Chronic IL-1 Exposure Attenuates RELA- and STAT3-Dependent Synergistic Cytokine Signaling in Prostate Cancer Cell Lines

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Chronic IL-1 Subline Generation and Maintenance

2.3. Cell Treatments

2.3.1. Cytokines

2.3.2. Gene Silencing (siRNA)

2.4. RNA Analysis

2.4.1. RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

2.4.2. Primer Sequences

2.5. Protein Analysis

2.5.1. Western Blot

2.5.2. Antibodies

2.6. Immunofluorescence

2.6.1. Staining

2.6.2. Antibodies

2.6.3. Cell Counts

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Chronic IL-1 Exposure Selects for Cells That Lose or Attenuate Sensitivity to IL-1

3.2. Chronic IL-1-Exposed Cells Can Still Activate IL-6/JAK/STAT Signaling

3.3. IL-1 and IL-6 Axes Crosstalk to Enhance Intracellular Signaling

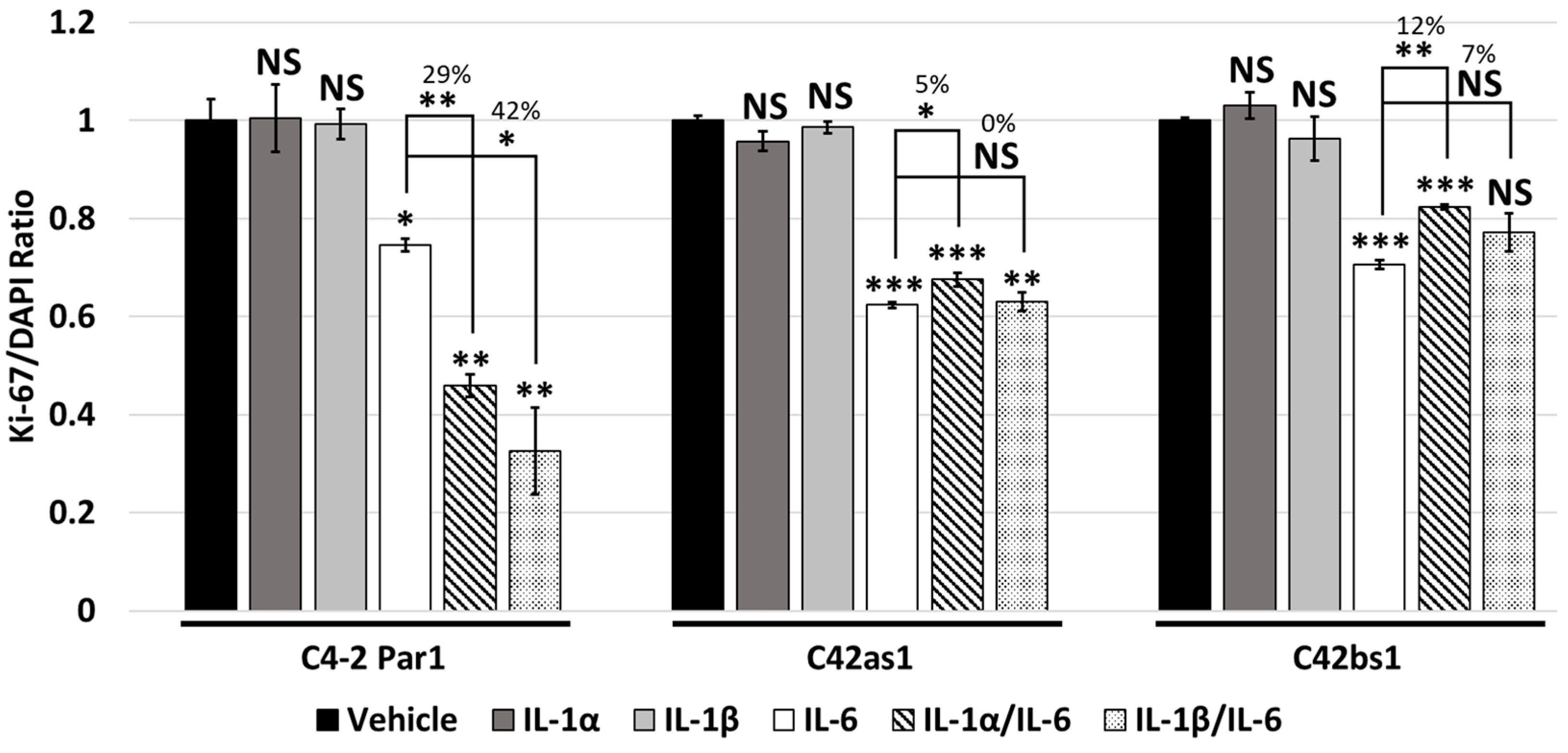

3.4. IL-1 and IL-6 Crosstalk Synergistically Induces Cytostasis

3.5. Chronic IL-1 Exposure Attenuates IL-1/IL-6 Intracellular Signaling Crosstalk and Cytostasis

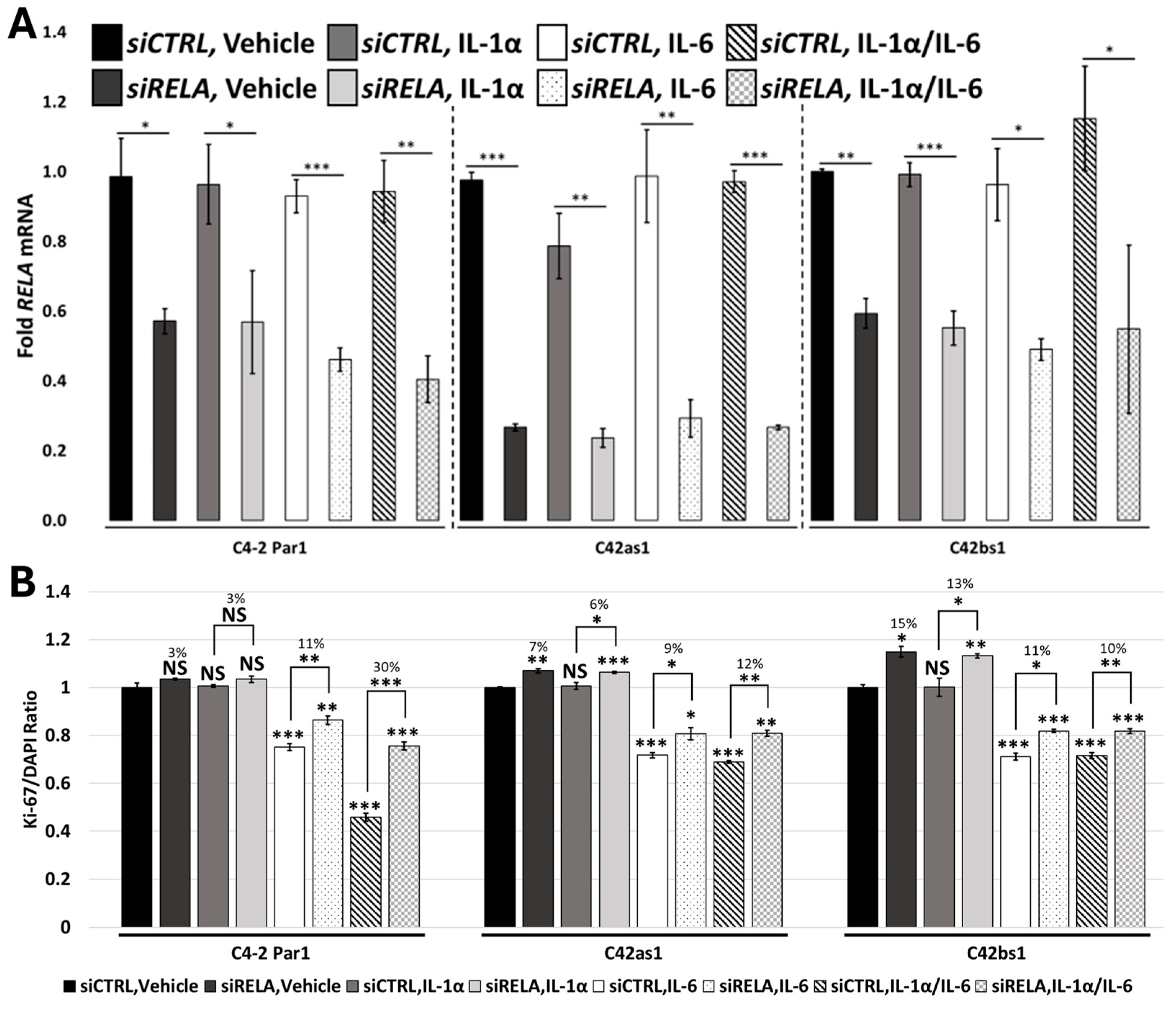

3.6. RELA and STAT3 Are Sufficient to Mediate IL-1/IL-6 Cytostatic Crosstalk

3.7. Chronic IL-1 Exposure Attenuates RELA-Dependent IL-1/IL-6 Cytostatic Crosstalk

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCa | Prostate Cancer |

| IL-1α | Interleukin-1 alpha |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| C4-2 Par1 | C4-2 Parental subline 1 |

| C4-2 Par2 | C4-2 Parental subline 2 |

| C42as1 | C4-2 chronic IL-1α subline 1 |

| C42as2 | C4-2 chronic IL-1α subline 2 |

| C42bs1 | C4-2 chronic IL-1β subline 1 |

| C42bs2 | C4-2 chronic IL-1β subline 2 |

| LNCaP-1 | LNCaP Parental subline 1 |

| LNas1 | LNCaP chronic IL-1α subline 1 |

| LNbs1 | LNCaP chronic IL-1β subline 1 |

References

- Swanton, C.; Bernard, E.; Abbosh, C.; André, F.; Auwerx, J.; Balmain, A.; Bar-Sagi, D.; Bernards, R.; Bullman, S.; DeGregori, J.; et al. Embracing cancer complexity: Hallmarks of systemic disease. Cell 2024, 187, 1589–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coussens, L.M.; Werb, Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002, 420, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, S.; Maddukuri, M.; Yamauchi, S.; Geshow, G.; Delk, N.A. Interleukin-1 and Nuclear Factor Kappa B Signaling Promote Breast Cancer Progression and Treatment Resistance. Cells 2022, 11, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, M.; Dogra, N.; Kyprianou, N. Inflammation as a Driver of Prostate Cancer Metastasis and Therapeutic Resistance. Cancers 2020, 12, 2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrier, S.; Caldefie-Chézet, F.; Vasson, M.-P. IL-1 family in breast cancer: Potential interplay with leptin and other adipocytokines. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Russell, M.R.; Shahriari, K.; Jernigan, D.L.; Lioni, M.I.; Garcia, F.U.; Fatatis, A. Interleukin-1β Promotes Skeletal Colonization and Progression of Metastatic Prostate Cancer Cells with Neuroendocrine Features. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, K.; Shen, F.; Worrede-Mahdi, A.; Liu, Q.; Gong, Y.; Garcia, F.U.; Fatatis, A. Cooperation among heterogeneous prostate cancer cells in the bone metastatic niche. Oncogene 2017, 36, 2846–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Cao, Y.; Jin, T.; Huang, Z.; He, Q.; Mao, M. Role of Interleukin-1 family in bone metastasis of prostate cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 951167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tazaki, E.; Shimizu, N.; Tanaka, R.; Yoshizumi, M.; Kamma, H.; Imoto, S.; Goya, T.; Kozawa, K.; Nishina, A.; Kimura, H. Serum cytokine profiles in patients with prostate carcinoma. Exp. Ther. Med. 2011, 2, 887–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, L.; Yan, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y. Inflammation and tumor progression: Signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oseni, S.O.; Naar, C.; Pavlović, M.; Asghar, W.; Hartmann, J.X.; Fields, G.B.; Esiobu, N.; Kumi-Diaka, J. The Molecular Basis and Clinical Consequences of Chronic Inflammation in Prostatic Diseases: Prostatitis, Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia, and Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, H.C.; Kanchwala, M.; Thomas-Jardin, S.E.; Sandhu, A.; Kanumuri, P.; Nawas, A.F.; Xing, C.; Lin, C.; Frigo, D.E.; Delk, N.A. Chronic IL-1 exposure drives LNCaP cells to evolve androgen and AR independence. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staverosky, J.A.; Zhu, X.-H.; Ha, S.; Logan, S.K. Anti-androgen resistance in prostate cancer cells chronically induced by interleukin-1β. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Urol. 2013, 1, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Culig, Z.; Puhr, M. Interleukin-6 and prostate cancer: Current developments and unsolved questions. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2018, 462, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlstrøm, N.; Jin, Y.; Nenseth, Z.; Kuzu, O.F.; Saatcioglu, F. STAMP2 Expression Mediated by Cytokines Attenuates Their Growth-Limiting Effects in Prostate Cancer Cells. Cancers 2021, 13, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao, J.W.; Hsieh, T.C.; Xu, W.; Sklarew, R.J.; Kancherla, R. Development of human prostate cancer cells to neuroendocrine-like cells by interleukin-1. Int. J. Oncol. 1999, 15, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.; Abdul, M.; Hoosein, N. Modulation of neuroendocrine differentiation in prostate cancer by interleukin-1 and -2. Prostate 1998, 8, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas-Jardin, S.E.; Dahl, H.; Nawas, A.F.; Bautista, M.; Delk, N.A. NF-κB signaling promotes castration-resistant prostate cancer initiation and progression. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 211, 107538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.-D.; Choo, R.; Huang, J. Neuroendocrine Differentiation in Prostate Cancer: A Mechanism of Radioresistance and Treatment Failure. Front. Oncol. 2015, 5, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutt, S.S.; Gao, A.C. Molecular mechanisms of castration-resistant prostate cancer progression. Future Oncol. 2009, 5, 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.P.; Li, J.; Tewari, A.K. Inflammation and prostate cancer: The role of interleukin 6 (IL-6). BJU Int. 2014, 113, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas-Jardin, S.E.; Kanchwala, M.S.; Dahl, H.; Liu, V.; Ahuja, R.; Soundharrajan, R.; Roos, N.; Diep, S.; Sandhu, A.; Xing, C.; et al. Chronic IL-1 Exposed AR+ PCa Cell Lines Show Conserved Loss of IL-1 Sensitivity and Evolve Both Conserved and Unique Differential Gene Expression Profiles. J. Cell. Signal. 2021, 2, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Zhang, L.; Peng, X.; Tu, J.; Li, S.; He, X.; Li, F.; Qiang, J.; Dong, H.; Deng, Q.; et al. IL1R2 Blockade Alleviates Immunosuppression and Potentiates Anti-PD-1 Efficacy in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 2282–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplanov, I.; Carmi, Y.; Kornetsky, R.; Shemesh, A.; Shurin, G.V.; Shurin, M.R.; Dinarello, C.A.; Voronov, E.; Apte, R.N. Blocking IL-1β reverses the immunosuppression in mouse breast cancer and synergizes with anti-PD-1 for tumor abrogation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 1361–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Su, B.; Hung, V.; Luo, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wang, G.; de Graaf, D.; Dinarello, C.A.; Spaner, D.E. IL-1 receptor antagonism reveals a yin-yang relationship between NFκB and interferon signaling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2405644121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lust, J.A.; Lacy, M.Q.; Zeldenrust, S.R.; Witzig, T.E.; Moon-Tasson, L.L.; Dinarello, C.A.; Donovan, K.A. Reduction in C-reactive protein indicates successful targeting of the IL-1/IL-6 axis resulting in improved survival in early stage multiple myeloma. Am. J. Hematol. 2016, 91, 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Nath, K.; Devlin, S.M.; Sauter, C.S.; Palomba, M.L.; Shah, G.; Dahi, P.; Lin, R.J.; Scordo, M.; Perales, M.-A.; et al. CD19 CAR T-cell therapy and prophylactic anakinra in relapsed or refractory lymphoma: Phase 2 trial interim results. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1710–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.C.; Baum, J.; Silvestro, A.; Beste, M.T.; Bharani-Dharan, B.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.A.; Wang, X.; Prescott, M.F.; Krajkovich, L.; et al. Inhibition of IL1β by Canakinumab May Be Effective against Diverse Molecular Subtypes of Lung Cancer: An Exploratory Analysis of the CANTOS Trial. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 5597–5605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Liu, X.; Pan, R.; Zhang, X.; Si, X.; Chen, M.; Wang, M.; Zhang, L. Tocilizumab for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With Concomitant Cachexia: An Observational Study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024, 15, 2815–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alraouji, N.N.; Al-Mohanna, F.H.; Ghebeh, H.; Arafah, M.; Almeer, R.; Al-Tweigeri, T.; Aboussekhra, A. Tocilizumab potentiates cisplatin cytotoxicity and targets cancer stem cells in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 2020, 59, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Huang, J.; Zhong, H.; Shen, N.; Faggioni, R.; Fung, M.; Yao, Y. Targeting interleukin-6 in inflammatory autoimmune diseases and cancers. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 141, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delk, N.A.; Farach-Carson, M.C. Interleukin-6: A bone marrow stromal cell paracrine signal that induces neuroendocrine differentiation and modulates autophagy in bone metastatic PCa cells. Autophagy 2012, 8, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamauchi, S.A.; Dahl-Wilkie, H.; Zaky, M.H.M.; Liu, V.; Onuogu, A.; Abdi, A.; Billa, S.; Javaid, R.; Siddiqui, S.; Mbah, C.; et al. Chronic IL-1 Exposure Attenuates RELA- and STAT3-Dependent Synergistic Cytokine Signaling in Prostate Cancer Cell Lines. Cancers 2025, 17, 3778. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233778

Yamauchi SA, Dahl-Wilkie H, Zaky MHM, Liu V, Onuogu A, Abdi A, Billa S, Javaid R, Siddiqui S, Mbah C, et al. Chronic IL-1 Exposure Attenuates RELA- and STAT3-Dependent Synergistic Cytokine Signaling in Prostate Cancer Cell Lines. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3778. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233778

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamauchi, Stephanie Akemi, Haley Dahl-Wilkie, Mohamed Hussien Mohamed Zaky, Vivian Liu, Adora Onuogu, Ahmed Abdi, Shreya Billa, Rahael Javaid, Sheza Siddiqui, Chisom Mbah, and et al. 2025. "Chronic IL-1 Exposure Attenuates RELA- and STAT3-Dependent Synergistic Cytokine Signaling in Prostate Cancer Cell Lines" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3778. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233778

APA StyleYamauchi, S. A., Dahl-Wilkie, H., Zaky, M. H. M., Liu, V., Onuogu, A., Abdi, A., Billa, S., Javaid, R., Siddiqui, S., Mbah, C., Bankole, O., Wells, S., Greene, S., Falah, R., & Delk, N. A. (2025). Chronic IL-1 Exposure Attenuates RELA- and STAT3-Dependent Synergistic Cytokine Signaling in Prostate Cancer Cell Lines. Cancers, 17(23), 3778. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233778