Structure of Ribosome-Inactivating Protein from Mirabilis jalapa and Its L12-Stalk-Dependent Inhibition of Escherichia coli Ribosome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Determination of the Crystal Structure of the MAP-EQRQ Mutant

2.2. Overall Structure of MAP and Its Active Site

2.3. RNA N-Glycosylase Activities by R171 and E168 Single Mutants of MAP

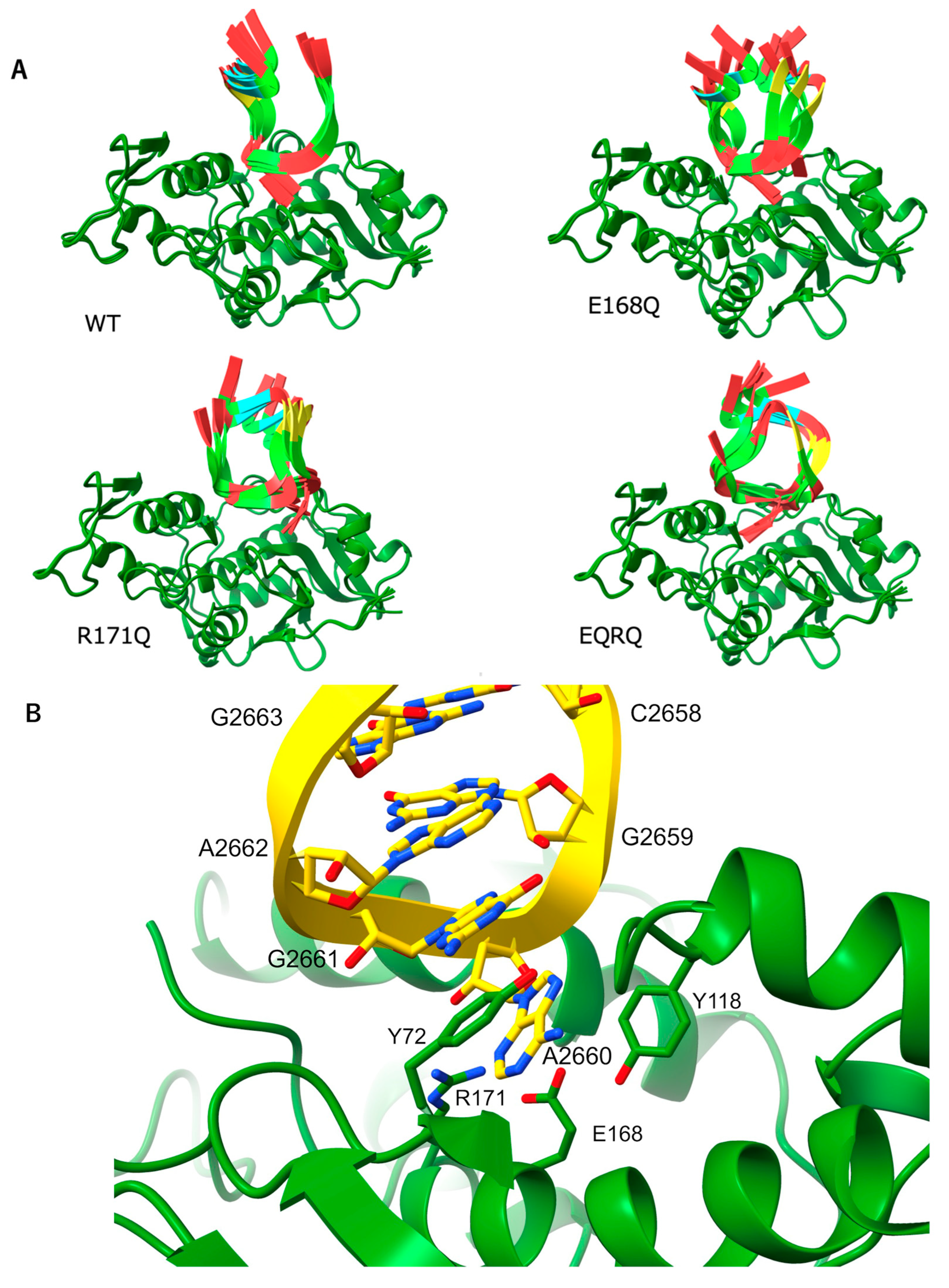

2.4. Arg171 of MAP Affects the Stability of the RNA (SRL) Binding

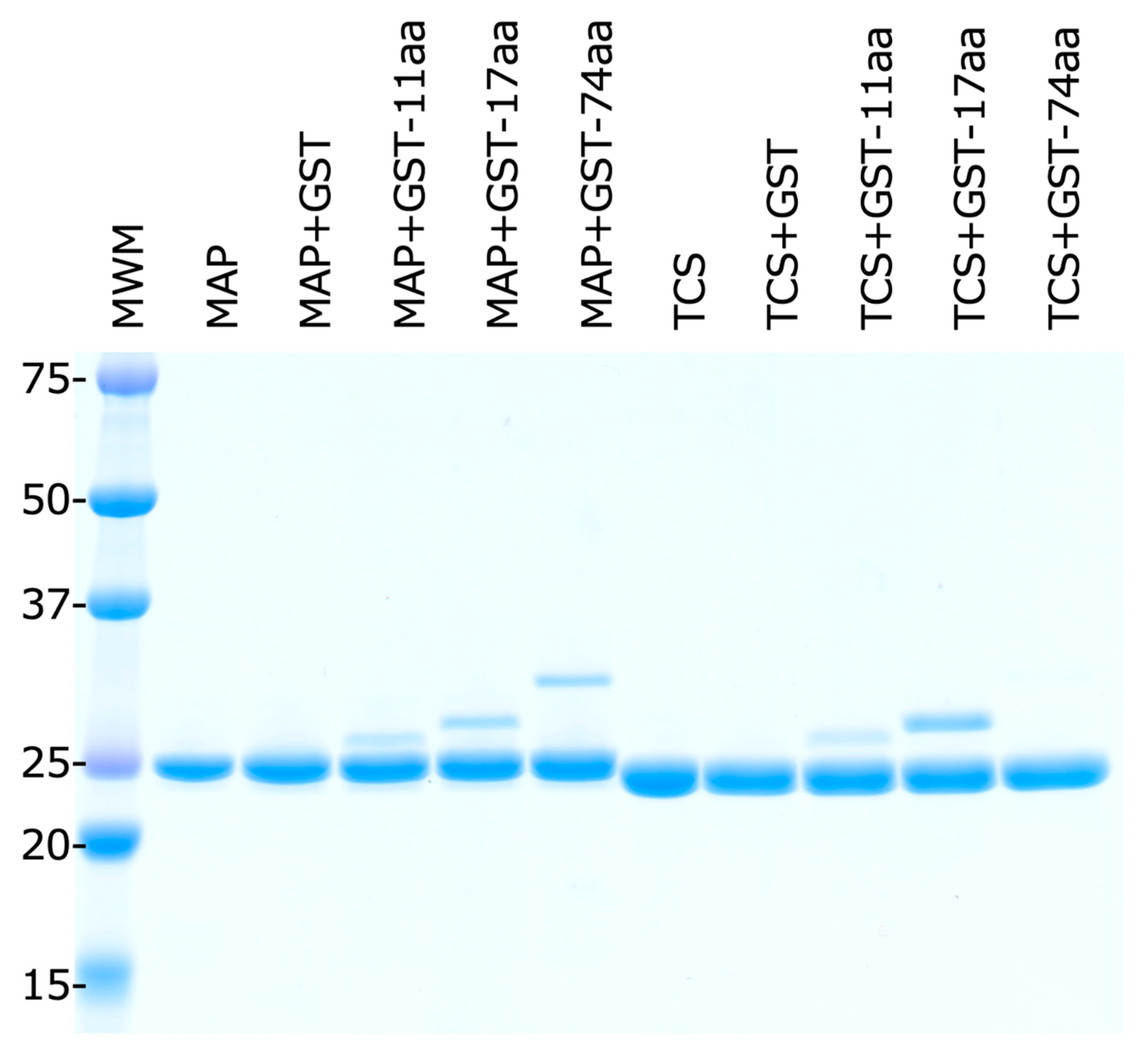

2.5. E. coli Stalk Binding Property of MAP

2.6. Structural Property in the Stalk Binding Region of MAP

3. Discussion

4. Experimental Procedure

4.1. Purification, Cloning, and Expression

4.2. RIP and GST-Stalk Peptide Binding Assay

4.3. Quantitative RT-PCR-Based RNA N-Glycosylase Assay

4.4. Crystallization, Data Collection, and Processing

4.5. Structure Determination and Refinement

4.6. Prediction of the MAP-RNA Binding Model Using AlphaFold

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stirpe, F.; Battelli, M.G. Ribosome-inactivating proteins: Progress and problems. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2006, 63, 1850–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, J.M.; Roberts, L.M.; Robertus, J.D. Ricin: Structure, mode of action, and some current applications. Faseb J. 1994, 8, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, Y.; Tsurugi, K. RNA N-glycosidase activity of ricin A-chain. Mechanism of action of the toxic lectin ricin on eukaryotic ribosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 8128–8130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, Y.; Mitsui, K.; Motizuki, M.; Tsurugi, K. The mechanism of action of ricin and related toxic lectins on eukaryotic ribosomes. The site and the characteristics of the modification in 28 S ribosomal RNA caused by the toxins. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 5908–5912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.Y.; Ng, T.B.; Wu, P.J.; Yeung, H.W. Developmental toxicity and teratogenicity of trichosanthin, a ribosome-inactivating protein, in mice. Teratog. Carcinog. Mutagen. 1993, 13, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, S.; Ikeda, T.; Imaizumi, S.; Takanami, Y.; Mikami, Y. A Potent Plant Virus Inhibitor Found in Mirabilis jalapa L. Jpn. J. Phytopathol. 1990, 56, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habuka, N.; Murakami, Y.; Noma, M.; Kudo, T.; Horikoshi, K. Amino acid sequence of Mirabilis antiviral protein, total synthesis of its gene and expression in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 6629–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habuka, N.; Akiyama, K.; Tsuge, H.; Miyano, M.; Matsumoto, T.; Noma, M. Expression and secretion of Mirabilis antiviral protein in Escherichia coli and its inhibition of in vitro eukaryotic and prokaryotic protein synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 10988–10992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habuka, N.; Miyano, M.; Kataoka, J.; Noma, M. Escherichia coli ribosome is inactivated by Mirabilis antiviral protein which cleaves the N-glycosidic bond at A2660 of 23 S ribosomal RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1991, 221, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, N.; Beckmann, R.; Cate, J.H.; Dinman, J.D.; Dragon, F.; Ellis, S.R.; Lafontaine, D.L.; Lindahl, L.; Liljas, A.; Lipton, J.M.; et al. A new system for naming ribosomal proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2014, 24, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzawa, T.; Kato, K.; Girodat, D.; Ose, T.; Kumakura, Y.; Wieden, H.J.; Uchiumi, T.; Tanaka, I.; Yao, M. The C-terminal helix of ribosomal P stalk recognizes a hydrophobic groove of elongation factor 2 in a novel fashion. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 3232–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, K.; Imai, H.; Kawamura, M.; Ishino, S.; Ishino, Y.; Ito, K.; Uchiumi, T. Switch of the interactions between the ribosomal stalk and EF1A in the GTP- and GDP-bound conformations. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helgstrand, M.; Mandava, C.S.; Mulder, F.A.; Liljas, A.; Sanyal, S.; Akke, M. The ribosomal stalk binds to translation factors IF2, EF-Tu, EF-G and RF3 via a conserved region of the L12 C-terminal domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 365, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leijonmarck, M.; Liljas, A. Structure of the C-terminal domain of the ribosomal protein L7/L12 from Escherichia coli at 1.7 A. J. Mol. Biol. 1987, 195, 555–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, J.C.; Li, X.P.; Remacha, M.; Ballesta, J.P.; Tumer, N.E. The ribosomal stalk is required for ribosome binding, depurination of the rRNA and cytotoxicity of ricin A chain in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 70, 1441–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, M.J.; Davis, S.A.; Tumer, N.E.; Li, X.P. Structural basis for the interaction of Shiga toxin 2a with a C-terminal peptide of ribosomal P stalk proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 15588–15596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczyk, A.W.; Sorzano, C.O.S.; Grela, P.; Tchorzewski, M.; Tumer, N.E.; Li, X.P. Cryo-EM structure of Shiga toxin 2 in complex with the native ribosomal P-stalk reveals residues involved in the binding interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 102795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.W.; Tang, Y.S.; Sze, S.Y.; Zhu, Z.N.; Wong, K.B.; Shaw, P.C. Crystal Structure of Ribosome-Inactivating Protein Ricin A Chain in Complex with the C-Terminal Peptide of the Ribosomal Stalk Protein P2. Toxins 2016, 8, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.K.; Wong, E.C.; Lee, K.M.; Wong, K.B. Structures of eukaryotic ribosomal stalk proteins and its complex with trichosanthin, and their implications in recruiting ribosome-inactivating proteins to the ribosomes. Toxins 2015, 7, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, Y.; Tsurugi, K. The RNA N-glycosidase activity of ricin A-chain. The characteristics of the enzymatic activity of ricin A-chain with ribosomes and with rRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 8735–8739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Too, P.H.; Ma, M.K.; Mak, A.N.; Wong, Y.T.; Tung, C.K.; Zhu, G.; Au, S.W.; Wong, K.B.; Shaw, P.C. The C-terminal fragment of the ribosomal P protein complexed to trichosanthin reveals the interaction between the ribosome-inactivating protein and the ribosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, C.; Niu, L.; Teng, M.; Li, X. Structural insights into the interaction of the ribosomal P stalk protein P2 with a type II ribosome-inactivating protein ricin. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, M.P.; Kim, Y.; Robertus, J.D. Site-directed mutagenesis of ricin A-chain and implications for the mechanism of action. Proteins 1991, 10, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Robertus, J.D. Analysis of several key active site residues of ricin A chain by mutagenesis and X-ray crystallography. Protein Eng. 1992, 5, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, F.; Higgins, D.G. Clustal Omega for making accurate alignments of many protein sequences. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouet, P.; Courcelle, E.; Stuart, D.I.; Metoz, F. ESPript: Analysis of multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics 1999, 15, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ago, H.; Kataoka, J.; Tsuge, H.; Habuka, N.; Inagaki, E.; Noma, M.; Miyano, M. X-ray structure of a pokeweed antiviral protein, coded by a new genomic clone, at 0.23 nm resolution. A model structure provides a suitable electrostatic field for substrate binding. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994, 225, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzingo, A.F.; Robertus, J.D. X-ray analysis of substrate analogs in the ricin A-chain active site. J. Mol. Biol. 1992, 227, 1136–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Liu, S.; Tang, Y.; Jin, S.; Wang, Y. Studies on crystal structures, active-centre geometry and depurinating mechanism of two ribosome-inactivating proteins. Biochem. J. 1995, 309 Pt 1, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.P.; Xia, Z.X.; Wang, Y. Crystal structure of trichosanthin-NADPH complex at 1.7 A resolution reveals active-site architecture. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1994, 1, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grela, P.; Szajwaj, M.; Horbowicz-Drozdzal, P.; Tchorzewski, M. How Ricin Damages the Ribosome. Toxins 2019, 11, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyano, M.; Appelt, K.; Arita, M.; Habuka, N.; Kataoka, J.; Ago, H.; Tsuge, H.; Noma, M.; Ashford, V.; Xuong, N. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of Mirabilis antiviral protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1992, 226, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley, M.R.; Legname, G.; Osborn, R.; Chen, Z.; Lord, J.M. Single-chain ribosome inactivating proteins from plants depurinate Escherichia coli 23S ribosomal RNA. FEBS Lett. 1991, 290, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Yusa, K.; Chu, L.O.; Yu, C.W.; Oono, M.; Miyoshi, T.; Ito, K.; Shaw, P.C.; Wong, K.B.; Uchiumi, T. Solution structure of human P1*P2 heterodimer provides insights into the role of eukaryotic stalk in recruiting the ribosome-inactivating protein trichosanthin to the ribosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 8776–8787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabsch, W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emsley, P.; Cowtan, K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004, 60, 2126–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, P.D.; Grosse-Kunstleve, R.W.; Hung, L.W.; Ioerger, T.R.; McCoy, A.J.; Moriarty, N.W.; Read, R.J.; Sacchettini, J.C.; Sauter, N.K.; Terwilliger, T.C. PHENIX: Building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002, 58, 1948–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, R.A.; MacArthur, M.W.; Moss, D.S.; Thornton, J.M. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993, 26, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, V.B.; Arendall, W.B., 3rd; Headd, J.J.; Keedy, D.A.; Immormino, R.M.; Kapral, G.J.; Murray, L.W.; Richardson, J.S.; Richardson, D.C. MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, E.C.; Goddard, T.D.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Pearson, Z.J.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MAP-EQRQ | |

|---|---|

| PDB ID | 9X2O |

| Data collection | |

| Space group | C 1 2 1 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 214.3, 60.7, 79.3 |

| β (°) | 109.0 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0000 |

| Resolution | 43.9–2.1 (2.22–2.15) |

| Rmeas | 0.300 (1.141) |

| Rpim | 0.115 (0.436) |

| CC1/2 | 0.984 (0.529) |

| I/σI | 7.4 (2.0) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.87 (99.57) |

| Redundancy | 3.4 (3.4) |

| Refinement | |

| No. reflections | 56,406 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.019/0.024 |

| No. waters | 8614 |

| B factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 18.51 |

| Ligands | 37.71 |

| Water | 26.47 |

| r.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 |

| Bond angles (Å) | 0.84 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Favored (%) | 97.38 |

| Allowed (%) | 2.62 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nishida, N.; Ninomiya, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Tanzawa, T.; Maki, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Tsuge, H.; Habuka, N. Structure of Ribosome-Inactivating Protein from Mirabilis jalapa and Its L12-Stalk-Dependent Inhibition of Escherichia coli Ribosome. Toxins 2025, 17, 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120575

Nishida N, Ninomiya Y, Yoshida T, Tanzawa T, Maki Y, Yoshida H, Tsuge H, Habuka N. Structure of Ribosome-Inactivating Protein from Mirabilis jalapa and Its L12-Stalk-Dependent Inhibition of Escherichia coli Ribosome. Toxins. 2025; 17(12):575. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120575

Chicago/Turabian StyleNishida, Nanami, Yuki Ninomiya, Toru Yoshida, Takehito Tanzawa, Yasushi Maki, Hideji Yoshida, Hideaki Tsuge, and Noriyuki Habuka. 2025. "Structure of Ribosome-Inactivating Protein from Mirabilis jalapa and Its L12-Stalk-Dependent Inhibition of Escherichia coli Ribosome" Toxins 17, no. 12: 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120575

APA StyleNishida, N., Ninomiya, Y., Yoshida, T., Tanzawa, T., Maki, Y., Yoshida, H., Tsuge, H., & Habuka, N. (2025). Structure of Ribosome-Inactivating Protein from Mirabilis jalapa and Its L12-Stalk-Dependent Inhibition of Escherichia coli Ribosome. Toxins, 17(12), 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins17120575