional Group Quantification Methods: Exploratory Study with Poly(acrylic acid)-Grafted Micro- and Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8268–8276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, S.; Minagawa, K.; Tsuda, M.; Tanaka, M. Spontaneous copolymerization of acrylic acid with 4-vinylpyridine and microscopic acid dissociation of the alternating copolymer. Eur. Polym. J. 2001, 37, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulay, S.; Bensacia, N. Removal of heavy metals by homolytically functionalized poly(acrylic acid) with hydroquinone. Int. J. Ind. Chem. 2016, 7, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biswas, T.K.; Yusoff, M.M.; Sarjadi, M.S.; Arshad, S.E.; Musta, B.; Rahman, M.L. Ion-imprinted polymer for selective separation of cobalt, cadmium and lead ions from aqueous media. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| № Sample | Time of Grafting, min | Concentration of Monomer,% | Distance from UV-Lamp, cm | Temperature, °C | Grafting Degree, % | Effective Pore Size, nm | Pore Size (from SEM Analysis), nm | Porosity, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | - | - | - | - | 400 ± 5 | 405 ± 25 | 22 |

| 2 | 15 | 3 | 10 | 37 | 0.5 | 355 ± 4 | 365 ± 17 | 17 |

| 3 | 30 | 3 | 10 | 37 | 1 | 350 ± 6 | 361 ± 15 | 16.5 |

| 4 | 60 | 3 | 10 | 37 | 3 | 230 ± 6 | 253 ± 22 | 7 |

| 5 | 60 | 3 | 7 | 37 | 45 | 0 | 0 | - |

| 6 | 60 | 3 | 15 | 37 | 0.1 | 357 ± 6 | 376 ± 22 | 17 |

| 7 | 60 | 1 | 7 | 37 | 10 | 145 ± 4 | 167 ± 21 | 4 |

| 8 | 60 | 1.5 | 7 | 37 | 11 | 154 ± 6 | 176 ± 15 | 4 |

| 9 | 60 | 2 | 7 | 37 | 16 | 110 ± 5 | 103 ± 12 | 2 |

| 10 | 60 | 3 | 7 | 37 | 45 | 0 | 0 | - |

| 11 | 60 | 1 | 7 | 85 | 18 | 0 | 0 | - |

| 12 | 60 | 1.5 | 7 | 85 | 32 | 0 | 0 | - |

| 13 | 60 | 2 | 7 | 85 | 167 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Monomer Mixture Composition | Dye Concentration, µM/g | Composition of Grafted Copolymer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [AA] | [4-VPy] | TB | AO | m1 | m2 |

| 90 | 10 | 11.9 | 11.1 | 51.7 | 48.3 |

| 70 | 30 | 21.4 | 89.5 | 19.3 | 80.7 |

| 50 | 50 | 26.6 | 72.1 | 27.0 | 73.0 |

| 30 | 70 | 25.7 | 81.9 | 23.9 | 76.1 |

| 10 | 90 | 34.0 | 44.4 | 43.4 | 56.6 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zdorovets, M.V.; Korolkov, I.V.; Yeszhanov, A.B.; Gorin, Y.G. Functionalization of PET Track-Etched Membranes by UV-Induced Graft (co)Polymerization for Detection of Heavy Metal Ions in Water. Polymers 2019, 11, 1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11111876

Zdorovets MV, Korolkov IV, Yeszhanov AB, Gorin YG. Functionalization of PET Track-Etched Membranes by UV-Induced Graft (co)Polymerization for Detection of Heavy Metal Ions in Water. Polymers. 2019; 11(11):1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11111876

Chicago/Turabian StyleZdorovets, Maxim V., Ilya V. Korolkov, Arman B. Yeszhanov, and Yevgeniy G. Gorin. 2019. "Functionalization of PET Track-Etched Membranes by UV-Induced Graft (co)Polymerization for Detection of Heavy Metal Ions in Water" Polymers 11, no. 11: 1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11111876