Polyphenol Compound as a Transcription Factor Inhibitor

Abstract

:1. Introduction

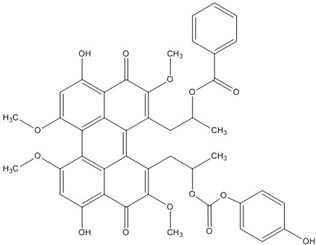

2. Symmetric Polyphenols

| Name | Structure | IC50 (mM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP-1 | Myc/Max | β-catenin | ||

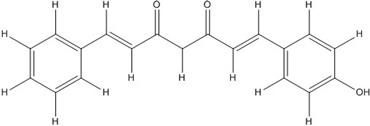

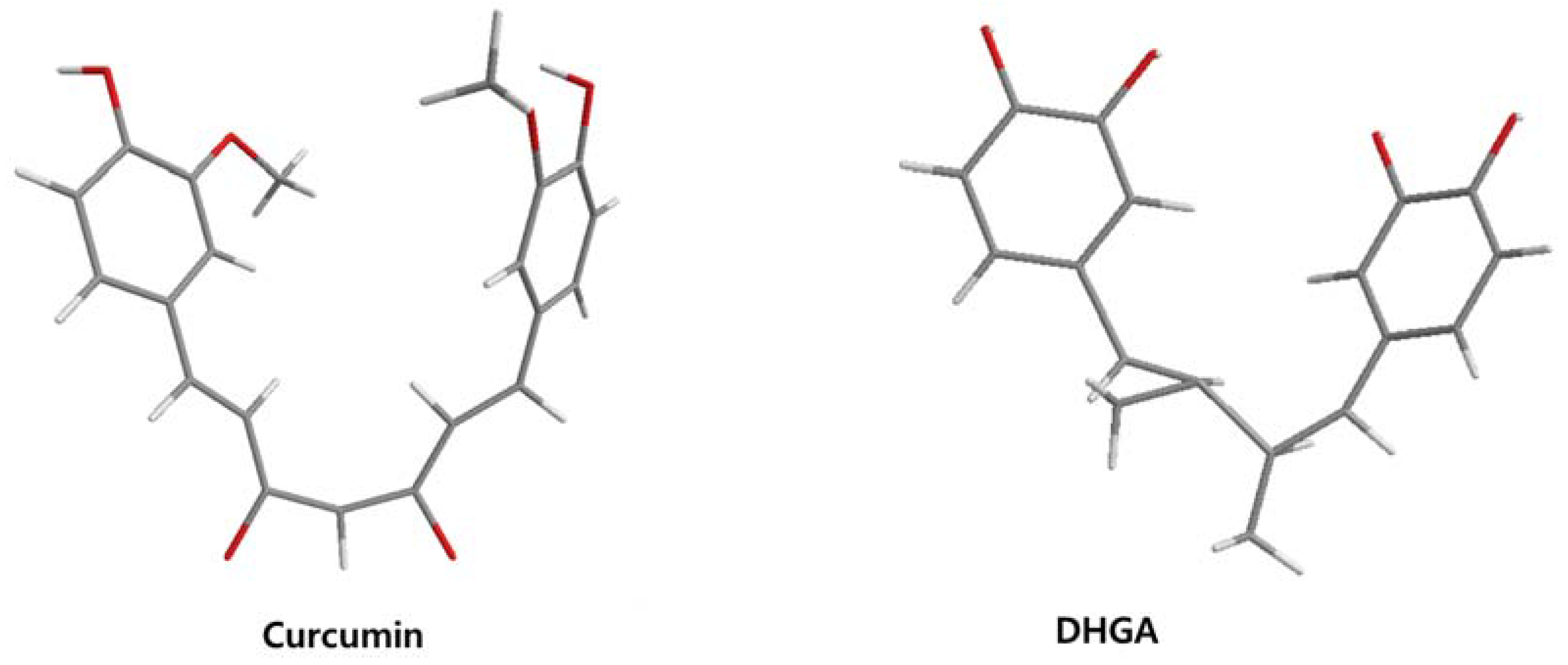

| DHGA |  | 8.4 [45] | ||

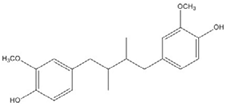

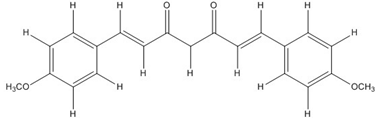

| NDGA |  | 0.34 [45] | 8 [49] | 0.01 [48] |

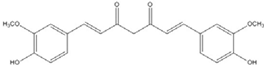

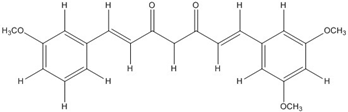

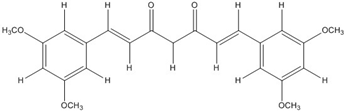

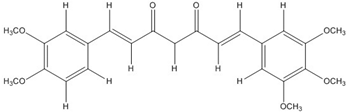

| Curcumin |  | 0.28 [45] | 0.6 [49] | 0.012 [46] |

| Asarinin |  | 0.3 [49] | ||

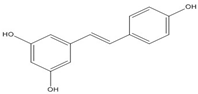

| Resveratrol |  | 0.03 [50,51] | ||

| T-5224 |  | 2 [52] | ||

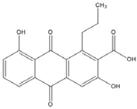

| Anthraquinone |  | 0.1 [53] | ||

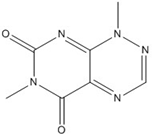

| Name | Structure | IC50 (mM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activator Protein-1 | Myc/Max | β-Catenin | ||

| Curcumin |  | 0.28 [44] | 0.6 [49] | 0.012 [54] |

| CHC001 |  | 5.4 [44] | ||

| CHC002 |  | 6.7 [44] | ||

| CHC003 |  | 3.9 [44] | ||

| CHC004 |  | 1.6 [44] | 0.082 [49] | |

| CHC005 |  | 1.8 [44] | 0.4 [49] | |

| CHC006 |  | No inhibition [44] | ||

| CHC007 |  | 0.38 [44] | 0.06 [54] | |

| CHC008 |  | 1.4 [44] | 0.16 [49] | |

| CHC009 |  | 0.64 [44] | ||

| CHC011 |  | 0.3 [44] | 0.43 [49] | |

| BJC004 |  | No inhibition [44] | ||

| BJC005 |  | 0.0054 [44] |

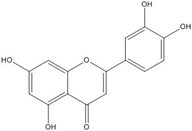

3. Flavonoids

| Name | Structure | AP-1 | IC50 (mM) Myc/Max | β-catenin | NF-κB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

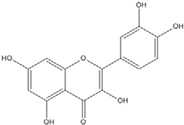

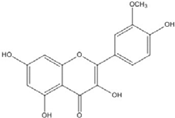

| Quercetin |  | 0.0076 [67] | 0.03 [69] | ||

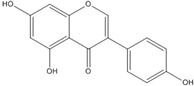

| Genistein |  | 0.01 [66] | |||

| Kaempferol |  | 0.0029 [49] | 2 [49] | 0.0016 [66] | 0.003 [70] |

| Isorhamnetin |  | 0.0062 [66] | |||

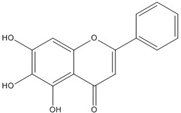

| Baicalein |  | 0.00026 [66] | |||

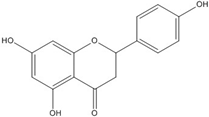

| Naringenin |  | No inhibition [71] | |||

| Epigallo catechingallate |  | No inhibition [49] | |||

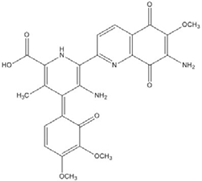

| Sterptonigrin |  | 0.005 [72] | |||

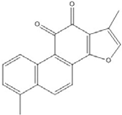

| Tanshinone I |  | 2.6 [49] | |||

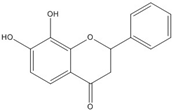

| 7,8-dihydroxy flavanone |  | 1.8 [49] | |||

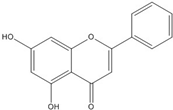

| Chrysin |  | 0.2 [53] | |||

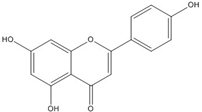

| Apigenin |  | 0.1 [53] | ~0.002 [53] | ||

| Luteolin |  | 0.1 [53] | ~0.002 [53] | ||

| Flavanone |  | No inhibition [71] | >0.003 [53] |

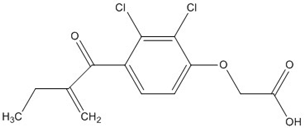

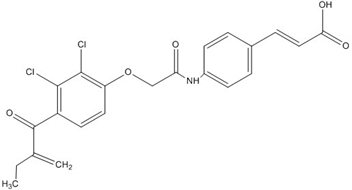

4. Non Flavonoid Polyphenol β-catenin Inhibitors

| Compound | Structure | β-Catenin IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| PKF118-744 |  | 2.4 [73,74,75,76] |

| CGP049090 |  | 8.7 [73,74,75,76] |

| PKF118-310 |  | 0.8 [73,74,75,76] |

| ZTM00990 |  | 0.64 [73,74,75,76] |

| BC21 |  | Not Determined [73,77] |

| Ethacrynic acid |  | ~70 [73,78,79] |

| Ethacrynic acid derivative |  | ~5 [73,79] |

| PKF115-584 |  | 3.2 [73,74,75,76] |

| PNU-74654 |  | Not Determined [73,74,75,76] |

5. Conclusions

References

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: Food sources and bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manach, C.; Williamson, G.; Morand, C.; Scalbert, A.; Rémésy, C. Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. I. Review of 97 bioavailability studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 230S–242S. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El Gharras, H. Polyphenols: Food sources, properties and applications—A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2009, 44, 2512–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, T.; Franza, B.R., Jr. Fos and Jun: The AP-1 connection. Cell 1988, 55, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P.F.; McKnight, S.L. Eukaryotic transcriptional regulatory proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1989, 58, 799–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, P.J.; Tjian, R. Transcriptional regulation in mammalian cells by sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. Science 1989, 245, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.; Mitchell, P.; Tjian, R. Purified transcription factor AP-1 interacts with TPA-inducible enhancer elements. Cell 1987, 49, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, P.; Imagawa, M.; Chiu, R.; Stein, B.; Imbra, R.J.; Rahmsdorf, H.J.; Jonat, C.; Herrlich, P.; Karin, M. Phorbol ester-inducible genes contain a common cis element recognized by a TPA-modulated trans-acting factor. Cell 1987, 49, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, J.; Nau, M.; Birrer, M.; Thomas, F.; Gazdar, A.; Minna, J. Constitutive expression of multiple mRNA forms of the c-jun oncogene in human lung cancer cell lines. Proc. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 1988, 1808, 455–462. [Google Scholar]

- Bossy-Wetzel, E.; Bravo, R.; Hanahan, D. Transcription factors junB and c-jun are selectively up-regulated and functionally implicated in fibrosarcoma development. Genes Dev. 1992, 6, 2340–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattei, M.G.; Simon-Chazottes, D.; Hirai, S.; Ryseck, R.P.; Galcheva-Gargova, Z.; Guénet, J.L.; Mattei, J.F.; Bravo, R.; Yaniv, M. Chromosomal localization of the three members of the jun proto-oncogene family in mouse and man. Oncogene 1990, 5, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schutte, J.; Minna, J.D.; Birrer, M.J. Deregulated expression of human c-jun transforms primary rat embryo cells in cooperation with an activated c-Ha-ras gene and transforms Rat-1a cells as a single gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 2257–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Burg, B.; van Selm-Miltenburg, A.J.P.; de Laat, S.W.; van Zoolen, F.J.J. Direct effects of estrogen on c-fos and c-myc protooncogene expression and cellular proliferation in human mammary breast cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1989, 64, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baichwal, V.R.; Tjian, R. Control of c-Jun activity by interaction of a cell-specific inhibitor with regulatory domain delta: Differences between v- and c-Jun. Cell 1990, 63, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, A.E.; Pontén, I.; Cotgreave, I.; Jernström, B. Inhibitory effects on the DNA binding of AP-1 transcription factor to an AP-1 binding site modified by benzo[α]pyrene 7,8-dihydrodiol 9,10-epoxide diastereomers. Carcinogenesis 1996, 17, 1963–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalla-Favera, R.; Wong-Staal, F.; Gallo, R.C. Onc gene amplification in promyelocytic leukaemia cell line HL-60 and primary leukaemic cells of the same patient. Nature 1982, 299, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magrath, I. The pathogenesis of Burkitt’s lymphoma. Adv. Cancer Res. 1990, 55, 133–270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Payne, G.S.; Bishop, J.M.; Varmus, H.E. Multiple arrangements of viral DNA and an activated host oncogene in bursal lymphomas. Nature 1982, 295, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neil, J.C.; Forrest, D.; Doggett, D.L.; Mullins, J.I. The role of feline leukaemia virus in naturally occurring leukaemias. Cancer Surviv. 1987, 6, 117–137. [Google Scholar]

- Eilers, M.; Schirm, S.; Bishop, J.M. The MYC protein activates transcription of the alpha-prothymosin gene. EMBO J. 1991, 10, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Penn, L.J.; Laufer, E.M.; Land, H. C-MYC: Evidence for multiple regulatory functions. Semin. Cancer Biol. 1990, 1, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Land, H.; Parada, L.F.; Weinberg, R.A. Tumorigenic conversion of primary embryo fibroblasts requires at least two cooperating oncogenes. Nature 1983, 304, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, J.A.; Cole, M.D. Constitutive c-myc oncogene expression blocks mouse erythroleukaemia cell differentiation but not commitment. Nature 1986, 320, 760–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miner, J.H.; Wold, B.J. c-myc inhibition of MyoD and myogenin-initiated myogenic differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991, 11, 2842–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, C.D.; Nau, M.M.; Carney, D.N.; Gazdar, A.F.; Minna, J.D. Amplification and expression of the c-myc oncogene in human lung cancer cell lines. Nature 1983, 306, 194–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escot, C.; Theillet, C.; Lidereau, R.; Spyratos, F.; Champeme, M.H.; Gest, J.; Callahan, R. Genetic alteration of the c-myc protooncogene (MYC) in human primary breast carcinomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 4834–4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinion, S.B.; Kennedy, J.H.; Miller, R.W.; MacLean, A.B. Oncogene expression in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive cancer of cervix. Lancet 1991, 337, 819–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Yoo, H.S.; Lee, K.T.; Goh, S.H.; Jung, J.S.; Oh, S.W.; Baba, M.; Yasuda, T.; Matsubara, K.; Nagai, H.; et al. Detection of genetic alterations in the human gastric cancer cell lines by two-dimensional analysis of genomic DNA. Int. J. Oncol. 2000, 17, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgenbesser, S.D.; DePinho, R.A. Use of transgenic mice to study myc family gene function in normal mammalian development and in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 1994, 5, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pelengaris, S.; Rudolph, B.; Littlewood, T. Action of Myc in vivo—Proliferation and apoptosis. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2000, 10, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullions, L.C.; Levine, A.J. The role of beta-catenin in cell adhesion, signal transduction, and cancer. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 1998, 10, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, P.J.; Sparks, A.B.; Korinek, V.; Barker, N.; Clevers, H.; Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. Activation of b-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in β-catenin or APC. Science 1997, 275, 1787–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujie, H.; Moriya, K.; Shintani, Y.; Tsutsumi, T.; Takayama, T.; Makuuchi, M.; Kimura, S.; Koike, K. Frequent β-catenin aberration in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Res. 2001, 20, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, D.K.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, H.S.; Kang, Y.H.; Yang, H.K.; Kim, W.H. Altered expression and mutation of β-catenin gene in gastric carcinomas and cell lines. Int. J. Cancer 2001, 95, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, S.M.; Zilz, N.; Beazer-Barclay, Y.; Bryan, T.M.; Hamilton, S.R.; Thibodeau, S.N.; Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. APC mutations occur early during colorectal tumorigenesis. Nature 1992, 359, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatsuru, S.; Yanagisawa, A.; Ichii, S.; Tahara, E.; Kato, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Horii, A. Somatic mutation of the APC gene in gastric cancer: Frequent mutations in very well differentiated adenocarcinoma and signet-ring cell carcinoma. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1992, 1, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clements, W.M.; Wang, J.; Sarnaik, A.; Kim, O.J.; MacDonald, J.; Fenoglio-Preiser, C.; Groden, J.; Lowy, A.M. β-catenin mutation is a frequent cause of Wnt pathway activation in gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 3503–3506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tian, B.; Brasier, A.R. Identification of a nuclear factor κB-dependent gene network. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 2003, 58, 95–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karin, M.; Cao, Y.; Greten, F.R.; Li, Z.W. NF-κB in cancer: From innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mees, C.; Nemunaitis, J.; Senzer, N. Transcription factors: Their potential as targets for an individualized therapeutic approach to cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009, 16, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, H.Q.; Abbruzzese, J.L.; Lin, E.; Wang, L.; Zheng, L.; Xie, K. NF-κB activity blockade impairs the angiogenic potential of human pancreatic cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer 2004, 108, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brickman, J.M.; Adam, M.; Ptashne, M. Interactions between an HMG-1 protein and members of the Rel family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 10679–10683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campisi, J. Cellular senescence as a tumor suppressor mechanism. Trends Cell Biol. 2001, 11, S27–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahm, E.R.; Cheon, G.; Lee, J.; Kim, B.; Park, C.; Yang, C.H. New and known symmetrical curcumin derivatives inhibit the formation of Fos-Jun-DNA complex. Cancer Lett. 2002, 184, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, D.K.; Yang, C.H. Inhibition of fos-jun-DNA complex formation by dihydroguaiaretic acid and in vitro cytotoxic effects on cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 1998, 127, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahm, E.R.; Gho, Y.S.; Park, S.; Park, C.; Kim, K.W.; Yang, C.H. Synthetic curcumin analogs inhibit activator protein-1 transcription and tumor-induced angiogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 321, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.K.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.G.; Gwon, H.J.; Moon, E.Y.; Hwang, H.S.; Seong, S.K.; Lee, M.; Lim, M.J.; Sung, H.J.; et al. Momordins inhibit both AP-1 function and cell proliferation. Anticancer Res. 1998, 18, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Lee, J. Inhibitory effect of nordihydroguaiaretic acid on β-catenin/Tcf signalling in β-catenin-activated cells. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2011, 29, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S. Studies on the Inhibitory Mechanism of the Dimeric Forms of Transcription Activators. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, R.; Hebbar, V.; Kim, D.W.; Mandlekar, S.; Pezzuto, J.M.; Kong, A.N. Resveratrol inhibits phorbol ester and UV-induced activator protein 1 activation by interfering with mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 60, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goto, M.; Masegi, M.; Yamauchi, T.; Chiba, K.; Kuboi, Y.; Harada, K.; Naruse, N. K1115 A, a new anthraquinone derivative that inhibits the binding of activator protein-1 (AP-1) to its recognition sites. I. Biological. activities. J. Antibiot. 1998, 51, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aikawa, Y.; Morimoto, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Chaki, H.; Hashiramoto, A.; Narita, H.; Hirono, S.; Shiozawa, S. Treatment of arthritis with a selective inhibitor of c-Fos/activator protein-1. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, J.L.; Chauhan, J.; Jung, K.Y.; Chen, L.; Prochownik, E.V.; Fletcher, S. Small-molecule inhibitors of dimeric transcription factors: Antagonism of protein–protein and protein–DNA interactions. Med. Chem. Commun. 2012, 3, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Hahm, E.R.; Park, S.; Kim, H.K.; Yang, C.H. The inhibitory mechanism of curcumin and its derivative against beta-catenin/Tcf signaling. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579, 2965–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, A.S.; Marlow, B.P.; Gupta, N.; Narayan, S. Beta-catenin-mediated transactivation and cell-cell adhesion pathways are important in curcumin (diferuylmethane)-induced growth arrest and apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Oncogene 2002, 21, 8414–8427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, N.N.; Carothers, A.M.; Grunberger, D.; Bilinski, R.T.; Churchill, M.R.; Martucci, C.; Newmark, H.L.; Bertagnolli, M.M. Plant phenolics decrease intestinal tumors in an animal model of familial adenomatous polyposis. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amado, N.G.; Fonseca, B.F.; Cerqueira, D.M.; Neto, V.M.; Abreu, J.G. Flavonoids: Potential Wnt/beta-catenin signaling modulators in cancer. Life Sci. 2011, 89, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, D.H.; Sussman, D.J.; Seldin, D.C. Endogenous protein kinase CK2 participates in Wnt signaling in mammary epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 23790–23797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landesman-Bollag, E.; Song, D.H.; Romieu-Mourez, R.; Sussman, D.J.; Cardiff, R.D.; Sonenshein, G.E.; Seldin, D.C. Protein kinase CK2: Signaling and tumorigenesis in the mammary gland. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2001, 227, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Zhang, X.; Rieger-Christ, K.M.; Summerhayes, I.C.; Wazer, D.E.; Paulson, K.E.; Yee, A.S. Suppression of Wnt signaling by the green tea compound (−)−epigallocatechin 3-gallate (EGCG) in invasive breast cancer cells. Requirement of the transcriptional repressor HBP1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 10865–10875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dashwood, W.M.; Orner, G.A.; Dashwood, R.H. Inhibition of beta-catenin/Tcf activity by white tea, green tea, and epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG): Minor contribution of H2O2 at physiologically relevant EGCG concentrations. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 296, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlke, G.; Ngiewih, Y.; Kern, M.; Jakobs, S.; Marko, D.; Eisenbrand, G. Impact of quercetin and EGCG on key elements of the Wnt pathway in human colon carcinoma cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 7075–7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Xu, Z.; Hung, M.S.; Lin, Y.C.; Wang, T.; Gong, M.; Zhi, X.; Jablon, D.M.; You, L. Promoter demethylation of WIF-1 by epigallocatechin-3-gallate in lung cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2009, 29, 2025–2030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mount, J.G.; Muzylak, M.; Allen, S.; Althnaian, T.; McGonnell, I.M.; Price, J.S. Evidence that the canonical Wnt signalling pathway regulates deer antler regeneration. Dev. Dyn. 2006, 235, 1390–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, F.H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Kong, D. Cellular signaling perturbation by natural products. Cell Signal. 2009, 21, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Choi, J. Inhibition of beta-catenin/Tcf signaling by flavonoids. J. Cell. Biochem. 2010, 110, 1376–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.H.; Chang, J.Y.; Hahm, E.R.; Park, S.; Kim, H.K.; Yang, C.H. Quercetin, a potent inhibitor against beta-catenin/Tcf signaling in SW480 colon cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 328, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.H.; Hahm, E.R.; Lee, J.H.; Jung, K.C.; Yang, C.H. Inhibition of beta-catenin-mediated transactivation by flavanone in AGS gastric cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 331, 1222–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, Y.D.; Choi, C.H.; Bark, H.; Son, H.Y.; Park, H.H.; Lee, S.; Park, J.W.; Park, E.K.; Shin, H.I.; Kim, S.H.; et al. Quercetin inhibits expression of inflammatory cytokines through attenuation of NF-κB and p38 MAPK in HMC-1 human mast cell line. Inflamm. Res. 2007, 56, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.C.; Chow, M.P.; Huang, W.C.; Lin, Y.C.; Chang, Y.J. Flavonoids inhibit tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced up-regulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in respiratory epithelial cells through activator protein-1 and nuclear factor-κB: Structure-activity relationships. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004, 66, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Park, C.H.; Jung, K.C.; Rhee, H.S.; Yang, C.H. Negative regulation of β-catenin/Tcf signaling by naringenin in AGS gastric cancer cell. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 335, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Chun, S. Streptonigrin inhibits β-Catenin/Tcf signaling and shows cytotoxicity in β-catenin-activated cells. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1810, 1340–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voronkov, A.; Krauss, S. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and small molecule inhibitors. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 634–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepourcelet, M.; Chen, Y.N.; France, D.S.; Lubecka, B.; Matulewicz, L.; Maniakowski, Z.; Polaniak, R.; Birkner, E.; Rzeszowska-Wolny, J. Small-molecule antagonists of the oncogenic Tcf/β-catenin protein complex. Cancer Lett. 2004, 5, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, N.; Clevers, H. Mining the Wnt pathway for cancer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2006, 5, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trosset, J.Y.; Dalvit, C.; Knapp, S.; Fasolini, M.; Veronesi, M.; Mantegani, S.; Gianellini, L.M.; Catana, C.; Sundström, M.; Stouten, P.F.; et al. Inhibition of protein-protein interactions: The discovery of druglike β-catenin inhibitors by combining virtual and biophysical screening. Proteins 2006, 64, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, W.; Han, X.; Yan, M.; Xu, Y.; Duggineni, S.; Lin, N.; Luo, G.; Li, Y.M.; Han, X.; Huang, Z.; et al. Structure-based discovery of a novel inhibitor targeting the β-catenin/Tcf4 interaction. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.; Liu, J.X.; Endo, T.; Zhou, H.; Yao, S.; Willert, K.; Schmidt-Wolf, I.G.; Kipps, T.J.; Carson, D.A. Ethacrynic acid exhibits selective toxicity to chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells by inhibition of the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e8294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, G.; Lu, D.; Yao, S.; Wu, C.C.; Liu, J.X.; Carson, D.A.; Cottam, H.B. Amide derivatives of ethacrynic acid: Synthesis and evaluation as antagonists of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and CLL cell survival. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 606–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, I.S.; Fernandes, P.A.; Ramos, M.J. Hot spots—A review of the protein-protein interface determinant amino-acid residues. Proteins 2007, 68, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, L.; Jernigan, R.L.; Covell, D.G. A role for surface hydrophobicity in protein-protein recognition. Protein Sci. 1994, 3, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, N.; Lewis, M. Calculation of the free energy of association for protein complexes. Protein Sci. 1992, 1, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janin, J.; Bahadur, R.P.; Chakrabarti, P. Protein-protein interaction and quaternary structure. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2008, 41, 133–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Archivio, M.; Filesi, C.; Varì, R.; Scazzocchio, B.; Masella, R. Bioavailability of the Polyphenols: Status and Controversies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 1321–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, S. Polyphenol Compound as a Transcription Factor Inhibitor. Nutrients 2015, 7, 8987-9004. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7115445

Park S. Polyphenol Compound as a Transcription Factor Inhibitor. Nutrients. 2015; 7(11):8987-9004. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7115445

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Seyeon. 2015. "Polyphenol Compound as a Transcription Factor Inhibitor" Nutrients 7, no. 11: 8987-9004. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7115445