Interfacial Molecular Interactions as Determinants of Nanostructural Preservation in Ibuprofen-Loaded Nanoemulsions and Nanoemulsion Gels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Determination of Ibuprofen Solubility in Selected Oils, Surfactants, and Co-Solvents

2.2.2. Construction of Pseudo-Ternary Phase Diagrams

2.2.3. Sample Preparation

Nanoemulsion Formation Via Emulsion Phase Inversion (EPI) Method

Transformation of Nanoemulsions into Nanoemulsion Gels

2.2.4. Determination of Droplet Size, Surface Charge, and Polydispersity Index of Nanoemulsions and Nanoemulsion Gels

2.2.5. Electrical Conductivity

2.2.6. pH Value

2.2.7. Stability Assessment

2.2.8. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

2.2.9. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.2.10. Encapsulation Efficacy Study

2.2.11. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Spectroscopy

2.2.12. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

2.2.13. Rheological Behavior

2.2.14. In Vitro Release Testing (IVRT) of Nanoformulations

2.2.15. Ibuprofen Quantification

2.2.16. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Interfacial Properties Governing Nanoemulsions’ Performance

3.1.1. Selection of Nanoemulsion Components

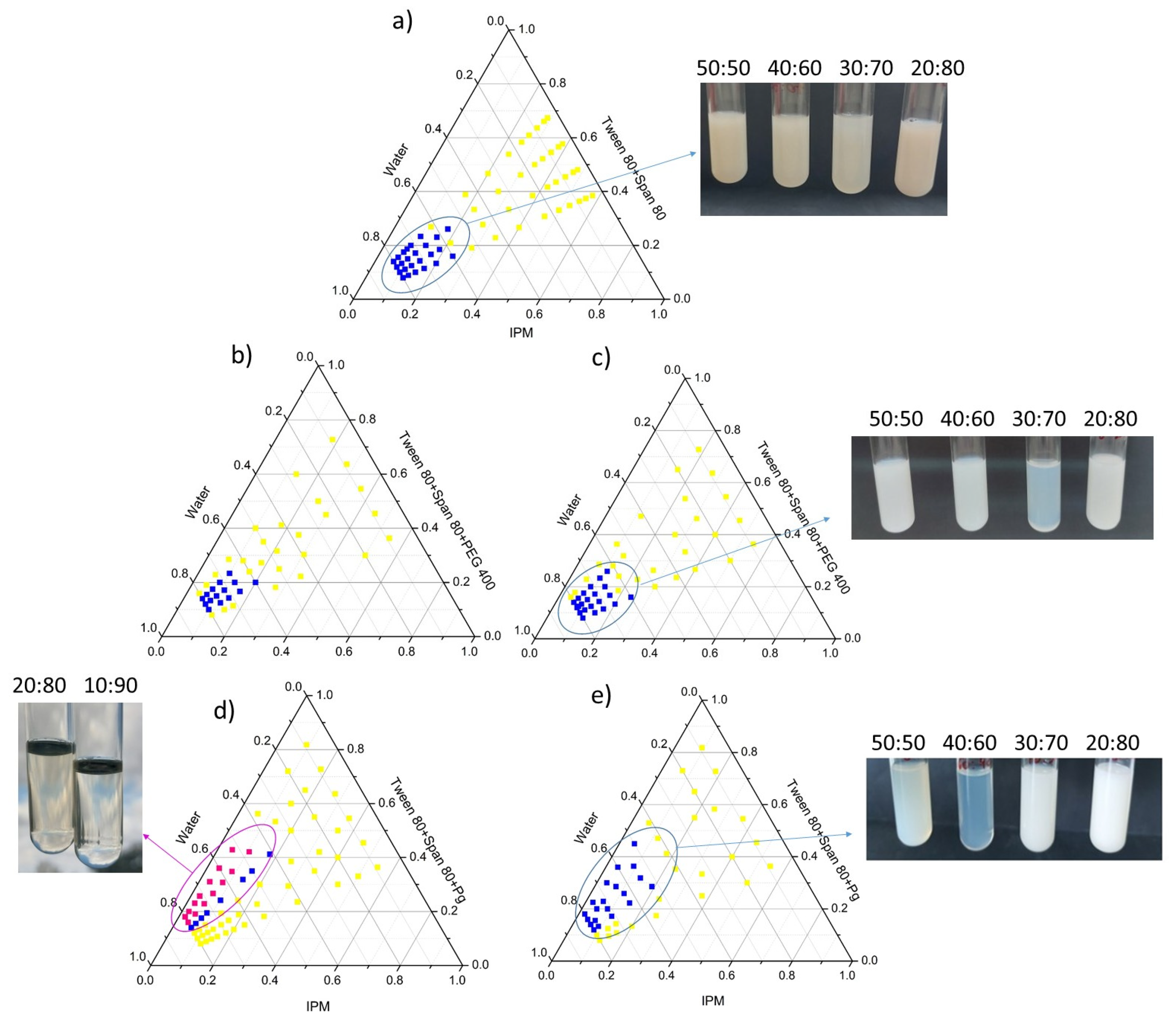

3.1.2. Phase Behavior of Nanoemulsions

3.1.3. Physico-Chemical Properties of Placebo and Ibuprofen-Loaded Nanoemulsions

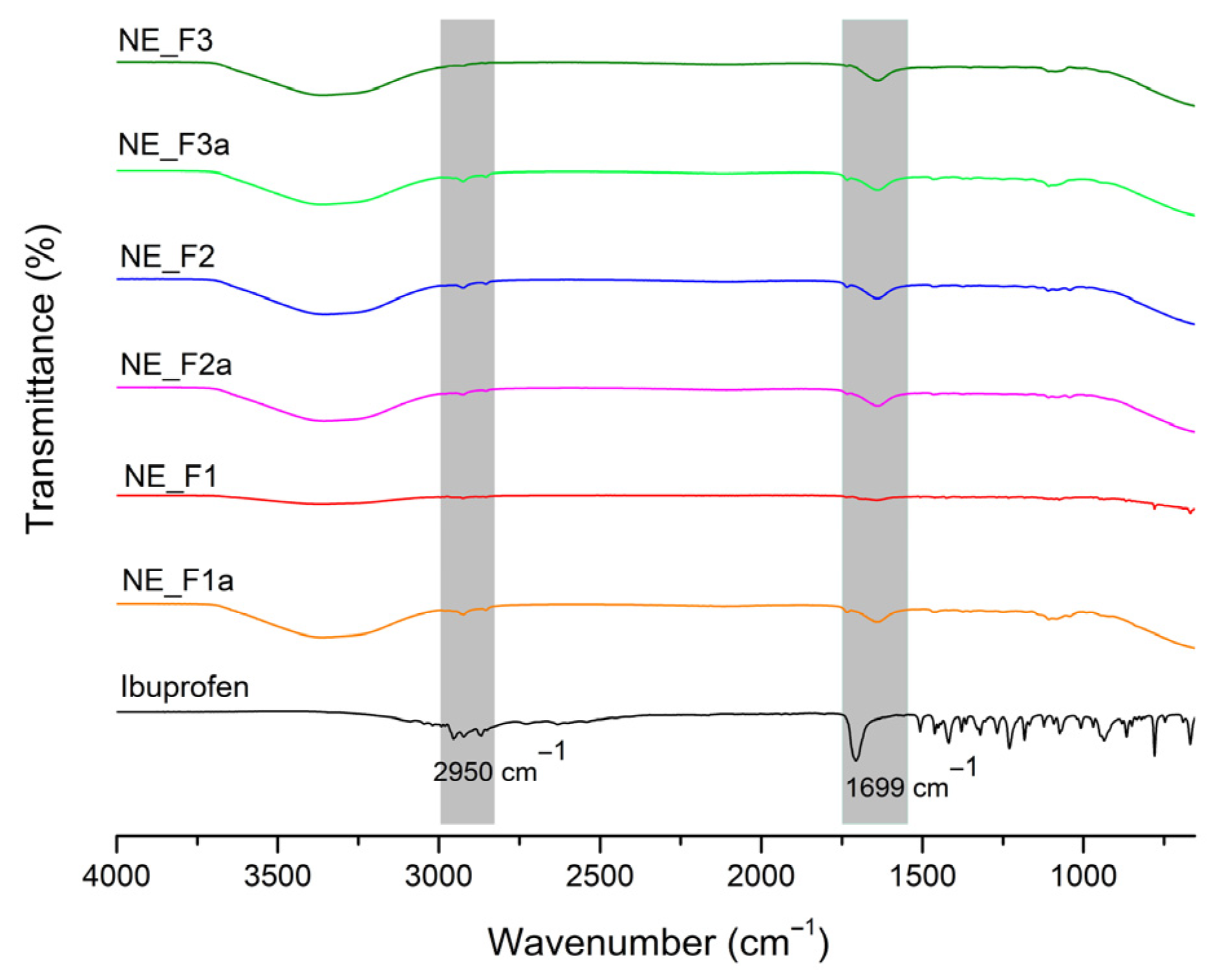

3.1.4. Investigation of Interfacial Organization

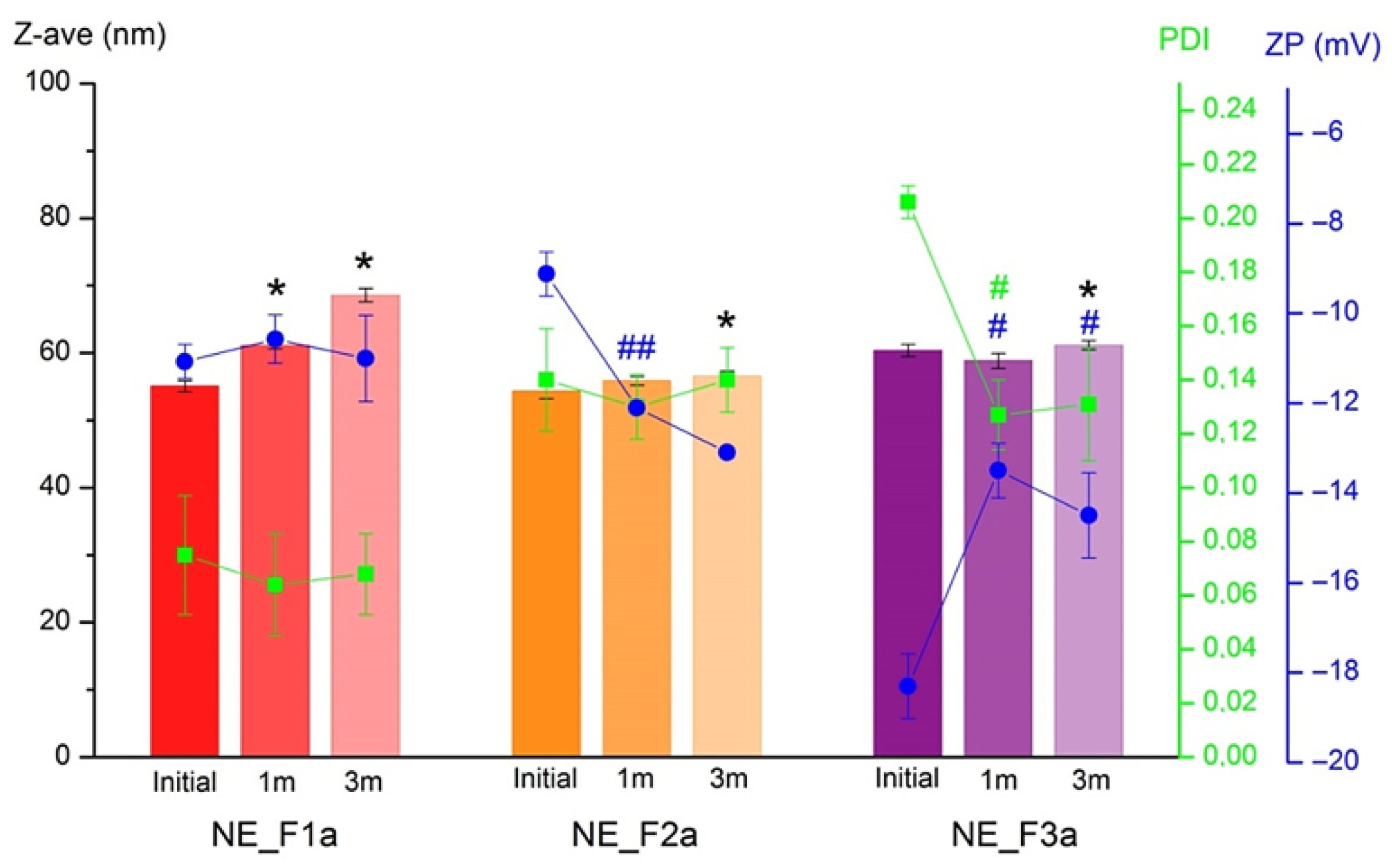

3.1.5. Stability Study

3.2. Multi-Technique Characterization of Nanoparticle Preservation upon Nanoemulsion-to-Nanogel Transformation

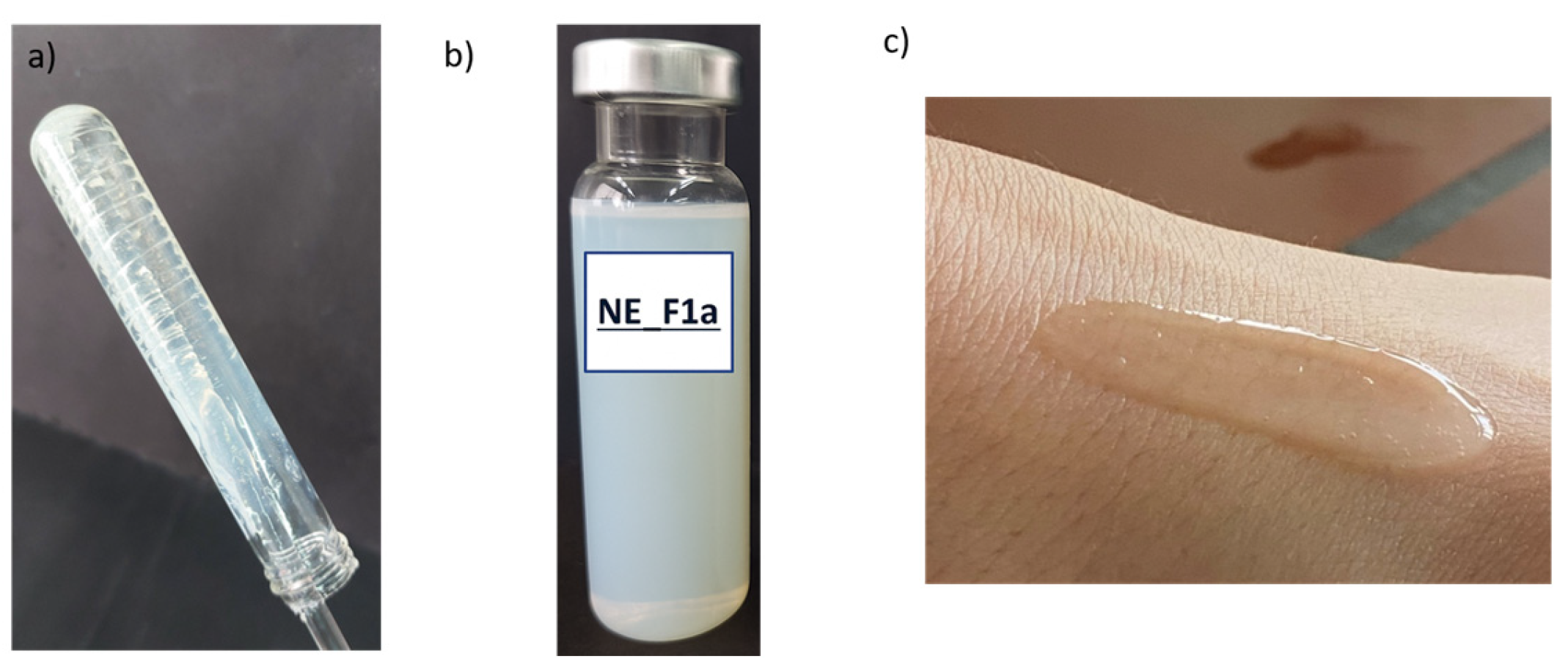

3.2.1. Physico-Chemical Properties of Nanoemulsion Gels

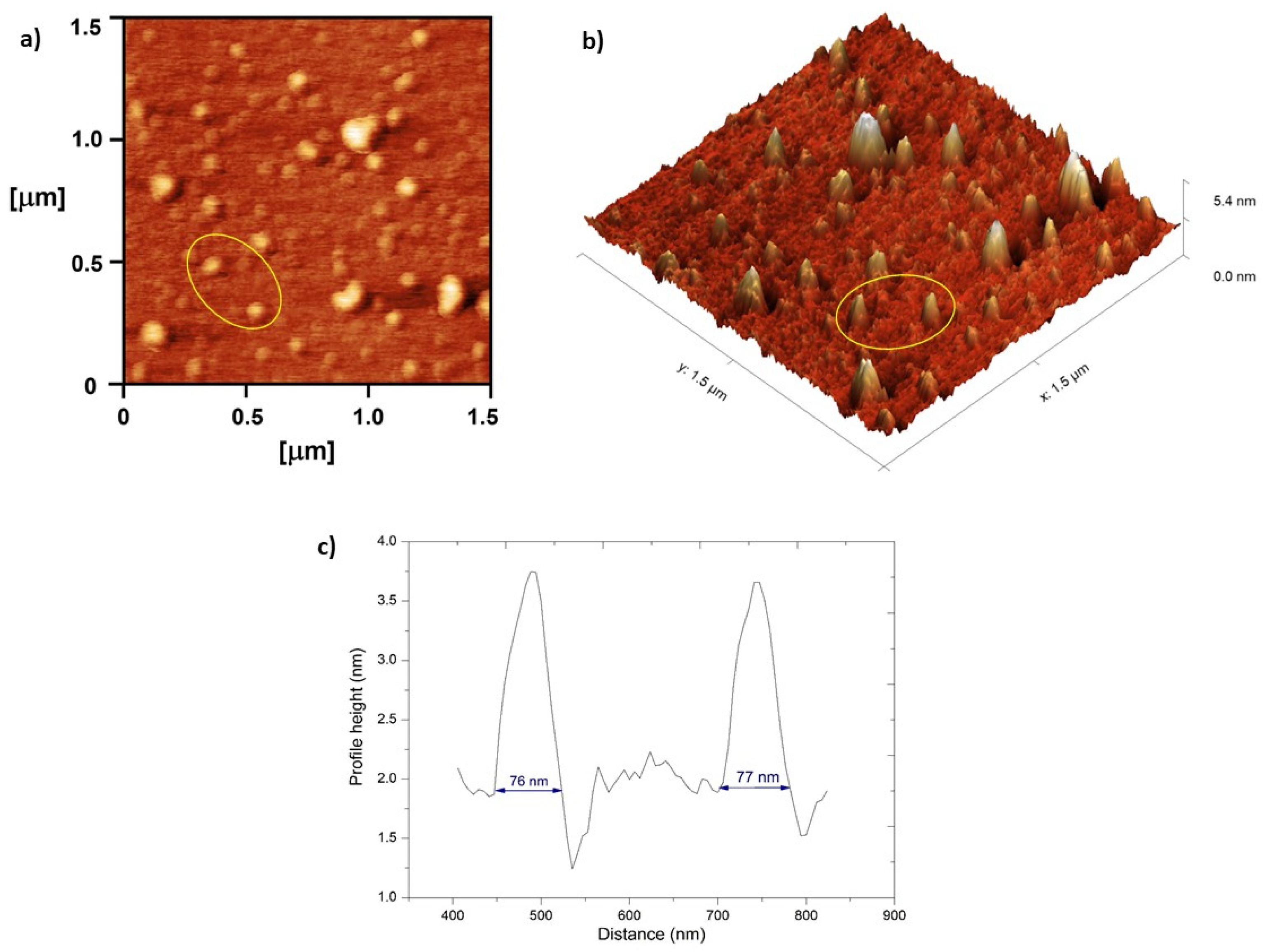

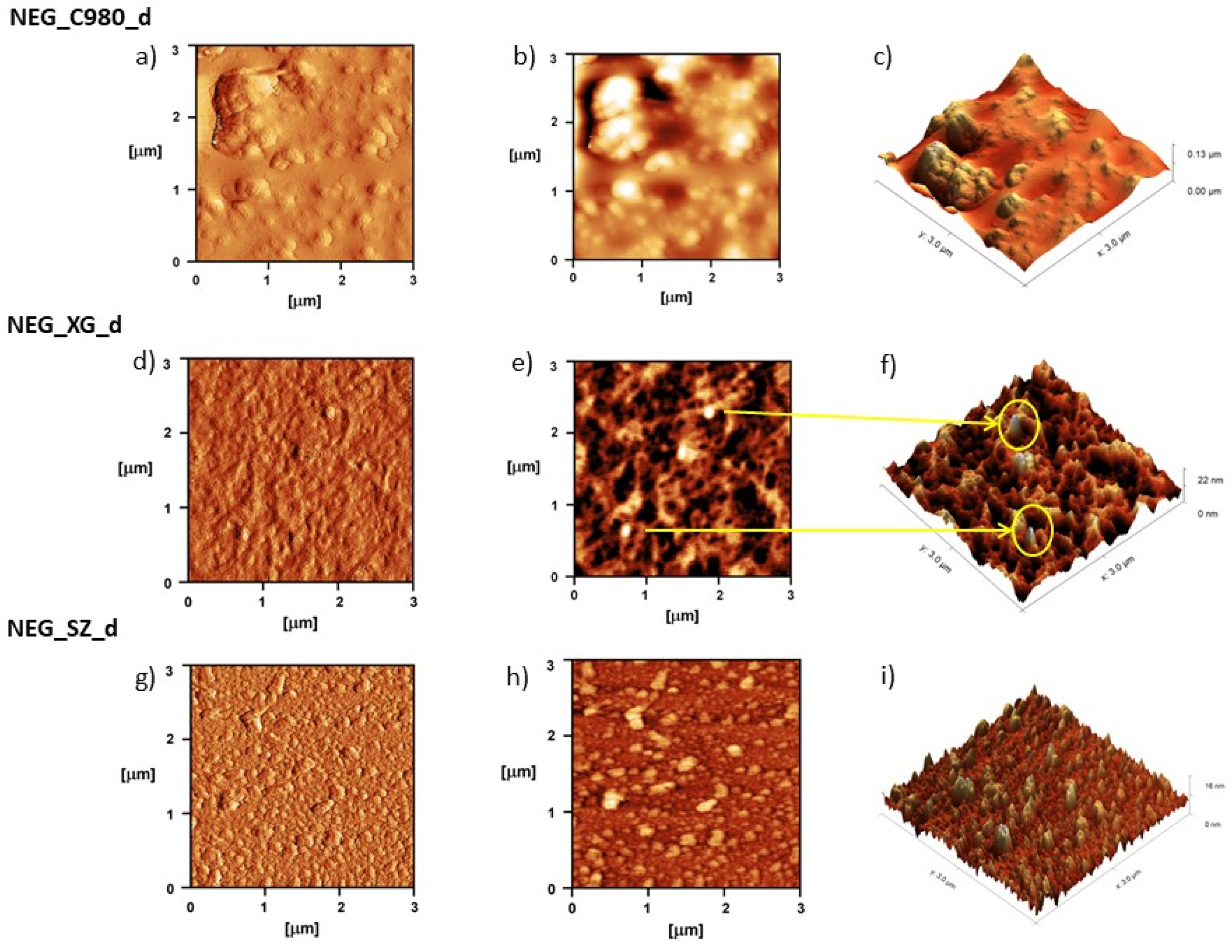

3.2.2. Visualization of Nanoemulsion and Nanoemulsion Gels’ Structure

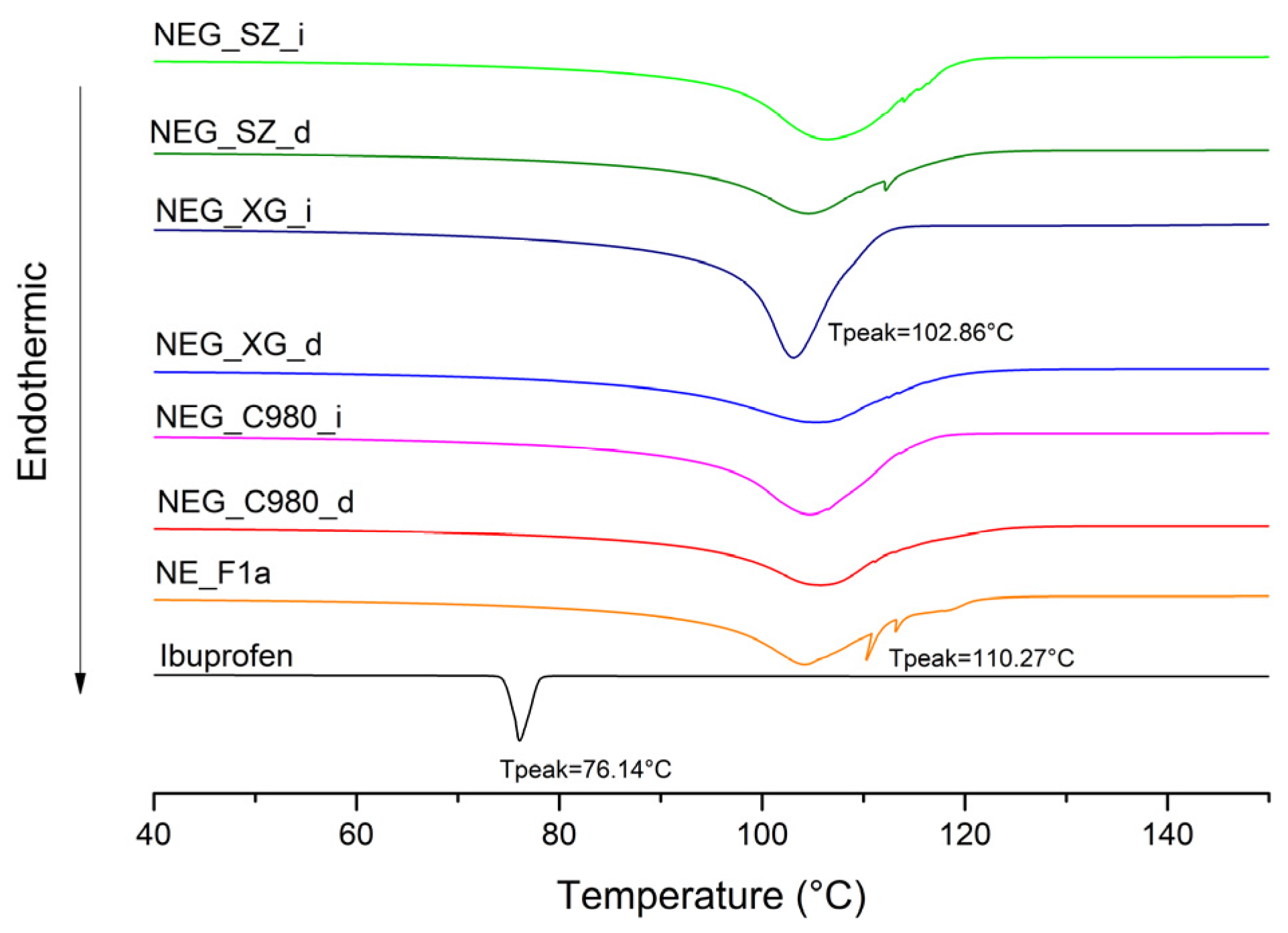

3.2.3. FT-IR and DSC Analysis of Nanoemulsion Gels

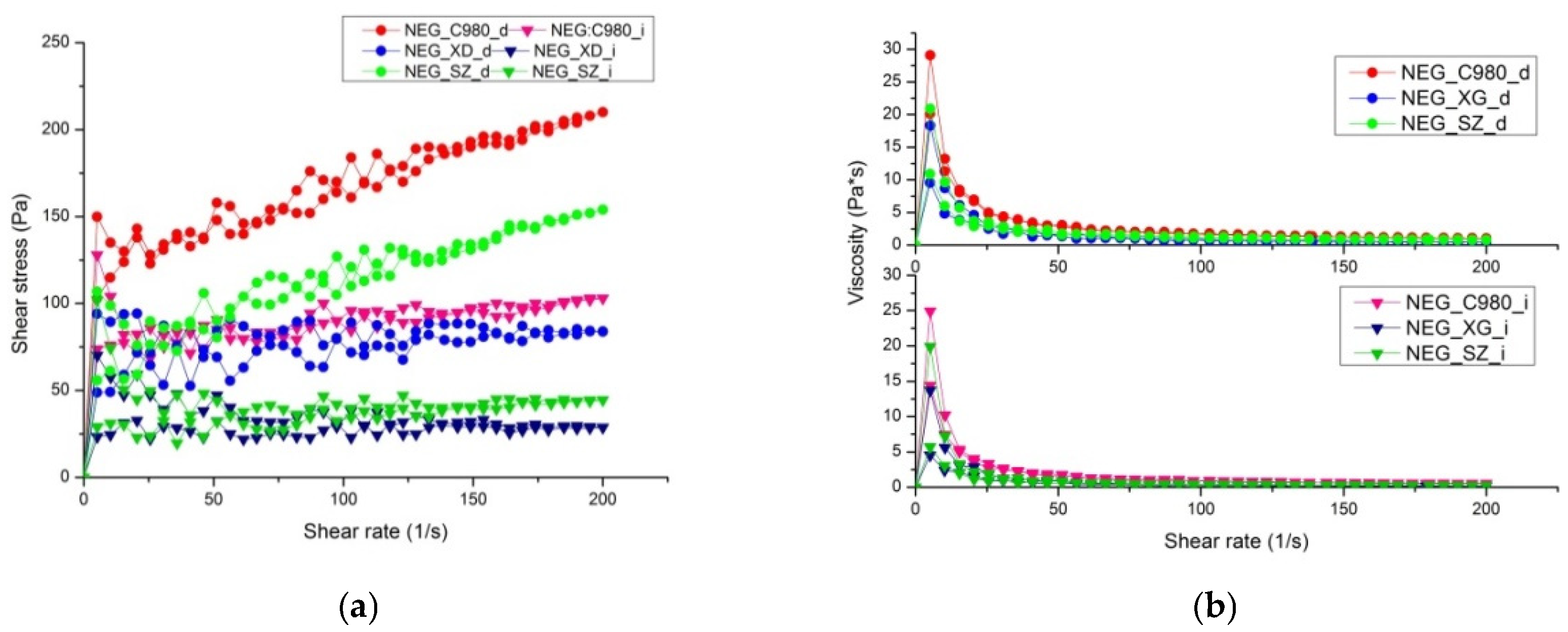

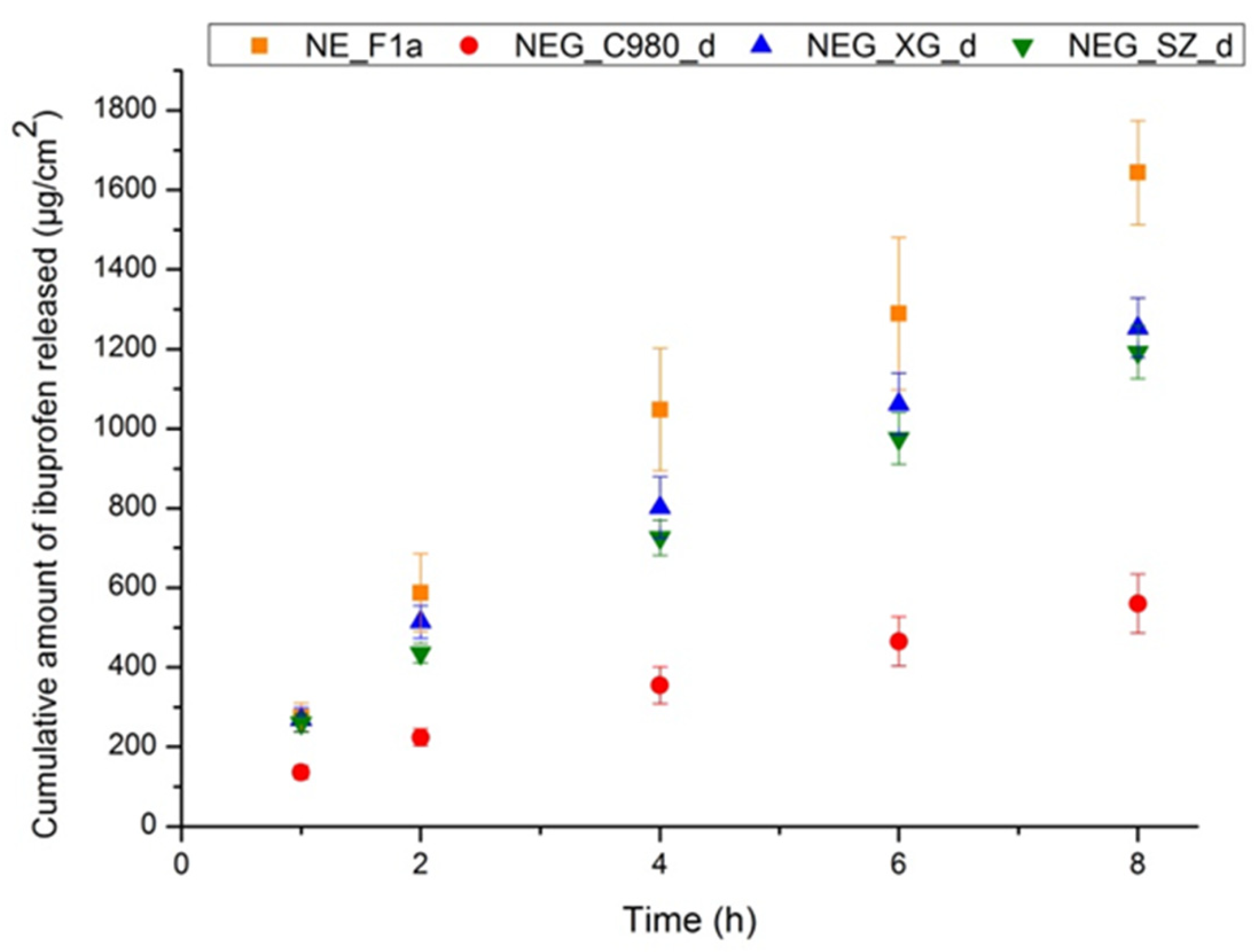

3.3. Integrating Rheological Characterization and Performance Testing into the Regulatory Translation of Innovative Formulations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 16-DSA | 16-doxylstearic acid |

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| 5-DSA | 5-doxylstearic acid |

| AFM | Atomic force micoscopy |

| DAD | Diode array detector |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| EC | Electrical conductivity |

| EPI | Emulsion phase inversion |

| EPR | Electron paramagnetic resonance |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FT-IR | Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy |

| HLB | Hydrophilic–lipophilic balance |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| HPMC | Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose |

| IPM | Isopropyl myristate |

| IVPT | in vitro permeation test |

| IVRT | in vitro release test |

| MCT | Medium-chain triglycerides |

| NaCMC | Sodium Carboxymethyl Cellulose |

| NE | Nanoemulsion |

| NEG | Nanoemulsion gel, nanoemulgel, nanogel |

| NSAID | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PDI | Polydispersity index |

| PEG 400 | Polyethylene glycol 400 |

| Pg | Propylene glycol |

| PIT | Phase inversion temperature |

| rpm | Revolutions per minute |

| S | Order degree |

| S/CoS | Surfactant/co-solvent ratio |

| SOR | Surfactant-to-oil ratio |

| Span 80 | Sorbitane oleate, Span® 80 |

| Tween 80 | Polysorbate 80, Tween® 80 |

| Z-ave | Average droplet size |

| ZP | Zeta potential |

| αN | Isotropic hyperfine coupling constant |

| τR | Rotational correlation time |

References

- Lunter, D.; Klang, V.; Eichner, A.; Savic, S.M.; Savic, S.; Lian, G.; Erdő, F. Progress in topical and transdermal drug delivery research—Focus on nanoformulations. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, M.; Tuberoso, C.I.G.; Pons, R.; García, M.T.; Morán, M.d.C.; Ferino, G.; Vassallo, A.; Martelli, G.; Caddeo, C. Phenolic Fingerprint, Bioactivity and Nanoformulation of Prunus spinosa L. Fruit Extract for Skin Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Wang, L.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hu, M.; Fang, H. The Current Status, Hotspots, and Development Trends of Nanoemulsions: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Review. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 2937–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, Y.; Meher, J.G.; Raval, K.; Khan, F.A.; Chaurasia, M.; Jain, N.K.; Chourasia, M.K. Nanoemulsion: Concepts, development and applications in drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2017, 252, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaiko, J.S.; McClements, D.J. Formation of food-grade nanoemulsions using low-energy preparation methods: A review of available methods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Bishnoi, R.S.; Shukla, A.K.; Jain, C.P. Techniques for formulation of nanoemulsion drug delivery system: A review. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 24, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, I.; Jasmin Lunter, D.; Randjelovic, D.; Zugic, A.; Tadic, V.; Markovic, B.; Cekic, N.; Zivkovic, L.; Topalovic, D.; Spremo-Potparevic, B.; et al. Curcumin-loaded low-energy nanoemulsions as a prototype of multifunctional vehicles for different administration routes: Physicochemical and in vitro peculiarities important for dermal application. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 550, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guan, X.; Zheng, C.; Wang, N.; Lu, H.; Huang, Z. New low-energy method for nanoemulsion formation: pH regulation based on fatty acid/amine complexes. Langmuir 2020, 36, 10082–10090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Badruddoza, A.Z.M.; Doyle, P.S. A general route for nanoemulsion synthesis using low-energy methods at constant temperature. Langmuir 2017, 33, 7118–7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostertag, F.; Weiss, J.; McClements, D.J. Low-energy formation of edible nanoemulsions: Factors influencing droplet size produced by emulsion phase inversion. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 388, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solans, C.; Solé, I. Nano-emulsions: Formation by low-energy methods. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 17, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, N.; Vandamme, T.F. The universality of low-energy nano-emulsification. Int. J. Pharm. 2009, 377, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidov-Pardo, G.; McClements, D.J. Nutraceutical delivery systems: Resveratrol encapsulation in grape seed oil nanoemulsions formed by spontaneous emulsification. Food Chem. 2015, 167, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolic, I.; Mitsou, E.; Pantelic, I.; Randjelovic, D.; Markovic, B.; Papadimitriou, V.; Xenakis, A.; Lunter, D.J.; Zugic, A.; Savic, S. Microstructure and biopharmaceutical performances of curcumin-loaded low-energy nanoemulsions containing eucalyptol and pinene: Terpenes’ role overcome penetration enhancement effect? Eur. J. Pharm. Sci 2020, 142, 105135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marhamati, M.; Ranjbar, G.; Rezaie, M. Effects of emulsifiers on the physicochemical stability of Oil-in-water Nanoemulsions: A critical review. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 340, 117218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potthast, H.; Dressman, J.B.; Junginger, H.E.; Midha, K.K.; Oeser, H.; Shah, V.P.; Vogelpoel, H.; Barends, D.M. Biowaiver monographs for immediate release solid oral dosage forms: Ibuprofen. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 94, 2121–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainsford, K.D. Ibuprofen: Pharmacology, efficacy and safety. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 17, 275–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derry, S.; Wiffen, P.J.; Kalso, E.A.; Bell, R.F.; Aldington, D.; Phillips, T.; Gaskell, H.; Moore, R.A. Topical analgesics for acute and chronic pain in adults—An overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, CD008609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, M.H.; Foudah, A.I.; Aodah, A.H.; Alkholifi, F.K.; Salkini, M.A.; Alam, A. Caraway Nanoemulsion gel: A potential antibacterial treatment against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Gels 2023, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, H.; Gorain, B.; Pandey, M.; Chatterjee, L.A.; Sengupta, P.; Das, A.; Molugulu, N.; Kesharwani, P. Recent update on nanoemulgel as topical drug delivery system. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 1736–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, V.K.; Mishra, N.; Yadav, K.S.; Yadav, N.P. Nanoemulsion as pharmaceutical carrier for dermal and transdermal drug delivery: Formulation development, stability issues, basic considerations and applications. J. Control. Release 2018, 270, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, D.K.; Kumar, B.; Saeedan, A.S.; Ansari, M.N. An overview of nanoemulgels for bioavailability enhancement in inflammatory conditions via topical delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donthi, M.R.; Munnangi, S.R.; Krishna, K.V.; Saha, R.N.; Singhvi, G.; Dubey, S.K. Nanoemulgel: A novel nano carrier as a tool for topical drug delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, I.F.; Rebouças, L.M.; de Goes Sampaio, C.; Ricardo, N.M.P.S.; Santos, E.M.A.; da Silva, A.L.F. Nanoemulgel Based on Guar Gum and Pluronic® F127 Containing Encapsulated Hesperidin with Antioxidant Potential. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2022, 5, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.G.; Lee, M.Y.; Cha, J.M.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, S.C.; Kim, J.; Hwang, Y.S.; Bae, H. Nanogels derived from fish gelatin: Application to drug delivery system. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaro-Rodríguez, M.C.; Prieto, P.; García, M.C.; Martín-Piñero, M.J.; Muñoz, J. Influence of nanoemulsion/gum ratio on droplet size distribution, rheology and physical stability of nanoemulgels containing inulin and omega-3 fatty acids. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 6397–6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ma, X.; Zong, S.; Su, Y.; Su, R.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, Y. The prescription design and key properties of nasal gel for CNS drug delivery: A review. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 192, 106623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubrizol Advanced Materials, Inc. Neutralizing Carbopol®* and Pemulen™* Polymers in Aqueous and Hydroalcoholic Systems; Technical Data Sheet TDS-237 (Previous Editions: January 2002/10 July 2008); Lubrizol: Cleveland, OH, USA, 16 September 2009; Available online: https://www.lubrizol.com/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Kumara, P.; Prakash, S.C.; Lokesh, P.; Manral, K. Viscoelastic properties and rheological characterization of carbomers. Int. J. Latest Res. Eng. Technol. 2015, 1, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Reformulating Drug Products that Contain Carbomers Manufactured with Benzene: Final Guidance (December 2023); Docket No. FDA-2023-D-5408; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research: Silver Spring, MD, USA. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/reformulating-drug-products-contain-carbomers-manufactured-benzene (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Mishra, B.; Sahoo, S.K.; Sahoo, S. Liranaftate loaded Xanthan gum based hydrogel for topical delivery: Physical properties and ex-vivo permeability. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 1717–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppic. Sepimax Zen—Product Page. Available online: https://www.seppic.com/product/sepimax-zen (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Mayer, S.; Weiss, J.; McClements, D.J. Vitamin E-enriched nanoemulsions formed by emulsion phase inversion: Factors influencing droplet size and stability. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 402, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaya, M.; Rotliwala, Y.C. Nanoemulsions: A review on low energy formulation methods, characterization, applications and optimization technique. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanzad, F.; Crombie, G.; Innes, R.; Sajjadi, S. Catastrophic phase inversion via formation of multiple emulsions: A prerequisite for formation of fine emulsions. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2009, 87, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, H.K.; Peh, K.K. Identification of phases of various oil, surfactant/co-surfactants and water system by ternary phase diagram. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2014, 71, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jacob, S.; Kather, F.S.; Boddu, S.H.S.; Shah, J.; Nair, A.B. Innovations in Nanoemulsion Technology: Enhancing Drug Delivery for Oral, Parenteral, and Ophthalmic Applications. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szumała, P.; Kaplinska, J.; Makurat-Kasprolewicz, B.; Mania, S. Microemulsion delivery systems with low surfactant concentrations: Optimization of structure and properties by glycol cosurfactants. Mol. Pharm. 2023, 20, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, A.H.; Fang, Y.; McClements, D.J. Fabrication of vitamin E-enriched nanoemulsions: Factors affecting particle size using spontaneous emulsification. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 391, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, M.; Ujjwal, R.R.; Vasdev, N.; Flora, S.J.S.; Shukla, R. Optimization of surfactant-and cosurfactant-aided pine oil nanoemulsions by isothermal low-energy methods for anticholinesterase activity. ACS Omega 2020, 6, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, T.; Đoković, J.B.; Nikolić, I.; Mitrović, J.R.; Pantelić, I.; Savić, S.D.; Savić, M.M. Parenteral lipid-based nanoparticles for CNS disorders: Integrating various facets of preclinical evaluation towards more effective clinical translation. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembek, M.; Bocian, S.; Buszewski, B. Solvent Influence on Zeta Potential of Stationary Phase-Mobile Phase Interface. Molecules 2022, 27, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeef, A.; Box, K.J.; Comer, J.E.A.; Gilges, M.; Hadley, M.; Hibbert, C.; Patterson, W.; Tam, K.Y. Solubility of ibuprofen in water–acetonitrile mixtures by pH-metric method: pKa determination. J. Pharm. Sci. 1999, 88, 1253–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogianni, E.P.; Sklaviadis, L.; Nika, S.; Theochari, I.; Dimitreli, G.; Georgiou, D.; Papadimitriou, V. Effect of oleic acid on the properties of protein adsorbed layers at water/oil interfaces: An EPR study combined with dynamic interfacial tension measurements. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 158, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadimitriou, V.; Pispas, S.; Syriou, S.; Pournara, A.; Zoumpanioti, M.; Sotiroudis, T.G.; Xenakis, A. Biocompatible microemulsions based on limonene: Formulation, structure, and applications. Langmuir 2008, 24, 3380–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demisli, S.; Mitsou, E.; Pletsa, V.; Xenakis, A.; Papadimitriou, V. Development and study of nanoemulsions and nanoemulsion-based hydrogels for the encapsulation of lipophilic compounds. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramukutty, S.; Ramachandran, E.J.C.R. Growth, spectral and thermal studies of ibuprofen crystals. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2012, 47, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, P.S.; Clarke, G.S.; Kazarian, S.G. Application of FTIR spectroscopic imaging to study the effects of modifying the pH microenvironment on the dissolution of ibuprofen from HPMC matrices. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 100, 4745–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerdkanchanaporn, S. A thermal analysis study of ibuprofen and starch mixtures using simultaneous TG–DTA. Thermochim. Acta 1999, 340, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutradhar, K.B.; Amin, M.L. Nanoemulsions: Increasing possibilities in drug delivery. Eur. J. Nanomed. 2013, 5, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, G.; Witczak, M.; Kuterasiński, Ł. Structure effects on swelling properties of hydrogels based on sodium alginate and acrylic polymers. Molecules 2024, 29, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantelić, I.; Ilić, T.; Nikolić, I.; Savić, S. Self-assembled carriers as drug delivery systems: Current characterization challenges and future prospects. Arh. Farm. 2023, 73, 404–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadav, M.; Pooja, D.; Adams, D.J.; Kulhari, H. Advances in xanthan gum-based systems for the delivery of therapeutic agents. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobra, K.; Wong, S.Y.; Mazumder, M.A.J.; Li, X.; Arafat, M.T. Xanthan and gum acacia modified olive oil based nanoemulsion as a controlled delivery vehicle for topical formulations. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eid, A.M.; El-Enshasy, H.A.; Aziz, R.; Elmarzugi, N.A. Preparation, characterization and anti-inflammatory activity of Swietenia macrophylla nanoemulgel. J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 2014, 5, 1000190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippov, S.K.; Khusnutdinov, R.; Murmiliuk, A.; Inam, W.; Zakharova, L.Y.; Zhang, H.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V. Dynamic light scattering and transmission electron microscopy in drug delivery: A roadmap for correct characterization of nanoparticles and interpretation of results. Mater. Horiz. 2023, 10, 5354–5370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupikowska-Stobba, B.; Domagała, J.; Kasprzak, M.M. Critical Review of Techniques for Food Emulsion Characterization. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gledovic, A.; Janosevic Lezaic, A.; Nikolic, I.; Tasic-Kostov, M.; Antic-Stankovic, J.; Krstonosic, V.; Randjelovic, D.; Bozic, D.; Ilic, D.; Tamburic, S.; et al. Polyglycerol Ester-Based Low Energy Nanoemulsions with Red Raspberry Seed Oil and Fruit Extracts: Formulation Development toward Effective In Vitro/In Vivo Bioperformance. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMA. Draft Guideline on Quality and Equivalence of Topical Products; EMA/CHMP/QWP/708282/2018; European Medicines Agency: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/draft-guideline-quality-equivalence-topical-products_en.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Chiarentin, L.; Cardoso, C.; Miranda, M.; Vitorino, C. Rheology of complex topical formulations: An analytical quality by design approach to method optimization and validation. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, L.; Mazál, J.; Petz, R.; Klang, V.; Valenta, C. The role of viscosity on skin penetration from cellulose ether-based hydrogels. Skin Res. Technol. 2019, 25, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, F.C.; De Lima, J.A.; Da Silva, C.R.; Benvegnú, D.; Ferreira, J.; Burger, M.E.; Beck, R.C.; Rolim, C.M.; Rocha, M.I.; Da Veiga, M.L.; et al. Hydrogels Containing Nanocapsules and Nanoemulsions of Tea Tree Oil Provide Antiedematogenic Effect and Improved Skin Wound Healing. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yin, D.; Huang, T.; Zhang, H.; Yue, M.; Huang, X. Rheological Properties of Weak Gel System Cross-Linked from Chromium Acetate and Polyacrylamide and Its Application in Enhanced Oil Recovery After Polymer Flooding for Heterogeneous Reservoir. Gels 2024, 10, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghica, M.V.; Hîrjău, M.; Lupuleasa, D.; Dinu-Pîrvu, C.E. Flow and thixotropic parameters for rheological characterization of hydrogels. Molecules 2016, 21, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.; Cardoso, C.; Vitorino, C. Fast screening methods for the analysis of topical drug products. Processes 2020, 8, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantini, A.; Padula, C.; Nicoli, S.; Pescina, S.; Santi, P. The role of vehicle metamorphosis on triamcinolone acetonide delivery to the skin from microemulsions. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 565, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.P.; Miron, D.S.; Rădulescu, F.Ș.; Cardot, J.M.; Maibach, H.I. In vitro release test (IVRT): Principles and applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 626, 122159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsikó, S.; Csányi, E.; Kovács, A.; Budai-Szűcs, M.; Gácsi, A.; Berkó, S. Methods to evaluate skin penetration in vitro. Sci. Pharm. 2019, 87, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, L.; Atif, R.; Eldeen, T.S.; Yahya, I.; Omara, A.; Eltayeb, M. Study the using of nanoparticles as drug delivery system based on mathematical models for controlled release. Int. J. Latest Trends Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. 2019, 8, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

| Excipient | Ibuprofen Solubility (mg/mL) |

|---|---|

| IPM | 65.94 ± 0.51 |

| MCT | 42.21 ± 0.28 |

| Decyl oleate | 38.12 ± 0.11 |

| Octyldodecanol | 43.41 ± 0.29 |

| Tween 80 | 203.65 ± 1.32 |

| Tween 60 | 166.63 ± 0.95 |

| Ethanol | 337.78 ± 0.81 |

| Pg | 189.41 ± 0.51 |

| PEG 400 | 239.75 ± 0.85 |

| Formulation | Composition (% w/w) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ibuprofen | IPM | Tween 80/Span 80 (3:1) | PEG 400 | Pg | Water Up To | ||

| Placebo | NE_F1 | / | 10 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 100 |

| NE_F2 | / | 10 | 10 | / | 5 | 100 | |

| NE_F3 | / | 10 | 10 | 5 | / | 100 | |

| Active | NE_F1a | 2 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 100 |

| NE_F2a | 2 | 10 | 10 | / | 5 | 100 | |

| NE_F3a | 2 | 10 | 10 | 5 | / | 100 | |

| Formulation | Z-Ave (nm) | PDI | Zeta Potential (mV) | pH | Conductivity (µS/cm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | NE_F1 | 80.56 ± 0.41 c | 0.251 ± 0.016 | −14.10 ± 1.20 a | 6.00 ± 0.03 | 135.23 ± 0.42 c |

| NE_F2 | 130.00 ± 0.51 c | 0.184 ± 0.021 | −26.70 ± 0.98 | 6.42 ± 0.02 | 128.13 ± 0.67 c | |

| NE_F3 | 108.40 ± 0.45 c | 0.257 ± 0.003 a | −25.80 ± 0.70 | 5.84 ± 0.04 | 152.37 ± 0.78 c | |

| Active | NE_F1a | 55.07 ± 0.82 f | 0.075 ± 0.022 f | −11.07 ± 0.38 f | 5.11 ± 0.01 d | 166.35 ± 0.91 f |

| NE_F2a | 54.35 ± 1.16 f | 0.140 ± 0.019 f | −9.12 ± 0.49 f | 5.13 ± 0.05 f | 94.10 ± 0.26 f | |

| NE_F3a | 60.38 ± 0.92 f | 0.206 ± 0.006 f | −18.30 ± 0.72 f | 4.96 ±0.03 f | 113.40 ± 0.03 f | |

| Spin Probe | EPR Parameters | NE_F1 | NE_F1a | NE_F2 | NE_F2a | NE_F3 | NE_F3a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-DSA | τR (ns) | 2.11 ± 0.03 | 2.06 ± 0.06 | 2.13 ± 0.10 | 1.82 ± 0.08 | 2.13 ± 0.09 | 1.90 ± 0.06 |

| S | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | |

| αN (×10−4 T) | 13.98 ± 0.12 | 13.75 ± 0.43 | 13.15 ± 0.19 | 14.02 ± 0.1 | 13.71 ± 0.37 | 14.01 ± 0.15 | |

| 16-DSA | τR (ns) | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.06 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 0.38 ± 0.03 |

| S | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | |

| αN (×10−4 T) | 14.72 ± 0.08 | 14.69 ± 0.08 | 14.66 ± 0.10 | 14.72 ± 0.06 | 14.64 ± 0.01 | 14.76 ± 0.06 |

| Gelling Agent | NEG Sample | Z-ave (nm) | PDI | ZP (mV) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbopol 980 | NEG_C980_d | 94.03 ± 0.63 c,f | 0.222 ± 0.008 b,f | −25.4 ± 2.9 e | 5.71 ± 0.01 c,f |

| NEG_C980_i | 63.91 ± 0.37 c,f | 0.164 ± 0.021 b,e | −27.9 ± 1.3 f | 5.53 ± 0.01 c,f | |

| Xanthan gum | NEG_XG_d | 67.73 ± 1.15 f | 0.195 ± 0.007 c,e | −20.6 ± 2.1 e | 5.46 ± 0.03 c,f |

| NEG_XG_i | 65.54 ± 1.35 f | 0.225 ± 0.008 c,f | −21.1 ± 0.9 f | 5.65 ± 0.01 c,f | |

| Polyacrylate Crosspolymer-6 (Sepimax Zen) | NEG_SZ_d | 71.63 ± 1.13 c,f | 0.134 ± 0.007 d | −30.5 ± 0.9 f | 5.72 ± 0.02 f |

| NEG_SZ_i | 60.65 ± 0.84 c,f | 0.126 ± 0.008 d | −26.3 ± 2.1 e | 5.65 ± 0.05 f |

| Formulations | Maximal Apparent Viscosity (Pa·s) | Minimal Apparent Viscosity (Pa·s) | Hysteresis Area (Pa/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEG_C980_d | 29.13 ± 1.55 | 1.04 ± 0.09 | 1322.64 |

| NEG_XG_d | 18.37 ± 2.31 | 0.42 ± 0.05 | 2483.91 |

| NEG_SZ_d | 20.87 ± 3.44 | 0.77 ± 0.04 | 1507.88 |

| NEG_C980_i | 24.97 ± 2.31 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 1854.44 |

| NEG_XG_i | 13.73 ± 1.74 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 1923.80 |

| NEG_SZ_i | 19.86 ± 1.94 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 2036.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tošić, A.; Randjelović, D.; Ivković, B.; Gledović, A.; Stanković, T.; Đoković, J.; Papadimitriou, V.; Ilić, T.; Savić, S.D.; Pantelić, I. Interfacial Molecular Interactions as Determinants of Nanostructural Preservation in Ibuprofen-Loaded Nanoemulsions and Nanoemulsion Gels. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121532

Tošić A, Randjelović D, Ivković B, Gledović A, Stanković T, Đoković J, Papadimitriou V, Ilić T, Savić SD, Pantelić I. Interfacial Molecular Interactions as Determinants of Nanostructural Preservation in Ibuprofen-Loaded Nanoemulsions and Nanoemulsion Gels. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121532

Chicago/Turabian StyleTošić, Anđela, Danijela Randjelović, Branka Ivković, Ana Gledović, Tijana Stanković, Jelena Đoković, Vassiliki Papadimitriou, Tanja Ilić, Snežana D. Savić, and Ivana Pantelić. 2025. "Interfacial Molecular Interactions as Determinants of Nanostructural Preservation in Ibuprofen-Loaded Nanoemulsions and Nanoemulsion Gels" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121532

APA StyleTošić, A., Randjelović, D., Ivković, B., Gledović, A., Stanković, T., Đoković, J., Papadimitriou, V., Ilić, T., Savić, S. D., & Pantelić, I. (2025). Interfacial Molecular Interactions as Determinants of Nanostructural Preservation in Ibuprofen-Loaded Nanoemulsions and Nanoemulsion Gels. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121532