Small Nucleolar RNAs as Emerging Players in Cancer Biology and Precision Medicine

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Dysregulation of snoRNAs in Cancer

2.1. Oncogenic snoRNAs

2.2. Tumor Suppressor snoRNAs

2.3. Context-Dependent Functional Plasticity

| snoRNA | Type | Function | Cancer Type | Primary Mechanism | Validation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNORA21 | H/ACA | Oncogene | Colorectal | Hippo/Wnt pathways | In vitro/in vivo | [13] |

| SNORD78 | C/D | Oncogene | Colorectal | Oncoribosome formation | Patient samples | [13] |

| SNORA47 | H/ACA | Oncogene | Breast | EBF3/RPL11/c-Myc axis | Xenografts | [18] |

| SNORA24 | H/ACA | Tumor suppressor | HCC | Translational fidelity | RAS model | [11] |

| SNORD44 | C/D | Tumor suppressor | Colorectal | p53 pathway | Oncolytic virus | [20] |

| SNORD113-1 | C/D | Tumor suppressor | HCC | MAPK/STAT3 inhibition | In vitro/in vivo | [21] |

| SNORA13 | H/ACA | Tumor suppressor | Multiple | Senescence via RPL23/p53 | Cell models | [31] |

| SNORD50A/B | C/D | Context-dependent | Multiple | K-Ras/TRIM21 | Xenografts | [22,23,24] |

| SNORD76 | C/D | Context-dependent | HCC/Glioblastoma | Wnt/Cell cycle | Patient tissues | [25,27,28] |

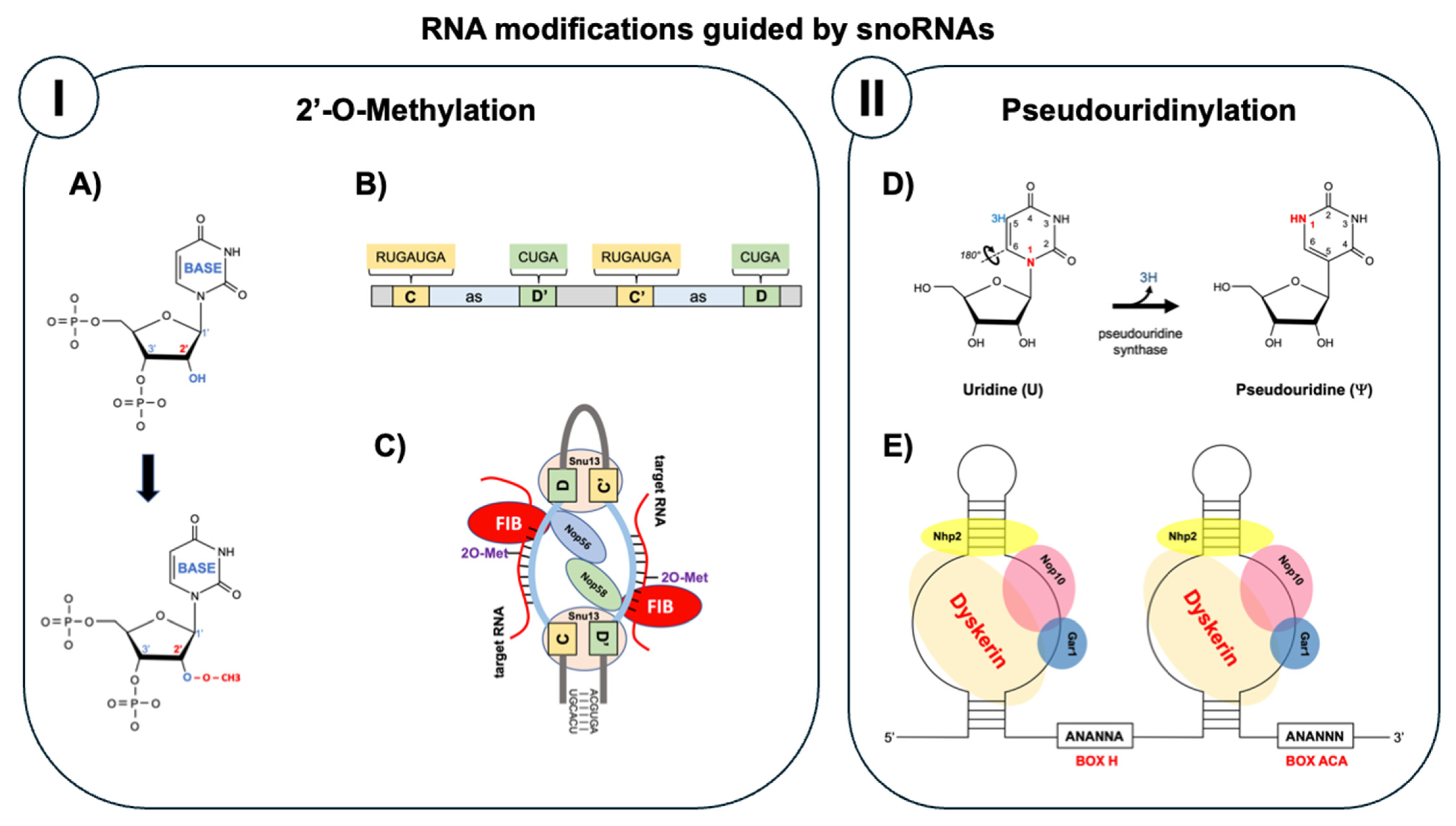

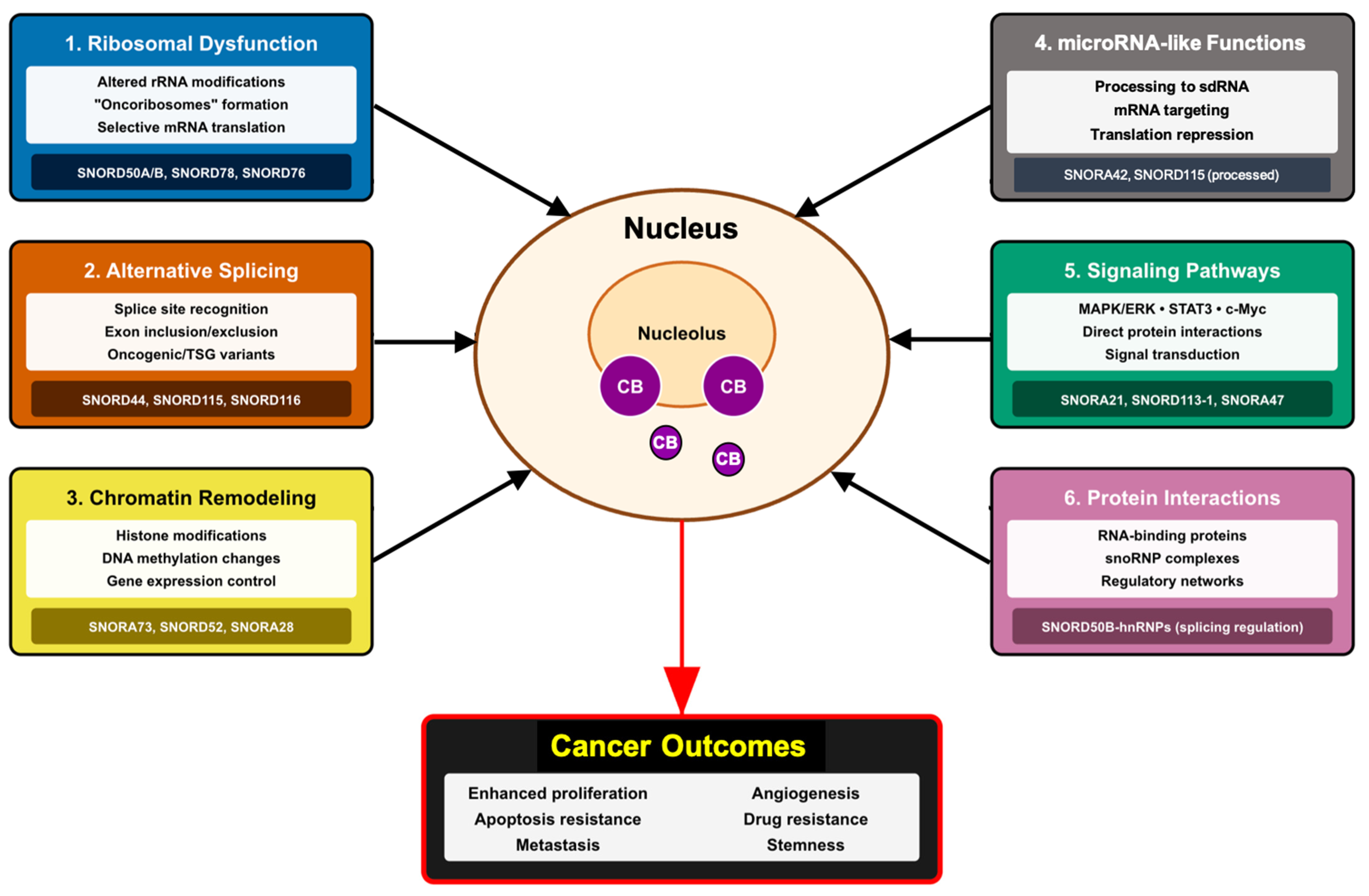

3. Molecular Mechanisms of snoRNA-Mediated Effects in Cancer

3.1. Ribosomal Dysfunction and Translational Control

3.2. Alternative Splicing Regulation

3.3. Chromatin Remodeling and Epigenetic Regulation

3.4. MicroRNA-like Functions

3.5. Integration with Signaling Networks

3.6. snoRNA–Protein Interactions and Regulatory Complexes

4. snoRNAs as Cancer Biomarkers

4.1. Diagnostic Applications

| Cancer Type | snoRNA Panel | Sample Type | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | SNORD16, SNORA73B, SCARNA4, SNORD49B | Plasma | 66.5% | 74.4% | N/A | [58] |

| Lung | SNORD78, SNORD37 | Serum exosomes | N/A | N/A | 0.85 | [59] |

| Colorectal | SNORA51 | Fecal | 82% | 89% | 0.91 | [60] |

| Renal cell | SNORD15A, SNORD35B, SNORD60 | Urine sediment | 78% | 85% | 0.88 | [61] |

| HCC | 9-snoRNA signature | Tissue | N/A | N/A | 0.92 | [64] |

4.2. Prognostic Value and Disease Monitoring

5. snoRNAs as Therapeutic Targets

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAV | Adeno-associated virus |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| ASO | Antisense oligonucleotide |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| cfRNA | Cell-free RNA |

| CLL | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| CTC | Circulating tumor cell |

| DKC1 | Dyskerin |

| EMT | Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| FBL | Fibrillarin |

| FIT | Fecal immunochemical test |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| IGHV | Immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| LNA | Locked nucleic acid |

| MM | Multiple myeloma |

| ncRNA | Non-coding RNA |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| RNP | Ribonucleoprotein |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| sdRNA | snoRNA-derived RNA |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| snoRNA | Small nucleolar RNA |

| snoRNP | Small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

References

- Matera, A.G.; Terns, R.M.; Terns, M.P. Non-Coding RNAs: Lessons from the Small Nuclear and Small Nucleolar RNAs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, T. Small Nucleolar RNAs: An Abundant Group of Noncoding RNAs with Diverse Cellular Functions. Cell 2002, 109, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachellerie, J.P.; Cavaillé, J.; Hüttenhofer, A. The Expanding snoRNA World. Biochimie 2002, 84, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard-Bourelle, P.; Desjardins-Henri, C.; Mathurin-St-Pierre, D.; Deschamps-Francoeur, G.; Fafard-Couture, É.; Garant, J.-M.; Elela, S.A.; Scott, M.S. snoDB: An Interactive Database of Human snoRNA Sequences, Abundance and Interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D220–D225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, S.; Khanna, A.; Zhang, Z.; Hui, J.; Balwierz, P.J.; Stefan, M.; Beach, C.; Nicholls, R.D.; Zavolan, M.; Stamm, S. The snoRNA MBII-52 (SNORD 115) Is Processed into Smaller RNAs and Regulates Alternative Splicing. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, E.; Sterne-Weiler, T.; O’Hanlon, D.; Blencowe, B.J. Global Mapping of Human RNA-RNA Interactions. Mol. Cell 2016, 62, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M.; Contreras, A.; Ruggero, D. Small RNAs with Big Implications: New Insights into H/ACA snoRNA Function and Their Role in Human Disease. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2015, 6, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, M.; Rai, S.K.; Nakatsu, K.; Deng, Y.; Jijiwa, M. Subverting the Canon: Novel Cancer-Promoting Functions and Mechanisms for snoRNAs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, L.; Wu, P.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, D.; Tian, J. The Potential Role of Small Nucleolar RNAs in Cancers—An Evidence Map. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 3851–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.-J.; Xiang, Y.; Li, C.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Hawke, D.H.; Park, P.K.; Diao, L.; et al. A Pan-Cancer Analysis of the Expression and Clinical Relevance of Small Nucleolar RNAs in Human Cancer. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 1968–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Wen, J.; Huang, Z.; Chen, X.-P.; Zhang, B.-X.; Chu, L. Small Nucleolar RNAs: Insight Into Their Function in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Toden, S.; Weng, W.; Shigeyasu, K.; Miyoshi, J.; Turner, J.; Nagasaka, T.; Ma, Y.; Takayama, T.; Fujiwara, T.; et al. SNORA21—An Oncogenic Small Nucleolar RNA, with a Prognostic Biomarker Potential in Human Colorectal Cancer. eBioMedicine 2017, 22, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.-Z.; Wu, Z.; Chen, W.-J.; Fang, Z.-X.; Yu, X.-N.; Wu, H.-T.; Liu, J. Small Nucleolar RNA and Its Potential Role in the Oncogenesis and Development of Colorectal Cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampen, K.R.; Sulima, S.O.; De Keersmaecker, K. Rise of the Specialized Onco-Ribosomes. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 35205–35206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nait Slimane, S.; Marcel, V.; Fenouil, T.; Catez, F.; Saurin, J.-C.; Bouvet, P.; Diaz, J.-J.; Mertani, H.C. Ribosome Biogenesis Alterations in Colorectal Cancer. Cells 2020, 9, 2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.-Y.; Liu, X.; Qi, Z.-H.; Wang, Q.; Lu, W.-Q.; Zhang, Q.-T.; He, S.-Y.; Wang, Z.-D. Small Nucleolar RNA, C/D Box 16 (SNORD16) Acts as a Potential Prognostic Biomarker in Colon Cancer. Dose Response 2020, 18, 1559325820917829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.-F.; Li, X.-R.; Kong, M.-W. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Roles of Long Non-Coding RNA Small Nucleolar RNA Host Gene 16 in Digestive System Cancers. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2024, 16, 4300–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Dong, Z.; Wang, W.; Wang, M.; Pang, M.; Song, X.; Chen, B.; Zheng, A. SNORA47 Affects Stemness and Chemotherapy Sensitivity via EBF3/RPL11/c-Myc Axis in Luminal A Breast Cancer. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M.; Contreras, A.; Holm, M.; Uechi, T.; Forester, C.M.; Pang, X.; Jackson, C.; Calvert, M.E.; Chen, B.; Quigley, D.A.; et al. A Single H/ACA Small Nucleolar RNA Mediates Tumor Suppression Downstream of Oncogenic RAS. eLife 2019, 8, e48847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Chu, L. An Oncolytic Adenovirus Expressing SNORD44 and GAS5 Exhibits Antitumor Effect in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 2017, 28, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Yang, F.; Ding, C.-L.; Zhao, L.-J.; Ren, H.; Zhao, P.; Wang, W.; Qi, Z.-T. Small Nucleolar RNA 113-1 Suppresses Tumorigenesis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Mol. Cancer 2014, 13, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siprashvili, Z.; Webster, D.E.; Johnston, D.; Shenoy, R.M.; Ungewickell, A.J.; Bhaduri, A.; Flockhart, R.; Zarnegar, B.J.; Che, Y.; Meschi, F.; et al. The Noncoding RNAs SNORD50A and SNORD50B Bind K-Ras and Are Recurrently Deleted in Human Cancer. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.-Y.; Rodriguez, C.; Guo, P.; Sun, X.; Talbot, J.T.; Zhou, W.; Petros, J.; Li, Q.; Vessella, R.L.; Kibel, A.S.; et al. SnoRNA U50 Is a Candidate Tumor-Suppressor Gene at 6q14.3 with a Mutation Associated with Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008, 17, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.-Y.; Guo, P.; Boyd, J.; Sun, X.; Li, Q.; Zhou, W.; Dong, J.-T. Implication of snoRNA U50 in Human Breast Cancer. J. Genet. Genom. 2009, 36, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Ye, M.-H.; Lv, S.-G.; Wang, Q.-X.; Wu, M.-J.; Xiao, B.; Kang, C.-S.; Zhu, X.-G. SNORD47, a Box C/D snoRNA, Suppresses Tumorigenesis in Glioblastoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 43953–43966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Xie, W.; Meng, S.; Kang, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, L.; Wang, C. Small Nucleolar RNAs and Their Comprehensive Biological Functions in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cells 2022, 11, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Chang, L.; Wang, H.; Ma, W.; Peng, Q.; Yuan, Y. Clinical Significance of C/D Box Small Nucleolar RNA U76 as an Oncogene and a Prognostic Biomarker in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2018, 42, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Han, L.; Wei, J.; Zhang, K.; Shi, Z.; Duan, R.; Li, S.; Zhou, X.; Pu, P.; Zhang, J.; et al. SNORD76, a Box C/D snoRNA, Acts as a Tumor Suppressor in Glioblastoma. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janin, M.; Coll-SanMartin, L.; Esteller, M. Disruption of the RNA Modifications That Target the Ribosome Translation Machinery in Human Cancer. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, N.J.; Bohnsack, M.T. The Box C/D and H/ACA snoRNPs: Key Players in the Modification, Processing and the Dynamic Folding of Ribosomal RNA. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2012, 3, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Lee, J.-S.; Ni, C.; Guo, J.; Chen, E.; Wang, S.; Acharya, A.; Chang, T.-C.; et al. A Non-Canonical Role for a Small Nucleolar RNA in Ribosome Biogenesis and Senescence. Cell 2024, 187, 4770–4789.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Bao, H.-J.; Li, Q.-H.; Xian, J.-Y.; Lu, B.-F.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, S. SNORD60 Promotes the Tumorigenesis and Progression of Endometrial Cancer through Binding PIK3CA and Regulating PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Mol. Carcinog. 2023, 62, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, D.G.; Roberts, J.T.; King, V.M.; Houserova, D.; Barnhill, E.C.; Crucello, A.; Polska, C.J.; Brantley, L.W.; Kaufman, G.C.; Nguyen, M.; et al. Human snoRNA-93 Is Processed into a microRNA-like RNA That Promotes Breast Cancer Cell Invasion. NPJ Breast Cancer 2017, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, Y.; Rederstorff, M. SnoRNAs and the Emerging Class of sdRNAs: Multifaceted Players in Oncogenesis. Biochimie 2019, 164, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens-Uzunova, E.S.; Hoogstrate, Y.; Kalsbeek, A.; Pigmans, B.; Vredenbregt-van den Berg, M.; Dits, N.; Nielsen, S.J.; Baker, A.; Visakorpi, T.; Bangma, C.; et al. C/D-Box snoRNA-Derived RNA Production Is Associated with Malignant Transformation and Metastatic Progression in Prostate Cancer. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 17430–17444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Qin, H.; Chen, S.; Zhao, Y. C/D Box Small Nucleolar RNA SNORD104 Promotes Endometrial Cancer by Regulating the 2′-O-Methylation of PARP1. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Sun, L.-Y.; Luo, X.-Q.; Pan, Q.; Sun, Y.-M.; Zeng, Z.-C.; Chen, T.-Q.; Huang, W.; Fang, K.; Wang, W.-T.; et al. Chromatin-Associated Orphan snoRNA Regulates DNA Damage-Mediated Differentiation via a Non-Canonical Complex. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Shi, Q.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, X. Dicer-Independent snRNA/snoRNA-Derived Nuclear RNA 3 Regulates Tumor-Associated Macrophage Function by Epigenetically Repressing Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Transcription. Cancer Commun. 2021, 41, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Feng, C.; Wang, S.; Shi, L.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Lan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Qiang, W.; Ji, M.; et al. The Noncoding RNAs SNORD50A and SNORD50B-Mediated TRIM21-GMPS Interaction Promotes the Growth of P53 Wild-Type Breast Cancers by Degrading P53. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 2450–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalho, S.; Dopler, A.; Faller, W.J. Ribosome Specialization in Cancer: A Spotlight on Ribosomal Proteins. NAR Cancer 2024, 6, zcae029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebright, R.Y.; Lee, S.; Wittner, B.S.; Niederhoffer, K.L.; Nicholson, B.T.; Bardia, A.; Truesdell, S.; Wiley, D.F.; Wesley, B.; Li, S.; et al. Deregulation of Ribosomal Protein Expression and Translation Promotes Breast Cancer Metastasis. Science 2020, 367, 1468–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacchini, F.; Barozzi, C.; Venturi, G.; Montanaro, L. How snoRNAs Can Contribute to Cancer at Multiple Levels. NAR Cancer 2024, 6, zcae005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Qin, W.; Lu, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Sun, T.; Hu, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; et al. Long Noncoding RNA ZFAS1 Promoting Small Nucleolar RNA-Mediated 2′-O-Methylation via NOP58 Recruitment in Colorectal Cancer. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anders, S.; Reyes, A.; Huber, W. Detecting Differential Usage of Exons from RNA-Seq Data. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 2008–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, S.; Stamm, S. The snoRNA HBII-52 Regulates Alternative Splicing of the Serotonin Receptor 2C. Science 2006, 311, 230–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazeley, P.S.; Shepelev, V.; Talebizadeh, Z.; Butler, M.G.; Fedorova, L.; Filatov, V.; Fedorov, A. snoTARGET Shows That Human Orphan snoRNA Targets Locate Close to Alternative Splice Junctions. Gene 2008, 408, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Wilusz, J.E. Short Intronic Repeat Sequences Facilitate Circular RNA Production. Genes. Dev. 2014, 28, 2233–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falaleeva, M.; Surface, J.; Shen, M.; de la Grange, P.; Stamm, S. SNORD116 and SNORD115 Change Expression of Multiple Genes and Modify Each Other’s Activity. Gene 2015, 572, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Tang, J.; Wang, H.; Guo, X.; Tu, C.; Li, Z. The Crosstalk between Alternative Splicing and Circular RNA in Cancer: Pathogenic Insights and Therapeutic Implications. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2024, 29, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taft, R.J.; Glazov, E.A.; Lassmann, T.; Hayashizaki, Y.; Carninci, P.; Mattick, J.S. Small RNAs Derived from snoRNAs. RNA 2009, 15, 1233–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ender, C.; Krek, A.; Friedländer, M.R.; Beitzinger, M.; Weinmann, L.; Chen, W.; Pfeffer, S.; Rajewsky, N.; Meister, G. A Human snoRNA with microRNA-like Functions. Mol. Cell 2008, 32, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, C.I.; Holley, C.L.; Scruggs, B.S.; Sidhu, R.; Brookheart, R.T.; Listenberger, L.L.; Behlke, M.A.; Ory, D.S.; Schaffer, J.E. Small Nucleolar RNAs U32a, U33, and U35a Are Critical Mediators of Metabolic Stress. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Cui, W.; Liu, M.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yin, Y.; Li, Y.; Che, Y.; Zhu, X.; et al. SnoRNAs: The Promising Targets for Anti-Tumor Therapy. J. Pharm. Anal. 2024, 14, 101064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Feng, X.; Liu, M.; Gong, H.; Zhou, X. SnoRNA and lncSNHG: Advances of Nucleolar Small RNA Host Gene Transcripts in Anti-Tumor Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1143980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shav-Tal, Y.; Blechman, J.; Darzacq, X.; Montagna, C.; Dye, B.T.; Patton, J.G.; Singer, R.H.; Zipori, D. Dynamic Sorting of Nuclear Components into Distinct Nucleolar Caps during Transcriptional Inhibition. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 2395–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Bae, B.; Schnabl, S.; Yuan, F.; De Zoysa, T.; Akinyi, M.V.; Le Roux, C.A.; Choquet, K.; Whipple, A.J.; Van Nostrand, E.L. Mapping snoRNA-Target RNA Interactions in an RNA-Binding Protein-Dependent Manner with Chimeric eCLIP. Genome Biol. 2025, 26, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.-J.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Wu, W.; Li, Q.-H.; Xian, J.-Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, S. Box C/D snoRNA SNORD89 Influences the Occurrence and Development of Endometrial Cancer through 2′-O-Methylation Modification of Bim. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Xie, L.; Song, X.; Song, X. Identification of Four snoRNAs (SNORD16, SNORA73B, SCARNA4, and SNORD49B) as Novel Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Diagnosis of Breast Cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; You, Q.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, Y. Serum Exosomal Small Nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) Signatures as a Predictive Biomarker for Benign and Malignant Pulmonary Nodules. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Matas, J.; Duran-Sanchon, S.; Lozano, J.-J.; Ferrero, G.; Tarallo, S.; Pardini, B.; Naccarati, A.; Castells, A.; Gironella, M. SnoRNA Profiling in Colorectal Cancer and Assessment of Non-Invasive Biomarker Capacity by ddPCR in Fecal Samples. iScience 2024, 27, 109283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shang, X.; Yu, M.; Bi, Z.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, L.; Song, X.; Song, X. A Three-snoRNA Signature: SNORD15A, SNORD35B and SNORD60 as Novel Biomarker for Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Deng, J.; Lin, C.; Qi, Z.; Li, Y.; Gu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Shen, L.; et al. Oncogene SCARNA12 as a Potential Diagnostic Biomarker for Colorectal Cancer. Mol. Biomed. 2023, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Abola, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y. Small Nucleolar RNAs in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas. J. Dent. Res. 2025, 104, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lin, P.; Wu, H.-Y.; Li, H.-Y.; He, Y.; Dang, Y.-W.; Chen, G. Genomic Analysis of Small Nucleolar RNAs Identifies Distinct Molecular and Prognostic Signature in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 40, 3346–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, P.; Ghosh, S.; Wang, B.; Heyns, M.; Graham, K.; Mackey, J.R.; Kovalchuk, O.; Damaraju, S. Profiling of Small Nucleolar RNAs by Next Generation Sequencing: Potential New Players for Breast Cancer Prognosis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valleron, W.; Laprevotte, E.; Gautier, E.-F.; Quelen, C.; Demur, C.; Delabesse, E.; Agirre, X.; Prósper, F.; Kiss, T.; Brousset, P. Specific Small Nucleolar RNA Expression Profiles in Acute Leukemia. Leukemia 2012, 26, 2052–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchetti, D.; Mosca, L.; Cutrona, G.; Tuana, G.; Gentile, M.; Fabris, S.; Agnelli, L.; Ciceri, G.; Matis, S.; Massucco, C.; et al. Small Nucleolar RNAs as New Biomarkers in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. BMC Med. Genom. 2013, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valleron, W.; Ysebaert, L.; Berquet, L.; Fataccioli, V.; Quelen, C.; Martin, A.; Parrens, M.; Lamant, L.; de Leval, L.; Gisselbrecht, C.; et al. Small Nucleolar RNA Expression Profiling Identifies Potential Prognostic Markers in Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma. Blood 2012, 120, 3997–4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Ma, J.; Mannoor, K.; Guarnera, M.A.; Shetty, A.; Zhan, M.; Xing, L.; Stass, S.A.; Jiang, F. Genome-Wide Small Nucleolar RNA Expression Analysis of Lung Cancer by next-Generation Deep Sequencing. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E623–E629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannoor, K.; Shen, J.; Liao, J.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, F. Small Nucleolar RNA Signatures of Lung Tumor-Initiating Cells. Mol. Cancer 2014, 13, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okugawa, Y.; Toiyama, Y.; Toden, S.; Mitoma, H.; Nagasaka, T.; Tanaka, K.; Inoue, Y.; Kusunoki, M.; Boland, C.R.; Goel, A. Clinical Significance of SNORA42 as an Oncogene and a Prognostic Biomarker in Colorectal Cancer. Gut 2017, 66, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Chen, L.; Feng, K.-Y.; Hu, X.-H.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Kong, X.-Y.; Huang, T.; Cai, Y.-D. Analysis of Expression Pattern of snoRNAs in Different Cancer Types with Machine Learning Algorithms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehr, S.; Bartschat, S.; Stadler, P.F.; Tafer, H. PLEXY: Efficient Target Prediction for Box C/D snoRNAs. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 279–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirose, T.; Steitz, J.A. Position within the Host Intron Is Critical for Efficient Processing of Box C/D snoRNAs in Mammalian Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 12914–12919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippova, J.A.; Matveeva, A.M.; Zhuravlev, E.S.; Balakhonova, E.A.; Prokhorova, D.V.; Malanin, S.J.; Shah Mahmud, R.; Grigoryeva, T.V.; Anufrieva, K.S.; Semenov, D.V.; et al. Are Small Nucleolar RNAs “CRISPRable”? A Report on Box C/D Small Nucleolar RNA Editing in Human Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, H.J.; Heyn, H.; Moutinho, C.; Esteller, M. CpG Island Hypermethylation-Associated Silencing of Small Nucleolar RNAs in Human Cancer. RNA Biol. 2012, 9, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Yao, D.; Zhang, L.; Hu, X.; Fu, C.; et al. A Plasma SNORD33 Signature Predicts Platinum Benefit in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Patients. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorjani, H.; Kehr, S.; Jedlinski, D.J.; Gumienny, R.; Hertel, J.; Stadler, P.F.; Zavolan, M.; Gruber, A.R. An Updated Human snoRNAome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 5068–5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, D.; Paraqindes, H.; Fafard-Couture, É.; Deschamps-Francoeur, G.; Faucher-Giguère, L.; Bouchard-Bourelle, P.; Abou Elela, S.; Catez, F.; Marcel, V.; Scott, M.S. snoDB 2.0: An Enhanced Interactive Database, Specializing in Human snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D291–D296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Oncogenic Mechanism | snoRNA Examples | Cancer Effect | Therapeutic Potential | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ribosomal Dysfunction | ||||

| Aberrant 2′-O-methylation | SNORD78, SNORD60 | Selective oncogene translation | ASO targeting | [13,32] |

| Loss of pseudouridylation | SNORA24 | Reduced translational fidelity | Expression restoration | [19] |

| Oncoribosomes | SNORD16 | IRES-mediated translation | Ribosome inhibitors | [17] |

| Post-transcriptional Regulation | ||||

| MicroRNA-like functions | sdRNA-93, SNORA42 | Target mRNA regulation | sdRNA inhibitors | [16,33,34] |

| Alternative splicing | SNORD44, SNORD115 (HBII-52) | Pro-tumoral isoforms | Splicing modulators | [5,20,35] |

| mRNA stability | SNORD104 | Enhanced PARP1 expression | PARP inhibitors | [36] |

| Chromatin Remodeling | ||||

| PARP1 interaction | SNORA73 | Genomic instability | PARP inhibitors | [37] |

| Histone modification | sdnRNA3 | TAM immunosuppression | Epigenetic therapy | [38] |

| Signaling Networks | ||||

| Oncogenic pathways | SNORA21, SNORD113-1 | Proliferation/survival | Combination therapy | [12,21] |

| Protein interactions | SNORD50A/B | K-Ras activation | Targeted inhibitors | [22,39] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lorenzo, H.K. Small Nucleolar RNAs as Emerging Players in Cancer Biology and Precision Medicine. Cancers 2025, 17, 3847. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233847

Lorenzo HK. Small Nucleolar RNAs as Emerging Players in Cancer Biology and Precision Medicine. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3847. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233847

Chicago/Turabian StyleLorenzo, Hans Kristian. 2025. "Small Nucleolar RNAs as Emerging Players in Cancer Biology and Precision Medicine" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3847. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233847

APA StyleLorenzo, H. K. (2025). Small Nucleolar RNAs as Emerging Players in Cancer Biology and Precision Medicine. Cancers, 17(23), 3847. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233847