Driving Sustainable Entrepreneurship Through AI and Knowledge Management: Evidence from SMEs in Emerging Economies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. AI Capabilities

2.2. Knowledge Management

2.3. Sustainable Entrepreneurship

2.4. Entrepreneurial Orientation

2.5. Government Policy Support

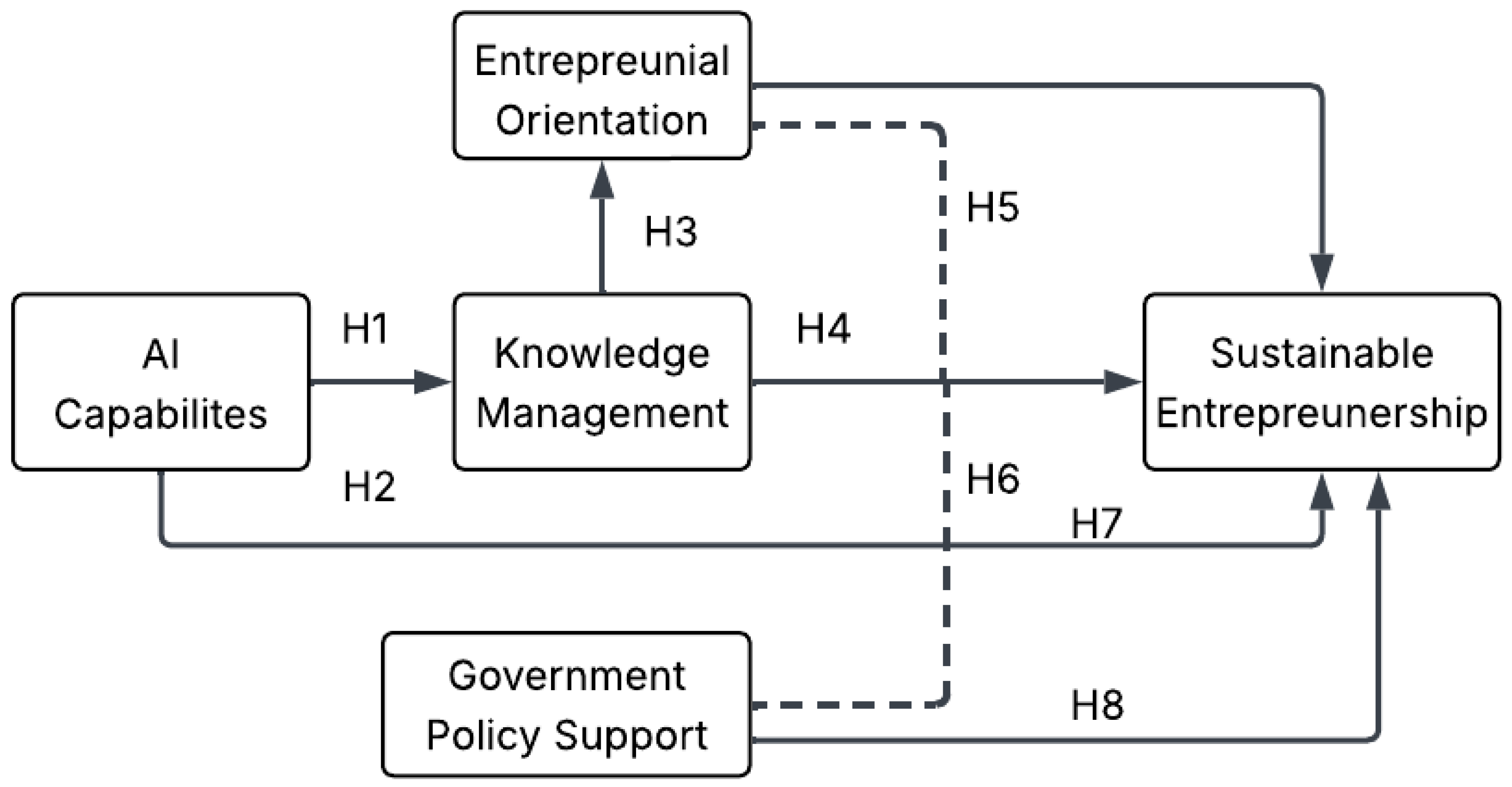

2.6. Model Constructs, Theoretical Underpinnings, and Research Hypotheses

3. Formulation of Hypotheses

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Design and Approach

4.2. Research Context

4.3. Sampling and Data Collection

4.4. Measurement of Constructs

4.5. Data Analysis Procedure

4.6. Ethical Considerations

4.7. Methodological Rigor

4.8. Reporting Standards

5. Data Analysis and Interpretation

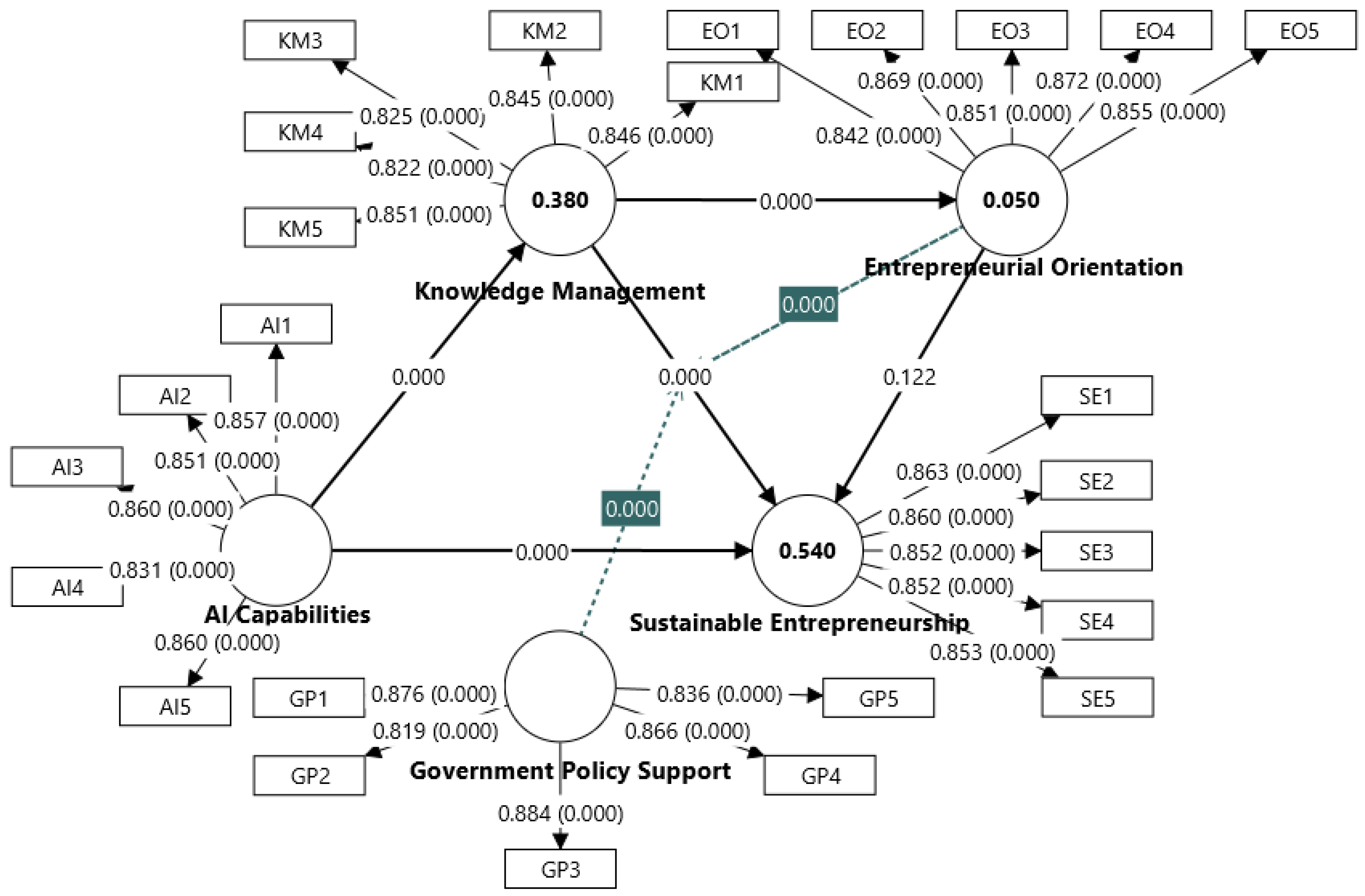

5.1. Assessment of Model

5.1.1. Measurement Model Assessment

5.1.2. Overall Model Fit and Explanatory Power

5.1.3. Hypothesis Testing and Path Relationships

5.1.4. Summary of Hypothesis Testing Results

5.2. Mechanism and Analytical Rigor

6. Discussion

6.1. AI Is an Enabling Force, Rather than a Panacea to Sustainability

6.2. The Conversion Engine Is Knowledge Management

6.3. EO and GPS: Situational Boundary Conditions

7. Conclusions

7.1. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

7.2. Final Remark

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| Abbreviation | Full Form | Context/Usage in Study |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence | Represents digital tools and capabilities that support sustainability decision-making and innovation. |

| KM | Knowledge Management | Organizational processes for acquiring, sharing, storing, and applying sustainability-related knowledge. |

| SE | Sustainable Entrepreneurship | Triple bottom line–oriented entrepreneurship integrating economic, environmental, and social value. |

| EO | Entrepreneurial Orientation | Organizational strategic posture characterized by innovativeness, proactiveness, and calculated risk-taking. |

| GPS | Government Policy Support | Institutional enablers such as regulations, incentives, and programs influencing SME sustainability performance. |

| SME | Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises | The primary context of the study, aligned with Vision 2030 and SDG progress. |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals | United Nations’ global agenda guiding sustainability integration in business. |

| DCT | Dynamic Capabilities Theory | Theoretical foundation explaining how firms adapt and reconfigure resources in changing environments. |

| KBV | Knowledge-Based View | Theoretical lens emphasizing knowledge as the core strategic resource enabling sustainability outcomes. |

| TBL | Triple Bottom Line | Sustainability measurement framework covering economic, environmental, and social performance. |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling | Analytical technique used to test the structural model and hypotheses. |

| IPMA | Importance–Performance Map Analysis | Advanced PLS method used to assess priority areas for managerial action. |

| PLS-POS | Prediction-Oriented Segmentation | Method used to identify unobserved heterogeneity within SME groups. |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted | Measure of convergent validity in construct reliability assessment. |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor | Multicollinearity diagnostic for structural relationships. |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination | Indicates explanatory power of the model for endogenous constructs. |

| Q2 | Predictive Relevance Statistic | Assesses predictive accuracy of constructs in PLS-SEM. |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual | Model fit indicator assessing overall goodness of fit. |

| NFI | Normed Fit Index | Indicator of comparative model fit quality. |

| DCT | Dynamic Capabilities Theory | Explain how firms sense, seize, and reconfigure resources with AI. |

| RBV | Resource-Based View | Mentioned as a contrasting theory that lacks dynamism in sustainability transitions. |

Appendix A

| Constructs | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI Capabilities → Entrepreneurial Orientation | 0.138 | 0.139 | 0.022 | 6.352 | 0.000 |

| AI Capabilities → Knowledge Management | 0.617 | 0.617 | 0.022 | 28.424 | 0.000 |

| AI Capabilities → Sustainable Entrepreneurship | 0.578 | 0.578 | 0.022 | 26.391 | 0.000 |

| Entrepreneurial Orientation → Sustainable Entrepreneurship | 0.039 | 0.040 | 0.025 | 1.548 | 0.122 |

| Entrepreneurial Orientation x Knowledge Management → Sustainable Entrepreneurship | 0.208 | 0.208 | 0.022 | 9.259 | 0.000 |

| Government Policy Support → Sustainable Entrepreneurship | −0.025 | −0.023 | 0.024 | 1.082 | 0.279 |

| Government Policy Support x Knowledge Management → Sustainable Entrepreneurship | 0.160 | 0.160 | 0.021 | 7.555 | 0.000 |

| Knowledge Management → Entrepreneurial Orientation | 0.223 | 0.225 | 0.032 | 6.947 | 0.000 |

| Knowledge Management → Sustainable Entrepreneurship | 0.408 | 0.409 | 0.030 | 13.541 | 0.000 |

| Constructs | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI Capabilities → Knowledge Management → Sustainable Entrepreneurship | 0.246 | 0.247 | 0.020 | 12.196 | 0.000 |

| Knowledge Management → Entrepreneurial Orientation → Sustainable Entrepreneurship | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 1.500 | 0.134 |

| AI Capabilities → Knowledge Management → Entrepreneurial Orientation → Sustainable Entrepreneurship | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 1.490 | 0.136 |

| AI Capabilities → Knowledge Management → Entrepreneurial Orientation | 0.138 | 0.139 | 0.022 | 6.352 | 0.000 |

References

- Kraus, S.; Kanbach, D.K.; Krysta, P.M.; Steinhoff, M.M.; Tomini, N. Facebook and the creation of the metaverse: Radical business model innovation or incremental transformation? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2022, 28, 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Proposing a definition and a framework of organisational sustainability: A review of efforts and a survey of approaches to change. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2030 Saudi Vision. Vison 2030 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 2016. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Annesi, N.; Battaglia, M.; Ceglia, I.; Mercuri, F. Navigating paradoxes: Building a sustainable strategy for an integrated ESG corporate governance. Manag. Decis. 2024, 63, 531–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, P. Improving learning and accountability in foreign aid. World Dev. 2020, 125, 104670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.U.; Zhang, J.; Saeed, I.; Ullah, S. Do institutional contingencies matter for green investment?—An institution based view of Chinese listed companies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, R.A.; Abdalkrim, G.M.; Shehawy, Y.M. Assessing the impact of business simulation as a teaching method for developing 21st century future skills. J. Int. Educ. Bus. 2023, 16, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.T.-T.; Demena, B.A. How does technology adoption affect energy intensity? Evidence from a meta-analysis. Appl. Energy 2025, 398, 126439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakash, M.; Bolisani, E. The transformative impact of AI on knowledge management processes. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2025, 31, 124–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujalli, A.; Wani, M.J.G.; Almgrashi, A.; Khormi, T.; Qahtani, M. Investigating the factors affecting the adoption of cloud accounting in Saudi Arabia’s small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, R.A.; Ahmed, I.; Faqihi, A.Y.A.; Shehawy, Y.M. Global Perspectives on Navigating Industry 5.0 Knowledge: Achieving Resilience, Sustainability, and Human-Centric Innovation in Manufacturing. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 16, 15997–16032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusa, R.; Suder, M.; Duda, J.; Czakon, W.; Juárez-Varón, D. Does knowledge management mediate the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance? J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 28, 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, M.J.G.; Loganathan, N.; Alamir, I.A.; Mujalli, A.; Almgrashi, A. Examining the emissions-growth nexus: Carbon impact, economic expansion, FDI, globalization, and trade in leading economies. J. Appl. Econ. 2025, 28, 2554712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Dou, J.; Qin, M.; Su, C.-W. Towards Sustainable Development: Assessing the Significance of World Uncertainty in Green Technology Innovation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, K.; Zhang, W.; Anwar, A.; Mustafa, S. Driving SME Sustainability via the Influence of Green Capital, HRM, and Leadership. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.M.; Suhluli, S. Generative AI and Cognitive Challenges in Research: Balancing Cognitive Load, Fatigue, and Human Resilience. Technologies 2025, 13, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamba, S.F.; Gunasekaran, A.; Akter, S.; Ren, S.J.F.; Dubey, R.; Childe, S.J. Big data analytics and firm performance: Effects of dynamic capabilities. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Palmer, C.; Kailer, N.; Kallinger, F.L.; Spitzer, J. Digital transformation: An overview of the current state of the art of research. Sage Open 2022, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masmali, F.H.; Khan, S.M.; Hakim, T. IoT-Enabled Digital Nudge Architecture for Sustainable Energy Behavior: An SEM-PLS Approach. Technologies 2025, 13, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalufi, N.A.M.; Sheikh, R.A.; Khan, S.M.F.A.; Onn, C.W. Evaluating the Impact of Sustainability Practices on Customer Relationship Quality: An SEM-PLS Approach to Align with SDG. Sustainability 2025, 17, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehawy, Y.M.; Khan, S.M.F.A. Consumer readiness for green consumption: The role of green awareness as a moderator of the relationship between green attitudes and purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, S.; Ferraris, A.; Rovelli, P.; Bertoldi, B. Digital transformation as a springboard for product innovation: The interplay between knowledge management and open innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 264–275. [Google Scholar]

- Borner, C.J.; Arndt, H.W. The double-edged sword of digitalization: Challenges and opportunities of artificial intelligence in sustainability. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 178, 121599. [Google Scholar]

- Crossan, M.M. Review of The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation, by I. Nonaka & H. Takeuchi. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 196–201. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/155381 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. Environmental sustainability in the service industry of transportation and logistics service providers: Systematic literature review and research directions. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2018, 53, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Kumar, A.; Upadhyay, A. How do green knowledge management and green technology innovation impact corporate environmental performance? Understanding the role of green knowledge acquisition. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 32, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.; Chiva, R. Linking entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The role of organizational learning capability and innovation. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroufkhani, P.; Wagner, R.; Ismail, W.K.W.; Baroto, M.B.; Nourani, M. Big data analytics and firm performance: A systematic review. Information 2019, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, D.; Parida, V.; Palmié, M.; Wincent, J. How AI capabilities enable business model innovation: Scaling AI through co-evolutionary processes and feedback loops. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H. The new field of sustainable entrepreneurship: Studying entrepreneurial action linking ‘what is to be sustained’ with ‘what is to be developed. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M.I. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentchev, N.A. and others. Integrating sustainable development in business: An analysis of 100 sustainability reports. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 593–614. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, P. Redefining stakeholder engagement: From control to collaboration. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 90, 539–551. [Google Scholar]

- Herzallah, F.; Mohammad, B.A.; Alhayek, M.; Khan, S.M.F.A. Mitigating uncertainty in travel agency selection in Jordan: A signaling theory approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2025, 5, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudice, M.D.; Scuotto, V.; Garcia-Perez, A.; Petruzzelli, A.M. A brief review of the literature on knowledge management and sustainability. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 1029–1047. [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Luiz, J.V.R.; Luiz, O.R.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Ndubisi, N.O.; de Oliveira, J.H.C.; Junior, F.H. Circular economy business models and operations management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 1525–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, M.J.G.; Alamir, I.A.; Ghazwani, M.; Ahmed, I.; Alkaraan, F.; Khan, M.A. Asymmetric Effect of Green Energy and Economic Growth on the Environmental Deterioration and the Environmental Kuznets Curve Validation in MENA Countries. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2024, 30, 3553–3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 770–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsudeen, K.; Liman, B.M.; Haruna, M.J. An empirical investigation on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention in Nigeria: A study of some selected students of higher learning. Saudi J. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2017, 2, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Covin, J.G.; Rigtering, J.P.C.; Hughes, M.; Kraus, S.; Cheng, C.F.; Bouncken, R.B. Individual and team entrepreneurial orientation: Scale development and configurations for success. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusa, R.; Duda, J.; Suder, M. Entrepreneurial orientation and knowledge management in SMEs: The role of institutional context. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 160, 113808. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, T.; Hoffmann, V.H. How hot is your bottom line? Linking carbon performance and financial performance. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 233–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, Z. Corrigendum to ‘Digitalization, trust, and sustainability transitions: Insights from two blockchain-based green experiments in China’s electricity sector’ [Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 50 (2024), 100801]. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2024, 50, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Halbusi, H.; Al-Sulaiti, K.I.; Alalwan, A.A.; Al-Busaidi, A.S. AI capability and green innovation impact on sustainable performance: Moderating role of big data and knowledge management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 210, 123897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Deng, Y. The impact of artificial intelligence on green economy efficiency under integrated governance. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, R.A.; Lanjewar, U.A. Decision Support System for Cotton Bales Blending Using Genetic Algorithm. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2010, 8, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, F.M.; Sorgner, A. New digital technologies and heterogeneous wage and employment dynamics in the United States: Evidence from individual-level data. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 175, 121381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, M.J.G.; Loganathan, N.; Mujalli, A. The impact of sustainable development goals (SDGs) on tourism growth. Empirical evidence from G-7 countries. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2397535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Carrion, G.; Cegarra-Navarro, J.G.; Cillo, V. Tips to use partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in knowledge management. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.T.; Lo, M.C.; Suaidi, M.K.; Mohamad, A.A.; Razak, Z.B. Knowledge Management Process, Entrepreneurial Orientation, and Performance in SMEs: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, S.; Edvardsson, I.R.; Foli, S. Knowledge management in SMEs: A follow-up literature review. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 25–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M.; Thi, T.D.P.; Nguyen, C.M.; Do, H.-D. Sustainable entrepreneurship and knowledge management: Role of green information technology in building sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems. J. Innov. Knowl. 2025, 10, 100689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandu, G.; Varganova, O.; Samii, B. Managing physical assets: A systematic review and a sustainable perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 61, 6652–6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodako, K.; Berbeka, J.; Rudnicki, M.; Łapczyński, M. The impact of innovation orientation and knowledge management on business services performance moderated by technological readiness. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 26, 674–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, D.; Shuhaiber, A.; Rawshdeh, Z. The impact of entrepreneurial orientation on innovation performance: The role of knowledge sharing as a mediating factor. J. Innov. Entrep. 2025, 14, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Taweel, G.M.; Al-Fifi, Z.; Abada, E.; Khemira, H.; Almalki, G.; Modafer, Y.; Khedher, K.M.; Yaseen, Z.M. Parrotfish: An overview of ecology, nutrition, and reproduction behaviour. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2023, 35, 102778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q.; Lai, K.H. An organizational theoretic review of green supply chain management literature. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 130, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, L.; Ardolino, M.; El Baz, J.; Gueli, G.; Bacchetti, A. The mediating role of knowledge management processes in the effective use of artificial intelligence in manufacturing firms. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2022, 42, 411–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E.; Gharbi, H.; Abdallah, M.A.B.; Hassan, O.H.M. Unveiling the role of knowledge management effectiveness in university’s performance through administrative departments’ innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2025, 11, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Alamer, A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: Guidelines using an applied example. Res. Methods Appl. Linguist. 2022, 1, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Guimarães, J.C.F.; Severo, E.A.; de Vasconcelos, C.R.M. The influence of entrepreneurial, market, knowledge management orientations on cleaner production and the sustainable competitive advantage. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1653–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Modernizing Small & Medium-Sized Enterprises in Saudi Arabia. 2023. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Modernizing_Small_Medium_Sized_Enterprises_in_Saudi_Arabia_2023.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Alharbi, G.L.; Aloud, M.E. The effects of knowledge management processes on service sector performance: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 566–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Springer Nature: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.M.; Shehawy, Y.M. Perceived AI Consumer-Driven Decision Integrity: Assessing Mediating Effect of Cognitive Load and Response Bias. Technologies 2025, 13, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Li, B.; Zhang, M. The impact of digital transformation on the efficiency of corporate resource allocation: Internal mechanisms and external environment. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 215, 124107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehawy, Y.M.; Khan, S.M.F.A.; Khalufi, N.A.M.; Abdullah, R.S. Customer adoption of robot: Synergizing customer acceptance of robot-assisted retail technologies. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Q.; Khan, S.M.A. Assessing Consumer Behavior in Sustainable Product Markets: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach with Partial Least Squares Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broccardo, L.; Truant, E.; Dana, L.-P. The interlink between digitalization, sustainability, and performance: An Italian context. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spender, J.C. Making knowledge the basis of a dynamic theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Du, M.; Bu, W.; Lin, T. Assessing the impact of economic growth target constraints on environmental pollution: Does environmental decentralization matter? J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 336, 117618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, R.; Joiner, K.; Abbasi, A. Improving students’ performance with time management skills. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kassar, A.N.; Singh, S.K. Green innovation and organizational performance: The influence of big data and the moderating role of management commitment and HR practices. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 144, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behravesh, S.-A.; Darnall, N.; Bretschneider, S. A framework for understanding sustainable public purchasing. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavy, B. Marco Iansiti and Karim Lakhani: Strategies for the new breed of ‘AI first’ organizations. Strategy Leadersh. 2020, 48, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, H. Artificial intelligence-enabled personalization in interactive marketing: A customer journey perspective. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin-Behravesh, S.-A.; Darnall, N.; No, W.; Bretschneider, S. How stakeholder influence shapes public sector environmental policy choices. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 523, 146312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 4; SmartPLS: Bönningstedt, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 25 January 2025).

| Construct | Theoretical Base | Major Debate/Contradiction | Gaps in the Literature | Link to Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | DCT, KBV | Efficiency paradox, energy cost, rebound/justice risk | Pathways from AI to SE still poorly understood | H1, H2, H7 |

| KM | KBV | Org. culture and absorptive capacity, underutilization | Green KM in emerging markets | H3, H4, H5, H6 |

| EO | DCT, KBV | Innovation or risk spiraling? | Moderating effect on KM → SE | H5 |

| GPS | Institutional Theory | Compliance vs. transformation, subsidy dependency | Boundary/spillover effects | H6, H8 |

| SE | All | TBL trade-off, authenticity | Measurement, contextual drivers | H4–H8 |

| Constructs | Cronbach’s α | rho_A | Composite Reliability (ρc) | AVE | AI | EO | GPS | KM | SE | EO × KM | GPS × KM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI Capabilities (AI) | 0.905 | 0.907 | 0.930 | 0.726 | – | 0.348 | 0.267 | 0.684 | 0.659 | 0.088 | 0.020 |

| Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO) | 0.910 | 0.914 | 0.933 | 0.736 | 0.348 | – | 0.047 | 0.245 | 0.255 | 0.008 | 0.034 |

| Government Policy Support (GPS) | 0.910 | 0.935 | 0.932 | 0.734 | 0.267 | 0.047 | – | 0.141 | 0.129 | 0.029 | 0.062 |

| Knowledge Management (KM) | 0.894 | 0.895 | 0.922 | 0.702 | 0.684 | 0.245 | 0.141 | – | 0.692 | 0.060 | 0.042 |

| Sustainable Entrepreneurship (SE) | 0.909 | 0.909 | 0.932 | 0.733 | 0.659 | 0.255 | 0.129 | 0.692 | – | 0.282 | 0.210 |

| EO × KM | – | – | – | – | 0.088 | 0.008 | 0.029 | 0.060 | 0.282 | – | 0.081 |

| GPS × KM | – | – | – | – | 0.020 | 0.034 | 0.062 | 0.042 | 0.210 | 0.081 | – |

| Category | Indicator | Value(s) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post hoc Power Analysis | Required Effect Size (α = 1%, 80% Power) | 0.107 | Minimum detectable effect; indicates sufficient sensitivity for small effects |

| Required Effect Size (α = 5%, 80% Power) | 0.084 | Demonstrates strong statistical power under standard significance level | |

| Required Effect Size (α = 1%, 90% Power) | 0.121 | Indicates ability to detect medium effects with high confidence | |

| Required Effect Size (α = 5%, 90% Power) | 0.098 | Confirms robust statistical adequacy for hypothesis testing | |

| Model Fit Indices | SRMR | Saturated = 0.033; Estimated = 0.050 | Values < 0.08 demonstrate good model fit |

| d_ULS | 0.356 (Sat.); 0.824 (Est.) | Lower values indicate better approximation of empirical data | |

| d_G | 0.158 (Sat.); 0.165 (Est.) | Acceptable consistency between empirical and model-implied matrices | |

| Chi-square | 820.692 (Sat.); 844.915 (Est.) | Indicates acceptable model–data discrepancy | |

| NFI | 0.944 (Sat.); 0.943 (Est.) | Values > 0.90 indicate strong model fit | |

| Explained Variance (R2) | Entrepreneurial Orientation | 0.050 (Adj. 0.049) | Weak explanatory power—suggests influence from additional external factors |

| Knowledge Management | 0.380 (Adj. 0.380) | Moderate explanatory power—indicates meaningful variance explained | |

| Sustainable Entrepreneurship | 0.540 (Adj. 0.536) | Substantial explanatory power—confirms strong predictive relevance | |

| Multicollinearity (VIF) | AI Indicators | 2.228–2.484 | All < 5, indicating no multicollinearity concerns |

| EO Indicators | 2.352–2.661 | Acceptable range, supporting construct independence | |

| GP Indicators | 2.340–2.768 | Below threshold; confirms model stability | |

| KM Indicators | 2.049–2.323 | Reflects acceptable variance inflation | |

| SE Indicators | 2.385–2.559 | Within recommended limits | |

| Interaction Terms | EO × KM = 1.000; GPS × KM = 1.000 | Perfect centering eliminates collinearity risk | |

| Predictive Relevance (Q2 predict) | Entrepreneurial Orientation | Q2 = 0.067; RMSE = 0.968; MAE = 0.807 | Indicates weak predictive accuracy, suggesting exploratory nature |

| Knowledge Management | Q2 = 0.378; RMSE = 0.790; MAE = 0.636 | Demonstrates strong predictive relevance | |

| Sustainable Entrepreneurship | Q2 = 0.368; RMSE = 0.797; MAE = 0.649 | Indicates strong predictive relevance for sustainability outcomes |

| Hypothesis | Path Relationship | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | t-Statistics | p-Value | Effect Size (f2) | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | AI Capabilities → Knowledge Management | 0.617 | 0.617 | 0.022 | 28.424 | 0.000 | 0.614 (Large) | Supported |

| H2 | AI Capabilities → Sustainable Entrepreneurship | 0.327 | 0.326 | 0.030 | 10.727 | 0.000 | 0.129 (Medium) | Supported |

| H3 | Knowledge Management → Entrepreneurial Orientation | 0.223 | 0.225 | 0.032 | 6.947 | 0.000 | 0.053 (Small–Medium) | Supported |

| H4 | Knowledge Management → Sustainable Entrepreneurship | 0.399 | 0.400 | 0.030 | 13.485 | 0.000 | 0.214 (Medium–Large) | Supported |

| H5 (Moderation) | Entrepreneurial Orientation × Knowledge Management → Sustainable Entrepreneurship | 0.208 | 0.208 | 0.022 | 9.259 | 0.000 | 0.092 (Small–Medium) | Supported |

| H6 (Moderation) | Government Policy Support × Knowledge Management → Sustainable Entrepreneurship | 0.160 | 0.160 | 0.021 | 7.555 | 0.000 | 0.056 (Small–Medium) | Supported |

| H7 | Entrepreneurial Orientation → Sustainable Entrepreneurship | 0.039 | 0.040 | 0.025 | 1.548 | 0.122 | 0.003 (Negligible) | Not Supported |

| H8 | Government Policy Support → Sustainable Entrepreneurship | 0.285 | 0.282 | 0.027 | 10.556 | 0.000 | 0.210 (Medium–Large) | Supported |

| Construct | Item Code | Questionnaire Statement | Importance (IPMA) | Performance (Revised) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI Capabilities (AI) | AI1 | AI supports decision-making in sustainability projects. | 0.139 | 68 |

| AI2 | AI identifies new sustainability opportunities. | 0.135 | 70 | |

| AI3 | AI optimizes resource use and environmental impact. | 0.141 | 65 | |

| AI4 | AI improves operational sustainability efficiency. | 0.125 | 67 | |

| AI5 | AI is integrated into long-term sustainability strategies. | 0.138 | 66 | |

| Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO) | EO1 | We seek innovative sustainability solutions. | 0.008 | 60 |

| EO2 | We exploit sustainability-driven opportunities. | 0.009 | 62 | |

| EO3 | We take calculated risks in sustainability ventures. | 0.009 | 59 | |

| EO4 | We lead in sustainability-oriented offerings. | 0.010 | 61 | |

| EO5 | Sustainability innovation is part of our strategy. | 0.010 | 63 | |

| Government Policy Support (GP) | GP1 | Regulations encourage sustainability entrepreneurship. | 0.007 | 57 |

| GP2 | Policy incentives support our initiatives. | 0.004 | 55 | |

| GP3 | National programs (Vision 2030, SDGs) influence practices. | 0.007 | 58 | |

| GP4 | Policies make sustainability implementation easier. | 0.006 | 56 | |

| GP5 | We receive adequate institutional support. | 0.005 | 54 | |

| Knowledge Management (KM) | KM1 | We acquire sustainability-related knowledge. | 0.101 | 64 |

| KM2 | Knowledge sharing supports sustainability. | 0.095 | 63 | |

| KM3 | We maintain sustainability knowledge repositories. | 0.092 | 61 | |

| KM4 | Knowledge application informs sustainability decisions. | 0.098 | 65 | |

| KM5 | We update our sustainability knowledge continuously. | 0.102 | 66 |

| Key Contribution | Summary of Findings/Novelty | Directions for Future Research |

|---|---|---|

| Integration of Digital, Organizational, and Institutional Factors | Demonstrates that AI capabilities, when combined with knowledge management (KM), entrepreneurial orientation (EO), and government policy support (GPS), most effectively advance sustainable entrepreneurship (SE) in emerging market SMEs. | Explore multi-level or cross-sector models in other emerging economies; test for differences in combinations of internal/external drivers. |

| Mediation Role of Knowledge Management | Establishes KM as a critical mediator that converts digital (AI) potential into actionable sustainability practices. | Conduct qualitative studies on KM processes and barriers in SMEs; investigate specific KM practices most linked to sustainability. |

| Moderating Impact of EO and GPS | Reveals that both EO and GPS magnify the KM → SE link, highlighting cultural and institutional contexts as amplifiers. | Longitudinal studies on how EO and GPS evolve; examine EO/GPS in various institutional settings or policy regimes. |

| Direct Effect of Government Policy Support (H8) | Confirms that government policy directly fosters SE, not merely as a moderator, validating the Institutional Theory’s claims in emerging contexts. | Assess long-term effects of policy dependency; compare effectiveness of different policy instruments or approaches. |

| Qualitative Managerial Insights | Shows from open-text responses that genuine SE outcomes require both internal champions and enabling environments—policy alone can foster compliance without transformation. | Case studies to understand “what works” on the ground; behavioral research on attitudes toward compliance versus innovation. |

| Saudi Context and Vision 2030 Blueprint | Offers empirical evidence for Vision 2030’s effectiveness in catalyzing SME sustainable transformation, with lessons for similar emerging markets. | Comparative policy analyses; adapt the model for various national development agendas and stages of digital maturity. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alshammakhi, Q.M.; Sheikh, R.A. Driving Sustainable Entrepreneurship Through AI and Knowledge Management: Evidence from SMEs in Emerging Economies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10928. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410928

Alshammakhi QM, Sheikh RA. Driving Sustainable Entrepreneurship Through AI and Knowledge Management: Evidence from SMEs in Emerging Economies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10928. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410928

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlshammakhi, Qasem Mohammed, and Riyaz Abdullah Sheikh. 2025. "Driving Sustainable Entrepreneurship Through AI and Knowledge Management: Evidence from SMEs in Emerging Economies" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10928. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410928

APA StyleAlshammakhi, Q. M., & Sheikh, R. A. (2025). Driving Sustainable Entrepreneurship Through AI and Knowledge Management: Evidence from SMEs in Emerging Economies. Sustainability, 17(24), 10928. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410928