Optical Density-Based Methods in Phage Biology: Titering, Lysis Timing, Host Range, and Phage-Resistance Evolution

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Measuring phage lysis timing (Section 3);

- Characterizing the phenomenon of lysis inhibition (Section 4);

- Detecting lysis from without as well as resistance to lysis from without (Section 6);

- Assessing phage ability to impact different bacterial strains (Section 7); and

- Gauging phage suppression of bacterial evolution of phage resistance (Section 8).

- All involve the addition of some quantity of phages to a broth culture containing some concentration of planktonic bacterial cells. Each section addresses both methodology and critical limitations of these approaches.

2. Most Probable Number Method (MPN)

2.1. MPN Method

2.2. MPN Cautions

…if the adsorption is poor or phage multiplication slow, lysis may occur only when a considerable number of phage particles are inoculated, and so the phage population will be grossly underestimated. In such cases, the estimate can be improved by testing for presence of phage in all tubes in which lysis failed.

- If a single phage is thus unable to lyse a bacteria-seeded broth tube, then there is a need to start with fewer bacteria. It is inconvenient, however, to check for phage presence in all unlysed tubes. Consequently, the possibility that it may require more than one starting phage to result in complete lysis of a culture should be first explored if relying on MPN methods for phage titering. See Section 2.4 for additional consideration of this concern.

- Minimal turbidity indicates phage-induced culture-wide bacterial lysis;

- Failure of a culture to lyse despite phage presence (a false negative due to insufficient phage antibacterial virulence, but see also Section 4); and

- Occurrence of culture-wide bacterial lysis that is followed by growth of phage-resistant bacterial mutants (also a false negative result; Section 8).

- Note, though, that it is possible to mitigate especially this latter issue by using kinetic rather than endpoint analyses.

2.3. Kinetic vs. Endpoint Analysis

2.4. Appelmans’ Method

A serial (10-fold sequential) dilution of a phage stock is required. …bacterial suspension should be added to all ten tubes … Evaluation of the results should be performed by comparing transparency of all the 12 tubes in the row. Culture control should become turbid demonstrating growth of the bacteria, while the media control should remain transparent, demonstrating sterility of the tubes and their content. The titer of test bacteriophage is estimated by the last dilution which remains transparent (this means that lyses of the bacterial suspension in this tube still occurs). The titer determined by Appelmans [60] is expressed by negative [log] figures corresponding to the dilution.

2.5. Consideration of Bacterial Initial Physiological State

Starter cultures may be initiated with a single colony and grown overnight or longer under whatever conditions the bacteria favor. Such cultures normally enter stationary phase, and after dilution they will lag for an irreproducible period of time before resuming growth. Therefore, they need to be diluted at least 100-fold and go through several divisions to ensure that all cells are in the same growth phase at the time of infection. An alternative approach works well with bacteria that do not lose viability upon rapid chilling: a starter culture grown to mid-log phase is immediately chilled in an ice bath and kept cold. Such cultures need only a 20-fold dilution for regrowth the next day, and the cells usually resume growth in a more reproducible manner than when stationary starter cultures are used.

- For the sake of temporal consistency and physiological reproducibility, experiments should thus be initiated with bacteria that have been grown to a mid-log phase physiology, unless it is phage infection of other bacterial physiological states that are being studied.

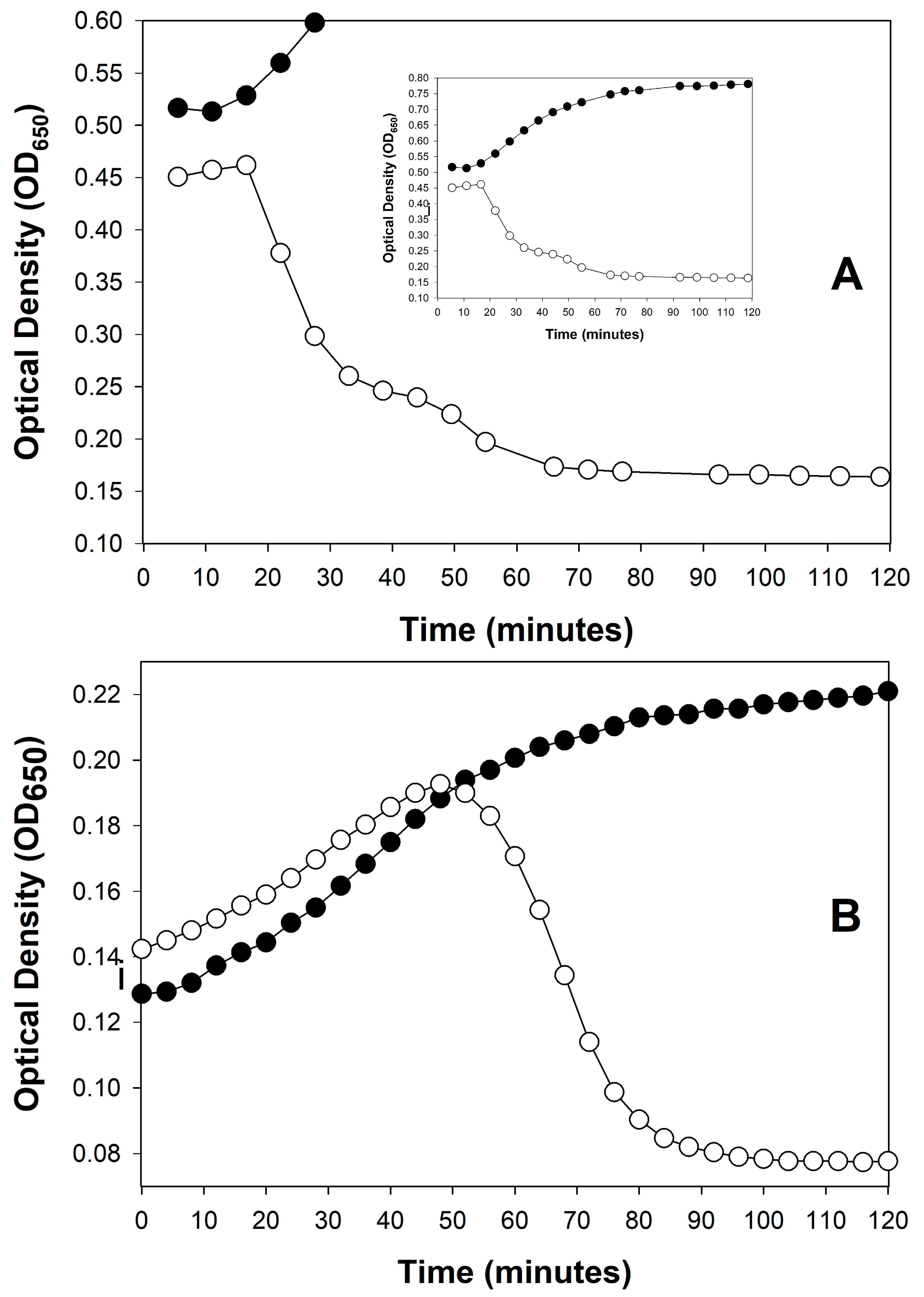

3. Estimation of Phage Life-History Characteristics

3.1. Inferring Lysis Timing Information

3.2. Inferring Other Phage Life-History Information

3.3. Multiplicity of Infection During Optical Density-Based Latent Period Determination

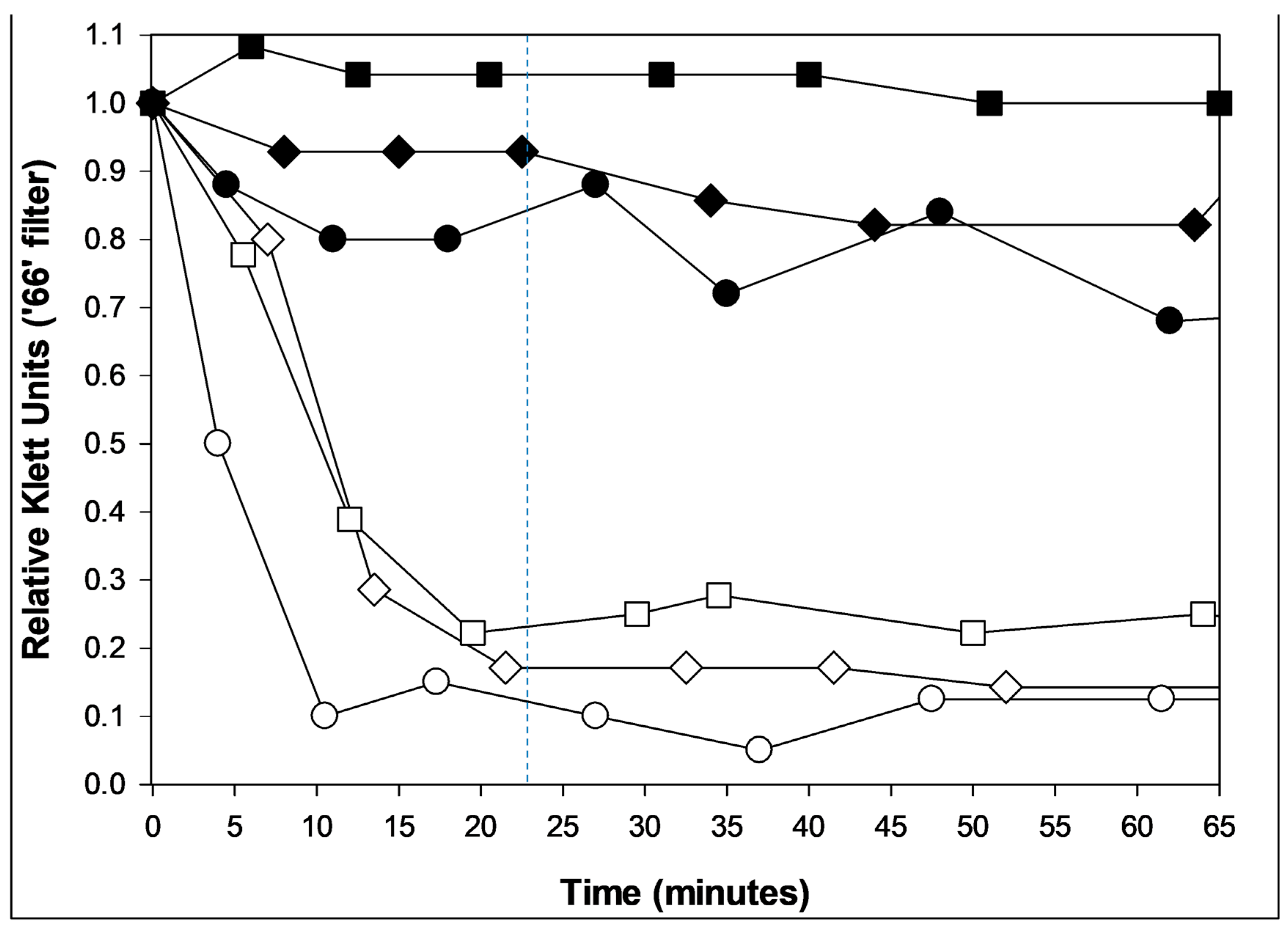

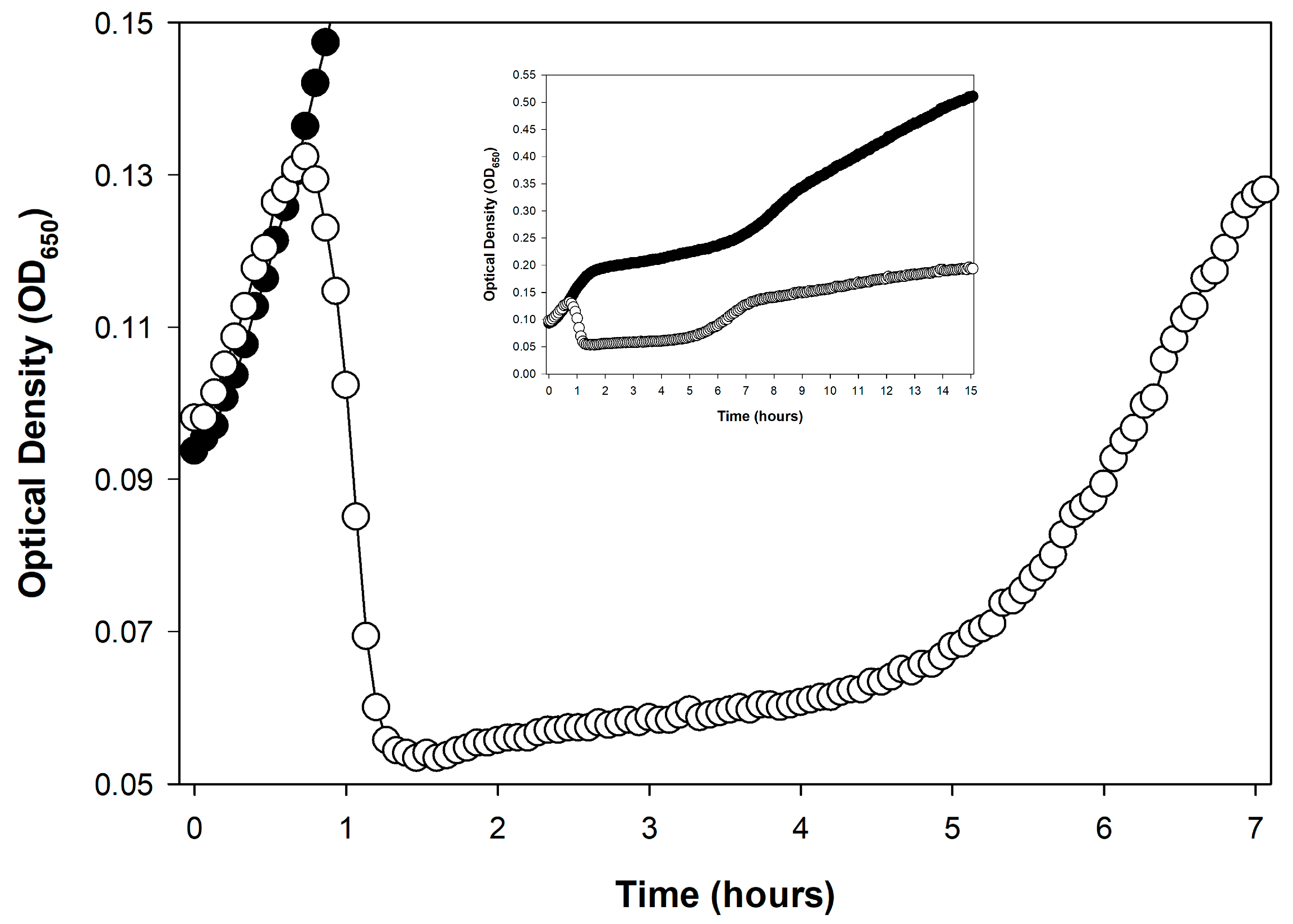

4. Lysis Inhibition as a Lysis Profile Complicating Factor

4.1. What Is Lysis Inhibition?

4.2. Earlier vs. Later Lysis-Inhibition Induction

4.3. Not an Issue for All Phages

4.4. Preventing the Lysis Inhibition Complication

4.4.1. Preventing Lysis Inhibition Early

4.4.2. Preventing Lysis Inhibition Later

4.4.3. Easier Approach That Needs More Testing

5. Titering Phages Based on Kinetic Optical Density Measurements

- Calibration requirements: The assay requires prior generation of calibration curves for every phage genotype to be assayed, representing a substantial upfront investment.

- Time savings uncertain: Though a primary utility of the KOTE approach is saving time in phage titer determinations, that time advantage can be lost given optimization of plaque-based titer determinations [132].

- Greater equipment requirements: Though KOTE assays can be less materials intensive, they are more equipment intensive, requiring access if they are going to be conveniently done to what generally are somewhat expensive incubating and shaking kinetic microtiter plate readers.

- Notwithstanding these concerns, KOTE assays could be useful to the extent that future phage titer determinations become fully automated—perhaps in combination with localized, fully automated phage-production platforms to support phage therapy use [133].

6. Lysis from Without and Resistance to Lysis from Without

6.1. Optical Observation of Lysis from Without

6.2. Additional Lysis-from-Without Caution

6.3. Non-Optical Assay for Resistance to Lysis from Without

7. Phage Host-Range Determination

7.1. Optical Density-Based Phage Host-Range Studies

- Productive infection host-range positives (culture clearing starting with a lower phage-to-bacterium ratio),

- Culture clearing but without evidence from optical density data of productive infection (i.e., starting with a phage-to-bacterium ratio of greater than 1),

- False productive-host-range negatives stemming from too low starting phage-to-bacterium ratios (Section 2.2), and

- True host-range negatives as evidenced by a consistent lack of culture-wide bacterial lysis, particularly as based on experiments initiated with a variety of phage multiplicities.

- Overall, this means that there could be differences in the perception of a phage’s optical density-based host range—as stemming from whether or not culture-wide bacterial lysis occurs—that are dependent on the magnitude of the starting ratio of phages to bacteria, i.e., with MOIinput.

- Productive infection host-range false positives due to the replication of phage host-range mutants and

- Productive infection host-range “false” false (and thus, ‘pseudofalse’) positives due to slow culture lysis by wild-type phages (host-range positives mimicking host-range negatives).

- The latter refers to a result that mimics a false positive. This is as appears to be due to the actions of a phage host-range mutant, but is actually a true host-range positive—it is just a wild-type phage that displays poor growth characteristics on a given test bacterium (Section 7.2.3).

7.2. Beware Phage Host-Range Mutants—False-Positive Outcomes

7.2.1. Distinguishing True from False Positives Using Timings

| Starting MOI 1 | Timing | Explanation | HR 2 Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | No lysis and no deviation 3 | Lack of productive infection or insufficient phage antibacterial virulence | Either host range negative (no phage productivity; Section 2.2) or false negative (low phage virulence; Section 7.2.3) |

| Low | No lysis but still relatively early deviation 3 | Productive infection but with slow or no lysis especially at higher bacterial densities | True host-range positive (but see Section 2.2); could be lysis inhibition (could be designated as intermediate bacterial sensitivity; Section 7.2.4) |

| Low to moderate | Tens of minutes to a few hours until lysis | Productive infection | True host-range positive; see, however, “Moderate to high” MOI, below |

| Moderate | Few to many hours until lysis but relatively early deviation 3 | Lysis inhibition 4 | True host-range positive 5 but could be mistaken for intermediate bacterial sensitivity (Section 7.2.4) |

| Moderate to high | Few to many hours until lysis but without relatively early deviation 3 | Host-range mutants | Host-range false positive (Section 7.2.2) |

| High | Normal latent period | Bacteriolytic infection | True host-range positive 6 |

| High | Few to many hours until lysis but with early deviation 3 | Lysis inhibition 4 | True host-range positive 6 but could be mistaken for intermediate bacterial sensitivity (Section 7.2.4) |

| Very high | Very early lysis | Lysis from without | Ambiguous; possible host-range false positive but probably host-range true positive (Section 6) |

7.2.2. Delays Associated with Phage Host-Range Mutants

7.2.3. Other Causes of Delayed or Altered Lysis Timing

- Reductions in wild-type starting phage titers will result in delays in culture-wide bacterial lysis (Section 5), or in failures of cultures to lyse at all (Section 2.2).

- Lysis inhibition will of course result in delays in overall lysis (Section 4), but not necessarily also delays in deviation (Figure 2; Section 7.2.4).

- Collectively, these different types of delays could be misinterpreted as false positives—as due to the action of phage host-range mutants—when they actually are true positives, just with delayed lysis kinetics (i.e., pseudofalse positives/lower-virulence phages on the specific bacterial host). This ambiguity again points to the utility of using alternative means to test host-range results if those results are not obviously positive nor obviously negative.

7.2.4. Bacterial Sensitivity

7.2.5. Recommendations

- Using kinetic rather than endpoint assays;

- Not starting with excessive phage multiplicities, in part because this introduces potential host-range mutant phages in higher numbers (below), but also because if wild-type phages are sufficiently high in starting titer, then lysis but without virion production could give a false-positive result (Section 6);

- Not starting with excessive bacterial concentrations so that cultures do not enter stationary phase before phage population growth has caught up with bacterial growth;

- Looking for relatively early deviation of phage-containing curves from those of bacteria, especially when starting with lower phage numbers, rather than explicitly requiring relatively early culture-wide bacterial lysis;

- Truncating experiments such that any impacts of delayed phage population growth never manifest, though this would also constitute a more stringent definition of phage host range, which should be recognized as such (i.e., see Section 7.2.3); and

- Testing ambiguous results by alternative means.

7.3. Host-Range Mutants Not Just an Issue with Optical Density-Based Methods

7.4. Testing for Host-Range Mutants

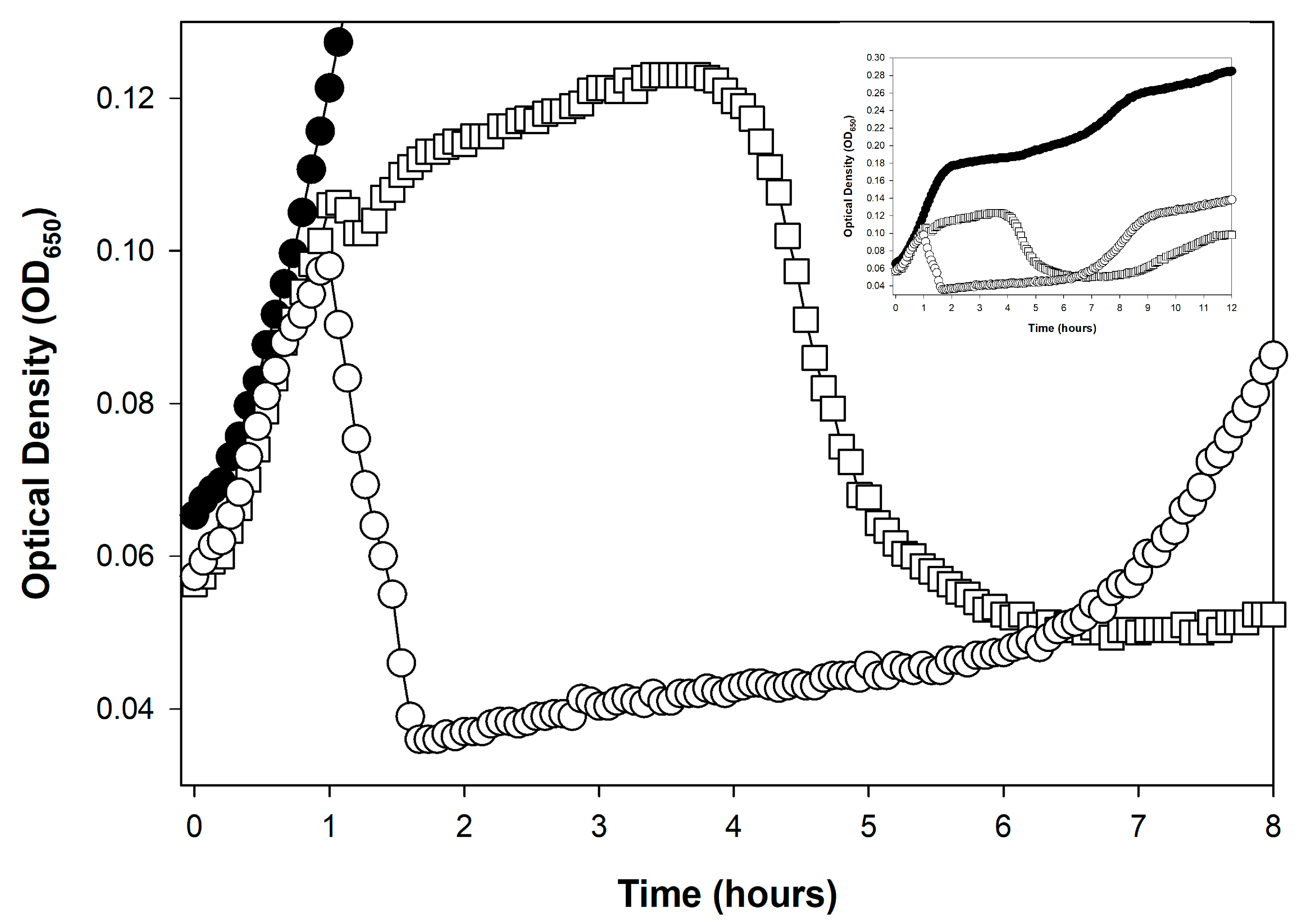

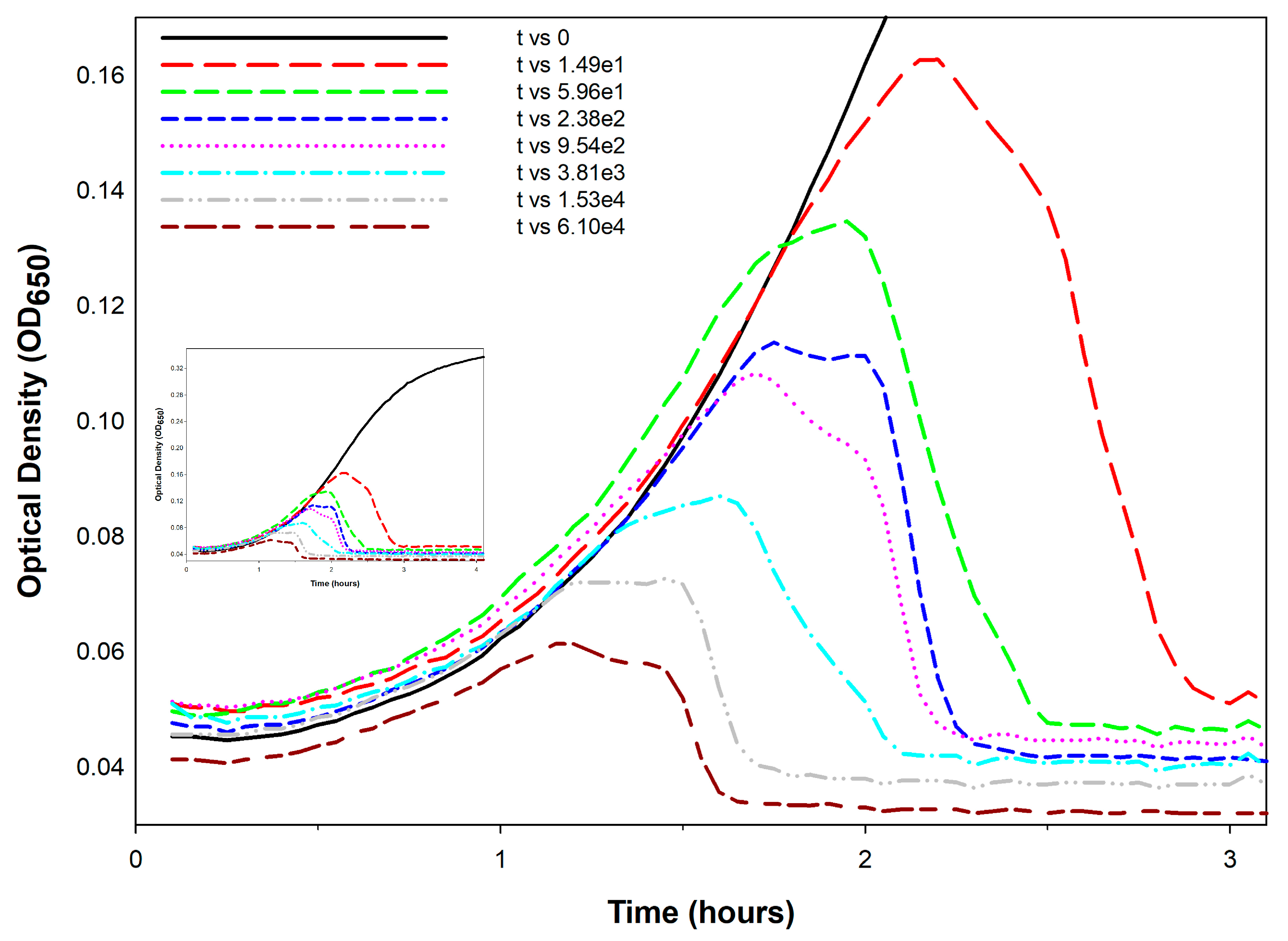

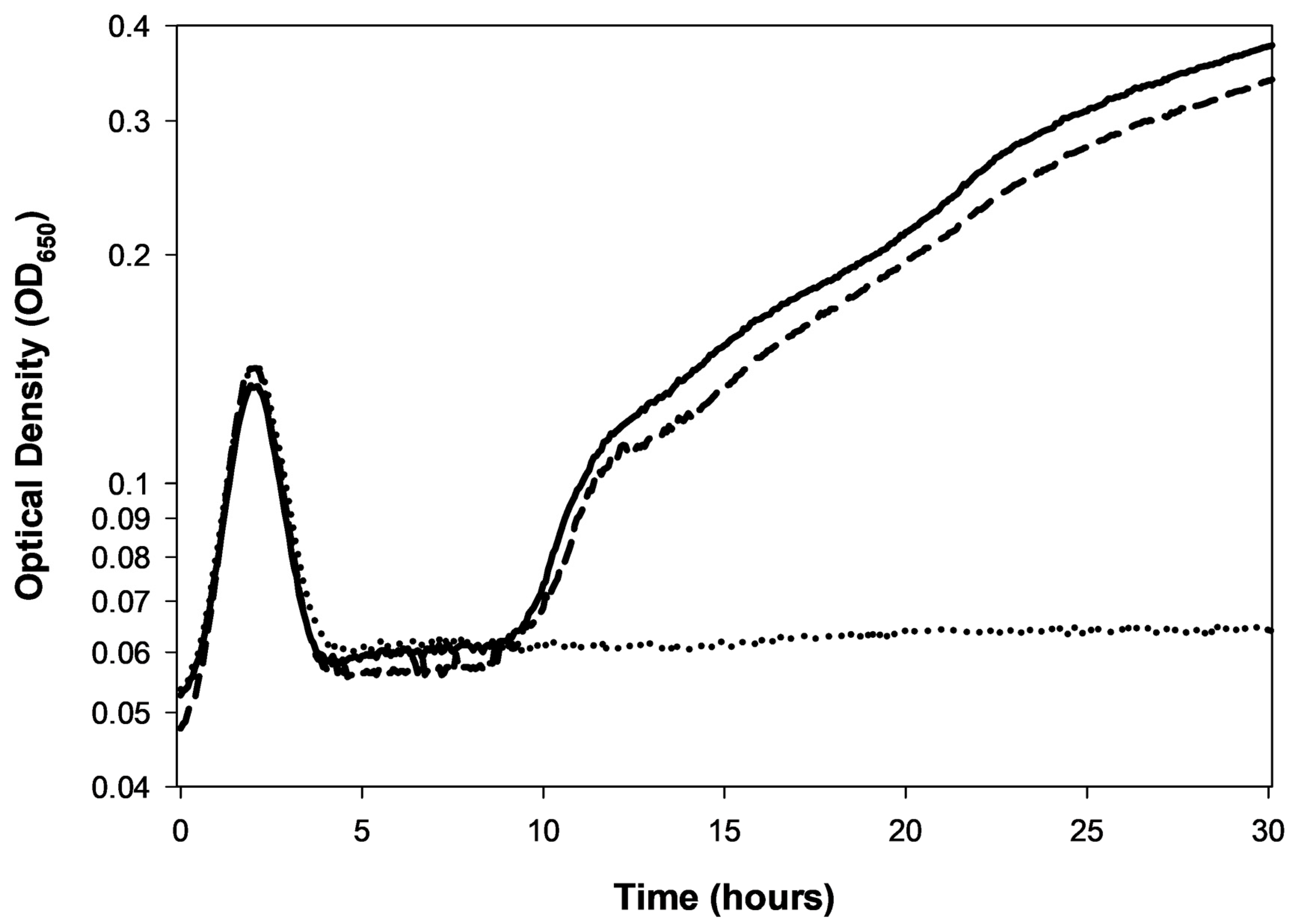

8. Bacterial Evolution of Phage Resistance

8.1. Kinetics of Bacterial Grow Back

8.2. Likelihood of Bacterial Mutation to Phage Resistance

8.3. Host Range vs. Resistance Suppression

8.3.1. The PHIDA Tool (“Phage-Host Interaction Data Analyzer”)

- “A”, culture-wide bacterial lysis and no culture regrowth (effectively infinite delay).

- “B”, culture-wide bacterial lysis followed by culture regrowth (delay is quantified).

- “C”, no or incomplete culture-wide bacterial lysis (ODmax is determined).

8.3.2. A Resistance-Suppression Index

8.3.3. Bacterial Hold Time

8.4. Problems of False Negatives and Mechanistic Uncertainty

- Cultures never reach sufficient bacterial numbers such that mutation to phage resistance is likely (e.g., Figure 6).

- Insufficiently long incubation times such that more slowly growing bacterial resistance mutants fail to be detected (e.g., Figure 2).

- Potential for antagonistic coevolution (Section 7.2), where within a single culture bacterial evolution of phage resistance could be countered by subsequent phage host-range evolution.

- The potential for bacterial evolution of resistance to phages is certainly relevant. Optical density-based approaches to assessing this potential likely can provide greater throughput than plating-based analyses [121,158]. At the same time, however, results of these assays may have more complex underpinnings than may be fully appreciated, particularly regarding underlying reasons for differences in culture regrowth delays.

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Lysis Profile Methods

References

- Duckworth, D.H. Who discovered bacteriophage? Bacteriol. Rev. 1976, 40, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Herelle, F. The Bacteriophage: Its Role in Immunity; Williams and Wilkins Co.: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, J. Bacteriophages; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1975; pp. 77–133. [Google Scholar]

- Dennehy, J.J.; Abedon, S.T. Adsorption: Phage acquisition of bacteria. In Bacteriophages: Biology, Technology, Therapy; Harper, D., Abedon, S.T., Burrowes, B.H., McConville, M., Eds.; Springer Nature AG: Cham, Switzerland; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Dennehy, J.J.; Abedon, S.T. Phage infection and lysis. In Bacteriophages: Biology, Technology, Therapy; Harper, D., Abedon, S.T., Burrowes, B.H., McConville, M., Eds.; Springer Nature AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 341–383. [Google Scholar]

- Mäntynen, S.; Laanto, E.; Oksanen, H.M.; Poranen, M.M.; Díaz-Muñoz, S.L. Black box of phage-bacterium interactions: Exploring alternative phage infection strategies. Open Biol. 2021, 11, 210188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakonjac, J.; Bennett, N.J.; Spagnuolo, J.; Gagic, D.; Russel, M. Filamentous bacteriophage: Biology, phage display and nanotechnology applications. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2011, 13, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupovic, M. ICTV Report Consortium ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Plasmaviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2018, 99, 617–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquero, D.P.; Liu, J.; Prangishvili, D. Egress of archaeal viruses. Cell Microbiol. 2021, 23, e13394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R. Phage lysis: Three steps, three choices, one outcome. J. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahill, J.; Young, R. Phage lysis: Multiple genes for multiple barriers. Adv. Virus Res. 2019, 103, 33–70. [Google Scholar]

- Górski, A.; Miedzybrodzki, R.; Borysowski, J. Phage Therapy: A Practical Approach; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Glonti, T.; Pirnay, J.-P. In vitro techniques and measurements of phage characteristics that are important for phage therapy success. Viruses 2022, 14, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marongiu, L.; Burkard, M.; Lauer, U.M.; Hoelzle, L.E.; Venturelli, S. Reassessment of historical clinical trials supports the effectiveness of phage therapy. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2022, 35, e0006222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, G.A.; Lodise, T.P.; Tamma, P.D.; Knisely, J.M.; Alexander, J.; Aslam, S.; Barton, K.D.; Bizzell, E.; Totten, K.M.C.; Campbell, J.; et al. Considerations for the use of phage therapy in clinical practice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0207121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic Fabijan, A.; Iredell, J.; Danis-Wlodarczyk, K.; Kebriaei, R.; Abedon, S.T. Translating phage therapy into the clinic: Recent accomplishments but continuing challenges. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strathdee, S.A.; Hatfull, G.F.; Mutalik, V.K.; Schooley, R.T. Phage therapy: From biological mechanisms to future directions. Cell 2023, 186, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Suh, G.A.; Cullen, G.D.; Perez, R.S.; Dharmaraj, T.; Chang, T.H.W.; Li, Z.; Chen, Q.; Green, S.I.; Lavigne, R.; et al. Bacteriophage therapy for multidrug-resistant infections: Current technologies and therapeutic approaches. J. Clin. Invest. 2025, 135, e187996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, A.P. A method for the quantitative determination of bacteriophage. J. Gen. Physiol. 1930, 13, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underwood, N.; Doermann, A.H. A photoelectric nephelometer. Rev. Scient. Instr. 1947, 18, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedon, S.T. Early use of kinetic 96-well plate readers to study phage-induced bacterial lysis: Who was first? Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storms, Z.J.; Teel, M.R.; Mercurio, K.; Sauvageau, D. The virulence index: A metric for quantitative analysis of phage virulence. PHAGE 2020, 1, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, B.G.; Campbell, J.H. A relationship between tolerance to colicin K and the mechanism of phage induced host cell lysis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1974, 133, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, B.G.; Campbell, J.H. Genetic and physiological control of host cell lysis by bacteriophage lambda. J. Virol. 1977, 23, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.H.; McClain, W.H. Roles of T4 gene 5 and gene s products in cell lysis. J. Virol. 1980, 34, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R. Bacteriophage lysis: Mechanisms and regulation. Microbiol. Rev. 1992, 56, 430–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, M.; Biswas, B.; Vincent, L.; Mokashi, V.; Schuch, R.; Bishop-Lilly, K.A.; Sozhamannan, S. Development of a high throughput assay for indirectly measuring phage growth using the OmniLog(TM) system. Bacteriophage 2012, 2, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.L.; Delbrück, M. The growth of bacteriophage. J. Gen. Physiol. 1939, 22, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.H. Bacteriophages; InterScience: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Stent, G.S. Molecular Biology of Bacterial Viruses; WH Freeman and Co.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, P.; Abedon, S.T. Practical methods for determining phage growth parameters. Meth. Mol. Biol. 2009, 501, 175–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kropinski, A.M. Practical advice on the one-step growth curve. Meth. Mol. Biol. 2018, 1681, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Abedon, S.T. Dos and don’ts of bacteriophage one-step growth. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubie, V.; Chalhoub, H.; Blasdel, B.; Dahma, H.; Merabishvili, M.; Glonti, T.; De Vos, N.; Quintens, J.; Pirnay, J.-P.; Hallin, M.; et al. Determination of phage susceptibility as a clinical diagnostic tool: A routine perspective. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1000721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panteleev, V.; Kulbachinskiy, A.; Gelfenbein, D. Evaluating phage lytic activity: From plaque assays to single-cell technologies. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1659093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, K.; Miller, E.S. Enumerating phage: The plaque assay. In Molecular Biology of Bacteriophage T4; Karam, J.D., Ed.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 427–429. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, K. Working with bacteriophages: Common techniques and methodological approaches. In Bacteriophages: Biology and Application; Kutter, E., Sulakvelidze, A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 437–494. [Google Scholar]

- Kropinski, A.M.; Mazzocco, A.; Waddell, T.E.; Lingohr, E.; Johnson, R.P. Enumeration of bacteriophages by double agar overlay plaque assay. Meth. Mol. Biol. 2009, 501, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocco, A.; Waddell, T.E.; Lingohr, E.; Johnson, R.P. Enumeration of bacteriophages by the direct plating plaque assay. Meth. Mol. Biol. 2009, 501, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocco, A.; Waddell, T.E.; Lingohr, E.; Johnson, R.P. Enumeration of bacteriophages using the small drop plaque assay system. Meth. Mol. Biol. 2009, 501, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Abedon, S.T.; Katsaounis, T.I. Detection of bacteriophages: Statistical aspects of plaque assay. In Bacteriophages: Biology, Technology, Therapy; Harper, D., Abedon, S.T., Burrowes, B.H., McConville, M., Eds.; Springer Nature AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 539–560. [Google Scholar]

- Serwer, P.; Hayes, S.J.; Thomas, J.A.; Demeler, B.; Hardies, S.C. Isolation of novel large and aggregating bacteriophages. Meth. Mol. Biol. 2009, 501, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R.E.O.; Rippon, J.E. Bacteriophage typing of Staphylococcus aureus. Epidemiol. Infect. 1952, 50, 320–353. [Google Scholar]

- Benzer, S.; Hudson, W.; Weidel, W.; Delbrück, M.; Stent, G.S.; Weigle, J.J.; Dulbecco, R.; Watson, J.D.; Wollman, E.L. A syllabus on procedures, facts, and interpretations in phage. In Viruses 1950; Delbrück, M., Ed.; California Institute of Technology: Pasadena, CA, USA, 1950; pp. 100–147. [Google Scholar]

- Dulbecco, R. Mutual exclusion between related phages. J. Bacteriol. 1952, 63, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagik, B.P. A Specific Reversible Inhibition of BacteriophageT2 of Escherichia coli by Host Cell Fragments. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, P.-Y. Properties of tryptophan-inactivated bacteriophage T4,38. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1956, 22, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T. Further considerations on how to improve phage therapy experimentation, practice, and reporting: Pharmacodynamics perspectives. Phage 2022, 3, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedon, S.T. Bacteriophage titering by optical density means: KOTE assays. Open Life Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, H. On the titration of bacteriophage and the particulate hypothesis. J. Gen. Physiol. 1927, 11, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feemster, R.F.; Wells, W.F. Experimental and statistical evidence of the particulate nature of the bacteriophage. J. Exp. Med. 1933, 58, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y.; Nguyen, T.V.P.; Homaee, E.; Golding, I. Using bacterial population dynamics to count phages and their lysogens. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.W.; Huggins, M.B. Effectiveness of phages in treating experimental Escherichia coli diarrhoea in calves, piglets and lambs. J. General. Microbiol. 1983, 129, 2659–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Y.D.; Johnson, R.P.; Xu, Y.; McAllister, T.A.; Sharma, R.; Louie, M.; Stanford, K. Host range and lytic capability of four bacteriophages against bovine and clinical human isolates of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 107, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wahab, L.; Gill, J.J. Development and validation of a microtiter plate-based assay for determination of bacteriophage host range and virulence. Viruses 2018, 10, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopacki, M.; Grygorcewicz, B.; Dołęgowska, B.; Kordas, M.; Rakoczy, R. PhageScore: A simple method for comparative evaluation of bacteriophages lytic activity. Biochem. Eng. J. 2020, 161, 107652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, M.E.K.; Hodges, F.E.; Nale, J.Y.; Mahony, J.; van Sinderen, D.; Kaczorowska, J.; Alrashid, B.; Akter, M.; Brown, N.; Sauvageau, D.; et al. Analysis of selection methods to develop novel phage therapy cocktails against antimicrobial resistant clinical isolates of bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 613529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.H. The calcium requirement of coliphage T5. J. Immunol. 1949, 62, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, B.S.; Krueger, A.P. The B mycoides N host-virus system. II. Interrelation of phage growth, bacterial multiplication, and lysis in infections of the indicator strain of B. mycoides N with phage N in nutrient broth. J. Gen. Physiol. 1952, 36, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelmans, R. Le dosage du bactériophage. Compt. Rend. Soc. Biol. 1921, 85, 1098. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y.D.; Stanford, K.; Kropinski, A.M.; Ackermann, H.-W.; Johnson, R.P.; She, Y.M.; Ahmed, R.; Villegas, A.; McAllister, T.A. Genomic, proteomic and physiological characterization of a T5-like bacteriophage for control of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Y.D.; McAllister, T.A.; Nash, J.H.; Kropinski, A.M.; Stanford, K. Four Escherichia coli O157:H7 phages: A new bacteriophage genus and taxonomic classification of T1-like phages. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanishvili, N. A Literature Review of the Practical Application of Bacteriophage Research; Nova Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Burrowes, B.H.; Molineux, I.J.; Fralick, J.A. Directed in vitro evolution of therapeutic bacteriophages: The Appelmans protocol. Viruses 2019, 11, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, J.J.; Wichman, H.A.; Krone, S.M.; Molineux, I.J. Controlling recombination to evolve bacteriophages. Cells 2024, 13, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, N.; Hammerl, J.A.; Swierczewski, B.E.; Wurstle, S.; Bugert, J.J. Appelmans Protocol for in vitro Klebsiella pneumoniae phage host range expansion leads to induction of the novel temperate linear plasmid prophage vB_KpnS-KpLi5. Virus Genes. 2025, 61, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.N.; Clark, J.R.; Jang, E.; D’Souza, R.; Nguyen, L.P.; Pinto, N.A.; Yoo, S.; Abadie, R.; Maresso, A.W.; Yong, D. Appelmans protocol—A directed in vitro evolution enables induction and recombination of prophages with expanded host range. Virus Res. 2024, 339, 199272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, J.D.; Moineau, S. Homologous recombination between a lactococcal bacteriophage and the chromosome of its host strain. Virology 2000, 270, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelmans, R. Le Dosage Du Bactériophage, Note de R. Appelmans, Présentée par R. Bruynoghe, Réunion de la Société Belge de Biologie, 1921, pp. 1098–1099, A Google Translation. A Smaller Flea. 2024. Available online: https://asmallerflea.org/2024/12/23/le-dosage-du-bacteriophage-note-de-r-appelmans-presentee-par-r-bruynoghe-reunion-de-la-societe-belge-de-biologie-1921-pp-1098-1099-a-google-translation/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Appelmans, R. Le bacteriophage dans l’organisme. Comp. Rend. Soc. Biol. 1921, 85, 722–724. [Google Scholar]

- Bruynoghe, R.; Appelmans, R. La neutralisation des bactériophages de provenance différente. Comp. Rend. Soc. Biol. 1922, 86, 96–98. [Google Scholar]

- Appelmans, R.; Wagemans, J. Bactériophages de diverses provenances. Comp. Rend. Soc. Biol. 1922, 86, 738–739. [Google Scholar]

- Appelmans, R. Le Bacteriophage Dans l’organisme. Note by R. Appelmans, Presented by R. Bruynoghe. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences, 1921, 85:722–724, A Claude.ai Translation. A Smaller Flea. 2025. Available online: https://asmallerflea.org/2025/10/17/le-bacteriophage-dans-lorganisme-note-by-r-appelmans-presented-by-r-bruynoghe-comptes-rendus-de-lacademie-des-sciences-1921-85722-724-a-claude-ai-translation/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Maillard, J.Y.; Beggs, T.S.; Day, M.J.; Hudson, R.A.; Russell, A.D. The use of an automated assay to assess phage survival after a biocidal treatment. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1996, 80, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, P.E.; Draghi, J.A.; Wilpiszeski, R. High-throughput analysis of growth differences among phage strains. J. Microbiol. Meth. 2012, 88, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajnovic, D.; Munoz-Berbel, X.; Mas, J. Fast phage detection and quantification: An optical density-based approach. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazanin, M.; Vasen, E.; Vilaro, J.C.; An, W.; Turner, P.E. Quantifying phage infectivity from characteristics of bacterial population dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2513377122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T. Evolution of bacteriophage latent period length. In Evolutionary Biology: New Perspectives on its Development; Dickins, T.E., Dickens, B.J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 375–426. [Google Scholar]

- Delbrück, M. The growth of bacteriophage and lysis of the host. J. Gen. Physiol. 1940, 23, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, J.E. Evolution of the genetic switch in temperate bacteriophage. I. Basic theory. J. Theor. Biol. 1996, 179, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, J.W. Lysogeny, prophage induction, and lysogenic conversion. In Phages: Their Role in Bacterial Pathogenesis and Biotechnology; Waldor, M.K., Friedman, D.I., Adhya, S.L., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- York, M.K.; Stodolsky, M. Characterization of P1 argF derivatives from Escherichia coli K12 transduction. II. Role of P1 in specialized transduction of argF. Virology 1982, 120, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, J.M.; Fusselman, R.; Hise, J.; Chiou, L.; Smith-Grillo, D.; Schultz, J.; Young, R. Cell lysis by induction of cloned lambda lysis genes. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1981, 182, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delbrück, M. Bacterial viruses or bacteriophages. Biol. Rev. 1946, 21, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danis-Wlodarczyk, K.M.; Cai, A.; Chen, A.; Gittrich, M.R.; Sullivan, M.B.; Wozniak, D.J.; Abedon, S.T. Friends or foes? Rapid determination of dissimilar colistin and ciprofloxacin antagonism of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phages. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T. Lysis and the interaction between free phages and infected cells. In The Molecular Biology of Bacteriophage T4; Karam, J.D., Kutter, E., Carlson, K., Guttman, B., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 397–405. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.J.; Henning, U. Superinfection exclusion by T-even-type coliphages. Trends Microbiol. 1994, 2, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucher, M.J.; Czyz, D.M. Phage against the machine: The SIE-ence of superinfection exclusion. Viruses 2024, 16, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasman, L.M.; Kasman, A.; Westwater, C.; Dolan, J.; Schmidt, M.G.; Norris, J.S. Overcoming the phage replication threshold: A mathematical model with implications for phage therapy. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 5557–5564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T. Phage therapy dosing: The problem(s) with multiplicity of infection (MOI). Bacteriophage 2016, 6, e1220348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, A.D. Mutation of bacteriophage with respect to type of plaque. Genetics 1946, 31, 620–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, A.D. Spontaneous mutations in bacterial viruses. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1946, 11, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Doermann, A.H. Lysis and lysis inhibition with Escherichia coli bacteriophage. J. Bacteriol. 1948, 55, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schito, G.C. Dvelopment of coliphage N4: Ultrastructural studies. J. Virol. 1974, 13, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T. Look who’s talking: T-even phage lysis inhibition, the granddaddy of virus-virus intercellular communication research. Viruses 2019, 11, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hays, S.G.; Seed, K.D. Dominant Vibrio cholerae phage exhibits lysis inhibition sensitive to disruption by a defensive phage satellite. eLife 2020, 9, e53200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedon, S.T. Bacteriophage T4 resistance to lysis-inhibition collapse. Genet. Res. 1999, 74, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.A.; Struck, D.K.; Young, R. The T4 RI antiholin has an N-terminal signal anchor release domain that targets it for degradation by DegP. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 7618–7625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, S.H.; Kuznetsov, V.; Tran, T.A.; Sacchettini, J.C.; Young, R. Protein determinants of phage T4 lysis inhibition. Protein Sci. 2012, 21, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Young, R. The last r locus unveiled: T4 RIII is a cytoplasmic antiholin. J. Bacteriol. 2016, 198, 2448–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehner-Breitfeld, D.; Schwarzkopf, J.M.F.; Young, R.; Kondabagil, K.; Bruser, T. The phage T4 antiholin RI has a cleavable signal peptide, not a SAR domain. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 712460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juskauskas, A.; Zajanckauskaite, A.; Meskys, R.; Ger, M.; Kaupinis, A.; Valius, M.; Truncaite, L. Interaction between phage T4 protein RIII and host ribosomal protein S1 inhibits endoribonuclease RegB activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan-Alolama, M.I.; Amin, A.; Vijayan, R.; El-Tarabily, K.A. Isolation, Characterization, and Comparative Genomic Analysis of Bacteriophage Ec_MI-02 from Pigeon Feces Infecting Escherichia coli O157:H7. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvid, U.; Mitarai, N. Competitive advantages of T-even phage lysis inhibition in response to secondary infection. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2024, 20, e1012242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Ryu, S. Elucidation of molecular function of phage protein responsible for optimization of host cell lysis. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzkopf, J.M.F.; Mehner-Breitfeld, D.; Bruser, T. A dimeric holin/antiholin complex controls lysis by phage T4. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1419106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Ryu, S. Genetic insights into novel lysis suppression by phage CSP1 in Escherichia coli. J. Microbiol. 2025, 63, e2501013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, I.-N.; Dykhuizen, D.E.; Slobodkin, L.B. The evolution of phage lysis timing. Evol. Ecol. 1996, 10, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, M.L.; Krisch, R.E. Enlargement of Escherichia coli after bacteriophage infection I. description of phenomenon. J. Virol. 1971, 8, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, M.L.; Krisch, R.E. Enlargement of Escherichia coli after bacteriophage infection II. proposed mechanism. J. Virol. 1971, 8, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asami, K.; Xing, X.H.; Tanji, Y.; Unno, H. Synchronized disruption of Escherichia coli cells by T4 phage infection. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1997, 83, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicalho, R.C.; Santos, T.M.; Gilbert, R.O.; Caixeta, L.S.; Teixeira, L.M.; Bicalho, M.L.; Machado, V.S. Susceptibility of Escherichia coli isolated from uteri of postpartum dairy cows to antibiotic and environmental bacteriophages. Part I: Isolation and lytic activity estimation of bacteriophages. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Stencel, J.M.; Hicks, C.D.; Payne, F.; Ozevin, D. Acoustic emission signal of Lactococcus lactis before and after Inhibition with NaN 3 and infection with bacteriophage c2. Int. Sch. Res. Not. Microbiol. 2013, 2013, 257313. [Google Scholar]

- Davidi, D.; Sade, D.; Schuchalter, S.; Gazit, E. High-throughput assay for temporal kinetic analysis of lytic coliphage activity. Anal. Biochem. 2014, 444, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patpatia, S.; Schaedig, E.; Dirks, A.; Paasonen, L.; Skurnik, M.; Kiljunen, S. Rapid hydrogel-based phage susceptibility test for pathogenic bacteria. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1032052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soro, O.; Kigen, C.; Nyerere, A.; Gachoya, M.; Georges, M.; Odoyo, E.; Musila, L. Characterization and anti-biofilm activity of lytic Enterococcus phage vB_Efs8_KEN04 against clinical isolates of multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecalis in Kenya. Viruses 2024, 16, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, K.G.; Cook, B.W.M.; Lightly, T.J.; Court, D.A.; Theriault, S.S. Investigation into scalable and efficient enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli bacteriophage production. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, I.; Kuznetsov, V.; Chang, J.-Y.; Zhang, J.; Moussa, H.; Young, R.; Sacchettini, J.C. The structural basis of T4 phage lysis control: DNA as the signal for lysis inhibition. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 4623–4636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, W. Lysis inhibition in Escherichia coli infected with bacteriophage T4. J. Virol. 1967, 1, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedon, S.T. Lysis of lysis inhibited bacteriophage T4-infected cells. J. Bacteriol. 1992, 174, 8073–8080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerec, M.; Fano, U. Bacteriophage-resistant mutants in Escherichia coli. Genetics 1945, 30, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luria, S.E. Reactivation of irradiated bacteriophage by transfer of self-reproducing units. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1947, 33, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T. The murky origin of Snow White and her T-even dwarfs. Genetics 2000, 155, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanni, Y.T. Lysis inhibition with a mutant of bacteriophage T5. Virology 1958, 5, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenstark, A. Bacteriophage techniques. Meth. Virol. 1967, 1, 449–524. [Google Scholar]

- Abedon, S.T.; Danis-Wlodarczyk, K.M.; Wozniak, D.J.; Sullivan, M.B. Improving phage-biofilm in vitro experimentation. Viruses 2021, 13, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddison, P.; Abedon, S.T.; Dressman, H.K.; Gailbreath, K.; Tracy, J.; Mosser, E.; Neitzel, J.; Guttman, B.; Kutter, E. The roles of the bacteriophage T4 r genes in lysis inhibition and fine-structure genetics: A new perspective. Genetics 1998, 148, 1539–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, R.H.; Bolle, A.; Steinberg, C.M.; Kellenberger, E.; Boy de la Tour, E.; Chevalley, R.; Edgar, R.S.; Susman, M.; Denhardt, G.H.; Lielausis, A. Physiological studies of conditional lethal mutants of bacteriophage T4D. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1963, 28, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagida, M.; Ahmad-Zadeh, C. Determination of gene product positions in bacteriophage T4 by specific antibody association. J. Mol. Biol. 1970, 51, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, E. Recognition, attachment, and injection. In Bacteriophage T4; Mathews, C.K., Kutter, E.M., Mosig, G., Berget, P.B., Eds.; American Society for Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 1983; pp. 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Freyberger, H.R.; He, Y.; Roth, A.L.; Nikolich, M.P.; Filippov, A.A. Effects of Staphylococcus aureus bacteriophage K on expression of cytokines and activation markers by human dendritic cells in vitro. Viruses 2018, 10, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paranos, P.; Pournaras, S.; Meletiadis, J. A single-layer spot assay for easy, fast, and high-throughput quantitation of phages against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2024, 62, e0074324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirnay, J.-P. Phage therapy in the year 2035. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T. Lysis from without. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channabasappa, S.; Durgaiah, M.; Chikkamadaiah, R.; Kumar, S.; Joshi, A.; Sriram, B. Efficacy of novel antistaphylococcal ectolysin P128 in a rat model of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01358-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrich, J. Lysis of T4-infected bacteria in the absence of lysozyme. Virology 1968, 35, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molineux, I.J. Fifty-three years since Hershey and Chase; much ado about pressure but which pressure is it? Virology 2006, 344, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconti, N. Resistance to lysis from without in bacteria infected with T2 bacteriophage. J. Bacteriol. 1953, 66, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutter, E. Phage host range and efficiency of plating. Meth. Mol. Biol. 2009, 501, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Khan Mirzaei, M.; Nilsson, A.S. Isolation of phages for phage therapy: A comparison of spot tests and efficiency of plating analyses for determination of host range and efficacy. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradeepa, P.; Prasad, M.P.; Aswini, V.; Rexon, M. Anti-microbial activity of probiotic Lactobacilli and optimization of bacteriocin production. Int. J. Sci. Res. Dev. 2013, 1, 1354–1356. [Google Scholar]

- Skusa, R.; Gross, J.; Kohlen, J.; Schafmayer, C.; Ekat, K.; Podbielski, A.; Warnke, P. Proof-of-concept standardized approach using a single-disk method analogous to antibiotic disk diffusion assays for routine phage susceptibility testing in diagnostic laboratories. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e0030922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmelcher, M.; Donovan, D.M.; Loessner, M.J. Bacteriophage endolysins as novel antimicrobials. Future Microbiol. 2012, 7, 1147–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, B.; Kong, M.; Lee, Y.; Ryu, S. Development of a novel chimeric endolysin, Lys109 with enhanced lytic activity against Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 615887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Bao, X.; Hong, W.; Wang, A.; Wang, K.; Dong, H.; Hou, J.; Govinden, R.; Deng, B.; Chenia, H.Y. Biological characterization and evolution of bacteriophage T7-Δholin during the serial passage process. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 705310. [Google Scholar]

- Nakonieczna, A.; Topolska-Wos, A.; Lobocka, M. New bacteriophage-derived lysins, LysJ and LysF, with the potential to control Bacillus anthracis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, K.; Miller, E.S. Working with T4. In Molecular Biology of Bacteriophage T4; Karam, J.D., Carlson, K., Miller, E.S., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 421–426. [Google Scholar]

- Abedon, S.T.; Hyman, P.; Thomas, C. Experimental examination of bacteriophage latent-period evolution as a response to bacterial availability. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 7499–7506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doermann, A.H. The intracellular growth of bacteriophages I. liberation of intracellular bacteriophage T4 by premature lysis with another phage or with cyanide. J. Gen. Physiol. 1952, 35, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.F.; Doermann, A.H. The intracellular growth of bacteriophages. II. The growth of T3 studied by sonic disintegration and by T6-cyanide lysis of infected cell. J. Gen. Physiol. 1952, 35, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doermann, A.H. The eclipse in the bacteriophage life cycle. In Phage and the Origins of Molecular Biology; Cairns, J., Stent, G.S., Watson, J.D., Eds.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 1966; pp. 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, P. The genetics of the Luria-Latarjet effect in bacteriophage T4: Evidence for the involvement of multiple DNA repair pathways. Genet. Res. 1993, 62, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, F.W. The amber mutants of phage T4. Genetics 1995, 141, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyman, P.; Abedon, S.T. Bacteriophage host range and bacterial resistance. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 70, 217–248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ross, A.; Ward, S.; Hyman, P. More Is better: Selecting for broad host range bacteriophages. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, A. Probiotic biofilm modified scaffolds for facilitating osteomyelitis treatment through sustained release of bacteriophage and regulated macrophage polarization. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 30, 101444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Karaynir, A.; Salih, H.; Oncu, S.; Bozdogan, B. Characterization, genome analysis and antibiofilm efficacy of lytic Proteus phages RP6 and RP7 isolated from university hospital sewage. Virus Res. 2023, 326, 199049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luria, S.E.; Delbrück, M. Mutations of bacteria from virus sensitivity to virus resistance. Genetics 1943, 28, 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lythgoe, K.; Chao, L. Mechanisms of coexistence of a bacteria and a bacteriophage in a spatially homogeneous environment. Ecol. Lett. 2003, 6, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrani, S.; Wurtzel, O.; Sharon, I.; Sorek, R.; Lindell, D. Genomic island variability facilitates Prochlorococcus-virus coexistence. Nature 2011, 474, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.C.T.; Friman, V.P.; Smith, M.C.M.; Brockhurst, M.A. Cross-resistance is modular in bacteria-phage interactions. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2006057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallereau, A.; Meaden, S.; van Houte, S.; Westra, E.R.; Rollie, C. The effect of bacterial mutation rate on the evolution of CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 374, 20180094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burmeister, A.R.; Fortier, A.; Roush, C.; Lessing, A.J.; Bender, R.G.; Barahman, R.; Grant, R.; Chan, B.K.; Turner, P.E. Pleiotropy complicates a trade-off between phage resistance and antibiotic resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11207–11216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhurst, M.A.; Koskella, B.; Zhang, Q.G. Bacteria-phage antagonistic coevolution and the implications for phage therapy. In Bacteriophages: Biology, Technology, Therapy; Harper, D.R., Abedon, S.T., Burrowes, B.H., McConville, M., Eds.; Springer Nature AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 231–251. [Google Scholar]

- Abedon, S.T. A primer on phage-bacterium antagonistic coevolution. In Bacteriophages as Drivers of Evolution: An Evolutionary Ecological Perspective; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 293–315. [Google Scholar]

- Vandersteegen, K.; Kropinski, A.M.; Nash, J.H.; Noben, J.P.; Hermans, K.; Lavigne, R. Romulus and Remus, two phage isolates representing a distinct clade within the Twortlikevirus genus, display suitable properties for phage therapy applications. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 3237–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, J.W. Rates of spontaneous mutation among RNA viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 4171–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieper, F.; Wittmann, J.; Bunk, B.; Sproer, C.; Hafner, M.; Willy, C.; Musken, M.; Ziehr, H.; Korf, I.H.E.; Jahn, D. Systematic bacteriophage selection for the lysis of multiple Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1597009. [Google Scholar]

- Luria, S.E. Mutations of bacterial viruses affecting their host range. Genetics 1945, 30, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, W.D.; Klaenhammer, T.R. Characteristics of phage abortion conferred in lactococci by the conjugal plasmid pTR2030. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1990, 136, 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moineau, S.; Durmaz, E.; Pandian, S.; Klaenhammer, T.R. Differentiation of two abortive mechanisms by using monoclonal antibodies directed toward lactococcal bacteriophage capsid proteins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedon, S.T. Detection of bacteriophages: Phage plaques. In Bacteriophages: Biology, Technology, Therapy; Harper, D.R., Abedon, S.T., Burrowes, B.H., McConville, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland; New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 507–538. [Google Scholar]

- Welkos, S.; Schreiber, M.; Baer, H. Identification of Salmonella with the O-1 bacteriophage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1974, 28, 618–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.J.; Denyer, S.P.; Maillard, J.Y. Rapid and quantitative automated measurement of bacteriophage activity against cystic fibrosis isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 110, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ormala-Odegrip, A.M.; Mappes, J.; Laakso, J. Top-down effects of a lytic bacteriophage and protozoa on bacteria in aqueous and biofilm phases. Ecol. Evol. 2014, 4, 4444–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, A.; Gifford, D.R.; MacLean, R.C.; King, K.C. Parasite diversity drives rapid host dynamics and evolution of resistance in a bacteria-phage system. Evolution 2016, 70, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrella, L.A.; Quinones, J.; Henry, M.; Hannah, R.M.; Pope, R.K.; Hamilton, T.; Teneza-Mora, N.; Hall, E.; Biswajit, B. Characterization of novel Staphylococcus aureus lytic phage and defining their combinatorial virulence using the OmniLog® system. Bacteriophage 2016, 6, e1219440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azam, A.H.; Sato, K.; Miyanaga, K.; Nakamura, T.; Ojima, S.; Kondo, K.; Tamura, A.; Yamashita, W.; Tanji, Y.; Kiga, K. Selective bacteriophages reduce the emergence of resistant bacteria in bacteriophage-antibiotic combination therapy. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0042723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, N.; Chehreghani, M.; Moineau, S.; Charette, S.J. Centroid of the bacterial growth curves: A metric to assess phage efficiency. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Barceló, C.; Turner, P.E.; Buckling, A. Mitigation of evolved bacterial resistance to phage therapy. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2022, 53, 101201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oromi-Bosch, A.; Antani, J.D.; Turner, P.E. Developing phage therapy that overcomes the evolution of bacterial resistance. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2023, 10, 503–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedon, S.T. Phage therapy: Combating evolution of bacterial resistance to phages. Viruses 2025, 17, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiey, M.; Grace, E.R.; Pawlos, P.; Bihi, M.; Ahmed, H.; Hampson, G.E.; Al, R.A.; Alharbi, L.; Sanchez-Lucas, R.; Korotania, N.; et al. Coevolutionary analysis of Pseudomonas syringae-phage interactions to help with rational design of phage treatments. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Soto, C.E.; Cucic, S.; Lin, J.T.; Kirst, S.; Mahmoud, E.S.; Khursigara, C.M.; Anany, H. PHIDA: A high throughput turbidimetric data analytic tool to compare host range profiles of bacteriophages isolated using different enrichment methods. Viruses. 2021, 13, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Chen, Q.; Echterhof, A.; Pennetzdorfer, N.; McBride, R.C.; Banaei, N.; Burgener, E.B.; Milla, C.E.; Bollyky, P.L. A blueprint for broadly effective bacteriophage-antibiotic cocktails against bacterial infections. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shi, T.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. A novel method to create efficient phage cocktails via use of phage-resistant bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e02323-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, K.; Fackler, J.R.; Rivas, Z.; Mandrekar, J.; Greenwood-Quaintance, K.E.; Patel, R. A comparison of phage susceptibility testing with two liquid high-throughput methods. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1386245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, K.; Komarow, L.; Ellison, D.W.; Filippov, A.A.; Nikolich, M.P.; Fackler, J.R.; Lee, M.; Nair, A.; Agrawal, P.; Tamma, P.D.; et al. Interlaboratory comparison of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage susceptibility testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2023, 61, e0061423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyman, P. Phages for phage therapy: Isolation, characterization, and host range breadth. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirnay, J.P.; Djebara, S.; Steurs, G.; Griselain, J.; Cochez, C.; De, S.S.; Glonti, T.; Spiessens, A.; Vanden Berghe, E.; Green, S.; et al. Personalized bacteriophage therapy outcomes for 100 consecutive cases: A multicentre, multinational, retrospective observational study. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 1434–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phenomenon | Description |

|---|---|

| Wavelength of light | Function of energy of photons; denotes colors within the visible spectrum, e.g., 400 nm (violet; higher energy) to 700 nm (red; lower energy). |

| Light intensity | Number of photons received by a detector per unit time but varying as a function of wavelength. |

| Light intensity detectors | Instruments that detect light intensity at specific wavelengths such as colorimeters, spectrophotometers, nephelometers, and turbidimeters. |

| Turbidimetry | Determination of degrees of scattering of light as resulting in declines in light intensity. |

| Colorimetry | As used here, the determination of concentrations of substances based on their ability to reduce the intensity of light. |

| Optical density (OD) | Degree of interference with the passage of light as typically defined in terms of a specific wavelength; a medium has an optical density that, unless it is transparent, has a value that is greater than 0. |

| Endpoint assay | Single measurement following some previously specified duration of incubation. |

| Kinetic assay | Multiple measurements taken over time, such as of the optical density of a culture, as determined over the duration of an incubation. |

| Lysis | Destruction of a bacterial cell envelope such as due to the action of cell wall- and membrane-disrupting phage-encoded proteins. |

| Lysis profile | Graphical representation of the kinetic impact of a lytic infection on a bacterial culture over time in terms of that culture’s turbidity. |

| Lysis from within | Phage-induced bacterial lysis as mediated by intracellularly located phage proteins. This is the lysis normally observed with lysis profiles. |

| Lysis from without | Premature lysis seen with some phages resulting from rapid, high-multiplicity virion adsorption without virion production. |

| Lytic phage | Bacterial virus for which successful virion-productive infections end in lysis rather than being associated with continuous virion release. |

| Culture-wide bacterial lysis | Conversion of a turbid bacterial culture to or nearer to the optical density of uninoculated broth. |

| Lytic cycle | Productive phage infection that ends with virion release and which follows either virion adsorption or prophage induction. |

| Lysogenic cycle | Phage infection by a temperate phage that is not virion productive but in which the phage genome replicates as a prophage. |

| Induced lytic cycle | Phage lytic cycle associated with conversion of a lysogenic cycle to a virion-productive phage infection that ends in lysis. |

| Purely lytic cycle | Lytic cycle that begins with phage adsorption rather than with prophage induction; this contrasts with an “induced lytic cycle”. |

| Latent period | Duration of a lytic cycle, e.g., as determined by employing either lysis profile or one-step growth experiments. |

| Burst size | Number of virions released per phage-infected bacterium produced per lytic cycle. |

| One-step growth | Single round of a phage lytic cycle (typically purely lytic) that is assessed in terms of increases in plaque-forming units over time. |

| Multistep growth | Sequential occurrence of more than one especially purely lytic cycle as resulting in prolonged phage population growth. |

| Phage population growth | As used here, refers to multistep growth involving a series of virion adsorption steps that are followed by phage purely lytic cycles. |

| Secondary adsorption | Distinguishing the first phage to infect a bacterium from subsequently adsorbing (secondary) phages; may induce lysis inhibition. |

| Lysis inhibition | Extension of purely lytic cycle that occurs in certain phages in response to the secondary adsorption of an already phage-infected bacterium. |

| Multiplicity of infection | Used to describe ratios of phages—whether added, adsorbed, or infecting—to phage susceptible bacteria; abbreviated as MOI. |

| Multiplicity | Ratio of phages to bacteria, either at the point of phage addition (MOIinput) or following phage adsorption to bacteria (MOIactual). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abedon, S.T. Optical Density-Based Methods in Phage Biology: Titering, Lysis Timing, Host Range, and Phage-Resistance Evolution. Viruses 2025, 17, 1573. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121573

Abedon ST. Optical Density-Based Methods in Phage Biology: Titering, Lysis Timing, Host Range, and Phage-Resistance Evolution. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1573. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121573

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbedon, Stephen T. 2025. "Optical Density-Based Methods in Phage Biology: Titering, Lysis Timing, Host Range, and Phage-Resistance Evolution" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1573. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121573

APA StyleAbedon, S. T. (2025). Optical Density-Based Methods in Phage Biology: Titering, Lysis Timing, Host Range, and Phage-Resistance Evolution. Viruses, 17(12), 1573. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121573