The Role of Experienced Employees’ Calling Orientation in Shaping Responses to Newcomers’ Approach- and Avoidance-Oriented Job Crafting: A Vignette-Based Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Conservation of Resources Theory

2.2. Job Crafting

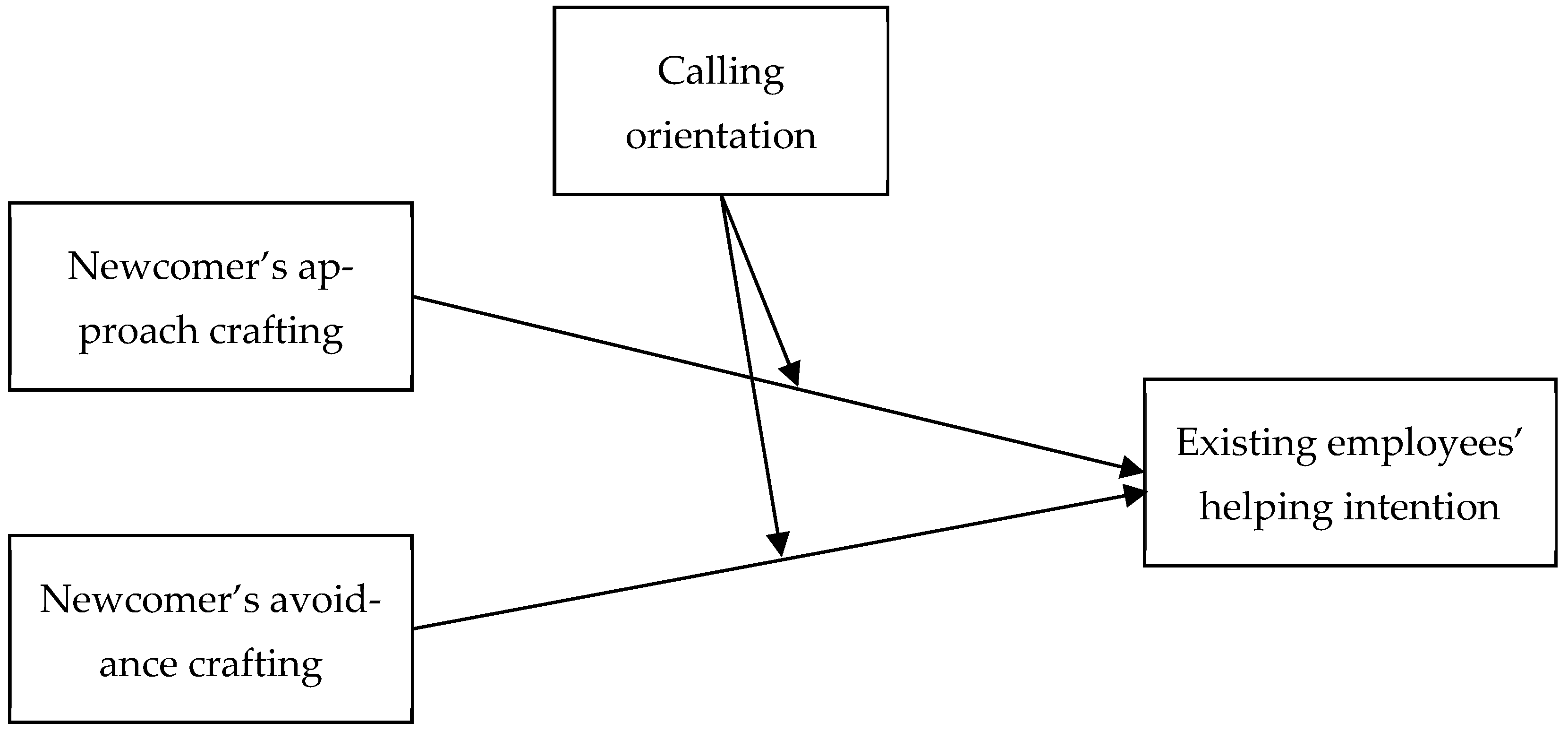

2.3. Newcomers’ Job Crafting and Existing Workers’ Helping Intention

2.4. Calling Orientation

2.5. Interaction of Job Crafting and Calling Orientation

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

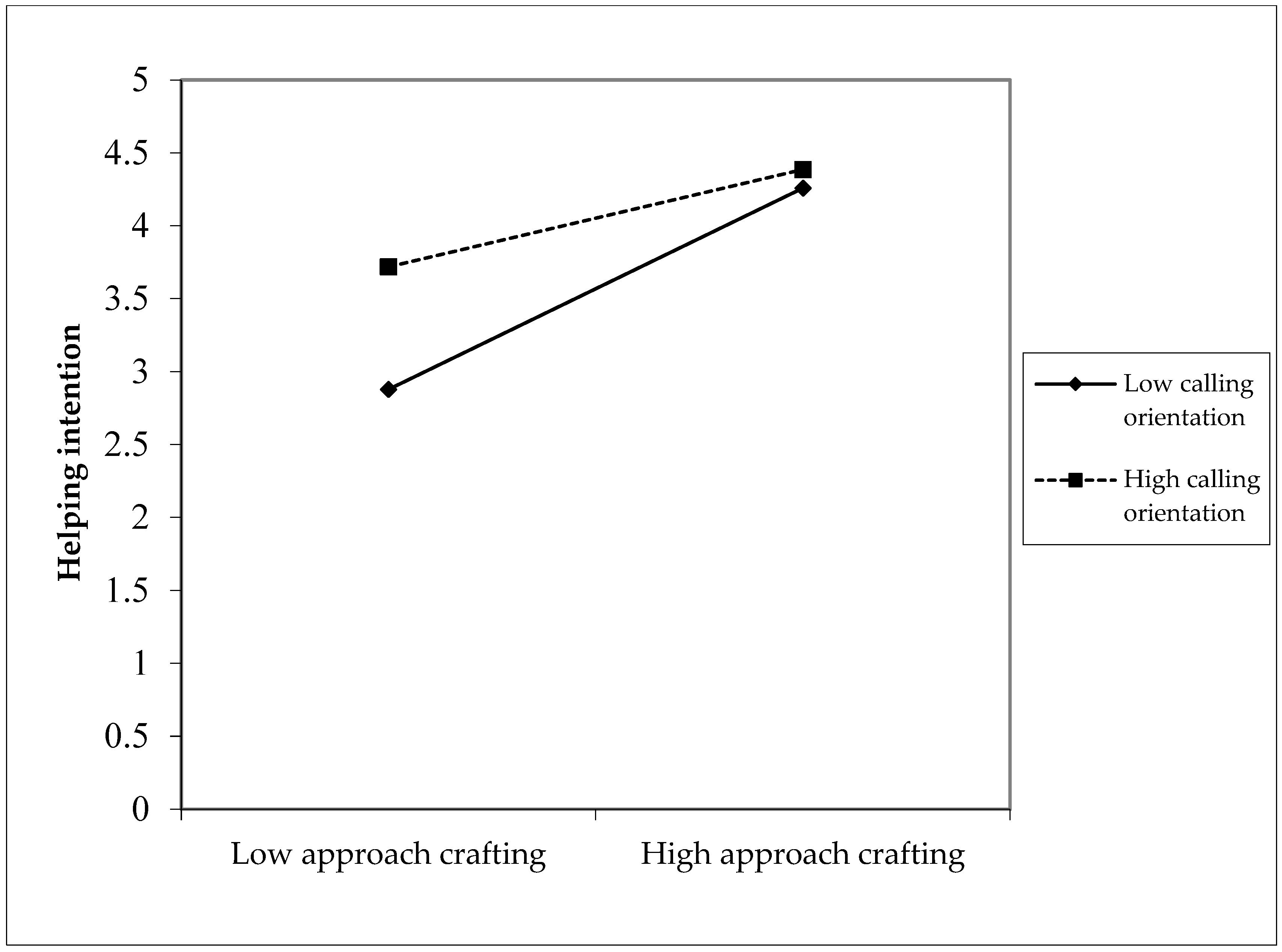

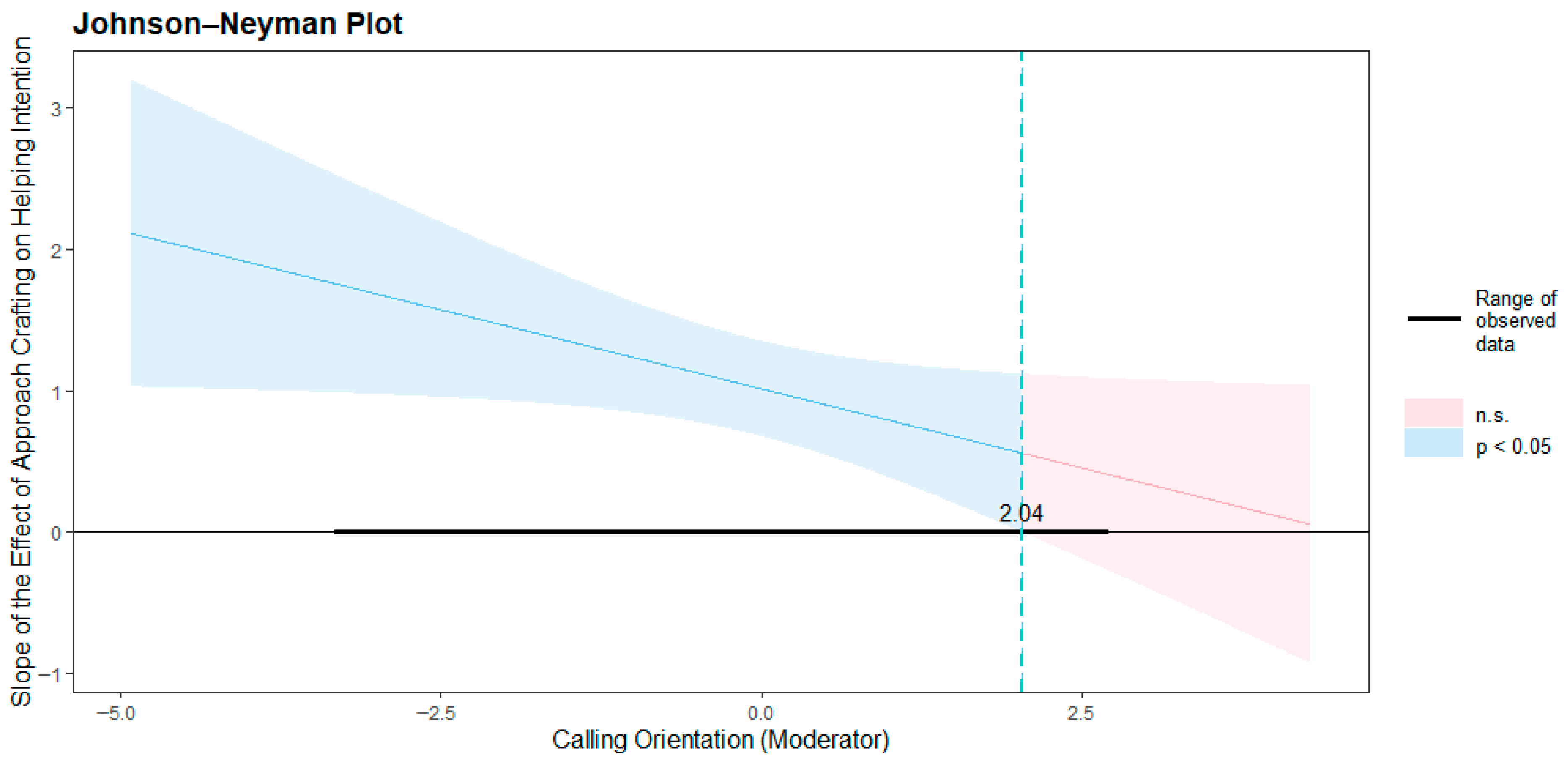

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B. Scale Items Used in the Study

- I enjoy talking about my future work with others.

- I view my future work as my life’s mission.

- My work will be one of the most important things in my life.

- My work will make the world a better place.

- My work will give my life meaning.

- Chris makes sure that his/her work is mentally less intense.

- Chris tries to ensure that his/her work is emotionally less intense.

- Chris manages his/her work so that he/she tries to minimize contact with people whose problems affect him/her emotionally.

- Chris organizes his/her work so as to minimize contact with people whose expectations are unrealistic.

- Chris tries to ensure that he/she does not have to make many difficult decisions at work.

- Chris organizes his/her work in such a way to make sure that he/she does not have to concentrate for too long a period at once.

- Chris has asked others for feedback on his/her job performance.

- Chris has asked colleagues for advice.

- Chris has asked his/her supervisor for advice.

- Chris has tried to learn new things at work.

- Chris has asked for more tasks if he/she finishes his/her work.

- Chris has asked for more responsibilities.

- Chris has asked for more odd jobs.

- I am willing to volunteer to do things to help out Chris.

- I am willing to work cooperatively with Chris.

- I am willing to spend time helping Chris with his/her work tasks because I want to.

Appendix C. Robustness Checks

References

- Work Institute. 2025 Retention Report: Employee Retention Truths in Today’s Workplace; Work Institute: Franklin, TN, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, S.; Li, H. Occupational self-efficacy, job crafting and job satisfaction in newcomer socialization: A moderated mediation model. J. Manag. Psychol. 2023, 38, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Wang, H.; Long, L. Will newcomer job crafting bring positive outcomes? The role of leader–member exchange and traditionality. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2020, 52, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, S.; Zhou, J. The impact of challenge and hindrance stressors on newcomers’ organizational socialization: A moderated-mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 968852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellah, R.N.; Madsen, R.; Sullivan, W.M.; Swidler, A.; Tipton, S.M. Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; McCauley, C.; Rozin, P.; Schwartz, B. Jobs, careers, and callings: People’s relations to their work. J. Res. Personal. 1997, 31, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Parker, S.K. Reorienting job crafting research: A hierarchical structure of job crafting concepts and integrative review. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Neveu, J.-P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. S. Afr. J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazazzara, A.; Tims, M.; De Gennaro, D. The process of reinventing a job: A meta-synthesis of qualitative job crafting research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 116, 103267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, P.W.; Fischbach, A. A meta-analysis on promotion- and prevention-focused job crafting. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Katz, I.M.; Lavigne, K.N.; Zacher, H. Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 102, 112–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.N.; Erdogan, B. Organizational socialization: The effective onboarding of new employees. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Zedeck, S., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Volume 3, pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, T.B.; Li, N.; Boswell, W.R.; Zhang, X.A.; Xie, Z. Getting what’s new from newcomers: Empowering leadership, creativity, and adjustment in the socialization context. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 67, 567–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Twemlow, M.; Fong, C.Y.M. A state-of-the-art overview of job-crafting research: Current trends and future research directions. Career Dev. Int. 2022, 27, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.Y.M.; Tims, M.; Khapova, S.N.; Beijer, S. Supervisor reactions to avoidance job crafting: The role of political skill and approach job crafting. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 70, 1209–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.Y.M.; Tims, M.; Khapova, S.N. Coworker responses to job crafting: Implications for willingness to cooperate and conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 2022, 138, 103781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.J.; Jiang, J. Why is crafting the job associated with less prosocial reactions and more social undermining? The role of feelings of relative deprivation and zero-sum mindset. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 184, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Zhao, X.; Hu, B.; Li, Z.; Xia, J. Challenge or threat? Examining when and how employees react positively and negatively to coworkers’ job crafting. J. Bus. Psychol. 2024, 39, 1413–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Parker, S.K. How coworkers attribute, react to, and shape job crafting. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 10, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Klotz, A.C.; Turnley, W.H.; Harvey, J. Exploring the dark side of organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 542–559. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, S.M.; Van Dyne, L.; Kamdar, D. The contextualized self: How team–member exchange leads to coworker identification and helping OCB. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.S.; Forret, M. Exchange relationships at work: An examination of the relationship between team-member exchange and supervisor reports of organizational citizenship behavior. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2008, 14, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, J.R.; Brown, D.J.; Keeping, L.M.; Lian, H. Helpful today, but not tomorrow? Feeling grateful as a predictor of daily organizational citizenship behaviors. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 67, 705–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-Thomas, H.D.; Burke, S.E. Newcomer proactive behavior: Can there be too much of a good thing? In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Socialization; Wanberg, C.R., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 56–77. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, J.M.; Grant, A.M.; Johnson, V. When callings are calling: Crafting work and leisure in pursuit of unanswered occupational callings. Organ. Sci. 2010, 21, 973–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D. Calling and vocation at work: Definitions and prospects for research and practice. Couns. Psychol. 2009, 37, 424–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrow Riza, S.D.; Heller, D. Follow your heart or your head? A longitudinal study of the facilitating role of calling and ability in the pursuit of a challenging career. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elangovan, A.R.; Pinder, C.C.; McLean, M. Callings and organizational behavior. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D. Measuring meaningful work: The Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI). J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea-Van Fossen, R.; Vredenburgh, D.J. Exploring differences in work’s meaning: An investigation of individual attributes associated with work orientations. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 2014, 15, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunderson, J.S.; Thompson, J.A. The call of the wild: Zookeepers, callings, and the double-edged sword of deeply meaningful work. Adm. Sci. Q. 2009, 54, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Zhou, W.; Huang, J.L.; Xia, M. Using goal facilitation theory to explain the relationships between calling and organization-directed citizenship behavior and job satisfaction. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 100, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2011, 18, 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, D.J.; Moss, A.J.; Rosenzweig, C.; Jaffe, S.N.; Robinson, J.; Litman, L. Evaluating CloudResearch’s Approved Group as a solution for problematic data quality on MTurk. Behav. Res. Methods 2023, 55, 3953–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, B.D.; Ewell, P.J.; Brauer, M. Data quality in online human-subjects research: Comparisons between MTurk, Prolific, CloudResearch, Qualtrics, and SONA. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, D.G. Do organizational socialization tactics influence newcomer embeddedness and turnover. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.N.; Green, S.G. Effect of newcomer involvement in work-related activities: A longitudinal study of socialization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, A.A.; Dunn, A.M.; Shanock, L.R.; Sargent, A.C.; Kavanagh, K.A.; Leonard, S. You being new can be hard on me too: Considering the veteran employee during newcomer socialization. Hum. Perform. 2022, 35, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, T.; Lipshits-Braziler, Y.; Gati, I. Construction and initial validation of the Work Orientation Questionnaire. J. Career Assess. 2020, 28, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Hetland, J. Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 1120–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glomb, T.M.; Bhave, D.P.; Miner, A.G.; Wall, M. Doing good, feeling good: Examining the role of organizational citizenship behaviors in changing mood. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 191–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.W. Role definitions and organizational citizenship behavior: The importance of the employee’s perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 1543–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Curran, P.J.; Bauer, D.J. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2006, 31, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, G.; Okechuku, C.; Zhang, H.; Cao, J. Impact of job satisfaction and personal values on the work orientation of Chinese accounting practitioners. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newness, K.A. Exploring Calling Work Orientation: Construct Clarity and Organizational Implications. Ph.D. Thesis, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA, 2013. Available online: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/980 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Kolodinsky, R.W.; Ritchie, W.J.; Kuna, W.A. Meaningful engagement: Impacts of a ‘calling’ work orientation and perceived leadership support. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 24, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Su, R.; Ptashnik, T.; Nielsen, J. Feeling good, doing good, and getting ahead: A meta-analytic investigation of the outcomes of prosocial motivation at work. Psychol. Bull. 2022, 148, 158–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrow, S.R.; Tosti-Kharas, J. Calling: The development of a scale measure. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 1001–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Approach manipulation condition a | 75 | - | - | - | |||

| 2. Avoidance manipulation condition a | 74 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 3. Calling orientation b | 149 | 4.35 | 1.59 | 0.09 | 0.19 | (0.91) | |

| 4. Helping intention c | 149 | 3.69 | 1.02 | −0.47 *** | 0.59 *** | 0.21 * | (0.91) |

| Helping Intention | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | B | β | SE | t | B 95% CI [LB, UB] | p |

| Model 1 | ||||||

| Intercept | 3.22 | 0.13 | 25.51 | [2.97, 3.47] | <0.001 | |

| Approach crafting condition | 1.12 | 0.59 | 0.18 | 6.31 | [0.76, 1.47] | <0.001 |

| R2 | 0.35 | |||||

| ∆R2 | - | |||||

| Model 2 | ||||||

| Intercept | 3.27 | 0.12 | 26.77 | [3.03, 3.52] | <0.001 | |

| Approach crafting condition | 1.02 | 0.55 | 0.17 | 5.93 | [0.68, 1.37] | <0.001 |

| Calling orientation | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 2.79 | [0.04, 0.26] | 0.007 |

| R2 | 0.42 | |||||

| ∆R2 | 0.06 | |||||

| Model 3 | ||||||

| Intercept | 3.31 | 0.12 | 27.38 | [3.07, 3.55] | <0.001 | |

| Approach crafting condition | 1.01 | 0.54 | 0.17 | 6.00 | [0.68, 1.35] | <0.001 |

| Calling orientation | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.08 | 3.50 | [0.11, 0.41] | <0.001 |

| Approach × Calling orientation | −0.22 | −0.26 | 0.11 | −2.10 | [−0.44, −0.01] | 0.040 |

| R2 | 0.45 | |||||

| ∆R2 | 0.03 | |||||

| Helping Intention | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | B | β | SE | t | B 95% CI [LB, UB] | p |

| Model 1 | ||||||

| Intercept | 4.11 | 0.16 | 25.82 | [3.79, 4.43] | <0.001 | |

| Avoidance crafting condition | −1.03 | −0.47 | 0.23 | −4.56 | [−1.48, −0.58] | <0.001 |

| R2 | 0.22 | |||||

| ∆R2 | - | |||||

| Model 2 | ||||||

| Intercept | 4.11 | 0.16 | 25.93 | [3.79, 4.43] | <0.001 | |

| Avoidance crafting condition | −1.05 | −0.49 | 0.23 | −4.68 | [−1.50, −0.60] | <0.001 |

| Calling orientation | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 1.25 | [−0.05, 0.23] | 0.217 |

| R2 | 0.24 | |||||

| ∆R2 | 0.02 | |||||

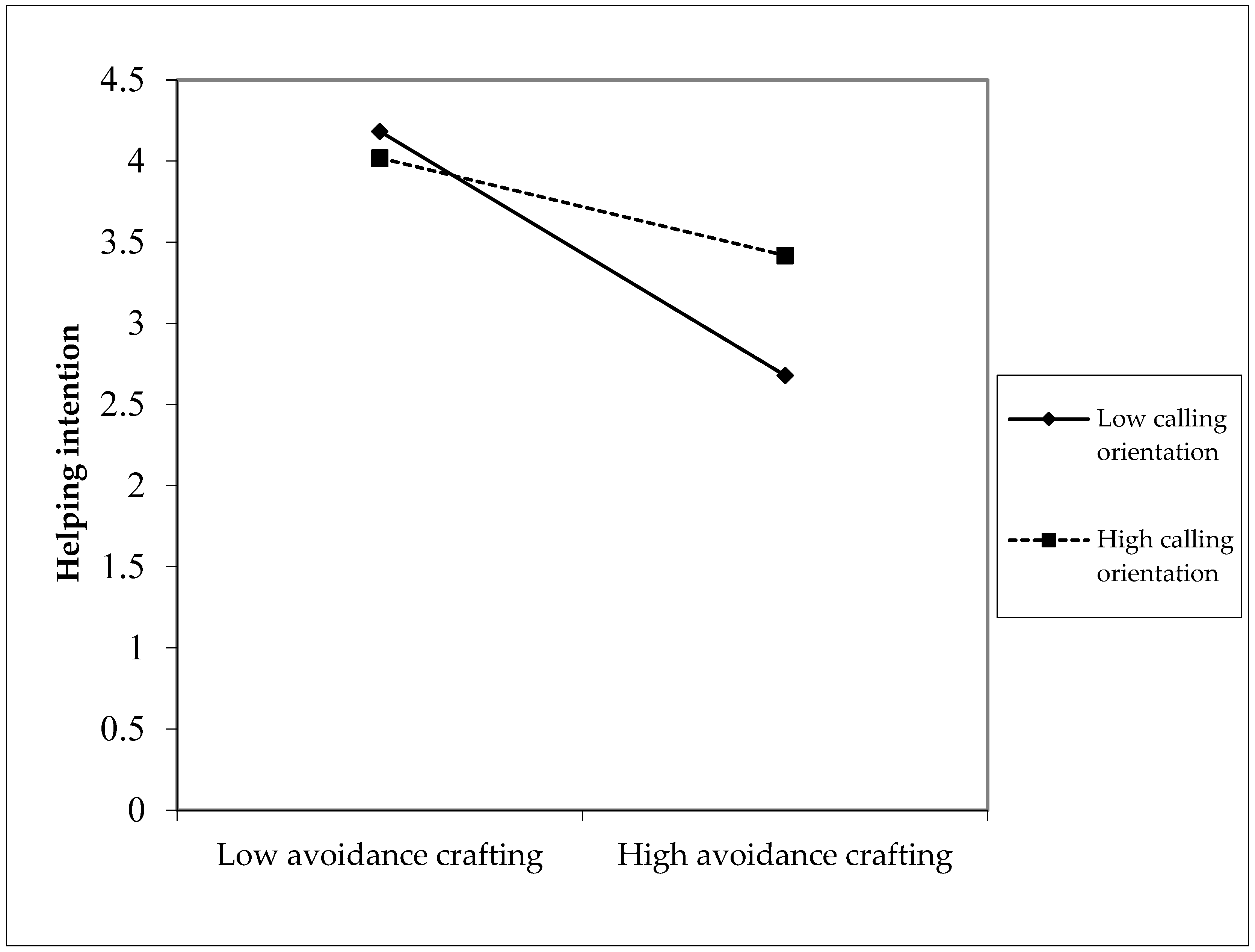

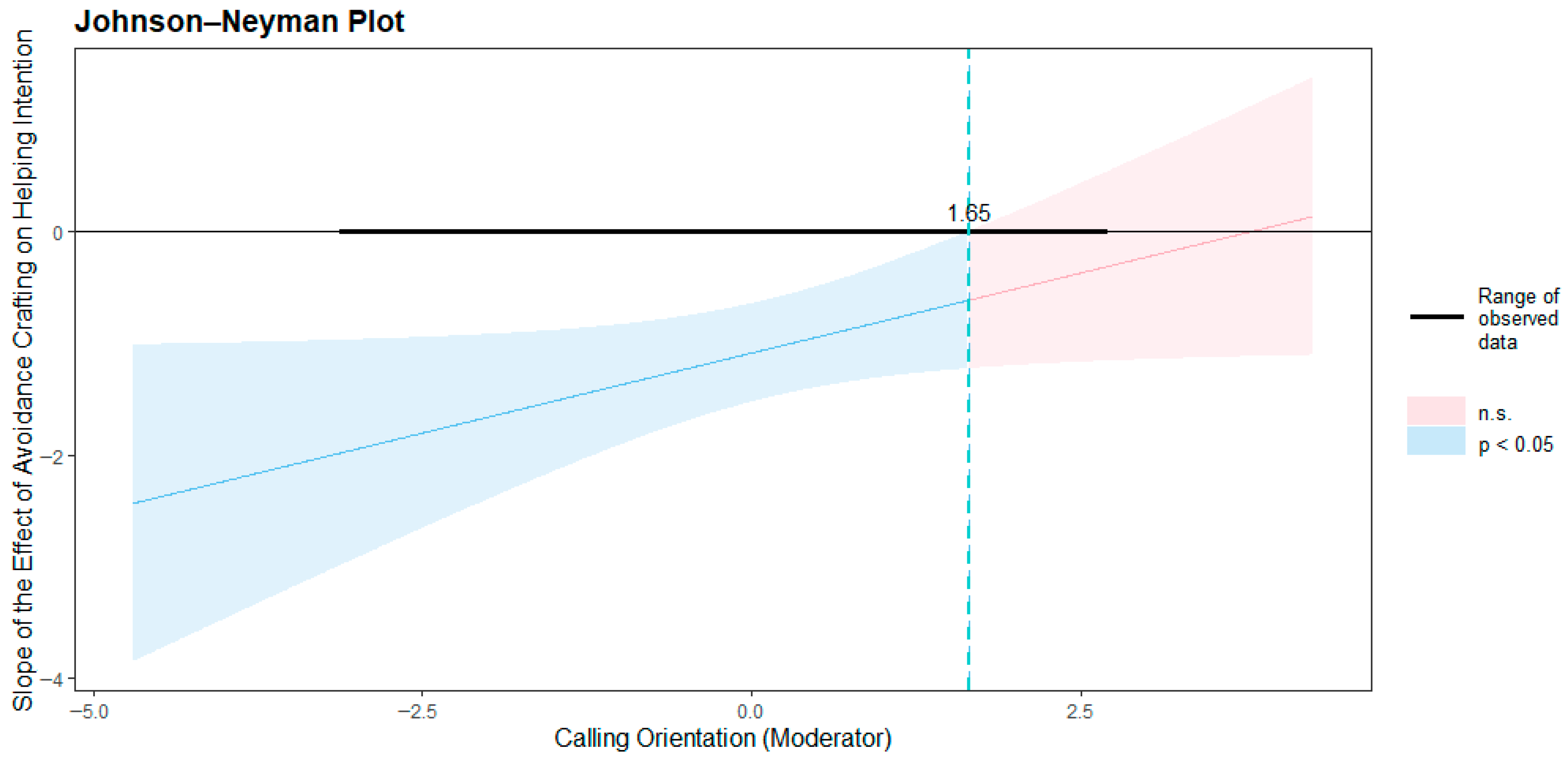

| Model 3 | ||||||

| Intercept | 4.11 | 0.16 | 26.48 | [3.80, 4.42] | <0.001 | |

| Avoidance crafting condition | −1.09 | −0.50 | 0.22 | −4.92 | [−1.53, −0.65] | <0.001 |

| Calling orientation | −0.05 | −0.08 | 0.10 | −0.53 | [−0.25, 0.15] | 0.601 |

| Avoidance × Calling orientation | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 2.04 | [0.01, 0.57] | 0.045 |

| R2 | 0.28 | |||||

| ∆R2 | 0.04 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, Y.K. The Role of Experienced Employees’ Calling Orientation in Shaping Responses to Newcomers’ Approach- and Avoidance-Oriented Job Crafting: A Vignette-Based Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10076. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210076

Kim YK. The Role of Experienced Employees’ Calling Orientation in Shaping Responses to Newcomers’ Approach- and Avoidance-Oriented Job Crafting: A Vignette-Based Study. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10076. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210076

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Ye Kang. 2025. "The Role of Experienced Employees’ Calling Orientation in Shaping Responses to Newcomers’ Approach- and Avoidance-Oriented Job Crafting: A Vignette-Based Study" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10076. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210076

APA StyleKim, Y. K. (2025). The Role of Experienced Employees’ Calling Orientation in Shaping Responses to Newcomers’ Approach- and Avoidance-Oriented Job Crafting: A Vignette-Based Study. Sustainability, 17(22), 10076. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210076

_Li.png)