Analysis of Surface Texture Distribution Characteristics of Concrete Substrate and Modeling of Coating Adhesion Strength

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

2.2. Coatings and Coating Methods

2.3. Test Methods

2.3.1. Grinding Test

2.3.2. Roughness Characterization

- (1)

- Interfacial Roughness and Water Absorption

- (2)

- Silica Powder Roughness Index (MTD)

- (3)

- Stylus Roughness Profiling

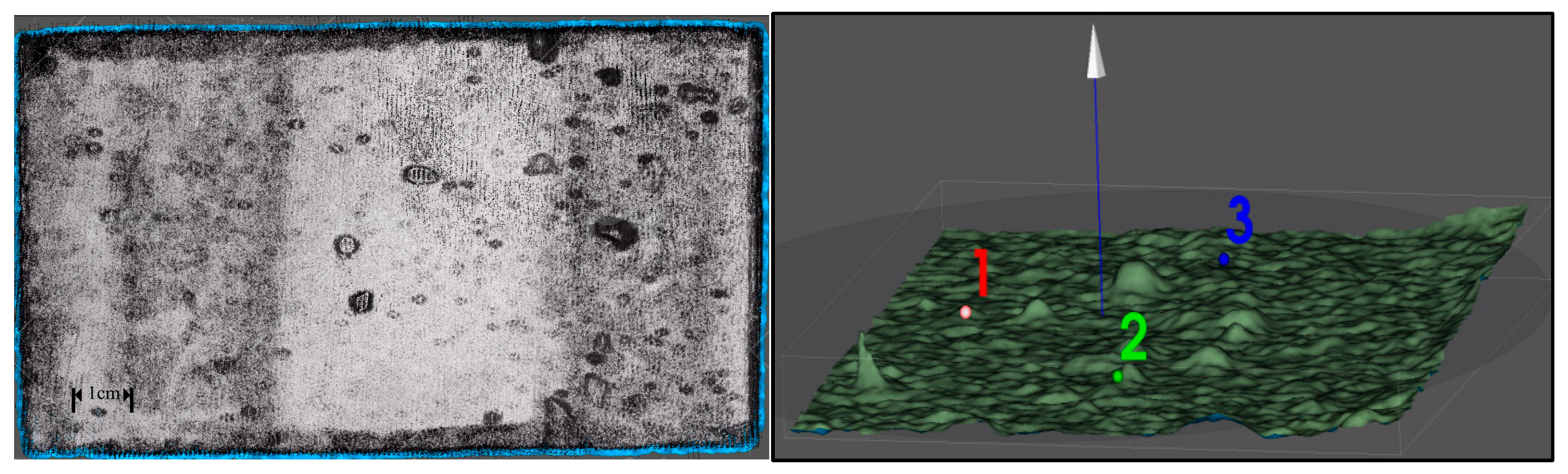

2.3.3. 3D Surface Topography Modeling

2.4. Calculation of 3D Surface Texture Parameters

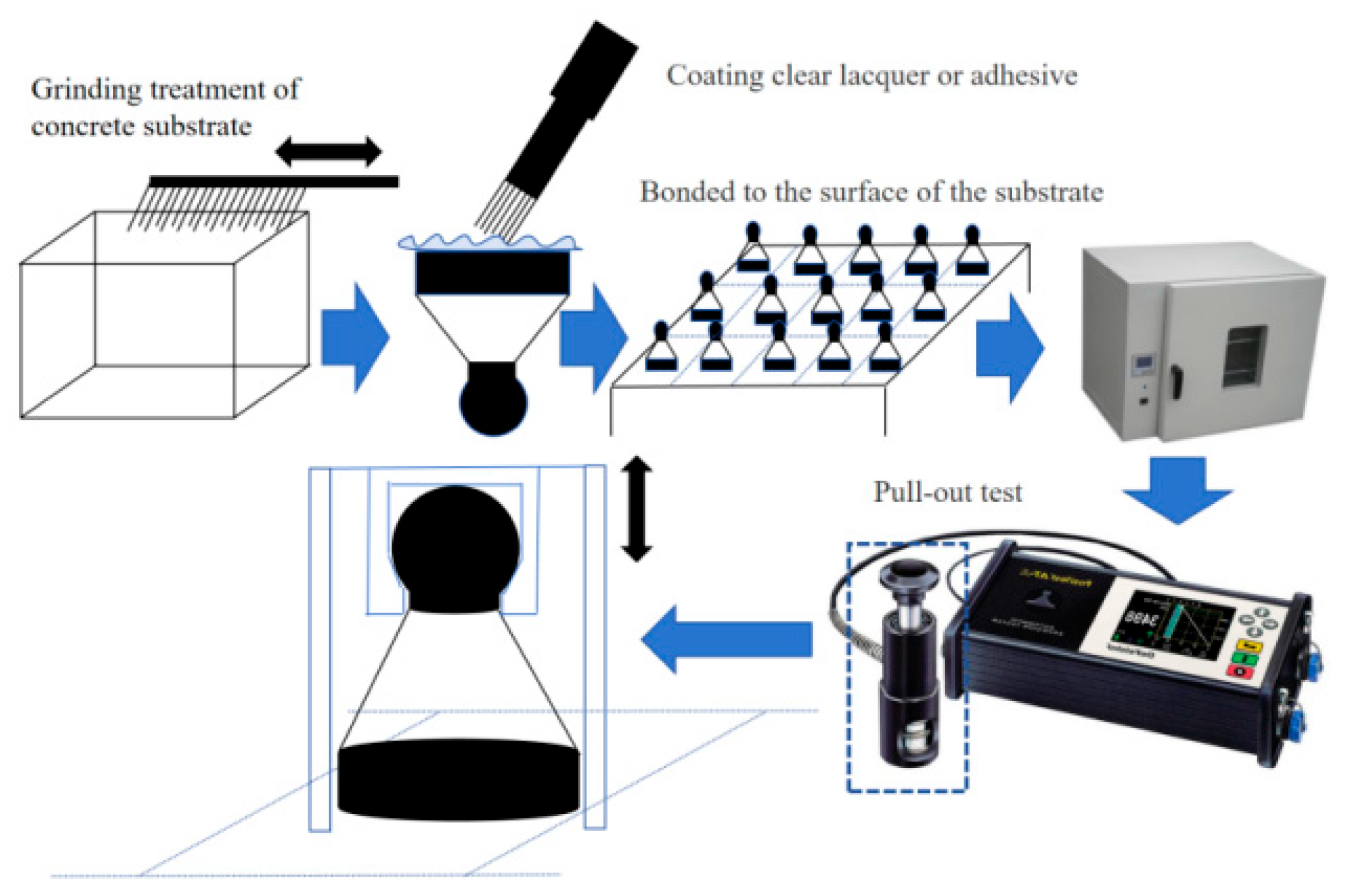

2.5. Pull-Off Strength of Substrate and Coating

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Cement Coatings Morphology

3.1.1. Morphology and Texture of Concrete Under Grinding

3.1.2. Three-Dimensional Morphology of Concrete Substrate Surface

3.2. Relationship Between Surface Texture Parameters and Drawing Strength of Concrete Substrate at Different Temperatures

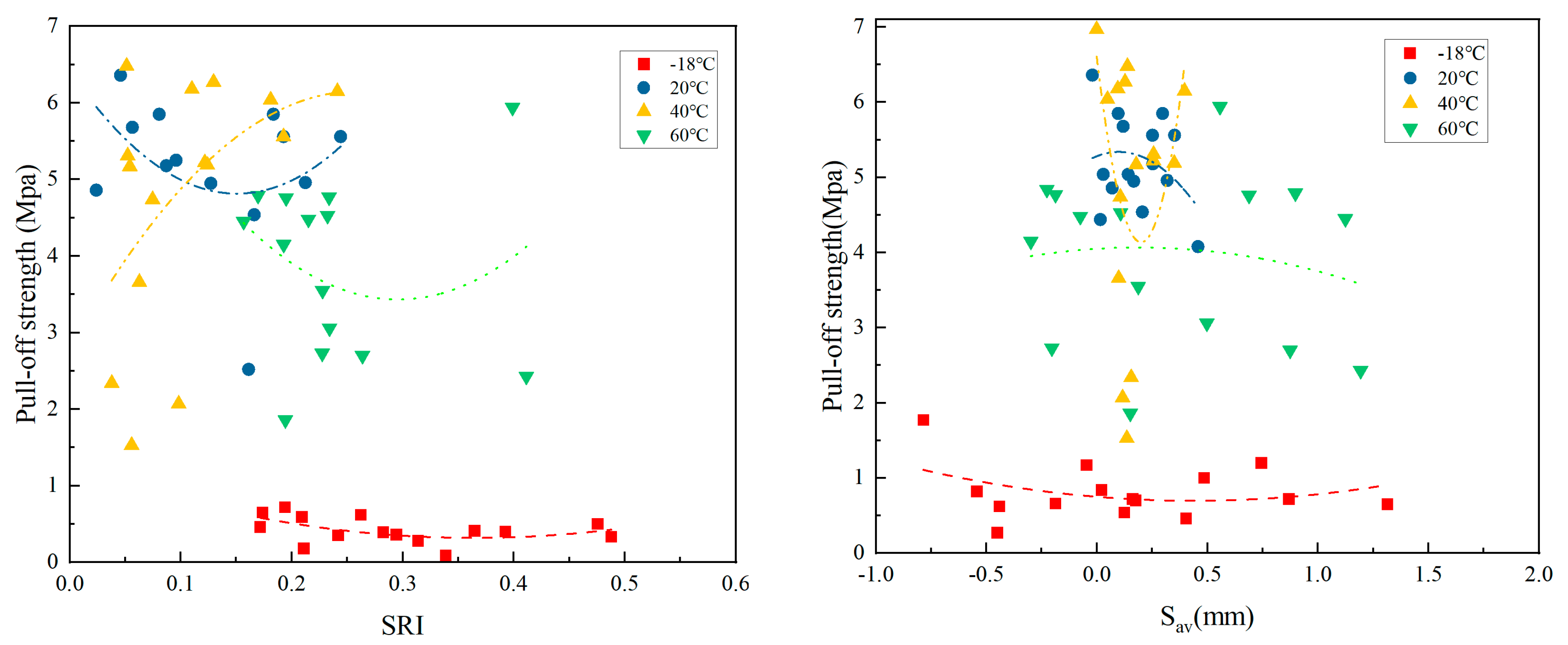

3.2.1. The Relationship Between SRI, Sav, and POS at Different Curing Temperatures

3.2.2. The Relationship Between Sa, Sq, and POS at Different Curing Temperatures

3.2.3. The Relationship Between Sz, Ssk, Sku, and POS at Different Curing Temperatures

3.2.4. The Relationship Between As, Ar, and POS at Different Curing Temperatures

3.3. Model of Texture Feature Parameters and Epoxy Pull Strength at Different Temperatures

3.3.1. Correlation Coefficient Between Three-Dimensional Parameters and Drawing Strength at Different Temperatures

3.3.2. Pull-Off Strength of Coating at −18 °C

3.3.3. Pull-Off Strength of Coating at 20 °C

3.3.4. Pull-Off Strength of Coating at 40 °C

3.3.5. Pull-Off Strength of Coating at 60 °C

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Grinding treatments significantly altered the microstructure of concrete surfaces. While grinding introduced scratches and exposed more penetration channels, enhancing the mechanical interlocking effect of the coating, the roughness index of silica fume (indicating large pore defects) did not change significantly, indicating that the surface treatments primarily affected the microstructure rather than the macrostructure. Three-dimensional modeling further confirmed that the actual effects of pore expansion and scratch increase after grinding were consistent with the negative correlation of three-dimensional morphology parameters (Sa, Sq).

- (2)

- Temperature regulation of the morphology–strength relationship: At low temperatures (−18 °C), the resin’s poor fluidity prevented it from filling the peaks and valleys on rough surfaces, leading to a more severe negative impact on Sa and the proportion of pores. It is recommended to keep Sa < 0.35 and the absolute pore ratio < 15%. At room temperature (20 °C), the resin’s fluidity improved, but high roughness (Sa > 0.45) still limited penetration. This model’s optimal Sa value of 0.375 results in a tensile strength exceeding 5.5 MPa. At medium to high temperatures (40–60 °C), the resin’s filling ability was optimized, partially compensating for rough defects. However, high temperatures accelerated curing shrinkage, and the negative effects of Sa and the pore ratio reappeared. It is necessary to balance roughness with thermal stress risks.

- (3)

- Based on the nonlinear regression analysis, a quantitative model has been established for the relationship between drawing strength and morphological parameters at different temperatures. In the 20 °C model, strength is quadratic with Sa, with the optimal Sa value being approximately 0.375; for every 10% increase in the porosity ratio, the strength decreases by 0.8 MPa. In the −18 °C model, strength increases logarithmically with Sa, but the sensitivity to pore defects is higher, so controlling the porosity ratio should be prioritized. In the 60 °C model, the combined effect of the Sa index and the square root of pore size suggests that Sa should be kept below 0.35 to avoid thermal stress concentration.

- (4)

- In actual concrete coating applications, it is recommended to optimize the surface roughness through grinding, strictly control the absolute proportion of holes, and prioritize using preheated or low-viscosity resin in a low-temperature environment to improve permeability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.; Chen, S.; Xu, Q.; Huang, Y. Modeling capillary water absorption in concrete with discrete crack network. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04017263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Kang, H.W.; Zhang, Z.W. New measurement method of concrete pavement surface macro-texture. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 382, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, K.J.; Zhou, W.F. Evaluation of surface textures and skid resistance of pervious concrete pavement. J. Cent. South Univ. 2013, 20, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Gonzalez, M.; Tighe, S.L.; Shalaby, A. Three-dimensional surface texture of Portland cement concrete pavements containing nanosilica. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2016, 19, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, Ł.; Krzywiński, K.; Michoń, M. The influence of texturing of the surface of concrete substrate on its adhesion to cement mortar overlay. J. Adhes. 2019, 96, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; He, Y.; Leng, Z.; Wang, D.; Hong, B.; Xiong, J.; Wei, J.; Oeser, M. Comparison of the polishing resistances of concrete pavement surface textures prepared with different technologies using the Aachen polishing machine. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04021231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitkus, A.; Andriejauskas, T.; Šernas, O.; Čygas, D.; Laurinavičius, A. Definition of concrete and composite precast concrete pavements texture. Transport 2019, 34, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Shalaby, A. Relating concrete pavement noise and friction to three-dimensional texture parameters. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2015, 18, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; He, G.; Dai, S.; Zhao, H.; Yu, L.; Wang, L. Hydrogel antifouling coating with highly adhesive ability via lipophilic monomer. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2022, 307, 2100812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado, F.; Toledo, L.; de la Osa, A.R.; Esteban-Arranz, A.; Sacristan, J.; Pellegrin, B.; Steck, J.; Sanchez-Silva, L. Adhesion enhancement and protection of concrete against aggressive environment using graphite-Fe2O3 modified epoxy coating. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 379, 131179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadfeau, C.; Omary, S.; Belhaj, E.; Fond, C.; Feugeas, F. Characterization of the surface of formworks—Influence of surface energy and texture on demolding forces. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 272, 121947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Q.; Lu, Z.X.; Zhao, L.Y.; Li, Z.H.; Guo, B.; Bai, X.F. The measurement of three-dimensional road roughness based on laser triangulation. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 346, 812–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Fujii, Y.; Sawada, Y.; Okumura, S. Assessment of wood surface roughness: Tactile vs. 3D Gaussian parameters. J. Wood Sci. 2004, 50, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.C.; Liu, Q.S.; Huang, J.H. New criterion for rock joints based on three-dimensional roughness parameters. J. Cent. South Univ. 2014, 21, 4653–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.T.; Jiang, Q.R.; She, C.X. Research on three-dimensional roughness characteristics of tensile granite joint. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 204–208, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yong, R.; Luo, Z.; Du, S. A novel method for determining the three-dimensional roughness of rock joints based on profile slices. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 4303–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Wu, X.X.; Sun, L.B.; Li, S.Q. New explicit correlations for critical sticking velocity of adhesive particles: Finite element study. J. Aerosol Sci. 2022, 160, 105918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri, S.; Ranjbar, Z.; Rastegar, S.; Deflorian, F. A new approach to estimates the adhesion durability of an epoxy coating through wet and dry cycles using creep-recovery modeling. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 159, 106442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Rittel, D. Three-dimensional stochastic modeling of metallic surface roughness resulting from pure waterjet peening. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2017, 120, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Li, G.D. Shrinkage of new concrete restrained by old concrete based on interface roughness. In Applied Mechanics and Materials; Trans Tech Publications, Ltd.: Wollerau, Switzerland, 2013; Volume 291–294, pp. 1168–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Tang, B. Influence of surface roughness on concrete nanoindentation. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2020, 26, 3818–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schabowicz, K.; Wójcicka-Migasiuk, D.; Urzędowski, A.; Wróblewski, K. Nondestructive investigations of expansion gap concrete roughness. Measurement 2021, 182, 109603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayinde, O.O.; Wu, E.; Zhou, G. Bond behaviour at concrete-concrete interface with quantitative roughness tooth. Adv. Concr. Constr. 2022, 13, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, T.; Li, G.; Zhang, H. Concrete surface roughness measurement method based on edge detection. Vis. Comput. 2024, 40, 1553–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Hu, Z.; Wang, B.; Li, Q.; Xu, Y. Effect of roughness and adhesive on the strength of concrete-to-concrete interfaces cast from 3D-printed prefabricated plastic formworks. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 368, 130423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altland, S.; Wadhai, V.; Nair, S.; Yang, X.; Kunz, R.; McClain, S. A distributed element roughness model for generalized surface morphologies. Comput. Fluids 2025, 298, 106651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y. A predictive model of milling surface roughness. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 108, 2755–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Yang, D.; Guo, Y. Laser ultrasonic damage detection in coating-substrate structure via Pearson correlation coefficient. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 353, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Feng, P.; Lv, Y.; Geng, Z.; Liu, Q.; Liu, X. A comparative study on UV degradation of organic coatings for concrete: Structure, adhesion, and protection performance. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 149, 105892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Wei, J.; Xu, W.; Chen, Y.; Huang, H.; Hu, J.; Yu, Q. Design, preparation, and performance of a novel organic–inorganic composite coating with high adhesion and protection for concrete. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 234, 109695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshami, A.A.; Bonnet, S.; Khelidj, A.; Sail, L. Novel anticorrosive zinc phosphate coating for corrosion prevention of reinforced concrete. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2016, 21, 572–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sequence Number | Surface 1 Initial SRI | Surface 1 Grind SRI | Surface 2 Initial SRI | Surface 2 Grind SRI | Surface 3 Initial SRI | Surface 3 Grind SRI | Surface 4 Initial SRI | Surface 4 Grind SRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.4610 | 0.4870 | 0.1908 | 0.2091 | 0.0804 | 0.0378 | 0.2557 | 0.2340 |

| 2 | 0.1012 | 0.0806 | 0.3534 | 0.3389 | 0.2163 | 0.0522 | 0.2610 | 0.2275 |

| 3 | 0.0567 | 0.0871 | 0.4666 | 0.4879 | 0.1531 | 0.1216 | 0.3697 | 0.2336 |

| 4 | 0.1101 | 0.1223 | 0.3818 | 0.3649 | 0.0994 | 0.1240 | 0.1421 | 0.2151 |

| 5 | 0.4127 | 0.3620 | 0.2536 | 0.2622 | 0.2964 | 0.2412 | 0.2095 | 0.1697 |

| 6 | 0.0667 | 0.0458 | 0.2434 | 0.2110 | 0.0506 | 0.0746 | 0.2604 | 0.2637 |

| 7 | 0.0602 | 0.0239 | 0.3258 | 0.3139 | 0.0404 | 0.0558 | 0.2430 | 0.1943 |

| 8 | 0.1295 | 0.0564 | 0.3057 | 0.2943 | 0.0466 | 0.0542 | 0.2091 | 0.2770 |

| 9 | 0.2865 | 0.2440 | 0.2660 | 0.2419 | 0.1389 | 0.1296 | 0.1208 | 0.1927 |

| 10 | 0.3918 | 0.1926 | 0.1971 | 0.1716 | 0.1593 | 0.1101 | 0.1816 | 0.195 |

| 11 | 0.1756 | 0.1612 | 0.3620 | 0.3925 | 0.0817 | 0.0627 | 0.3512 | 0.4114 |

| 12 | 0.2175 | 0.1835 | 0.2497 | 0.2825 | 0.0737 | 0.0981 | 0.3962 | 0.3989 |

| 13 | 0.1309 | 0.1271 | 0.2435 | 0.2756 | 0.1334 | 0.0513 | 0.1975 | 0.2322 |

| 14 | 0.2269 | 0.0958 | 0.2682 | 0.1940 | 0.1385 | 0.1810 | 0.2314 | 0.2277 |

| 15 | 0.1745 | 0.1662 | 0.1962 | 0.1737 | 0.1534 | 0.1544 | 0.1834 | 0.1566 |

| Parameter | Correlation Coefficient (p-Value), n = 15 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −18 °C | 20 °C | 40 °C | 60 °C | |

| Sa | −0.113 (0.772) | −0.678 (0.044) | −0.690 (0.040) | 0.195 (0.614) |

| Sq | −0.118 (0.764) | −0.194 (0.618) | −0.516 (0.153) | 0.353 (0.356) |

| Ssk | 0.414 (0.267) | 0.489 (0.183) | −0.247 (0.520) | −0.281 (0.468) |

| Sku | 0.585 (0.098) | 0.458 (0.215) | −0.124 (0.750) | 0.006 (0.987) |

| Sz | 0.060 (0.867) | −0.103 (0.792) | −0.412 (0.270) | 0.325 (0.392) |

| Aa | −0.028 (0.943) | −0.795 (0.011) | −0.412 (0.270) | 0.158 (0.678) |

| Ar | −0.361 (0.339) | −0.564 (0.115) | −0.818 (0.007) | 0.199 (0.607) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, T.; Xu, P.; Chen, H.; Yuan, T.; Xu, A.; Chen, C.; Wu, Y. Analysis of Surface Texture Distribution Characteristics of Concrete Substrate and Modeling of Coating Adhesion Strength. Materials 2025, 18, 5412. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235412

Fan T, Xu P, Chen H, Yuan T, Xu A, Chen C, Wu Y. Analysis of Surface Texture Distribution Characteristics of Concrete Substrate and Modeling of Coating Adhesion Strength. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5412. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235412

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Tao, Peng Xu, Huaxin Chen, Teng Yuan, Anhua Xu, Cheng Chen, and Yongchang Wu. 2025. "Analysis of Surface Texture Distribution Characteristics of Concrete Substrate and Modeling of Coating Adhesion Strength" Materials 18, no. 23: 5412. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235412

APA StyleFan, T., Xu, P., Chen, H., Yuan, T., Xu, A., Chen, C., & Wu, Y. (2025). Analysis of Surface Texture Distribution Characteristics of Concrete Substrate and Modeling of Coating Adhesion Strength. Materials, 18(23), 5412. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235412