Research Progress in Sustainable Mechanized Processing Technologies for Waste Agricultural Plastic Film in China

Abstract

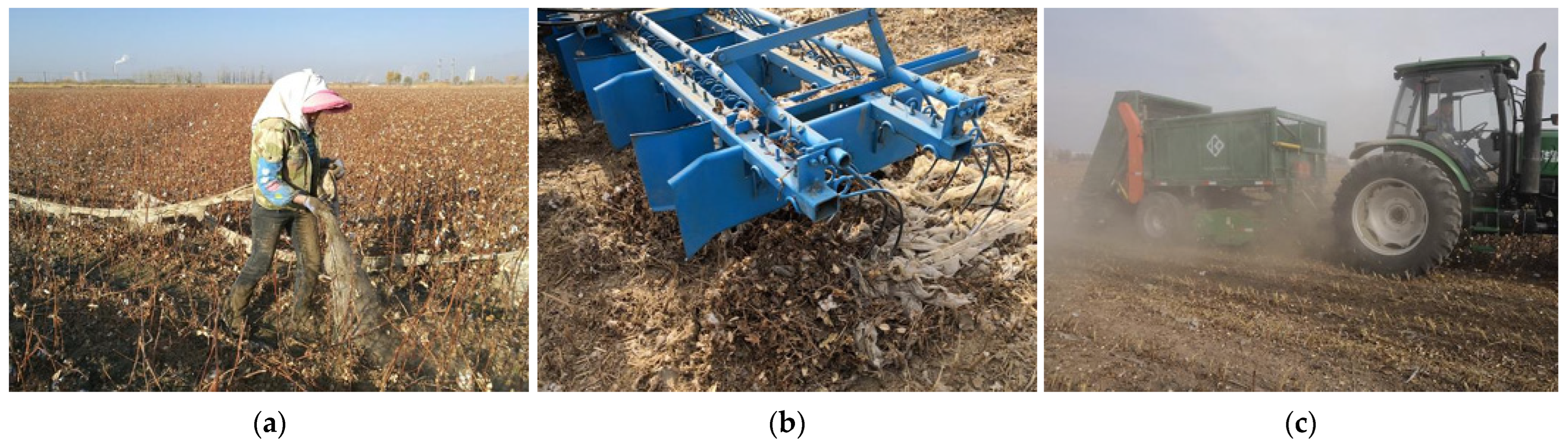

1. Introduction

2. Key Technologies for the Resourceful Utilization of Waste Agricultural Plastic Sheeting

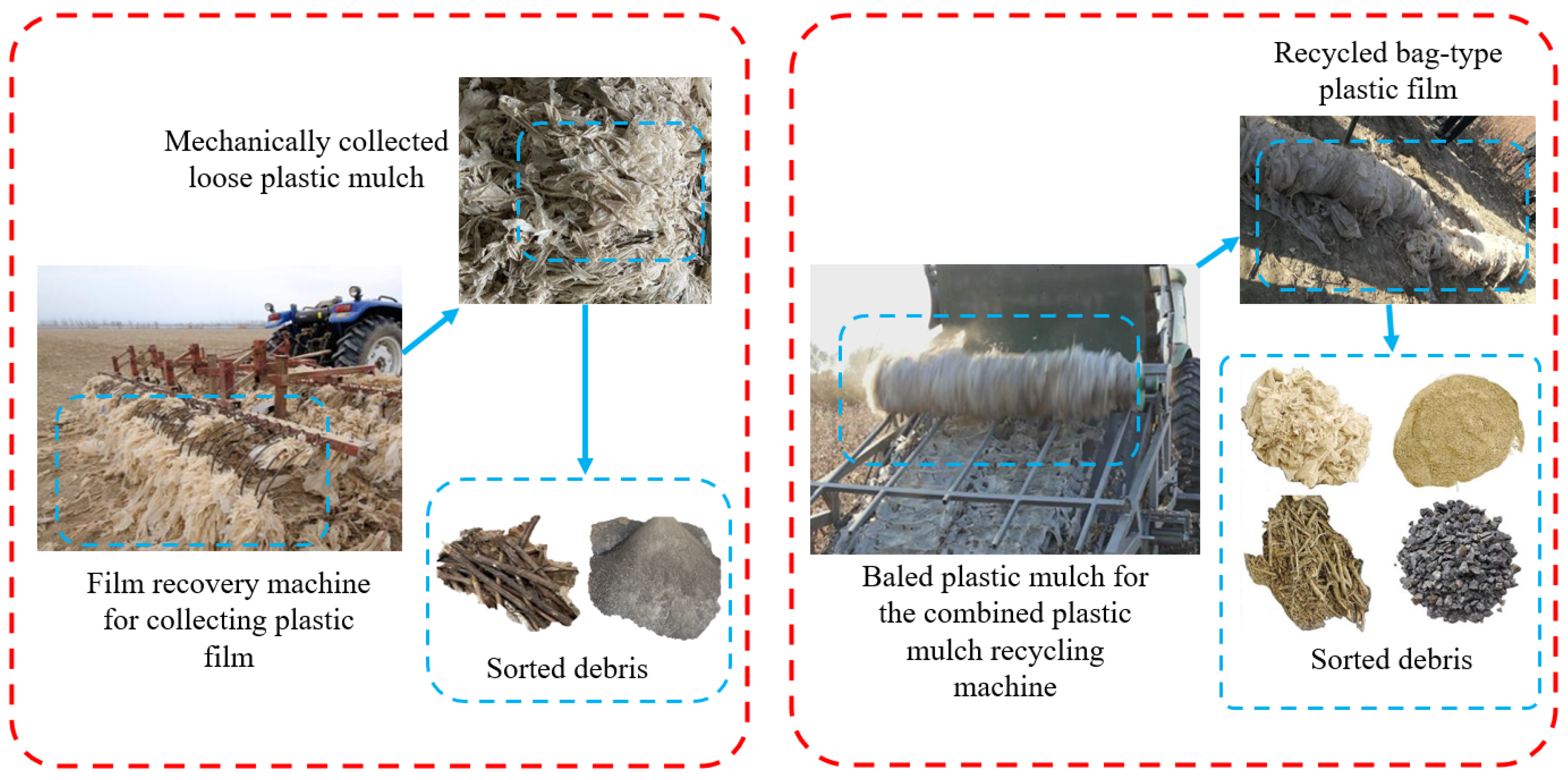

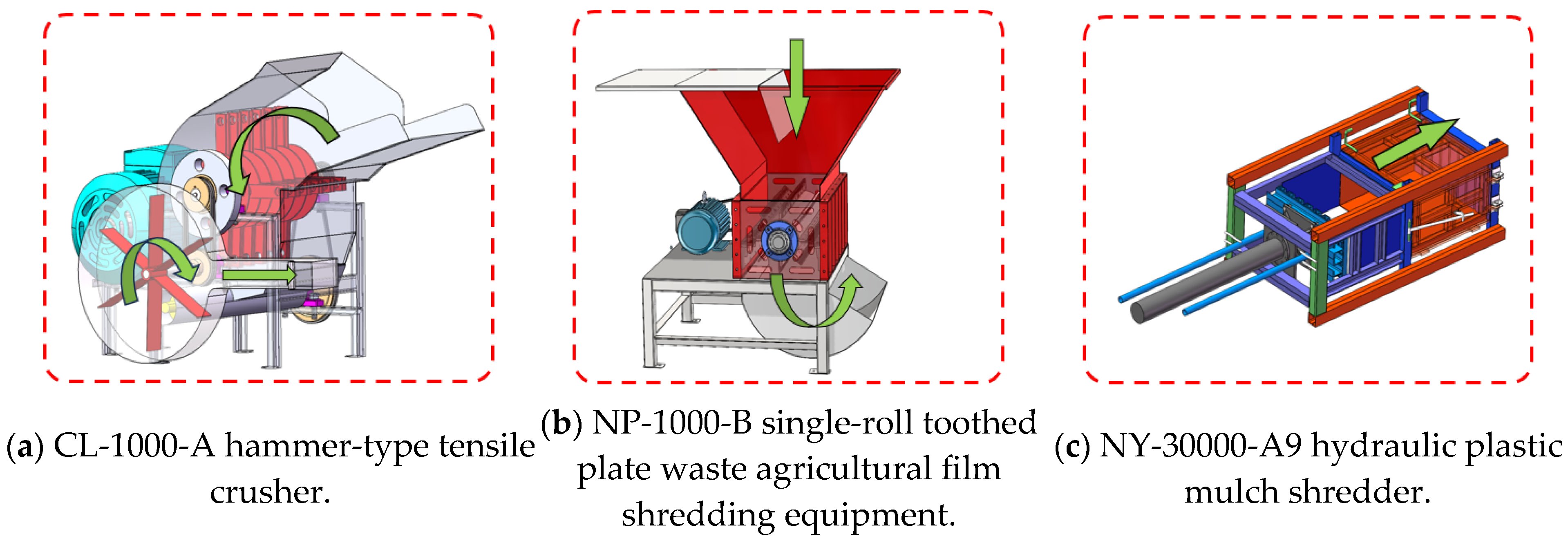

2.1. Plastic Mulch Shredding Technology

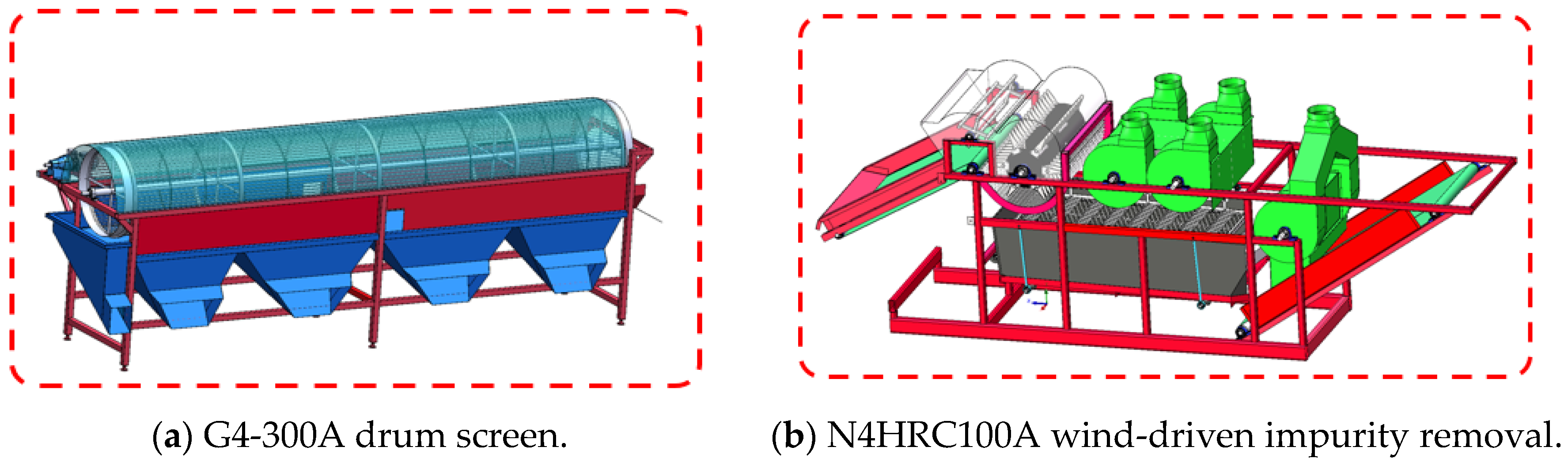

2.2. Film–Impurity Separation Technology

3. Current Status of Development in Waste Agricultural Film Shredding and Separation Technology

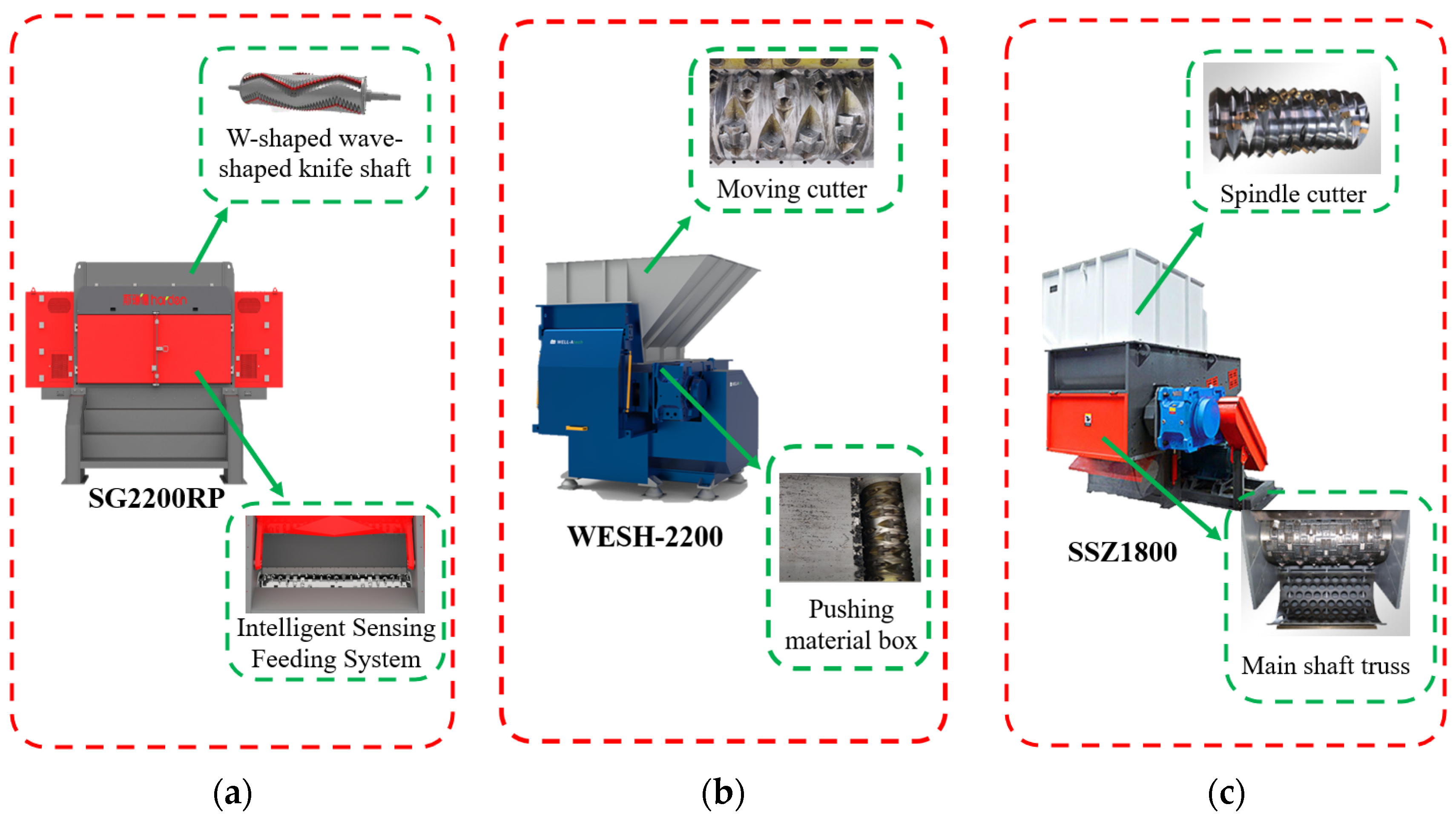

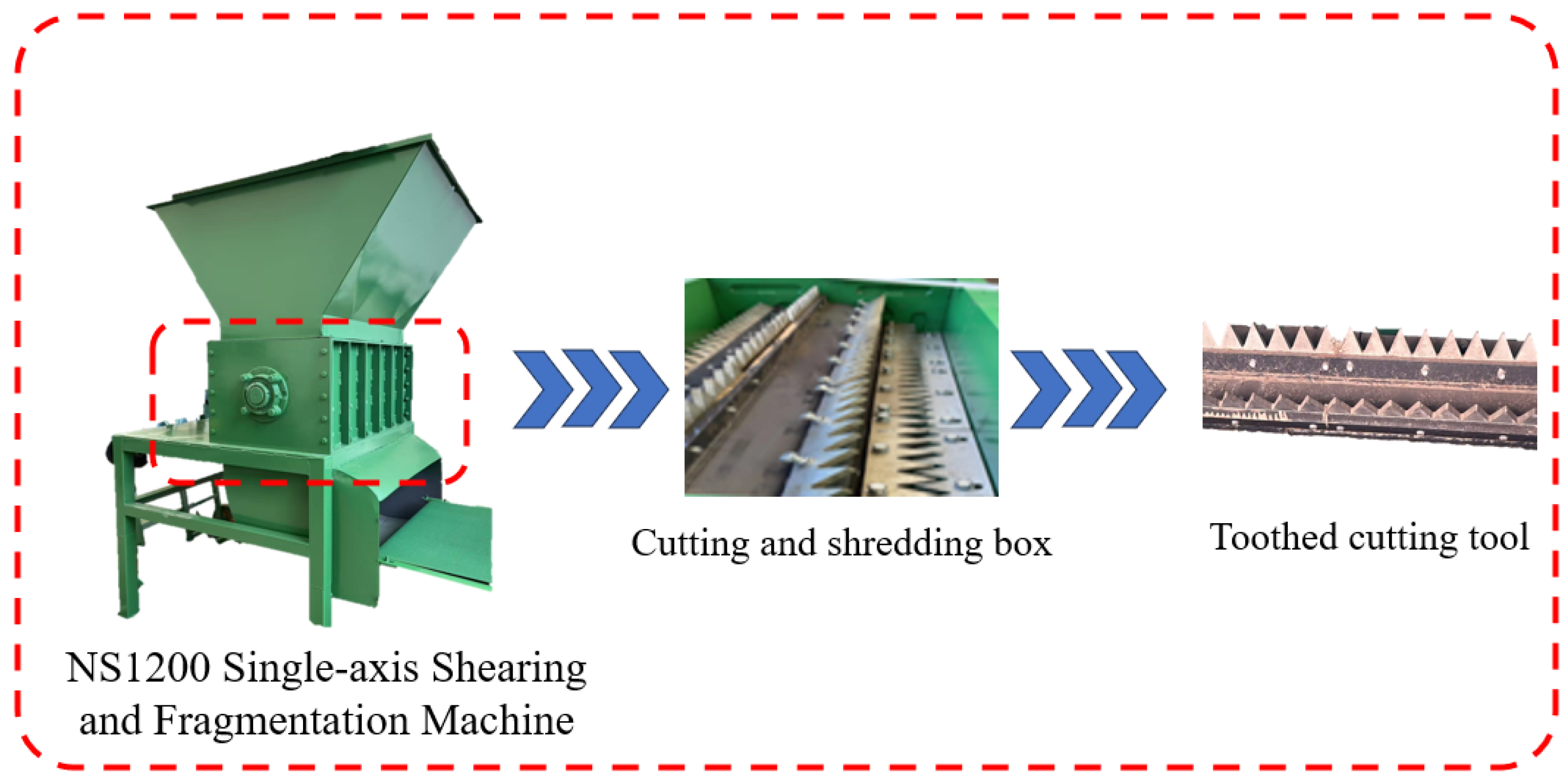

3.1. Current Status of Shredding Technology Development

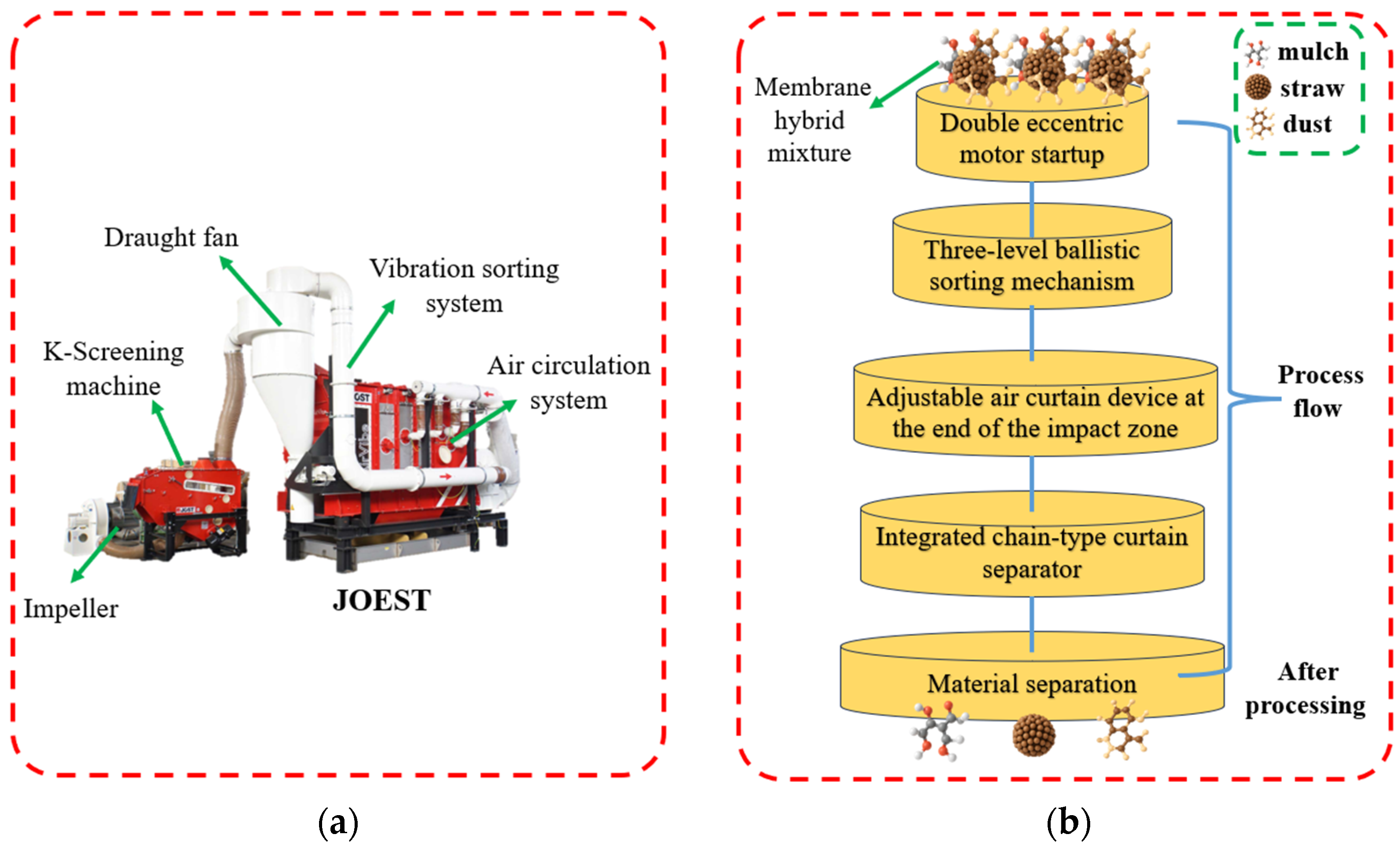

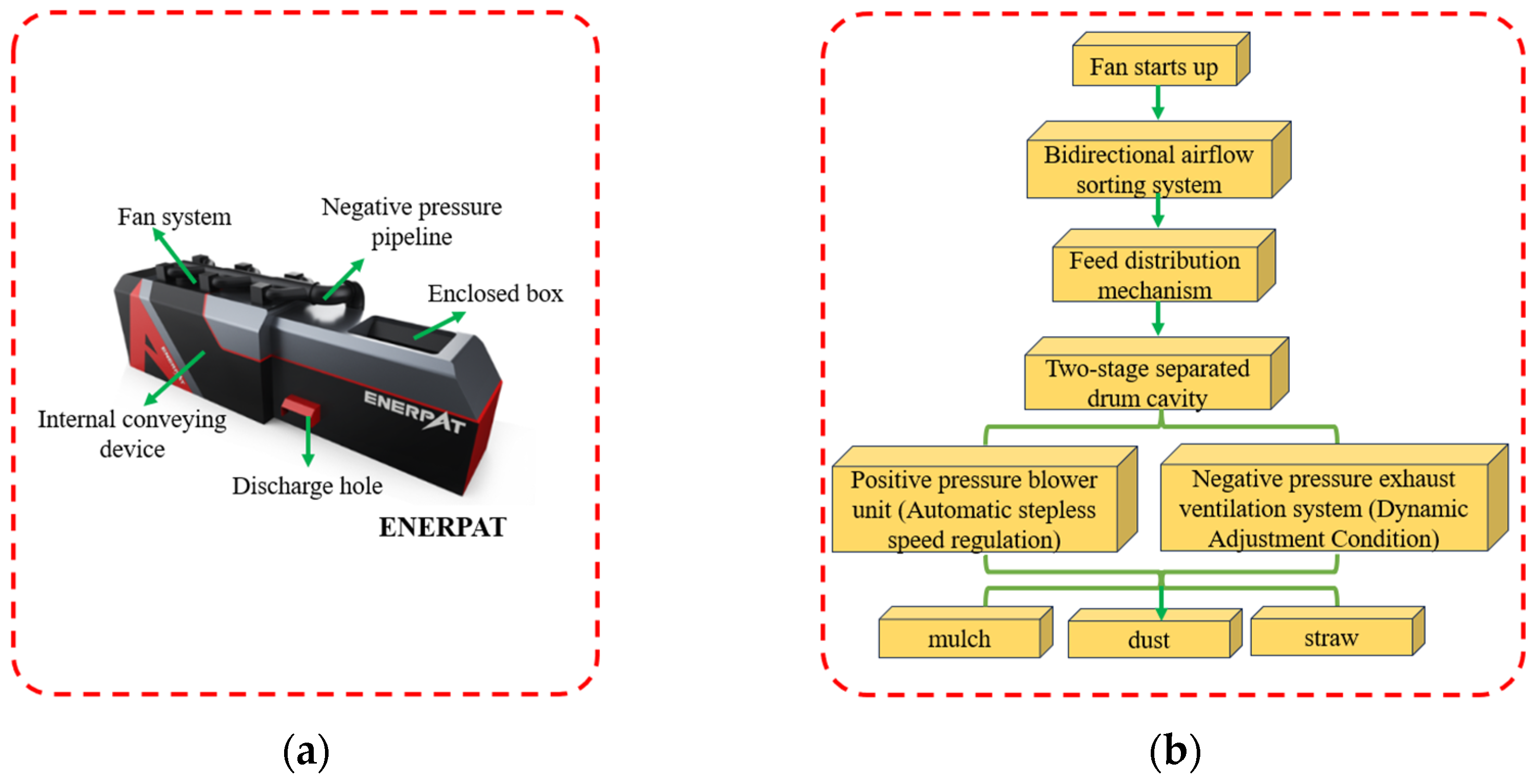

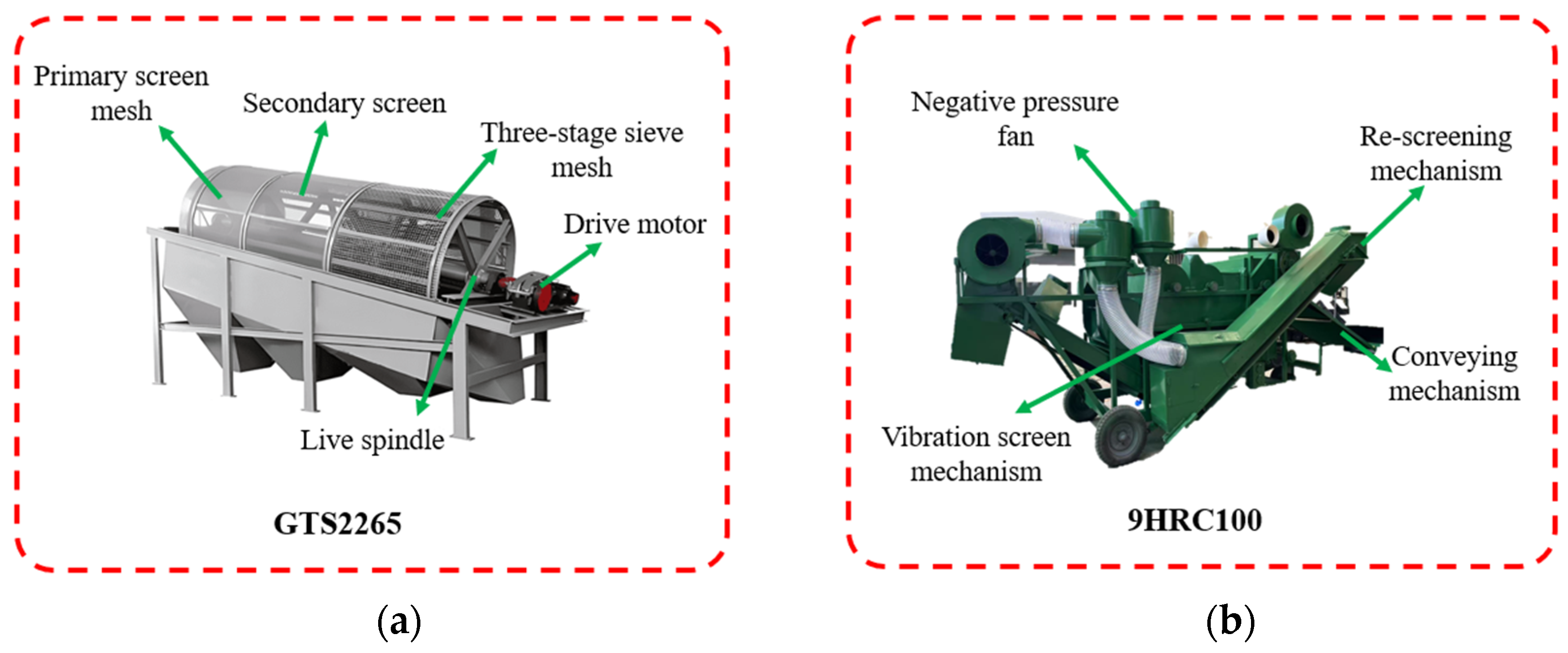

3.2. Separation Technology

4. Key Components for the Treatment of Waste Agricultural Plastic Film Pollution

4.1. Shredding Key Component Tools

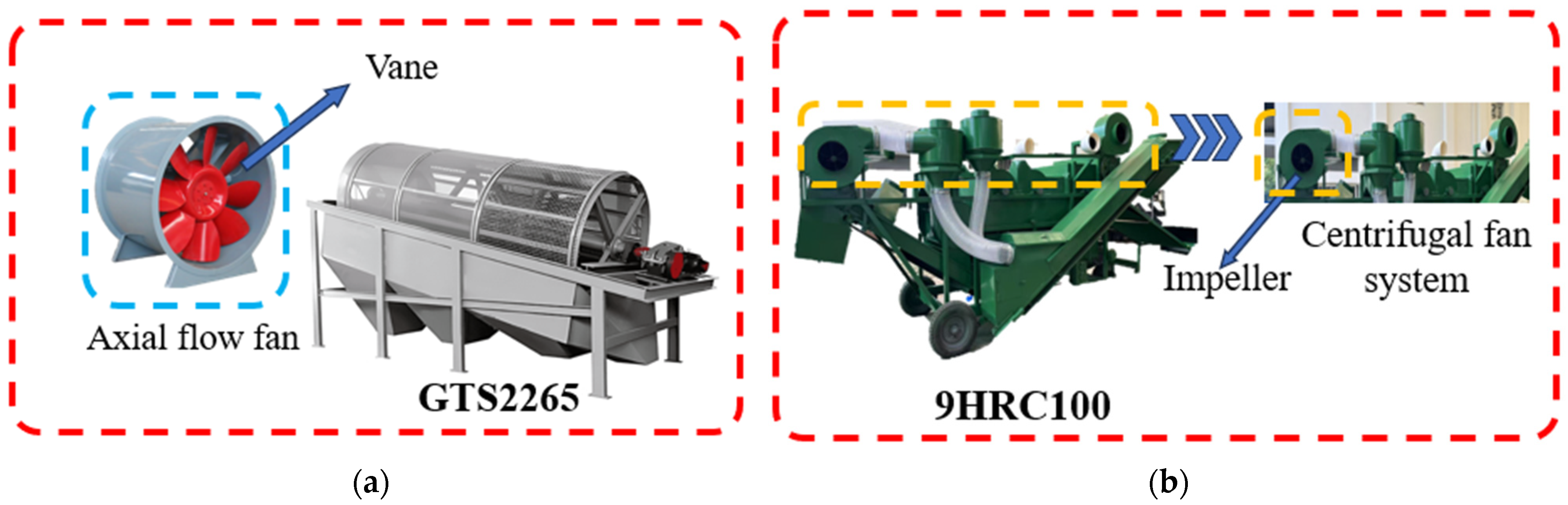

4.2. Separate the Key Component Fan

5. Issues and Discussions

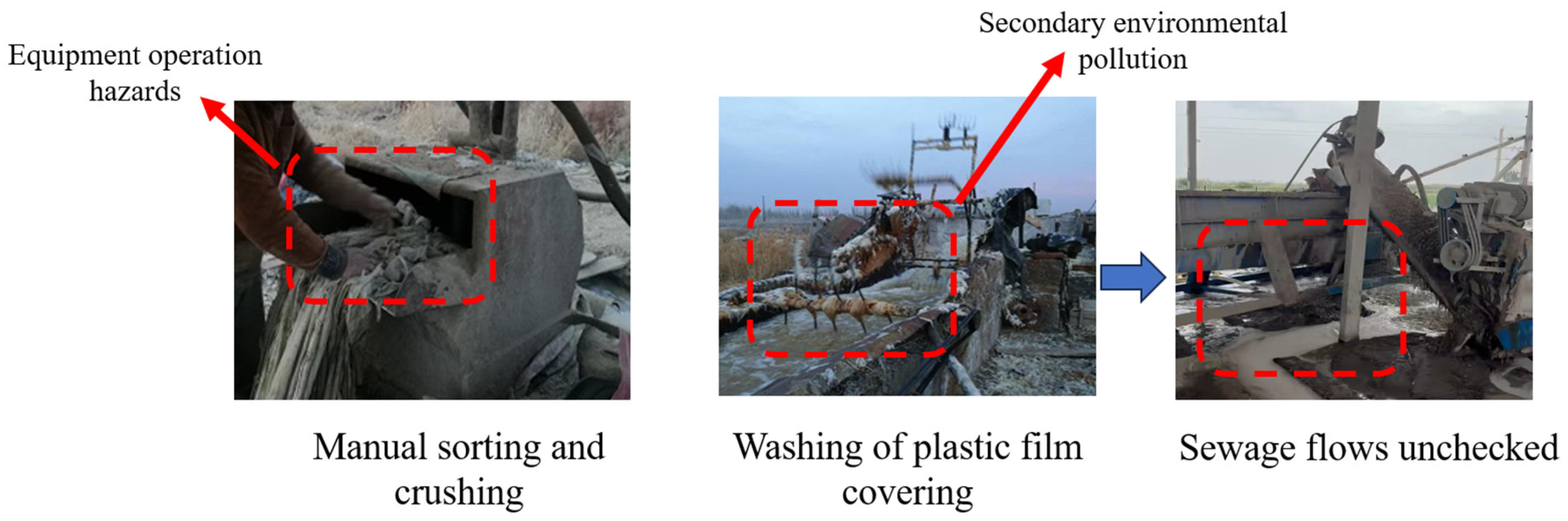

5.1. Existing Problems

5.1.1. Issues with Shredding Technology

5.1.2. Issues with Membrane Separation Technology

5.2. Recommendations

5.2.1. Recommendations for Shredding Technology Improvements

5.2.2. Recommendations for Improving Membrane Separation Technology

5.3. Discussion

6. Outlook

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Wen, H.; Zheng, X.; Niu, Q.; Kang, J. Research status and prospects of technologies for controlling farmland residual plastic-film pollution. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2017, 48, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Yang, X.; Liu, R.; Wu, T.; Huang, B. Research on residual plastic film in farmland and its prevention technologies. Green Sci. Technol. 2020, 24, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Lv, J.; Liu, Q.; Guo, Y.; He, W.; Wang, L.; Yan, C. Changes in major cotton-producing areas in China and residual plastic film pollution. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2021, 40, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, Y. Development of a precision seeder with double-film mulching for cotton. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2010, 26, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Shan, N.; Yang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y. Analysis of influencing factors of farmland residual plastic film in Xinjiang. J. Environ. Eng. Technol. 2024, 14, 1627–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, F. Research on the Utilization and Recycling of Agricultural Plastic Film and Related Fiscal Support Policies. Master’s Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, W.; Jin, Y.; Yao, J. Effects of residual plastic film on agricultural environment and countermeasures. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2024, 63, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. Reduction and efficiency improvement effects of high-strength plastic film in controlling agricultural non-point source pollution. Agric. Technol. 2023, 43, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Wang, Y. Review on residual plastic film pollution and prevention in Chinese farmland. China Cotton 2012, 39, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, W.; Liu, X.; Dai, F.; Shi, R.; Zhang, K.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Liang, J. Design and testing of a combined operation machine for corn straw crushing and residual film recycling. Agriculture 2025, 15, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Tang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, C. Current situation and control strategies of farmland residual film pollution in Xinjiang. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, Z.; Wu, F.; Guo, K.; Gu, F.; Cao, M. The use and recycling of agricultural plastic mulch in China: A review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S. Research on the Mechanism and Key Technologies of Cotton Stalk Returning and Residual Film Recovery Combined Operation Impurity Removal. Ph.D. Thesis, Xinjiang Agricultural University, Ürümqi, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X. Suggestions on mechanized recycling and comprehensive utilization of farmland residual film. China Agric. Mach. Equip. 2024, 6, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, H.; Chen, X.; Chen, H.; Gou, H. Current status and development of farmland residual film recovery machinery application. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2024, 43, 1271–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasenjiang, B.; Zhang, J.; Guo, G.; Airepati, M. Review and development trend of mechanized cotton stalk harvesting technology in Xinjiang cotton areas. J. Agric. Mechaniz. Res. 2025, 47, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Meng, H.; Jiang, P.; Peng, X.; Kan, Z.; Li, W. Residual film recovery methods and resource utilization in Xinjiang cotton fields: Current problems and countermeasures. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, L.; Yang, H.; Xu, H.; Shen, H.; Gu, M.; Luo, W.; Wu, F.; Gu, F.; Ren, G.; Hu, Z. Mechanized recycling of residual film from typical ridge and mulching crops in China: Current status, problems, and recommendations for sustainable agricultural development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Yan, L.; Chen, X.; Mo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, T. Design and experiment of longitudinal nail-tooth chain-type plastic film picking device. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2025, 56, 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Gou, H.; Wen, H.; Chen, X. Design and experiment of a secondary nail-tooth chain-plate type residual film recovery device. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2024, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Yierbolati, T.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, L. Current situation and development trend of mechanized recycling and resource utilization of waste plastic film in Xinjiang cotton fields. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 2024, 61, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Current situation of residual plastic film pollution in rural China and countermeasures. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Xianyang, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Xu, J.; Bai, R.; Liu, Q.; He, W.; Yan, C. Survey on farmers’ application and recycling behaviors of plastic film in typical regions of China. J. Agric. Resour. Environ. 2024, 41, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Meng, Q. Design and experiment of a stalk-pressing cotton field residual film recovery machine. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2023, 39, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpong, K.A.; Adesina, F.A.; DeVetter, L.W.; Zhang, K.; DeWhitt, K.; Englund, K.R.; Miles, C. Recycling agricultural plastic mulch: Limitations and opportunities in the United States. Circ. Agric. Syst. 2024, 4, e005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horodytska, O.; Valdés, F.J.; Fullana, A. Plastic flexible films waste management—A state of art review. Waste Manag. 2018, 77, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulati, A.; Zhan, L.; Xu, Z.; Yang, K. Obtaining the Value of Waste Polyethylene Mulch Film through Pretreatment and Recycling Technology in China. Waste Manag. 2025, 197, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Yang, H.; Cao, M.; Shen, H.; Chen, X.; Gu, F.; Wu, F.; Hu, Z. Design and optimization of a toothed-plate single-roller crushing device for waste plastic film. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Hu, B.; Luo, X.; He, H.; Guo, M.; Wang, C. Experimental study on shear characteristics of film-stalk mixture. J. Agric. Mechaniz. Res. 2023, 45, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Hong, J.; Cao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J. Design and experiment of a cotton stalk crushing and film-following strip-gathering machine. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2022, 38, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ma, Y.; Ji, R. Aging Processes of Polyethylene Mulch Films and Preparation of Microplastics with Environmental Characteristics. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 107, 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-C.; Weir, M.P.; Truss, R.W.; Garvey, C.J.; Nicholson, T.M.; Halley, P.J. A Fundamental Study on Photo-Oxidative Degradation of Linear Low Density Polyethylene Films at Embrittlement. Polymer 2012, 53, 2385–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, B.; Ru, S.; Chen, X.; Yan, L.; Wu, J. Review of agricultural plastic film recycling equipment from China. INMATEH Agric. Eng. 2024, 74, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Hou, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, T. Contact analysis and experiment of elastic tooth film-picking based on mechanical properties of residual film. J. Agric. Mechaniz. Res. 2016, 38, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Design and Experiment of a Stalk-Pressing Cotton Field Residual Film Recovery Machine Based on Soil–Film Adhesion Analysis. Master’s Thesis, Xinjiang Agricultural University, Ürümqi, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Kanzha; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Yang, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, B.; Yan, W.; Feng, Z.; Li, Y. Design and experiment of a multi-stage crusher for film–impurity bundles. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2024, 40, 187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Feng, Z.; Li, J.; Kanzha; Bai, Q.; Meng, H. Design and experiment of a single-roller square-blade crushing device for machine-harvested cotton film–impurity round bales. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2025, 41, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. Research on Peanut Film–Seedling Separation Technology with Wind–Sieve Combination and Mechanism Optimization. Master’s Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Han, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhu, B. Research progress on waste plastic film separation technology. Contemp. Petrochem. 2024, 32, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J. Discussion on dry-cleaning technology for recycling waste agricultural plastic film. Rubber Plast. Resour. Util. 2024, 55, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, X.; Wen, H. Recycling and reprocessing technologies of agricultural residual film. Xinjiang Agric. Mechaniz. 2021, 28–30, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, X.; Wen, H. Research and experiment on the removal mechanism of light impurities of the residual mulch film recovery machine. Agriculture 2022, 12, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Huang, Y. Research status of separation machinery for residual film–impurity mixtures after mechanical harvesting. Mod. Agric. Mach. 2022, 4, 119–121. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Niu, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Yang, H. Design of a drum screen wind-sorting device for waste plastic film and impurities. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2017, 33, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z. Study on density separation method for polyethylene (PE) in waste plastics. Sichuan Chem. Ind. 2023, 26, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, C.; Tian, B.; Nie, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, W. Research progress on waste plastic sorting technology. Chem. Miner. Process. 2024, 53, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Xie, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; Peng, Q. Design and experiment of a sieve-hole unclogging device for a drum-type film–impurity wind separator. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P.; Chen, X.; Meng, H.; Liang, R.; Zhang, B.; Kanzha. Design and experiment of a drum-type soil-removal device for machine-harvested film–impurity mixtures. J. Jilin Univ. (Eng. Technol. Ed.) 2023, 53, 2718–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zuo, B.; Huang, R. Research on recycling and industrialization progress of PET plastic resources. Guangdong Chem. Ind. 2024, 51, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Guo, H.; Wu, S.; Wu, M.; Zhu, X. Problems and countermeasures in mechanized recovery of residual film. Hebei Agric. Mach. 2024, 23, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Ji, C.; Chen, X.; Wu, J. Parameter optimization of farmland residual film compression molding. J. China Agric. Univ. 2019, 24, 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Enerpat Single Shaft Shredder. Available online: https://www.enerpat.com.cn/danzhouposuijixin.html (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Eldan Recycling Shredders. Available online: https://www.eldan-recycling.com/shredders/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Siruide Single Shaft Shredder. Available online: https://www.siruide.com/danzhouposuiji.html (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Welle Single Shaft Shredder. Available online: http://wellepa.com/ (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Single Shaft Shredder. Available online: http://www.ishredder.cn/Singleshaftshredder.html (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Liu, Z. Progress of the world plastics industry (2020–2021, Part I: General Plastics). Plast. Ind. 2022, 50, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, K. Progress of the world plastics industry (2021–2022, Part I: General Plastics). Plast. Ind. 2023, 51, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chokin, K.; Yedilbayev, B.; Chokin, T.; Medvedev, A. Air Classification of Crushed Materials. Evergreen 2023, 10, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinurov, V.; Kharkov, V.; Pankratov, E.; Dmitriev, A. Numerical Study of Vortex Flow in a Classifier with Coaxial Tubes. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Innov. 2022, 12, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JOEST China. Available online: https://www.joestchina.com/ (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Enerpat. Air Separator, Airflow Separator, Horizontal Air Separator. Available online: https://www.enerpat.com.cn/pd42073372.html (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Shanghai Dingbo. GS Trommel Screen. Available online: https://www.shdbzg.com/1388.html/ (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Politiek, R.G.A.; He, S.; Wilms, P.F.C.; Keppler, J.K.; Bruins, M.E.; Schutyser, M.A.I. Effect of Relative Humidity on Milling and Air Classification Explained by Particle Dispersion and Flowability. J. Food Eng. 2023, 358, 111663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Z.; Isaac, B.; Tumuluru, J.S.; Yancey, N. Grinding and Pelleting Characteristics of Municipal Solid Waste Fractions. Energies 2024, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Kan, Z.; Li, J.; He, Q.; Wen, B.; Li, J. Effects of different elements on the wear performance of horizontal TMR mixer blades. Chin. J. Agric. Mech. 2019, 40, 89–93, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Li, J.; Wen, B.; Kan, Z. Analysis of rubbing–cutting mechanism and parameter optimization of an auger-type straw chopping device. J. Agric. Mechaniz. Res. 2018, 40, 157–161, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, J.; Du, Y.; Huang, W.; Liu, Y.; Yue, Y. Design and experiment of a rotary-knife and axial-flow drum combined crushing–separating device for film–impurity mixtures. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2025, 56, 409–421, 456. [Google Scholar]

- Zerma. ZSS Single Shaft Shredder. Available online: https://zerma.com/chinese/machinery/shredder.html#id_zss (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Tian, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Yan, L.; Wen, H.; Gou, H. Design and experiment of key components for a cotton stalk crushing and film-raking combined operation machine. J. Gansu Agric. Univ. 2019, 54, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K. Analysis of tool wear and control in shear-type municipal solid waste shredders. Low Carbon World 2020, 10, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhang, Y. Three-dimensional modeling design and computer simulation machining of roller-cutting knife edge. J. Liaoning Univ. Petrol. Chem. Technol. 2005, 25, 58–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Guan, H.; Peng, X.; Mu, G. Optimization study on shear-type shredder cutter parameters. Constr. Mach. 2022, 9, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z. Cause analysis of cracking in the chopping drum cutter disk of a self-propelled silage harvester. Equip. Manag. Maint. 2023, 2, 150–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Zhu, S. Simulation analysis and design of cutting edge angle of chemical fiber cutting knives. Tool Eng. 2010, 44, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K. Key Technology Research on Pre-Treatment (Crushing) for Recycling Waste Plastic Film. Master’s Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, J.; Xue, D.; Han, J.; Hou, S. Development status of plastic film application and recycling equipment at home and abroad. J. Agric. Mechaniz. Res. 2013, 35, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Ji, J.; Chen, P.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, M. Design and experiment of a dual-air-duct cross-flow fan. J. Agric. Mechaniz. Res. 2025, 47, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, S. Design and experiment of a peanut harvester cleaning device based on EDEM simulation. J. Agric. Mechaniz. Res. 2025, 47, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Y. Research on Rapid Design Method of Combine Harvester Cleaning Device. Master’s Thesis, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, T.; Qiu, M.; Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Shi, Z. Numerical simulation and optimization of collector parameters of agricultural axial-flow fans. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 342–353. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Modal and dynamic response analysis of axial fan blades. Coal Mine Mach. 2024, 45, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T. Numerical Analysis of Low-Pressure Axial Fan Flow Field and Blade Structure Optimization. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, T. Experimental Study on Air-Suction Impurity-Removal Components of a Tiger Nut Harvester. Master’s Thesis, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Optimization of Aerodynamic Performance and Internal Flow Characteristics of High-Speed Centrifugal Fans for Vacuum Cleaners. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, Hangzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Man, C.; Zhou, H.; Luo, L.; Xue, M.; Jiang, A. Aerodynamic performance and noise optimization of centrifugal fan impellers. Fan Technol. 2022, 64, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Tian, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Chen, D. Design and experiment of a dual-cone centrifugal cleaning fan for half-feed combine harvesters. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Qian, H. Aerodynamic characteristics of variable-pitch axial ventilation fan blades under abnormal installation angle conditions. Proc. Chin. Soc. Electr. Eng. 2009, 29, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, X. Structure and installation of industrial centrifugal fans. World Nonferrous Met. 2024, 1, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.; Zhang, X.; Ouyang, Z.; Luo, H.; Fang, Y.; Wu, B. Experimental study on a centrifugal–axial combined cleaning fan. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2007, 23, 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Huang, X.; Xiang, Y. Effects of blade installation angle on internal flow field and performance of axial ventilation fans. Min. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2013, 40, 114–117. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Yang, X. Study on a method of use for centrifugal fan impellers. Shandong Chem. Ind. 2024, 53, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhou, C. Recycling, Disposal, or Biodegradable-Alternative of Polyethylene Plastic Film for Agricultural Mulching? A Life Cycle Analysis of Their Environmental Impacts. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 134950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Equipment Model | Motor Power(kw) | Heavy-Duty Throughput (t/h) | Production Efficiency (t/h/kw) | Energy Consumption per Unit (kwh/t) | Applicable Materials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSA-F1500 [52] | 75 | 5 | 0.067 | 15 | Conventional plastics, lightweight solid waste (PE, PP, thin-walled plastics, etc.) |

| MC1348 FD220 [53] | 300 | 6 | 0.020 | 50 | Municipal solid waste (MSW), plastics and plastic packaging, textiles, wind turbine blade segments, etc. |

| SG2200RP [54] | 320 | 6 | 0.019 | 53.3 | Mixed waste plastics, industrial solid waste, refuse-derived fuel (RDF), paper mill waste, biomass straw and other solid waste materials |

| WESH-2200 [55] | 264 | 5 | 0.019 | 52.8 | Volume reduction in bulky and industrial solid waste: textiles, leather, plastic film, industrial paper, RDF/SRF pre-treatment, aluminum cans/shavings |

| SSZ1800 [56] | 110 | 6 | 0.0545 | 18.33 | Plastic products, films, woven sacks, paper products, timber, light metal foils, domestic/industrial solid waste, etc. |

| Indicator | Single-Shaft Shear Crushing (with Screen) | Dual-Shaft Shredding (without Screen) | Separation Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| D10 (mm) [52,53,54,55,56] | 8–15 | 30–45 | Single-shaft design for finer processing, suitable for wind-sorting preliminary screening. |

| D50 (mm) [52,53,54,55,56] | 25–35 | 60–90 | Single-axis particle size is more stable and offers greater controllability. |

| D90 (mm) [52,53,54,55,56] | 40–50 | 120–180 | The twin-shaft cannot be directly employed for air separation/screening. |

| Particle size distribution width | Narrow | Broad | Single-axis operation facilitates more stable sorting. |

| Flake proportion | 70–85% | 40–55% | Flat pieces are more conducive to air separation. |

| Strip ratio | <3% | 10–25% | The dual-axis strip configuration causes entanglement and complicates sorting. |

| Subsequent sorting efficiency | High | Low | Single-axis is preferable to dual-axis. |

| Blade type | Block-shaped cutting tool + fixed tool, single-axis machining | Hook-shaped/claw-shaped double-axis interlocking blades | Blade shape determines particle form: Single-axis blades more readily form flakes, facilitating separation. |

| Power consumption | Generally employed for fine crushing, with relatively high power consumption per unit output | Primarily employed for coarse crushing, with relatively low power consumption per unit output (though individual units typically feature substantial motor power ratings) | Power consumption impacts operational costs and the overall energy efficiency of the sorting line. |

| Entanglement risk | Low, with material predominantly cut into short segments, resulting in a low likelihood of entanglement | Tall, prone to causing long, strip-like materials to become entangled around the cutter shaft and conveying equipment | Wrapping may result in downtime for cleaning, affecting continuous sorting and equipment reliability. |

| Equipment Model | Motor Power (kw) | Throughput (t/h) | Production Efficiency (t/h/kw) | Energy Consumption per Unit (kwh/t) | Applicable Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AirVibe [62] | 22 | 10–15 | 0.455–0.682 | 1.5–2.2 | Rough separation |

| GTS2265 [63] | 30 | 80 | 2.667 | 0.375 | Rough separation |

| 9HRC100 [35] | 22 | 1–1.5 | 0.046–0.068 | 14.7–22 | Precise separation |

| Comparison Dimension | Roller Cutter | Shear Cutter | Applicability Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core structure | Rotating drum body + helical surface/flat blade (30–45° cutting edge angle) [71] | Double-edged parallel blades + bolt-on U-groove (thickness 1.6–4.5mm) [72] | Roller type complex structure (need to throw components), shear type compact and easy to maintain |

| Cutting Mechanism | Sliding cut with movable and stationary knives (sliding cut angle 12–18°) [71] | Double-edge bite shear [72] | Roller slide cut to reduce hard impact, shear to avoid stretching of flexible materials |

| Cutting performance | |||

| Efficiency | 30–48 m/s high speed cutting (drum speed 1400–1800 r/min) [72] | Low-speed layered shear [73] | Roller type 40% more efficient (hard straw), shear type for continuous film processing |

| Power wastage | High power consumption (rotational kinetic energy required) | Low energy consumption (rated 120–540 W) | Hard materials choose roller type (e.g., corn stalks), film and other flexible materials choose shear type |

| Crushing quality | Uniformity of broken sections (load-balanced design) | Flat cuts (edge shot peening) | Roller type for green feed (good palatability of broken pieces), shear type for plastic recycling |

| Damage resistance | Wear-resistant with large cutting angles (30–45°) [74] | Stress concentration in the bolt (max. 1.5 × 107 Pa) [75] | Roller type lasts 3 times longer (hard conditions), shear type requires regular bolt replacement |

| Special design | Herringbone moving knife configuration (reduces sidewall friction) [70] | Compaction mechanism + sieve plate (anti-film entanglement) [76] | Priority is given to roller type (anti-clogging) for high humidity materials, and shear type is necessary for highly ductile films. |

| Typical application | Silage harvesting (JAGVAR 830 model) [72] | Waste mulch recycling (42° optimal edge angle) [74] | Hard straw: roller (>90% crushing) Flexible mulch: shear attachment loss |

| Performance Indicators | Axial Fans | Centrifugal Fans | Applicability Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wind pressure range | ≤15 kPa (low to medium pressure) [80] | Up to 6.7 kPa (7 kPa for high-pressure models) Low to medium flow rate (specific speed < 100) [85] | Centrifugal type with high air pressure is more suitable for straw conveying |

| Airflow characteristics | High flow rate (specific speed > 100) | Low to medium flow rate (specific speed < 100) | Axial flow type is suitable for large area film blowing and floating |

| Airflow direction | Axial flow (parallel flow) [86] | Radial flow (worm gear expansion) [87] | More uniform axial airflow reduces film entanglement |

| Sundry handling capacity | |||

| Mulch blown-out effect | Wide coverage of 7–10 m/s wind speeds [83] | Localized high-pressure airflow tends to tear film | Axial low-velocity winds reduce mulch breakage |

| Straw handling capacity | Insufficient wind pressure (weak fiber penetration) [88] | Effective throwing with high wind pressure (e.g., 6664 Pa model) [88] | Centrifugal straw blowing clean rate > 85 |

| Energy efficiency performance | High efficiency (average > 80%) | Lower efficiency (up to 85.5% for backward curved blade type) | Higher power density for axial flow |

| Structural properties | |||

| Volume/weight ratio | Small size/light weight (small mass-to-power ratio) | Bulky construction (high mass-to-power ratio) | Axial flow for easier integration of mobile devices |

| Anti-blocking design | Straight runners are less prone to clogging [89] | Fibrous debris tends to accumulate in the worm’s shell [90] | Preferred axial flow for mulch-straw mixtures |

| Adjustment performance | Good economy (adjustable moving/guiding vanes) [91] | Poor regulation economy [92] | Axial flow for real-time optimization of scavenging air velocity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pei, J.; Cao, M.; Yang, H.; Gu, F.; Wu, F.; Gu, M.; Chen, P.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, P. Research Progress in Sustainable Mechanized Processing Technologies for Waste Agricultural Plastic Film in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10926. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410926

Pei J, Cao M, Yang H, Gu F, Wu F, Gu M, Chen P, Zhao C, Zhang P. Research Progress in Sustainable Mechanized Processing Technologies for Waste Agricultural Plastic Film in China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10926. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410926

Chicago/Turabian StylePei, Jiayong, Mingzhu Cao, Hongguang Yang, Fengwei Gu, Feng Wu, Man Gu, Peng Chen, Chenxu Zhao, and Peng Zhang. 2025. "Research Progress in Sustainable Mechanized Processing Technologies for Waste Agricultural Plastic Film in China" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10926. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410926

APA StylePei, J., Cao, M., Yang, H., Gu, F., Wu, F., Gu, M., Chen, P., Zhao, C., & Zhang, P. (2025). Research Progress in Sustainable Mechanized Processing Technologies for Waste Agricultural Plastic Film in China. Sustainability, 17(24), 10926. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410926