Influence of High-Power Laser Cleaning on Oxide Layer Formation on 304L Stainless Steel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Set-Up

2.1. Materials and Laser Set-Up

2.2. Microstructure

3. Results and Discussion

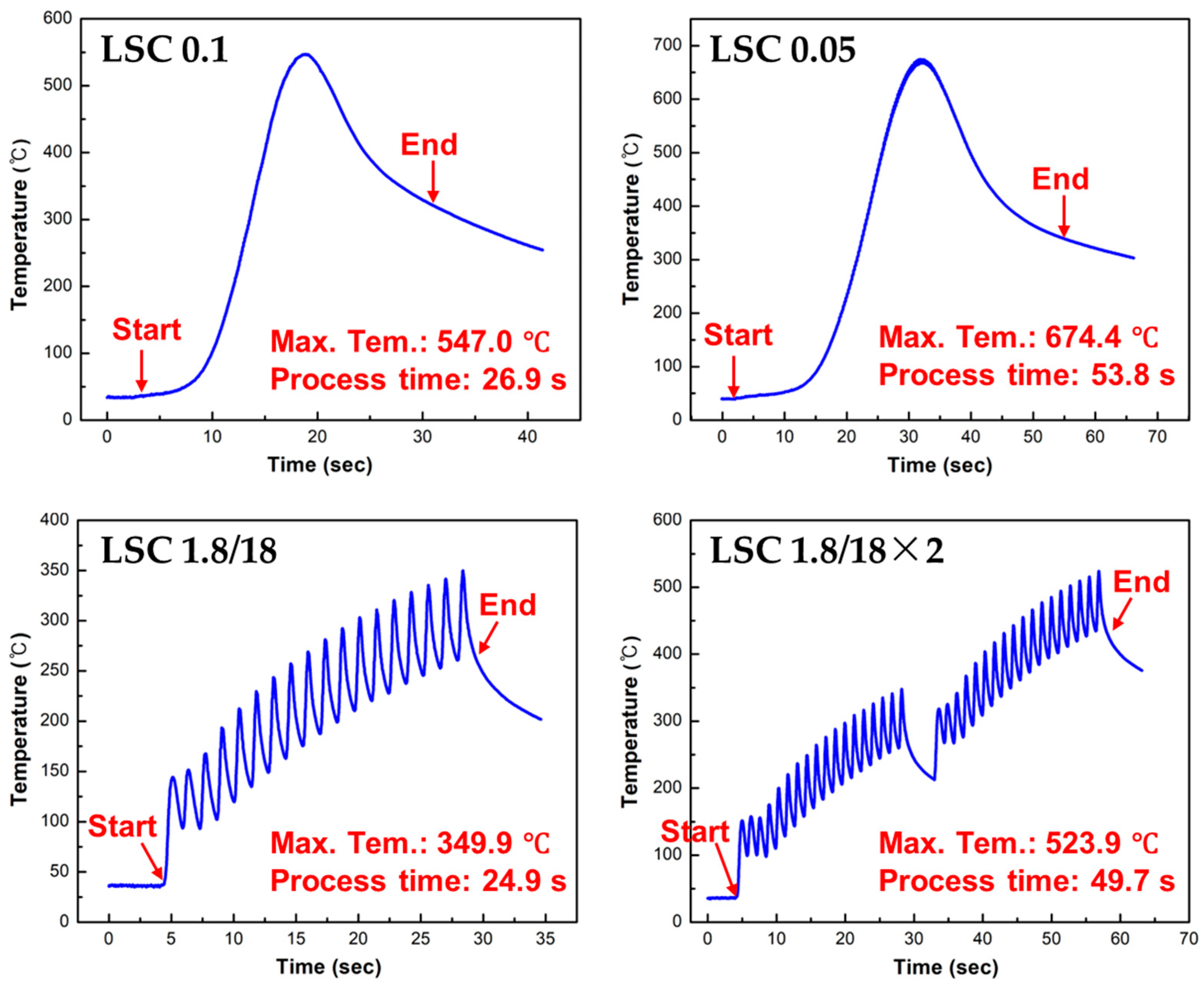

3.1. Laser Cleaning Process

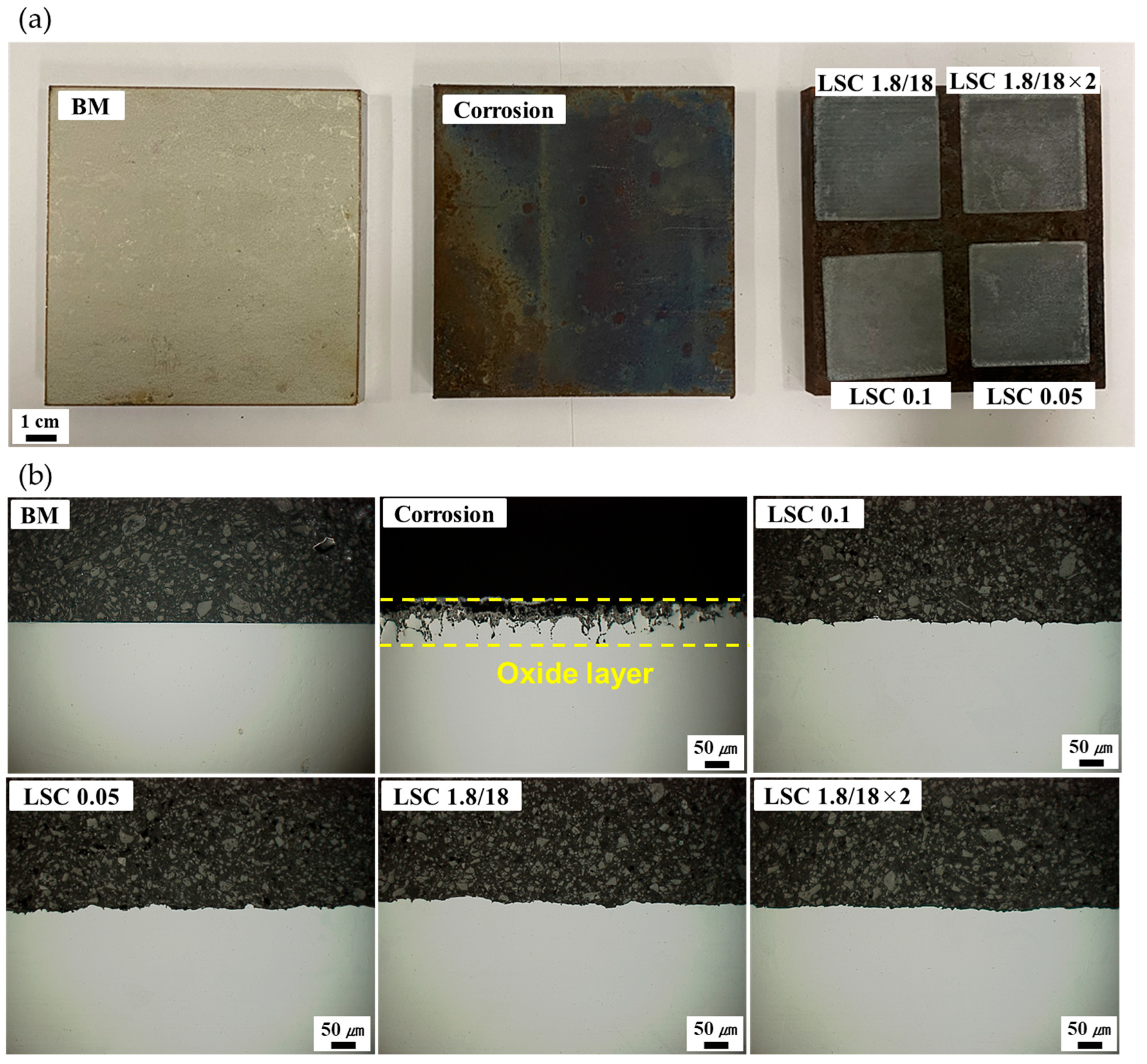

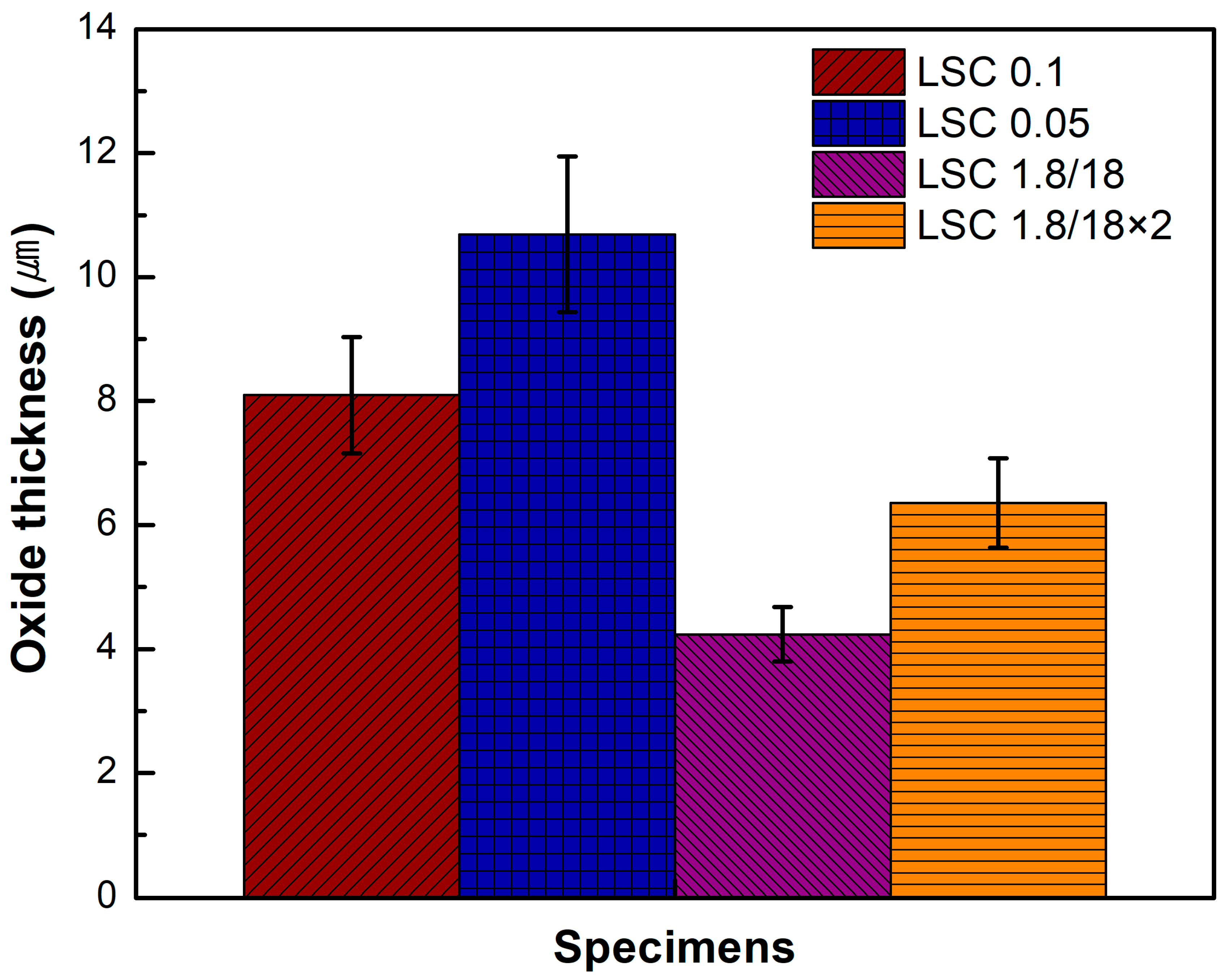

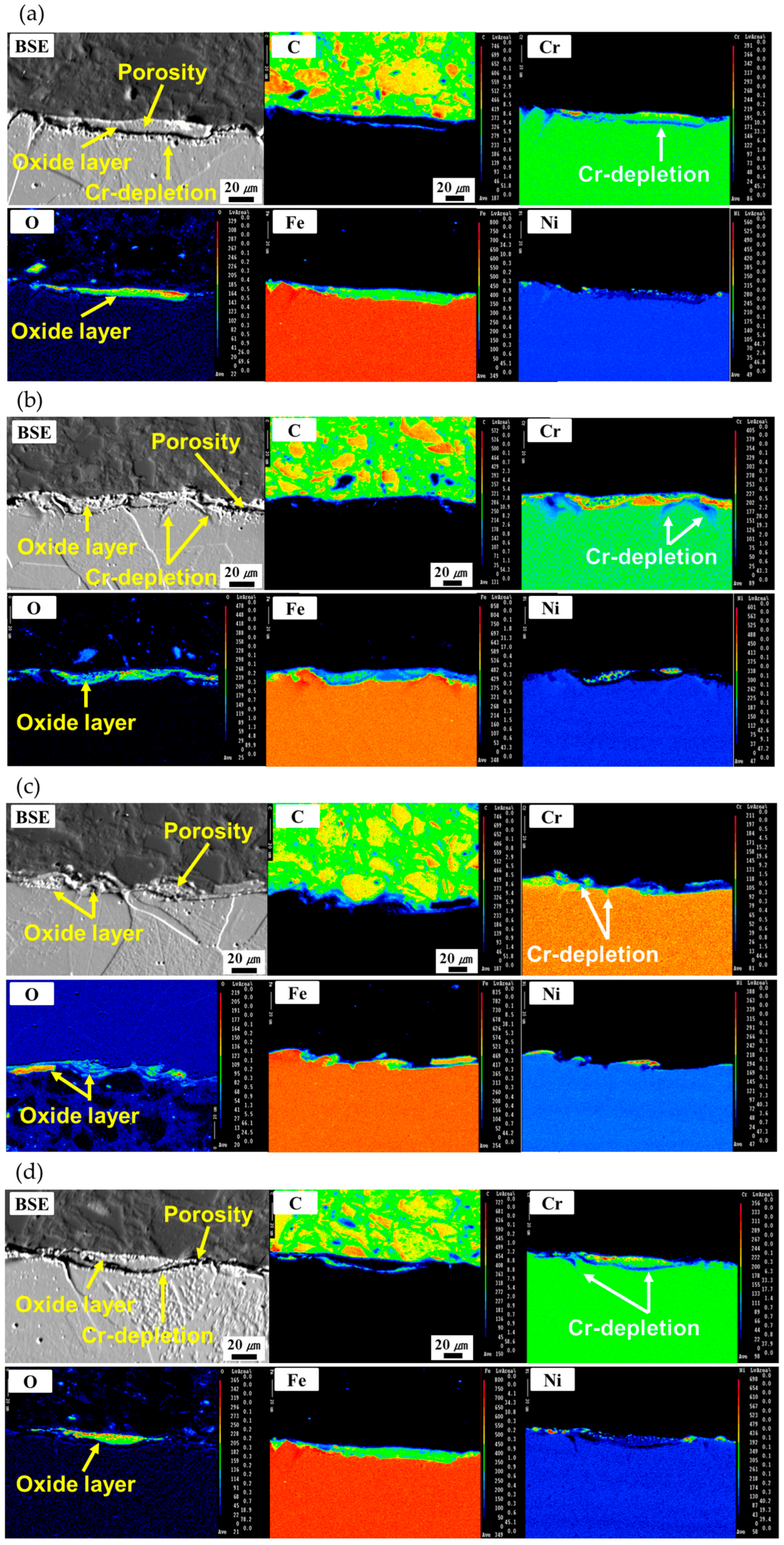

3.2. Oxide Layer Formation

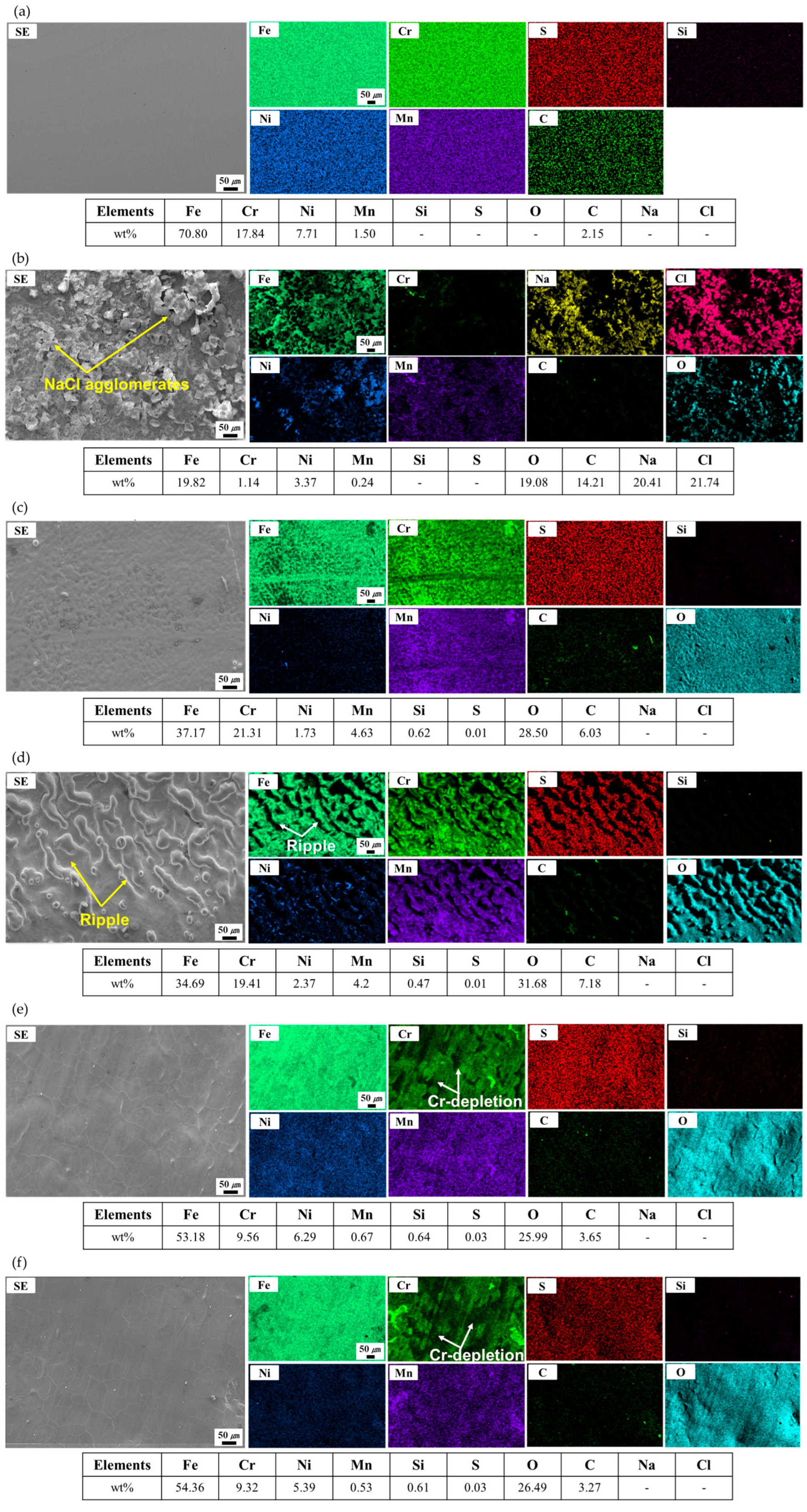

3.3. Development of Cr-Depleted Regions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SS304L | 304L stainless steel |

| LC | Laser cleaning |

| EDX | Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| EPMA | Electron probe X-ray microanalysis |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| OM | Optical microscopy |

| BM | Base metal |

| BSE | Backscattered electron |

References

- Yang, D.; Khan, T.S.; Al-Hajri, E.; Ayub, Z.H.; Ayub, A.H. Geometric optimization of shell and tube heat exchanger with interstitial twisted tapes outside the tubes applying CFD techniques. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 152, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinkle, S.J.; Was, G.S. Materials challenges in nuclear energy. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 735–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsouli, S.; Lekatou, A.G.; Kleftakis, S.; Matikas, T.E.; Dalla, P.T. Corrosion behavior of 304L stainless steel concrete reinforcement in acid rain using fly ash as corrosion inhibitor. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2018, 10, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, A.; Ramnanan, A.; Maharaj, C. Failure analysis of carbon steel tubes in a reformed gas boiler feed water preheater. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2019, 19, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luder, D.; Hundhausen, T.; Kaminsky, E.; Shor, Y.; Iddan, N.; Ariely, S.; Yalin, M. Failure analysis and metallurgical transitions in SS 304L air pipe caused by local overheating. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2016, 59, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, F.; Abi-Aad, E.; Duponchel, B.; Serre, I.P.; Ringot, S.; Langry, P.; Aboukaïs, A. Thermal ageing process at laboratory scale to evaluate the lifetime of Liquefied Natural Gas storage and loading/unloading materials. Mater. Des. 2013, 44, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.; Galao, O.; Torres, J.; Fullea, J.; Andrade, C.; Garcia, J.C.; Ruesga, J.; Cano, P. 40 years old LNG stainless steel pipeline: Characterization and mechanical behavior engineering. Fail. Anal. 2017, 79, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kina, A.Y.; Souza, V.M.; Tavares, S.S.M.; Pardal, J.M.; Souza, J.A. Microstructure and intergranular corrosion resistance evaluation of AISI 304 steel for high temperature service. Mater. Charact. 2008, 59, 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Rovere, C.A.; Castro-Rebello, M.; Kuri, S.E. Corrosion behavior analysis of an austenitic stainless steel exposed to fire. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2013, 31, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A.; Taheri, P. A Study on the Failure of AISI 304 Stainless Steel Tubes in a Gas Heater Unit. Metals 2019, 9, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A.; Anijdan, S.H.M.; Taheri, P.; Mehr, M.Y. Failure of AISI 304H stainless steel elbows in a heat exchanger. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2018, 90, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasitha, T.P.; Vanithakumari, S.C.; George, R.P.; Philip, J. Template-Free One-Step Electrodeposition Method for Fabrication of Robust Superhydrophobic Coating on Ferritic Steel with Self-Cleaning Ability and Superior Corrosion Resistance. Langmuir 2019, 35, 12665–12679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Zhu, X.; Gao, W.; Yin, H. Direct Growth of Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanofilms on Stainless Steel for Corrosion Protection. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 12024–12033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurovic, B.; Jean, E.; Papini, M.; Tangestanian, P.; Spelt, J.K. Coating removal from fiber-composites and aluminum using starch media. Wear 1999, 224, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.-K.; Chuang, T.H. Surface morphologies and erosion rates of metallic building materials after sandblasting. Wear 1999, 230, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, G.; Sofia, S.; Anandkumar, B.; Vanith-akumari, S.C.; George, R.P.; Philip, J. Graphene oxide/polyvinylpyrrolidone composite coating on 316L SS with superior antibacterial and anti-biofouling properties. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 158, 106356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multigner, M.; Frutos, E.; González-Carrasco, J.L.; Jiménez, J.A.; Marín, P.; Ibáñez, J. Influence of the sandblasting on the subsurface microstructure of 316LVM stainless steel: Implications on the magnetic and mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2009, 29, 1357–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horodek, P.; Siemek, K.; Dryzek, J.; Wróbel, M. Impact of abradant size on damaged zone of 304 AISI steel characterized by positron annihilation spectroscopy. Metall. Mater. Trans. A Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 2019, 50, 1502–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsubo, F.; Kishitake, K.; Akiyama, T.; Terasaki, T. Characterization of blasted austenitic stainless steel and its corrosion resistance. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2003, 12, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambham, K.; Sangameswaran, S.; Datar, S.R.; Kura, B. Copper slag: Optimization of productivity and consumption for cleaner production in dry abrasive blasting. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, M.R.; Susi, P. A review of engineering control technology for exposures generated during abrasive blasting operations. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2004, 1, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echt, A.; Dunn, K.H.; Mickelsen, R.L. Automated abrasive blasting equipment for use on steel structures. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2010, 15, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raykowski, A.; Hader, M.; Maragno, B.; Spelt, J.K. Blast cleaning of gas turbine components: Deposit removal and substrate deformation. Wear 2001, 249, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteini, M.; Lalli, C.; Tosini, I.; Giusti, A.; Siano, S. Laser and chemical cleaning tests for the conservation of the Porta del Paradiso by Lorenzo Ghiberti. J. Cult. Herit. 2003, 4, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obot, I.B.; Meroufel, A.; Onyeachu, I.B.; Alenazi, A.; Sorour, A.A. Corrosion inhibitors for acid cleaning of desalination heat exchangers: Progress, challenges and future perspectives. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 296, 111760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufus, A.L.; Velmurugan, S.; Sathyaseelan, V.S.; Narasimhan, S.V. Comparative study of nitrilo triacetic acid (NTA) and EDTA as formulation constituents for the chemical decontamination of primary coolant systems of nuclear power plants. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2004, 44, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, P.; Hubbard, C.; Mcphail, D.; Cummings, A. A topographical assessment and comparison of conservation cleaning treatments. J. Cult. Herit. 2003, 4, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.E.; Modise, T.S. Laser removal of loose uranium compound contamination from metal surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2007, 253, 5258–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsujjoha, M.; Agnew, S.R.; Melia, M.A.; Brooks, J.R.; Tyler, T.J.; Fitz-Gerald, J.M. Effects of laser ablation coating removal (LACR) on a steel substrate: Part 1: Surface profile, microstructure, hard-ness, and adhesion. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 281, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsujjoha, M.; Agnew, S.R.; Brooks, J.R.; Tyler, T.J.; Fitz-Gerald, J.M. Effects of laser ablation coating removal (LACR) on a steel substrate: Part 2: Residual stress and fatigue. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 281, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.J.; Baek, S.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, J.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, C. Effect of laser surface cleaning of corroded 304L stainless steel on microstructure and mechanical properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 16, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; He, G.; Chen, J.; Fang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Z. Research on cleaning mechanism of anti-erosion coating based on thermal and force effects of laser shock. Coatings 2020, 10, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; Su, X.; Yang, S.; Xu, J.; Ma, R.; Shan, D.; Guo, B. Removal mechanism of surface cleaning on TA15 titanium alloy using nanosecond pulsed laser. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 139, 106998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.P.; Hodges, V.C.; Hirschfeld, D.A.; Rodriguez, M.A.; McDonald, J.P.; Kotula, P.G. Nanosecond pulsed laser irradiation of stainless steel 304L: Oxide growth and effects on underlying metal. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2013, 222, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.K.; Adams, D.P.; Bahr, D.F.; Moody, N.R. Environmental resistance of oxide tags fabricated on 304L stainless steel via nanosecond pulsed laser irradiation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 285, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Yoo, H.J.; Park, C. Wear and corrosion behaviors of high-power laser surface-cleaned 304L stainless steel. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 168, 109640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Park, C. Investigation of airborne nanoparticles emitted during the laser cleaning process of corroded metal surface. Environ. Res. 2024, 248, 118353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements | Cr | Ni | Mn | Si | Cu |

| wt% | 18.14 | 8.604 | 1.462 | 0.386 | 0.216 |

| Elements | Mo | P | C | S | Fe |

| wt% | 0.112 | 0.031 | 0.021 | 0.002 | 71.026 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoo, H.J.; Kang, H.; Kim, Y.; Park, C. Influence of High-Power Laser Cleaning on Oxide Layer Formation on 304L Stainless Steel. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121366

Yoo HJ, Kang H, Kim Y, Park C. Influence of High-Power Laser Cleaning on Oxide Layer Formation on 304L Stainless Steel. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121366

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoo, Hyun Jong, HyeonSik Kang, Youngki Kim, and Changkyoo Park. 2025. "Influence of High-Power Laser Cleaning on Oxide Layer Formation on 304L Stainless Steel" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121366

APA StyleYoo, H. J., Kang, H., Kim, Y., & Park, C. (2025). Influence of High-Power Laser Cleaning on Oxide Layer Formation on 304L Stainless Steel. Micromachines, 16(12), 1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121366