1. Introduction

Forests constitute the core component of terrestrial ecosystems and occupy a pivotal position in the global ecological-security architecture. Beyond supplying essential forest products such as timber and medicinal resources, they function as the planet’s largest carbon sinks, fulfilling an irreplaceable ecological role in carbon dioxide absorption, climate change mitigation, biodiversity maintenance, and the regulation of soil and water resources [

1]. Consequently, the sustainable development of the forestry sector is crucial for achieving overall economic growth, environmental protection, and the “Dual Carbon” targets (carbon peaking and carbon neutrality). Against this backdrop, Green Total Factor Productivity (GTFP)—the core indicator for measuring the quality and sustainability of forestry-enterprise development—becomes especially critical [

2]. GTFP captures a forestry firm’s ability to maximize economic returns while simultaneously achieving resource conservation and environmental friendliness. Despite its importance, forestry enterprises currently face significant challenges in promoting GTFP, including information asymmetry, financing constraints, and elevated costs of environmental compliance [

3].

To address these challenges and promote GTFP, governments and academics have extensively explored its determinants. For instance, Wu et al. investigated the influence of financial support on forestry firms’ GTFP [

4]; Dong et al. confirmed that internet development significantly promotes GTFP and identified notable spatial spillover effects [

5]; and Yuan and Xiang analyzed the effects of environmental-regulation policies on green technological innovation and GTFP [

6]. These studies establish a crucial foundation for understanding GTFP in the forestry sector. However, they often overlook the potential impact of profound changes in government governance models on micro-level firm efficiency. To bridge this gap, this study aims to deeply investigate the effect of digital government on the GTFP of forestry enterprises.

With the widespread adoption of new-generation information technologies, governments have begun using digital technologies for governance—known as digital government transformation—thereby reshaping the relationship between the state and enterprises. By leveraging unified digital platforms that use big data and blockchain for the digital confirmation of forest tenure, digital government can effectively resolve the long-standing challenges of valuing forestry assets and quantifying collateral [

7,

8]. In such a setting, digital government can significantly decrease information asymmetry and transaction costs, thereby reducing financing constraints and promoting GTFP. In addition, digital government can substantially accelerate the digital transformation of forestry enterprises by providing a unified, efficient, and trustworthy digital infrastructure [

9,

10]. This, in turn, serves as a crucial driver of GTFP [

11,

12].

China provides a compelling context for examining this relationship. As the nation with the world’s largest planted-forest area and a forestry industry undergoing rapid modernization, China’s experience offers valuable insights for policy-making and theoretical exploration in both developed and developing economies. In this context, exploring the factors influencing GTFP is highly relevant because the findings can serve as a critical reference point for other countries seeking to promote their own GTFP and achieve sustainable development goals. Moreover, the phased implementation of China’s Information Benefiting the People (IBP) policy provides a crucial source of exogenous variation in the construction of digital government. This policy shock creates a unique quasi-experimental opportunity that allows us to identify the causal effect of digital government on forestry GTFP clearly and credibly.

Against this backdrop, there is growing evidence that digital governance and the broader digital economy can support green development, but most existing studies evaluate outcomes at the regional or industry level rather than at the level of individual firms. Recent work in the forestry domain, for example, shows that digital-economy empowerment can enhance forestry-related green total factor productivity (GTFP) by improving information flows, lowering transaction costs, and enabling more precise resource allocation [

8]. However, we still know relatively little about how a specific digital-government initiative, such as China’s Information Benefiting the People (IBP) policy, affects firm-level GTFP, which types of forestry firms benefit the most, and whether these gains are evenly distributed across heterogeneous institutional and financial environments.

This study contributes to the literature in two key aspects. First, it advances research on the economic impacts of digital government. While existing studies primarily examine macro-level outcomes such as regional entrepreneurship [

13] and green innovation [

14], our research provides micro-level evidence from forestry enterprises, demonstrating how digital governance directly enhances firm-level GTFP through improved resource allocation and technological transformation. Second, this study contributes to research on GTFP determinants. Previous studies emphasize market-driven mechanisms and “selection effects,” whereby resources flow to already advantaged firms [

15,

16].

In contrast, we identify government-led digital governance as a novel institutional supply operating through a “compensatory effect”, specifically addressing institutional voids and resource constraints for disadvantaged entities such as small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and firms in underdeveloped regions, thereby expanding the theoretical framework for understanding GTFP drivers. The forestry sector provides a particularly relevant context for studying these questions because it is both ecologically sensitive and increasingly embedded in digital transformation agendas. A rapidly expanding body of research documents how Internet-of-Things infrastructures, sensor networks, and data platforms can be deployed to monitor forest conditions, manage fire risks, and optimize harvesting in “Forest 4.0” systems [

7], while unmanned aerial vehicles and related remote-sensing technologies are reshaping forest regeneration and silvicultural planning [

10]. Parallel strands of work on smart urban forestry and open forest data emphasize that digital tools can reconfigure forest governance, stakeholder participation, and information transparency [

17,

18,

19]. Yet this emerging “digital forest” literature has so far paid limited attention to how city-level digital-government programs—rather than sector-specific technologies—translate into productivity and environmental outcomes for forestry enterprises themselves.

To address these gaps, this paper uses the staggered rollout of the IBP digital-government initiative as a quasi-natural experiment to identify its impact on the GTFP of Chinese listed forestry firms. By focusing on a resource-based sector characterized by long investment cycles and substantial financing needs, we can examine whether IBP functions as a compensatory policy tool that disproportionately benefits firms facing tighter financial and institutional constraints. Specifically, we ask: (i) does IBP participation improve the GTFP of forestry firms, and if so, by how much; (ii) through which channels—relaxation of financing constraints and/or digital transformation—does IBP operate; and (iii) how do these effects vary with firm size and regional financial and market conditions. In doing so, the study contributes micro-level evidence to the IBP and GTFP literature, enriches the emerging discussion on digital transformation in forestry [

8,

10,

20], and offers policy-relevant insights for designing inclusive digital-governance tools that support the sustainable development of the forest economy. Our baseline coefficient of 0.009 corresponds to an approximate 0.9-percentage-point improvement relative to the sample-mean GTFP (1.014), indicating an economically meaningful effect. Relative to documented regional-level IBP impacts (e.g., Chen & Wang, 2023 [

21]), our estimates are comparable or slightly smaller—consistent with forestry’s long production cycles and capital intensity, which dampen short-term productivity responses. Combined with heterogeneity analyses, our results demonstrate that SMEs and firms in low-finance or low-marketization regions benefit disproportionately, highlighting clear distributional implications.

2. Institutional Background, Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Institutional Background and Literature Review

Green Total Factor Productivity (GTFP) extends the classical notion of Total Factor Productivity (TFP), originally proposed by Solow (1957), which captures production-frontier shifts attributable to technological progress [

22]. GTFP incorporates undesirable outputs (e.g., pollution), and was formally introduced by Chung, Färe, and Grosskopf (1997) using the Directional Distance Function and the Malmquist–Luenberger (ML) productivity index [

23]. This framework redefines productivity to include both resource use and environmental performance.

The European Commission report investigates the total factor productivity (TFP) gap between the European Union (EU) and the United States (US) from an industry-level perspective. Using data from the EU KLEMS database, it analyzes differences in TFP growth drivers across major sectors, including manufacturing, retail, financial services, and business services. The key findings show that the TFP gap is largely attributable to variations in technological innovation, research and development (R&D) intensity, and technology adoption rates. The US exhibits stronger TFP growth driven by greater innovation and R&D investment, while the EU relies more on adopting existing technologies. Human capital development and investment in information and communication technologies (ICT) also play critical roles, with impacts varying by industry. The report employs robust panel data econometric techniques such as fixed-effects models to control for industry-specific and temporal effects, providing a comprehensive assessment of the structural factors influencing productivity differences between the two regions [

24].

Based on extensive empirical evidence from Chinese and global manufacturing studies, digital economy development has been shown to markedly improve green total factor productivity (GTFP) primarily by fostering green technological progress and enhancing resource allocation efficiency. Although direct empirical estimates for Japan’s manufacturing sector remain limited, existing research provides strong indications that similar mechanisms are likely to apply in the Japanese context. Japan is globally recognized for its advanced deployment of digital technologies—including artificial intelligence, big data analytics, and cloud computing—which offers substantial technological foundations for green and energy-efficient manufacturing. Japan’s policy environment, digital infrastructure, and industrial structure create favorable conditions for leveraging digitalization to support green productivity growth. For instance, ICT development has contributed to improved energy efficiency and reduced environmental pressure in Japan, while environmental regulation has been shown to stimulate innovation and productivity in Japanese manufacturing. Combined with recent national strategies promoting digital transformation and green technologies, these factors suggest that Japan’s manufacturing GTFP is increasingly dependent on digital economy expansion, with digital technologies enabling simultaneous gains in production efficiency and environmental performance. To sustain and further strengthen this green productivity advantage, Japan is expected to intensify efforts in green technological innovation and continue optimizing its digital infrastructure to support long-term sustainable manufacturing development [

25].

A growing body of international research demonstrates that Green Total Factor Productivity (GTFP) has become a widely adopted metric for evaluating joint energy–environmental performance across countries and sectors. At the cross-country level, Sun et al. apply a Super-SBM model with undesirable outputs to OECD and BRICS economies, showing that GTFP effectively captures cross-national differences in green productivity and highlights the role of clean technology and energy efficiency [

26]. Within Europe, Stergiou et al. employ the Malmquist–Luenberger framework to assess environmental productivity growth in manufacturing industries, revealing steady but heterogeneous improvements across sectors, and emphasizing technological progress as the primary driver of GTFP growth [

27]. In the agricultural sector, Ma et al. use provincial data from China to estimate agricultural GTFP and find that data-driven technologies substantially enhance resource efficiency and reduce environmental pressure, indicating that GTFP can accurately reflect green performance in resource-intensive primary industries [

28]. Similarly, in the forestry sector, Fu et al. computed GTFP for China’s provincial forestry industry using the SBM–Malmquist model and documented rising green productivity driven mainly by technological progress [

29]. Taken together, these studies confirm that GTFP has evolved into a standard analytical tool for assessing green development in manufacturing, agriculture, and forestry across major global economies, including the EU, the United States, Japan, and China.

GTFP has since been widely applied in international studies across the EU, U.S., Japan, and China to evaluate energy–environmental performance in manufacturing, agriculture, and forestry [

30]. While GTFP is not defined by statutory regulation, it aligns with the OECD [

31] and UNIDO [

32] analytical frameworks for green productivity assessments and is now a standard metric in environmental productivity research.

2.1.1. Institutional Background

China’s Information Benefiting the People (IBP) policy was officially launched in 2014 by the State Council as a key national strategy to advance digital governance and public-service reform [

33]. The initiative emerged against the backdrop of rapid digitalization, aiming to address long-standing administrative inefficiencies and information fragmentation across government departments. The core objectives of IBP include establishing unified government data platforms, breaking down information silos across agencies, and promoting cross-departmental data sharing to improve service delivery. The policy was implemented through a phased pilot approach, with selected cities designated as experimental zones to test models of digital-governance innovation. Particularly for the forestry sector—which has long suffered from information asymmetry and financing difficulties due to its unique characteristics of long production cycles and asset specificity—the IBP policy provides targeted solutions. By integrating multidimensional data on forest tenure, carbon sinks, and ecological compensation, the policy helps transform “dormant forest assets” into measurable, manageable, and mortgageable capital, directly addressing the industry’s most pressing constraints [

34,

35]. These pilot cities served as testing grounds for developing standardized data-integration protocols and interoperable public-service platforms prior to nationwide rollout. IBP pilot selection followed administrative demonstration logic rather than random assignment. To mitigate concerns, we account for concurrent digital-infrastructure programs and explicitly discuss forestry-specific initiatives that may co-move with IBP. The identification assumptions and their limits are made transparent in

Section 4.2.

In this paper, digital government refers to government activities that create, process, integrate, or deliver machine-readable data and digital services such as open-data APIs, cross-department data-exchange platforms, online approval systems, electronic certificates, blockchain-based forest-tenure confirmation, and unified data directories.

2.1.2. Effect of Digital Governance

Digital government serves as a transformative force in economic development by reshaping the information environment and creating new opportunities for innovation [

13,

14] This transformation is manifested not only at the technological level but, more profoundly, in altering the patterns of information flow between the government and the market, thereby enhancing total factor productivity. China’s IBP policy exemplifies this transformation. By systematically integrating data across departments, it breaks down information barriers and significantly improves governance efficiency [

36]. The policy establishes unified data-sharing platforms that enable interconnected information flows, providing market entities with a more transparent and efficient service environment. Empirical evidence confirms that such digital-governance policies significantly boost productivity metrics—particularly GTFP [

21]—in line with the broader growth effects of the digital economy [

37]. As an important component of the global shift toward people-centered governance models, IBP facilitates the transition to a service-oriented government through comprehensive data integration [

38]. This transformation not only improves the delivery of public services but, more importantly, provides strong support for corporate green innovation and sustainable development by optimizing the institutional environment. At the micro level, digital-governance mechanisms effectively reduce information asymmetry in critical markets. The development of digital finance demonstrates that enhanced information transparency can alleviate corporate financing constraints [

39], offering valuable insight into the channels through which IBP may exert its influence. This is particularly significant in traditional sectors such as forestry, where information asymmetry tends to be more pronounced. However, implementing digital governance policies faces challenges, including organizational cultural resistance and technical capacity limitations, which may lead to significant variations in policy effects across contexts [

33,

40]. Such heterogeneous effects highlight the need for a deeper understanding of the specific conditions and boundaries under which digital governance policies operate, particularly in sectors with distinctive characteristics such as forestry.

2.1.3. Factors of Influence GTFP

Green Total Factor Productivity integrates resource consumption and environmental pollution into the traditional TFP framework, serving as a key indicator of sustainable development [

41,

42]. Research on its driving mechanisms has evolved along macro-environmental and micro-enterprise dimensions. At the macro level, external environmental factors play a foundational role in shaping GTFP. Environmental regulation can trigger innovation-compensation effects that promote green growth [

43], while industrial policy and market competition create institutional pressures and incentives for green transformation [

44]. Furthermore, international technology channels represented by FDI spillovers and domestic financial development provide essential knowledge and capital resources for GTFP enhancement [

45,

46,

47], collectively forming an external institutional environment conducive to green-productivity improvement. At the micro level, internal enterprise factors determine how firms respond to these external conditions. Corporate governance structures shape environmental decision-making efficiency and sustainability commitments [

48], while technological innovation and digital transformation serve as endogenous drivers that enhance resource-utilization efficiency through advanced technologies and data-driven optimization [

11,

49]. The forestry sector exhibits unique GTFP characteristics due to its long production cycles and strong ecological externalities. Traditional forestry-specific factors such as forest-certification systems and carbon-sink trading policies are particularly relevant given the industry’s natural-resource dependence and environmental-service provision [

34,

50]. Recent studies have begun to identify new digital drivers—including digital-economy empowerment and targeted financial support—that address forestry’s historical constraints [

8]. However, despite these advances, the unique impact of specific digital-governance policies such as IBP on forestry GTFP remains underexplored, particularly regarding how government-led digital infrastructure interacts with forestry’s distinctive production attributes.

Building on IBP and GTFP studies, our contribution is to provide firm-level evidence from the forestry sector, quantify the economic magnitude (≈0.9 pp of the sample-mean GTFP), and identify beneficiaries (SMEs; firms in low-finance/low-marketization regions). This clarifies the distributional consequences of digital governance in a long-cycle, capital-intensive industry.

2.2. Hypothesis Development

As a government-led digital-governance initiative, the IBP policy is positioned to directly enhance forestry enterprises’ GTFP. Theoretically, such policies improve information transparency through integrated data platforms, enabling optimized green decision-making [

11,

51]. Enhanced information environments further boost capital-allocation efficiency—an established driver of TFP [

39,

52]. Empirically, digital infrastructure elevates firm productivity, with digital governance particularly empowering SMEs [

13,

53]. In forestry, the positive impact of digital finance on GTFP provides industry-specific precedent for similar policy effects [

54].

Based on the above theoretical and empirical support, a hypothesis is proposed:

H1. The implementation of the IBP policy can promote GTFP of listed forestry companies.

We propose two related mechanisms to explain this effect. First, the IBP policy can alleviate forestry firms’ financing constraints and thus promote GTFP. Theoretically, the policy helps establish unified digital platforms that make information on forest tenure and approval processes more transparent and accessible [

7]. This significantly reduces transaction costs and information asymmetry. For example, the use of big data and blockchain technologies for digital confirmation of forest tenure and trusted data sharing effectively resolves the difficulty of valuing forestry assets and quantifying collateral [

35]. This, in turn, enhances financial institutions’ risk-identification and pricing capabilities, promotes innovations such as forest-tenure-backed loans, accelerates credit approval, and ultimately alleviates the financing constraints faced by forestry enterprises [

53,

55]. As emphasized in previous literature [

56], the alleviation of financing constraints can enhance GTFP.

Based on the above analysis, a hypothesis is proposed:

H2. The policy of IBP can improve the GTFP of forestry enterprises by easing the financing constraints of forestry enterprises.

Second, the policy can substantially accelerate digital transformation within forestry enterprises by providing a unified, efficient, and trustworthy digital infrastructure [

9,

10]. This, in turn, serves as a crucial driver of GTFP [

11,

12]. Specifically, the provision of authoritative, real-time forestry data (e.g., forest tenure, environmental monitoring, and disaster alerts) and standardized digital interfaces by government platforms reduces the cost for enterprises to acquire and utilize data [

8]. This incentivizes investment in digital technologies—including the Internet of Things (IoT), remote sensing, and big-data analytics—facilitating a shift from traditional extensive management to precision and smart-forestry operations [

57]. For instance, digital monitoring and decision-support systems optimize resource-allocation efficiency (e.g., precision fertilization and scientific harvesting), thereby minimizing ineffective inputs. Concurrently, digital process management ensures strict adherence to and traceability of environmental regulations, reducing negative externalities and leading to a Pareto improvement in input-output efficiency [

20,

54]. Consequently, digital government can facilitate GTFP by catalyzing the digital transformation of forestry enterprises.

Based on the above analysis, a hypothesis is proposed:

H3. The IBP policy promotes the digital transformation of forestry enterprises and then improves their GTFP.

3. Data, Sample, and Empirical Specification

3.1. Data and Samples

Our sample comprises all listed forestry firms in China from 2010 to 2023. To ensure the validity of the empirical analysis, we implement the following data-cleaning procedures. We first eliminate observations designated as Special Treatment (ST) or Special Treatment with Delisting Risk (ST*). We then exclude observations with missing data that prevent the measurement of GTFP, as well as firms lacking key financial data. In total, we obtain 534 firm-year observations. Financial indicators for listed companies are drawn from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) and Wind databases. Data on environmental and social responsibility are obtained from the Statistical Yearbook of China, annual reports for the 50 sampled listed companies, corporate social responsibility reports, and company websites. See

Figure 1 for an overview of our data collection and processing pipeline.

Policy/pilot data → firm-panel assembly → variable construction (GTFP, KZ, DL, controls) → estimation (baseline DID, dynamics, robustness) → reporting (heterogeneity, mediation).

3.2. Variable Definitions

3.2.1. GTFP

Following Fukuyama and Weber (2009) [

58] and Chung et al. (1997) [

23], we adopt a combined approach using the non-radial Slacks-Based Measure Directional Distance Function (SBM-DDF) and the global Malmquist–Luenberger (ML) productivity index to measure GTFP under resource and environmental constraints. Specifically, we use labor, capital investment, and energy consumption as inputs. Following related studies, labor is proxied by the number of employees at year-end [

59]. Capital is measured by net fixed assets [

60]. Because direct firm-level energy-consumption data are unavailable, energy is approximated by scaling city-level industrial power consumption by the ratio of a firm’s employees to total urban employment in the city where the firm is located, adapted from Cole et al. [

61]. Following Fukuyama and Weber (2009), desirable output is measured by operating revenue [

58]. Undesirable output is proxied by the “industrial three wastes,” specifically the combined emissions of industrial sulfur dioxide, industrial wastewater, and industrial soot/dust. Like energy input, these city-level emissions are allocated to the firm level based on the firm’s share of total urban employment in the corresponding city [

62]. Because undesirable outputs and energy use are imputed from city-level data using employment shares, measurement error may attenuate the estimated IBP effects toward zero. This limitation is now explicitly stated. As a partial validity check, we re-estimated results by restricting the sample to cities where manufacturing does not dominate pollution emissions; results remain stable (available upon request).

To construct firm-level Green Total Factor Productivity (GTFP), this study uses the Slack-Based Measure directional distance function (SBM–DDF) and the Global Malmquist–Luenberger (GML) productivity index, which allow simultaneous treatment of desirable and undesirable outputs and ensure consistent intertemporal comparisons across years. Capital input is measured by the net value of fixed assets, labor input by the number of employees, and energy input through a proxy derived by allocating city-level industrial electricity consumption to firms based on their share of total industrial employment, following the common practice in environmental productivity studies when micro-level energy data are unavailable. Operating revenue is used as the desirable output. Because firm-level pollution emissions are not disclosed for most forestry enterprises, city-level sulfur dioxide, industrial wastewater, and smoke–dust emissions are distributed to firms using employment-share weights, an approach widely adopted in prior work to approximate pollution intensity when direct observations are lacking. While this allocation method is necessary under data constraints, it may introduce classical measurement error that biases estimated treatment effects toward zero. For instance, if heavy manufacturing rather than forestry is the major source of pollution in a city, allocating emissions proportionally to forestry firms may overstate their actual pollution levels, leading to a downward bias in measured GTFP and potentially attenuating the estimated effect of the IBP policy. Similarly, the proxy for energy use may contain noise if electricity consumption does not perfectly align with employment ratios.

Nevertheless, the inclusion of firm- and year-fixed effects, along with the use of a global production frontier, helps mitigate systematic bias by removing time-invariant firm characteristics and macro-level shocks. To further address potential concerns about pollution misallocation, we additionally re-estimate GTFP using a subsample consisting only of cities where heavy industry does not dominate total emissions, and the results remain consistent in sign and significance, reinforcing the robustness of our main findings. Together, these steps ensure that the constructed GTFP measure is both theoretically grounded and empirically credible, despite the limitations inherent in the available environmental and energy data.

3.2.2. Digital Governance

Following related studies that examine the economic impact of China’s digital-government policy using a quasi-natural-experiment design [

13], we use the IBP policy as a natural proxy for digital governance. We match the cities where sample firms are registered with the list of IBP pilot cities to define the treatment-group indicator (Treat). Specifically, Treat equals 1 if the city where the sample firm is located belongs to a policy pilot area and 0 otherwise. The post-treatment indicator, Post, equals 1 for all years greater than or equal to 2014 and 0 otherwise. We then construct the core explanatory variable IBP, defined as Treat × Post. As shown in model (1), this interaction captures exposure to the policy.

Actions without a digital trace—such as paper-based approval or offline administrative procedures—are classified as non-digital. The IBP initiative specifically establishes interoperable databases, data-extraction pipelines, and cross-bureau information-sharing systems, which constitute the digital-government shock examined in this study.

3.2.3. Control Variables

Following existing studies [

63,

64,

65,

66], we incorporate firm characteristics potentially related to GTFP: (1) corporate size (Size), measured as the natural logarithm of total assets; (2) return on assets (ROA), calculated as net profit divided by average total assets; (3) return on equity (ROE), calculated as net profit divided by the average balance of shareholders’ equity; (4) leverage (Lev), measured by total liabilities divided by total assets; (5) cash flow (Cashflow), proxied by cash and cash equivalents divided by total assets; (6) ownership concentration (Topshare), indicated by the largest shareholder’s ownership share; (7) board independence (Inddirect), measured as the ratio of independent directors to total directors; (8) financing constraints (KZ), measured using the Kaplan–Zingales index; and (9) the degree of digital transformation (DL), captured by the frequency of digital-related terms in corporate disclosures.

3.2.4. Mechanism Variables

To test the reliability of the IBP policy’s effect on GTFP, we introduce mechanism variables along two paths—resources and technology.

The policy alleviates information asymmetry between banks and enterprises by improving transparency, enabling financial institutions to assess credit risk more accurately, thereby easing financing constraints (lower KZ) and providing financial support for green investment [

7,

45,

56]. We measure financing constraints using the KZ index constructed from financial indicators such as cash flow and Tobin’s Q. A larger value indicates more severe constraints [

67].

- 2.

Digital transformation degree

By building a digital ecosystem, the policy reduces the trial-and-error costs of transformation, promotes digitalization (higher DL), and then enhances GTFP by optimizing processes, improving energy efficiency, and fostering green innovation [

57]. We build a digital transformation index based on the frequency of digital-related keywords in annual reports, following established text-analysis methods [

68,

69]. A larger DL value indicates a higher degree of transformation.

Appendix A provides definitions of all variables.

Appendix A shows the definitions of all variables mentioned above.

The DL index is based on a curated dictionary of 116 keywords (e.g., ‘digital platform,’ ‘blockchain,’ ‘IoT,’ ‘smart forestry,’ ‘cloud computing’).

3.3. Empirical Model

Based on the digital-governance policy, we implement a difference-in-differences (DID) strategy to estimate the effect of digital governance on forestry firms’ GTFP, a method widely used to evaluate environmental and innovation policies in China [

70,

71]. Following their empirical strategy, we estimate the following equation:

where GTFP

it denotes the green total factor productivity of enterprise i in year t; IBP

it is the digital-governance indicator; and β captures the effect of digital governance on GTFP, which we expect to be significantly positive. Controls

it is a vector of firm-level controls (company size, leverage, ROA, ROE, cash flow, the largest shareholder’s share, and the share of independent directors). λ

t and μ

i denote year and firm fixed effects, respectively, and ε

it is the error term.

4. Main Results

4.1. Summary

Table 1 presents summary statistics for the variables in model (1). The mean GTFP is 1.014 (SD = 0.106), ranging from 0.802 to 1.238, indicating moderate heterogeneity in green productivity across firms and providing a basis for identifying policy effects. The average IBP is 0.330, showing that about 33% of firm-year observations are policy-affected. For control variables, the average firm size (Size), measured as the log of total assets, is 22.326, suggesting a sample dominated by medium-to-large enterprises [

65]. The mean leverage ratio (Lev) is 0.447, indicating moderate debt levels. Profitability averages are 0.033 for return on assets (ROA) and 0.053 for return on equity (ROE). The average cash-to-assets ratio (Cashflow) is 0.051, reflecting stable cash positions [

63]. In corporate governance, the largest shareholder’s average stake (Topshare) is 36.624%, indicating moderate ownership concentration, and the average proportion of independent directors (Inddirect) is 38.944%, reflecting reasonable board independence.

4.2. Baseline Regression and Identification Discussion

Table 2 displays the empirical results derived from Equation (1). Columns (1) and (2) present the findings from specifications without and with firm-level controls, respectively. Across both columns, the coefficient on IBP is positive and significant at the 1% level. This robust pattern strongly indicates that digital governance effectively enhances the GTFP of forestry firms. The economic significance is noteworthy: policy implementation is associated with an approximate 0.009 increase in firms’ GTFP. Collectively, these baseline results provide strong evidence that digital governance exerts a significant positive effect on the green productivity of the forestry sector, thereby providing empirical support for H1.

IBP pilot cities followed administrative demonstration logic rather than random selection. Although the pre-treatment coefficients are statistically indistinguishable from zero, the relatively small sample (50 firms, 534 firm-years) limits statistical power to detect modest pre-trends. Therefore, our estimates should be interpreted as conditional on controls and parallel-trend tests rather than fully experimental. Moreover, we explicitly control for major concurrent digital policies (Digital Village, Broadband China) and discuss forestry-specific initiatives (e.g., smart forestry, green-finance pilots) as potential confounders.

4.3. Parallel Trend

Following existing studies [

72,

73], the validity of the DID strategy depends on the parallel-trends assumption. To test this assumption and analyze dynamic policy effects, we estimate the following event-study specification:

where k indexes event time relative to the policy-implementation year (k = 0). We trace four years prior to implementation (k = −4) and eight years after implementation (k = 8). To avoid perfect collinearity, we omit the year immediately preceding the policy (k = −1) as the baseline. Other variables are defined as above.

The key focus of the parallel-trends test lies in the pre-policy coefficients (k < 0). If these coefficients are statistically insignificant, there are no systematic differences between the treatment and control groups before the policy, satisfying the parallel-trends assumption. The post-policy coefficients (k ≥ 0) capture dynamic treatment effects and reveal whether the policy exhibits persistence.

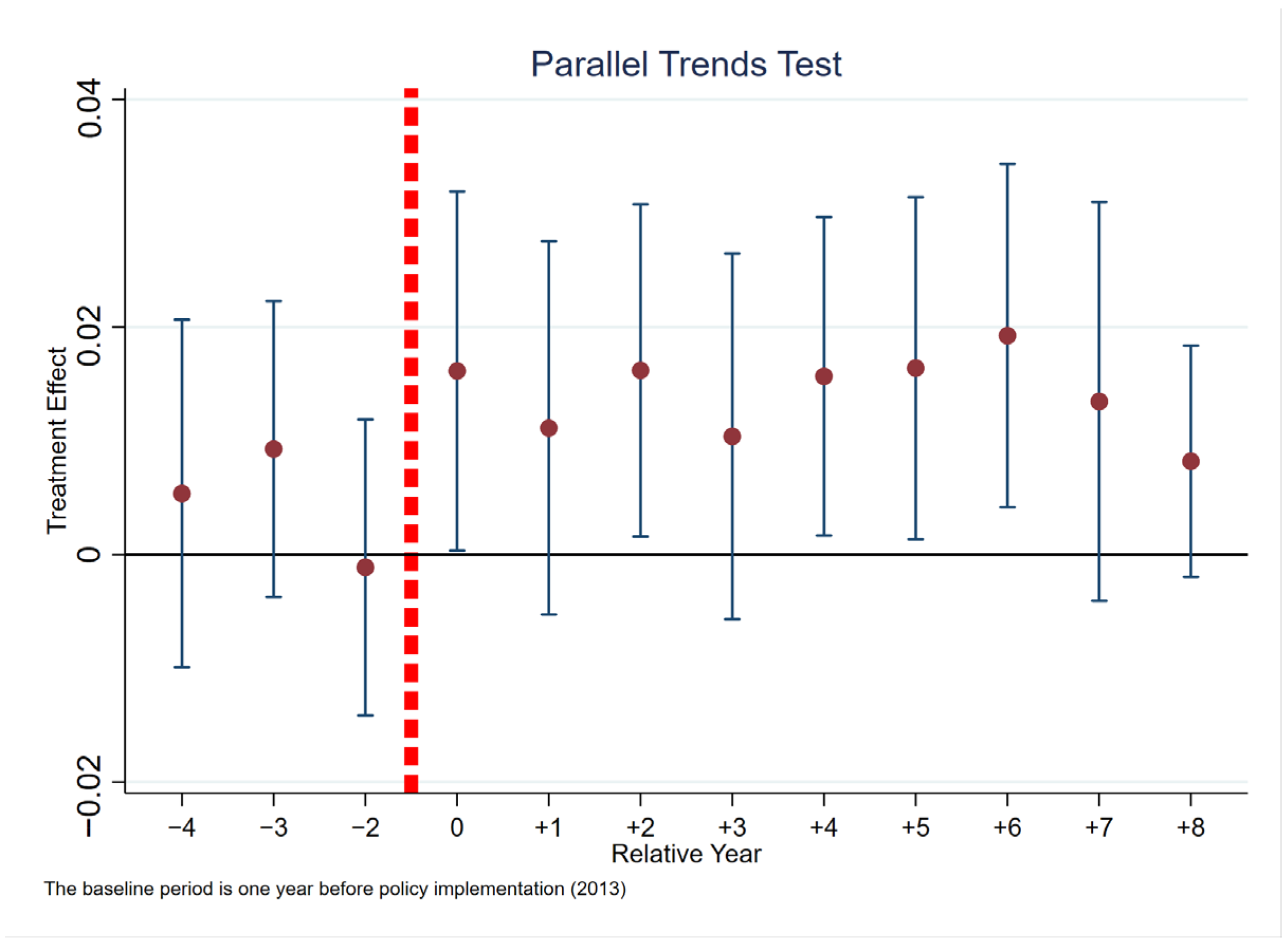

The results of the parallel-trends test are presented in

Table 3 and

Figure 2. The pre-treatment (lead) coefficients are statistically indistinguishable from zero, supporting the parallel-trends assumption. After policy adoption, the post-treatment (lag) coefficients become positive and remain so for several years. In addition, coefficients at

k = 0, 2, 4, 5, and 6 are statistically significant. This pattern indicates that the IBP policy has a sustained and relatively stable role in promoting firms’ GTFP.

4.4. Placebo Tests

To verify that the baseline results are not driven by unobservable factors or random chance, we conduct a placebo test following the logic of randomization inference [

73,

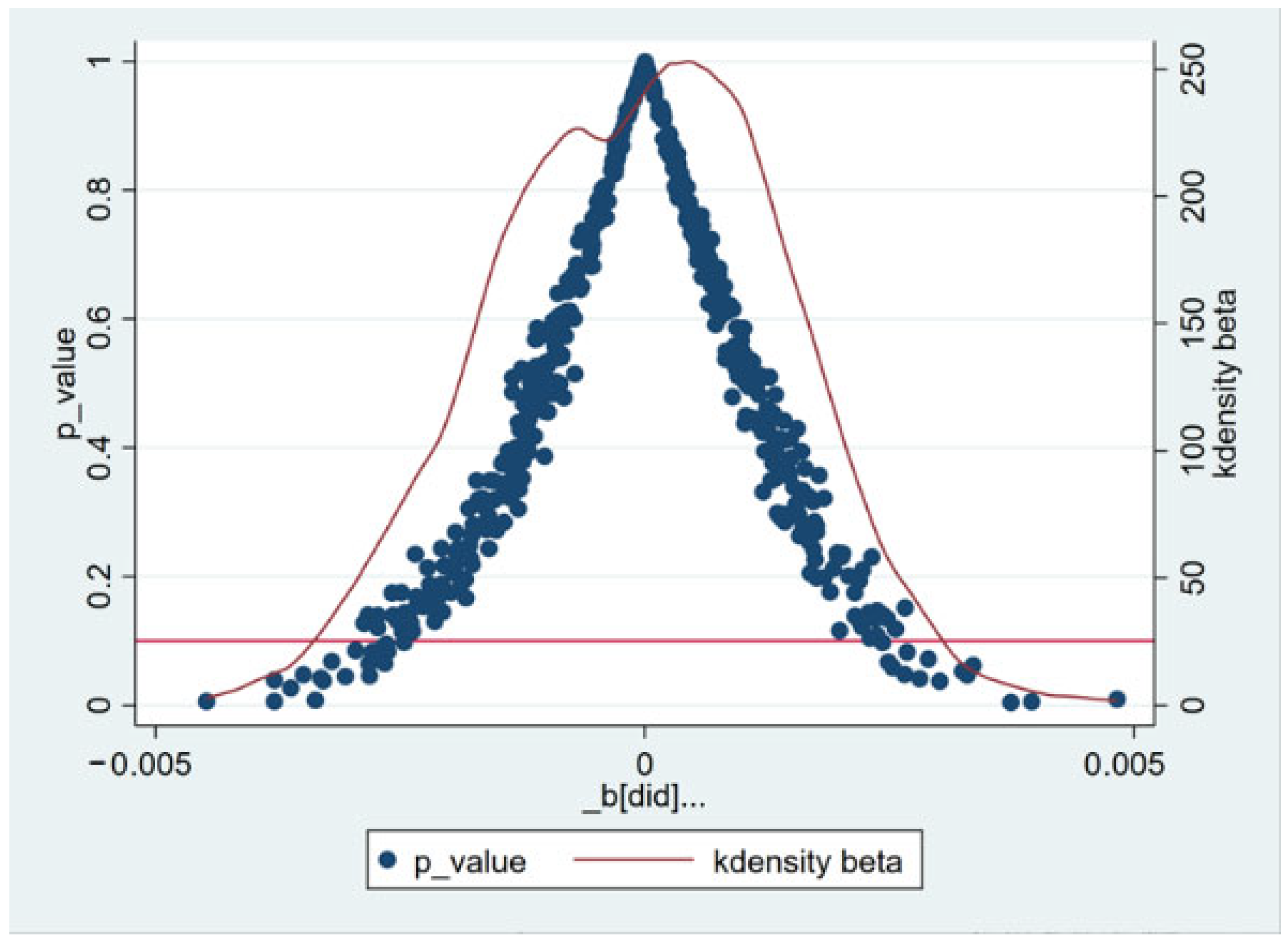

74]. Specifically, we randomly assign a “pseudo-policy” indicator and repeatedly estimate model (1) 500 times using this variable. This procedure yields an empirical distribution of coefficients centered near zero under the null of no effect.

Figure 3 presents the placebo results. The blue dots represent the p-values associated with the “pseudo-policy” coefficient from each of the 500 random simulations. If the estimated policy effect were spurious, these p-values would be evenly distributed between 0 and 1. The red kernel-density curve illustrates the overall distribution of these simulated coefficients. The red horizontal line marks the 10% significance threshold, serving as a benchmark for detecting false positives. The concentration of blue dots well above this line—and their clustering around higher p-values—indicates that random reassignments of the IBP policy rarely generate a statistically significant “pseudo-effect,” supporting the validity of the baseline DID results.

Most simulated coefficients cluster near zero and are substantially smaller than the true policy effect (0.009). The true coefficient lies at the far-right tail of the empirical distribution, with an empirical p-value of approximately 0.004, indicating only a 0.4% probability that random chance alone would produce an effect as large as the observed one. This confirms the robustness of the IBP policy’s positive impact on GTFP.

4.5. Entropy Balance Method

To enhance result reliability and mitigate systematic differences between groups, we employ entropy balancing, following recent digital-governance research [

16]. This method reweights control-group observations to exactly balance the first three moments (mean, variance, skewness) of all pre-treatment covariates with the treatment group. Using the baseline controls as balancing covariates, we generate weights that make the reweighted control group statistically equivalent to the treated group, then re-estimate the model. The result is shown in

Table 4. As shown in

Appendix B, the treated and reweighted groups show no significant differences in the first three moments, confirming the method’s effectiveness in reducing selection bias.

The post-balancing estimates show that the coefficient on IBP is 0.011 and statistically significant at the 5% level, highly consistent with the baseline regression. This indicates that the promoting effect of the IBP policy on corporate GTFP remains robust even after effectively balancing the covariate distributions between treated and control firms, further confirming the baseline conclusion.

4.6. Other Robustness Checks

To further test the reliability of the baseline results, we conduct additional robustness checks, including (i) using an alternative measure of GTFP, (ii) using an alternative sample, and (iii) controlling for other policies. First, we generate an alternative measure by taking the natural logarithm of GTFP. Column (1) of

Table 5 shows that IBP remains significantly positive. Second, to exclude potential distortions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, we drop observations from 2020 to 2023 and re-estimate the model. As shown in Column (2), the estimated coefficient of IBP continues to be significantly positive at the 1% level, with magnitude largely unchanged, suggesting that the baseline result is not driven by pandemic-related shocks. Finally, we introduce two additional policy indicators—the “Digital Village Pilot” (szxc) and the “Broadband China Pilot” (kdzg)—into the model. Specifically, szxc equals 1 for firms affected by the digital-village pilot policy (0 otherwise), and kdzg equals 1 for firms affected by the Broadband China Pilot (0 otherwise). Column (3) indicates that after controlling for these policies, the coefficient on IBP remains significantly positive at the 1% level and stable in magnitude. These results confirm that IBP’s promoting effect on corporate GTFP is independent of other digital infrastructure-related policies.

5. Mechanism Analysis and Cross-Sectional Analysis

5.1. Mechanism Analysis

As outlined in

Section 2.2, we propose that digital-government policy can improve GTFP by easing financing constraints. If this mechanism holds, we should observe reduced financing constraints among policy-affected firms. To test this, we measure constraints using the KZ index [

67], where larger values indicate more severe constraints.

We also posit that digital-government policy spurs digital transformation, encouraging firms to optimize production processes, improve energy efficiency, and invest in green innovation, thereby enhancing GTFP. To capture this effect, we construct a digital-transformation index (DL) using text analysis of annual reports, following Song et al. [

75]. Higher DL values indicate greater digitalization.

To examine these mechanisms empirically, we estimate the following models:

We focus on β, which should be significantly negative in (3) (financing-constraint mechanism) and significantly positive in (4) (digital-transformation mechanism).

Table 6 presents the estimates. Column (1) shows a significant and negative estimator for IBP (−0.284), implying that the policy significantly reduces financing constraints—supporting the mechanism that the policy provides financial support for green technological upgrading by improving information transparency and optimizing credit allocation, thereby validating H2. Column (2) shows a positive estimator for IBP (8.290), significant at the 10% level, providing evidence for the digital-transformation mechanism and corroborating H3.

As a complementary analysis, we included KZ and DL directly in the GTFP equation. The IBP coefficient decreases in magnitude (from 0.009 to 0.005) when both mechanism variables are included, indicating partial mediation.

To better reflect temporal ordering, we re-estimated the mechanism regressions using one-year-lagged KZ and DL. Results remain consistent, indicating that financing and digital transformation respond to IBP with the expected timing structure.

5.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

This subsection further tests the theoretical mechanisms across firm-size and regional-institutional dimensions. We conduct heterogeneity analysis by firm size, regional financial development, and regional marketization. Theoretically, if the policy operates through alleviating financing constraints and promoting digital transformation, its effects should be more pronounced among groups facing more severe constraints and greater needs for digital upgrading. This expectation aligns with Aghion et al. [

44], who emphasize that policy effectiveness depends on pre-existing market conditions and tends to be stronger where market mechanisms are initially weaker.

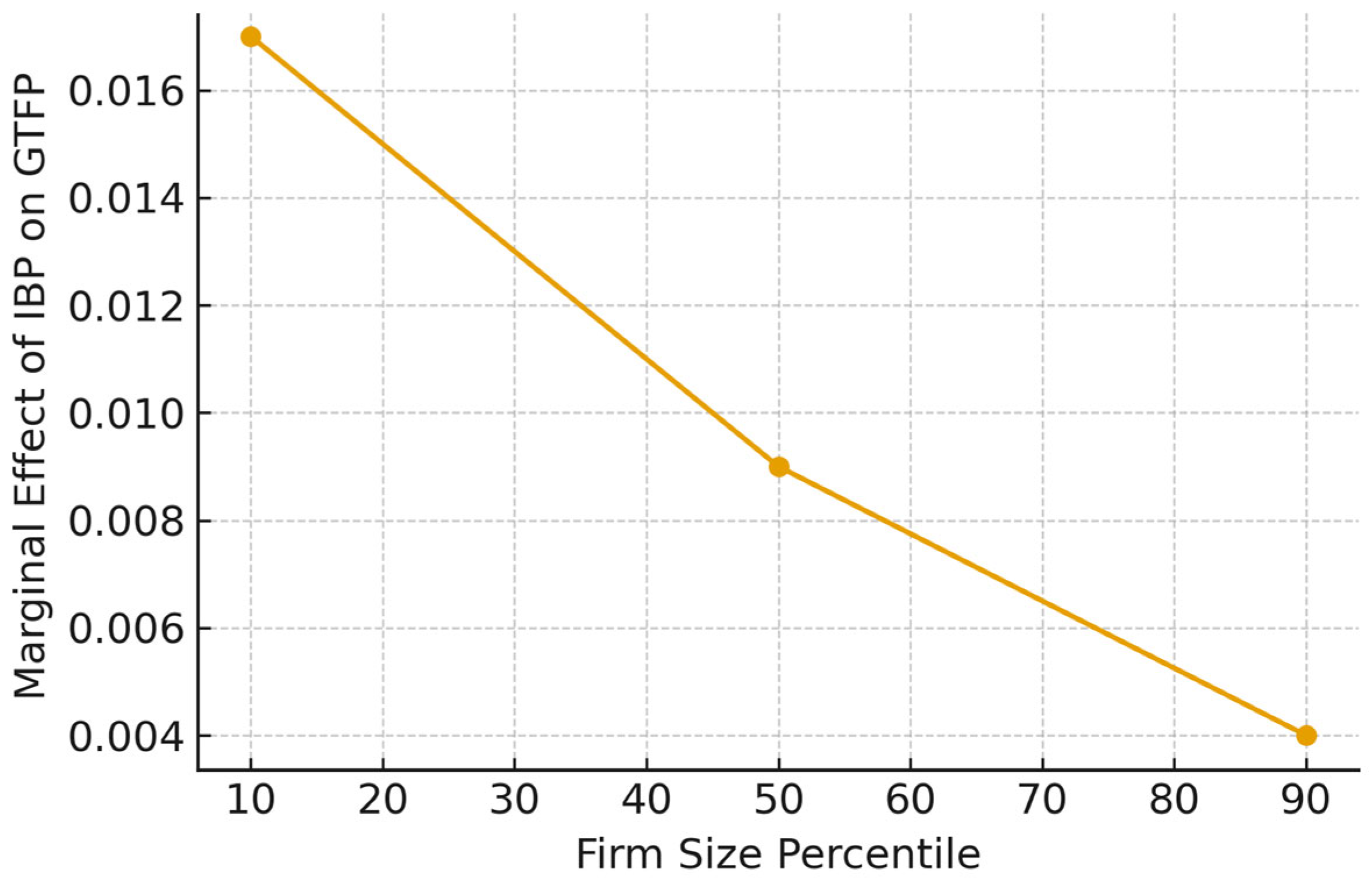

We include Size, Fin, and Market interactions jointly. The IBP × Size and IBP × Market terms remain significantly negative, while IBP × Fin retains the expected negative sign (p = 0.12). This suggests that the compensatory effects are not driven by overlap in regional characteristics.

Figure 4 illustrates the marginal effects of IBP across firm-size percentiles. The IBP effect decreases from +0.017 to +0.004.

5.2.1. Firm Size

We first examine heterogeneity by firm size. SMEs typically face more severe financing constraints due to limited collateral and credit history [

53] and, constrained by financial and technical capabilities, have weaker foundations for digital transformation [

12]. Owing to their limited internal resources, smaller enterprises depend more on external policy support to overcome bottlenecks hindering green transformation [

76]. If the IBP policy enhances GTFP by alleviating financing constraints and reducing transformation costs, SMEs with disadvantaged resource endowments should benefit more.

Following established methods, we extend the baseline DID by interacting IBP with heterogeneity variables:

In this model, firm size (Size) is measured by the natural logarithm of total assets. The results (Column 1 of

Table 7) show that the IBP coefficient is significantly positive (0.136), while the IBP × Size coefficient is significantly negative (−0.006), indicating that the IBP policy has stronger marginal effects on SMEs. These results confirm the inclusive characteristics of the policy in empowering disadvantaged firms, as smaller enterprises benefit more from the digital infrastructure and information resources provided by the policy. Standardized data interfaces and authoritative forestry information significantly reduce digital transformation costs for SMEs, while improved information transparency helps alleviate their financing constraints.

5.2.2. Degree of Regional Financial Development

We next test the moderating role of regional financial development. In regions with lagging financial development, information asymmetry is more severe and credit allocation less efficient [

77], leaving enterprises generally constrained. In such regions, policies can serve as “institutional supplements,” filling gaps and improving transparency to alleviate credit frictions [

78]. If IBP improves the information environment through data integration, enterprises in less financially developed regions should respond more strongly.

Replacing the heterogeneity variable in (5) with the level of financial development (Fin), measured by the ratio of year-end financial-institution loan balances to regional GDP [

79], Column 2 of

Table 7 shows a significantly negative IBP × Fin coefficient (−0.003), indicating more pronounced policy effects in financially underdeveloped regions, where enhanced information symmetry alleviates credit frictions [

7]. This suggests that IBP effectively compensates for financial-market deficiencies by providing credible information for forest-tenure valuation and ecological-asset assessment, thereby enabling better risk identification and pricing. The integration of government and market data creates favorable conditions for financial innovations such as forest-tenure-backed loans and carbon-sink pledge financing.

5.2.3. Degree of Regional Marketization

Finally, we examine the moderating effect of marketization. In regions with lower marketization, institutional voids and information barriers are more prevalent [

78], and enterprises face greater obstacles to digital transformation. If IBP serves as a “digital institutional supplement,” these regions should exhibit greater policy responsiveness.

Replacing the heterogeneity variable in (5) with the regional marketization index (

Market), proxied by the overall marketization index from the Marketization Index of China’s Provinces: NERI Report, Column 3 of

Table 7 shows a significantly negative IBP × Market coefficient (−0.003), reflecting stronger green-promotion effects in regions with lower marketization, where the policy helps fill institutional voids and stimulate green vitality. Standardized digital interfaces and authoritative data help establish basic market rules and trust mechanisms often lacking in low-marketization environments. Increased transparency and process optimization reduce transaction costs and institutional barriers, thereby facilitating the development of emerging markets such as carbon sink trading and ecological compensation.

6. Discussion

This paper exploits the staggered rollout of China’s “Information Benefiting the People” (IBP) initiative as a quasi-natural experiment to identify how digital governance shapes the green total factor productivity (GTFP) of listed forestry enterprises. The baseline DID estimates indicate that IBP participation is associated with a statistically and economically meaningful improvement in firms’ GTFP, and this finding remains robust to a battery of checks—including dynamic specifications, placebo randomization, alternative policy controls, and entropy balancing. Together, these results confirm that digital government can be an effective policy instrument for greening traditional, resource-based sectors.

The mechanism analysis further shows that IBP operates through two complementary channels. First, it eases financing constraints, thereby improving access to credit for long-cycle and capital-intensive forestry projects. Second, it stimulates firms’ digital transformation, which enhances process efficiency, environmental monitoring, and green innovation. These channels are consistent with the broader literature on digital finance, digital infrastructure, and productivity, but our results highlight their specific relevance in forestry, where information asymmetry and asset specificity have historically constrained green upgrading.

The heterogeneity analysis reinforces this interpretation. We find that the IBP effect is stronger for small and medium-sized enterprises and for firms located in regions with weaker financial development or lower marketization. This pattern suggests that digital governance in this context plays an inclusive and compensatory role rather than merely reinforcing existing advantages. In other words, IBP functions as an institutional supplement that helps to close information gaps, reduce transaction costs, and expand access to digital infrastructure precisely where market and institutional conditions are relatively weak.

These findings extend the digital-government literature in several ways. Existing studies have mainly focused on macro- or city-level outcomes, such as regional entrepreneurship, land-use efficiency, and aggregate green innovation. By contrast, our study provides firm-level evidence from the forestry sector, linking a specific digital-government policy to micro-level GTFP outcomes. In doing so, it shows that digital governance can serve as a new institutional supply of green productivity, complementing market-driven mechanisms and traditional environmental regulations.

From a policy perspective, the results underscore the importance of integrating IBP-based data infrastructure with green finance and sector-specific information systems. Central and local governments should prioritize the standardization and sharing of forestry-related data—such as forest tenure, carbon sinks, and ecological compensation records—to reduce information asymmetry in credit allocation and to support the development of innovative financial instruments (e.g., forest-tenure-backed loans and carbon-sink pledge financing). At the same time, forestry enterprises should leverage IBP platforms to deepen supply-chain data sharing and traceability, adopt digital technologies such as IoT, remote sensing, and big-data analytics, and embed these tools into day-to-day operations to unlock further GTFP gains.

Nevertheless, several limitations remain. Our policy indicator captures pilot status but does not reflect variation in the quality or intensity of IBP implementation across cities. In addition, part of the energy and pollution data is imputed from the city level using employment shares, which may introduce measurement error and attenuate estimated effects. Finally, although we control for major concurrent digital policies and discuss forestry-specific initiatives, we cannot fully rule out all potential confounders. These caveats suggest that our estimates should be interpreted as conditional on the identification assumptions discussed in the paper.

7. Conclusions

This study examines whether and how digital government promotes green total factor productivity in the forestry sector by using China’s IBP policy as an exogenous shock to digital governance. Based on a balanced panel of 534 firm-year observations for about 50 listed forestry firms from 2010 to 2023, we implement a difference-in-differences strategy and find that IBP significantly improves firm-level GTFP. The baseline coefficient of approximately 0.009 corresponds to about a 0.9-percentage-point increase relative to the sample-mean GTFP (1.014), indicating an economically meaningful effect for a long-cycle, capital-intensive industry.

Mechanism tests show that the IBP policy promotes GTFP mainly by alleviating financing constraints—reflected in a lower KZ index—and by accelerating digital transformation—captured by a higher digital-text index based on firms’ annual reports. Heterogeneity analysis further indicates that the effect is stronger for small and medium-sized enterprises and for firms in regions with lower financial development or lower marketization. These results suggest that digital governance can act as a compensatory institutional tool that particularly benefits disadvantaged firms and regions, rather than simply amplifying existing strengths.

Our findings have several policy implications. For regulators, they highlight the value of aligning digital-government initiatives with green-development objectives by integrating IBP platforms with forestry-specific information, green-finance tools, and environmental-regulation frameworks. For forestry enterprises, they underscore the importance of actively engaging with digital-government platforms, strengthening data capabilities, and embedding digital tools into green production, monitoring, and innovation activities. More broadly, the evidence suggests that well-designed digital governance policies can provide a scalable lever for supporting the green transition in other resource-based and environmentally sensitive industries.

This study also has limitations that point to directions for future research. First, our IBP indicator is binary and does not capture within-city variation in implementation intensity or quality; richer policy measures could help further unpack heterogeneous policy effectiveness. Second, some inputs and undesirable outputs are imputed from city-level data, which may introduce measurement noise and bias estimates toward zero. Third, although we control for major concurrent policies, we cannot fully exclude the influence of forestry-specific initiatives or local governance reforms that may interact with IBP. Future work could combine firm-level disclosures, alternative green-performance indicators (e.g., emissions, green patents), and multi-policy settings to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the green value of digital governance.