Can Virtual Influencers Drive Online Consumer Behavior? An Applied Examination of ELM Model Investigating the Marketing Effects of Virtual Influencers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Review and Hypothesis

2.1. From Real Influencers to Virtual Influencers: Evolution and Distinctions

2.2. Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM)

2.3. Source Credibility Theory

2.4. Perceived Product Values

2.5. Product Involvement

2.6. Conceptual Framework and Research Hyphotheses

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Sampling

3.2. The Measurement of the Constructs

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of Demographic Variables

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis of Research Variables

4.3. Common Method Bias of Research Variables

4.4. SEM Model Fit and Hypothesis Testing

4.5. Moderation Effect Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

5. Conclusions, Implications, Limitations, and Future Research

5.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- Based on dual-system theory, consumer decisions are guided by both intuitive and analytical processes. Low-involvement consumers may rely on intuitive judgments of value, whereas high-involvement consumers engage in deeper analysis—yet both ultimately depend on perceived value as the primary determinant of purchase intention, resulting in a non-significant moderating effect.

- (2)

- Product involvement itself may directly influence purchase decisions, leaving little variance for additional moderation [90]. Moreover, Zeithaml [48] argued that consumers universally rely on cognitive evaluations of value—such as price-performance ratio and perceived quality—when making purchase decisions, a mechanism that operates largely independent of involvement level. When perceived value is sufficiently high, both high- and low-involvement consumers perceive the product as “worth buying”.

- (3)

- Product category differences may also explain this finding. The products featured in the experimental stimuli (furniture and handbags) are utilitarian in nature, for which cognitive value tends to be the dominant determinant of purchase behavior, while involvement plays a secondary role [91]. Even highly involved consumers, after extensive consideration, are ultimately guided by perceived value in their purchase decisions.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kanaveedu, A.; Kalapurackal, J.J. Influencer marketing and consumer behaviour: A systematic literature review. Vis. J. Bus. Perspect. 2024, 28, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbaere, M.; Michael, B.; Phillips, B.J. Social media influencers: A route to brand engagement for their followers. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 38, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, C.W.; Cuevas, L.M.; Chong, S.M.; Lim, H. Influencer marketing: Social media influencers as human brands attaching to followers and yielding positive marketing results by fulfilling needs. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.V.; Ryu, E. I’ll buy what she’s wearing: The roles of envy toward and parasocial interaction with influencers in Instagram celebrity-based brand endorsement and social commerce. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K.; Perez, C. You follow fitness influencers on YouTube. But do you actually exercise? How parasocial relationships, and watching fitness influencers, relate to intentions to exercise. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, Y.A.; Wang, Z.; Kim, Y.; Yin, Z. The effects of visual congruence on brand communication effectiveness in social media. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 111, 170–182. [Google Scholar]

- Tafesse, W.; Wood, B.P. Followers’ engagement with Instagram influencers: The role of influencers’ content and engagement strategy. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafarova, E.; Trofimenko, O. ‘Instafamous’—Credibility and self-presentation of micro-celebrities on social media. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2018, 22, 1432–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.L.; Fowler, K. Close encounters of the AI kind: Use of AI influencers as brand endorsers. J. Advert. 2021, 50, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhawar, R.; Kumar, R.; Varshney, S. Impact of social media influencers on consumer buying behavior. Vis. J. Bus. Perspect. 2023, 27, 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kádeková, Z.; Holienčinová, M. Influencer marketing as a modern phenomenon creating a new frontier of virtual opportunities. Commun. Today 2018, 9, 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, F.; Fu, L.; Jiang, Q. Virtual idols vs online influencers vs traditional celebrities: How young consumers respond to their endorsement advertising. Young Consum. 2023, 25, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Schumann, D. Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement. J. Consum. Res. 1983, 10, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 19, 123–205. [Google Scholar]

- Farivar, S.; Wang, F.; Yuan, Y. Influencer marketing: A perspective of the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 24, 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.Y.; Kim, H.Y. Trust me, trust me not: A nuanced view of influencer marketing on social media. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Lee, Y. The effect of social media influencer characteristics on consumer trust and brand attitude. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021, 33, 698–715. [Google Scholar]

- Hovland, C.I.; Janis, I.L.; Kelley, H.H. Communication and Persuasion; Yale Univ Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Croes, E.A.; Antheunis, M.L.; Schouten, A.P.; Krahmer, E.J. Social attraction in video-mediated communication: The role of nonverbal affiliative behavior. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2019, 36, 1210–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzoumaka, E.; Tsiotsou, R.H.; Siomkos, G.J. Delineating the role of endorser’s perceived qualities and consumer characteristics on celebrity endorsement effectiveness. J. Mark. Commun. 2016, 22, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhawar, A.; Kumar, P.; Varshney, S. The emergence of virtual influencers: A shift in the influencer marketing paradigm. Young Consum. 2023, 24, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Ali, A.A.; Ali, A.A.; Mostapha, N. The role of country of origin, perceived value, trust, and influencer marketing in determining purchase intention in social commerce. BAU J. Soc. Cult. Hum. Behav. 2021, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifah, B.; Ramdan, A.M.; Jhoansyah, D. Analysis of social media influencers on purchase intention through perceived value as a mediating variable. Dinasti Int. J. Econ. Financ. Account. 2024, 5, 2364–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, R.B. Customer value: The next source for competitive advantage. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1997, 25, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.; Callarisa, L.; Rodriguez, R.M.; Moliner, M.A. Perceived value of the purchase of a tourism product. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Emmert, J. Measuring product category involvement: A multitrait–multimethod study. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 23, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.; Prashar, S.; Parsad, C.; Vijay, T.S. Mediating role of consumer involvement between celebrity endorsement and consumer evaluation: Comparative study of high and low involvement product. Asian Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 24, 113–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halin, J. The Effect of Influencer Marketing in a Highly Involved Product: An Experiment Conducted in the Golf Industry. Master’s Thesis, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Munnukka, J.; Uusitalo, O.; Toivonen, H. Credibility of a peer endorser and advertising effectiveness. J. Consum. Mark. 2016, 33, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.H.; Yeh, Y.J. Marketing effectiveness on travel blogs: The perspective from elaboration likelihood model. Sun Yat-Sen. Manag. Rev. 2011, 19, 517–555. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, R. How advertising works: A planning model. J. Advert. Res. 1980, 20, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlich, M. Perceptions and acceptance of artificial intelligence: A multi-dimensional study. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Pandey, N.; Currie, W.; Micu, A. Leveraging ChatGPT and other generative artificial intelligence (AI)-based applications in the hospitality and tourism industry: Practices, challenges and research agenda. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Attitudes and Persuasion: Classic and Contemporary Approaches; William C. Brown: Dubuque, IA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.M.K.; Sia, C.L.; Kuan, K.K.Y. Is this review believable? A study of factors affecting the credibility of online consumer reviews from an ELM perspective. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Yang, P.; Gao, Y.; Tan, Y.; Yang, C. The effects of ad social and personal relevance on consumer ad engagement on social media: The moderating role of platform trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 122, 106834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchen, P.J.; Kerr, G.; Schultz, D.E.; McColl, R.; Pals, H. The elaboration likelihood model: Review, critique and research agenda. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 2033–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.; Weiss, W. The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opin. Q. 1951, 15, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, R. The impact of celebrity spokespersons’ perceived image on consumers’ intention to purchase. J. Advert. Res. 1991, 31, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.W.; Scheinbaum, A.C. Enhancing brand credibility via celebrity endorsement: Trustworthiness trumps attractiveness and expertise. J. Advert. Res. 2018, 58, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phua, J.; Jin, S.V.; Hahm, J.M. Celebrity-endorsed e-cigarette brand Instagram advertisements: Effects on young adults’ attitudes toward e-cigarettes and smoking intentions. J. Health Commun. 2018, 23, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colliander, J.; Marder, B. Snap happy brands: Increasing publicity effectiveness through a snapshot aesthetic when marketing a brand on Instagram. Comput. Human. Behav. 2018, 78, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K.; Kefi, H. Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-H. Does a Good Endorser Need to be Perfect? The Influence of Actual–Ideal Self-Congruence on Endorsement Effectiveness and Followership: The Mediating Roles of Credibility, Expertise, and Attractiveness. Master’s Thesis, National Taipei University, New Taipei, Taiwan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.; Shiu, E.; Hassan, L.M. Replicating, validating, and reducing the length of the consumer perceived value scale. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zauner, A.; Koller, M.; Hatak, I. Customer perceived value—Conceptualization and avenues for future research. Cogent Psychol. 2015, 2, 1061782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawitri, S.; Hasin, A. Online music business: The relationship between perceived benefit, perceived sacrifice, perceived value, and purchase intention. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Bao, Y.; Sheng, S. Motivating purchase of private brands: Effects of store image, product signatureness, and quality variation. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehzadeh, R.; Pool, J.K. Brand attitude and perceived value and purchase intention toward global luxury brands. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2016, 29, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, T.P.; Hoffman, D.L.; Yung, Y.F. Measuring the customer experience in online environments: A structural modeling approach. Mark. Sci. 2000, 19, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, B.; Jafari, A.; O’Gorman, K. Keeping your audience: Presenting a visitor engagement scale. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Young, S.M. Consumer response to television commercials: The impact of involvement and background music on brand attitude formation. J. Mark. Res. 1986, 23, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Chaudhry, S.S. Enhancing consumer engagement in e-commerce live streaming via relational bonds. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 1019–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Sokol, D. How incumbents respond to competition from innovative disruptors in the sharing economy—The impact of Airbnb on hotel performance. Strat. Mgmt J. 2022, 43, 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidmon, S. How does attachment style influence the brand attachment–brand trust and brand loyalty chain in adolescents? Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 854–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L. Cross-border e-commerce platform for commodity automatic pricing model based on deep learning. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Till, B.D.; Busler, M. Matching products with endorsers: Attractiveness versus expertise. J. Consum. Mark. 1998, 15, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Sung, Y. The roles of spokesperson and endorser credibility in consumer evaluation of advertising. J. Advert. 2010, 39, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Méndez, J.I.; Papadopoulos, N.; Alwan, M. Testing self-congruity theory in the context of nation brand personality. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 2015, 24, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.L.; Johnson, J.W. The impact of celebrity expertise on advertising effectiveness: The mediating role of trust. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 168–188. [Google Scholar]

- Schouten, A.P.; Janssen, L.; Verspaget, M. Celebrity vs. influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and product-endorser fit. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Watkins, B. YouTube vloggers’ influence on consumer luxury brand perceptions and intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5753–5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafarova, E.; Rushworth, C. Exploring the credibility of online celebrities’ Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Comput. Human. Behav. 2017, 68, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K. Consumer behavior and brand attachment in the digital age. J. Bus. Retail. Manag. Res. 2018, 13, 188–198. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, X.; Moutinho, L. The role of brand image, product involvement, and knowledge in explaining consumer purchase behaviour of counterfeits. Eur. J. Mark. 2011, 45, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drossos, D.; Giaglis, G.M.; Lekakos, G.; Kokkinaki, F.; Stavraki, M.G. Determinants of effective SMS advertising: A cross-cultural study. J. Interact. Advert. 2007, 7, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H. The Effects of Involvement, Price Acceptance, and Perceived Value on Purchase Intention of Organic Food. Master’s Thesis, National Chung Hsing University, New Taipei, Taiwan, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, R.D.; Miniard, P.W.; Engel, J.F. Consumer Behavior; Harcourt College Publishers: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes, J. Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used? An experiment using 5-point, 7-point and 10-point scales. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 50, 61–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D. Likert scale: Explored and explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, C.C.; Colman, A.M. Optimal number of response categories in rating scales: Reliability, validity, discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta Psychol. 2000, 104, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grewal, D.; Monroe, K.B.; Krishnan, R. The effects of price-comparison advertising on buyers’ perceptions of acquisition value, transaction value, and behavioral intentions. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teas, R.K.; Agarwal, S. The effects of extrinsic product cues on consumers’ perceptions of quality, sacrifice, and value. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton Univ Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Hong, S. Power analysis in covariance structure modeling using GFI and AGFI. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1997, 32, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafarova, E.; Bowes, T. ‘Instagram made me buy it’: Generation Z impulse purchases in the fashion industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P.; Ho, M.R. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analysis. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokzadeh, G.; Koufteros, X.; Pflughoeft, K. Confirmatory analysis of computer self-efficacy. Struct. Equ. Model. 2003, 10, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaski, J.F.; Nevin, J.R. The differential effects of exercised and unexercised power sources in a marketing channel. J. Mark. Res. 1985, 22, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Saraf, N.; Hu, Q.; Xue, Y. Assimilation of enterprise systems: The effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.M.; Wang, E.T.; Fang, Y.H.; Huang, H.Y. Understanding customers’ repeat purchase intentions in B2C e-commerce: The roles of utilitarian value, hedonic value and perceived risk. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, W.J. Attitudes and attitude change. In Handbook of Social Psychology, 3rd ed.; Lindzey, G., Aronson, E., Eds.; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1985; Volume 2, pp. 233–346. [Google Scholar]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the involvement construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, B. Measuring purchase-decision involvement. Psychol. Mark. 1989, 6, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, B.J.; Phillips, L.W.; Tybout, A.M. Designing research for application. J. Consum. Res. 1981, 8, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A.; Merunka, D.R. Convenience samples of college students and research reproducibility. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.; Kaye, S.A.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. What factors contribute to the acceptance of artificial intelligence? A systematic review. Telemat. Inform. 2023, 77, 101925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Item | Frequency | Percentage | Dimension | Item | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 130 | 37.8% | Education Level | University | 248 | 72.1% |

| Female | 214 | 62.2% | Graduate school or above | 34 | 9.9% | ||

| Age | 20 or below | 96 | 27.9% | Average Monthly Income | ≤30,000 TWD | 244 | 70.9% |

| 21~30 | 184 | 53.5% | 30,001–50,000 TWD | 44 | 12.8% | ||

| 31~40 | 10 | 2.9% | 50,001–70,000 TWD | 26 | 7.6% | ||

| 41~50 | 30 | 8.7% | ≥70,000 TWD | 30 | 8.7% | ||

| 51 or above | 24 | 7.0% | Weekly Interaction with AI Virtual Influencers | 1 time | 286 | 83.1% | |

| Education Level | Junior high school or below | 14 | 4.1% | 2–3 times | 38 | 11.0% | |

| High school/vocational school | 48 | 14.0% | ≥4 times | 20 | 5.8% |

| Construct | Item | Unstandardized Loading | C.R. (t-Value) | p-Value | Standardized Loading | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Product Value | PV1 | 1.000 | 0.707 | 0.820 | 0.605 | ||

| PV2 | 1.356 | 9.070 | *** | 0.813 | |||

| PV3 | 1.328 | 9.039 | *** | 0.808 | |||

| Trustworthiness | TR1 | 1.000 | 0.845 | 0.913 | 0.723 | ||

| TR2 | 0.949 | 14.379 | *** | 0.871 | |||

| TR3 | 0.994 | 14.702 | *** | 0.883 | |||

| TR4 | 0.865 | 12.574 | *** | 0.800 | |||

| Expertise | EXP1 | 1.000 | 0.852 | 0.852 | 0.658 | ||

| EXP2 | 0.944 | 11.312 | *** | 0.789 | |||

| EXP3 | 0.956 | 11.334 | *** | 0.791 | |||

| Attractiveness | ATC1 | 1.000 | 0.914 | 0.919 | 0.792 | ||

| ATC2 | 1.097 | 18.617 | *** | 0.954 | |||

| ATC3 | 0.976 | 12.936 | *** | 0.793 | |||

| Product Involvement | PI1 | 1.000 | 0.750 | 0.869 | 0.624 | ||

| PI2 | 0.996 | 10.238 | *** | 0.800 | |||

| PI3 | 1.082 | 10.665 | *** | 0.835 | |||

| PI4 | 0.984 | 9.866 | *** | 0.772 | |||

| Purchase Intentions | INT1 | 1.000 | 0.905 | 0.895 | 0.739 | ||

| INT2 | 0.914 | 15.368 | *** | 0.849 | |||

| INT3 | 0.855 | 14.491 | *** | 0.823 | |||

| Model Fit: χ2/df = 1.509, GFI = 0.881, AGFI = 0.838, RMSEA = 0.055, CFI = 0.966 | |||||||

| Perceived Product Value | Trustworthiness | Expertise | Attractiveness | Product Involvement | Purchase Intentions | |

| Perceived Product Value | 0.605 | |||||

| Trustworthiness | 0.463 *** | 0.723 | ||||

| Expertise | 0.350 *** | 0.607 *** | 0.658 | |||

| Attractiveness | 0.484 *** | 0.532 *** | 0.393 *** | 0.792 | ||

| Product Involvement | 0.394 *** | 0.378 *** | 0.363 *** | 0.466 *** | 0.624 | |

| Purchase Intentions | 0.541 *** | 0.662 *** | 0.598 *** | 0.639 *** | 0.621 *** | 0.739 |

| Construct | Indicator | Substantive Factor Loading (R1) | R12 | Method Factor Loading (R2) | R22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Product Value | PV1 | 0.707 *** | 0.499 | 0.142 | 0.02 |

| PV2 | 0.813 *** | 0.661 | 0.111 | 0.012 | |

| PV3 | 0.808 *** | 0.653 | −0.139 | 0.019 | |

| Trustworthiness | TR1 | 0.845 *** | 0.714 | 0.093 | 0.009 |

| TR2 | 0.871 *** | 0.759 | 0.083 | 0.007 | |

| TR3 | 0.883 *** | 0.78 | 0.184 | 0.034 | |

| TR4 | 0.800 *** | 0.64 | 0.199 + | 0.039 | |

| Expertise | EXP1 | 0.852 *** | 0.726 | 0.128 | 0.016 |

| EXP2 | 0.789 *** | 0.623 | −0.177 | 0.031 | |

| EXP3 | 0.791 *** | 0.626 | 0.189 | 0.036 | |

| Attractiveness | ATC1 | 0.914 *** | 0.835 | 0.049 | 0.002 |

| ATC2 | 0.954 *** | 0.91 | 0.021 | 0.001 | |

| ATC3 | 0.793 *** | 0.629 | 0.183 | 0.033 | |

| Product Involvement | PI1 | 0.750 *** | 0.563 | 0.271 * | 0.073 |

| PI2 | 0.800 *** | 0.641 | 0.164 | 0.027 | |

| PI3 | 0.835 *** | 0.697 | 0.185 | 0.034 | |

| PI4 | 0.772 *** | 0.596 | −0.238 * | 0.057 | |

| Purchase Intentions | INT1 | 0.905 *** | 0.819 | 0.046 | 0.002 |

| INT2 | 0.849 *** | 0.721 | 0.109 | 0.012 | |

| INT3 | 0.823 *** | 0.677 | 0.136 | 0.018 | |

| Average | 0.828 | 0.688 | 0.087 | 0.024 |

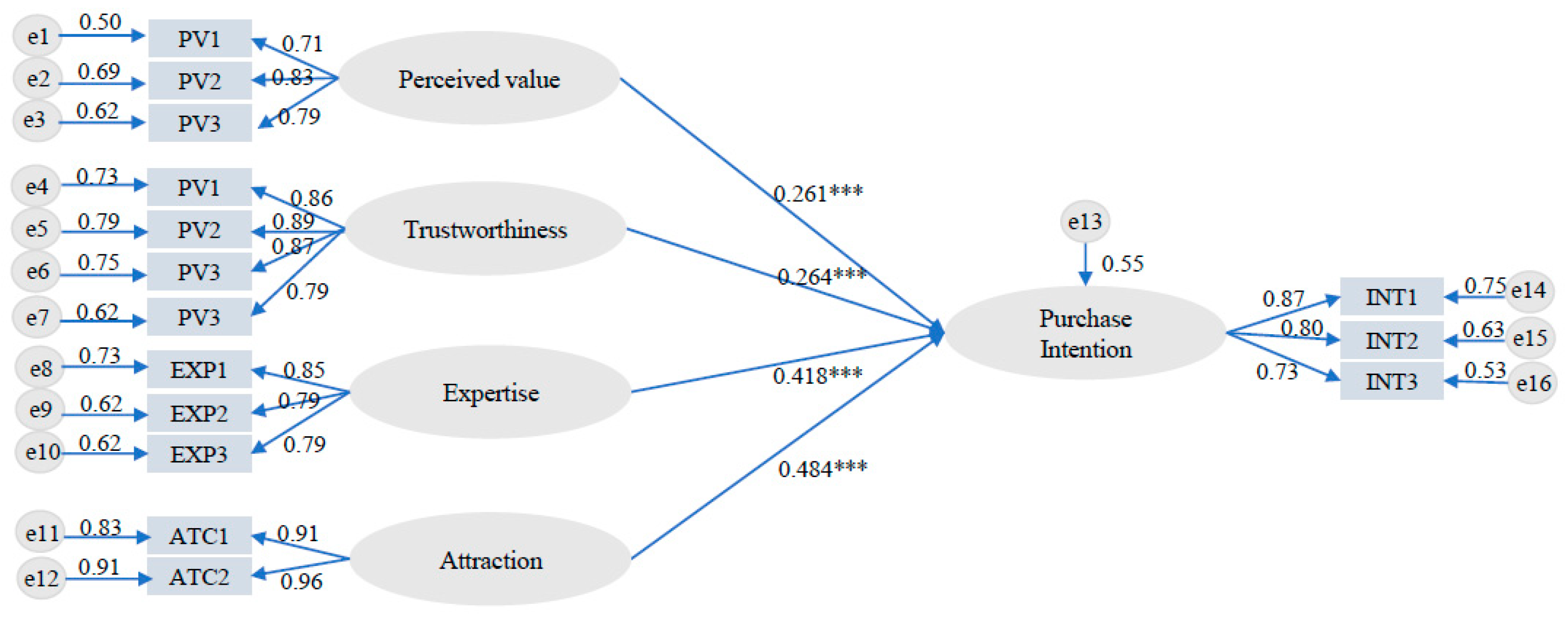

| Relationship | Unstandardized Estimate | Standardized Estimate | C.R. (t-Value) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase Intentions ← Perceived Product Value | 0.361 | 0.261 | 3.568 | *** |

| Purchase Intentions ← Virtual Influencer Trustworthiness | 0.242 | 0.264 | 3.913 | *** |

| Purchase Intentions ← Virtual Influencer Expertise | 0.375 | 0.418 | 5.711 | *** |

| Purchase Intentions ← Virtual Influencer Attractiveness | 0.366 | 0.484 | 6.929 | *** |

| Independent Variable | Model | Description | χ2 | Degrees of Freedom | Δχ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Product Value | Model 1 | Baseline Model | 53.562 | 32 | |

| Model 2 | Moderated Model | 53.682 | 33 | 0.12 | |

| Trustworthiness | Model 3 | Baseline Model | 113.126 | 52 | |

| Model 4 | Moderated Model | 115.992 | 53 | 2.866 * | |

| Expertise | Model 5 | Baseline Model | 39.608 | 32 | |

| Model 6 | Moderated Model | 40.596 | 33 | 0.988 | |

| Attractiveness | Model 7 | Baseline Model | 60.992 | 32 | |

| Model 8 | Moderated Model | 73.029 | 33 | 11.037 * |

| Moderator | Path | Low Involvement Group | High Involvement Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product Involvement | Purchase Intentions ← Perceived Product Value | 0.525 | 0.621 |

| Purchase Intentions ← Virtual Influencer Trustworthiness | 0.549 *** | 0.866 *** | |

| Purchase Intentions ← Virtual Influencer Expertise | 0.586 | 0.716 | |

| Purchase Intentions ← Virtual Influencer Attractiveness | 0.515 *** | 0.750 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tseng, W.-K.; Ou, C.-C. Can Virtual Influencers Drive Online Consumer Behavior? An Applied Examination of ELM Model Investigating the Marketing Effects of Virtual Influencers. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310721

Tseng W-K, Ou C-C. Can Virtual Influencers Drive Online Consumer Behavior? An Applied Examination of ELM Model Investigating the Marketing Effects of Virtual Influencers. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310721

Chicago/Turabian StyleTseng, Wei-Kuo, and Chueh-Chu Ou. 2025. "Can Virtual Influencers Drive Online Consumer Behavior? An Applied Examination of ELM Model Investigating the Marketing Effects of Virtual Influencers" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310721

APA StyleTseng, W.-K., & Ou, C.-C. (2025). Can Virtual Influencers Drive Online Consumer Behavior? An Applied Examination of ELM Model Investigating the Marketing Effects of Virtual Influencers. Sustainability, 17(23), 10721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310721