1. Introduction

Renewable energy plays a crucial role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and diversifying the energy supply. Renewables accounted for 29% of global electricity generation in 2020. Driven by wind power and PV, more than 256 × 10

6 kW of capacity was added in 2020, marking nearly a 10% increase in total installed renewable power capacity [

1]. To sustain the rapid expansion of renewable electricity, continued incentive policies are essential to encourage further deployment of clean energy sources. Based on the experiences of countries advancing renewable electricity, key incentive policies include feed-in tariff subsidies and renewable energy portfolio standards. Understanding the relationship between these incentive policies and the development of renewable electricity is critical for shaping future energy strategies.

China is the fastest-growing country in terms of installed renewable electricity capacity globally [

1]. To achieve this rapid growth, the Chinese government has provided substantial subsidies to stimulate the development of these renewable energy industries. As noted [

2], total subsidies for wind and PV power generation exceeded 60 billion RMB in 2015 alone. Given the government’s considerable expenditure on these incentives, it is essential to evaluate the effectiveness of the FIT subsidy policy and its impact on the development of the PV and wind energy sectors.

The feed-in tariff (FIT) subsidy policy, which offers fixed tariffs for wind and PV energy significantly higher than the benchmark price for coal-fired electricity, aims to rectify cost distortions in renewable energy power generation (REPG) technologies. However, on the one hand, if the fixed subsidy is low compared to the cost distortion of new technologies, it will cause policy failure. On the other hand, if the fixed subsidy is much higher compared to the cost distortion, it will cause overinvestment and resource waste [

3].

We use county-level data on PV and wind power capacity and generation in China from 2005 to 2017, compiled from national power industry statistics, to analyze the impact of fixed FIT subsidies on these metrics. Our identification strategy leverages variations in subsidy levels and policy implementation timing across counties to evaluate the impact of these subsidies using a difference-in-differences (DID) model. We find that FIT subsidies significantly increase both the installed capacity and generation of PV and wind power.

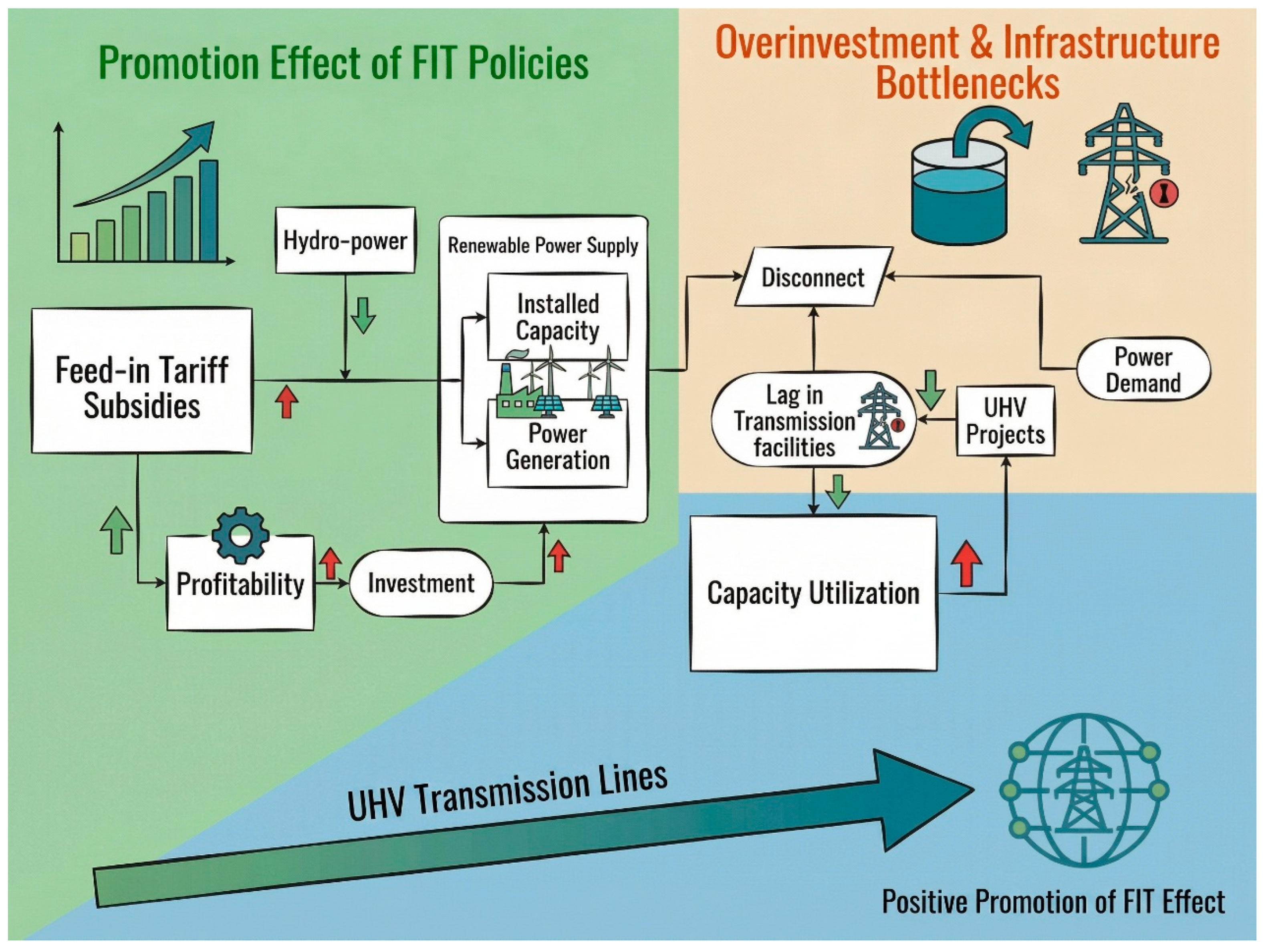

Further investigation shows that the FIT subsidy policy stimulates the development of the renewable energy industry by enhancing the likelihood of profitability for enterprises. However, the rigidity of fixed FIT subsidies can lead to decreases in capacity utilization rates, probably caused by overinvestment and insufficient public infrastructure for transmission lines. Also, hydropower has a crowding-out effect on photovoltaic and wind power generation, negatively impacting the effectiveness of FIT. The ultra-high-voltage (UHV) transmission project can help bridge the geographic mismatch between renewable energy supply and demand, thereby improving the efficiency of FIT implementation.

This study contributes both to the literature and policy practices on renewable energy development. First, with county-level data, we provide solid empirical evidence on the effectiveness of FIT subsidies, addressing gaps in the existing literature with data-driven evidence. Second, this study shows the two-sided effect of FIT subsidies, causing an increase in installed capacity and power generation, but a decrease in capacity utilization, which presents potential policy risks for governments when implementing fixed FIT subsidies. Third, by examining factors that influence the effectiveness of FIT subsidies, we provide valuable policy optimization suggestions.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 1 is the Introduction.

Section 2 is a brief literature review.

Section 3 shows the policy background.

Section 4 outlines the empirical strategies and presents the data sources used in the analysis.

Section 5 presents the empirical results and offers a discussion. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

This paper contributes to the literature on the impact of policy incentives on the growth of PV and wind power. While FIT is one of the most important policies in renewable energy development, research on its specific impact on PV and wind power is still limited. Most previous studies have primarily used data from specific regions, provincial levels, or publicly listed companies, which may lack precision and representativeness. For example, ref. [

4] use provincial panel data from 2012 to 2019 to study FIT’s effect on PV capacity, finding that a 0.1 yuan/kWh increase in PV subsidies leads to an additional 18 × 10

6 kW/year of national installed capacity. The authors of [

5] analyze data from Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, and Shaanxi provinces to explore how FIT affects regional disparities in new energy development, concluding that varying grid price subsidies contribute to uneven growth in wind and PV power across regions. The authors of [

6] examine data from publicly listed PV companies (2009–2015) to assess FIT’s impact on the sustainable development of China’s PV industry, finding that FIT policies significantly enhance inventory turnover and profitability. However, the use of data from specific regions, provincial levels, or publicly listed companies raises concerns about the precision and generalizability of these findings.

A similar trend is observed in studies on developed countries. The authors of [

7] assess the effectiveness of FIT policies in promoting PV and onshore wind power across 26 EU countries from 1992 to 2008, finding that FITs significantly drive PV development but have less impact on wind power. The authors of [

8] analyze data from 164 countries between 1990 and 2010 and conclude that feed-in tariffs are endogenous, with inconclusive impacts on renewable energy growth.

Due to the complexity of energy markets and the variety of factors influencing policy outcomes, some studies adopt modeling and simulation approaches. The authors of [

9] model the effects of environmental taxation and subsidization on wind and PV electricity, concluding that among policies such as FIT, Feed-in Premium, and Contracts for Difference, FITs have the greatest impact on investments in both wind and PV power. Similarly, ref. [

10] model the effects of fixed and premium FITs on wind turbine location choices, revealing that fixed FITs lead to higher balancing costs for intermittent energy production and fail to incentivize generation when marginal costs are high.

Overall, many of these empirical studies face limitations due to the precision of the data used. In contrast, this paper utilizes county-level data on renewable energy installation capacity and generation from all counties in China, offering greater representativeness and higher data quality. This comprehensive dataset enables us to draw more reliable conclusions about the impact of FIT on renewable energy development, addressing the gaps identified in prior research.

Several studies also examine other policy incentives for wind power and residential PV. For example, ref. [

11] investigates the impact of tax credits and production incentives on wind power expansion. Ref. [

12] evaluates the effect of upfront rebates in the California PV Initiative on residential PV installations, while ref. [

13] assesses the influence of government incentive programs on PV adoption. Ref. [

14] explores how financial rebates contribute to the growth of residential PV. More recent research compares different policies, such as investment versus output subsidies, on new energy development (e.g., [

15,

16]). These studies are also relevant to our article. Extending this literature, we find that the effectiveness of incentive policies is significantly influenced by regional natural resource endowments. Specifically, the same policy may yield very different outcomes depending on local wind, solar, or hydropower potential, suggesting that resource heterogeneity plays a crucial role in determining the impact of policy instruments.

Our article also addresses the issue of excess capacity in the renewable energy industry. Using modeling and numerical analysis, ref. [

17] shows that a ‘sticky’ feed-in tariff (FIT) coupled with falling wind power costs leads to high investor mark-ups and raises the risk of overinvestment in China. Other studies highlight that the intermittency of renewable energy sources and insufficient transmission capacity, which limit the balancing of supply and demand within the power system, are key contributors to excess capacity [

18,

19,

20]. Our findings demonstrate that the FIT subsidy policy boosts the probability of profitability for renewable energy enterprises, resulting in excessive incentives and an oversupply of renewable energy installations. This provides empirical evidence supporting the existence of excess capacity. Furthermore, our analysis reveals that the development of transmission infrastructure enhances the effectiveness of FIT policies and improves the capacity utilization rate of renewable energy systems. This provides new empirical evidence that complements and extends the existing literature.

3. Policy Background

In addition to tax incentives and reductions, the primary renewable energy subsidy policies implemented worldwide are the Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), Fixed Feed-in Tariff (FFIT), and Feed-in Tariff Bidding (FITB). The United States primarily implements RPS, which is a more voluntary policy, allowing local state governments to set renewable energy quota targets based on local conditions. Both FFIT and FITB are essentially forms of the FIT subsidy policy, but while the government sets the feed-in tariff under FFIT, FITB relies on market mechanisms to determine the tariff. The EU and China are the main regions implementing the FFIT system.

The FIT subsidy policy ensures that the government specifies the feed-in tariff for new energy electricity and mandates power companies to purchase all power generated by qualified new energy producers through subsidies. The purchase price is determined based on the production cost of each renewable energy technology, plus a certain profit margin. FIT contracts typically have a long-term duration of 10 to 20 years. During the contract period, renewable energy enterprises sell electricity to the grid at a higher price than the market rate, supported by government subsidies.

Since 2003, China has experimented with determining wind power prices through market-based subsidies, known as “concession bidding,” to gradually promote renewable energy development. Concession bidding involved the public tendering of one or more new energy projects by the government, with each power generation enterprise bidding to determine the feed-in price for the project. The resulting transaction prices from concession projects were generally lower than the approved wind power prices at the time, dropping as low as 0.38 yuan/kWh, approaching the benchmark feed-in price for thermal power. However, due to worsening pollution and increasing pressure from international climate negotiations, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) canceled the concession bidding policy for wind and PV power in 2009 and 2011, respectively. In its place, the NDRC introduced the Fixed Feed-in Tariff (FFIT) policy for both industries. Under this policy, power grids purchase renewable energy at the local benchmark price for thermal power, while the government subsidizes the difference between the fixed benchmark feed-in prices for renewable energy and thermal power.

To promote large-scale wind and PV power generation, the FFIT rates were set significantly higher than the previous concession project prices. China categorized the country into four wind energy resource zones and three PV energy resource zones, establishing specific FFIT rates for each zone. The FFIT rates for wind power in the four zones were set at 0.51 yuan, 0.54 yuan, 0.58 yuan, and 0.61 yuan per kWh, while for PV power, the rates were 0.9 yuan, 0.95 yuan, and 1.0 yuan per kWh in the three respective photovoltaic resource zones.

During this period, China’s installed capacity for wind and PV power entered a phase of rapid development. In 2009, China added 13.73 million kilowatts of new wind power capacity, surpassing the cumulative installed capacity of 9.65 million kilowatts from the previous two decades. Between 2009 and 2015, the annual growth rate of new wind power capacity averaged 47.5%, accounting for 42% of the global new capacity during this period. Similarly, in 2011, China added 2.7 million kilowatts of new photovoltaic capacity, far exceeding the cumulative total of 0.8 million kilowatts by the end of 2010. From 2011 to 2015, the average annual growth rate of new PV installations was 248%.

Many believe that the FFIT subsidy policy was instrumental in promoting the large-scale development of wind and PV power. However, it has also been cited as a key factor contributing to overcapacity in these sectors. Despite these views, there is limited empirical literature to substantiate such claims, and existing studies have not credibly quantified the elasticity between subsidies and renewable energy development. This gap largely stems from the lack of precise data, especially below the provincial or industry level, and the inability to construct explanatory variables that accurately quantify the regional impact of FIT policies.

This paper addresses these gaps by utilizing data from the China Power Industry Statistics Compilation Database to create a county-level dataset covering all installed PV and wind capacities. This allows for a more granular analysis of the FFIT’s impact on the development of China’s wind and PV power industries.

4. Empirical Strategy

To investigate the impact of the FIT on the development of the REPG industry, it is essential to utilize a high-quality dataset. Existing empirical studies on China’s renewable power generation industry often rely on data from provinces, specific regions, or publicly listed companies [

4,

5,

6]. However, provincial or regional data is typically not granular enough to support high-quality analysis. Moreover, there are concerns about the representativeness of sample data from listed companies, which may lead to selection bias and threaten the validity of empirical results.

To address these limitations, we construct a county-level dataset for China’s REPG industry using data from 2005 to 2017 from the Statistical Data Compilation of China Power Industry. This comprehensive dataset allows for more precise analysis, enabling us to leverage econometric tools effectively and conduct a more valid and accurate evaluation of FIT’s impact on the development of China’s REPG industry.

The following section introduces the empirical strategies, including model specifications, variable construction, and data sources used in our analysis.

4.1. Model Specification

4.1.1. Baseline Model

We begin by evaluating the impact of the FIT on the development of the REPG industry using a continuous Difference-in-Differences (DID) regression model. The model is specified as follows:

where

i denotes the county, and

t denotes the year.

is the explained variable, representing the installed capacity and power generation of PV or wind power at the county-year level.

, where

denotes province,

denotes year, and

denotes wind or PV power.

denotes the feed-in tariff (FIT) for renewable energy, and

represents the benchmark on-grid tariff for coal-fired power. In practice, local power companies purchase electricity generated from renewable sources at the coal benchmark price, while the difference between this price and the higher renewable FIT is covered by government subsidies. Accordingly, we define the relative subsidy level

, which indicates the level of FIT support relative to the local benchmark tariff for thermal power. Since the wind power feed-in tariff subsidy policy was implemented in 2009, we use the coal-fired power feed-in tariff of each province in 2009 as the benchmark feed-in price. Similarly, for the solar power feed-in tariff subsidy policy, which began in 2011, we use the coal-fired power feed-in tariff of each province in 2011 as the benchmark price.

represents a dummy variable indicating whether the policy has been implemented. If FIT is implemented in county

i, year

t, then

, otherwise,

= 0. Here,

is the interested causal effect of FIT on REPG industry. Since we employ log-form of the explained variable, every 10% increase of

causes

increase in the explained variable. Economically, it captures the percentage change in renewable energy installed capacity or generation associated with a one-unit increase in the relative FIT level compared to the benchmark on-grid price for coal-fired power.

represents a vector of county-year control variables, including GDP and the added value of the secondary industry, accounting for economic factors that influence renewable energy development, both of which are taken in logarithmic form. is the interaction term between wind speed or elevation and year, which controls for regional variations in renewable energy resource availability that may affect the development of the renewable energy industry. represents county fixed effects to control for time-invariant county characteristics. represents year fixed effects to account for common year-specific factors. is the error term. We cluster standard errors at the county level.

4.1.2. Event Study

The validity of the DID estimator hinges on the assumption that, in the absence of the FIT subsidy policy, the installed capacity and power generation trends in the treatment group would have followed the same trajectory as those in the control group. If this parallel trend assumption is violated, the differences between the two groups may not be attributable to the FIT subsidy policy, potentially leading to biased estimates. To assess whether this assumption holds, we employ an event study to examine the dynamic effects of the FIT subsidy policy over time. Specifically, the model is specified as:

where

represents the year.

indicates the year before policy introduction year as the omitted category to avoid collinearity. The coefficient

estimates the effect of the FIT subsidy policy at each point in time

, allowing us to assess the presence of any pre-treatment trends and to trace the dynamic evolution of the policy’s impact over time. Other terms are the same as in model (1).

4.1.3. Poisson Model

Since the resulting dependent variables are left-skewed and non-negative, we employ the Poisson Pseudo-Maximum Likelihood (PPML) estimator to replace model (1) [

21]. After the adjustment, the model becomes:

The main variables are the same as in model (1), where both the dependent and control variables are in absolute value form.

4.1.4. Other Model

We also aim to investigate whether the FIT subsidy policy affects the REPG industry through an economic channel. To do this, we employ a linear probability model specified as:

where

is the dependent variable, which is a dummy variable indicating the financial status of enterprise

i in year

t. If the profit or net profit is positive,

; otherwise,

.

is the interaction term, identical to model (1), representing the impact of the FIT subsidy policy on the county where enterprise

i is located.

is a matrix of enterprise-level control variables, including selling expense, total fixed assets, employees, and age.

represents regional-year fixed effects that vary over time. We follow the method of [

22] and divide China into six regions: North China, Northeast China, East China, Central and South China, Southwest China, and Northwest China. Region-year fixed effects are controlled to account for regional differences.

and

represent year and firm fixed effects, respectively.

is the error term.

4.2. Variable Description and Data Source

Explained variables. The two dependent variables are the installed capacity and electricity generation of wind and PV power. The data is manually compiled from the Statistical Data Compilation of China Power Industry. The data compilation records China’s power generation enterprises that own generator unit with capacity more than 6000 kW, including the information on the number of generator units, the unit installed capacity, power generation, utilization hours, and consumption for both power generation and supply. We traversed each power generation enterprise and its power generators, and attained the location and installation date of all installed capacities. Then the capacity and power generation data were summed up to the county-year level based on the location and installation date. Eventually, we generated a database of the installed capacity and power generation for the PV and wind power generation industry in each county of China from 2005 to 2017. The explained variables are subtracted from this database.

Explanatory variable. The explanatory variable is the relative FIT subsidy degree for wind and PV power. Under the FIT system, power companies purchase wind and PV electricity at the local thermal power benchmark price, while the government subsidizes the difference between this benchmark and the fixed FIT for wind/PV power. The greater the subsidy difference, the stronger the incentive for REPG participants to invest in additional capacity. We measure this incentive by calculating the ratio of the FIT subsidy difference to the thermal power benchmark price. This allows us to study how varying subsidy levels across regions affect the development of REPG.

Control variables. The control variables include both county-level GDP and secondary industry added value. These variables are sourced from the China County Statistical Yearbook. Due to severe data gaps in this yearbook, we only selected these two relatively complete variables. Additionally, regional differences in PV and wind resource endowments can lead to variations in the potential, development level, and trends of the REPG industry. To account for such factors, we used high-resolution WorldClim data to obtain information such as average altitude and average wind speed from 1970–2020 for each county in China.

Other variables. The financial data of REPG enterprise is derived from the Chinese tax survey database. We retained enterprises with observations before and after FIT implementation, and obtained a total of 507 observations from 512 wind power enterprises and 402 observations from 190 PV power enterprises. The sample data mainly includes total profit, net profit, employee count, selling expense, total fixed assets, and the establishment duration.

During the sample period 2005–2017, 611 and 975 counties installed wind and PV power generators, respectively. The remaining counties had no new energy power generation capacity. The summary statistics are shown in

Table 1.

5. Empirical Results and Analysis

5.1. Baseline Results

The primary goal of the FIT subsidy policy is to foster the development of the REPG industry. To assess the effectiveness of the FIT subsidy policy in China, we first apply the DID model specified in Model (1) to evaluate the policy’s impact on installed capacity and power generation for both PV and wind energy.

Table 2 presents the regression results.

Columns (1) and (2) of Panel A are the regression results on the installed capacity of wind power, and columns (3) and (4) are the regression results on wind power generation amount. Columns (1) and (3) are regression results that only control for county fixed effect and year fixed effect. The coefficients of the explanatory variable are significantly positive (p < 0.01), which indicates that a 10% increase in relative subsidy causes an increase of 24.33% in the installed capacity of wind power, and a 19.33% increase in wind power generation. In columns (2) and (4), we added control variables of the county-level GDP and added value to secondary, the coefficients are robustly significant (p < 0.01), indicating that a 10% increase in relative subsidy causes an increase of 25.87% in installed capacity of wind power, and a 20.28% increase in wind power generation.

Panel B is the regression results on the installed capacity and power generation of PV energy. Similarly to panel A, columns (1) and (3) are regression results that only control for county fixed effect, year fixed effect, and the interaction term of wind speed and year. The coefficients of the explanatory variable are also significantly positive (p < 0.01), indicating that a 10% increase in relative subsidy for PV FIT causes an increase of 19.80% in installed capacity of PV power, and a 15.50% increase in PV power generation. Columns (2) and (4) include extra controls for county-level GDP and added value to the secondary industry. The estimated results are robustly significant (p < 0.01), with a slight increase in effect magnitude.

These results suggest that FIT subsidies significantly boost both the installed capacity and generation of wind and PV power. Note that the dataset includes only generator units with a capacity of 6 MW or more, so small distributed PV systems and micro wind installations are not captured. A reasonable assumption is that these small units are subject to the same FIT subsidy effects. As a result, while the impact of FIT subsidies on renewable generation may be underestimated, the overall conclusion remains unchanged.

5.2. Dynamic Effects Test

In this section, model (2) is used to examine the dynamic effects of FIT on the installed capacity and power generation amount of regional wind and PV power.

Figure 1 shows the corresponding results.

Figure 1a,b plot the dynamic effect on the installed capacity and power generation amount of wind power. The dynamic effects prior to the implementation year of the FIT are not significantly different from zero, indicating no significant differences in installed capacity and power generation in the wind power industry between the various exposure groups. After the implementation year of FIT, the dynamic effects become robustly positive and significant, which validates the conclusions drawn from the results of model (1).

The same situation is observed from

Figure 1c,d, which show the dynamic effects of FIT on the installed capacity and power generation amount of the PV power industry. Also, the parallel trend hypothesis is satisfied for PV power, and the conclusions drawn from the results of model (1) stand for PV power. It should be noted, however, that, for the sake of maintaining the sample size, we only controlled for GDP and Secondary GDP, which may raise concerns that regional economic or policy heterogeneity is not fully captured. Therefore, in

Appendix A Table A1, we also include additional county-level control variables, showing that this concern does not materialize: the effects remain significant, although the sample size decreases substantially.

In short, the above results show that the parallel trend hypothesis of the benchmark regression model is valid, and the increase in installed capacity and power generation amount of the REPG industry is indeed caused by the FIT.

5.3. Robustness Check

To further test the reliability of the baseline results, this section conducts a series of robustness checks.

5.3.1. Poisson Regression

First, since the distribution of the outcome variables of interest is left-biased and non-negative, we further employ the Poisson-pseudo-maximum likelihood method to examine the effect of FIT subsidy policy on REPG industry development via the model (3).

Table 3 shows the regression results. Panel A shows the regression results on the wind power generation industry. Columns (1) and (2) are the regression results on the installed capacity and power generation for wind power, and columns (3) and (4) are the regression results for PV power. By using e

β−1 to convert the estimated coefficients into proportional form, it can be obtained that a 10% increase in relative subsidy causes the installed capacity and power generation amount of wind energy to increase by 23.4% and 14.6%, the magnitudes of which are close to the baseline model results. Similarly, the results for PV energy in columns (3) and (4) are also robust.

5.3.2. Linear Probability Regression

Second, a linear probability estimation is employed to test the FIT’s effect on the probability of a county achieving REPG industry development. To construct the linear probability model, we keep the other settings of models (1) the same, but substitute the explained variables with a dummy variable. The new explained variable equals 1 when the county owns wind/PV power installed capacity or power generation amount greater than 0, and equals 0 otherwise. Then, a linear probability model is produced to examine whether FIT causes a greater probability of the county adding new installed capacity or generating power in the wind/PV power industry.

Table 4 shows the results. The coefficients of the policy explanatory variable in columns (1)–(4) are all significantly positive (

p < 0.01 for columns (1)–(3), and

p < 0.05 for column (4)). The regression results show that the FIT does cause a higher probability of increasing the installed capacity and power generation amount of the wind/PV power industry in the processing county. Moreover, the effect on the PV power industry is even higher than that on the wind power industry from the magnitude of the coefficient.

5.3.3. Potential Confounders

Third, since the electricity supply industry is subject to various environmental regulatory policies, which may drive the development of wind and PV industries, it is possible that the observed effects in this paper stem from these regulatory policies rather than the FIT subsidy policy. To rule out these confounding factors, we consider two potential confounders.

The first factor is the “Green” dispatch pilot policy. This policy, aimed at energy-saving and emission-reducing dispatch, was piloted in five provinces (Guangdong, Guangxi, Yunnan, Guizhou, and Hainan) starting in 2010. The results observed in this paper could potentially be driven by this policy. We test the effect of this policy by adding a dummy variable, Green dispatch, indicating this policy.

Table 5 columns (1)–(2) show the results that our conclusion is not affected.

The second factor is the intensity of environmental regulation. Given that China’s electricity supply industry relies heavily on coal-fired power generation, which causes significant environmental pollution, regions with higher coal consumption may face stricter environmental regulations, leading to faster development of wind and PV power. Therefore, we measure the environmental regulation intensity at the county level using the coal consumption data for power generation in each county to test the influence of this factor. We compiled coal consumption data from the Compilation of Statistics on the Power Industry. The regression results, shown in

Table 5, columns (3)–(4), indicate that our conclusions are also not driven by this factor. These tests confirm the reliability of our baseline regression results.

5.4. Enterprise Profitability

The analyses above provide strong evidence that the FIT subsidy for REPG does increase both the installed capacity and power generation of the wind and PV industries. However, given the Chinese government’s strong administrative capabilities, some policy outcomes may result from administrative influence rather than purely economic mechanisms. In theory, under FIT subsidy, the grid company is more willing to purchase Renewable energy power at the benchmark feed-in tariff higher than coal-fired power. This arrangement accelerates the capital return for enterprises, effectively reducing the early investment and installation costs for wind and PV power firms [

9,

18]. This economic mechanism should be reflected in the profitability of REPG enterprises. To verify whether the FIT achieves its intended economic mechanism, we examine the effect of the FIT subsidy policy on the profitability of REPG enterprises. This will help determine whether the policy’s impact on profitability aligns with the theoretical expectations of capital return and cost reduction. Thus, model (4) is employed here, and the results are shown in

Table 6.

The results show that every 10% increase in the relative FIT subsidy for PV power will cause the probability of PV power generation enterprises gaining positive net profit and positive gross profit to increase by 6.43% and 8.62%, respectively. Every 10% increase in the relative FIT subsidy for wind power will cause the probability of wind power generation enterprises gaining positive net profit and positive gross profit to increase by 13.36% and 11.48%, respectively. This supports that the effect of FIT on REPG industry development is achieved through an economic mechanism.

5.5. Capacity Utilization Rate

The analysis above demonstrates that the primary mechanism by which the FIT subsidy promotes the development of the REPG industry is by increasing the profitability of enterprises. However, the fixed nature of the FIT subsidy creates inflexibility, and significant delays in adjusting subsidy policies can lead to over-incentivizing market participants. This, in turn, encourages excessive investment in wind and PV power generation [

10,

17]. Consequently, the inability to efficiently adapt subsidy levels to market conditions may contribute to overcapacity and inefficiencies in the renewable energy sector.

Additionally, transmission constraints, particularly the poor transmission infrastructure between wind- and PV-rich areas and the demand centers, can hamper the effective integration of renewable energy into the grid. These constraints, alongside the intermittent nature of renewable sources, limit the full utilization of installed capacity [

18,

19,

20]. Consequently, this combination of overcapacity from excessive investment and underutilization due to transmission and natural constraints may lower the capacity utilization rate of wind and PV energy generation equipment.

To verify this judgment, we use the ratio of wind and PV energy generation to installed capacity in each county to measure the capacity utilization rate of renewable energy equipment. Then, we examine the effect of the FIT subsidy on capacity utilization, with the regression results presented in

Table 7. The results indicate that the FIT subsidy indeed reduces the capacity utilization rate of wind and PV power.

5.6. Resource Endowment

Many southern regions in China are rich in hydropower resources, where hydropower is well developed, and the on-grid electricity price is relatively lower than that of coal-fired power. As a result, even with support from FIT policies, wind and solar power may not enjoy a significant cost advantage over hydropower. Consequently, the effectiveness of the FIT subsidy policy in promoting wind and solar development may be limited in these regions. To account for this, we examine the role of regional resource endowments. Since hydropower development is inherently constrained by the geographical distribution of water resources, we divide China into two regional groups based on the 2012 share of hydropower in total electricity generation. Regions where hydropower accounted for the largest share among all generation sources are classified as “Water-rich Regions,” while all other regions are grouped separately (The Water-rich Regions comprise: Beijing Municipality, Tianjin Municipality, Chongqing Municipality, Yunnan Province, Hunan Province, Sichuan Province, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Jiangxi Province, Guizhou Province, Tibet Autonomous Region, and Qinghai Province). Using this classification, we empirically investigate the heterogeneous impacts of the FIT subsidy policy across regions, offering a more nuanced foundation for policy formulation.

The detailed regression results are presented in

Table 8. Panel A reports the findings for photovoltaic (PV) power, where columns (1)–(3) correspond to water-rich regions and columns (4)–(6) to other regions. The results indicate that in regions with abundant hydropower resources, the effect of the FIT subsidy policy is statistically insignificant, whereas in other regions, the policy shows a strong and significant positive impact. Similar patterns are observed in Panel B, which presents the results for wind power.

These findings suggest that FIT policies should be implemented selectively, taking regional resource endowments into account to maximize their effectiveness. From the perspective of clean energy transition, this implies that regions with rich hydropower resources should continue to prioritize hydropower development, while in areas with abundant solar and wind potential, FIT subsidies can be more effectively leveraged to support the expansion of renewable electricity. A regionally differentiated policy approach would thus be more conducive to accelerating the clean energy transition.

5.7. Ultra-High Voltage

Given that regions with abundant renewable energy resources—such as Northwest and North China—are geographically distant from the country’s major economic centers located in the eastern coastal areas, there exists a significant spatial mismatch between renewable electricity supply and demand. In the context of underdeveloped electricity storage technologies, transmission networks play a crucial role in bridging this gap by linking generation-rich areas with high-demand regions, thereby facilitating the development of the renewable power sector. In this section, we further examine how the construction of transmission infrastructure influences the effectiveness of FIT policies.

We conducted an analysis of Ultra-High-Voltage (UHV) transmission projects and their influence on the relationship between Feed-in Tariffs (FIT) and photovoltaic (PV) power generation (All UHV projects during the sample period are obtained from publicly available documents, and the detailed list is provided in

Appendix A Table A4). The results are presented in

Table 9, Panel A. Specifically, columns (1) to (3) show that UHV transmission projects significantly increase the installed capacity and power generation of PV, and also enhance the capacity utilization rate of PV systems. Columns (4) to (6) further examine how UHV projects affect the effectiveness of the FIT subsidy policy. The results indicate that in regions where UHV projects have been implemented, the FIT subsidy policy has a significantly more positive impact on PV installed capacity and generation. This suggests that UHV, by connecting electricity supply and demand across regions, can strengthen the effect of FIT policies on PV development.

In

Table 9, Panel B, we examine the impact of Ultra-High-Voltage (UHV) transmission projects on the relationship between Feed-in Tariffs (FIT) and wind power generation. The results are presented in columns (1) to (6). Specifically, columns (1) to (3) show that UHV transmission projects significantly increase both the installed capacity and electricity generation of wind power, while also improving its capacity utilization rate. Columns (4) to (6) explore the role of UHV in influencing the effectiveness of the FIT subsidy policy. The results indicate that in regions where UHV projects have been implemented, the FIT subsidy policy has a notably stronger positive impact on wind power development. This suggests that by facilitating the transmission of electricity across regions, UHV infrastructure helps to amplify the effect of the FIT on wind energy production.

Therefore, we find that UHV transmission projects can amplify the relationship between FIT policies and renewable electricity development. The underlying mechanism lies in the ability of UHV infrastructure to connect renewable generation sites with major consumption centers, thereby expanding the potential for renewable energy deployment and more efficiently driving the growth of the new energy sector.

6. Conclusions

While FIT has been the dominant policy in promoting the development of the New Energy Power Generation industry in leading countries, the causal effect between FIT and the development of the REPG industry has not been solidly validated due to a lack of precise and non-biased data. This study takes China’s FIT subsidy policy as an example, employing county-level observations in the REPG industry, and proves via the DID method and a series of robustness checks that the FIT subsidy policy during 2009–2017 does cause a large increase in both the installed capacity and power generation amount in the REPG industry, including both PV and wind power. Our study contributes new and solid empirical evidence on the causal effect between FIT and REPG industry development, especially making up for the low data precision and challenge from the potentially biased sample of current studies herein. With further channel exploration, the results indicate that the promotion effect is achieved through the economic channel because FIT significantly increases REPG enterprise’s profitability. Also, we verified the causal effect that FIT decreases the capacity utilization rate, possibly because excessive subsidies brought by the FIT subsidy policy will lead enterprises to rapidly build new capacity regardless of regional demand, power supply infrastructure level, and other factors, and finally lead to a decline in capacity utilization.

The results of our paper have several applications. First, the findings indicate that the feed-in tariff subsidy policy promotes the development of the renewable energy generation industry by improving the profitability of renewable energy companies. Therefore, it is essential to maintain the feed-in tariff subsidy policy until the renewable energy sector can achieve profitability without relying on government support. Second, the policy has led to excessive incentives for participants in the renewable energy industry, resulting in underutilization of production capacity. To address this, the feed-in tariff subsidy policy should be flexibly adjusted to adapt to changing market conditions, ensuring that it can better fulfill its role. Third, based on our analysis, one key reason for the underutilization of capacity is inadequate transmission line infrastructure between generation and consumption points. Therefore, to ensure the healthy development of the renewable energy sector, it is crucial to strengthen the construction of transmission lines and the development of energy storage systems. Finally, to effectively support the clean energy transition in the power sector, the implementation of FIT policies should be tailored to regional resource endowments. In areas rich in solar and wind resources, FIT subsidies can effectively accelerate the deployment of renewable electricity. However, in regions abundant in hydropower resources, it may be more appropriate to prioritize the development of hydropower rather than promoting wind and solar energy. A region-specific policy approach will help maximize the effectiveness of renewable energy promotion strategies.

Beyond these policy implications, the findings of this study also have broader relevance for sustainable development. This study also contributes to the broader discussion on sustainable development. By providing causal evidence on how FIT subsidies influence renewable electricity deployment, profitability, and system efficiency, our findings highlight both the opportunities and challenges of policy-driven energy transitions. FIT subsidies are shown to be a key driver of clean electricity expansion, supporting China’s transition toward a low-carbon and sustainable power system. However, rigid and excessive subsidies may lead to resource misallocation and lower utilization efficiency, raising concerns about long-term sustainability. Therefore, a more flexible, regionally differentiated, and infrastructure-coordinated FIT design can reduce waste, enhance system reliability, and promote a more sustainable energy future. These insights offer useful guidance for policymakers aiming to design efficient and environmentally sustainable renewable energy policies.