Feasibility Study on Reusing Recycled Premixed Multi-Material Powder in the Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process for Thermal Management Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Design and Experimental Details

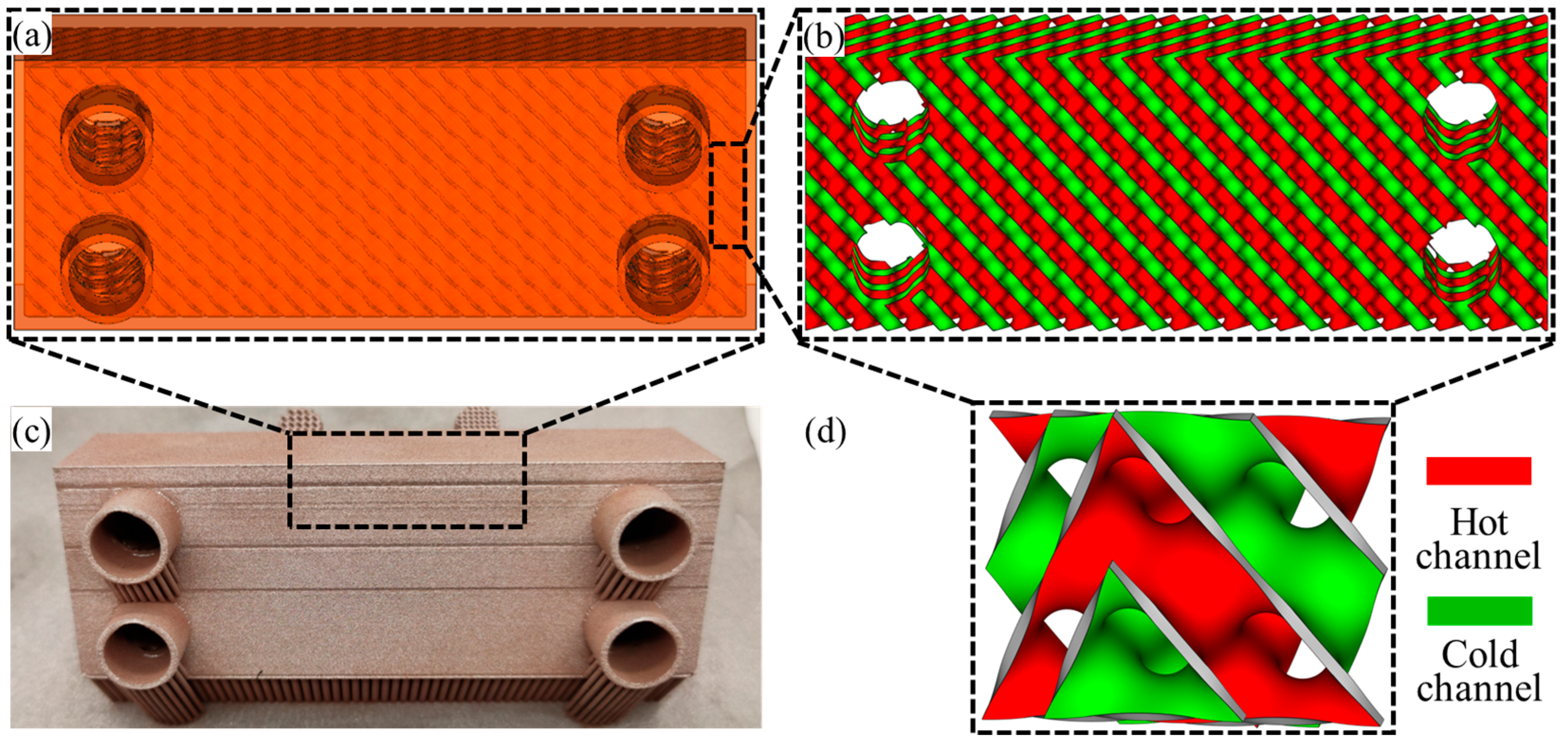

2.1. TPMS Heat Exchanger Design

2.2. Laser Powder Bed Fusion

2.3. Heat Transfer Evaluation

2.4. Characterization

2.5. Experimental and Numerical Procedures

3. Results and Discussion

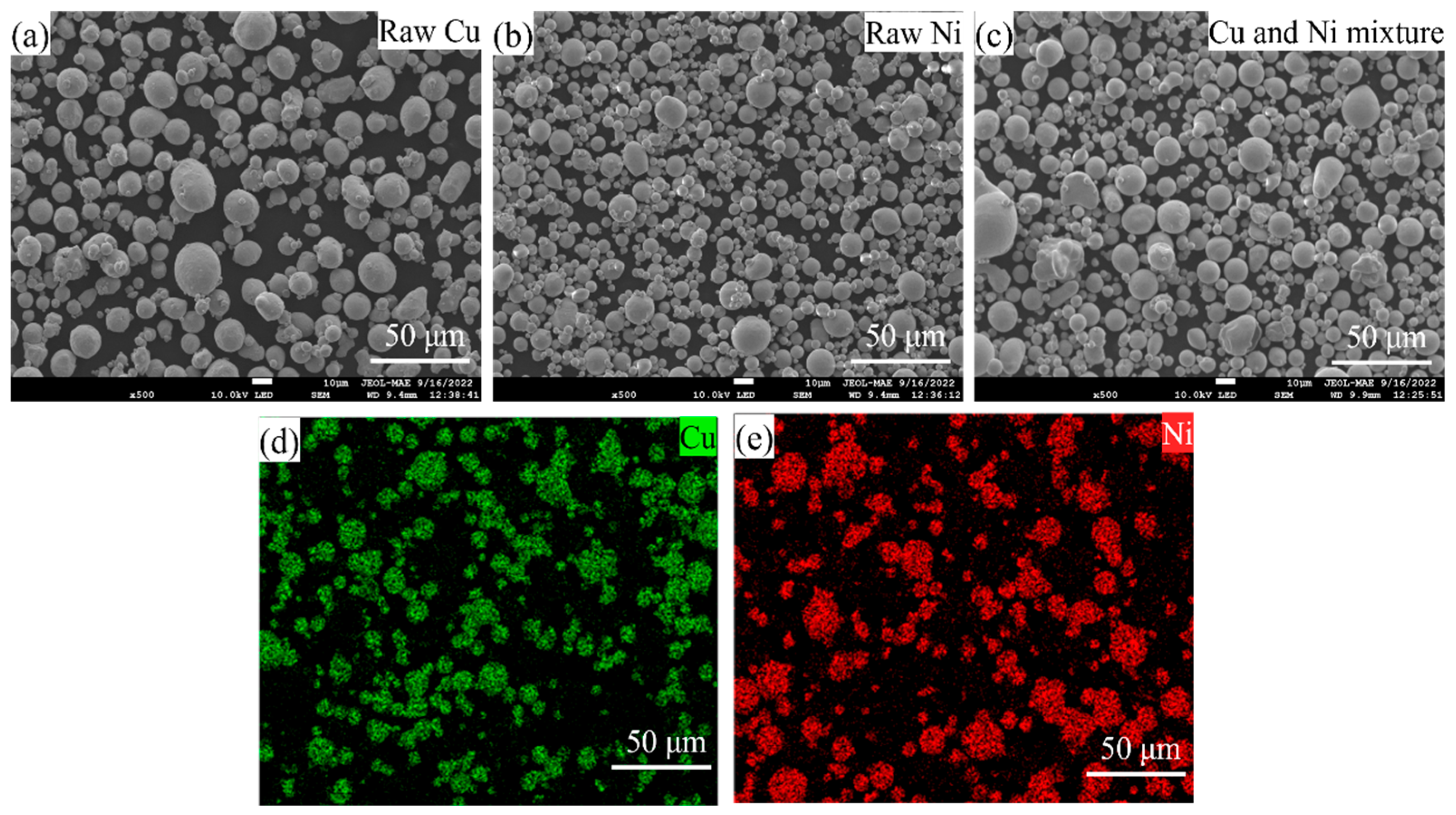

3.1. Microstructure

3.2. Mechanical Properties

3.3. Heat Transfer Characteristics

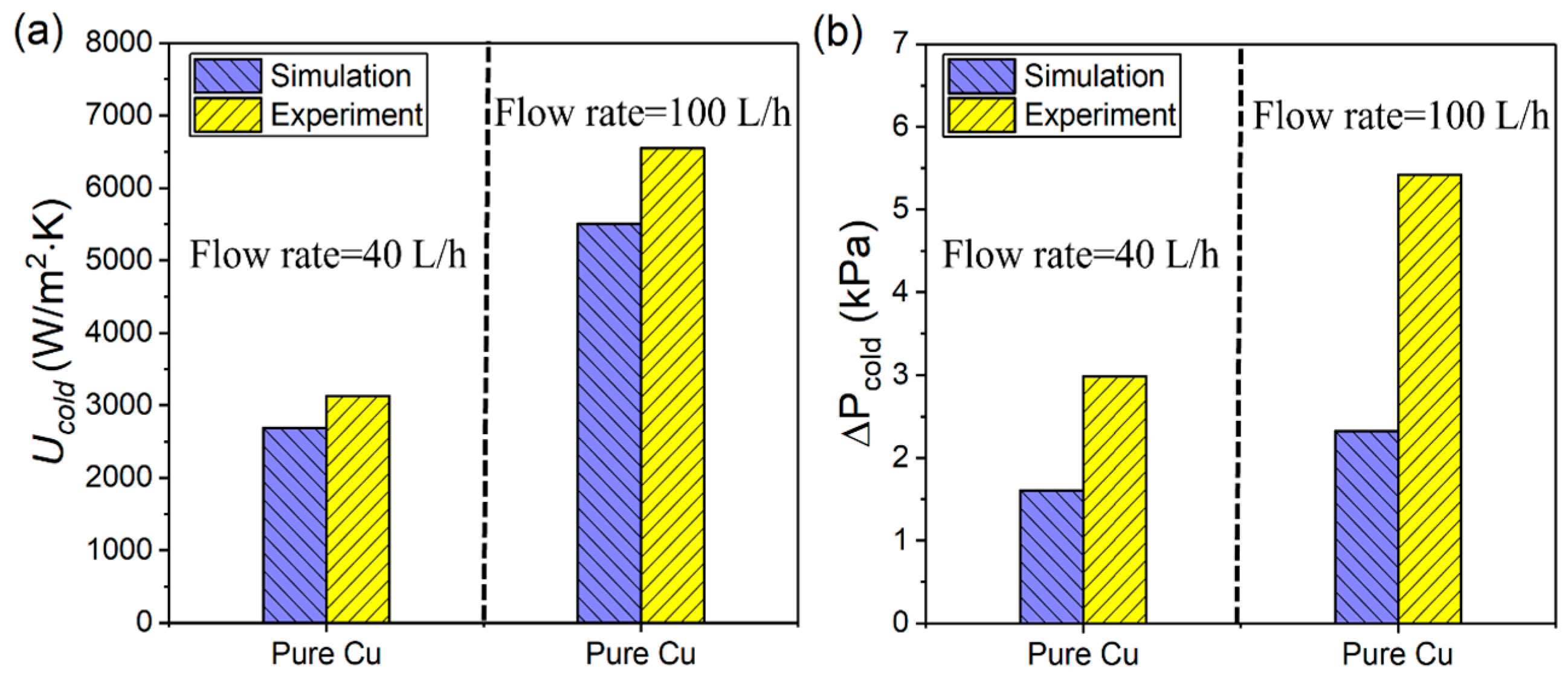

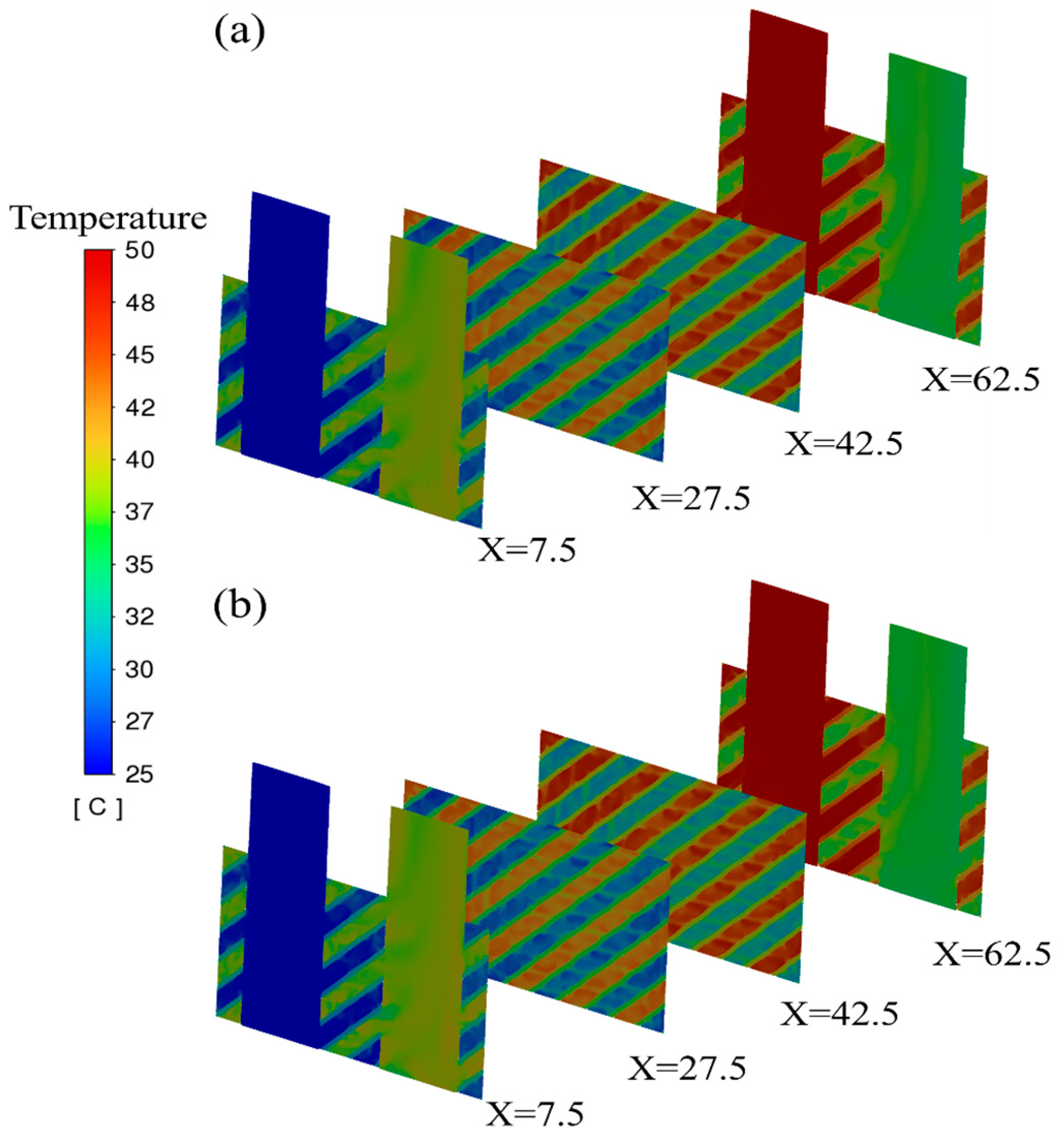

3.4. HE Performance Evaluation

4. Conclusions

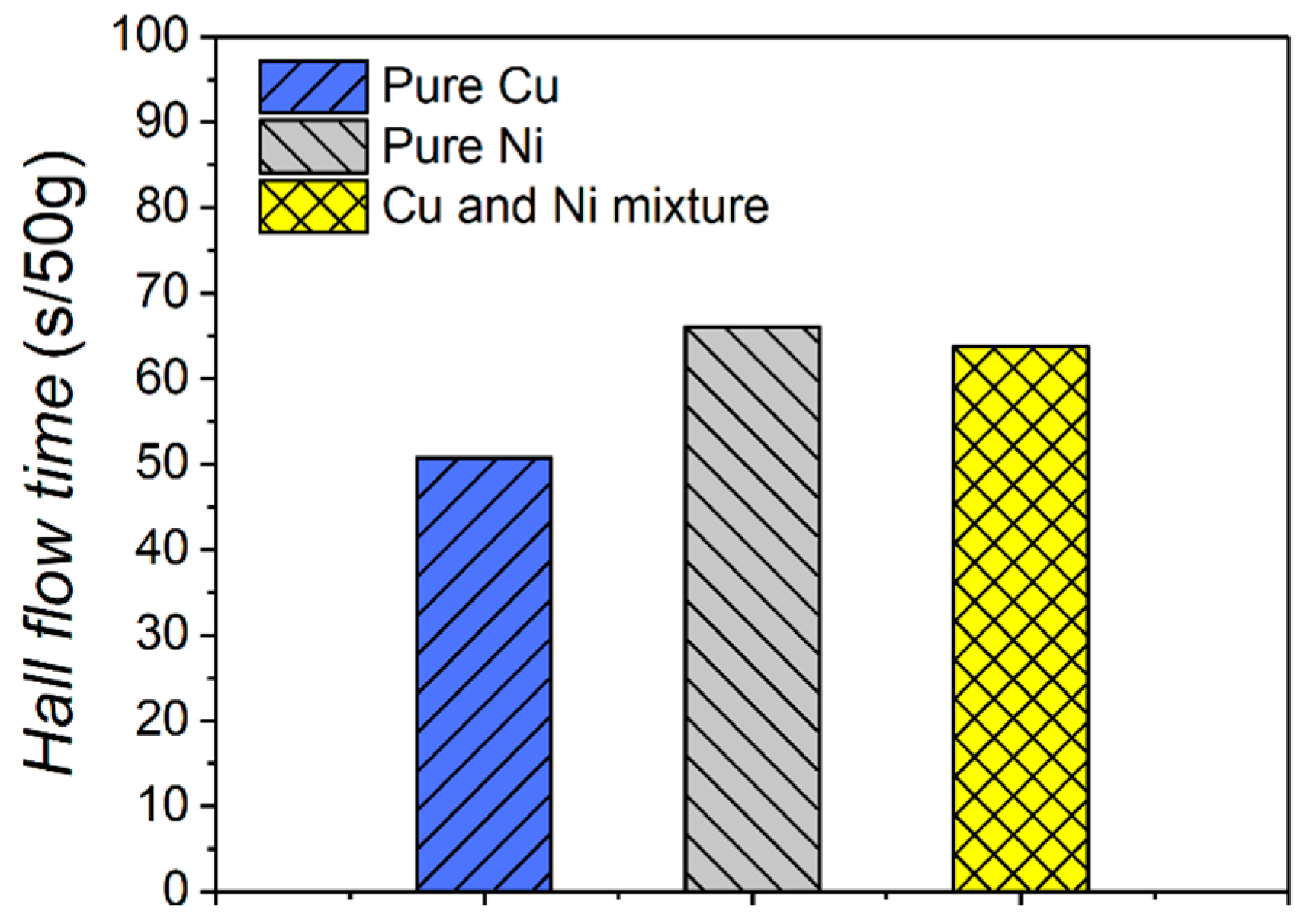

- The Cu and Ni premixture exhibits a morphology comparable to that of virgin Cu and Ni powders, and its flowability lies between the two, approaching that of pure Ni.

- Due to the unalloyed powder, some degree of local inhomogeneities in the composition and texture exists.

- The compression curve of the Cu-Ni alloy shows a long stress plateau, while the tension curve presents an excellent elongation. The total mechanical properties are close to those of other existing products.

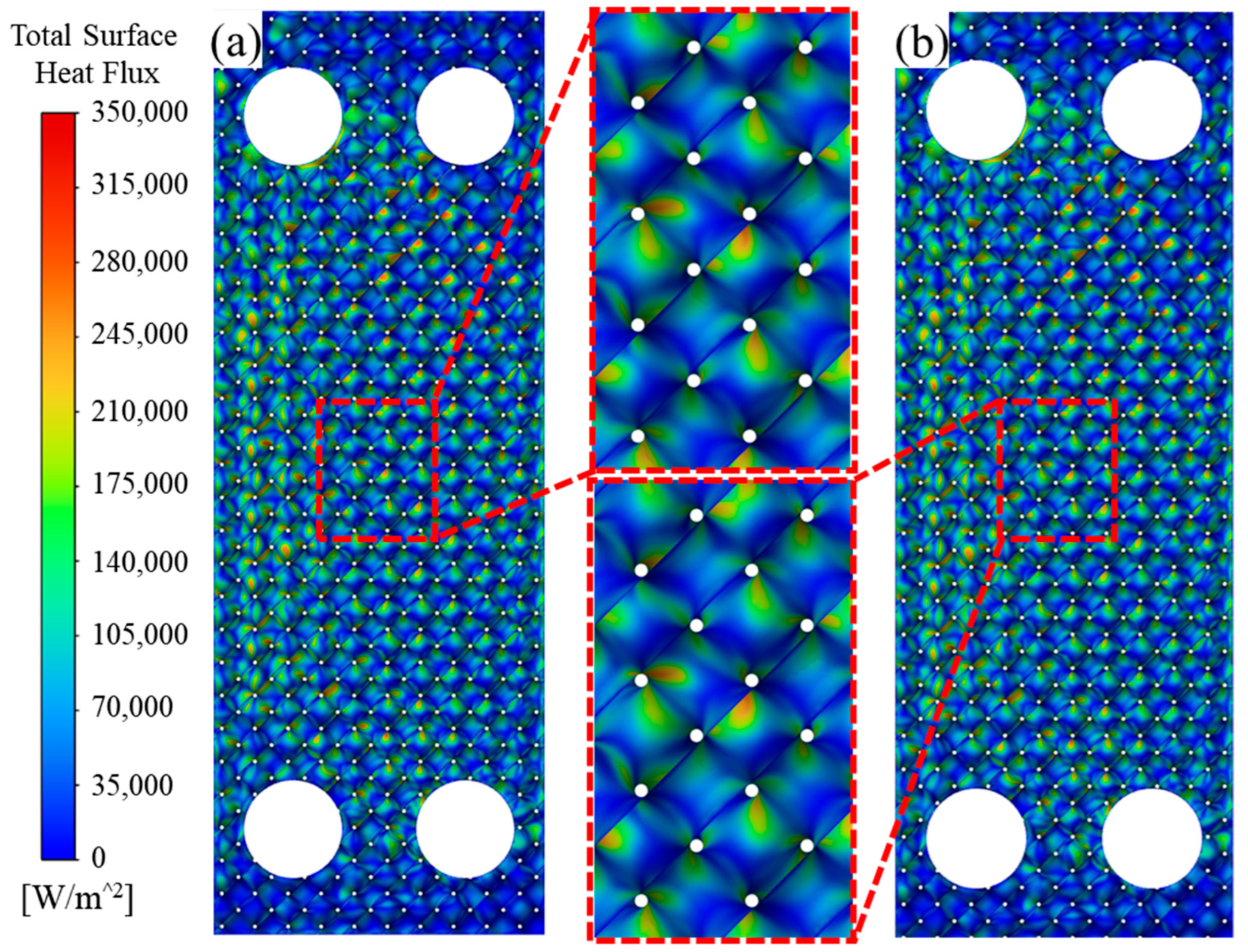

- The simulated total surface heat fluxes are almost identical to each other.

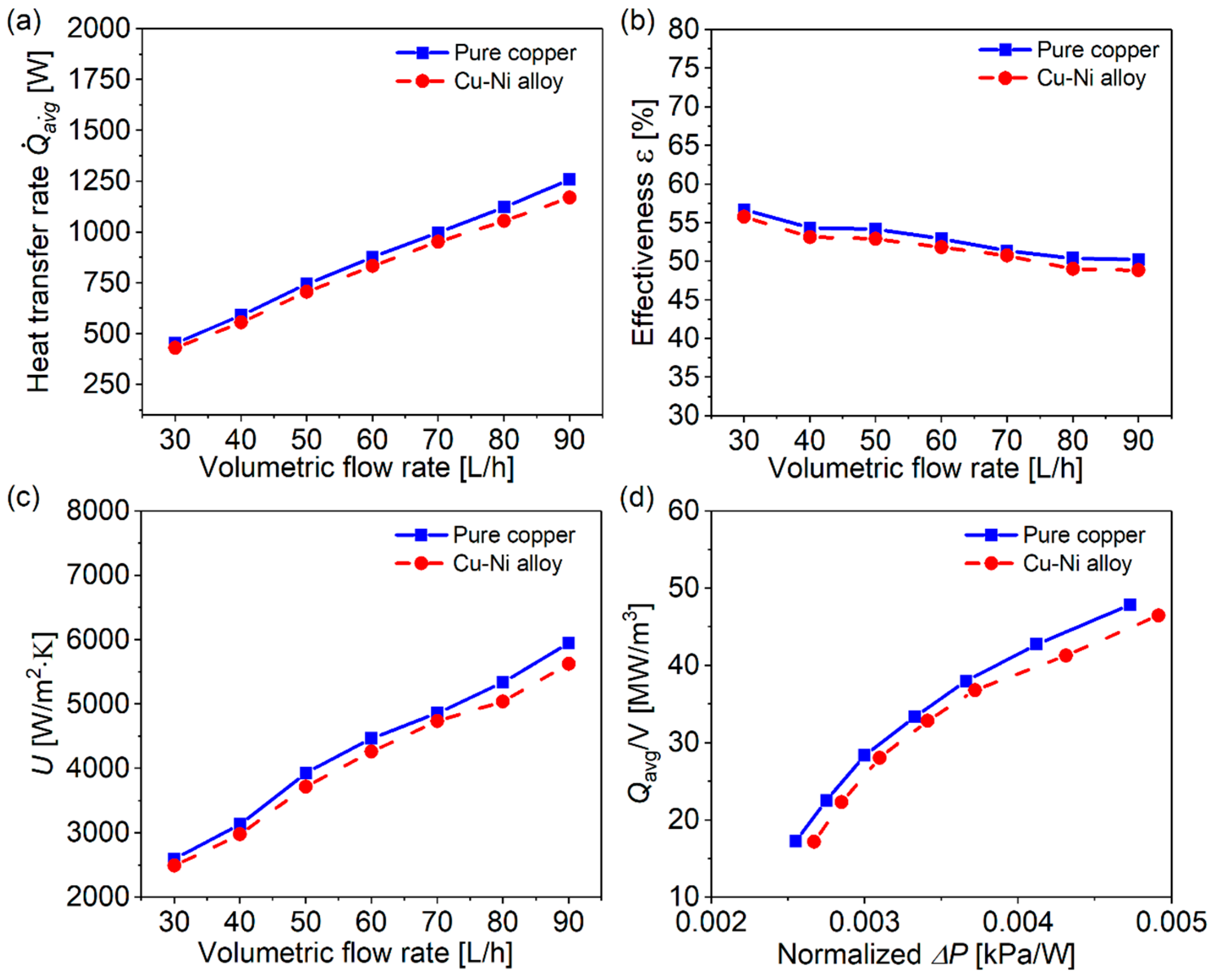

- The measured heat transfer rate and effectiveness of the Cu heat exchanger almost coincide with the curves of the Cu-Ni heat exchanger. The maximum difference in heat transfer effectiveness is within 1.3%. The slight variation in heat transfer performance can be attributed to the difference in thermal conductivity between pure copper and the Cu–Ni alloy.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gradl, P. Metal Additive Manufacturing for Spaceflight. In Proceedings of the Aerospace & Defense Manufacturing & R&D Summit, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Blakey-Milner, B.; Gradl, P.; Snedden, G.; Brooks, M.; Pitot, J.; Lopez, E.; Leary, M.; Berto, F.; du Plessis, A. Metal additive manufacturing in aerospace: A review. Mater. Des. 2021, 209, 110008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, R.; Barreiros, F.; Alves, L.; Romeiro, F.; Vasco, J.; Santos, M.; Marto, C. Additive manufacturing tooling for the automotive industry. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 92, 1671–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasco, J.C. Additive manufacturing for the automotive industry. In Additive Manufacturing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 505–530. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Pisignano, D.; Zhao, Y.; Xue, J. Advances in medical applications of additive manufacturing. Engineering 2020, 6, 1222–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M. Additive manufacturing processes in medical applications. Materials 2021, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Rännar, L.-E.; Liu, L.; Koptyug, A.; Wikman, S.; Olsen, J.; Cui, D.; Shen, Z. Additive manufacturing of 316L stainless steel by electron beam melting for nuclear fusion applications. J. Nucl. Mater. 2017, 486, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.; Haley, J.; Cramer, C.; Shafer, O.; Elliott, A.; Peter, W.; Love, L.; Dehoff, R. Considerations for Application of Additive Manufacturing to Nuclear Reactor Core Components; Oak Ridge National Lab. (ORNL): Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2019.

- Tian, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhao, D.; Huang, Y.; Pan, J. Numerical analysis of powder bed generation and single track forming for selective laser melting of SS316L stainless steel. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 58, 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarji, K.; Ravi Kumar, Y.; Jinoop, A.; Paul, C.; Bindra, K. Effect of heat-treatment on the microstructure, mechanical properties and corrosion behaviour of SS 316 structures built by laser directed energy deposition based additive manufacturing. Met. Mater. Int. 2021, 27, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, B.; Froes, F.S. The additive manufacturing (AM) of titanium alloys. Met. Powder Rep. 2017, 72, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froes, F.; Dutta, B. The additive manufacturing (AM) of titanium alloys. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 1019, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Babu, S.S.; Raghavan, N.; Raplee, J.; Foster, S.J.; Frederick, C.; Haines, M.; Dinwiddie, R.; Kirka, M.; Plotkowski, A.; Lee, Y. Additive manufacturing of nickel superalloys: Opportunities for innovation and challenges related to qualification. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2018, 49, 3764–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhang, L.; Andersson, J.; Ojo, O. Additive manufacturing of 18% nickel maraging steels: Defect, structure and mechanical properties: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 120, 227–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulkhair, N.T.; Simonelli, M.; Parry, L.; Ashcroft, I.; Tuck, C.; Hague, R. 3D printing of Aluminium alloys: Additive Manufacturing of Aluminium alloys using selective laser melting. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2019, 106, 100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altıparmak, S.C.; Yardley, V.A.; Shi, Z.; Lin, J. Challenges in additive manufacturing of high-strength aluminium alloys and current developments in hybrid additive manufacturing. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2021, 4, 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorganji, B.; Ott, E.; Kelkar, R.; Wessman, A.; Jamshidinia, M. Materials ecosystem for additive manufacturing powder bed fusion processes. JOM 2020, 72, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelis, E.; Clemente, M.; Kerwien, S.; Ravindra, N.M.; Hespos, M.R. Metallurgical and mechanical evaluation of 4340 steel produced by direct metal laser sintering. JOM 2015, 67, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, H.; Karimi, P.; Hryha, E.; Nyborg, L. Effect of powder recycling on the fracture behavior of electron beam melted alloy 718. Powder Met. Prog. 2018, 18, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tradowsky, U.; White, J.; Ward, R.; Read, N.; Reimers, W.; Attallah, M. Selective laser melting of AlSi10Mg: Influence of post-processing on the microstructural and tensile properties development. Mater. Des. 2016, 105, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delacroix, T.; Lomello, F.; Schuster, F.; Maskrot, H.; Garandet, J.-P. Influence of powder recycling on 316L stainless steel feedstocks and printed parts in laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 50, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Ali, U.; Sarker, D.; Marzbanrad, E.; Choi, K.; Mahmoodkhani, Y.; Toyserkani, E. Study of powder recycling and its effect on printed parts during laser powder-bed fusion of 17-4 PH stainless steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2020, 278, 116522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Chueh, Y.-H. 3D printing of multiple metallic materials via modified selective laser melting. CIRP Ann. 2018, 67, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wits, W.W.; Amsterdam, E. Graded structures by multi-material mixing in laser powder bed fusion. CIRP Ann. 2021, 70, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Gao, S.; Wang, L.; Ding, J.; Lu, Y.; Wen, Y.; Qu, X.; Zhang, B.; Song, X. Full-composition-gradient in-situ alloying of Cu–Ni through laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 85, 104166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhang, B.; Narayan, R.L.; Wang, P.; Song, X.; Zhao, H.; Ramamurty, U.; Qu, X. Laser powder bed fusion of compositionally graded CoCrMo-Inconel 718. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 40, 101926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivel, Y. New approach to multi-material processing in selective laser melting. Phys. Procedia 2016, 83, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, H. Mechanische Verfahrenstechnik: Berechnung und Projektierung; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, M.; Anstaett, C.; Horn, M.; Herzer, F.; Schlick, G.; Seidel, C.; Schilp, J.; Reinhart, G. Potentials and challenges of multi-material processing by laser-based powder bed fusion. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual International Solid Freeform Symposium, Austin, TX, USA, 13–15 August 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Ning, H.; Li, N.; Tang, G.; Ma, Y.; Li, Z.; Nan, X.; Li, X. Thermal-hydraulic performance of TPMS-based regenerators in combined cycle aero-engine. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 250, 123510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Wang, J.; Deng, H. Numerical investigation into thermo-hydraulic characteristics and mixing performance of triply periodic minimal surface-structured heat exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 230, 120748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Wang, J.; Qiu, X.; Yan, L.; Yu, B.; Shi, J.; Chen, J. Numerical and experimental investigation of ultra-compact triply periodic minimal surface heat exchangers with high efficiency. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 233, 125984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Gao, F.; Hu, W. Design, modeling and characterization on triply periodic minimal surface heat exchangers with additive manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual International Solid Freeform Symposium, Austin, TX, USA, 12–14 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Chen, K.; Zeng, M.; Ma, T.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, Z. Investigation on flow and heat transfer in various channels based on triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS). Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 283, 116955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Qu, S.; Ding, J.; Liu, H.; Song, X. Influence of cell size and its gradient on thermo-hydraulic characteristics of triply periodic minimal surface heat exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 232, 121098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genceli, O. Heat Exchangers; Birsen Book Company: Istanbul, Turkey, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Incropera, F.P.; DeWitt, D.P.; Bergman, T.L.; Lavine, A.S. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1996; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, T.; Al-Hajri, E.; Paul, M.C.; Nithiarasu, P.; Kumar, S. High performance, microarchitected, compact heat exchanger enabled by 3D printing. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 210, 118339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femmer, T.; Kuehne, A.J.; Wessling, M. Estimation of the structure dependent performance of 3-D rapid prototyped membranes. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 273, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, K.; Zeng, M.; Ma, T.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, Z. Assessment of flow and heat transfer of triply periodic minimal surface based heat exchangers. Energy 2023, 282, 128806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renon, C.; Jeanningros, X. A numerical investigation of heat transfer and pressure drop correlations in Gyroid and Diamond TPMS-based heat exchanger channels. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 239, 126599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnati, S.; Liou, F.F.; Newkirk, J.W. Characterization of copper–nickel alloys fabricated using laser metal deposition and blended powder feedstocks. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 103, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, C.; Butters, M. Investigation in Hardsurfacing a Nickel-Copper Alloy (MONEL400); Brookhaven National Lab. (BNL): Upton, NY, USA, 2001.

- Qu, S.; Ding, J.; Fu, J.; Fu, M.; Zhang, B.; Song, X. High-precision laser powder bed fusion processing of pure copper. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 48, 102417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ding, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Song, X.; Zhang, S. A 3D-printed CuNi alloy catalyst with a triply periodic minimal surface for the reverse water-gas shift reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Chavan, H.; Kumar, A. Effect of cell size and wall thickness on the compression performance of triply periodic minimal surface based AlSi10Mg lattice structures. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 193, 111214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenych, O.; Kostryzhev, A.; Shen, C.; Pan, Z.; Li, H.; van Duin, S. Precipitation strengthening in Ni–Cu alloys fabricated using wire arc additive manufacturing technology. Metals 2019, 9, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.; Ackerman, M.; Wu, K.; Oh, S.; Havill, T. Thermal conductivity of ten selected binary alloy systems. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1978, 7, 959–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, B.; Bigham, S. Performance evaluation of hi-k lung-inspired 3D-printed polymer heat exchangers. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 204, 117993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mesh | (°C) | Deviation | (°C) | Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19.70 M | 38.308 | −0.39% | 36.396 | 0.63% |

| 33.36 M | 38.392 | −0.17% | 36.294 | 0.35% |

| 50.91 M | 38.457 | Baseline | 36.167 | Baseline |

| 65.51 M | 38.460 | 0.08% | 36.172 | 0.02% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, S.; Qu, S.; Ding, J.; Mo, H.; Song, X. Feasibility Study on Reusing Recycled Premixed Multi-Material Powder in the Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process for Thermal Management Application. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16101186

Gao S, Qu S, Ding J, Mo H, Song X. Feasibility Study on Reusing Recycled Premixed Multi-Material Powder in the Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process for Thermal Management Application. Micromachines. 2025; 16(10):1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16101186

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Shiming, Shuo Qu, Junhao Ding, Haoming Mo, and Xu Song. 2025. "Feasibility Study on Reusing Recycled Premixed Multi-Material Powder in the Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process for Thermal Management Application" Micromachines 16, no. 10: 1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16101186

APA StyleGao, S., Qu, S., Ding, J., Mo, H., & Song, X. (2025). Feasibility Study on Reusing Recycled Premixed Multi-Material Powder in the Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process for Thermal Management Application. Micromachines, 16(10), 1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16101186