Outcomes After VATS Single Versus Multiple Segmentectomy for cT1N0 Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Study Design and Patient Selection

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Surgical Approach and Workup

2.5. Statistical Analysis

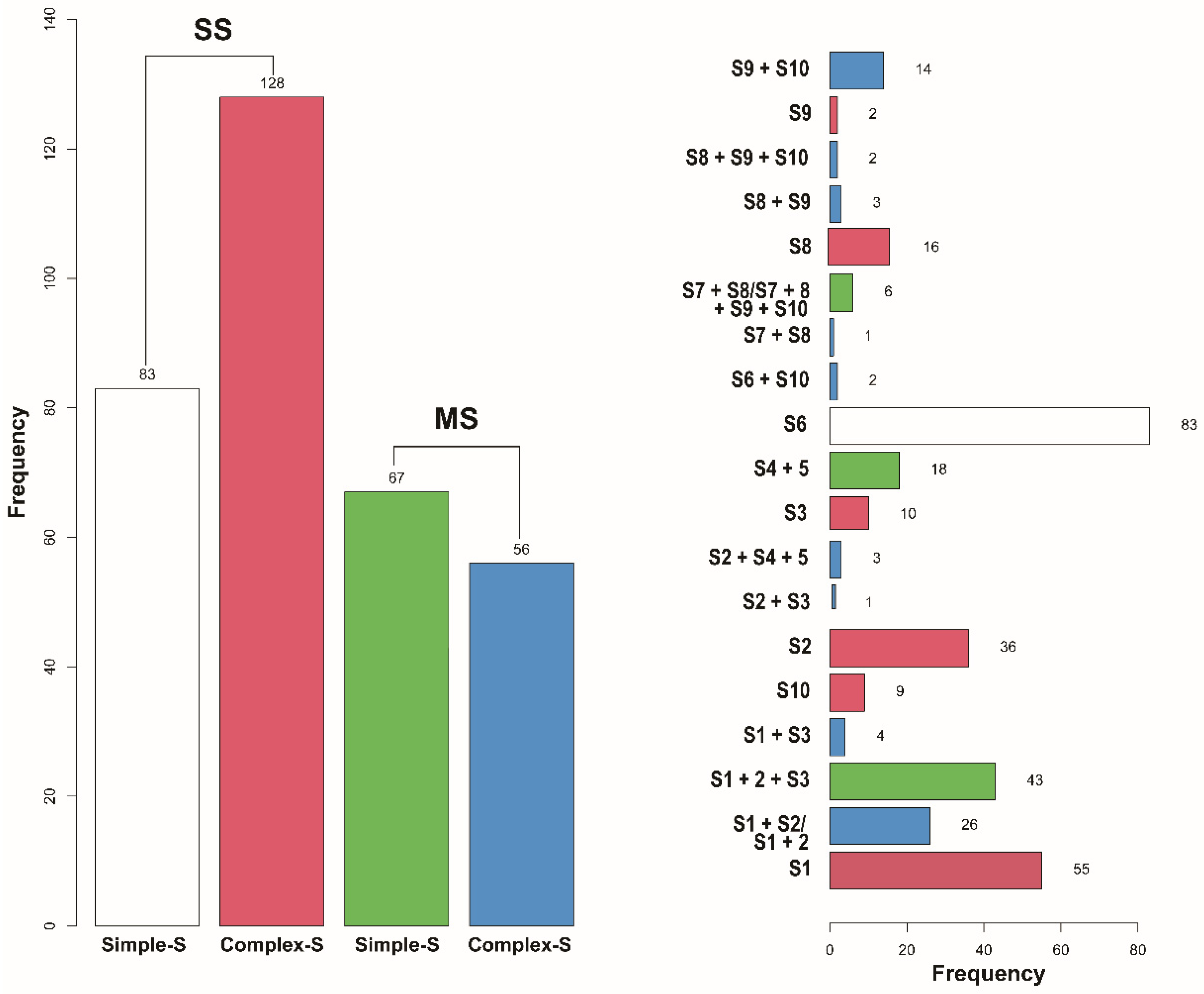

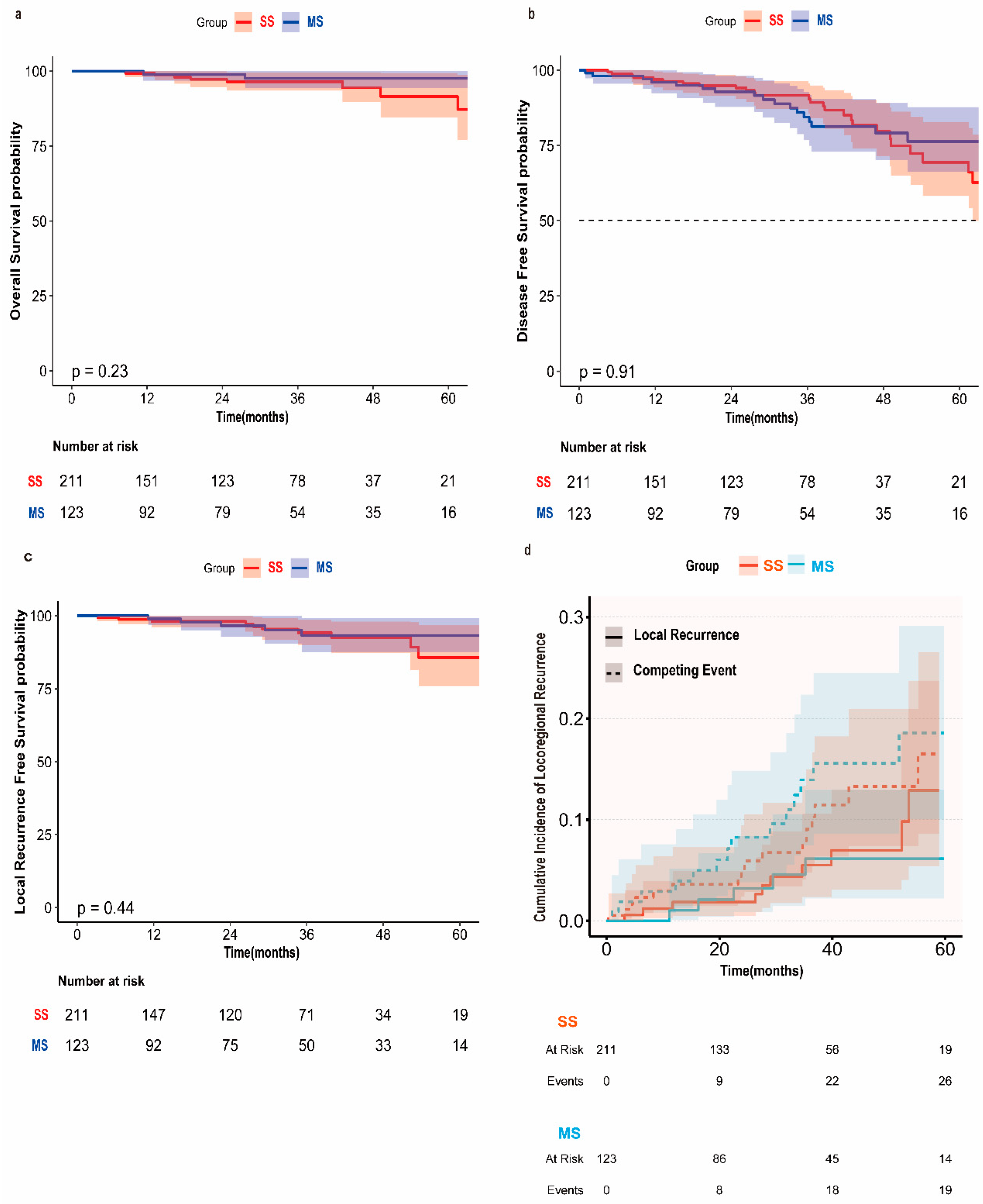

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASA | American Society of Anaesthesiologists |

| AKI | Acute Kidney Injury |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Complex-S | Complex Segmentectomy |

| C/T Ratio | Consolidation/Tumor ratio |

| DFS | Disease-free survival |

| DLCO | Diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide |

| FEV1 | Forced expiratory volume in one second |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| IQR | Inter-quartile range |

| LDCT | Low-dose spiral computed tomography |

| LRFS | Local recurrence-free survival |

| MS | Multiple Segmentectomy |

| NSCLC | Non-small-cell lung cancer |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PSM | Propensity score-matched |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| Simple-S | Simple Segmentectomy |

| SS | Single Segmentectomy |

| TIA/Stroke | Transient Ischemic Attack/Stroke |

| TL | Tumor location. |

| TNM | Tumor–node–metastasis |

| VATS | Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsberg, R.J.; Rubinstein, L.V. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Study Group. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1995, 60, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatis, G.; Leschber, G.; Schwarz, B.; Brintrup, D.L.; Flossdorf, S.; Passlick, B.; Hecker, E.; Kugler, C.; Eichhorn, M.; Krbek, T.; et al. Survival outcomes in a prospective randomized multicenter Phase III trial comparing patients undergoing anatomical segmentectomy versus standard lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer up to 2 cm. Lung Cancer 2022, 172, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saji, H.; Okada, M.; Tsuboi, M.; Nakajima, R.; Suzuki, K.; Aokage, K.; Aoki, T.; Okami, J.; Yoshino, I.; Ito, H.; et al. Segmentectomy versus lobectomy in small-sized peripheral non-small-cell lung cancer (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L): A multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2022, 399, 1607–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altorki, N.; Wang, X.; Kozono, D.; Watt, C.; Landrenau, R.; Wigle, D.; Port, J.; Jones, D.R.; Conti, M.; Ashrafi, A.S.; et al. Lobar or Sublobar Resection for Peripheral Stage IA Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darras, M.; Ojanguren, A.; Forster, C.; Zellweger, M.; Perentes, J.Y.; Krueger, T.; Gonzalez, M. Short-term local control after VATS segmentectomy and lobectomy for solid NSCLC of less than 2 cm. Thorac. Cancer 2021, 12, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winckelmans, T.; Decaluwe, H.; De Leyn, P.; Van Raemdonck, D. Segmentectomy or lobectomy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2020, 57, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, A.; Matsunaga, T.; Fukui, M.; Takamochi, K.; Oh, S.; Suzuki, K. Oncologic outcomes of segmentectomy for stage IA radiological solid-predominant lung cancer >2 cm in maximum tumour size. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2022, 35, ivac246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aokage, K.; Suzuki, K.; Saji, H.; Wakabayashi, M.; Kataoka, T.; Sekino, Y.; Fukuda, H.; Endo, M.; Hattori, A.; Mimae, T.; et al. Segmentectomy for ground-glass-dominant lung cancer with a tumour diameter of 3 cm or less including ground-glass opacity (JCOG1211): A multicentre, single-arm, confirmatory, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 11, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Abdelnour-Berchtold, E.; Bedat, B.; Perentes, J.Y.; Zellweger, M.; Sauvain, M.O.; Christodoulou, M.; Triponez, F.; Karenovics, W.; Krueger, T.; et al. Local control and short-term outcomes after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery segmentectomy versus lobectomy for pT1c pN0 non-small-cell lung cancer. Interdiscip. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2023, 36, ivad037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Brunelli, A.; Stefanou, D.; Zanfrini, E.; Donlagic, A.; Gonzalez, M.; Petersen, R.H. Is segmentectomy potentially adequate for clinical stage IA3 non-small cell lung cancer. Interdiscip. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2025, 40, ivaf064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardillo, G.; Petersen, R.H.; Ricciardi, S.; Patel, A.; Lodhia, J.V.; Gooseman, M.R.; Brunelli, A.; Dunning, J.; Fang, W.; Gossot, D.; et al. European guidelines for the surgical management of pure ground-glass opacities and part-solid nodules: Task Force of the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2023, 64, ezad222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, S.; Lin, X.; Chen, H.; He, R. Lobectomy versus segmentectomy for stage IA3 (T1cN0M0) non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1270030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, E.G.; Chan, P.G.; Mazur, S.N.; Normolle, D.P.; Luketich, J.D.; Landreneau, R.J.; Schuchert, M.J. Outcomes with segmentectomy versus lobectomy in patients with clinical T1cN0M0 non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2021, 161, 1639–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamigaichi, A.; Tsutani, Y.; Kagimoto, A.; Fujiwara, M.; Mimae, T.; Miyata, Y.; Okada, M. Comparing Segmentectomy and Lobectomy for Clinical Stage IA Solid-dominant Lung Cancer Measuring 2.1 to 3 cm. Clin. Lung Cancer 2020, 21, e528–e538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathey-Andrews, C.A.; Potter, A.L.; Srinivasan, D.; Senthil, P.; Elkhatib, H.; Wang, D.; Kumar, A.; Lanuti, M.; Schumacher, L.; Yang, C.J. Segmentectomy vs Lobectomy for Patients With 2- to 3-cm Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Chest 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, A.; Decaluwe, H.; Gonzalez, M.; Gossot, D.; Petersen, R.H.; Augustin, F.; Assouad, J.; Baste, J.M.; Batirel, H.; Falcoz, P.E.; et al. European Society of Thoracic Surgeons expert consensus recommendations on technical standards of segmentectomy for primary lung cancer. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2023, 63, ezad224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottet, B.; Hugen, N.; Sarsam, M.; Couralet, M.; Aguir, S.; Baste, J.M. Performing High-Quality Sublobar Resections: Key Differences Between Wedge Resection and Segmentectomy. Cancers 2024, 16, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolaccini, L.; Mohamed, S.; Diotti, C.; Uslenghi, C.; Cara, A.; Chiari, M.; Casiraghi, M.; Spaggiari, L. Differences in selected postoperative outcomes between simple and complex segmentectomies for lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 49, 107101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedat, B.; Abdelnour-Berchtold, E.; Krueger, T.; Perentes, J.Y.; Zellweger, M.; Triponez, F.; Karenovics, W.; Gonzalez, M. Impact of complex segmentectomies by video-assisted thoracic surgery on peri-operative outcomes. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11, 4109–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, Y.; Tsutani, Y.; Mimae, T.; Tasaki, T.; Miyata, Y.; Okada, M. Surgical Outcomes of Complex Versus Simple Segmentectomy for Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2019, 107, 1032–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.H. Is complex segmentectomy safe? Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 61, 108–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedat, B.; Abdelnour-Berchtold, E.; Perneger, T.; Licker, M.J.; Stefani, A.; Krull, M.; Perentes, J.Y.; Krueger, T.; Triponez, F.; Karenovics, W.; et al. Comparison of postoperative complications between segmentectomy and lobectomy by video-assisted thoracic surgery: A multicenter study. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, R.E.; Brunelli, A.; Walsh, G.; Murthy, S.; Schuchert, M.J.; Varghese, T.K.; Lanuti, M.; Wolf, A.; Keshavarz, H.; Loo, B.W.; et al. Systematic Review of Sublobar Resection for Treatment of High-Risk Patients with Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2025, 37, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shi, Y.; Chen, H.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, K.; Yu, D.; Wei, Y.; Xiong, L. Pulmonary function protection by single-port thoracoscopic segmental lung resection in elderly patients with IA non-small cell lung cancer: A differential matched analysis. Medicine 2023, 102, e33648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, K.; Watanabe, S.I.; Wakabayashi, M.; Yotsukura, M.; Mimae, T.; Hattori, A.; Miyoshi, T.; Isaka, M.; Endo, M.; Yoshioka, H.; et al. Risk Factors for Locoregional Relapse After Segmentectomy: Supplementary Analysis of the JCOG0802/WJOG4607L Trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2025, 20, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, S.; Nasar, A.; Villena-Vargas, J.; Harrison, S.; Lee, B.; Port, J.L.; Altorki, N.; Chow, O.S. All segments are created equal: Locoregional recurrence and survival after single versus multi-segment resection in patients with clinical stage IA ≤2 cm non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2025, 67, ezaf082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattori, A.; Suzuki, K.; Takamochi, K.; Wakabayashi, M.; Sekino, Y.; Tsutani, Y.; Nakajima, R.; Aokage, K.; Saji, H.; Tsuboi, M.; et al. Segmentectomy versus lobectomy in small-sized peripheral non-small-cell lung cancer with radiologically pure-solid appearance in Japan (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L): A post-hoc supplemental analysis of a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Ge, L.; You, S.; Liu, Y.; Ren, Y. Lobectomy versus segmentectomy in patients with stage T (>2 cm and ≤3 cm) N0M0 non-small cell lung cancer: A propensity score matching study. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2022, 17, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qian, B.; Song, Q.; Ma, J.; Cao, H.; Deng, C.; Wang, S.; Ye, T.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Phase III Study of Mediastinal Lymph Node Dissection for Ground Glass Opacity-Dominant Lung Adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 3081–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitlinger, J.; Stasiak, F.; Piccoli, J.; Maffeis, G.; Streit, A.; Wollbrett, C.; Siat, J.; Gauchotte, G.; Renaud, S. What is the appropriate “first lymph node” in the era of segmentectomy for non-small cell lung cancer? Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1078606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.H.; Lee, H.P.; Lee, G.D.; Choi, S.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, D.K.; Park, S.I.; Yun, J.K. Wedge Resection Versus Segmentectomy in Early-Stage Lung Cancer Considering Resection Margin and Lymph Node Evaluation: A Retrospective Study. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2025, 67, ezaf281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Total (n = 334) | SS (n = 211) | MS (n = 123) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean ± SD | 67.7 ± 9.3 | 68.0 ± 9.3 | 67.3 ± 9.3 | 0.528 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.698 | |||

| Male | 161 (48.2) | 100 (47.4) | 61 (49.6) | |

| Female | 173 (51.8) | 111 (52.6) | 62 (50.4) | |

| Smoking History, n (%) | 286 (85.6) | 182 (86.3) | 104 (84.6) | 0.669 |

| BMI, Mean ± SD | 25.6 ± 4.9 | 25.7 ± 4.9 | 25.5 ± 4.9 | 0.746 |

| Previous Cancer, n (%) | 158 (47.3) | 97 (46) | 61 (49.6) | 0.523 |

| CCI, Mean ± SD | 5.3 ± 2.0 | 5.3 ± 1.9 | 5.3 ± 2.0 | 0.922 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 247 (74.0) | 156 (73.9) | 91 (74) | 0.992 |

| COPD, n (%) | 143 (42.8) | 87 (41.2) | 56 (45.5) | 0.444 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 175 (52.4) | 110 (52.1) | 65 (52.8) | 0.9 |

| Cardiovascular Disease, n (%) | 101 (30.2) | 67 (31.8) | 34 (27.6) | 0.43 |

| Atrial Fibrillation, n (%) | 37 (11.1) | 22 (10.4) | 15 (12.2) | 0.619 |

| Diabetes Mellitus, n (%) | 53 (15.9) | 30 (14.2) | 23 (18.7) | 0.28 |

| Renal Insufficiency, n (%) | 39 (11.7) | 26 (12.3) | 13 (10.6) | 0.63 |

| FEV1% Predicted, n (%) | 0.658 | |||

| FEV1% Predicted < 80% | 136 (40.7) | 84 (39.8) | 52 (42.3) | |

| Median FEV1 (%) (IQR) | 85.0 (69.0, 100.0) | 86.0 (70.0, 100.0) | 84.0 (65.0, 99.0) | 0.194 |

| DLCO% Predicted, n (%) | 0.827 | |||

| DLCO% Predicted < 80% | 212 (63.5) | 133 (63) | 79 (64.2) | |

| Median DLCO (%) (IQR) | 70.0 (57.0, 84.8) | 70.0 (57.5, 84.0) | 69.0 (54.5, 86.5) | 0.51 |

| ASA, n (%) | 0.47 * | |||

| ASAI | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.8) | |

| ASAII | 151 (45.2) | 100 (47.4) | 51 (41.5) | |

| ASAIII | 176 (52.7) | 108 (51.2) | 68 (55.3) | |

| ASAIV | 5 (1.5) | 2 (0.9) | 3 (2.4) |

| Variables | Total (n = 334) | SS (n = 211) | MS (n = 123) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lobe, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| RUL | 91 (27.2) | 74 (35.1) | 17 (13.8) | |

| RLL | 82 (24.6) | 63 (29.9) | 19 (15.4) | |

| LUL | 112 (33.5) | 31 (14.7) | 81 (65.9) | |

| LLL | 49 (14.7) | 43 (20.4) | 6 (4.9) | |

| PET SUV, n (%) | 0.731 | |||

| SUVmax < 2.5 | 148 (44.3) | 95 (45) | 53 (43.1) | |

| C/T Ratio, n (%) | 0.506 | |||

| C/T Ratio < 0.5 | 65 (19.5) | 45 (21.3) | 20 (16.3) | |

| 0.5 ≤ C/T Ratio < 1 | 97 (29.0) | 61 (28.9) | 36 (29.3) | |

| C/T Ratio = 1 | 172 (51.5) | 105 (49.8) | 67 (54.5) | |

| Tumor Size(mm), Mean ± SD | 14.7 ± 6.3 | 14.3 ± 6.0 | 15.5 ± 6.7 | 0.115 |

| Tumor Location, n (%) | 0.702 | |||

| Central | 99 (29.6) | 61 (28.9) | 38 (30.9) | |

| Peripheral | 235 (70.4) | 150 (71.1) | 85 (69.1) | |

| Margin Distance(mm), Median (IQR) | 12.0 (6.0, 20.0) | 13.0 (6.5, 22.0) | 11.0 (5.0, 20.0) | 0.038 |

| Margin-to-tumor ratio; Median (IQR) | 0.9 (0.4–1.7) | 0.9 (0.5–1.8) | 0.7 (0.3–1.5) | 0.029 |

| Lymph Nodes Harvested, Mean ± SD | 8.3 ± 5.3 | 8.0 ± 5.5 | 8.8 ± 5.1 | 0.194 |

| Operative Time, Mean ± SD | 122.9 ± 48.7 | 117.4 ± 45.6 | 132.3 ± 52.4 | 0.007 |

| Conversion open thoracotomy, n (%) | 6 (1.8) | 1 (0.5) | 5 (4) | 0.027 * |

| Resection Status, n (%) | 1 * | |||

| R0 | 333 (99.7) | 210 (99.5) | 123 (100) | |

| R1 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Histology, n (%) | 0.603 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 274 (82.0) | 171 (81) | 103 (83.7) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 43 (12.9) | 30 (14.2) | 13 (10.6) | |

| Others | 17 (5.1) | 10 (4.7) | 7 (5.7) | |

| Pleural invasion, n (%) | 40 (12.0) | 24 (11.4) | 16 (13) | 0.657 |

| T Stage, n (%) | 0.1 * | |||

| Tis | 28 (8.4) | 23 (10.9) | 5 (4.1) | |

| T1a | 83 (24.9) | 50 (23.7) | 33 (26.8) | |

| T1b | 131 (39.2) | 85 (40.3) | 46 (37.4) | |

| T1c | 45 (13.5) | 24 (11.4) | 21 (17.1) | |

| T2a | 36 (10.8) | 20 (9.5) | 16 (13) | |

| T3 | 11 (3.3) | 9 (4.3) | 2 (1.6) | |

| N Stage, n (%) | 0.287 * | |||

| N0 | 315 (94.3) | 202 (95.7) | 113 (91.9) | |

| N1 | 7 (2.1) | 2 (0.9) | 5 (4.1) | |

| N2 | 7 (2.1) | 4 (1.9) | 3 (2.4) | |

| Nx | 5 (1.5) | 3 (1.4) | 2 (1.6) | |

| Pathologic Stage, n (%) | 0.29 * | |||

| Stage 0 | 28 (8.4) | 23 (10.9) | 5 (4.1) | |

| Stage IA1 | 80 (24.0) | 49 (23.2) | 31 (25.2) | |

| Stage IA2 | 125 (37.4) | 82 (38.9) | 43 (35) | |

| Stage IA3 | 43 (12.9) | 24 (11.4) | 19 (15.4) | |

| Stage IB | 33 (9.9) | 18 (8.5) | 15 (12.2) | |

| Stage IIB | 18 (5.4) | 11 (5.2) | 7 (5.7) | |

| Stage IIIA | 7 (2.1) | 4 (1.9) | 3 (2.4) | |

| Adjuvant Chemotherapy, n (%) | 49 (14.7) | 32 (15.2) | 17 (13.8) | 0.738 |

| Variables | Total (n = 334) | SS (n = 211) | MS(n = 123) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 28 (8.4) | 13 (6.2) | 15 (12.2) | 0.055 |

| Pulmonary Air Leak, n (%) | 31 (9.3) | 15 (7.1) | 16 (13) | 0.073 |

| Empyema, n (%) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 0.533 * |

| Embolism, n (%) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.6) | 0.135 * |

| Atelectasis, n (%) | 4 (1.2) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (2.4) | 0.143 * |

| Arrhythmia, n (%) | 10 (3.0) | 3 (1.4) | 7 (5.7) | 0.042 * |

| Myocardial Infarction, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 * |

| Ileus, n (%) | 4 (1.2) | 2 (0.9) | 2 (1.6) | 0.627 * |

| Colitis, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | 0.368 * |

| Urosepsis, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 * |

| AKI, n (%) | 12 (3.6) | 6 (2.8) | 6 (4.9) | 0.37 * |

| TIA/Stroke, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 1 * |

| Reoperation, n (%) | 12 (3.6) | 7 (3.3) | 5 (4.1) | 0.765 * |

| Drain duration, n (%) | 0.701 | |||

| >5 days | 51 (15.3) | 31 (14.7) | 20 (16.3) | |

| Median length of drainage days (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0, 4.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) | <0.001 |

| Length of Stay Days, Median (IQR) | 5.0 (4.0, 8.0) | 5.0 (3.0, 7.0) | 6.0 (5.0, 9.5) | <0.001 |

| Recurrence, n (%) | 0.969 | |||

| Local Recurrence | 9 (2.7) | 6 (2.8) | 3 (2.4) | |

| Distant Recurrence | 13 (3.9) | 9 (4.3) | 4 (3.3) | |

| Local combined Distant Recurrence | 7 (2.1) | 5 (2.4) | 2 (1.6) | |

| Perioperative Mortality ≤ 30 days | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Event Type | Group | 12-Month Cumulative Incidence (%) (95% CI) | 36-Month Cumulative Incidence (%) (95% CI) | At-Risk Population (12/36 Months) | Gray Test χ2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Recurrence | SS | 1.85 (0.50–4.93) | 5.51 (2.36–10.62) | 148/71 | 0.73 | 0.394 |

| Local Recurrence | MS | 1.04 (0.09–5.14) | 6.14 (2.21–12.96) | 93/50 | - | - |

| Competing Event | SS | 3.60 (1.48–7.28) | 9.06 (4.79–14.98) | 149/72 | 0.81 | 0.368 |

| Competing Event | MS | 2.89 (0.77–7.56) | 13.94 (7.49–22.35) | 93/51 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, Y.; Zanfrini, E.; Abdelnour-Berchtold, E.; Zellweger, M.; Perentes, J.Y.; Krueger, T.; Gonzalez, M. Outcomes After VATS Single Versus Multiple Segmentectomy for cT1N0 Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233814

Tian Y, Zanfrini E, Abdelnour-Berchtold E, Zellweger M, Perentes JY, Krueger T, Gonzalez M. Outcomes After VATS Single Versus Multiple Segmentectomy for cT1N0 Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233814

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Ye, Edoardo Zanfrini, Etienne Abdelnour-Berchtold, Matthieu Zellweger, Jean Yannis Perentes, Thorsten Krueger, and Michel Gonzalez. 2025. "Outcomes After VATS Single Versus Multiple Segmentectomy for cT1N0 Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233814

APA StyleTian, Y., Zanfrini, E., Abdelnour-Berchtold, E., Zellweger, M., Perentes, J. Y., Krueger, T., & Gonzalez, M. (2025). Outcomes After VATS Single Versus Multiple Segmentectomy for cT1N0 Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers, 17(23), 3814. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233814