Corporate Social Responsibility of Foreign Multinationals in a Developing Country Context: Insights from Pakistan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Relevant Theoretical Perspectives

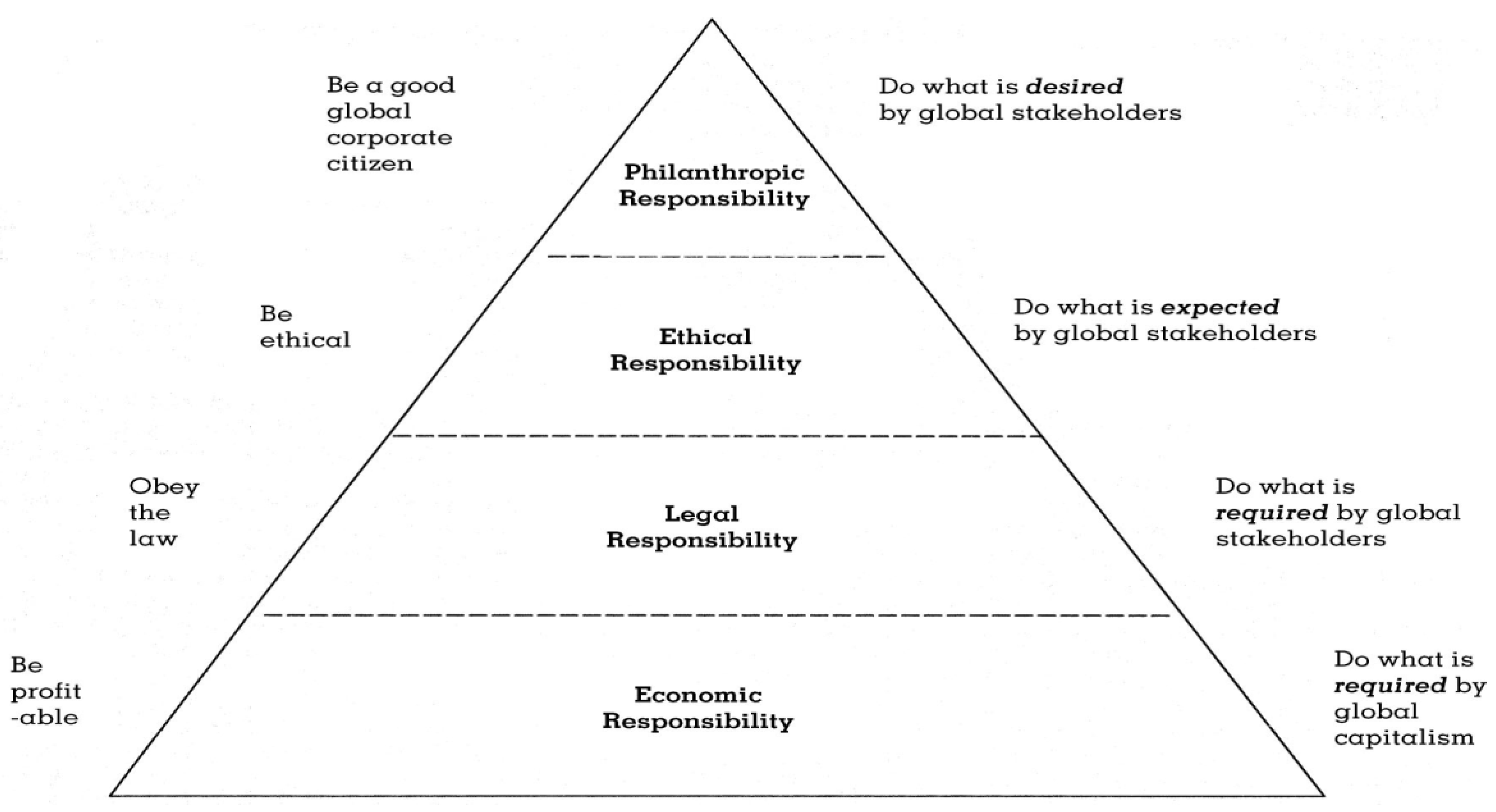

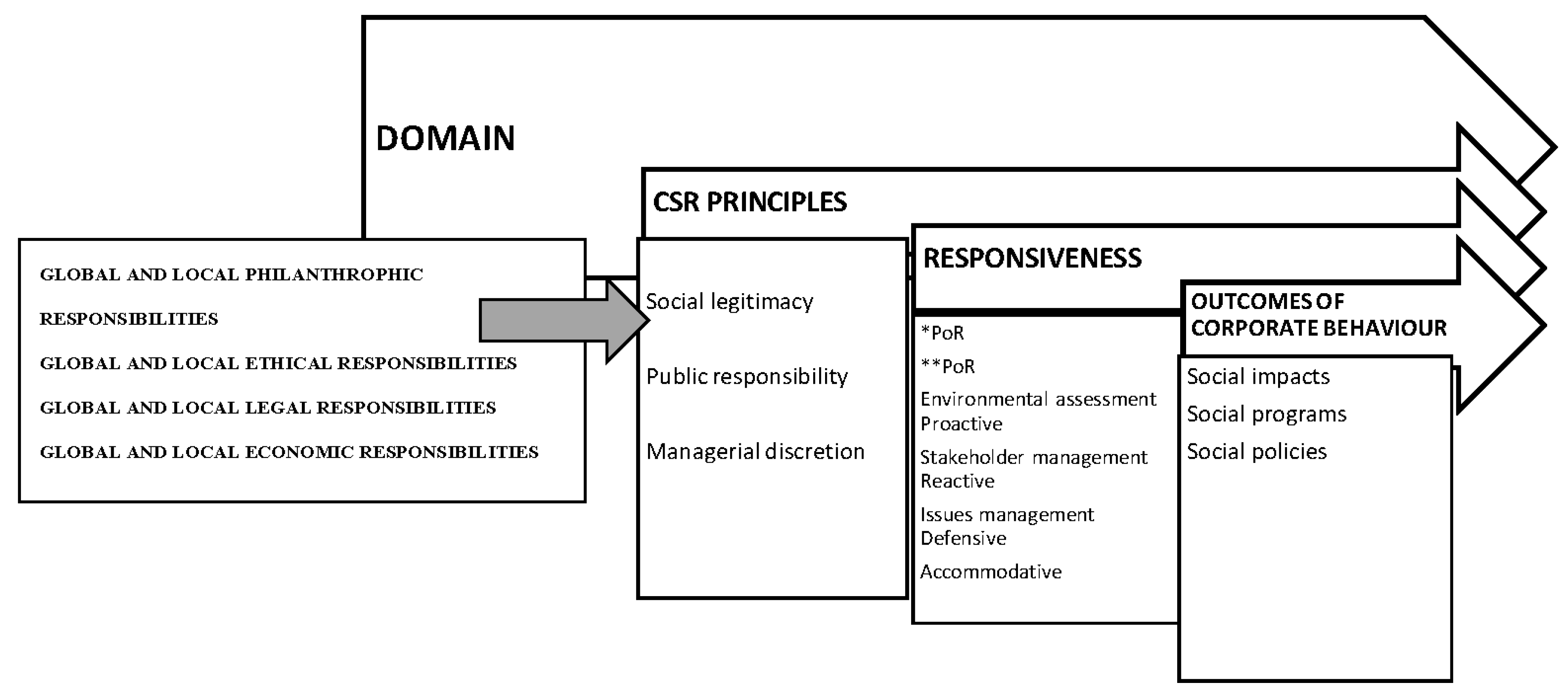

2.1. Proposed Model for This Research: A Global CSR Model

- MNCs should make profit according to expectations of the international community (including the international business community).

- MNCs should comply with international and host country laws.

- MNCs should consider both global and host country ethical standards.

- MNCs should meet host country expectations in relation to good corporate citizenship.

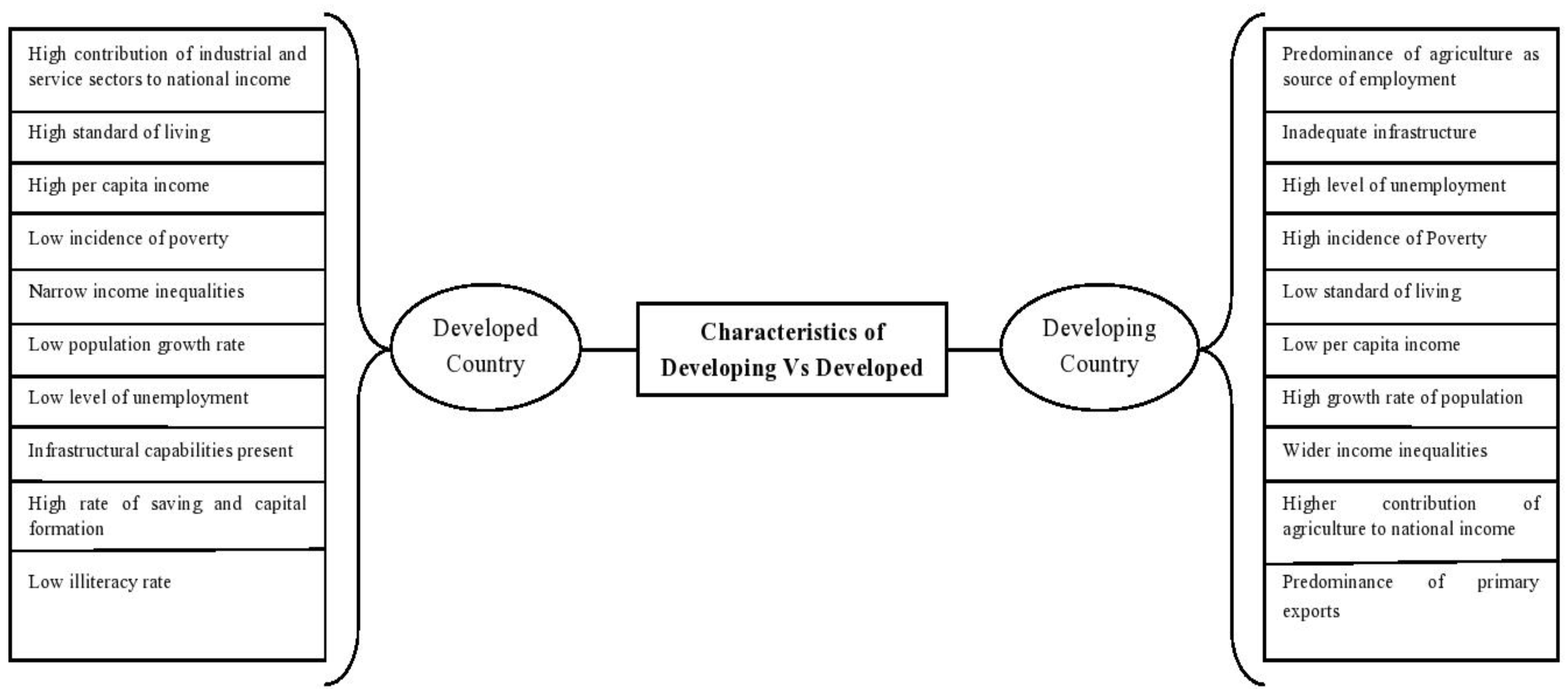

2.2. Contextual Background-Pakistan

3. Research Methodology

4. Research Findings

4.1. CSR Conceptualisation

4.2. Motivation for CSR Practices

4.3. Corporate Social Responsiveness Strategies

4.4. Outcomes of CSR Practices

5. Discussion on Empirical Findings

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pieterse, J.N. Globalization and Culture: Global Mélange; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Geppert, M.; Dörrenbächer, C. Politics and power in the multinational corporation: An introduction. In Politics and Power in the Multinational Corporation: The Role of Institutions, Interests and Identities; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Karam, C.M.; Jamali, D. A cross-cultural and feminist perspective on CSR in developing countries: Uncovering latent power dynamics. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 142, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, G.; Rathert, N. Multinational Corporations and CSR: Institutional Perspectives on Private Governance. 2015. Available online: http://ilera2015.com/dynamic/full/IL204.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2017).

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G.; Baumann, D. Global rules and private actors: Toward a new role of the transnational corporation in global governance. Bus. Ethics Q. 2006, 16, 505–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T.; Sanchez-Mangas, R.; Bélanger, J.; McDonnell, A. Why are some subsidiaries of multinationals the source of novel practices while others are not? National, corporate and functional influences. Br. J. Manag. 2015, 26, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kostova, T.; Marano, V.; Tallman, S. Headquarters–subsidiary relationships in MNCs: Fifty years of evolving research. J. World Bus. 2016, 51, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Brooks, C.; Pavelin, S. Corporate social performance and stock returns: UK evidence from disaggregate measures. Financ. Manag. 2006, 35, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.P.; Guay, T.R. Corporate social responsibility, public policy, and NGO activism in Europe and the United States: An Institutional-Stakeholder perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ralston, D.A. Corporate social responsibility in Europe and the US: Insights from businesses’ self-presentations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2002, 33, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hah, K.; Freeman, S. Multinational enterprise subsidiaries and their CSR: A conceptual framework of the management of CSR in smaller emerging economies. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Lew, Y.K.; Park, B.I. Institutional legitimacy and norms-based CSR marketing practices: Insights from MNCs operating in a developing economy. Int. Mark. Rev. 2015, 32, 463–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D. MNCs and International Accountability Standards Through an Institutional Lens: Evidence of Symbolic Conformity or Decoupling. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 617–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D. The CSR of MNC Subsidiaries in Developing Countries: Global, Local, Substantive or Diluted? J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Jamali, D. Strategic corporate social responsibility of multinational companies subsidiaries in emerging markets: Evidence from China. Long Range Plan. 2016, 49, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, W.; Moon, J. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in Asia. Bus. Soc. 2005, 44, 415–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P.; Siegel, D.S.; Hillman, A.; Eden, L. Three lenses on the multinational enterprise: Politics, corruption, and corporate social responsibility. Palgrave Macmillan J. 2006, 37, 733–746. [Google Scholar]

- Garriga, E.; Melé, D. Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Mirshak, R. Corporate social responsibility (CSR): Theory and practice in a developing country context. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 72, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Liu, X.; Wright, M.; Filatotchev, I. International experience and FDI location choices of Chinese firms: The moderating effects of home country government support and host country institutions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 45, 428–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meyer, K.E. Perspectives on multinational enterprises in emerging economies. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2004, 35, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’callaghan, T. Disciplining multinational enterprises: The regulatory power of reputation risk. Glob. Soc. 2007, 21, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunis, M.S. CSR research “Back Home”: A critical review of literature and future research options in Pakistan. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2009, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lauwo, S.G.; Otusanya, O.J.; Bakre, O. Corporate social responsibility reporting in the mining sector of Tanzania: (Lack of) government regulatory controls and NGO activism. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2016, 29, 1038–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, C. The new corporate citizenship of big business: Part of the solution to sustainability? Bus. Soc. Rev. 2000, 105, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detomasi, D.A. The multinational corporation and global governance: Modelling global public policy networks. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 71, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunis, M.S.; Durrani, L.; Khan, A. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Pakistan: A Critique of the Literature and Future Research Agenda. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2017, 9, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newenham-Kahindi, A.M. A global mining corporation and local communities in the lake Victoria zone: The case of Barrick Gold multinational in Tanzania. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 99, 253–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belal, A.R.; Cooper, S.M.; Roberts, R.W. Vulnerable and exploitable: The need for organizational accountability and transparency in emerging and less developed economies. Account. Forum 2013, 37, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idemudia, U. Corporate social responsibility and developing countries. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2011, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Neville, B. Convergence Versus Divergence of CSR in Developing Countries: An Embedded Multi-Layered Institutional Lens. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 599–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muthuri, J.N.; Gilbert, V. An Institutional Analysis of Corporate Social Responsibility in Kenya. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, L.A.; Nysten-haarala, S.; Tulaeva, S.; Tysiachniouk, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and the Oil Industry in the Russian Arctic: Global Norms and Neo-Paternalism. Eur.-Asia Stud. 2016, 68, 1340–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, M.; Park, S.H.; Zhou, N. MNC strategy and social adaptation in emerging markets. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 45, 842–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.W.; Allen, D.B. Corporate social responsibility in the multinational enterprise: Strategic and institutional approaches. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2006, 37, 838–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tan, J. Institutional structure and firm social performance in transitional economies: Evidence of multinational corporations in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Shen, X. CSR in China research: Salience, focus and nature. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, T.; Zaheer, S. Organizational legitimacy under conditions of complexity: The case of the multinational enterprise. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, N.; Papamichail, K.N.; Malik, K. Use of Social Media Applications for Supporting New Product Development Processes in Multinational Corporations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 120, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belal, A.; Owen, D.L. The rise and fall of stand-alone social reporting in a multinational subsidiary in Bangladesh: A case study. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2015, 28, 1160–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utting, P. Corporate responsibility and the movement of business. Dev. Pract. 2005, 15, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondy, K.; Starkey, K. The dilemmas of internationalization: Corporate social responsibility in the multinational corporation. Br. J. Manag. 2014, 25, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Islam, M.A.; Deegan, C. Media pressures and corporate disclosure of social responsibility performance information: A study of two global clothing and sports retail companies. Account. Bus. Res. 2010, 40, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Managing ethically with global stakeholders: A present and future challenge. Acad. Manag. Exec. (1993–2005) 2004, 18, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J. Corporate social performance revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 691–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, D.L. Addressing a theoretical problem by reorienting the corporate social performance model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, W.C. From CSR1 to CSR2: The maturing of business-and-society thought. Bus. Soc. 1994, 33, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. The case for and against business assumption of social responsibilities. Acad. Manag. J. 1973, 16, 312–322. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, L.; Post, J. Measuring corporate responsibility. J. Gen. Manag. 1975, 2, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, J.; Meehan, K.; RICHARDS, A. Corporate social responsibility: The 3C-SR model. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2006, 33, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agle, B.R.; Kelley, P.C. Ensuring validity in the measurement of corporate social performance: Lessons from corporate United Way and PAC campaigns. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 31, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J.; Jones, R.E. Stakeholder mismatching: A theoretical problem in empirical research on corporate social performance. Int. J. Org. Anal. 1995, 3, 229–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupperle, K.E.; Carroll, A.B.; Hatfield, J.D. An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1985, 28, 446–463. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkston, T.S.; Carroll, A.B. Corporate citizenship perspectives and foreign direct investment in the US. J. Bus. Ethics 1994, 13, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinelli, D.A.; Berry, M.A. Environmental citizenship in multinational corporations: Social responsibility and sustainable development. Eur. Manag. J. 2000, 18, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, R. The de-radicalization of corporate social responsibility. Crit. Soc. 2004, 30, 669–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.; Warren, D.E. The meaning and meaningfulness of corporate social initiatives. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2008, 113, 163–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.S.; Freeman, R.E. Stakeholders, social responsibility, and performance: Empirical evidence and theoretical perspectives. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 479–485. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M.A. Friedman doctrine: The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. N. Y. Times Mag. 1970, 13, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Pitman, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T.M. Corporate social responsibility revisited, redefined. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1980, 22, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L. Institutional analysis and the paradox of corporate social responsibility. Am. Behav. Sci. 2006, 49, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The corporate social performance–financial performance link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Monteiro, S.M.; GUZMÁN, B.A. The influence of the Portuguese environmental accounting standard on the environmental disclosures in the annual reports of large companies operating in Portugal: A first view (2002–2004). Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2010, 21, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, C.I.; Caraiani, C.; Dasclu, C. Research on Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2011, 13, 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolou, A.K.; Nanopoulos, K.A. Voluntary accounting disclosure and corporate governance: Evidence from Greek listed firms. Int. J. Account. Financ. 2009, 1, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, G.K.; Roberts, C.B.; Gray, S.J. Factors influencing voluntary annual report disclosures by US, UK and continental European multinational corporations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1995, 26, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghiemstra, R. Corporate communication and impression management–new perspectives why companies engage in corporate social reporting. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 27, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Pakistan, Ministry of Finance. Economic Survey of Pakistan Islamabad Pakistan 2016. Available online: http://www.finance.gov.pk/survey_1617.html (accessed on 20 June 2017).

- Ministry of Finance. Government of Pakistan Economic Survey 2005–2006. Available online: http://www.finance.gov.pk/survey/home.htm (accessed on 20 June 2017).

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavana, R.Y.; Delahaye, B.L.; Sekaran, U. Applied Business Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods; Wiley and Sons: Milton, Austrailia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Huberman, M.; Miles, M.B. The Qualitative Researcher’s Companion; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Begley, T.M.; Boyd, D.P. The need for a corporate global mind-set. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2003, 44, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, A.; Kolk, A. CSR performance in emerging markets evidence from Mexico. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartick, S.L. Issues Management: Corporate Fad or Corporate Function; Edison Electric Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Jamali, D.; Sidani, Y. Is CSR counterproductive in developing countries: The unheard voices of change. J. Chang. Manag. 2011, 11, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.R.; Lund-Thomsen, P. CSR as imperialism: Towards a phenomenological approach to CSR in the developing world. J. Chang. Manag. 2011, 11, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Principles of Corporate Social Responsibility |

|---|

| Institutional principle: legitimacy |

| Organizational principle: public responsibility |

| Individual principle: managerial discretion |

| Processes of Corporate Social Responsiveness |

| Environmental assessment |

| Stakeholder management |

| Issues management |

| Outcomes of Corporate Behavior |

| Social impacts |

| Social programs |

| Social policies |

| Company | Operations | Managerial Position | Duration of Interview | Subsidiary Office Location | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Tobacco & Cigarettes | CSR Manager | 55 m | Islamabad, Pakistan | UK |

| B | Oil & Gas Exploration and Production | CSR Manager | 90 m | Islamabad, Pakistan | Austria |

| C | Telecommunication Service Provider | Strategy Head | 50 m | Islamabad, Pakistan | China |

| D | Food and Beverages | CSR Manager | 77 m | Lahore, Pakistan | Switzerland |

| E | Telecommunication Hardware | Marketing Head | 140 m | Islamabad, Pakistan | China |

| F | Oil & Gas Exploration and Production | Production Manager | 110 m | Islamabad, Pakistan | US |

| G | Banking Services | CSR Manager | 78 m | Islamabad, Pakistan | UAE |

| H | Software Solutions | Marketing Manager | 110 m | Lahore, Pakistan | US |

| I | International retail | Marketing Manger | 80 m | Lahore, Pakistan | UAE |

| J | Auto/Car manufacturer and distributor | CSR Manager | 98 m | Lahore, Pakistan | Japan |

| CSR Domains | Empirical Focus |

|---|---|

| Philanthropic/Discretionary | All MNC managers explicitly motioned voluntary action or philanthropic activities. |

| Ethical | Most of the MNC managers (B, E, F, and J) mentioned the ethical dimension of responsibility. |

| Legal | Not a single respondent mentioned the legal dimension of responsibility. |

| Economic | Only one respondent focused on net profit and revenue (Company H). |

| Principles of Motivation | Empirical Focus |

|---|---|

| Legitimacy | Giving back to the society (Companies B, E D, F, J) |

| Meeting interests and needs of societal expectations (Company A.I) | |

| Acceptance in the local community (Company C) | |

| Accountability to society (Company G) | |

| Managerial discretion | Explicit positive interest and encouragement of CEO and senior management (Companies A, E, J) |

| Implicit negative discretion (Companies H, B) | |

| Public responsibility | Core business value (Company D, I) |

| CSR linked with primary or secondary operations (companies E, F) |

| Wood’s (1991) perspective | Environmental Scanning process: Generally MNCs are not involved in systematic environmental scanning process (Companies A, B, C, E, F, H, I, J) |

| Stakeholder Management: Mixed views (Companies E, C, I, J), mostly engagement is at an operational level, not systematic and continuous. Mistrust of stakeholders (Companies C, D, E) | |

| Issue Management: Often on an ad hoc basis | |

| Carroll (1979) Responsiveness | No evidence of proactive responsiveness strategy |

| All MNCs are involved in reactive and defensive strategy to maintain legitimacy |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yunis, M.S.; Jamali, D.; Hashim, H. Corporate Social Responsibility of Foreign Multinationals in a Developing Country Context: Insights from Pakistan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103511

Yunis MS, Jamali D, Hashim H. Corporate Social Responsibility of Foreign Multinationals in a Developing Country Context: Insights from Pakistan. Sustainability. 2018; 10(10):3511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103511

Chicago/Turabian StyleYunis, Mohammad Sohail, Dima Jamali, and Hina Hashim. 2018. "Corporate Social Responsibility of Foreign Multinationals in a Developing Country Context: Insights from Pakistan" Sustainability 10, no. 10: 3511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103511