Abstract

Recent developments in natural language processing, particularly large language models (LLMs), create new opportunities for literary analysis in underexplored languages like Romanian. This study investigates stylistic heterogeneity and genre blending in 175 late 19th- and early 20th-century Romanian novels, each classified by literary historians into one of 17 genres. Our findings reveal that most novels do not adhere to a single genre label but instead combine elements of multiple (micro)genres, challenging traditional single-label classification approaches. We employed a dual computational methodology combining an analysis with Romanian-tailored linguistic features with general-purpose LLMs. ReaderBench, a Romanian-specific framework, was utilized to extract surface, syntactic, semantic, and discourse features, capturing fine-grained linguistic patterns. Alternatively, we prompted two LLMs (Llama3.3 70B and DeepSeek-R1 70B) to predict genres at the paragraph level, leveraging their ability to detect contextual and thematic coherence across multiple narrative scales. Statistical analyses using Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney tests identified genre-defining features at both novel and chapter levels. The integration of these complementary approaches enhances microgenre detection beyond traditional classification capabilities. ReaderBench provides quantifiable linguistic evidence, while LLMs capture broader contextual patterns; together, they provide a multi-layered perspective on literary genre that reflects the complex and heterogeneous character of fictional texts. Our results argue that both language-specific and general-purpose computational tools can effectively detect stylistic diversity in Romanian fiction, opening new avenues for computational literary analysis in limited-resourced languages.

1. Introduction

1.1. Definition of Literary Genres and Microgenres

Literature is most often understood as an artistic practice through which an author, by representing a given reality, conveys emotions and meanings using a distinctive language, to elicit a specific reaction from the reader. This definition is broadly accepted within literary studies, although different schools of thought have, at various times, emphasized one or another of its four components: the author, the literary discourse, the represented world, or the reader [1].

Such variations in the understanding of literature arise not only from philosophical or ideological disagreements among critics and estheticians, but also from the simple fact that literature manifests itself in a wide variety of forms, commonly known as “genres.” While the classification of individual genres has been a concern since Aristotle [2], it was only in the mid-twentieth century that the very concept of genre became the object of sustained theoretical debate [3]. Structuralist theorists, such as Tzvetan Todorov [4] and Gérard Genette [5], sought to reformulate traditional rhetorical taxonomies using the tools of modern linguistics. Their efforts, however, faced challenges both from Jacques Derrida’s deconstructionist critiques [6] and from the renewed attention to Mikhail Bakhtin’s writings on heteroglossia, underscoring how multiple voices within a text destabilize generic boundaries [7,8]. In response, post-structuralist thinkers, especially those working within reader-response criticism, such as Hans Robert Jauss [9], Stanley Fish [10], and Alastair Fowler [11], proposed a new understanding of genre—not as a set of fixed categories, but as interpretive conventions, continually negotiated (and thereby transformed) with different communities of readers.

The usefulness of using generic categories has, in recent decades, led to a revival of genre analysis, carried out not only with regard to “central” or “major” languages and literatures (English, French, etc.), but also with respect to literatures often described as “peripheral” or “minor”. Yet, studying a genre such as the novel within a so-called “minor” or “peripheral” literature, like Romanian, as we set out to do in this article, raises two conceptual problems from the outset. The first is more general and concerns the “vertical” order of forms. While it is now broadly acceptable to treat the novel as a “genre” rather than as a mere “species” (a view reinforced by theorists such as Genette [5]), the designation of its subdivisions remains problematic. The reason is that the novel is not a genre like any other but, as Moretti [12] puts it, an “ecosystem” of forms. With respect to the “species” of the novel, several notions have been proposed, including “subgenres” [13,14] and “microgenres” [15]. At present, however, there is no international consensus as to whether, for example, “the graduate student novel” is a “subgenre” (as Walz [16] calls it) or merely a “microgenre” of the broader “campus/university novel”. For this reason, we employ the term microgenre to denote any form of the novel, whether broad (e.g., the social novel) or highly specific (e.g., the outlaw novel).

One reason for this choice is that the concept of microgenre allows us to better articulate our working hypothesis—namely, that the (micro)generic properties of a text can be identified not only at the macro-textual level (that of the work as a whole) but also at the micro-textual level of chapters, paragraphs, or even smaller fragments of text. This hypothesis, and the corresponding term, although employed not on novelistic microgenres, but rather non-novelistic microgenres, was also adopted in a project of the Stanford Literary Lab (“Microgenres"), which was, however, abandoned before its results and underlying data could be formally published [17]. Accordingly, in this article, we use microgenre in two connected but distinct senses, which we believe can be easily distinguished in context—first, as a form/subdivision of the novel genre (=MG1), such as the sentimental novel or the historical novel; and second, as a novelistic fragment (=MG2) that preserves the generic properties of one or more microgenres (=MG1).

The second difficulty in studying the Romanian novel involves the “horizontal” conceptualization of its microgenres (=MG1). This issue has recently been taken up in several discussions, including Borza et al. [18], Terian [19], and Baghiu [20]. The problems stem largely from the fact that the notions and meanings of microgenres in French or English literatures do not necessarily coincide with those in peripheral literatures such as Romanian; moreover, Romanian literature has produced more or less original forms of its own, such as the outlaw novel [21,22,23], which raises questions about the terminological equivalences across cultural systems. Since a detailed analysis of these issues would exceed the scope of this article, we will, for present purposes, adopt the taxonomic system (and corresponding classifications) used in the most recent edition of the Chronological Dictionary of the Romanian Novel [24], which remains the standard reference work in this field.

1.2. Analysis of Literary (Micro)Genres

The study of literary genres has traditionally been rooted in qualitative analysis [11,12,25,26,27,28,29,30] and has relied on human interpretation to classify works based on overarching themes, stylistic features, and ethnic contexts. However, in recent years, literary scholars have begun to apply quantitative methods to the study of microgenres, treating chapters, paragraphs, or even fixed-length text chunks as discrete analytical units. Statistical techniques such as principal component analysis and canonical discriminant analysis have been employed in research to identify authorial styles and distinguish between authors [31]. Researchers have used psychometrically validated word categories to assess differences in genres such as mystery, science fiction, and fantasy [32]. Others have attempted to classify literary microgenres from features such as common words, character networks, and topic models [33].

The quantification of literary works remains contentious, with scholars debating both the potential and limitations of such techniques in comparison to traditional qualitative methods [34]. Taking the quantitative approach one step further, recent studies explore computational methods for literary analysis, offering new insights into text structure and meaning. Monte-Serrat et al. [35] applied machine learning techniques to classify Portuguese literary genres, while Preeti et al. [36] used text mining, natural language processing (NLP), and network analysis to find linguistic patterns and visualize connections within texts. This paradigm shift aligns with the concept of distant reading, introduced by Franco Moretti [37], which advocates a macro-scale, computational literary analysis [38].

Recent advances in this field have explored complex network approaches to literary classification, utilizing measures such as fractal dimensions and network complexity to distinguish between different text types, including narratives, essays, and research articles [39]. Other approaches include the application of transfer learning [40] and deep-learning frameworks [41] for multi-label genre prediction, demonstrating the effectiveness of pretrained models in classification tasks [42]. Recent shared tasks have highlighted the importance of tackling genre classification in low-resource and multilingual settings, where systems had to perform both monolingual and cross-lingual predictions across diverse languages. Approaches ranged from fine-tuning pretrained multilingual Transformers with limited annotated data [43], to combining monolingual and multilingual transfer strategies for improved robustness [44], and leveraging comprehensive ensembles that integrated lexical, syntactic, and Transformer-based features for better adaptation to underrepresented languages [45]. More recent studies using zero-shot and prompt-based classifications offer promising research paths for low-resource languages. For example, Münker et al. [46] showed that zero-shot prompt-based classification achieves comparable performance to fine-tuned BERT models on German tweets, while Philippy et al. [47] proposed a compelling dictionary-based zero-shot topic classification method, applied to Luxembourgish, which outperforms traditional inference-based approaches.

Applying such computational approaches to late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Romanian literature is especially appealing as rapid political and social transformation coincided with diverse ethnic and aesthetic currents [48]. Observing literary patterns through a quantitative lens is especially engaging in this context, as Romanian authors were actively experimenting with form and content in an effort to position their work within a broader, more universal literary framework [49]. Among the various computational approaches that could characterize this period, genre classification offers particularly promising insights into how Romanian authors navigated between traditional forms and innovative literary experiments. Recent Romanian scholarship on genre analysis is a mixed bag, using both qualitative [50,51] and quantitative methods [52].

Genre classification represents one of the most established applications of computational methods in literary studies, with significant contributions spanning multiple languages and literary traditions. Pioneering work by Kessler [53] established foundational approaches for automatic genre classification, while subsequent studies have refined these methods through machine learning and deep learning techniques [54,55,56,57]. For example, Hettinger [33] used stylometric, topic, and network features to classify different microgenres in German novels using a linear support vector machine (SVM) model.

Although extensive research has already mapped the dominant genres of Romanian novels from this era, including social, psychological, historical, sentimental, outlaw (hajduk), rural, mystery, and others [18,58,59,60], the internal diversity of these works remains inadequately explored. In particular, the blending and coexistence of microgenres within individual novels have received little attention, despite their potential to reveal deeper insights into the literary strategies of the time.

The concept of literary microgenres and genre hybridity has gained traction [61], but a significant gap has appeared in recent computational research specifically focused on intratextual microgenre classification. The exploration of literary microgenre mixtures can benefit from computer-assisted techniques because they help identify features in literary works that would otherwise be overlooked [15]. Recent studies have shown both the potential and limitations of multilingual models for literature analysis in languages with limited training data [62,63,64,65]. General-purpose models like those used in our study show promise for capturing subtle stylistic variations, even in Romanian literary texts where annotated resources are scarce [66,67].

1.3. Current Study Objective

Building on advances in natural language processing, our study aims to extend the use of computational methods to explore differences in writing styles across different literary genres in Romanian novels.

Our research is structured around two specific objectives:

1.3.1. Macro-Level Genre Characterization

We employ computational indices to characterize dominant genres and identify clear, explicable differences between them at a global/macro level. To achieve this, we utilize ReaderBench [68] (https://github.com/readerbench/Readerbench/wiki/Textual-Complexity-Indices, accessed on 9 July 2025), a multi-purpose, multilingual software framework designed to support learners and educators through automated text analysis. It employs advanced Natural Language Processing techniques to assess textual complexity across multiple dimensions, including surface, syntax, semantics, and discourse structure, and it has demonstrated robust performance across diverse linguistic and literary contexts. The system is centered on the evaluation based on cohesion, utilizing Cohesion Network Analysis and a polyphonic model inspired by dialogism. Most notably, ReaderBench is the only integrated computational framework available for Romanian language analysis, and thus most suited to our analysis of Romanian literary texts. Its capability to process Romanian texts has been extensively tested, including language-specific morphological, syntactic, and semantic features. ReaderBench has been applied across diverse contexts, including comparative stylistic analysis of Romanian orators [69], predicting reading comprehension scores from essay features [70], assessing text difficulty in children’s literature [71], and diachronic analysis of journalistic writing styles [72]. The framework’s functionality thus encompasses cohesion-based diagnosis, identification of reading strategies, and textual complexity analysis, all of which have been validated empirically and, therefore, make it a viable method in our study.

The linguistic indices selected as features for this analysis are presented in Section 3.

1.3.2. Microgenre Distribution Analysis

We considered large language models (LLMs) to examine the distribution of microgenres within individual Romanian novels. We did not employ linguistic indices for subgenre prediction since we lacked relevant annotations at the subsection or paragraph level, and global estimation would have been too coarse-grained for meaningful subgenre detection. From the outset, we held the expectation that literary texts represent a mixture of microgenres rather than homogeneous genre categories. Nevertheless, we sought to identify clear, explicable differences between texts while acknowledging their inherently hybrid nature. The LLM-based approach enables us to identify the presence of microgenres within individual works, providing a more nuanced understanding of genre mixing in Romanian literary traditions.

2. Current Study Contributions

The main contributions of our study are as follows:

- We release a publicly available corpus of 175 Romanian novels written by 106 authors. The dataset can be accessed at https://huggingface.co/datasets/upb-nlp/lumro_175_novels/ (accessed on 9 July 2025). The LUMRO corpus also includes and revises the ELTeC-rom corpus (https://github.com/COST-ELTeC/ELTeC-rom, accessed on 9 July 2025), to which it adds 75 more novels.

- We present a detailed analysis of the distinctions in literary genres based on the top discriminative linguistic features, as well as examine the mixtures of literary microgenres within novels. We present our method for microgenre classification, and we release our code as open-source on GitHub. The code can be accessed at https://github.com/upb-nlp/LUMRO (version v1.0.0, accessed on 9 July 2025).

3. Method

3.1. Corpus

The dataset used for this study comprises 175 Romanian novels written between 1845 and 1920, representing a diverse range of literary genres, which were annotated by literary historians and verified against the Chronological Dictionary of Romanian Novels [24]. Table 1 presents the number of novels associated with each genre, providing information on its prevalence within the corpus.

Table 1.

Distribution of novels by genre.

The textual content of the novels underwent computational processing, comprising a sequence of three significant data-cleaning phases. Initially, the text was partitioned into individual chapters through regular expressions and a few manual adjustments, facilitating a structured analysis of narrative organization. Subsequently, a character substitution protocol was implemented using regular expressions according to predetermined guidelines. For example, characters such as ‘ĭ’ were replaced with ‘i’, ‘ĕ’ with ‘ă,’ and ‘ê’ with ‘î,’ thereby harmonizing the text with established linguistic norms. Third, a thorough document filtering was carried out, involving the removal of chapters consisting of either single or exclusively brief paragraphs. These methodical data refinement steps were essential in ensuring data integrity and consistency. This preprocessing approach aligns with recent methodological developments in computational analysis of less-resourced languages, where maintaining linguistic authenticity while ensuring computational tractability remains a key challenge [73,74,75]. By dividing the text as described, we analyzed the dynamics at the paragraph level within each chapter. Our chapter-level analysis assumes that individual chapters predominantly reflect their novel’s primary genre classification. Although this does not capture all intratextual variability, it provides a baseline for assessing linguistic features before introducing LLM-based microgenre detection.

Table 1 shows the distribution of the chapters between the genres analyzed. An intriguing observation is the relatively high number of chapters within the “sensation” genre, particularly considering the presence of only two novels from this genre within the corpus. Both of these novels are written by the same author, who also contributes three additional works to the corpus within social novels, although the latter exhibits a distinctively lower chapter count. This raises the possibility that the phenomenon observed in the “sensation” genre could be attributed to either the genre’s inherent characteristics or the author’s deliberate choice to employ a more diverse structure at the chapter level within this particular literary domain. Another observation is that, despite the corpus containing a slightly larger number of sentimental novels, the historical genre exhibits a higher count of chapters. The same parallel can be drawn between the mystery and murder genres.

3.2. Genre Classification

Our methodology consists of two phases—using ReaderBench [68] to examine the differences between literary genres with respect to textual complexity (e.g., usage of certain morphological or syntactical entities across genres) and using Large Language Models (LLMs) to generate the literary microgenre of a paragraph in order to discern a potential mixture of microgenres within a single novel.

3.2.1. Linguistic Features

ReaderBench extracts textual complexity indices across four primary dimensions. First, surface-level features include word count, sentence length, paragraph structure, and syllable patterns. Metrics such as mean words per sentence (M (Wd/Sent)) and maximum syllables per word (Max (Syllab/Word)) help discriminate between genres.

Second, syntactic features capture grammatical dependencies and sentence structure, including compound dependencies, clausal complements, numerical modifiers, and vocative expressions. Indices like compound dependencies per sentence (M (Dep_compound/Sent)) and maximum clausal complements (Max (Dep_ccomp/Sent)) are particularly relevant for genre differentiation.

Third, morphological features examine part-of-speech distributions and word forms, with particular attention to pronoun usage across persons and types, reflecting narrative perspective and discourse style.

Fourth, discourse-level features include connectors and cohesive devices that link ideas between sentences and paragraphs, such as coordinating connectors, contrast markers, concession indicators, and reason/purpose connectors.

For this analysis, we employed both document-level and chapter-level approaches to capture genre characteristics at different granularities. At the document level, we analyzed linguistic features across entire novels, while chapter-level analysis examined microgenre variations within individual works. Before statistical testing, we implemented a rigorous data preprocessing protocol: genres with fewer than 5 novels were excluded to ensure statistical validity, linguistic features where 80% or more values were identical were removed to eliminate uninformative features, and highly correlated feature pairs (Pearson correlation 0.7) were reduced by removing one index from each pair to avoid multicollinearity.

Statistical significance was assessed using non-parametric tests appropriate for our data distribution. The Kruskal–Wallis test [76] served as our primary method for identifying features that significantly differentiate between literary genres, with a significance threshold of p < 0.05 for document-level analysis. For chapter-level analysis, given the larger number of samples and classes, we applied false discovery rate (FDR) correction [77,78,79,80] with a threshold of 0.001 to control for multiple testing and ensure robust feature selection.

Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using Mann–Whitney U tests [81] to identify specific genre pairs exhibiting the greatest dissimilarity in significant linguistic features. This two-step approach allowed us to first identify globally significant features and then pinpoint which specific genre combinations drive these differences, providing detailed insights into the linguistic characteristics that distinguish Romanian literary genres.

3.2.2. LLMs

In our second phase, we employed two large language models comparatively to detect the literary microgenre of paragraphs: a large-scale general model and a reasoning-specialized model. This approach was designed to obtain robust, cross-validated microgenre predictions by leveraging complementary model paradigms. By operating both models on the same text passages, we can compare their predictions to establish consensus labels, flag paragraphs where predictions conflict, and thus more confidently map the complicated landscape of overlapping microgenres in a single novel.

For model selection, we chose Llama3.3 70B [82] and DeepSeek-R1 70B [83] based on their demonstrated superior performance in various natural language understanding tasks and their open-source availability. Llama3.3 70B represents a state-of-the-art general-purpose model with strong performance across diverse linguistic tasks, while DeepSeek-R1 70B is specifically designed for enhanced reasoning capabilities, making it particularly suitable for the nuanced task of literary genre classification. Both models have shown competitive results on standard benchmarks while being freely accessible for research purposes, ensuring the reproducibility of our methodology. Critically, both models can be quantized and run efficiently on a single A100 GPU, ensuring easy replicability without prohibitive computational costs and making our methodology accessible to researchers with standard academic computing resources.

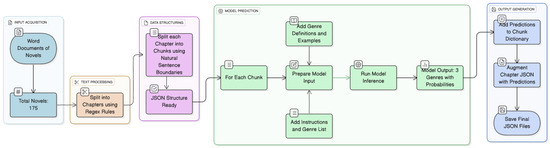

The entire pipeline is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Pipeline for literary microgenre prediction.

To address potential input-length limitations, the chapters were divided into chunks of 2048 tokens, with the split occurring at natural sentence boundaries to ensure that the partitions retained semantic coherence. Text segmentation was performed using a regular expression pattern that identifies punctuation at the end of the sentence (periods, exclamation marks, and question marks) followed by whitespace. The chunking algorithm progressively accumulated complete sentences until the cumulative character count approached the 2048-token threshold. The 2048-token chunk size was selected to balance sufficient contextual information for accurate genre classification with computational efficiency, supplying sufficient narrative context while fulfilling processing time requirements. Nonetheless, the computational analysis still required substantial processing time, which is reflective of both the comprehensiveness of the analysis—processing thousands of text chunks for 175 novels—and the computational intensity of LLM inference.

The instructions given to the LLM consisted of 4 components: a list of all 17 genres present in the corpus, each accompanied by a brief definition; a context specifying the LLM’s role as a literature researcher; the few-shot examples; and the text itself, truncated as previously mentioned. These brief definitions provided the LLM with a clearer framework for interpreting and categorizing the text.

The full prompt, along with the complete list of genres and their definitions, as well as the few-shot examples, is listed in Appendix D. All instructions were provided to the model in Romanian and translated into English for the purposes of this paper. We acknowledge that prompt wording may introduce biases in LLM outputs. Romanian literary terminology and genre conceptualizations may not align perfectly with the models’ training distributions, which could potentially impact classification accuracy. Future work should investigate cross-linguistic effects of prompts.

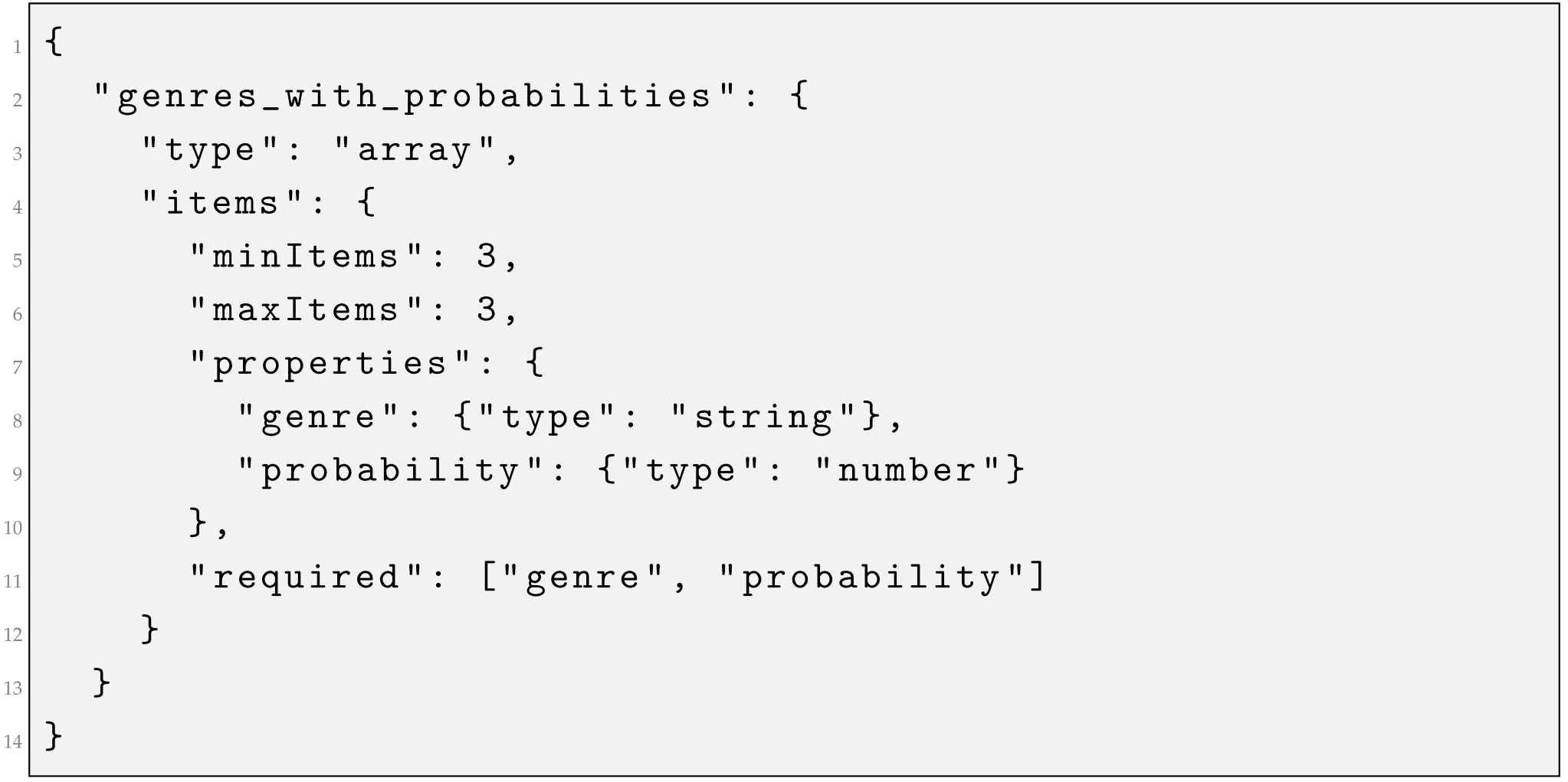

To ensure the output was the expected JSON format, we used a structured output schema, as exposed in Appendix C—Listing A1. The schema reinforces exactly three genre–probability pairs (using minItems and maxItems), where each genre is selected from a predefined list (enum), and each probability is a number between 0 and 1. It performs strict validation (strict:true, additionalProperties:false), ensuring uniform, type-safe outputs.

Both models were used with identical settings, as listed in Table 2. We preferred to use a deterministic configuration with “temperature”:0 and “top_p”:1, which ensured that all tokens with a cumulative probability of up to 1 were included. The option “stream”:False was selected to return the complete response in a single call. Additionally, no penalties were applied for repeating previously generated tokens or for reintroducing tokens that had already appeared in the prompt.

Table 2.

Model settings.

As a result, the output consisted of three predicted genres, along with their respective probabilities per paragraph, for each of the 175 novels. Each probability reflects the model’s confidence that a given paragraph belongs to a specific genre.

We evaluated the task by comparing the resulting top five model-predicted genres for each novel with the single linguist-assigned genre label, and verified if the linguist’s assigned genre fell within the model’s top predictions.

The weighted score for a genre g across an entire novel was computed as follows:

where

- g: a specific genre

- : number of words in paragraph i

- : total number of words in the chapter

- : probability assigned to genre g in paragraph i

- n: number of paragraphs in the chapter

The top five genres were selected based on the highest values of .

The weighted score for genre g over an entire novel addresses the inherent issue of aggregating paragraph-level predictions with coherent document-level classifications. Our approach draws inspiration from time-tested methods in information retrieval and text classification, where longer units of text tend to be assigned higher weights due to their increased statistical reliability and representativeness [84]. The equation accounts for the non-proportional allocation of paragraph length across chapters, whereby longer narrative sections carry proportionally more weight in deciding genre classification than shorter transitional or dialogue passages. This approach aligns with established practices in computational stylistics, where feature importance is weighted by text segment length [85]. We evaluated the performance of the two models based on their ability to predict the annotated genre among the top-K predicted genres.

4. Results

4.1. ReaderBench Linguistic Features

Our initial trials involved applying linguistic features to the Romanian novels, covering both document-level and chapter-level analyses.

4.1.1. Document Level Analysis

We analyzed linguistic features throughout each novel and employed statistical tests, such as the Kruskal–Wallis [76] and Mann–Whitney [81] tests, to determine the indices that exhibited the greatest significance in distinguishing between various literary genres. Before performing these tests, we removed the following: genres with fewer than five novels in our dataset, features for which at least 80% of the values were the same, and a series of indices that were not relevant for the task. We also calculated the Pearson correlation between all possible pairs of the remaining indices and removed one textual index from each highly correlated pair (correlation value greater than or equal to 0.7). The list of genres used in this analysis was the following: historical, social, outlaw, sentimental, murder, war, and mystery.

We first implemented a Kruskal–Wallis test, using a significance threshold of p < 0.05, which resulted in 19 significant linguistic features, presented in Table 3. The H-value represents the test statistic from the Kruskal–Wallis test, with higher values indicating greater differences between the rank distributions of genre groups, meaning that the feature is more discriminative for distinguishing between literary genres.

Table 3.

Significant linguistic features—document analysis.

Compound dependencies ranked first, with χ2 = 44.43 for M (Dep_compound/Sent), reflecting fundamental differences in how Romanian authors construct narrative complexity across genres. Other types of dependencies, such as vocatives, numeral modifiers, and expletives, were among the statistically significant indices. Regarding morphological features, the category of pronouns was notable, having scored two different textual indices: M (Pron_fst/Sent) (χ2 = 31.07) and Max (Pron_snd/Sent) (χ2 = 29.63). High first-person pronoun usage likely indicates autobiographical elements or confessional modes common in social novels, where authors explore individual psychology against societal backdrops. This aligns with the Romanian literary tradition of using personal experience to critique social conditions.

Furthermore, we conducted Mann–Whitney U tests for each significant index with a p value < 0.01 and for each pair of genres. Thus, we computed the top three pairs of genres that presented the highest dissimilarity in relation to each of the indices. Higher scores typically indicate a greater difference between the two groups compared. The findings imply that the pairs social–sentimental, social–historical, and social–murder showcase the highest dissimilarity in linguistic characteristics, and also that the social genre stands out as significantly distinct from other genres.

4.1.2. Chapter-Level Analysis

In alignment with the procedure used for document-level analysis, a similar approach was adopted for chapter-level analysis. However, no genres were excluded from the analysis this time; instead, all 17 literary genres were retained for examination. We followed the same cleaning process and removed an index from each pair of features that had a high Pearson correlation of 0.7 or greater, and the features where the most common value appears with a frequency of 80% or more.

Following this data refinement process, a Kruskal–Wallis test was performed, which revealed significant statistical associations for a substantial proportion of the indices under investigation. Therefore, to obtain more specific results, we used the FDR (false discovery rate) [77,78,79,80], thereby dynamically adjusting the threshold of the p-value. The FDR algorithm works by selecting the features that have a false discovery rate lower than the specified threshold [80], which we chose to be 0.001 due to the large number of samples and classes. Overall, 46 linguistic features emerged as significant and are grouped in Table 4 from the highest H-value to the lowest.

Table 4.

Significant linguistic features—chapter analysis.

We also plotted the values of the significant features across all genres. One example is shown in Figure 2, where the distribution of average words per sentence across different literary genres reveals that mystery and war genres exhibit the highest sentence complexity with the widest range of values (extending up to 90 words per sentence), while most other genres cluster around 15–25 words per sentence with relatively tighter distributions. Further examples are presented in Appendix A, Figure A2.

Figure 2.

Plotted significant surface-level textual indices across genres.

Syntactic complexity and structural elements, such as clausal complements and numerical modifiers, emerge as important factors in distinguishing genres. Pronoun usage also varies notably across genres, alongside differences in sentence and paragraph length and structure, which may indicate variations in pacing, information density, or narrative techniques. Furthermore, the use of connectors linking ideas and clauses varies by genre; for instance, certain genres may rely more heavily on explanatory or contrasting conjunctions, thereby highlighting unique styles of argumentation or storytelling.

Similar to the document-level analysis, we also performed a Mann–Whitney test to gain insights into which genres are the most disparate for the significant features calculated in the previous step. According to the results in Appendix B, Figure A3 and Figure A4, the same three pairs as in the previous step were the most dissimilar: historical versus social, sentimental versus social, and murder versus social.

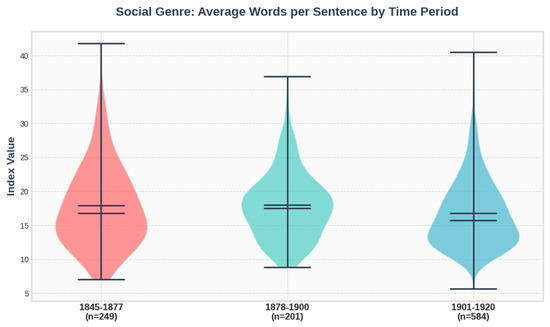

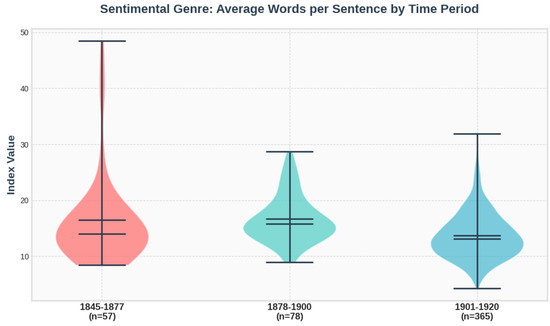

We also aggregated the values of linguistic features by time period and split our corpus into three main ones: 1845–1877, 1878–1900, and 1901–1920. This chronological division reflects two pivotal moments in Romanian history: the War of Independence (1877–1878), which marked Romania’s emergence as a sovereign state, and the turn of the 20th century, a period of significant cultural and literary transformation.

Comparing the corpus’s two dominant genres (social and sentimental), we examined their developmental trajectories across our three historical periods using the ReaderBench metric for average sentence length. The reason for choosing this particular index is that it emerged as the most statistically significant discriminator in our Kruskal–Wallis test of all 17 genres, exhibiting the highest H-value. Figure 3 and Figure 4 show an almost imperceptible change for the social genre and a significant decline for the sentimental, considering also that n represents the number of chapters, and it is the highest in the third period of time.

Figure 3.

Plotted values of average words per sentence for the social genre, by time period.

Figure 4.

Plotted values of average words per sentence for the sentimental genre, by time period.

4.2. Microgenre Prediction with LLMs

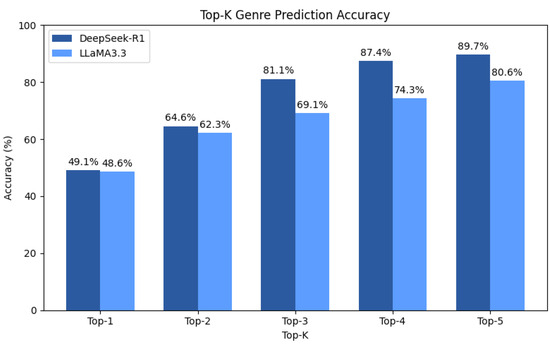

As Figure 5 shows, DeepSeek-R1 consistently outperforms Llama3.3 across all top-K levels. For example, DeepSeek-R1 achieves a top-1 accuracy of 49.14% compared to 48.57% for Llama3.3 and a top-5 accuracy of 89.71% compared to 80.57%.

Figure 5.

Top-K genre prediction accuracy for DeepSeek-R1 and Llama3.3 models.

We also analyzed cases where the predictions from Llama3.3 differed from those of DeepSeek-R1 and compiled a list of the top genre pairs that were assigned differently by the two models, as shown in Table 5. Most of these cases can be explained by overlapping thematic content or stylistic similarity. Both sentimental and poetic texts can be focused on expressing emotions. In our corpus, novels like Traian Demetrescu’s Intim (1892) demonstrate how sentimental narratives employ lyrical passages that blur the boundaries with poetic expression. Both sentimental and psychological can convey feelings and internal turmoil. Works like Elena Bacaloglu’s În luptă (1906) blend sentimental discourse with psychological interiority, exploring the mental states underlying emotional experience. War, historical, and outlaw do not exclude each other, similar to historical and social, and psychological and social. The most intriguing finding concerns the arguably not-so-frequent misalignment between sentimental and social, which our statistical analysis using ReaderBench indices confirmed as the most textually dissimilar pair in terms of complexity measures.

Table 5.

Top 10 most frequently mismatched genre pairs between DeepSeek and Llama predictions.

Further examples are discussed in the Section 5.

5. Discussion

Our research indicates that the textual complexity indices provided by ReaderBench offer valuable insights into the differences in writing styles across various literary genres in Romanian novels. At the document level, the results from the Kruskal–Wallis test revealed several linguistic features that significantly differentiate between genres, particularly with compound dependencies and pronoun usage. The Mann–Whitney U tests further revealed that pairs social–sentimental and social–murder show the highest dissimilarity in terms of linguistic features.

At the chapter level, a broader range of genres was included, which revealed 46 significant features after applying the false discovery rate (FDR) correction. This increased sensitivity enabled more granular insights into the linguistic distinctions between genres. In particular, sentence structure and word difficulty (e.g., M (LemmaDiff/Word)) also play a significant role in genre differentiation at the chapter level. In both analyses, we found that different pronoun usage can discriminate between genres, which echoes Bakhtin’s concept of heteroglossia—the coexistence of multiple voices and discourse types within a single work.

However, a significant limitation of the chapter-level analysis is that we assumed all chapters within a novel belong to the same dominant genre as the novel’s overall classification. This assumption likely oversimplifies the complex reality of genre mixing within individual works, as our LLM analysis later revealed substantial microgenre variation across passages within the same novel. This limitation motivated our subsequent exploratory analysis using large language models to examine genre hybridity at a more granular level.

In the second phase of our study, we analyzed the prevalence of literary microgenre hybrids within individual novels, where large language models (LLMs) proved to be highly effective. DeepSeek-R1 70B outperformed Llama3.3 70B in terms of overall performance.

Figure 6 represents the distribution of different genres that appear in the corpus according to the predictions made by DeepSeek-R1. For each passage, the model assigned the top three genres. These genre probabilities were first aggregated at the chapter level and then averaged across all chapters within each novel. Finally, the percentages were calculated by averaging these values across all novels in the corpus.

Figure 6.

Genre distribution in the Corpus—DeepSeek-R1.

Comparing Figure 6 and Table 1, the major difference that emerges is the discrepancy between the prevalence of certain genres. For example, although the corpus included just one novel strictly classified as psychological, the model often attributed a psychological dimension to many passages (around 22%). We can deduce from this that because many passages exhibited internal thoughts, emotional turmoil, and introspective reflections of the characters, it led the model to identify a solid psychological aspect even in those pieces that were not formally within that genre. It is also interesting to see the increased prevalence of sentimental along with the decline of historical. The two phenomena may or may not be correlated; however, a recent compelling study [86] reveals that Romanian historical novels often incorporate Romantic elements and tend to romanticize historical episodes by adding what is described as a melodramatic twist.

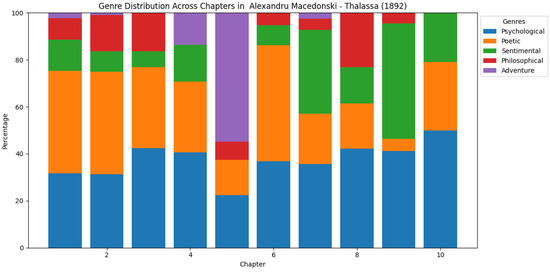

Another notable contrast is between the prevalence of passages predicted as poetic and the presence of only two novels formally classified as such. A potential reason for this could be the challenge in defining what constitutes a poetic novel. The two poetic novels in the corpus were Thalassa by Alexandru Macedonski and Apus în flăcări by Mikael Dan. Thalassa, according to [24], illustrates, with philosophical and poetic overtones, Macedonski’s vision of art. Figure 7 is a representation of the top five predicted genres in Thalassa, and indeed, the first two microgenres are philosophical and poetic.

Figure 7.

Top 5 predicted genres in Thalassa (Alexandru Macedonski, 1892).

Apus în flăcări is also a sensual novel, according to [24], which presents erotic neurosis elements, symbolic synesthetic impressions, and lavish imagination. Figure 8 demonstrates the sentimental dimension of the novel.

Figure 8.

Top 5 predicted genres in Apus în flăcări (Mikael Dan, 1907).

Additional figures are displayed in Appendix E and illustrate the presence of a mixture of literary genres within the same novel. Figure A5 depicts a sentimental novel with added layers of psychological, mystery, social, and adventure nuance. Figure A6 represents a canonical social novel that advances sentimental, psychological, rural, and religious elements as well. Figure A7 represents a historical novel, while Figure A8 is canonically classified as a novel about hajduks (i.e., outlaws).

Another key aspect of our research was to analyze cases where the LLMs gave different predictions as the first genre among the top three predicted for each text. The following is an example of genre classification disagreement between sentimental and social.

Romanian text: “El remase apoi schilod în toată viața lui. Dar înfine el era acuma scăpat și’și redobândise libertatea. Ca o pasăre scăpată din cușcă alergă acasă cu speranța de a’și găsi soția și copiii. Ușa era închisă, obloanele lăsate în jos, ca în zâua când plecase; niciun vecin nu văzuse pe nevasta lui, pe copiii sei și nici nu știa ce s’au făcut. Șloime Haies, călit la durere, scoase un oftat și tărăndu’și piciorul, chemă un lăcătuș, deschise ușa, își scoase banii, și cu durere în piept, cu o nedumerire îngrozitoare în suflet, plecă spre Tărgu-Ocna în căutarea familiei sale.“—Gângavul, Elias Schwarzfeld, 1895

English translation: “He remained lame for the rest of his life. But finally, he was now free and had regained his liberty. Like a bird escaped from its cage, he ran home hoping to find his wife and children. The door was closed, the shutters lowered, as on the day he had left; no neighbor had seen his wife or his children, nor did anyone know what had become of them. Șloime Haies, hardened by suffering, let out a sigh and, dragging his foot, called a locksmith, opened the door, took out his money, and with pain in his chest and terrible bewilderment in his soul, set off for Tărgu-Ocna in search of his family.“

The genres detected by the models for this paragraph are mentioned in Table 6.

Table 6.

Model genre classification comparison.

DeepSeek’s classification prioritizes the social dimension, responding to themes of societal displacement and community disruption, with secondary classifications of psychological and biographical, emphasizing individual psychological experience and life narrative.

In contrast, Llama identifies the passage as primarily sentimental, focusing on the emotional resonance of loss and despair. Its secondary predictions: historical and exile, suggest recognition of historical context and displacement themes within the Romanian literary tradition.

The novel itself presents a history of Jews in Romania, particularly in Neamț and Bacău counties, and intriguingly, it has a strong autobiographical component. At the same time, he was exiled in Paris in April 1894 [24]. It can be debated whether the author’s own exile influenced his writing style, but considering that the way we defined the genre exile in the prompt inclines towards the state of being far from one’s homeland rather than the narrative style having certain features, the hypothesis remains speculative. The novel is canonically categorized as social and, therefore, this example showcases again the outperformance of DeepSeek.

This divergence between models highlights a deeper theoretical point: the instability of genre itself. As Derrida [6] argues in The Law of Genre,

Every text participates in one or several genres, there is no genreless text; there is always a genre and genres, yet such participation never amounts to belonging.

At the same time, he stresses that this participation is never pure and that genres are always in tension, overlapping and destabilizing their own boundaries.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Our study challenges the concept of categorizing a novel within a single literary genre, demonstrating that these literary works possess a hybrid composition. Our multi-level analysis also reveals key linguistic features in discriminating between the literary genres. Both methods, ReaderBench’s linguistic features and LLMs’ genre prediction, offer a scalable approach for large-scale literary analysis.

Further research could expand this methodology to investigate the temporal evolution of genre characteristics and microgenre hybrids across the 1845–1920 period covered by our corpus, as well as extend the analysis to a broader historical time frame. Such a diachronic investigation would potentially reveal how genres of literature transformed during this crucial period of Romanian literary development, potentially identifying patterns of genre creation, consolidation, and synthesis over time. The establishment of more sophisticated genre taxonomies specifically designed for Romanian literature would further enhance the accuracy of such research. The literary microgenre detection could also benefit from expert annotations at the paragraph level, which can be used in the training process of machine learning models or for better validating the LLM predictions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R. and M.D.; Data curation, A.C.U.; Formal analysis, S.R., A.T. and M.D.; Funding acquisition, A.T.; Investigation, A.C.U.; Methodology, A.C.U. and S.R.; Project administration, A.T.; Resources, V.P., S.R. and A.T.; Supervision, M.D.; Validation, M.D.; Writing—original draft, A.C.U.; Writing—review & editing, S.R., V.P., S.B., A.T. and M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Research, Innovation, and Digitization, CNCS-UEFISCDI, project number PN-IV-P1-PCE-2023-2025 LUMRO, within PNCDI IV.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available at https://huggingface.co/datasets/upb-nlp/lumro_175_novels/ and https://github.com/upb-nlp/LUMRO.git.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used EraserAI (accessed July 2025) for the purposes of creating diagrams and Claude Sonnet 4 for the purposes of improving text clarity in Section 3, Section 3.2.2 and Section 5. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Data Availability Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| Llama | Large Language Model Meta AI |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| POS | Part of Speech |

Appendix A. Plots of Significant Linguistic Feature Values Across Genres

Figure A1.

Plotted significant linguistic features across genres—Bigram Entropy.

Figure A2.

Plotted significant linguistic features across genres—Indirect Objects.

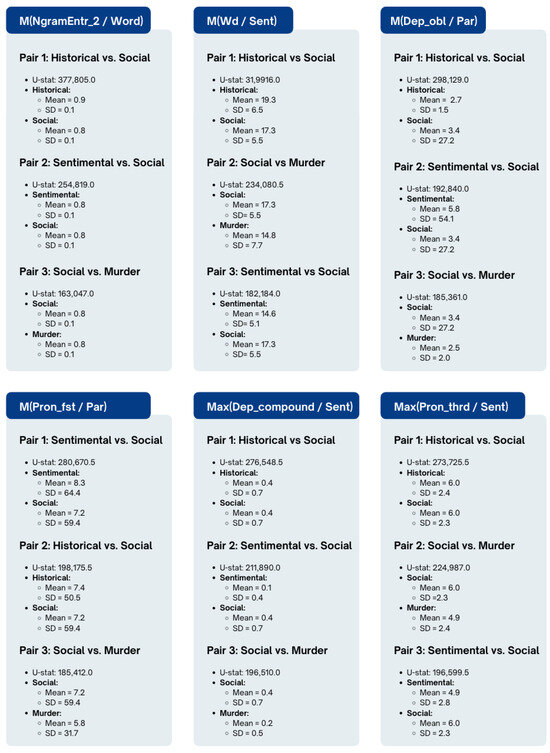

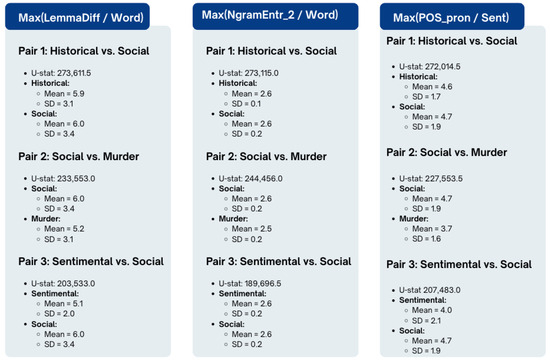

Appendix B. Mann–Whitney U Test Results

This appendix presents the complete Mann–Whitney U test results for pairwise comparisons across different linguistic features and semantic categories.

Figure A3.

Mann–Whitney U test results for N-gram entropy, word dependency, and dependency object features. Statistical comparisons.

Figure A4.

Mann–Whitney U test results for lemma difference, N-gram entropy, and pronoun features. Statistical comparisons.

Appendix C. Structured Output Schema

| Listing A1. Output schema for genre probabilities. |

|

Appendix D. Full System Prompt Used in Genre Prediction by LLM

Table A1.

System Prompt used for Literary Genre Prediction.

Table A1.

System Prompt used for Literary Genre Prediction.

| System Prompt |

|---|

You are a literature researcher and you need to specify the literary genre of a fragment from a Romanian novel. These are the possibilities:

|

| Examples of correct classification: |

Example 1:

|

| Correctly generated genres and probabilities: {“genres_with_probabilities”: [ “genre”: “outlaw”, “probability”: “0.6”, “genre”: “adventure”, “probability”: “0.3”, “genre”: “historical”, “probability”: “0.1”]} |

Example 2:

|

| Correctly generated genres and probabilities: {“genres_with_probabilities”: [ “genre”: “science fiction”, “probability”: 0.7, “genre”: “adventure”, “probability”: 0.2, “genre”: “historical”, “probability”: 0.1]} |

Example 3:

|

| Correctly generated genres and probabilities: {“genres_with_probabilities”: [ “genre”: “rural”, “probability”: 0.8, “genre”: “social”, “probability”: 0.15, “genre”: “poetic”, “probability”: 0.05]} |

Appendix E. Examples of Genre Distribution

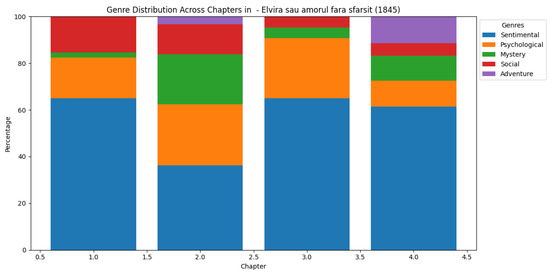

Elvira sau amorul fără sfârșit (Figure A5) is a novel canonically classified as sentimental, considered to be one of the first Romanian modern novels. The story takes place in Spain, where the beauty and misfortune of Elvira, oppressed by a tyrannical husband, attracts the sincere interest of a new lover. Their love is considered sinful and condemned by society, leading to a tragic ending. Elvira commits suicide, her husband remains inconsolable, and her lover disappears into the world. This romantic case of “unhappy love” establishes a typology in Romanian popular literature [24].

Figure A5.

Top 5 Predicted Genres in Elvira sau amorul fără sfârșit (D.F.B., 1845).

Mara (Figure A6) is regarded as a social novel following the struggles of a widow, Mara, as she navigates the difficulties of single motherhood while raising her two children, depicting their transition from childhood into adulthood. As Mara becomes wealthier, her children encounter serious conflicts: her daughter secretly marries a German butcher’s son despite social prejudices, while her son enlists in the Austrian army against his master’s wishes. According to G. Călinescu [24], an acclaimed Romanian literature critic and author:

half of the novel slowly and patiently chronicles the awakening, development, and eruption of love in a girl conscious of her beauty and charms, first provocative and undecided, then mastered by passion and capable of any sacrifice.

Figure A6.

Top 5 predicted genres in Mara (Ioan Slavici, 1906).

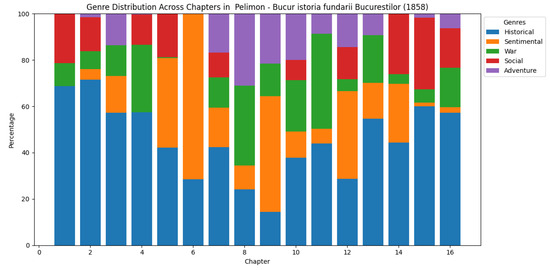

Bucur istoria fundarii Bucurestilor (Figure A7) is a historical novel [24]. The story depicts Prince Bucur’s marriage to Ileana of Moldavia after rescuing her from Tatar captivity, leading to the founding of Bucharest and serving as an allegory for Romanian unification.

Figure A7.

Top 5 predicted genres in Bucur istoria fundarii Bucurestilor (Al. Pelimon, 1858).

Boierii haiduci (Figure A8) is an outlaw novel [24], a hajduk tale featuring extraordinary adventures, abductions, and dramatic chases.

Figure A8.

Top 5 predicted genres in Boierii haiduci (N.D. Popescu, 1892).

References

- Krieger, M. Theory of Criticism; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle, B. Poetics; Janko, R., Translator; Hackett Publishing Company: Indianapolis, IN, USA; Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, T. Genre Theory and Historicism. J. Cult. Anal. 2016, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorov, T. Genres in Discourse; Porter, C., Translator; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Genette, G. The Architext: An Introduction; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA; Los Angeles, CA, USA; Oxford, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, J. The law of genre. Crit. Inq. 1980, 7, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, V. Eteroglossia/Heteroglossia. In Culture e Discorso. Un Lessico per le Scienze Umane, a Cura di Alessandro Duranti; Meltemi Editore: Rome, Italy, 2002; pp. 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, V.V. Bakhtin’s theory of language from the standpoint of modern science. Russ. J. Commun. 2008, 1, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauss, H.R. Literary History as a Challenge to Literary Theory. New Lit. Hist. 1970, 2, 7–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, S. Is There a Text in This Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, A. Kinds of Literature: An Introduction to the Theory of Genres and Modes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, F. The Novel, 1. History, Geography, Culture; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, G. The diary novel: Notes for the definition of a sub-genre. Neophilologus 1975, 59, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, D. Modern Genre Theory; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D. A Review of The Microgenre: A Quick Look at Small Culture. Interdiscip. Lit. Stud. 2023, 25, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walz, K. The Graduate Student Novel: A New Subgenre in University Fiction. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Missouri, Columbia, MI, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stanford Literary Lab. Microgenres. Available online: https://litlab.stanford.edu/projects/microgenres/ (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Borza, C.; Goldiș, A.; Tudurachi, A. Subgenurile Romanului Românesc. Laboratorul unei tipologii. Dacorom. Litt. 2020, 7, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terian, A. Principles for an Evolutionary Taxonomy of the Romanian Novel. Transylv. Rev. 2022, 31, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Baghiu, Ș. Apartenența multiplă de subgen: O propunere pentru istoria formelor românești. Rev. Transilv. 2022, 11–12, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöch, C.; Erjavec, T.; Patras, R.; Santos, D. Creating the european literary text collection (eltec): Challenges and perspectives. Mod. Lang. Open 2021, 25, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patras, R. Romanian Novel Corpus (ELTeC-rom): Release with 80 novels encoded at level 1. In European Literary Text Collection; Zenodo: Genève, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patras, R.; Odebrecht, C.; Galleron, I.; Arias, R.; Herrmann, B.J.; Krstev, C.; Poniž, K.M.; Yesypenko, D. Thresholds to the “Great Unread”: Titling Practices in Eleven ELTeC Collections. Interférences Littéraires/Literaire Interf. 2021, 25, 163–187. [Google Scholar]

- Tudurachi, A. Dicționarul Cronologic al Romanului Românesc de la Origini până în 2000 [Chronological Dictionary of the Romanian Novel from Its Origins to 2000]; Presa Universitară Clujeană: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2023; Volume I–II. [Google Scholar]

- Todorov, T. Literary genres. Curr. Trends Linguist. 1974, 12, 957–962. [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger, K. The Logic of Literature; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Beebee, T.O. The Ideology of Genre: A Comparative Study of Generic Instability; Penn State Press: University Park, PA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bawarshi, A. The Genre Function. Coll. Engl. 2000, 62, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frow, J. Genre; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, R. Genre Theory and Historical Change: Theoretical Essays of Ralph Cohen; University of Virginia Press: Richmond, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, R.D.; Hengartner, N.W. Quantitative analysis of literary styles. Am. Stat. 2002, 56, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, R.; Lynn, J.; Purzycki, B.G. Toward a science of science fiction: Applying quantitative methods to genre individuation. Sci. Study Lit. 2014, 4, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettinger, L.; Reger, I.; Jannidis, F.; Hotho, A. Classification of Literary Subgenres. In Proceedings of the DHd, Krakow, Poland, 11–16 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Herawati, Y.W.; Masitoh, S. Quantifying literary works: Is it possible? J. Ilm. Bhs. Dan Sastra 2024, 11, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte-Serrat, D.M.; Machado, M.T.; Ruiz, E.E.S. A machine learning approach to literary genre classification on Portuguese texts: Circumventing NLP’s standard varieties. In Proceedings of the Simpósio Brasileiro de Tecnologia da Informação e da Linguagem Humana (STIL), Online, 2021; Sociedade Brasileira de Computação (SBC): Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil, 2021; pp. 255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Preeti; Sharma, N.; Verma, J.; Latha, R.; Dharanish, J.; Bheemra. Quantitative Analysis of Literary Texts: Computational Approaches in Digital Humanities Research. Educ. Adm. Theory Pract. 2024, 30, 5234–5240. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, F. Distant Reading; Verso Books: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, F. Canon/Archive: Studies in Quantitative Formalism from the Stanford Literary Lab; n + 1 Foundation: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Arellano, A. Classification of Literary Works: Fractality and Complexity of the Narrative, Essay, and Research Article. Entropy 2020, 22, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, C.L.; Ho, C.K.; Aung, T.H.; Koh, Y.Y.; Teo, T.H. Transfer learning and deep neural networks for robust intersubject hand movement detection from EEG signals. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, C.L.; Ho, C.K.; Chen, L.; Koh, Y.Y.; Tian, B. A novel predictive modeling for student attrition utilizing machine learning and sustainable big data analytics. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, F.Z.; Guzel, M.S.; Bostanci, E.; Acici, K.; Asuroglu, T. Multilabel Genre Prediction Using Deep-Learning Frameworks. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devatine, N.; Muller, P.; Braud, C. MELODI at SemEval-2023 Task 3: In-domain Pre-training for Low-resource Classification of News Articles. In Proceedings of the 17th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation, Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lepekhin, M.; Sharoff, S. FTD at SemEval-2023 Task 3: News Genre and Propaganda Detection by Comparing Mono- and Multilingual Models with Fine-tuning on Additional Data. In Proceedings of the 17th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation, Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y. Team QUST at SemEval-2023 Task 3: A Comprehensive Study of Monolingual and Multilingual Approaches for Detecting Online News Genre, Framing and Persuasion Techniques. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.04190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münker, S.; Kugler, K.; Rettinger, A. Zero-shot prompt-based classification: Topic labeling in times of foundation models in German Tweets. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.18239v1. [Google Scholar]

- Philippy, F.; Haddadan, S.; Guo, S. Forget NLI, Use a Dictionary: Zero-Shot Topic Classification for Low-Resource Languages with Application to Luxembourgish. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.03912. [Google Scholar]

- Baghiu, S. The Rise of Translations: Foreign Novels in Romania in 1877, 1945, and 1989. Transylv. Rev. 2022, 31, 250–260. [Google Scholar]

- Terian, A. Big numbers: A quantitative analysis of the development of the novel in Romania. Transylv. Rev. 2019, 28, 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Varga, D. ND Popescu și romanele istorice de consum. Rev. Transilv. 2023, 11–12, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gârdan, D. Evoluţia romanului erotic românesc din prima jumătate a secolului al XX-lea. Intre exerciţiu si canonizare. Rev. Transilv. 2018, 7, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Borza, C.; Gârdan, D.; Modoc, E. The peasant and the nation plot: A distant reading of the Romanian rural novel from the first half of the twentieth century. Rural. Hist. 2023, 34, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, B.; Nunberg, G.; Schütze, H. Automatic Detection of Text Genre. In 35th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and 8th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Association for Computational Linguistics: Madrid, Spain, 1997; pp. 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Santini, M. Automatic genre identification: Towards a flexible classification scheme. In Proceedings of the BCS IRSG Symposium: Future Directions in Information Access 2007. BCS Learning & Development, Glasgow, UK, 28–29 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Petrenz, P.; Webber, B. Robust cross-lingual genre classification through comparable corpora. In Proceedings of the The 5th Workshop on Building and Using Comparable Corpora, Istanbul, Turkey, 26 May 2012; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Maharjan, S.; Montes, M.; González, F.A.; Solorio, T. A genre-aware attention model to improve the likability prediction of books. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–4 November 2018; pp. 3381–3391. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, A.; Prem Prakash, V. Statistical and deep learning approaches for literary genre classification. In Advances in Data and Information Sciences: Proceedings of ICDIS 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Terian, A.; Gârdan, D.; Modoc, E.; Borza, C.; Varga, D.; Olaru, O.; Morariu, D. Genurile romanului românesc (1901–1932). O analiză cantitativă. Transilvania 2020, 10, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patraș, R. Hajduk novels in the nineteenth-century Romanian fiction: Notes on a sub-genre. Swed. J. Rom. Stud. 2019, 2, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ursu, M.G. Romanul misterelor în literatura română a secolului al XIX-lea-o pagină de istorie literară uitată. Swed. J. Rom. Stud. 2022, 5, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, A.H.; O’Donnell, M.C. The Microgenre: A Quick Look at Small Culture; Bloomsbury Publishing USA: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Tu, Z.; Chen, C.; Yuan, Y.; Huang, J.t.; Jiao, W.; Lyu, M.R. All languages matter: On the multilingual safety of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.00905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalcea, R.; Ignat, O.; Bai, L.; Borah, A.; Chiruzzo, L.; Jin, Z.; Kwizera, C.; Nwatu, J.; Poria, S.; Solorio, T. Why AI Is WEIRD and Shouldn’t Be This Way: Towards AI for Everyone, with Everyone, by Everyone. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 28657–28670. [Google Scholar]

- Nasution, A.H.; Onan, A. Chatgpt label: Comparing the quality of human-generated and llm-generated annotations in low-resource language nlp tasks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 71876–71900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H.; Pan, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, H.; et al. Opportunities and challenges of large language models for low-resource languages in humanities research. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.04497. [Google Scholar]

- Repede, S.E.; Brad, R. LLaMA 3 vs. State-of-the-Art Large Language Models: Performance in Detecting Nuanced Fake News. Computers 2024, 13, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ştefănescu, E.; Jerpelea, A.I. Reddit is all you need: Authorship profiling for Romanian. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.09907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dascalu, M.; Dessus, P.; Trausan-Matu, Ş.; Bianco, M.; Nardy, A. ReaderBench, an environment for analyzing text complexity and reading strategies. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence in Education: 16th International Conference, AIED 2013, Memphis, TN, USA, 9–13 July 2013; Proceedings 16. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 379–388. [Google Scholar]

- Dascalu, M.; Gîfu, D.; Trausan-Matu, S. What Makes Your Writing Style Unique? Significant Differences Between Two Famous Romanian Orators. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Collective Intelligence, Halkidiki, Greece, 28–30 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L.; Dascalu, M.; McNamara, D.S.; Crossly, S.; Trausan-Matu, S. Modeling individual differences among writers using ReaderBench. In Proceedings of the EDULearn16: 8th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Barcelona, Spain, 4–6 July 2016; IATED Academy: Valencia, Spain, 2016; pp. 5269–5279. [Google Scholar]

- Chitez, M.; Dascalu, M.; Udrea, A.C.; Strilețchi, C.; Csürös, K.; Rogobete, R.; Oravițan, A. Towards Building the LEMI Readability Platform for Children’s Literature in the Romanian Language. In Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024), Torino, Italy, 20–25 May 2024; Calzolari, N., Kan, M.Y., Hoste, V., Lenci, A., Sakti, S., Xue, N., Eds.; pp. 16450–16456. [Google Scholar]

- Gifu, D.; Dascalu, M.; Trausan-Matu, S.; Allen, L.K. Time evolution of writing styles in Romanian language. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 28th International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (ICTAI), San Jose, CA, USA, 6–8 November 2016; pp. 1048–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, K.V.; Kumar, R. Data Preprocessing Techniques. Phoenix: Int. Multidiscip. Res. J. 2025, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Meetei, L.S.; Singh, T.D.; Borgohain, S.K.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Low resource language specific pre-processing and features for sentiment analysis task. Lang. Resour. Eval. 2021, 55, 947–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.; Mallick, D.D.; Khan, M.S.I.; Hasan, M.M.; Ashraf, F.B. An efficient text preprocessing and classification technique for multilingual and transliterated data. In Proceedings of the 2022 25th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT), Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, 17–19 December 2022; pp. 366–371. [Google Scholar]

- Vargha, A.; Delaney, H.D. The Kruskal-Wallis Test and Stochastic Homogeneity. J. Educ. Stat. 1998, 23, 170–192. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, J.D. False Discovery Rate. Int. Encycl. Stat. Sci. 2011, 1, 504–508. [Google Scholar]

- Pilnenskiy, N.; Smetannikov, I. Feature selection algorithms as one of the python data analytical tools. Future Internet 2020, 12, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.A. A Study on Comparative Analysis of Feature Selection Algorithms for Students Grades Prediction. J. Inf. Organ. Sci. 2024, 48, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, P.E.; Najab, J. Mann-Whitney U Test. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Grattafiori, A.; Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Vaughan, A.; et al. The Llama 3 Herd of Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.21783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Song, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, R.; Zhu, Q.; Ma, S.; Wang, P.; Bi, X.; et al. Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.12948. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, C.D. An Introduction to Information Retrieval; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jockers, M.L. Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Olteanu, A. The Romantic Historicism and the risse of the Historical Novel in the 19 (tm) century Romanian Literature. Philobiblon 2024, 29, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).