Abstract

Generative AI (GenAI) now produces text, images, audio, and video that can be perceptually convincing at scale and at negligible marginal cost. While public debate often frames the associated harms as “deepfakes” or incremental extensions of misinformation and fraud, this view misses a broader socio-technical shift: GenAI enables synthetic realities—coherent, interactive, and potentially personalized information environments in which content, identity, and social interaction are jointly manufactured and mutually reinforcing. We argue that the most consequential risk is not merely the production of isolated synthetic artifacts, but the progressive erosion of shared epistemic ground and institutional verification practices as synthetic content, synthetic identity, and synthetic interaction become easy to generate and hard to audit. This paper (i) formalizes synthetic reality as a layered stack (content, identity, interaction, institutions), (ii) expands a taxonomy of GenAI harms spanning personal, economic, informational, and socio-technical risks, (iii) articulates the qualitative shifts introduced by GenAI (cost collapse, throughput, customization, micro-segmentation, provenance gaps, and trust erosion), and (iv) synthesizes recent risk realizations (2023–2025) into a compact case bank illustrating how these mechanisms manifest in fraud, elections, harassment, documentation, and supply-chain compromise. We then propose a mitigation stack that treats provenance infrastructure, platform governance, institutional workflow redesign, and public resilience as complementary rather than substitutable, and outline a research agenda focused on measuring epistemic security. We conclude with the Generative AI Paradox: as synthetic media becomes ubiquitous, societies may rationally discount digital evidence altogether, raising the cost of truth for everyday life and for democratic and economic institutions.

1. Introduction

Generative AI (GenAI) technologies possess unprecedented potential to reshape our world and our perception of reality. These technologies can amplify traditionally human-centered capabilities, such as creativity and complex problem-solving in socio-technical contexts [1]. By fostering human–AI collaboration, GenAI could enhance productivity, dismantle communication barriers across abilities and cultures, and drive innovation on a global scale [2].

Yet, experts and the public are deeply divided on the implications of GenAI. On one hand, proponents emphasize its transformative benefits across education, healthcare, accessibility, and creative labor; on the other hand, critics warn that the same generative capabilities can be weaponized for disinformation, fraud, harassment, and manipulation at societal scale. As with past technological upheavals, the core issue is not that harms are new, but that the cost, speed, personalization, and reach of harmful acts may change the equilibrium between trust and deception.

This paper highlights a subtler, yet potentially more perilous risk: GenAI systems may enable personalized synthetic realities (bespoke representations of the world tailored to match an individual’s preferences, vulnerabilities, and priors) and thus fundamentally alter the fabric of shared reality. When persuasive synthetic content is embedded in interactive systems (chatbots, personalized feeds, multi-agent simulacra), individuals may not merely consume falsehoods; they may inhabit coherent, emotionally resonant, and socially reinforced narratives that are difficult to falsify from within. The long-run danger is a society in which (i) shared evidence is scarce, (ii) institutions face escalating verification costs, and (iii) disagreement becomes epistemically irresolvable because each side can point to “credible” synthetic documentation of incompatible worlds.

To make this shift concrete, Figure 1 illustrates three complementary facets of the problem: (i) synthetic identity (a proof-of-concept workflow for generating “proofs of identity”), (ii) synthetic content depicting never-occurred events, and (iii) the possibility of embedded or subliminal steering cues in generated imagery. Together, these examples motivate the central claim of this paper: GenAI risk is not limited to isolated fake artifacts, but extends to coherent, interactive, and personalized synthetic realities that can erode the epistemic foundations of everyday life and institutions.

Figure 1.

(Top Left) In January 2024, the r/StableDiffusion community on Reddit demonstrated a proof-of-concept workflow to synthetically generate personas and (Bottom Left) proofs of identity. (Top Right) GenAI can produce lifelike depictions of never-occurred disaster events to exploit public sympathy, such as the viral “Girl with Puppy” deepfakes circulated during Hurricane Helene (2024) [3], and even (Bottom Right) subliminal messages in generated content (optical illusion reads OBEY).

Yet, this technological capability engenders a systemic irony. We term this the Generative AI Paradox: the very technology designed to maximize the fidelity and production of information may ultimately lead to a “post-veridical” state where the abundance of information destroys the utility of the information medium itself. By making digital content “perfectly believable,” we risk rendering it “perfectly unbelievable.”

The paradox lies not merely in the existence of deception, but in a market failure of the “truth economy”: as GenAI drives the cost of generating high-fidelity evidence (documents, voices, photos) toward zero, it forces the societal cost of verifying that evidence toward infinity.

1.1. Contributions and Scope

This article offers four contributions. First, it clarifies the concept of synthetic reality as a layered stack (content, identity, interaction, institutions). Second, it expands a taxonomy of GenAI risks and harms, emphasizing pathways by which synthetic media becomes a systemic epistemic vulnerability. Third, it explains what changes qualitatively with GenAI compared to earlier deception technologies (e.g., Photoshop) and connects these shifts to contemporary risk realizations. Fourth, it proposes a mitigation stack and a research agenda oriented around measurement, provenance, and institutional redesign.

1.2. A Taxonomy of GenAI Risks and Harms

At the heart of these concerns is a taxonomy of GenAI risks and harms recently proposed in [4]. The taxonomy identifies common misuse vectors (e.g., propaganda, deception) and maps them to the harms they can produce.

- Personal loss

This category encompasses harms to individuals, including non-consensual synthetic imagery, impersonation, targeted harassment, defamation, privacy breaches, and psychological distress. GenAI can amplify these harms by (i) lowering the skill barrier to produce convincing personal attacks, (ii) increasing the speed at which attackers can iterate on content, and (iii) enabling persistent personalization (e.g., adversaries generating content calibrated to a target’s identity, relationships, and triggers). Beyond acute episodes, repeated exposure to realistic fabrications can induce chronic distrust, social withdrawal, and a “reality fatigue” in which individuals disengage from civic and informational life [5,6].

- Financial and economic damage

GenAI intensifies economic threats by scaling classic fraud and by enabling higher-conviction deception (e.g., realistic voice/video impersonation in high-stakes transactions). It also introduces new costs: firms must invest in verification, compliance, provenance, and incident response; newsrooms must authenticate content under tighter timelines; and everyday transactions accrue friction as digital evidence loses default credibility. These effects create an “epistemic tax” on commerce and governance [7].

- Information manipulation

GenAI can construct false but convincing narratives, fabricate evidence, and flood information channels with plausible content, thereby overwhelming attention and editorial capacity [8]. Crucially, manipulation is no longer limited to producing artifacts; it can be delivered through interactive persuasion, where systems adapt in real time to a person’s beliefs and emotional state. This shifts information integrity threats from “content authenticity” to “belief formation security,” raising concerns about public discourse, journalism, and democratic deliberation.

- Socio-technical and infrastructural risks

Finally, GenAI can destabilize socio-technical systems by eroding trust in institutions and by enabling coordinated influence operations that exploit platform affordances at scale. These harms include institutional delegitimation, polarization, and governance paralysis, as well as technical risks such as model supply-chain compromise (poisoning, backdoors), unsafe deployment, and the misuse of generative tools in critical workflows. At the extreme, synthetic reality can become a tool of authoritarian control: a capacity to manufacture documentation, testimony, and “public consensus” at will.

- Epistemic and institutional integrity

We propose making epistemic integrity explicit as a cross-cutting harm category. When synthetic content becomes ubiquitous and verification is costly, societies may drift toward one of two failure modes: (i) credulity (believing convincing fabrications) or (ii) cynicism (believing nothing, including true evidence). Both outcomes undermine accountability and empower strategic actors who can exploit confusion, delay, or plausible deniability. This dimension connects the taxonomy to institutional design: courts, elections, journalism, and finance rely on evidence regimes that assume a baseline level of authenticity and auditability.

2. From Synthetic Media to Synthetic Reality

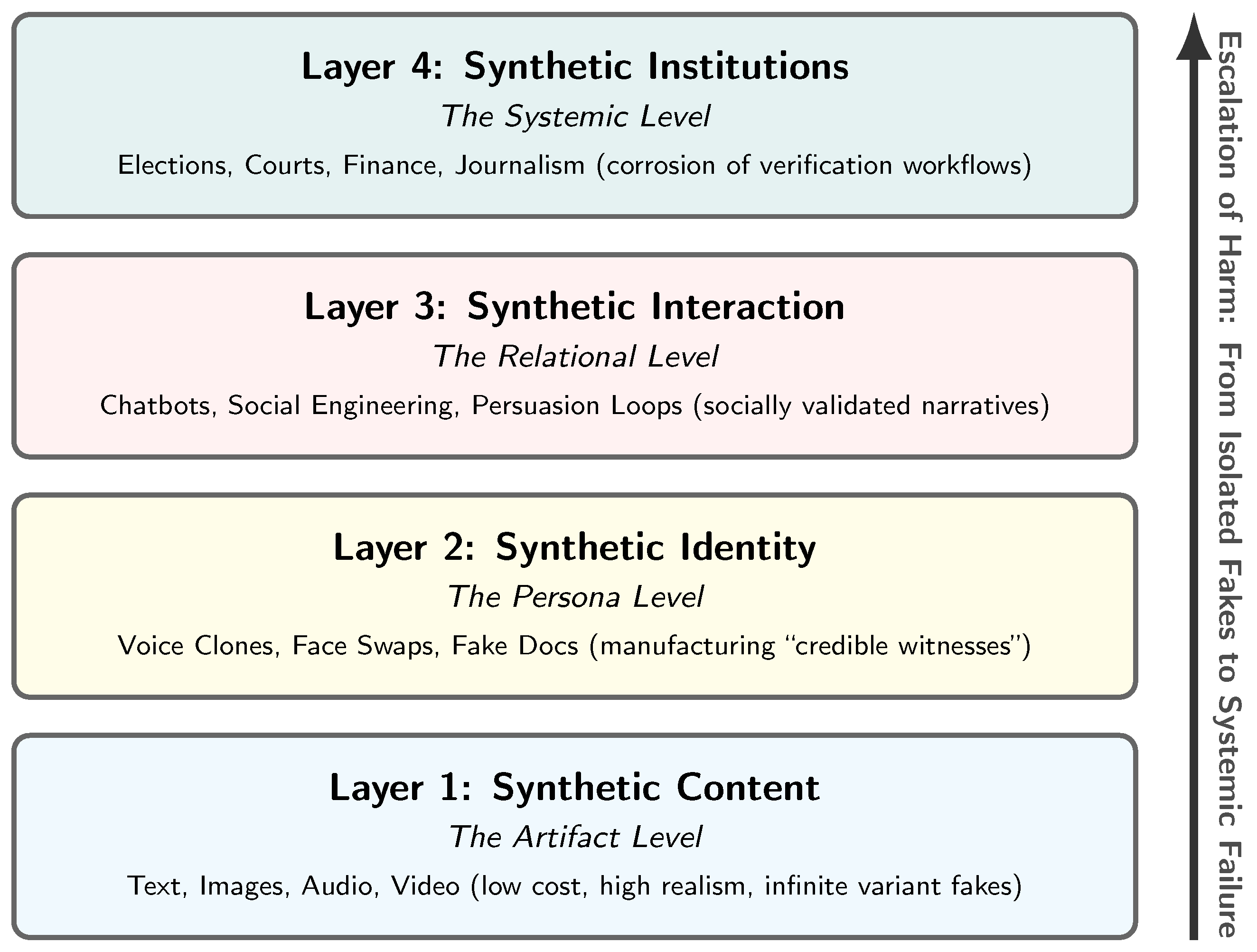

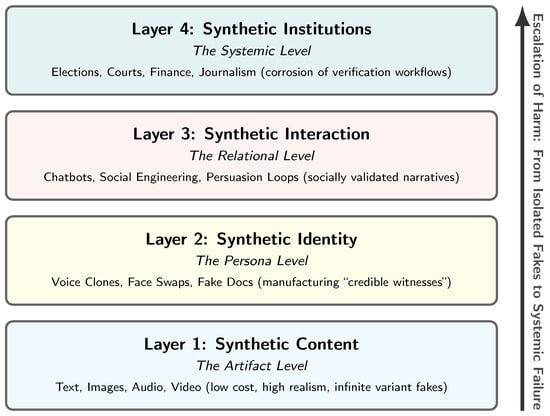

Discussions of GenAI risk often center on synthetic media: outputs that imitate human-produced artifacts (text, images, audio, video). We argue that the more consequential shift is toward synthetic reality: a coherent environment in which artifacts, identities, and interactions are partially machine-generated and mutually reinforcing, such that they can be experienced as credible from within. In other words, the core risk is not only that individual items of content can be forged, but that entire contexts of belief can be manufactured: who is present, what evidence exists, which claims circulate, and how they are socially validated. As shown in Figure 2, we therefore define synthetic reality as a layered stack (content, identity, interaction, institutions) that maps naturally onto distinct attack surfaces and defensive levers.

Figure 2.

Synthetic reality as a layered stack. Generative systems first produce synthetic content (text, image, audio, video), which enables synthetic identity (impersonation/persona fabrication) and synthetic interaction (adaptive, socially present dialogue). These layers can mutually reinforce one another, amplifying credibility and persuasion, while shifting verification burdens onto institutions (e.g., journalism, courts, elections, finance) as high-conviction artifacts become cheap and abundant.

2.1. Layer 1: Synthetic Content (The Artifact Level)

This layer includes generated or edited text, images, audio, and video. Its salient properties are high realism, rapid production, and low marginal cost, including iterative variation (many plausible alternatives) and compositional editing (the ability to target and alter specific details while preserving global plausibility). Alone, this layer supports familiar harms (forgery, defamation, propaganda), but it becomes far more potent when coupled with identity and interaction. Figure 1 (top right) illustrates this baseline capability: the cheap generation of credible-looking depictions of disaster events that never occurred. For example, during Hurricane Helene in 2024, synthetic images of a stranded child holding a puppy went viral, successfully soliciting emotional engagement and donations before being debunked [3]. More subtly, synthetic content can be optimized not only to depict falsehoods but also to steer attention and interpretation (Figure 1, bottom right), blurring the line between persuasion and perception.

2.2. Layer 2: Synthetic Identity (The Persona Level)

Synthetic reality expands when adversaries can convincingly represent specific people rather than merely generating content. We term this the Persona Level, not to imply autonomous general intelligence, but to describe the capability to simulate a coherent agent (i.e., an entity with a consistent history, voice, and identity) that persists across interactions. As illustrated in Figure 1 (left), GenAI can fabricate identity-linked artifacts (voice clones, facial reenactment) and supporting “evidence” (fake documentation) to manufacture ”credible witnesses.” This layer is distinct from simple content generation because it binds artifacts to a specific persona. The risk is that identity signals which once served as high-friction proof (a voice match, a consistent face, a document trail) become cheap to manufacture. When a synthetic agent can maintain a consistent persona across time and platforms, it bypasses the “stranger danger” heuristic, allowing adversaries to infiltrate trust-based workflows (e.g., onboarding, authorization, and interpersonal relationships).

2.3. Layer 3: Synthetic Interaction (The Relational Level)

Interactive systems can simulate dialogue and social presence. This enables persuasion that adapts to the target, generates social proof, and sustains long-running manipulative relationships (e.g., romance scams, radicalization pathways, coercive harassment). Synthetic interaction matters because belief formation is not a passive function of artifacts; it is shaped by conversation, feedback, and social reinforcement. Compared to static misinformation, interactive agents can (i) probe uncertainty, (ii) personalize arguments and emotional framing, and (iii) escalate commitment over time. In this sense, synthetic interaction operationalizes synthetic content and identity into lived experience, turning isolated artifacts into coherent narratives that can feel socially and emotionally validated.

2.4. Layer 4: Synthetic Institutions (The Systemic Level)

At the institutional layer, synthetic content and identity interfere with processes that depend on evidence and provenance: elections (campaign messaging and voter outreach), courts (evidence authenticity and witness credibility), finance (authorization and fraud), and journalism (verification under time pressure). The core issue is that many institutional workflows were optimized for a world in which certain proofs were costly to fabricate and therefore informative. Synthetic reality weakens this assumption by making high-conviction artifacts cheap and abundant. Concretely, it stresses verification regimes that rely on (i) perceptual cues as authentication (“I recognize the voice/face”), (ii) documentation as scarce evidence (“the paperwork looks real”), (iii) attention as the binding constraint (“a human can review the important items”), and (iv) shared exposure for correction (“if it is false, the rebuttal will reach the same audience”). Synthetic reality is therefore not merely a media problem but an institutional resilience problem.

Taken together, these layers clarify why synthetic reality is best treated as a systems risk: content realism is only the entry point; identity and interaction provide credibility and momentum; and institutions bear the externalities when verification must be performed under time pressure and adversarial adaptation. In the next section, we detail the qualitative shifts GenAI introduces (cost collapse, scale, personalization, provenance gaps, and trust erosion) that make this stack operationally consequential.

3. What You Can’t Tell Apart Can Harm You: Why GenAI Changes the Game

One might argue that the harms in our taxonomy are not uniquely enabled by GenAI; fraud, propaganda, and defamation long predate modern AI. The key shift is not the existence of deception, but the way GenAI changes its economics and operational feasibility. When synthetic content, synthetic identity, and synthetic interaction become cheap, fast, and scalable, the balance between trust and verification changes for individuals, platforms, and institutions. We group these shifts into seven mechanisms that jointly explain why synthetic reality is an elevated socio-technical risk rather than “more of the same” misinformation.

3.1. Cost Collapse and Commoditization

GenAI lowers the barriers to creating realistic content and identity artifacts. What previously required specialized skills (video editing, graphic design, voice acting, or sophisticated social engineering) can now be produced via prompts, templates, and turnkey services. This cost collapse expands the pool of capable adversaries, reduces the time between intent and execution, and enables rapid experimentation: attackers can iterate until an output “looks right” for a target audience. The resulting threat landscape resembles a commoditized service ecosystem rather than isolated bespoke attacks.

3.2. Scale and Throughput

GenAI supports rapid iteration and mass production. Adversaries can generate thousands of variants of a message, image, or persona and A/B test them for engagement, credibility, or emotional impact. This shifts the defensive problem from identifying a small number of fakes to managing a high-volume stream of plausible variations, often delivered across multiple platforms and accounts by coordinated networks to systematically promote partisan narratives or amplify low-credibility content [9,10]. Throughput also facilitates “flooding” strategies, where the sheer abundance of synthetic content overwhelms attention, moderation capacity, and journalistic verification under time pressure [11,12].

3.3. Customization for Malicious Use

Open model ecosystems, fine-tuning, and retrieval-augmented generation enable domain-specific deception. Content can be made to mimic the style of a specific institution, community, or individual; scams can mirror internal workflows; and persuasive narratives can be localized to cultural context and current events. The risk is not only realism but fit: deception becomes more effective when it matches the target’s language, norms, and expectations, reducing the cues that would otherwise trigger skepticism.

3.4. Hyper-Targeted Persuasion and Micro-Segmentation

GenAI enables influence campaigns that are personalized at scale. Instead of broadcasting one narrative to millions, adversaries can craft many narratives for small segments, each optimized to exploit distinct fears, identities, or grievances. Micro-segmentation undermines collective rebuttal: communities may not even see the same claims, and corrections may not reach the audiences most affected. Over time, this can amplify polarization by nudging different groups into incompatible interpretive frames, each supported by seemingly credible synthetic “evidence” and tailored messaging.

3.5. Synthetic Interaction and the Automation of Social Engineering

Classic social engineering is labor-intensive. With GenAI, interaction itself can be automated [13]. Conversational agents can build rapport, probe uncertainty, adapt tone, and guide victims through multi-step fraud; they can also sustain longer-running manipulative relationships, blending emotional support, selective evidence, and escalating commitment over time. This transforms deception from a static content problem into an interactive process problem: belief formation and decision-making can be influenced through dialogue, feedback loops, and simulated social presence.

3.6. Detection Limits, Watermarking Fragility, and the Provenance Gap

Detection of GenAI outputs remains imperfect, especially under compression, re-encoding, adversarial perturbations, and cross-model remixing. Watermarking can help in controlled pipelines, but in open ecosystems it may be removed, weakened, or bypassed, and it does not address unauthenticated media generated outside watermarking regimes. The deeper issue is a provenance gap: even if some fakes are detectable, institutions need reliable chains of custody and standards for authenticated media. In practice, high-stakes decisions require more than probabilistic classifiers; they require auditable provenance signals and process-level safeguards.

3.7. Trust Erosion and Plausible Deniability

As synthetic outputs become widespread, societies face an additional failure mode: authentic evidence can be dismissed as fake. This dynamic increases the payoff to strategic denial and delay, allowing actors to exploit uncertainty even when allegations are true. The result is epistemic instability: disputes become harder to resolve because the evidentiary substrate itself is contested, and audiences can rationally default to suspicion. In aggregate, this produces an “epistemic tax”: more friction and cost are required to establish what happened, who said what, and which sources are trustworthy.

3.8. Synthesis: Fueling the Paradox

These seven mechanisms collectively accelerate the Generative AI Paradox. When Cost Collapse and Scale make high-fidelity artifacts abundant, they flood the marketplace of ideas with “perfectly believable” signals. This triggers the Trust Erosion that characterizes the paradox: society is forced to discount digital evidence not because it looks fake, but because it looks too real to be trusted without costly verification. The mechanisms described above are therefore not just features of the technology; they are the drivers of this epistemic inflation.

4. How Risks Materialize: Representative Risk Realizations

To ground the taxonomy in recent developments, we compile a compact “case bank” (Table 1) that illustrates how synthetic reality risks have already materialized in operational settings. The goal is not exhaustive coverage but mechanism diversity: we select cases that (i) are documented by high-quality public reporting and/or primary sources, (ii) span distinct harm domains (fraud, elections, harassment, documentation, and supply-chain compromise), and (iii) exhibit a clear linkage to one or more layers of the synthetic reality stack (content, identity, interaction, institutions). We also note an important limitation: public documentation is uneven across regions and sectors (many incidents are privately handled or under-reported), so the cases below should be interpreted as illustrative lower bounds rather than a complete census of harms.

Table 1.

Case bank of representative GenAI “synthetic reality” risk realizations (2023–2025), organized by dominant mechanisms and harm pathways.

4.1. Representative Risk Realizations (2023–2025)

Table 1 summarizes the mechanisms and harm pathways; here we briefly narrate each case to emphasize that these are not hypothetical failure modes, but observed events whose common structure is the same: GenAI reduces the cost of producing high-conviction artifacts, and then exploits social and institutional workflows that were designed for a world where such artifacts were expensive to fabricate.

- Case Category A: High-conviction impersonation fraud in enterprise workflows.

In early 2024, Hong Kong police described a fraud case in which an employee was drawn into what appeared to be a confidential video meeting with senior colleagues and subsequently authorized large transfers to multiple accounts. The reported modus operandi combined a phishing pretext with a fabricated group video conference assembled from publicly available video and voice materials; once the victim accepted the meeting as authentic, the attackers shifted into familiar operational routines (follow-up instructions, approvals, and transfers) that converted perceived legitimacy into immediate financial action. Public reporting later identified the victim organization and the approximate scale of losses, underscoring that even a single high-conviction “meeting” can defeat standard internal controls when verification is implicitly delegated to the perceived authenticity of face/voice cues [14,15,16]. (See Table 1, Case Category A, for the mechanism summary).

- Case Category B: Election-adjacent synthetic outreach and voter manipulation.

A parallel pattern appears in election contexts: synthetic outreach leverages the credibility of familiar voices and institutional cues to create confusion at scale. In the New Hampshire primary context, widely reported AI-generated robocalls mimicked a well-known political figure’s voice and delivered demobilizing messaging timed to the electoral calendar. The subsequent enforcement actions illustrate a key institutional shift: the response targeted not only the content [34], but also the communications infrastructure that carried it (e.g., provider-level compliance, blocking, and penalties). This case is representative of how GenAI turns “who said it” into a programmable variable, enabling low-cost, targeted influence attempts whose corrections are often slower and less visible than initial exposure [17,18,19]. (See Table 1, Case Category B).

- Case Category C: Non-consensual synthetic sexual imagery as platform-amplified, persistent harassment.

Synthetic reality risk is not limited to fraud and politics; it also manifests as scalable, identity-targeted harassment. In early 2024, sexually explicit AI-generated deepfakes of a high-profile public figure spread across major platforms rapidly enough that at least one platform implemented temporary search restrictions to slow discovery and resharing. The episode illustrates two durable properties of this harm class: (i) the victim’s identity becomes a reusable asset for abuse (faces and likenesses are easily recontextualized), and (ii) platform responses often occur after wide exposure, while copies, derivatives, and reuploads keep the abuse persistent. Policy responses in the United States (including federal notice-and-removal provisions for covered platforms) further indicate that non-consensual synthetic intimate imagery is now treated as a mainstream online safety threat rather than an edge case [20,21,22,23]. (See Table 1, Case Category C).

- Case Category D: Fabricated documentation and the corrosion of routine verification.

A more diffuse but structurally important development is the rise of plausible “everyday documents” that defeat quick human inspection: receipts, invoices, screenshots, emails, and other paperwork that function as substrates of routine trust. Reporting from 2025 describes a measurable increase in AI-generated fake receipts and related expense fraud, where realism (logos, typography, wear patterns, itemization) plus metadata manipulation makes visual review unreliable. Industry responses increasingly treat this as an operational shift rather than an anomaly: the defense moves from human spot-checks to automated detection, metadata forensics, and cross-validation against contextual constraints. The systemic risk is that as forged documentation becomes cheap and abundant, institutions drift toward default suspicion, increasing friction and error costs for legitimate participants while simultaneously creating cover for strategic denial (“that proof could be fake”) [24,25,26,27,28]. (See Table 1, Case Category D).

- Case Category E: Compromised generative pipelines and model supply-chain risk.

Synthetic reality can also be shaped upstream, at the level of model artifacts and generation infrastructure. Security reporting in 2025 documented malicious ML model uploads to a major model-sharing hub, designed to execute malware when loaded; a classic supply-chain pattern, now expressed through the distribution of “models as files” [31]. Related advisories highlight how scanner assumptions can be bypassed, allowing embedded payloads to evade safeguards while remaining loadable by standard tooling [30]. At a different layer, technical work on backdoors and data poisoning demonstrates that harmful behaviors can be deliberately implanted and may persist through common training or alignment procedures, creating a risk that downstream users experience as “the system” rather than an obvious attack [32,33]. Together, these examples motivate treating GenAI as an end-to-end socio-technical pipeline whose integrity depends on provenance, robust scanning, safe-loading defaults, and continuous monitoring, not just on model capability or content filters [29]. (See Table 1, Case Category E).

4.2. Cross-Case Synthesis

Across the cases in Table 1, the common thread is not merely the presence of fake artifacts; it is the emergence of credible alternative contexts constructed through the content + identity + interaction + institution paradigm. Each event follows a recurring operational pattern: (1) a high-conviction artifact (a call, a clip, a document, a persona, a model file) is produced cheaply; (2) it is inserted at a workflow “choke point” where humans routinely rely on trust cues; (3) automation and scale increase exposure or repetition; (4) correction lags behind initial impact; and (5) institutions absorb externalities as verification load, friction, and contested evidence. This synthesis motivates the mitigation framing in the next section: reducing harm requires layered interventions that harden workflows and provenance, not only better detection of individual fakes.

4.3. Structural Analysis of Threat Vectors

Table 2 moves beyond the narrative of these incidents to isolate the specific structural mechanisms that enable them. By decomposing these events into GenAI Modality, Distribution Vector, and Exploited Vulnerability, a consistent pattern emerges: attackers are not simply generating “fake content,” they are engaging in epistemic arbitrage: exploiting the latency between high-speed generation and low-speed verification.

Table 2.

Threat Vector Analysis of GenAI Incidents (2023–2025). This analysis decomposes high-profile incidents as structural exploitations of specific vulnerabilities via distinct GenAI modalities.

4.3.1. Algorithmic vs. Institutional Latency

The Financial Market Destabilization case (cf., Table 2) highlights a temporal vulnerability. The attack succeeded because the Distribution Vector (verified bot networks) and the victim reaction (algorithmic trading bots) operated at millisecond speeds, whereas the verification mechanism (official Pentagon denial) operated at human bureaucratic speeds. This “verification gap” creates a window of opportunity where synthetic narratives can move markets or public opinion before the “truth” has time to put on its boots.

4.3.2. The Compression of Social Proof

A critical insight from the Corporate Identity Theft case (cf., Table 2) is the weaponization of “quorum trust.” Traditional fraud detection relies on the heuristic that coordinating multiple accomplices is resource-intensive and high-risk. The deepfake video conference scam dismantled this heuristic by allowing a single attacker to simulate a “quorum” of trusted colleagues simultaneously. The vulnerability here was not merely the visual quality of the faces, but the authority bias triggered by the perceived consensus of the group. GenAI collapses the cost of manufacturing social proof to near zero.

4.3.3. Parasocial Exploitation

In the Electoral Interference case (cf., Table 2), the threat vector shifted from informational to relational. By cloning a trusted political voice, the attack exploited parasocial interaction, i.e., the psychological bond voters feel with public figures [17,18]. Unlike text-based misinformation, audio deepfakes bypass analytical filtering and trigger emotional recognition, suggesting that auditory synthesis poses a distinct class of risk to democratic deliberation that requires specific mitigation strategies beyond fact-checking.

4.3.4. The Failure of Static Verification

Finally, the theoretical case of Synthetic Document Forgery (cf., Table 2) illustrates the fragility of bureaucratic trust. Most ”Know Your Business” (KYB) and compliance workflows are designed to verify the existence of a document (e.g., “does this invoice look like a standard template?”), not its provenance [24,25]. Multimodal LLMs can now generate documents that are perfectly compliant with static visual standards but structurally fabricated. This indicates that the “document” can no longer serve as a self-contained unit of trust; verification must shift from inspecting the artifact to cryptographically verifying its origin.

- Synthesis: As Table 2 demonstrates, the common thread across these vectors is the exploitation of human and institutional reliance on “proxy signals” for truth (a familiar voice, a blue checkmark, a standard invoice). GenAI allows adversaries to manufacture these proxies cheaply, necessitating the shift to the Mitigation Stack proposed next.

5. Mitigation as a Stack (Not a Silver Bullet)

The preceding analysis suggests that the Generative AI Paradox cannot be solved by simply detecting fakes; it must be resolved by re-introducing value to the “truth economy.” If the paradox is driven by the costless production of believable signals, then mitigation requires re-pricing those signals. The stack proposed below aims to impose necessary friction on deception while creating “fast lanes” for truth. Provenance infrastructure reduces the cost of verifying authenticity, while Institutional Redesign accepts that the baseline cost of forgery has dropped. We treat these layers as complementary efforts to stabilize the epistemic market.

5.1. Provenance and Content Authenticity Infrastructure

Provenance systems (e.g., cryptographic signing, secure capture, and content credentials) aim to establish chain-of-custody for media and to communicate authenticity signals to downstream users. Their value is greatest when adopted end-to-end by high-stakes institutions (newsrooms, election offices, courts, public agencies) and integrated into common consumer interfaces, so that authentication becomes routine rather than exceptional. However, provenance is not universal: it does not help when content is generated outside authenticated pipelines, when devices are compromised at capture time, when metadata is stripped in transit, or when audiences lack accessible verification tools. Provenance should therefore be treated as infrastructure that improves auditability and reduces ambiguity for authenticated media, not as a guarantee that fakes disappear.

A practical implication is asymmetric: provenance can meaningfully raise confidence in verified content even if it cannot label all unverified content. This suggests prioritizing provenance for categories where authenticity is most consequential (official announcements, high-reach news, election information, evidentiary media, financial authorization), while acknowledging that the unauthenticated “background” of the internet will remain noisy.

5.2. Platform Governance and Friction for Virality

Platforms can reduce harm by shaping exposure and incentives. Interventions include (i) limiting algorithmic amplification of unverified media during high-risk periods (elections, breaking news, crises), since recommendation algorithms can disproportionately amplify partisan content and skew political exposure [35]; (ii) prominently surfacing provenance and uncertainty signals [36]; (iii) rate-limiting newly created accounts and coordinated inauthentic behavior [37]; and (iv) providing rapid response channels for victims of impersonation and harassment [38]. Importantly, governance must anticipate adversarial adaptation: policies are targets, and enforcement must be iterative and evidence-driven.

In the synthetic reality regime, “friction” becomes a legitimate safety tool. Small increases in effort, such as additional verification steps for high-velocity sharing, temporary distribution throttles for suspicious bursts, or delayed virality for unprovenanced media, can meaningfully reduce harm without requiring perfect classification of real/fake content.

5.3. Institutional Process Redesign Under Cheap Forgery

Institutions should redesign workflows around the assumption that synthetic identity and fabricated evidence are cheap. This includes: out-of-band verification for high-value transfers; multi-factor approval protocols that do not rely on voice/face cues; authenticated channels for official communications; and evidentiary standards that incorporate provenance metadata and chain-of-custody. More generally, institutions should shift from “artifact-based trust” (believing what looks authentic) to “process-based trust” (believing what is generated and transmitted through authenticated, auditable procedures).

This shift is also an equity issue: when verification burdens rise, those without access to privileged channels (legal counsel, specialized tools, verified identities) may be disproportionately harmed. Institutional redesign should therefore aim for accessible authentication pathways and clear escalation procedures for contested evidence.

5.4. Public Resilience and Epistemic Hygiene

Societies need norms and literacy that go beyond “spot the fake.” Individuals cannot be expected to personally authenticate everything they see, nor should the burden of proof be devolved entirely onto users. Public resilience should emphasize (i) calibrated skepticism in high-stakes contexts, (ii) reliance on authenticated channels for critical information, (iii) awareness of manipulation tactics (urgency, emotional triggers, social proof, impersonation), and (iv) community-level correction mechanisms that can propagate verified rebuttals into the same networks where synthetic claims spread.

A useful reframing is “epistemic hygiene”: habits that reduce exposure to manipulation and increase reliance on trustworthy processes, analogous to public health measures that reduce exposure to disease without requiring perfect individual diagnosis.

5.5. Policy and Accountability

Policy can clarify liability and incentives while protecting legitimate creative and assistive uses of GenAI. Interventions include disclosure requirements for synthetic political advertising and automated outreach, obligations for rapid response to impersonation and non-consensual intimate imagery, and minimum authentication standards in sensitive domains (e.g., election administration communications, high-value financial authorizations). The objective is not censorship but accountability: making it costly to deploy synthetic reality attacks, increasing the probability of attribution and sanction, and reducing the payoffs to ambiguity and denial.

5.6. A Synthesis: Mapping Mitigations to the Synthetic Reality Stack

Because synthetic reality operates as a stack, mitigations should be mapped to layers and failure modes. Provenance primarily strengthens the content and institution layers by enabling chain-of-custody; platform governance reduces amplification and coordinated abuse that intensify the interaction layer; institutional redesign hardens workflows against identity deception and forged documentation; and public resilience reduces susceptibility to persuasion loops. This mapping underscores why no single lever suffices: a system can fail at any layer, and adversaries will route around the strongest defenses. The realistic goal is therefore risk reduction through defense-in-depth, coupled with measurement and monitoring to detect where the stack is failing in practice.

5.7. Proposed Validation Framework

While the proposed Mitigation Stack is architectural in nature, its utility relies on rigorous empirical testing. We propose a three-tiered validation framework that outlines the necessary methodologies for future research to benchmark these defenses effectively.

5.7.1. Tier 1: Cross-Modal Consistency Benchmarking

Current benchmarks focus heavily on unimodal detection (e.g., detecting artifacts in images or text in isolation). To validate the proposed Detection Layer, future evaluation protocols must prioritize Cross-Modal Consistency.

- Methodology: Researchers should develop datasets that pair synthetic narratives with generated supporting evidence (e.g., a fake news article paired with a synthetic police report).

- Evaluation Goal: The validation must measure the system’s ability to detect semantic discordance between the narrative claims and the metadata or layout of the supporting documents, rather than just pixel-level or token-level artifacts.

5.7.2. Tier 2: Adversarial Red Teaming Simulations

Static datasets are insufficient against rapidly evolving GenAI models. To validate the Resilience Layer, we propose an Adversarial Red Teaming approach.

- Methodology: This involves a dynamic simulation where an “Attacker Agent” (using current State-of-the-Art generative models) attempts to bypass the mitigation stack using prompt engineering and multi-modal injection techniques.

- Evaluation Goal: The metric for success should not be simple detection accuracy, but rather the “Adaptation Rate”, e.g., measuring how quickly the mitigation stack requires updating to withstand a new vector of attack from the generative agent.

5.7.3. Tier 3: Friction and Viability Analysis

A theoretical mitigation is practically void if it breaks the user experience or introduces prohibitive latency. The Provenance Layer must be validated through Viability Analysis.

- Methodology: Deployment simulations that measure the computational overhead of cryptographic signing and verification processes at scale.

- Evaluation Goal: Validating that the time-to-verification remains within acceptable thresholds for real-time media consumption, ensuring that the security measures do not encourage user abandonment due to friction.

6. Open Problems and a Research Agenda

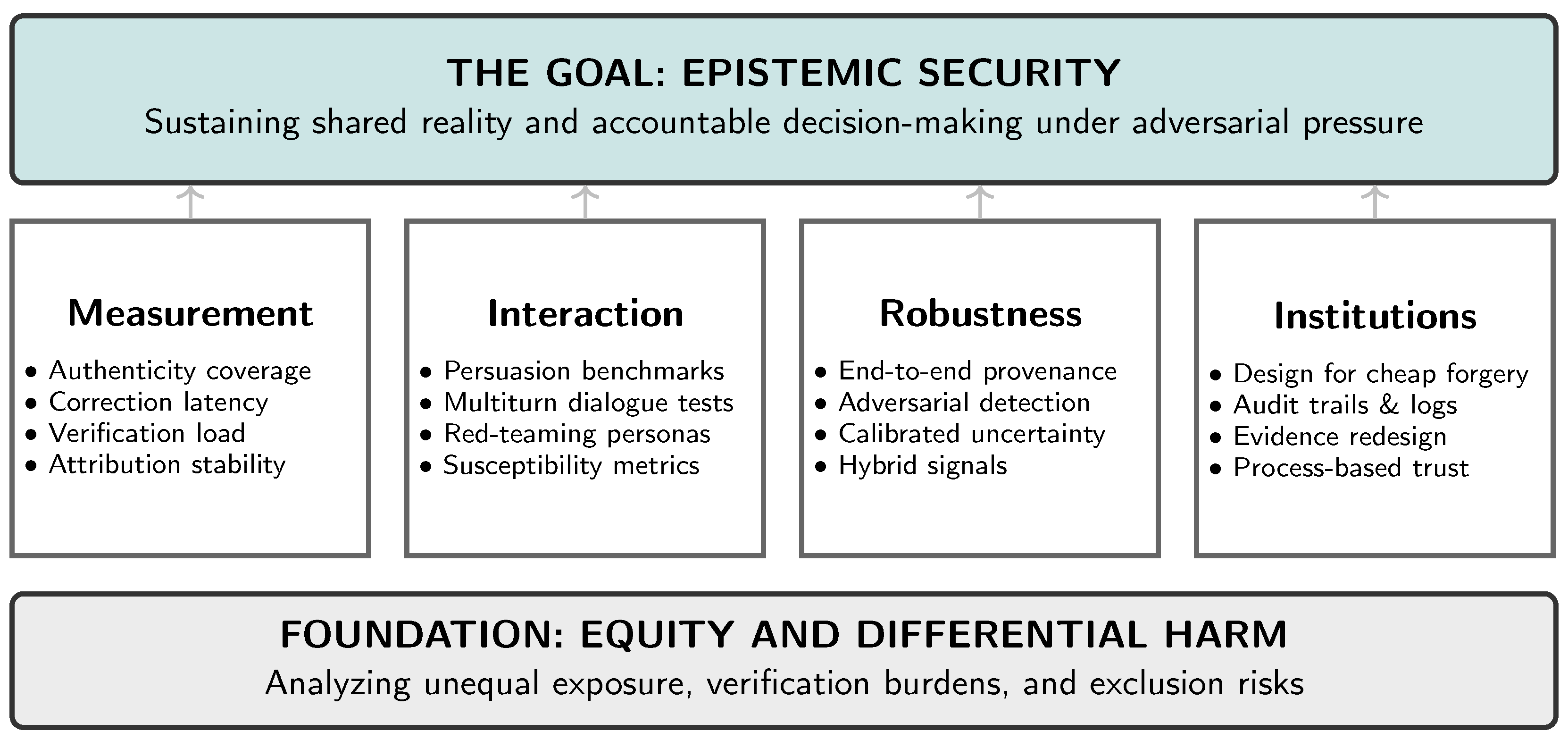

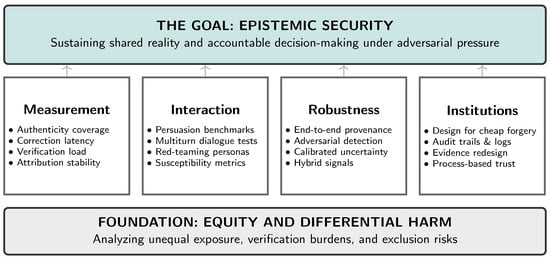

If synthetic reality is a systemic risk, then mitigation requires measurement. We cannot manage what we do not measure, and current information-integrity tooling is largely optimized for static artifacts rather than layered environments that combine content, identity, interaction, and institutional workflows. This section outlines a research agenda centered on operational metrics, benchmarks for interactive manipulation, robust provenance evaluation, and institutional design under cheap forgery. Figure 3 provides a scaffolding for researchers and practitioners to develop the scientific and engineering foundations for epistemic security: the capacity of socio-technical systems to sustain shared reality and accountable decision-making under adversarial pressure.

Figure 3.

A Research Agenda for Epistemic Security. Addressing synthetic reality risks requires a shift from measuring artifact authenticity to measuring systemic resilience. The agenda rests on four pillars: (1) operational metrics, (2) interactive benchmarks, (3) adversarial robustness, and (4) institutional redesign, all grounded in an analysis of equity and differential harm.

6.1. Measurement of Epistemic Security

We need operational metrics for how well a community, platform, or institution maintains shared reality under synthetic-reality conditions. Candidate constructs include: (i) authenticity coverage (the share of high-reach media carrying verifiable provenance); (ii) correction latency (time to converge on community-level consensus about authenticity, including the reach of verified rebuttals within affected networks); (iii) manipulation susceptibility (engagement, belief, or behavioral change under controlled synthetic interventions, with safeguards and ethical review); (iv) verification load (resources and friction required to authenticate claims, including false-positive burdens on legitimate actors); and (v) attribution stability (how reliably a system can trace content and claims to sources as adversaries adapt). Together, these measures can quantify the “epistemic tax” imposed by synthetic reality and identify where defensive investment yields the greatest marginal benefit.

6.2. Benchmarks for Interactive Manipulation

Most existing benchmarks focus on static model outputs. Synthetic reality requires benchmarks for interactive persuasion: multi-turn dialogue, adaptive targeting, relationship persistence, and the generation of social proof. We need experimental protocols that test how conversational agents can steer beliefs and decisions under realistic constraints, including: (i) bounded access to personal data, (ii) platform-like interaction limits, (iii) adversarial objectives (fraud, demobilization, harassment), and (iv) measurable outcome variables (e.g., changes in stated belief, willingness to share, compliance with a request). Because this research touches human susceptibility, it demands strong ethical safeguards, transparency, and oversight. One promising direction is controlled “red-team” evaluation using synthetic personas or consenting participants, combined with post-hoc auditing to identify the conversational strategies that drive harmful outcomes.

6.3. Adversarial Robustness of Provenance and Detection

Provenance systems must be evaluated as end-to-end socio-technical systems: not only cryptographic robustness, but usability, adoption incentives, failure modes, and attack surfaces (device compromise, metadata stripping, re-encoding, and cross-platform degradation). Detection should be treated as probabilistic evidence rather than as a binary oracle. This suggests three research priorities: (i) calibrated detectors with uncertainty reporting suitable for institutional decision-making; (ii) rigorous evaluation under realistic transformations and adversarial perturbations; and (iii) hybrid methods that combine weak content signals with stronger process signals (capture integrity, signing, transmission logs). Ultimately, the most valuable output is not “fake/not fake,” but decision-relevant confidence coupled with transparent provenance when available.

6.4. Institutional Design Under Cheap Forgery

Courts, elections, journalism, and finance will need redesigned evidence regimes. Research should identify which institutional assumptions break under cheap forgery and propose processes that remain robust when perceptual cues and documentation lose default credibility. Candidate directions include authenticated capture standards, verifiable logging and audit trails, standardized disclosure of uncertainty, and new legal or administrative procedures for contested synthetic evidence. A key challenge is balancing security with accessibility: verification processes that are too burdensome can exclude legitimate participation or entrench inequality, while lax processes invite manipulation.

6.5. Equity and Differential Harm

Synthetic reality harms will not be evenly distributed. Targets of harassment, marginalized communities, and those with less access to authenticated channels or legal recourse may bear disproportionate costs. These disparities are often exacerbated by the inherent biases in generative models themselves, which can reproduce and amplify societal stereotypes when deployed at scale [39]. Research must quantify differential exposure, differential verification burden, and downstream harms (economic, psychological, civic). Mitigation should be evaluated not only on overall error reduction, but also on whether it shifts burdens onto those least able to absorb them. This includes studying how provenance and verification tools are adopted across populations and whether “default suspicion” regimes amplify discrimination and exclusion.

6.6. A Unifying Agenda: From Artifact Authenticity to Epistemic Resilience

Across these problems, the unifying shift is from artifact authenticity to epistemic resilience. In a world where any single artifact can be forged, the central question becomes whether communities and institutions can reliably converge on what is true, assign responsibility, and act accountably. Achieving this will require interdisciplinary research spanning machine learning, security, HCI, computational social science, law, and public policy, coupled with empirical measurement in the wild. The core scientific challenge is to characterize, predict, and reduce the conditions under which synthetic reality produces persistent disagreement, institutional overload, and the erosion of shared ground.

7. Conclusions

GenAI magnifies familiar harms, but its bigger risk is the Generative AI Paradox. As we have argued, the capacity to manufacture credible contexts—identities, documents, and social proofs—at negligible cost threatens to decouple “believability” from “truth.”

The paradox creates a dangerous equilibrium: as synthetic media becomes ubiquitous, societies may rationally move toward discounting digital evidence altogether. This raises the cost of truth for democratic and economic institutions, empowering strategic actors who thrive on ambiguity. Addressing this requires more than better detection tools; it requires a structural commitment to Epistemic Security—building the technical and social infrastructure necessary to sustain shared reality when “seeing” is no longer “believing.”

The Generative AI Paradox is that as synthetic content becomes ubiquitous and increasingly difficult to distinguish, societies may rationally move toward discounting digital evidence altogether. This shift raises the cost of truth: verification becomes a privilege, institutional processes slow, and accountability erodes. It also empowers strategic actors through plausible deniability (i.e, authentic evidence can be dismissed as fake) and through attention flooding that delays correction and amplifies confusion.

This paradox yields observable pressures that can be measured and tested. We expect (i) increasing reliance on authenticated channels for critical information, (ii) longer correction latency and greater fragmentation of rebuttal reach under micro-segmentation, (iii) higher institutional verification load (time, personnel, compliance), and (iv) a rising incidence of strategic denial claims in high-salience events. These pressures together constitute an “epistemic tax” on governance, commerce, and civic life.

Addressing synthetic reality risk therefore requires defense-in-depth. Provenance infrastructure can raise confidence in authenticated media; platforms can add friction to virality and reduce coordinated abuse; institutions can redesign workflows around cheap forgery; and public resilience can shift norms from artifact-based trust to process-based trust. The research agenda we outline calls for metrics and benchmarks that move beyond static detection toward epistemic security: sustaining shared reality and accountable decision-making under adversarial pressure. The realistic goal is not perfect authenticity, but resilient verification regimes that preserve trust where it is most consequential.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to past and current members of the HUMANS lab at USC.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- California Government Operations Agency. State of California: Benefits and Risks of Generative Artificial Intelligence Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.govops.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2023/11/GenAI-EO-1-Report_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Eapen, T.T.; Finkenstadt, D.J.; Folk, J.; Venkataswamy, L. How Generative AI Can Augment Human Creativity. 2023. Available online: https://hbr.org/2023/07/how-generative-ai-can-augment-human-creativity (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- NPR. AI Images of Hurricanes and Other Disasters Are Flooding Social Media. 2024. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2024/10/18/nx-s1-5153741/ai-images-hurricanes-disasters-propaganda (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Ferrara, E. GenAI Against Humanity: Nefarious Applications of Generative Artificial Intelligence and Large Language Models. J. Comput. Soc. Sci. 2024, 7, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menczer, F.; Crandall, D.; Ahn, Y.Y.; Kapadia, A. Addressing the harms of AI-generated inauthentic content. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023, 5, 679–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, M.; Riemer, K.; Yuan, L.; Dennis, A.R. Beyond Deep Fakes. Commun. ACM 2023, 66, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurczyk, W.; Lee, D.; Vlachos, A. Disinformation 2.0 in the Age of AI: A Cybersecurity Perspective. Commun. ACM 2024, 67, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, E. Charting the landscape of nefarious uses of generative artificial intelligence for online election interference. First Monday 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minici, M.; Cinus, F.; Luceri, L.; Ferrara, E. Uncovering coordinated cross-platform information operations: Threatening the integrity of the 2024 U.S. presidential election. First Monday 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinus, F.; Minici, M.; Luceri, L.; Ferrara, E. Exposing cross-platform coordinated inauthentic activity in the run-up to the 2024 us election. In Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 28 April–2 May 2025; pp. 541–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augenstein, I.; Baldwin, T.; Cha, M.; Chakraborty, T.; Ciampaglia, G.L.; Corney, D.; DiResta, R.; Ferrara, E.; Hale, S.; Halevy, A.; et al. Factuality challenges in the era of large language models and opportunities for fact-checking. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2024, 6, 852–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augenstein, I.; Bakker, M.; Chakraborty, T.; Corney, D.; Ferrara, E.; Gurevych, I.; Hale, S.; Hovy, E.; Ji, H.; Larraz, I.; et al. Community Moderation and the New Epistemology of Fact Checking on Social Media. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.20067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, E. Social bot detection in the age of ChatGPT: Challenges and opportunities. First Monday 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. LCQ9: Combating Frauds Involving Deepfake. 2024. Available online: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202406/26/P2024062600192p.htm (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Financial Times. Arup Lost $25 mn in Hong Kong Deepfake Video Conference Scam. 2024. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/b977e8d4-664c-4ae4-8a8e-eb93bdf785ea (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- South China Morning Post. Hong Kong Employee Tricked into Paying out HK$4 Million After Video Call with Deepfake ‘CFO’ of UK Multinational Firm. 2024. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/law-and-crime/article/3263151/uk-multinational-arup-confirmed-victim-hk200-million-deepfake-scam-used-digital-version-cfo-dupe (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Federal Communications Commission. DA 24-102: Robocall Enforcement (Public Notice; Cease-and-Desist to Lingo Telecom Re: AI-Generated Voice). 2024. Available online: https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DA-24-102A1.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Associated Press. AI-Generated Voices in Robocalls Can Deceive Voters. The FCC Just Made Them Illegal. 2024. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/a8292b1371b3764916461f60660b93e6 (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- NPR. A Political Consultant Faces Charges and Fines for Biden Deepfake Robocalls. 2024. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2024/05/23/nx-s1-4977582/fcc-ai-deepfake-robocall-biden-new-hampshire-political-operative (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Associated Press. X Restores Taylor Swift Searches After Deepfake Explicit Images Triggered Temporary Block. 2024. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/adec3135afb1c6e5363c4e5dea1b7a72 (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- WIRED. GitHub’s Deepfake Porn Crackdown Still Isn’t Working. 2025. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/githubs-deepfake-porn-crackdown-still-isnt-working (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Congressional Research Service. The TAKE IT DOWN Act: A Federal Law Prohibiting the Nonconsensual Publication of Intimate Images. 2025. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/LSB11314 (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Associated Press. President Trump Signs Take It Down Act, Addressing Nonconsensual Deepfakes. What Is It? 2025. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/741a6e525e81e5e3d8843aac20de8615 (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Financial Times. ‘Do not Trust Your Eyes’: AI Generates Surge in Expense Fraud. 2025. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/0849f8fe-2674-4eae-a134-587340829a58 (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- SAP Concur. Fake Receipts 2.0: Why Human Audits Fail Against AI and How Tech Is Fighting Back. 2025. Available online: https://www.concur.com/blog/article/fake-receipts-20-why-human-audits-fail-against-ai-and-how-tech-is-fighting-back (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- ICAEW. Expenses Fraud: How to Spot an AI-Generated Receipt. 2025. Available online: https://www.icaew.com/insights/viewpoints-on-the-news/2025/nov-2025/expenses-fraud-how-to-spot-an-ai-generated-receipt (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- PYMNTS. Ramp Adds AI Agents for Invoice Processing. 2025. Available online: https://www.pymnts.com/news/artificial-intelligence/2025/ramp-adds-ai-agents-invoice-coding-approval-payment-processing/ (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Financial Times. Fraudsters Use AI to Fake Artwork Authenticity and Ownership. 2025. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/fdfb5489-daa0-4e7e-97b7-4317514cd9f4 (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Autio, C.; Schwartz, R.; Dunietz, J.; Jain, S.; Stanley, M.; Tabassi, E.; Hall, P.; Roberts, K. Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework: Generative Artificial Intelligence Profile. 2024. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/publications/artificial-intelligence-risk-management-framework-generative-artificial-intelligence (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- GitHub Advisory Database. PyTorch Model Files Can Bypass Pickle Scanners via Unexpected Pickle Extensions (CVE-2025-1889). 2025. Available online: https://github.com/advisories/GHSA-769v-p64c-89pr (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- OWASP GenAI Security Project. OWASP Gen AI Incident & Exploit Round-Up, Jan–Feb 2025 (nullifAI Malicious Models on Hugging Face Hub). 2025. Available online: https://genai.owasp.org/2025/03/06/owasp-gen-ai-incident-exploit-round-up-jan-feb-2025/ (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Hubinger, E.; Denison, C.; Mu, J.; Lambert, M.; Tong, M.; MacDiarmid, M.; Lanham, T.; Ziegler, D.M.; Maxwell, T.; Cheng, N.; et al. Sleeper agents: Training deceptive llms that persist through safety training. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.05566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Xu, H.; Xing, Y.; Liu, H.; Yamada, M.; Tang, J. Data Poisoning for In-context Learning. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2025, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 29 April–4 May 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ye, J.; Tsai, B.; Ferrara, E.; Luceri, L. Synthetic politics: Prevalence, spreaders, and emotional reception of AI-generated political images on X. In Proceedings of the 36th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media, Chicago, IL, USA, 15–19 September 2025; pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Luceri, L.; Ferrara, E. Auditing Political Exposure Bias: Algorithmic Amplification on Twitter/X During the 2024 US Presidential Election. In Proceedings of the 2025 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Athens, Greece, 23–26 June 2025; pp. 2349–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.K.; Ritchie, N.; Blumenthal, P.; Parsons, A.; Zhang, A.X. Examining the impact of provenance-enabled media on trust and accuracy perceptions. Proc. ACM-Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2023, 7, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luceri, L.; Salkar, T.V.; Balasubramanian, A.; Pinto, G.; Sun, C.; Ferrara, E. Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior on TikTok: Challenges and Opportunities for Detection in a Video-First Ecosystem. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 27–29 May 2026. [Google Scholar]

- European Institute for Gender Equality. Combating Cyber Violence Against Women and Girls; Report; European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE): Vilnius, Lithuania, 2022; Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/combating_cyber_violence_against_women_and_girls.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Ferrara, E. Fairness and bias in artificial intelligence: A brief survey of sources, impacts, and mitigation strategies. Sci 2024, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.