Exploring Impact and Driving Forces of Land Use Transformation on Ecological Environment in Urban Agglomeration from the Perspective of Production-Living-Ecological Spatial Synergy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Region

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Changes in Land Utilization

2.2.2. Ecological Quality Status

2.2.3. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

2.2.4. Ecological Contribution Rate

2.2.5. Identification of Driving Factors

Selection of Impact Factors

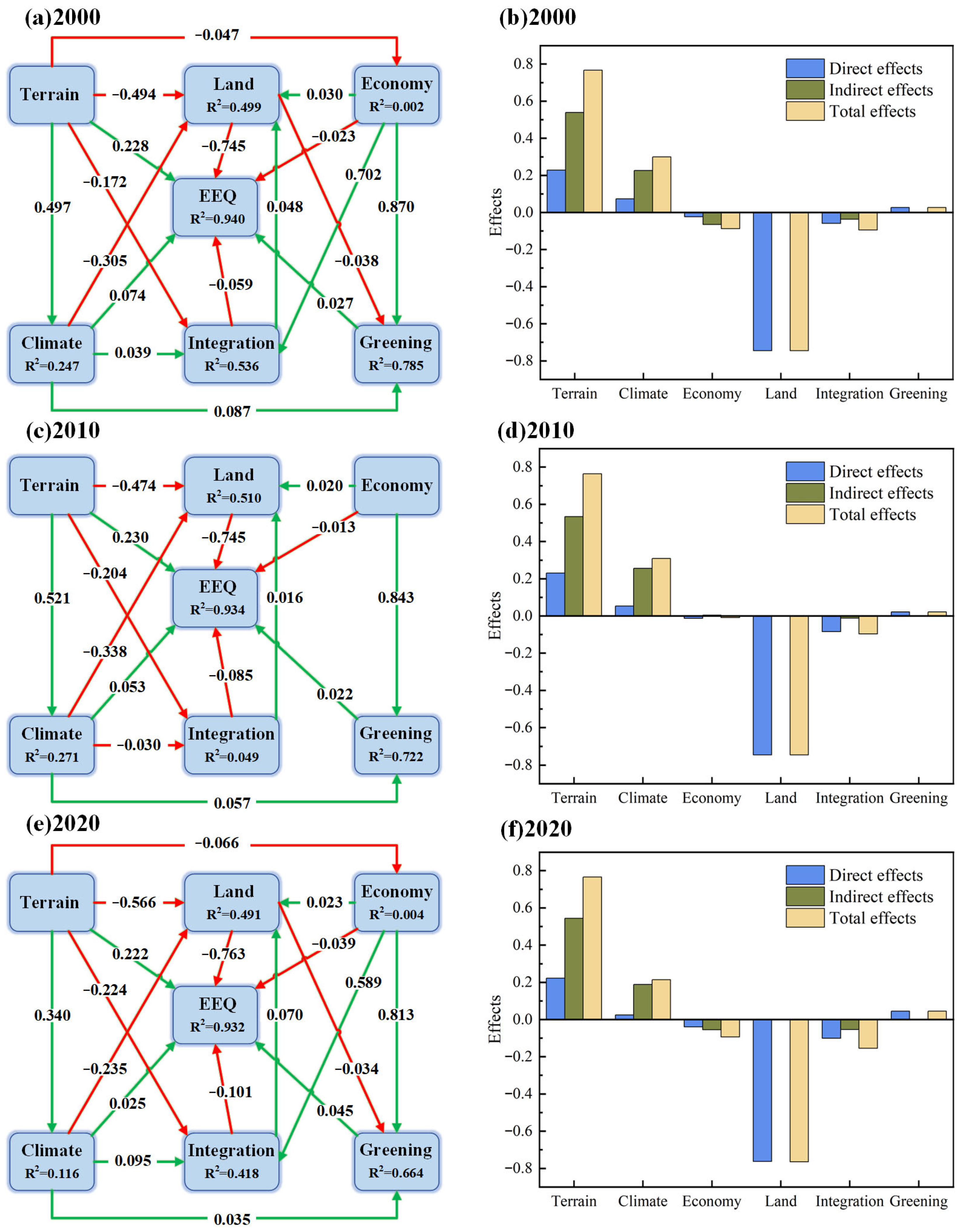

Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modeling

2.3. Sources and Handling of Data

2.3.1. Land Use Type Data

2.3.2. Other Data

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Land Use Change

3.2. Eco-Environmental Effects

3.2.1. Spatiotemporal Variation in EEQ

3.2.2. Spatial Autocorrelation of EEQ

3.2.3. Ecological Contribution Rate of Production-Living-Ecological Space Transformation

3.3. Analysis of Factors Affecting EEQ

4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact of LUT on the Ecological Environment

4.2. Multi-Factor Driving Mechanism: An Empirical Analysis Based on Structural Equation Modeling

4.3. Policy Recommendations

4.4. Limitations and Prospective Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| VIF | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation | 2.127 | 2.131 | 2.128 |

| Slope | 2.127 | 2.131 | 2.128 |

| GDP per capita | 2.023 | 3.871 | 2.190 |

| Urbanization rate | 2.368 | 4.378 | 2.697 |

| The proportion of tertiary industry | 1.677 | 1.773 | 1.809 |

| Relative humidity | 1.935 | 1.505 | 1.759 |

| Average annual precipitation | 1.935 | 1.505 | 1.759 |

| Number of parks | 1.196 | 1.250 | 2.808 |

| Green coverage area | 1.196 | 1.250 | 2.808 |

| Strength of inter-city linkages | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Proportion of agricultural production land | 1.022 | 1.000 | 1.006 |

| Land development intensity | 1.022 | 1.000 | 1.006 |

| Year | Path | Path Coefficient | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Terrain | →EEQ | 0.228 | *** |

| →Climate | 0.497 | *** | ||

| →Economy | −0.047 | *** | ||

| →Integration | −0.172 | *** | ||

| →Land | −0.049 | *** | ||

| Climate | →EEQ | 0.074 | *** | |

| →Greening | 0.087 | *** | ||

| →Integration | 0.039 | *** | ||

| →Land | −0.305 | *** | ||

| Economy | →EEQ | −0.023 | *** | |

| →Greening | 0.870 | *** | ||

| →Integration | 0.702 | *** | ||

| →Land | 0.030 | *** | ||

| Greening | →EEQ | 0.027 | *** | |

| Integration | →EEQ | −0.059 | *** | |

| →Land | 0.048 | *** | ||

| Land | →EEQ | −0.745 | *** | |

| →Greening | −0.038 | *** | ||

| 2010 | Terrain | →EEQ | 0.230 | *** |

| →Climate | 0.521 | *** | ||

| →Integration | −0.204 | *** | ||

| →Land | −0.474 | *** | ||

| Climate | →EEQ | 0.053 | *** | |

| →Greening | 0.057 | *** | ||

| →Integration | −0.030 | *** | ||

| →Land | −0.338 | *** | ||

| Economy | →EEQ | −0.013 | *** | |

| →Greening | 0.843 | *** | ||

| →Land | 0.020 | *** | ||

| Greening | →EEQ | 0.022 | *** | |

| Integration | →EEQ | −0.085 | *** | |

| →Land | 0.016 | ** | ||

| Land | →EEQ | −0.745 | *** | |

| 2020 | Terrain | →EEQ | 0.222 | *** |

| →Climate | 0.340 | *** | ||

| →Economy | −0.066 | *** | ||

| →Integration | −0.224 | *** | ||

| →Land | −0.566 | *** | ||

| Climate | →EEQ | 0.025 | *** | |

| →Greening | 0.035 | *** | ||

| →Integration | 0.095 | *** | ||

| →Land | −0.235 | *** | ||

| Economy | →EEQ | −0.039 | *** | |

| →Greening | 0.813 | *** | ||

| →Integration | 0.589 | *** | ||

| →Land | 0.023 | *** | ||

| Greening | →EEQ | 0.045 | *** | |

| Integration | →EEQ | −0.101 | *** | |

| →Land | 0.070 | *** | ||

| Land | →EEQ | −0.763 | *** | |

| →Greening | −0.034 | *** |

| Year | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Loading | AVE | CR | Loading | AVE | CR | Loading | AVE | CR |

| Terrain | 0.864 | 0.927 | 0.864 | 0.927 | 0.864 | 0.927 | |||

| Elevation | 0.926 | 0.926 | 0.926 | ||||||

| Slope | 0.932 | 0.933 | 0.933 | ||||||

| Economy | 0.746 | 0.898 | 0.804 | 0.925 | 0.766 | 0.908 | |||

| GDP per capita | 0.870 | 0.904 | 0.877 | ||||||

| Urbanization rate | 0.894 | 0.930 | 0.905 | ||||||

| The proportion of tertiary industry | 0.825 | 0.853 | 0.843 | ||||||

| Climate | 0.845 | 0.916 | 0.775 | 0.872 | 0.826 | 0.904 | |||

| Relative humidity | 0.896 | 0.803 | 0.881 | ||||||

| Average annual precipitation | 0.942 | 0.951 | 0.935 | ||||||

| Greening | 0.688 | 0.812 | 0.719 | 0.836 | 0.901 | 0.948 | |||

| Number of parks | 0.927 | 0.899 | 0.957 | ||||||

| Green coverage area | 0.718 | 0.793 | 0.942 | ||||||

| Integration | / | / | / | / | / | / | |||

| Strength of inter-city linkages | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| Land | 0.567 | 0.717 | 0.505 | 0.666 | 0.463 | 0.631 | |||

| Proportion of agricultural production land | 0.875 | 0.803 | 0.745 | ||||||

| Land development intensity | 0.607 | 0.604 | 0.609 | ||||||

References

- Long, H. Land use policy in China: Introduction. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Evolution of habitat quality and association with land-use changes in mountainous areas: A case study of the Taihang Mountains in Hebei Province, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Liu, Y.; Hou, X.; Li, T.; Li, Y. Effects of land use transitions due to rapid urbanization on ecosystem services: Implications for urban planning in the new developing area of China. Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hualou, L.; Yi, Q.; Shuangshuang, T.; Yurui, L.; Dazhuan, G.; Yingnan, Z.; Li, M.; Wenjie, W.; Jing, W. Land use transitions under urbanization and their environmental effects in the farming areas of China: Research progress and prospect. Adv. Earth Sci. 2018, 33, 455. [Google Scholar]

- Grainger, A. National land use morphology: Patterns and possibilities. Geography 1995, 80, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Zhang, F.; Ma, L. Changes of production-living-ecology land transformation and eco-environmental effects in Xinjiang in last 40 years. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 53, 514–523. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Duan, X.; Wang, L.; Jin, Z. Land use transformation based on ecological-production-living spaces and associated eco-environment effects: A case study in the Yangtze River Delta. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2018, 38, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lambin, E.F.; Meyfroidt, P. Land use transitions: Socio-ecological feedback versus socio-economic change. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Ma, L.; Zhou, G. Land use transition research in China: Progress, challenges and prospect. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2025, 80, 1993–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Chen, K. Urban-rural integrated development and land use transitions: A perspective of land system science. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2021, 76, 295–309. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H. Explanation of Land Use Transitions. China Land Sci. 2022, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H. Land use transition and rural transformation development. Prog. Geogr. 2012, 31, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Jilai, L.; Yansui, L.; Yurui, L. Classification evaluation and spatial-temporal analysis of “production-living-ecological” spaces in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 1290–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, G.; Guo, B.; Cheng, J.; Deng, X.; Wu, F. Layout optimization and support system of territorial space: An analysis framework based on resource efficiency. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 534–546. [Google Scholar]

- Gou, M.-M.; Liu, C.-F.; Li, L.; Xiao, W.-F.; Wang, N.; Hu, J.-W. Ecosystem service value effects of the Three Gorges Reservoir Area land use transformation under the perspective of “production-living-ecological” space. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 32, 3933–3941. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, C.; Cheng, L.; Shao, Y. Efficiency Characteristics and Evolution Patterns of Urban Carbon Metabolism of Production-Living-Ecological Space in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region. Environ. Sci. 2024, 45, 1254–1264. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z.; Wan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Ren, P. Analysis and simulation prediction of the evolutionary characteristics of the living-production-ecological spatial conflicts in the agriculture-pastoral ecotone in western Sichuan: Taking four counties in Aba Prefecture as examples. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 6243–6256. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Pu, X.; Yang, P.; Luo, C. Identification and Spatial-Temporal Evolution Analysis of “Production-Living-Ecological” Space in Karst Area—A Case Study of Huaxi District, Guiyang City. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2023, 38, 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, C.; Jia, K.; Li, G.; Wang, Y. Theoretical analysis of the index system and calculation model of carrying capacity of land ecological-production-living spaces from county scale. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2017, 37, 5198–5209. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Z.; Wan, J.; Meng, B. Interpretation of mountain territory space and its optimized conceptual model and theoretical framework. Mt. Res. 2017, 35, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hongqi, Z.; Erqi, X.; Huiyi, Z. Ecological-living-productive land classification system in China. J. Resour. Ecol. 2017, 8, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Wang, H.; Huang, A.; Xu, Y.; Lu, L.; Ji, Z. Identification and spatial-temporal evolution of rural “production-living-ecological” space from the perspective of villagers’ behavior—A case study of Ertai Town, Zhangjiakou City. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Wang, Q. Quantitative recognition and characteristic analysis of production-living-ecological space evolution for five resource-based cities: Zululand, Xuzhou, Lota, Surf Coast and Ruhr. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, S.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W. Identification of land use conflicts in China’s coastal zones: From the perspective of ecological security. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 213, 105841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bao, W.; Liu, Y. Coupling coordination analysis of rural production-living-ecological space in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Xu, J.; Lin, Z. Conflict or coordination? Assessing land use multi-functionalization using production-living-ecology analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 577, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, H.; Li, X. What is the future for production-living-ecological spaces in the Greater Bay Area? A multi-scenario perspective based on DEE. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 131, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Li, X.; Fan, H.; He, W. Spatial analysis of production-living-ecological functions and zoning method under symbiosis theory of Henan, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 69093–69110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asabere, S.B.; Acheampong, R.A.; Ashiagbor, G.; Beckers, S.C.; Keck, M.; Erasmi, S.; Schanze, J.; Sauer, D. Urbanization, land use transformation and spatio-environmental impacts: Analyses of trends and implications in major metropolitan regions of Ghana. Land Use Policy 2020, 96, 104707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Chi, G.; Li, J. The spatial association of ecosystem services with land use and land cover change at the county level in China, 1995–2015. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 669, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Long, H.; Li, T.; Tu, S. Land use transitions and their effects on water environment in Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, China. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, H.; Wang, Q. Spatiotemporal evolution of production–living–ecological land and its eco-environmental response in China’s coastal zone. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. A remote sensing index for assessment of regional ecological changes. China Environ. Sci. 2013, 33, 889–897. [Google Scholar]

- Pettorelli, N.; Vik, J.O.; Mysterud, A.; Gaillard, J.-M.; Tucker, C.J.; Stenseth, N.C. Using the satellite-derived NDVI to assess ecological responses to environmental change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S. Exploration of eco-environment and urbanization changes based on multi-source remote sensing data—A case study of Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Wang, B.; Liu, S.; Liu, C.; Wei, W.; Kauppi, P.E. Economical assessment of forest ecosystem services in China: Characteristics and implications. Ecol. Complex. 2012, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messer, L.C.; Jagai, J.S.; Rappazzo, K.M.; Lobdell, D.T. Construction of an environmental quality index for public health research. Environ. Health 2014, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wu, Z. Modelling and mapping trends in grain production growth in China. Outlook Agric. 2013, 42, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Ding, T.; Chen, J.; Xue, S.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Yang, S. Impacts of land use/land cover changes on ecosystem services in ecologically fragile regions. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Li, F.; Sun, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Hu, D. Assessment of land-use/cover changes and its ecological effect in rapidly urbanized areas—Taking Pearl River Delta urban agglomeration as a case. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fang, C.; Zhao, R.; Zhu, C.; Guan, J. Spatial–temporal evolution and driving force analysis of eco-quality in urban agglomerations in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 866, 161465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yang, J.; Yang, G.; Wu, C.; Yu, J. How do ecosystem service functions affect ecological health? Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt in China. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2024, 26, 2215–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Li, H.; Zhai, J. Spatio-temporal variation of potential evapotranspiration and climatic drivers in the Jing-Jin-Ji region, North China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 256, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Shao, H.; Xiang, X.; Yuan, L.; Zhou, Y.; Xian, W. A coupling method for eco-geological environmental safety assessment in mining areas using PCA and catastrophe theory. Nat. Resour. Res. 2020, 29, 4133–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Dai, A.; Dong, B. Changes in global vegetation activity and its driving factors during 1982–2013. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 249, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Han, J.; Huang, Y.; Fassnacht, S.R.; Xie, S.; Lv, E.; Chen, M. Vegetation response to climate conditions based on NDVI simulations using stepwise cluster analysis for the Three-River Headwaters region of China. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 92, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Tang, L. Interactive effects of natural and anthropogenic factors on heterogenetic accumulations of heavy metals in surface soils through geodetector analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 789, 147937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Lin, H.; An, X.; Chen, S.; Qi, S.; Zhang, M. Evaluation and analysis of ecosystem service value based on land use/cover change in Dongting Lake wetland. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortizas, A.M.; Horák-Terra, I.; Pérez-Rodríguez, M.; Bindler, R.; Cooke, C.A.; Kylander, M. Structural equation modeling of long-term controls on mercury and bromine accumulation in Pinheiro mire (Minas Gerais, Brazil). Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Fu, M.; Breuste, J. Dominant landscape indicators and their dominant areas influencing urban thermal environment based on structural equation model. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 111, 105992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Wang, Y.; Zameer, H. Can urban spatial structure adjustment mitigate air pollution effect of economic agglomeration? New evidence from the Yangtze River Delta region, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 57302–57315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.-n.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.-h.; Yao, C.-x.; Wang, Y. Impact of urbanization on supply and demand of typical ecosystem services in Yangtze River Delta. J. Nat. Resour. 2022, 37, 1555–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Che, L.; Zhou, L.; Xu, J. Spatio-temporal dynamic simulation of land use and ecological risk in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration, China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 31, 829–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Lu, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, X. Measurement of the eco-environmental effects of urban sprawl: Theoretical mechanism and spatiotemporal differentiation. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 105, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, W.; Shen, M.; Huang, Y.; Li, W.; Qian, Y. Transformation of China’s urbanization and eco-environment dynamics: An insight with location-based population-weighted indicators. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 16558–16567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Lv, T.; Zhang, X.; Xie, H.; Fu, S.; Geng, C.; Li, Z. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity and decoupling decomposition of industrial carbon emissions in the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration of China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 50412–50430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Sha, Y.; Chen, Y. The coupling coordination and influencing factors of urbanization and ecological resilience in the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration, China. Land 2024, 13, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Li, X. Discussion on the index method of regional land use change. ACTA Geogr. Sin. Chin. Ed. 2003, 58, 643–650. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Cheng, W.-S.; Li, X.-D.; Yang, C.-Y.; Huang, Q.-Q. Recognition on the changes and driving factors of eco-environmental effect of land use transformation in arid inland river basin. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2023, 30, 324–332. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Lu, H.; Ji, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, C. Exploring evolution characteristics of eco-environment quality in the Yangtze River Basin based on remote sensing ecological index. Heliyon 2023, 9, e23243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaker, R.R.; Aversa, J.; Papp, V.; Serre, B.M.; Mackay, B.R. Showcasing relationships between neighborhood design and wellbeing Toronto indicators. Sustainability 2020, 12, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ao, Y.; Han, L.; Kang, S.; Sun, Y. Effects of human activity intensity on habitat quality based on nighttime light remote sensing: A case study of Northern Shaanxi, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, D.; Luo, Y.; Gu, K. Spatio-temporal Differentiation and Driving Forces of Eco-Environmental Effects of Land Use Transformation in Yangtze River Delta Economic Zone: A Perspective of “Production-Living-Ecological” Spaces. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2023, 32, 1664–1676. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, X.; Du, X.; Duan, C.; Peng, L. Evaluation of ecological environment quality and analysis of influencing factors in Wuhan City based on RSEI. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yu, J.; Xu, W.; Wu, Y.; Lei, X.; Ye, J.; Geng, J.; Ding, Z. Long-time series ecological environment quality monitoring and cause analysis in the Dianchi Lake Basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 148, 110084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Ou, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Tang, L. Multidimensional Analysis of Urban Spatial Interaction in the Yangtze River Delta. Geogr. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2022, 38, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Xue, D.; Dong, C.; Wang, C.; Zhang, C.; Ma, B.; Song, Y. Eco-environmental effects and spatial differentiation mechanism of land use transition in agricultural areas of arid oasis: A perspective based on the dominant function of production-living-ecological spaces. Prog. Geogr. 2022, 41, 2044–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xiang, W. Spatial connection intensity of central cities in Guanzhong Plain City Group. Arid Land Geogr. 2020, 43, 1593–1602. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, M.; Lu, Y.; Wei, L. Evolution of Spatial Association Network of Cities in Yangtze River Delta and Its Influencing Factors--Based on Modified Gravity Model. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2025, 34, 1426–1440. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, F.; Gu, J.; Lv, X.; Zhou, S. Study on regional integration process of Changsha-Zhuzhou-Xiangtan urban agglomeration under the perspective of new regionalism. Hum. Geogr. 2018, 33, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Kang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y. The impact of land-use change on the ecological environment quality from the perspective of production-living-ecological space: A case study of the northern slope of Tianshan Mountains. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 83, 102795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Chen, L.; Li, L.; Zhang, T.; Yuan, L.; Liu, R.; Wang, Z.; Zang, J.; Shi, S. Spatiotemporal characterization of the urban expansion patterns in the Yangtze River Delta region. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, S.; Zhong, Q.; Zhu, K.; Fu, H. Assessing Eco-Environmental Effects and Its Impacts Mechanisms in the Mountainous City: Insights from Ecological-Production-Living Spaces Using Machine Learning Models in Chongqing. Land 2024, 13, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, W.; Lu, Y. Land use transformation based on production-living-ecological space and associated eco-environment effects: A case study in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration. Land 2022, 11, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Song, Y.; Shao, Z.; Zheng, C.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. Exploring the causal relationships and pathways between ecological environmental quality and influencing Factors: A comprehensive analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 165, 112192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanishakib, F.; Salmanmahiny, A.; Mirkarimi, S.H.; Poodat, F. Hydrological connectivity assessment of landscape ecological network to mitigate development impacts. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Dong, W.; Liu, T.; Fang, L. Exploring ecosystem sensitivity patterns in China: A quantitative analysis using the Importance-Vulnerability-Sensitivity framework and neighborhood effects method. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Liu, M.; Wen, L.; Zhang, A. Does urbanization inevitably exacerbate cropland pressure? The multiscale evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 504, 145413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhuo, J.; Mao, Y. Driving the Evolution of Land Use Patterns: The Impact of Urban Agglomeration Construction Land in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Land 2024, 13, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Yang, R. Influence mechanism of production-living-ecological space changes in the urbanization process of Guangdong Province, China. Land 2021, 10, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Das, A.; Pereira, P. Impact of urbanization induced land use and land cover change on ecological space quality-mapping and assessment in Delhi (India). Urban Clim. 2024, 53, 101818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Tu, P.; Zhong, Y.; Huang, C.; Pan, X.; Xu, K.; Hong, S. Evaluating the effects of future urban expansion on ecosystem services in the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration under the shared socioeconomic pathways. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Xu, Q.; Yu, J.; Chen, L.; Peng, Y. Multiscale assessment of the spatiotemporal coupling relationship between urbanization and ecosystem service value along an urban–rural gradient: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Shen, A.; Liu, C.; Wen, B. Impacts of ecological land fragmentation on habitat quality in the Taihu Lake basin in Jiangsu Province, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Wei, G. Assessment of ecological resilience and its response mechanism to land spatial structure conflicts in China’s Southeast Coastal Areas. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 170, 112980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nie, W.; Zhang, M.; Wang, L.; Dong, H.; Xu, B. Assessment and optimization of urban ecological network resilience based on disturbance scenario simulations: A case study of Nanjing city. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 438, 140812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, E.; Zhang, C.; Liu, C.; Li, J. Multi-scenario simulation of land use change and ecosystem service value based on the markov–FLUS model in Ezhou city, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Hu, H.; Han, H.; Zhang, X.; Fan, H.; Yan, K. Towards sustainability: The spatiotemporal patterns and influence mechanism of urban sprawl intensity in the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration. Habitat Int. 2024, 148, 103089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Tasser, E.; Borsky, S.; Braun, M.; Eitzinger, J.; Gaube, V.; Getzner, M.; Glatzel, S.; Gschwantner, T.; Kirchner, M. Past and future impacts of land-use changes on ecosystem services in Austria. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Jiang, E.; Tian, S.; Qu, B.; Li, J.; Hao, L.; Liu, C.; Jing, Y. Land-Use Transformation and Its Eco-Environmental Effects of Production–Living–Ecological Space Based on the County Level in the Yellow River Basin. Land 2025, 14, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Chen, F.; Sun, Y.; Ma, J.; Yang, Y.; Shi, G. Effects of land utilization transformation on ecosystem services in urban agglomeration on the northern slope of the Tianshan Mountains, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 162, 112046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wen, Z.; Chen, S.; Ding, S.; Zhang, M. Quantifying land use/land cover and landscape pattern changes and impacts on ecosystem services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, J.; Xiang, H. Change and driving factors of eco-environmental quality in Beijing green belts: From the perspective of Nature-based Solutions. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruhan; Liu, D. Study on the influencing factors of the evolution of space pattern based on principal component analysis in Duolun County. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Teng, T.; Wang, S.; Wang, T. Impact and mechanism of urbanization on urban green development in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, L.; Tao, Z.; Wan, B.; Wang, Y.; Tang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Effect of urbanization and urban forests on water quality improvement in the Yangtze River Delta: A case study in Hangzhou, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Qiao, J.; Li, M.; Dun, Y.; Zhu, X.; Ji, X. Spatiotemporal evolution of ecological environmental quality and its dynamic relationships with landscape pattern in the Zhengzhou Metropolitan Area: A perspective based on nonlinear effects and spatiotemporal heterogeneity. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 480, 144102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Li, L.; Zuo, J.; Gao, F.; Ma, X.; Shen, X.; Zheng, Y. Regional integration policies and urban green innovation: Fresh evidence from urban agglomeration expansion. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 354, 120485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Lee, C.-C.; Peng, D. Does regional integration improve economic resilience? Evidence from urban agglomerations in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 88, 104273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Niu, S.; Miao, M. Urban economic resilience within the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration: Exploring spatially correlated network and spatial heterogeneity. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 103, 105270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Jiang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Lin, A.; Zhou, H.; Cen, L. Analyzing multiscale associations and couplings between integrated development and eco-environmental systems: A case study of the central plains urban agglomeration, China. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 171, 103387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y.; He, D.; Deng, B.; Zhang, E.; Wei, S.; Duan, X. Dynamic monitoring of eco-environmental quality in the Greater Mekong Subregion: Evolutionary characteristics and country differences. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 110, 107700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yan, K.; Shi, Y.; Lv, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X. Decrypting resilience: The spatiotemporal evolution and driving factors of ecological resilience in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 106, 107540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, R.R.; Rybarczyk, G.; Brown, C.; Papp, V.; Alkins, S. (Re) emphasizing urban infrastructure resilience via scoping review and content analysis. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Liu, H.; Li, S.; Luo, Q.; Cheng, S.; Hu, G.; Wang, X.; Bai, W. Coupling coordination analysis of urbanization and ecological environment in Chengdu-Chongqing urban agglomeration. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 161, 111969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wu, J.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Chen, W.; Pan, S. Identifying the Interactive Coercive Relationships Between Urbanization and Eco-Environmental Quality in the Yangtze and Yellow River Basins, China. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Lan, T.; Xing, X.; Xie, T.; Li, W.; Fang, C.; Cao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, D.; Wang, L.; et al. Past achievements and future strategies of eco-environmental construction in mega urban agglomerations in eastern China. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2023, 38, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ge, Q. Ecological resilience of three major urban agglomerations in China from the “environment–society” coupling perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 169, 112944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latent Variable | Manifest Variable |

|---|---|

| Terrain | Elevation |

| Slope | |

| Economy | GDP per capita |

| Urbanization rate | |

| The proportion of tertiary industry | |

| Climate | Average annual precipitation |

| Relative humidity | |

| Greening | Number of parks |

| Green coverage area | |

| Integration | Strength of inter-city linkages |

| Land | Proportion of agricultural production land |

| Land development intensity |

| Production-Living-Ecological Space Land Use Classification | Secondary Land Use Date Type | |

|---|---|---|

| First Classification | Secondary Land Classification | |

| Production land | Agricultural production land (APL) | Paddy field, dry land |

| Industrial production land (IPL) | Industrial, mining and transportation construction land | |

| Living land | Urban living land (ULL) | Urban land |

| Rural living land (RLL) | Rural residential area | |

| Ecological land | Forest ecological land (FEL) | Sparse woodland, shrubbery, woodland, other woodland |

| Pasture ecological land (PEL) | Low coverage grassland, medium coverage grassland, high coverage grassland | |

| Water ecological land (WEL) | Rivers, lakes, reservoirs, ponds, permanent glaciers, snow, beaches | |

| Other ecological land (OEL) | Marshland, bare rocky gravel land, Gobi, sandy land, beach land, saline-alkali land, bare land, alpine desert | |

| Date | Resolution | Unit | Year | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation | 30 m | m | 2000, 2010, 2020 | Geospatial Data Cloud |

| Slope | 30 m | % | 2000, 2010, 2020 | Geospatial Data Cloud |

| GDP per capita | City scale | yuan | 2000, 2010, 2020 | National Bureau of Statistics |

| Urbanization rate | City scale | % | 2000, 2010, 2020 | National Bureau of Statistics |

| The proportion of tertiary industry | City scale | % | 2000, 2010, 2020 | National Bureau of Statistics |

| Relative humidity | 1000 m | % | 2000, 2010, 2020 | WorldClim Global Climate Database |

| Average annual precipitation | 1000 m | mm | 2000, 2010, 2020 | WorldClim Global Climate Database |

| Number of parks | City scale | count | 2000, 2010, 2020 | National Bureau of Statistics |

| Green coverage area | City scale | ha | 2000, 2010, 2020 | National Bureau of Statistics |

| GDP | City scale | 108 yuan | 2000, 2010, 2020 | National Bureau of Statistics |

| Land Use Type | 2000 (km2) | 2010 (km2) | 2020 (km2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| APL | 111,084.25 | 101,744.89 | 97,849.10 |

| FEL | 57,779.72 | 57,040.49 | 57,010.93 |

| PEL | 7911.25 | 7353.28 | 7651.91 |

| WEL | 18,449.20 | 20,363.44 | 19,417.10 |

| ULL | 4272.90 | 9771.17 | 11,796.33 |

| RLL | 10,703.19 | 12,399.60 | 13,687.94 |

| IPL | 1341.26 | 2675.74 | 3874.94 |

| OEL | 35.12 | 228.28 | 288.65 |

| Total | 211,576.89 | 211,576.89 | 211,576.89 |

| Types | Interval | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid (Number) | Area (km2) | Grid (Number) | Area (km2) | Grid (Number) | Area (km2) | ||

| Low-value zone | 0–0.21 | 696 | 6264 | 1943 | 17,487 | 2598 | 23,382 |

| Lower-value zone | 0.21–0.38 | 11,440 | 102,960 | 10,433 | 93,897 | 10,058 | 90,522 |

| Moderate-value zone | 0.38–0.55 | 3732 | 33,588 | 3818 | 34,362 | 3634 | 32,706 |

| Higher-value zone | 0.55–0.72 | 2761 | 24,849 | 2662 | 23,958 | 2686 | 24,174 |

| High-value zone | 0.72–0.89 | 6119 | 55,071 | 5992 | 53,928 | 6000 | 54,000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, L.; Wang, X.; Jiang, W.; Ren, M.; Yin, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B. Exploring Impact and Driving Forces of Land Use Transformation on Ecological Environment in Urban Agglomeration from the Perspective of Production-Living-Ecological Spatial Synergy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8235. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188235

Ren L, Wang X, Jiang W, Ren M, Yin L, Zhang X, Zhang B. Exploring Impact and Driving Forces of Land Use Transformation on Ecological Environment in Urban Agglomeration from the Perspective of Production-Living-Ecological Spatial Synergy. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8235. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188235

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Lihong, Xiaofang Wang, Wenhui Jiang, Mei Ren, Le Yin, Xiaobo Zhang, and Baolei Zhang. 2025. "Exploring Impact and Driving Forces of Land Use Transformation on Ecological Environment in Urban Agglomeration from the Perspective of Production-Living-Ecological Spatial Synergy" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8235. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188235

APA StyleRen, L., Wang, X., Jiang, W., Ren, M., Yin, L., Zhang, X., & Zhang, B. (2025). Exploring Impact and Driving Forces of Land Use Transformation on Ecological Environment in Urban Agglomeration from the Perspective of Production-Living-Ecological Spatial Synergy. Sustainability, 17(18), 8235. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188235