How Household Characteristics Drive Divergent Livelihood Resilience: A Case from the Lancang River Source Area of Sanjiangyuan National Park

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

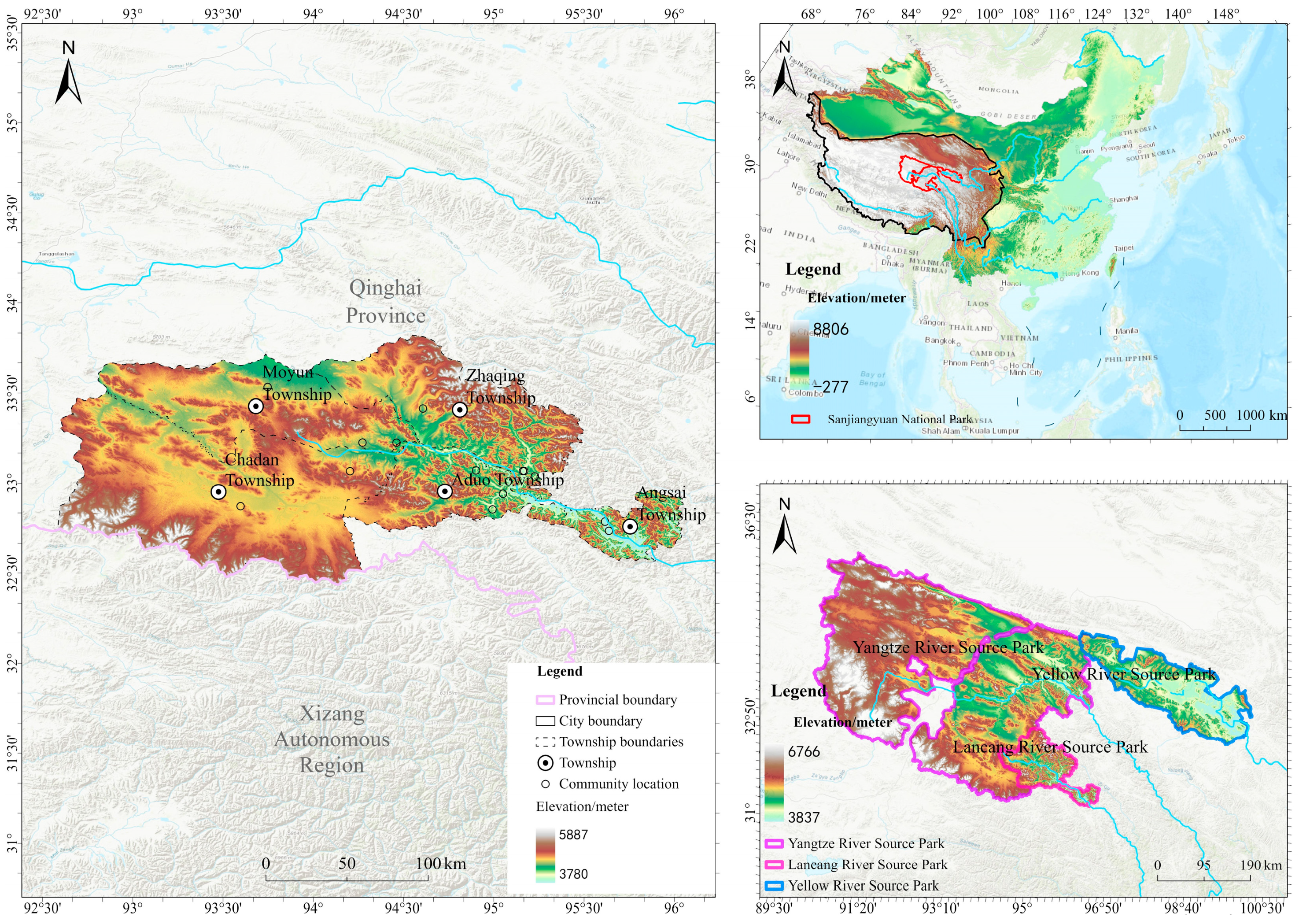

2.1. Study Area and Livelihoods of Herders

2.2. Data Source

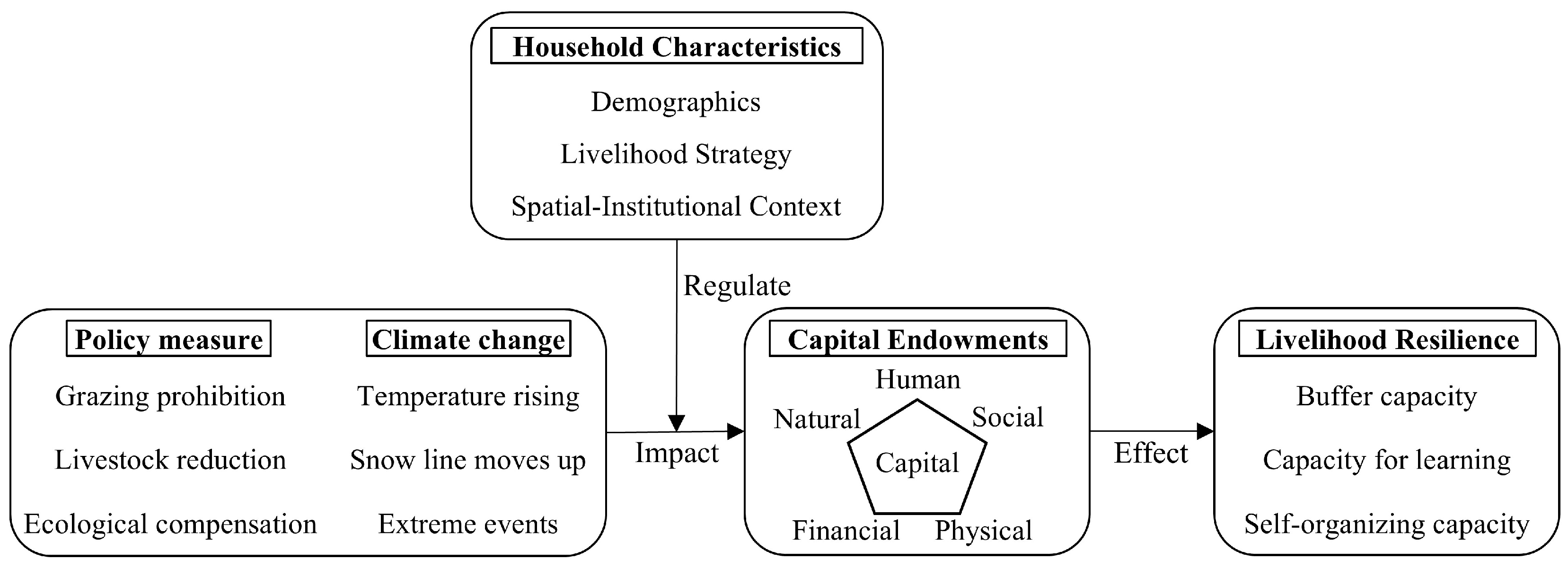

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Indicator System

- (1)

- Data standardization

- (2)

- Determination of Indicator Weights

- (3)

- Comprehensive Evaluation Using the TOPSIS Model

2.3.2. Analysis of Influencing Factors

2.3.3. Moderation Effect Measure

2.3.4. Robustness Testing Strategy

3. Results

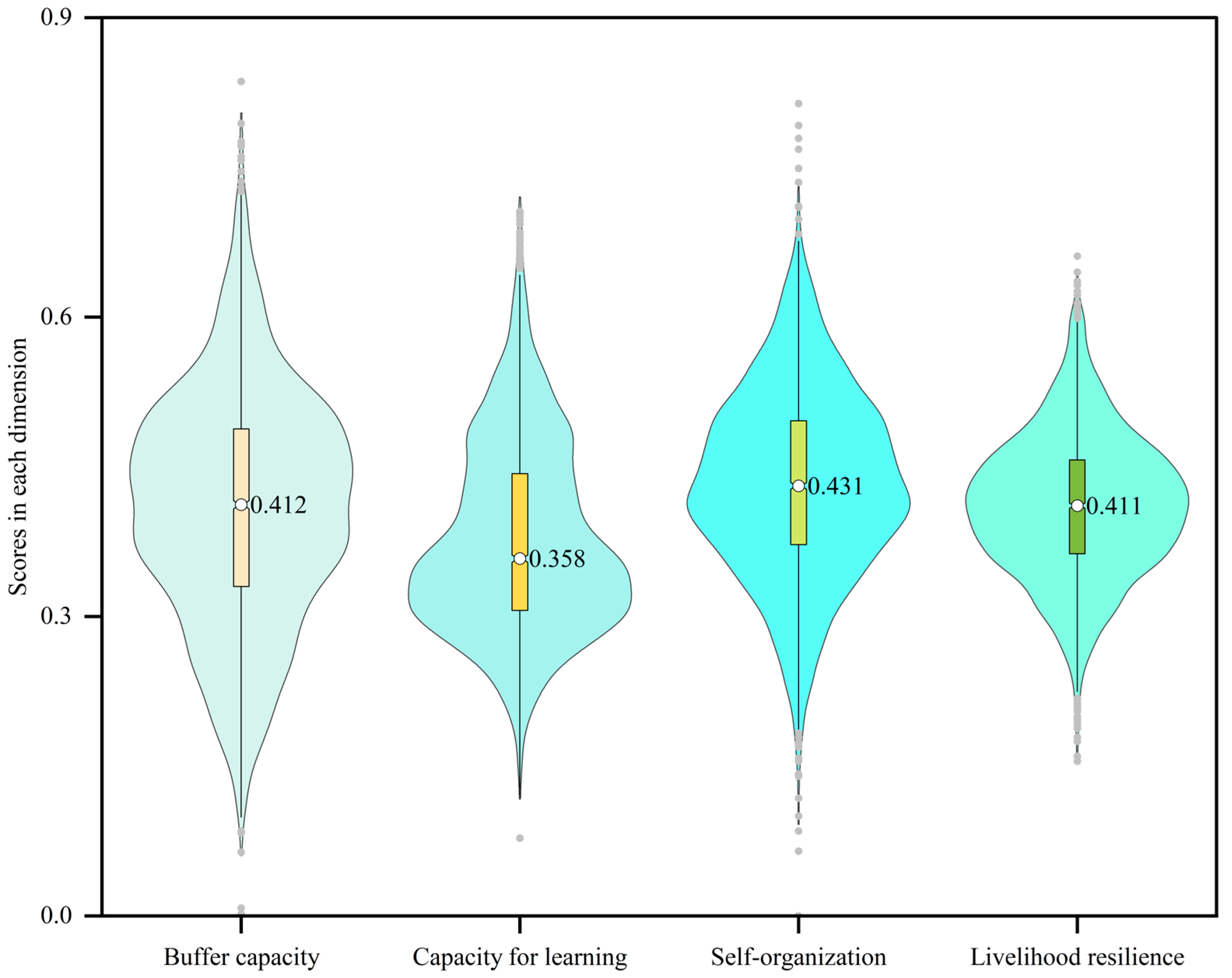

3.1. Livelihood Resilience Assessment Results

3.1.1. Composition of Household Resilience

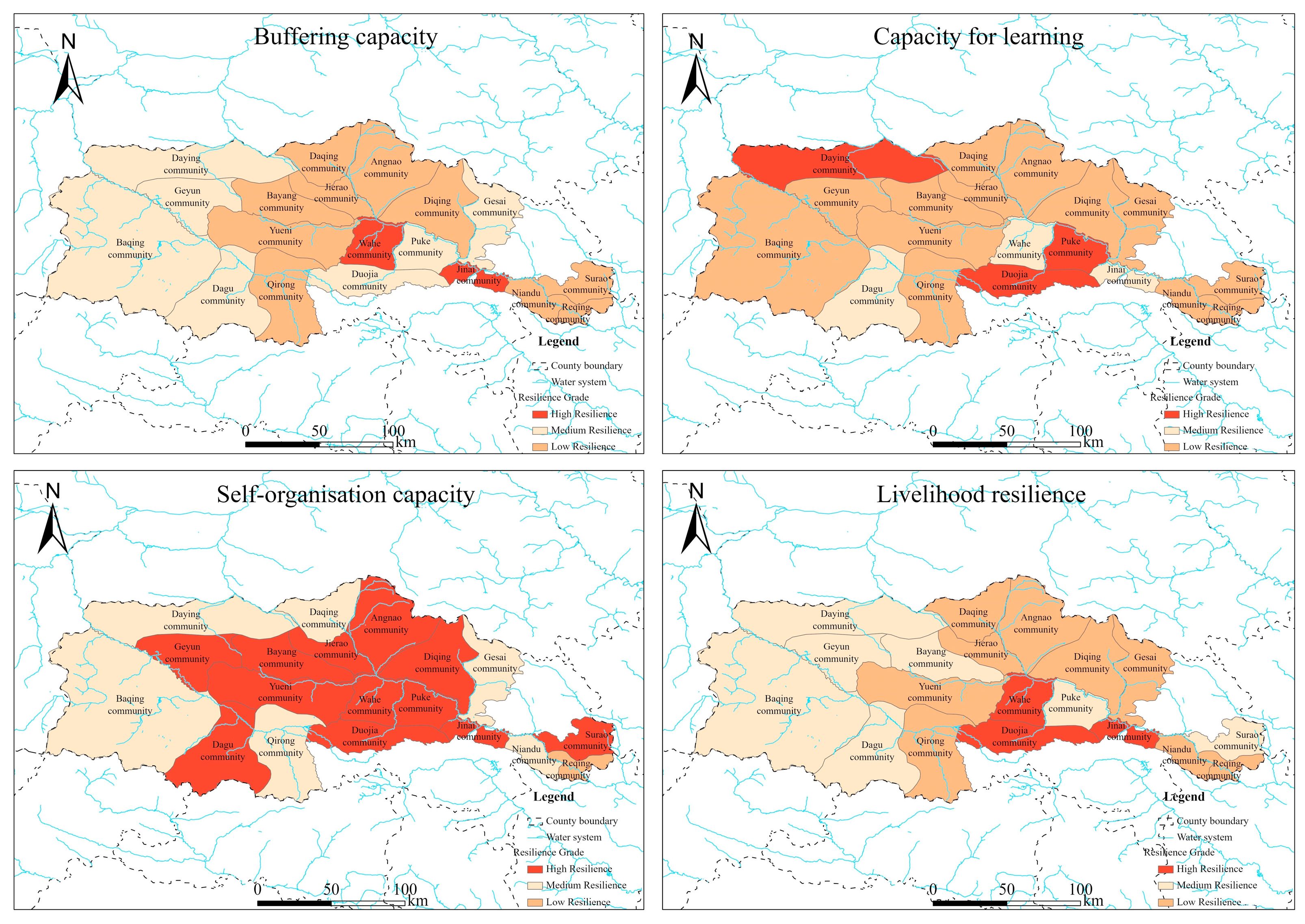

3.1.2. Village Clusters and Spatial Patterns

3.2. Results of Influencing Factor Evaluation

3.2.1. Identification of Influencing Factors

3.2.2. Results of Spatial Effect Analysis

3.3. Results of the Moderation Effect Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Gender and Life Cycle Shape Intervention Response Pathways

4.2. Policy Environment and Livelihood Choices Collaboratively Construct Resilience

4.3. Spatial Patterns of Resilience as Influenced by Household Heterogeneity

4.4. Robustness Assessment and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piemontese, L.; Terzi, S.; Di Baldassarre, G.; Menestrey Schwieger, D.A.; Castelli, G.; Bresci, E. Over-Reliance on Water Infrastructure Can Hinder Climate Resilience in Pastoral Drylands. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugjamba, N.; Walkerden, G.; Miller, F. Adapting Nomadic Pastoralism to Climate Change. Clim. Change 2023, 176, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, G.; Guo, J.; Lei, Y.; Su, Y. Ecological Sustainability: A “Natural-Social-Digital” Analysis Framework for China’s National Park Policy. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 391, 126400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Kong, D.; Wu, C.; Moller, A.P.; Longcore, T. Predicted Effects of Chinese National Park Policy on Wildlife Habitat Provisioning: Experience from a Plateau Wetland Ecosystem. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 115, 106346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risvoll, C.; Hovelsrud, G.K.; Riseth, J.A. Falling between the Cracks of the Governing Systems: Risk and Uncertainty in Pastoralism in Northern Norway. Weather Clim. Soc. 2022, 14, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Shen, Y.; Dong, S.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Wan, L.; Liu, G. Feedback and Trigger of Household Decision-Making to Ecological Protection Policies in Sanjiangyuan National Park. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 827618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Xia, F.; Chen, Q.; Huang, J.; He, Y.; Rose, N.; Rozelle, S. Grassland ecological compensation policy in China improves grassland quality and increases herders’ income. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Dong, S.; Dong, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhi, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhao, X. Trade-offs in ecological, productivity and livelihood dimensions inform sustainable grassland management: Case study from the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 313, 107377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Singh, R.K.; Pandey, R.; Liu, H.; Cui, L.; Xu, Z.; Xia, A.; Wang, F.; Tang, L.; Wu, W.; et al. Enhancing sustainable livelihoods in the Three Rivers Headwater Region: A geospatial and obstacles context. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, X.; Feng, X. Livelihood resilience of vulnerable groups in the face of climate change: A systematic review and meta-Analysis. Environ. Dev. 2022, 44, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, C.I.; Wiesmann, U.; Rist, S. An indicator framework for assessing livelihood resilience in the context of social–ecological dynamics. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 28, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, T.D. Pastoralist Livelihood Diversification and Social Network Transition: A Conceptual Framework. Pastor.-Res. Policy Pract. 2024, 14, 12892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, A.E.; Berbes-Blazquez, M.; Haider, L.J.; Peterson, G.D. Measuring and assessing resilience: Broadening understanding through multiple disciplinary perspectives. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ren, L.; Xu, J.; Li, C.; Li, S. Exploring Livelihood Resilience and Its Impact on Livelihood Strategy in Rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 977–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschinger, R.; Boillat, S.; Speranza, C.I. Smallholder livelihood resilience to climate variability in South-Eastern Kenya, 2012–2015. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1070083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Yang, X.; Sun, W. How do ecological vulnerability and disaster shocks affect livelihood resilience building of farmers and herdsmen: An empirical study based on CNMASS data. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 998527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansah, I.G.K.; Gardebroek, C.; Ihle, R. Resilience and household food security: A review of concepts, methodological approaches and empirical evidence. Food Secur. 2019, 11, 1187–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.; Meerow, S.; Arnott, J.; Jack-Scott, E. The turbulent world of resilience: Interpretations and themes for transdisciplinary dialogue. Clim. Change 2019, 153, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, A.; Paderes, P. Livelihood resilience and global environmental change: Toward integration of objective and subjective approaches of analysis. Geogr. Rev. 2023, 113, 536–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; Zhang, P.; Yu, H.; Zhang, N.; Liu, Y. Analysis on Coupling Coordination Degree Between Livelihood Strategy for Peasant Households and Land Use Behavior in Ecological Conservation Areas—A Case Study of the Chang-Zhu-Tan Ecological Greenheart Area. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guodaar, L.; Kabila, A.; Afriyie, K.; Segbefia, A.Y.; Addai, G. Farmers’ Perceptions of Severe Climate Risks and Adaptation Interventions in Indigenous Communities in Northern Ghana. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 95, 103891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, D.B.; Scholz, R.W. Community-Based Ecotourism in Bhutan: Expert Evaluation of Stakeholder-Based Scenarios. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2008, 15, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, K.; Valdivia, C.; Slayback, D.; Jimenez, E.; Meneses, R.I.; Palabral, A.; Bracho, M.; Romero, D.; Hubbard, A.; Pacheco, P.; et al. Socio-Ecological Dimensions of Andean Pastoral Landscape Change: Bridging Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Satellite Image Analysis in Sajama National Park, Bolivia. Reg. Environ. Change 2019, 19, 1353–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreavy, B. Resilience as Discourse. Environ. Commun. 2016, 10, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, W.; Xiong, L.; Wang, F. Is There an Environment and Economy Tradeoff for the National Key Ecological Function Area Policy in China? Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 104, 107347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yan, J.; Akin, S.-M.; Liu, H.; Martens, P. Livestock Diversification Works as a Helpful Livelihood Strategy for Herders on the Tibetan Plateau: Implications for Climate Change Adaptation. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 101116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, D.; Fan, J. Sustainable Development Problems and Countermeasures: A Case Study of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Swallow, B.; Zhong, L.; Xu, K.; Sang, W.; Jia, L. Local Perspectives on Social-Ecological Transformation: China’s Sanjiangyuan National Park. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 26, 1809–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, X. Study on the Coordinated Development of Economy, Tourism, and Eco-Environment in Sanjiangyuan. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 9463166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohidimoghadam, A.; PourSaeed, A.; Bijani, M.; Samani, R.E. Towards farmers’ livelihood resilience to climate change in Iran: A systematic Review. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 19, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavatassi, R.; Phillips, L.M.; Maggio, G.; Anteneh, Z.; Mabiso, A. Enhancing households’ livelihoods in agrifood systems: The role of women’s Empowerment. Glob. Food Secur. 2025, 45, 100856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.U.; Dulal, H.B.; Johnson, C.; Baptiste, A. Understanding livelihood vulnerability to climate change: Applying the livelihood vulnerability index in Trinidad and Tobago. Geoforum 2013, 47, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, S.; Zibaei, M.; Keshavarz, M. The Effectiveness of Livelihood Management Strategies in Mitigating Drought Impacts and Improving Livability of Pastoralist Households. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 77, 103063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, H.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wan, L.; Yang, S.; Liu, G.; Su, X. The Role of Livelihood Assets in Livelihood Strategy Choice from the Perspective of Macrofungal Conservation in Nature Reserves on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 44, e02478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, M.; Jin, B.; Yao, L.; Ji, H. Does Livelihood Capital Influence the Livelihood Strategy of Herdsmen? Evidence from Western China. Land 2021, 10, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Lü, D.; Wang, C.; Lü, Y.; Wu, X. Spatiotemporal Patterns and Driving Factors of Ecological Vulnerability on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Based on the Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Ma, Y.; Xue, Y.; Piao, S. Climate Change Trends and Impacts on Vegetation Greening Over the Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 2019, 124, 7540–7552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Shi, B.; Su, G.; Lu, Y.; Li, Q.; Meng, J.; Ding, Y.; Song, S.; Dai, L. Spatiotemporal analysis of ecological vulnerability in the Tibet Autonomous Region based on a pressure-state-response-management framework. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 130, 108054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, D.; Hao, H. The dominant livelihood types of farm households and their determinants in Key Ecological Function Areas. J. Resour. Ecol. 2022, 14, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, O.J.; Rayamajhi, S.; Uberhuaga, P.; Meilby, H.; Smith-Hall, C. Quantifying rural livelihood strategies in developing countries using an activity choice Approach. Agric. Econ. 2013, 44, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Gan, C. The nexus between livelihood goals and livelihood strategy selection: Evidence from rural China. Appl. Econ. 2023, 56, 5012–5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Phuoc, D.Q.; Nguyen, N.A.N.; Tran, P.T.K.; Pham, H.-G.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. The influence of environmental concerns and psychosocial factors on electric motorbike switching intention in the global south. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 113, 103705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Zhu, C.; Li, Y.; Sun, W.; Li, J. Factors Influencing Livelihood Resilience of Households Resettled from Coal Mining Areas and Their Measurement—A Case Study of Huaibei City. Land 2024, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Bai, Y.; Fu, C.; Xu, X.; Sun, M.; Cheng, B.; Zhang, L. Heterogeneous Effects of Skill Training on Rural Livelihoods around Four Biosphere Reserves in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonye, S.Z.; Aasoglenang, T.A.; Yiridomoh, G.Y. Urbanization, agricultural land use change and livelihood adaptation strategies in peri-urban Wa, Ghana. SN Soc. Sci. 2020, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimengsi, J.N.; Pretzsch, J.; Kechia, M.A.; Ongolo, S. Measuring Livelihood Diversification and Forest Conservation Choices: Insights from Rural Cameroon. Forests 2019, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviedes, J.; Ibarra, J.T.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Alvarez-Fernandez, S.; Junqueira, A.B. Indigenous and local knowledge on Social-ecological changes is positively associated with livelihood resilience in a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System. Agric. Syst. 2024, 216, 103885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, O.; Li, X.; Reyes-Garcia, V. Exploring the dynamic functions of pastoral traditional Knowledge. Ambio 2025, 54, 932–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abunyewah, M.; Erdiaw-Kwasie, M.O.; Okyere, S.A.; Thayaparan, G.; Byrne, M.; Lassa, J.; Zander, K.K.; Fatemi, M.N.; Maund, K. Influence of personal and collective social capital on flood preparedness and community resilience: Evidence from Old Fadama, Ghana. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 94, 103790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wu, Y.; Wei, J. The Status of Collective Action among Rural Households in Underdeveloped Regions of China and Its Livelihood Effects under the Background of Rural Revitalization—Evidence from a Field Survey in Shanxi Province. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y. Measurement of livelihood resilience and its influencing factors for farmers in poverty alleviation areas: A case study of Yunnan Province, China. Appl. Econ. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroca-Jimenez, E.; Bodoque, J.M.; Garcia, J.A. An Integrated Multidimensional Resilience Index for urban areas prone to flash floods: Development and Validation. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 894, 164935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, P.; Wang, S.; Li, W.; Dong, Q. Urban resilience assessment based on “window” data: The case of three major urban agglomerations in China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 85, 103528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Cai, S.; Singh, R.K.; Cui, L.; Fava, F.; Tang, L.; Xu, Z.; Li, C.; Cui, X.; Du, J. Livelihood resilience in pastoral communities: Methodological and field insights from Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Tian, M.; Cheng, J.; Chen, W.; Zhao, Z. Environmental regulation and green energy efficiency: An analysis of spatial Durbin model from 30 provinces in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 67046–67062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, B.; Stoffelen, A.; Vanclay, F. Understanding resilience in ethnic tourism communities: The experiences of Miao villages in Hunan Province, China. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 32, 1433–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.K.; Yadav, M. Confidence Interval: Advantages, Disadvantages and the Dilemma of Interpretation. Rev. Recent Clin. Trials 2024, 19, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Lee, J.E. Exploring and Enhancing Community Disaster Resilience: Perspectives from Different Types of Communities. Water 2024, 16, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Qian, W.; Jiang, H. Spatial-temporal distribution and multiple driving mechanisms of energy-related CH4 emissions in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 106, 107463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L.; Zaccaria, L. From patriarchy to partnership: Gender equality and household finance. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 147, 573–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, S. Parental Investment, Status, and Child Gender: Some Evidence for the Trivers–Willard Hypothesis from a Survey Experiment. Kölner Z. Soziologie Sozialpsychologie 2024, 76, 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigussie, L.; Minh, T.T.; Senaratna Sellamuttu, S. Youth Inclusion in Value Chain Development: A Case of the Aquaculture in Nigeria. Cabi Agric. Biosci. 2024, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.; Balasubramanian, K.; Atieno, R.; Onyango, J. Lifelong learning to empowerment: Beyond formal Education. Distance Educ. 2018, 39, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, M.; Giblin, J.; Ciccone, M.; Davis, A.; Fuhrman, J.; Kimiaie, M.; Madzsar, S.; Olson, K.; Senn, M. Social Risk-Management Strategies in Pastoral Systems: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Cross-Cult. Res. 2011, 45, 286–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Nie, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Kang, Q.; Lei, W. How to improve the adaptive capacity of coastal zone farm households?—Explanation based on complementary and alternative relationships of livelihood capital in a sustainable livelihood framework. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 245, 106853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; He, S.; Min, Q.; Yang, X. Conflict or Coexistence? Synergies between Nature Conservation and Traditional Tea Industry Development in Wuyishan National Park, China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 6, 991847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zeng, X. From Land Conservation to Famers’ Income Growth: How Advanced Livelihoods Moderate the Income-Increasing Effect of Land Resources in an Ecological Function Area. Land 2025, 14, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-i-Gelats, F.; Contreras Paco, J.L.; Huilcas Huayra, R.; Siguas Robles, O.D.; Quispe Peña, E.C.; Bartolomé Filella, J. Adaptation Strategies of Andean Pastoralist Households to Both Climate and Non-Climate Changes. Hum. Ecol. 2015, 43, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapruwan, R.; Saksham, A.K.; Bhadoriya, V.S.; Kumar, C.; Goyal, Y.; Pandey, R. Household livelihood resilience of pastoralists and smallholders to climate change in Western Himalaya, India. Heliyon 2024, 10, 24133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Song, C.; Huang, H. Rural Resilience in China and Key Restriction Factor Detection. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banica, A.; Pascariu, G.C.; Kourtit, K.; Nijkamp, P. Unveiling Core-periphery disparities through multidimensional spatial resilience Maps. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2024, 73, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yuan, C.; Liao, T. The Spatial Spillover Effects of Fiscal Expenditures and Household Characteristics on Household Consumption Spending: Evidence from Taiwan. Economies 2022, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Xu, X. Community-level Social Capital and Agricultural Cooperatives: Evidence from Hebei, China. Agribusiness 2021, 37, 804–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoop, E.; Brandsen, T.; Helderman, J.-K. The impact of the cooperative structure on organizational social capital. Soc. Enterp. J. 2021, 17, 548–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Wang, X.; Nisar, U.; Sun, S.; Ding, X. Mechanisms and Heterogeneity in the Construction of Network Infrastructure to Help Rural Households Bridge the “Digital Divide”. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Township | Village | Valid Samples (Households) | Total (Households) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zhaqing | Diqing | 301 | 925 |

| Angnao | 194 | ||

| Daqing | 193 | ||

| Gesai | 237 | ||

| Moyun | Bayang | 85 | 640 |

| Daying | 297 | ||

| Geyun | 145 | ||

| Jierao | 113 | ||

| Chadan | Baqing | 137 | 556 |

| Dagu | 95 | ||

| Qirong | 157 | ||

| Yueni | 167 | ||

| Angsai | Niandu | 318 | 762 |

| Reqing | 257 | ||

| Surao | 187 | ||

| Aduo | Jinai | 75 | 656 |

| Puke | 192 | ||

| Wahe | 247 | ||

| Duojia | 142 |

| Dimension Layer | Indicator Layer | Indicator Definition and Assignment | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buffer capacity | Health status (X1) | Subjective perception of the overall health status of family members. Unhealthy = 1, Not very healthy = 2, Average = 3, Fairly healthy = 4, Very healthy = 5 | 0.021 |

| Pasture area (X2) | Family-owned pasture area. None = 1, 1–500 mu = 2, 500–1000 mu = 3, Over 1000 mu = 4 | 0.030 | |

| Pasture quality (X3) | The condition of family pastures. Very poor = 1, Poor = 2, Average = 3, Fair = 4, Very good = 5 | 0.020 | |

| Livestock quantity (X4) | The number of cattle and sheep raised. None = 1, 1–50 heads = 2, 50–100 heads = 3, over 100 heads = 4 | 0.037 | |

| Per capita income (X5) | Total household income/Total household population (yuan) | 0.019 | |

| Household savings (X6) | The savings held by households. None = 1, 10,000–30,000 yuan = 2, 30,000–50,000 yuan = 3, 50,000–100,000 yuan = 4, Over 100,000 yuan = 5 | 0.046 | |

| Network of relatives and friends (X7) | The likelihood of receiving help from relatives and friends when facing difficulties. Very difficult = 1, Somewhat difficult = 2, Average = 3, Somewhat easy = 4, Very easy = 5 | 0.020 | |

| Cooperative participation (X8) | Whether to join the livestock cooperative. Yes = 1, No = 0 | 0.062 | |

| Housing capital (X9) | Whether owns property in the city. Yes = 1, No = 0 | 0.048 | |

| Motor vehicle (X10) | Whether the household owns a motor vehicle. Yes = 1, No = 0 | 0.04 | |

| Capacity for learning | Awareness of policies (X11) | Understand the status of ecological conservation policies. Completely unfamiliar = 1, Somewhat familiar = 2, Fairly familiar = 3, Quite familiar = 4, Very familiar = 5 | 0.021 |

| Skills training (X12) | Whether participated in skills training. Participated = 1, Did not participate = 0 | 0.062 | |

| Respondent’s education level (X13) | Below primary school = 1, primary school = 2, junior high school = 3, high school and vocational school = 4, college and above = 5 | 0.056 | |

| Information retrieval capability (X14) | Number of information access channels (units) | 0.046 | |

| Local resource utilization (X15) | Household Farming and Gathering Income/Total Household Income (%) | 0.016 | |

| Communicating with others (X16) | Frequency of interaction with other herding families. Never = 1, Occasionally = 2, Frequently = 3 | 0.023 | |

| Non-pastoral employment (X17) | Subjective perception of non-agricultural employment opportunities. No chance = 1, Very little = 2, Moderate = 3, Some = 4, Very good = 5 | 0.029 | |

| New skills and techniques (X18) | Willingness to learn new skills and techniques. Very unwilling = 1, Unwilling = 2, Neutral = 3, Willing = 4, Very willing = 5 | 0.014 | |

| Educational support (X19) | Parents’ willingness to support their children’s education Do not support = 1, Somewhat support = 2, Strongly support = 3 | 0.014 | |

| Proportion of family education expenditure (X20) | Household Education Expenditures/Total Household Expenditures (%) | 0.040 | |

| Self-organization | Climate change awareness (X21) | Understanding of climate change. Unfamiliar = 1, Somewhat familiar = 2, Fairly familiar = 3, Quite familiar = 4, Very familiar = 5 | 0.030 |

| Application of new technologies (X22) | Frequency of application of emerging technologies. Never = 1, Occasionally = 2, Frequently = 3 | 0.047 | |

| Livestock self-sufficiency (X23) | Self-sufficiency in livestock production. External purchases = 1, Purchases plus self-sufficiency = 2, Self-sufficient = 3 | 0.036 | |

| Grassland dependency (X24) | Highly dependent = 1, Moderately dependent = 2, Neutral = 3, Moderately independent = 4, Completely independent = 5 | 0.044 | |

| Participation in collective actions (X25) | Frequency of participation in community meetings. No participation = 1, Occasional participation = 2, Frequent participation = 3 | 0.031 | |

| Community rules (X26) | Compliance with community rules. Non-compliance = 1, Partial compliance = 2, Full compliance = 3 | 0.016 | |

| Cultural heritage (X27) | Participation in traditional cultural activities. Don’t participate = 1 Occasionally participate = 2 Frequently participate = 3 | 0.038 | |

| Livelihood diversity index (X28) | Number of livelihood types (species) | 0.025 | |

| Organizational involvement (X29) | Whether any family members hold positions in the community. Yes = 1, No = 0 | 0.043 | |

| Weak ties connectivity (X30) | Should one trust families with no blood ties. Distrust = 1, Partial trust = 2, Full trust = 3 | 0.026 |

| Grouping Variable | Grouping Categories | X8 (%) | X13 (%) | X12 (%) | X6 (%) | X14 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| whole sample | - | 8.14 | 7.58 | 7.18 | 6.40 | 5.97 |

| Gender | Male | 8.17 | 7.76 | 7.21 | 6.45 | 6.13 |

| Female | 8.04 | 6.98 | 7.18 | 6.22 | 5.74 | |

| Age | 18–35 | 8.24 | 5.99 | 6.77 | 6.51 | 6.21 |

| 35–60 | 8.11 | 8.64 | 7.37 | 6.62 | 5.97 | |

| Over 60 | 8.19 | 7.99 | 7.74 | 6.31 | 5.94 | |

| Functional partition | Core zone | 8.52 | 7.67 | 6.73 | 6.32 | 5.79 |

| General zone | 7.95 | 7.75 | 7.41 | 6.44 | 6.11 | |

| Livelihood type | Cordyceps-dependent | 8.26 | 7.43 | 7.21 | 6.22 | 5.76 |

| Livestock-dependent | 7.85 | 7.66 | 7.34 | 6.35 | 6.08 | |

| Diversified income | 8.15 | 7.78 | 7.27 | 6.59 | 6.13 | |

| Subsidy-dependent | 8.04 | 7.71 | 6.74 | 6.35 | 5.78 |

| Variables | Coef | Std. Err | z-Value | p-Value | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X6 | 0.016 | 0.012 | 1.296 | 0.195 | −0.008~0.039 |

| X8 | 0.085 | 0.011 | 7.492 | 0.000 ** | 0.063~0.108 |

| X12 | −0.020 | 0.017 | −1.131 | 0.258 | −0.053~0.014 |

| X13 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.807 | 0.420 | −0.009~0.022 |

| X14 | 0.036 | 0.006 | 6.102 | 0.000 ** | 0.024~0.048 |

| W × X6 | 0.026 | 0.033 | 0.792 | 0.428 | −0.039~0.091 |

| W × X8 | 0.147 | 0.034 | 4.328 | 0.000 ** | 0.080~0.214 |

| W × X12 | −0.029 | 0.057 | −0.507 | 0.612 | −0.141~0.083 |

| W × X13 | 0.014 | 0.018 | 0.794 | 0.427 | −0.021~0.048 |

| W × X14 | 0.010 | 0.021 | 0.483 | 0.629 | −0.031~0.051 |

| W × HLR | −0.787 | 0.242 | −3.245 | 0.001 ** | −1.262~−0.312 |

| Constant | 0.539 | 0.087 | 6.176 | 0.000 ** | 0.368~0.710 |

| Sample size | 19 | ||||

| R2 | 0.939 | ||||

| Adjust R2 | 0.843 | ||||

| F-value | F(6,12) = 9.569, p = 0.003 | ||||

| Variables | Effect | Effect Value | Std. Err | z-Value | p-Value | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X6 | ADI | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.957 | 0.339 | −0.013~0.039 |

| AII | 0.011 | 0.025 | 0.434 | 0.664 | −0.038~0.059 | |

| ATI | 0.023 | 0.023 | 1.018 | 0.309 | −0.022~0.068 | |

| X8 | ADI | 0.069 | 0.014 | 4.988 | 0.000 | 0.042~0.096 |

| AII | 0.061 | 0.022 | 2.798 | 0.005 | 0.018~0.103 | |

| ATI | 0.130 | 0.020 | 6.624 | 0.000 | 0.092~0.169 | |

| X12 | ADI | −0.017 | 0.024 | −0.686 | 0.493 | −0.065~0.031 |

| AII | −0.010 | 0.048 | −0.215 | 0.830 | −0.105~0.084 | |

| ATI | −0.027 | 0.036 | −0.757 | 0.449 | −0.097~0.043 | |

| X13 | ADI | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.584 | 0.559 | −0.011~0.020 |

| AII | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.546 | 0.585 | −0.018~0.031 | |

| ATI | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.894 | 0.371 | −0.014~0.036 | |

| X14 | ADI | 0.040 | 0.008 | 4.875 | 0.000 | 0.024~0.056 |

| AII | −0.014 | 0.015 | −0.916 | 0.360 | −0.043~0.016 | |

| ATI | 0.026 | 0.012 | 2.134 | 0.033 | 0.002~0.050 |

| Variable | Coefficient B | Std. Err | p-Value | ΔR2 | ΔF | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male × Participate in skills training | −0.013 ** | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.001 | 6.462 ** | −0.023~−0.003 |

| Male × college degree or above | −0.027 *** | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 4.193 *** | −0.043~−0.012 |

| Aged 35–60 × Participate in skills training | −0.007 * | 0.004 | 0.088 | 0.001 | 1.517 * | −0.016~0.001 |

| Aged 35–60 × primary school | 0.013 *** | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.002 | 1.821 ** | 0.004~0.048 |

| Aged over 60 × primary school | 0.026 ** | 0.011 | 0.019 | 0.003~0.023 | ||

| Core area × Savings of 5–10 million yuan | −0.019 * | 0.012 | 0.095 | 0.001 | 1.167 * | −0.042~0.003 |

| Core area × Join in cooperatives | −0.011 ** | 0.005 | 0.036 | 0.001 | 4.387 ** | −0.022~−0.001 |

| Subsidy-dependent × Participate in skills training | 0.017 * | 0.009 | 0.061 | 0.001 | 2.741 ** | −0.001~0.034 |

| Cordyceps-dependent × Information acquisition ability | 0.009 *** | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.002 | 5.104 *** | 0.002~0.015 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, J.; Song, Z.; Xu, B.; Dong, G.; Pan, T.; Ma, H. How Household Characteristics Drive Divergent Livelihood Resilience: A Case from the Lancang River Source Area of Sanjiangyuan National Park. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10755. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310755

Cao J, Song Z, Xu B, Dong G, Pan T, Ma H. How Household Characteristics Drive Divergent Livelihood Resilience: A Case from the Lancang River Source Area of Sanjiangyuan National Park. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10755. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310755

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Jiajun, Zhiyuan Song, Bin Xu, Gaoyang Dong, Ting Pan, and Hongbo Ma. 2025. "How Household Characteristics Drive Divergent Livelihood Resilience: A Case from the Lancang River Source Area of Sanjiangyuan National Park" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10755. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310755

APA StyleCao, J., Song, Z., Xu, B., Dong, G., Pan, T., & Ma, H. (2025). How Household Characteristics Drive Divergent Livelihood Resilience: A Case from the Lancang River Source Area of Sanjiangyuan National Park. Sustainability, 17(23), 10755. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310755