1. Introduction

The global energy landscape is undergoing a rapid transition towards decarbonisation, with solar photovoltaic (PV) power emerging as a pivotal renewable energy technology, as evidenced by the continuously rapid growth in installed capacity [

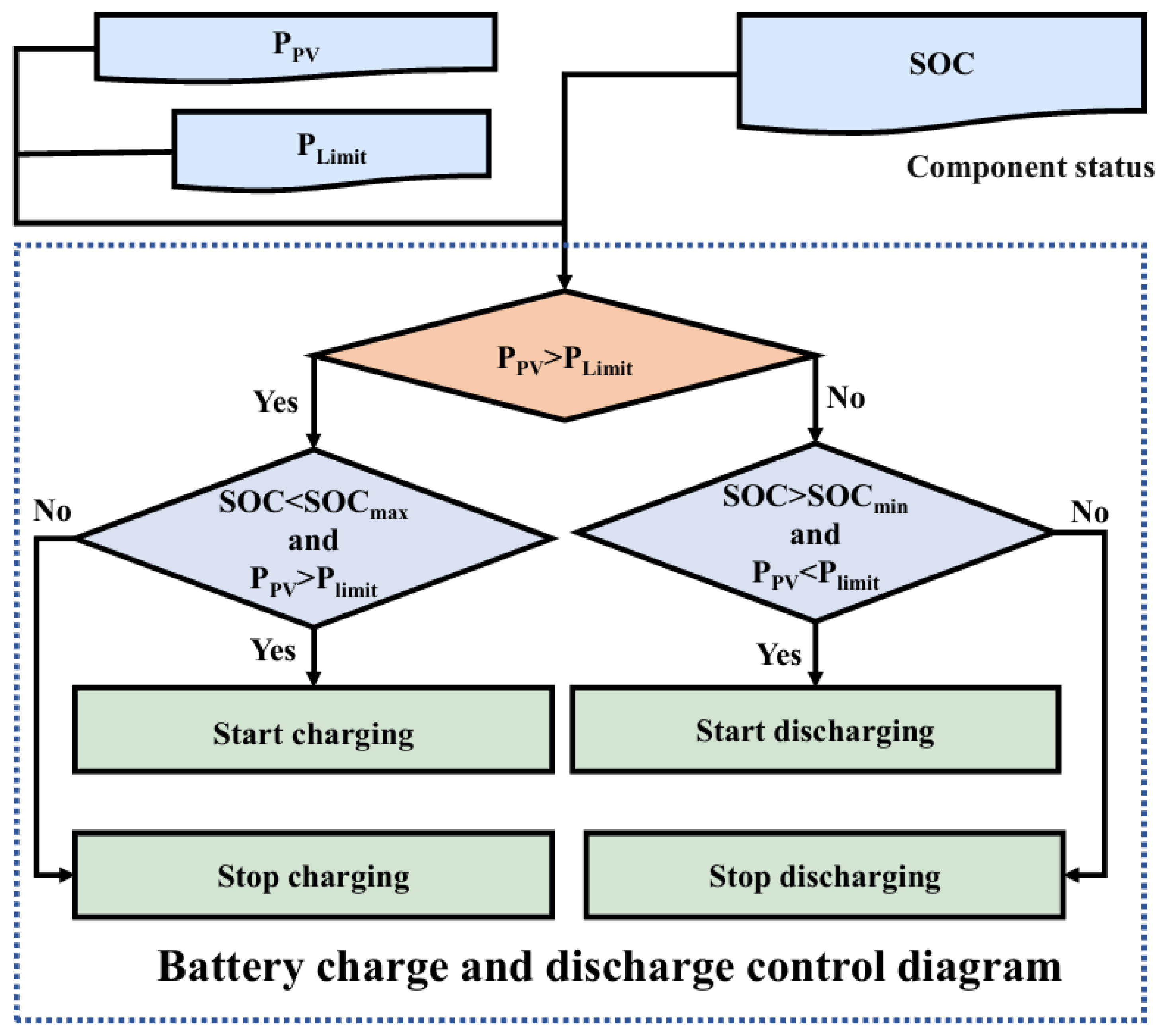

1]. However, in regions with high photovoltaic (PV) penetration, the inherent intermittency, volatility, and forecasting uncertainties of solar power create a fundamental mismatch with grid flexibility as deployment scales up. This phenomenon is especially pronounced in regions where the capacity to reduce peak demand and the transmission capabilities are inadequate to manage the variable nature of PV generation. In response to this issue, a significant number of system operators have implemented limitations on the grid injection power of photovoltaic (PV) systems, resulting in substantial solar curtailment. This phenomenon results in substantial energy wastage and economic losses, thereby hindering the sustainable development of the PV industry [

2,

3,

4,

5].

In order to address the issue of solar curtailment, the deployment of energy storage systems is recognised as a viable technical solution. A substantial body of research is currently focused on the utilisation of energy storage for the purpose of facilitating spatiotemporal energy transfer. This is intended to enhance the grid’s capacity to accommodate photovoltaic (PV) generation.

Some researchers have pursued performance improvements through optimizing multi-energy and storage coordination. Liu et al. [

6] developed a term coordinated scheduling model for the wind-solar-hydro hybrid pumped storage (WSHPS) system with peak shaving operation. The results showed that compared with the wind-solar-hydro hybrid (WSH) system, the total power generation of the WSHPS system in the dry, normal, and wet year increased by 10.69%, 11.40%, and 11.27%, respectively. The solar curtailment decreased by 68.97%, 61.61%, and 48.43%, respectively. Du et al. [

7] developed proposed methodology for the purpose of enhancing the efficiency of a photovoltaic-battery-hydrogen coupled system (PBHS), with particular consideration given to the temporal variation in electricity tariffs. A non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm based on elite strategy (NSGA-II) was introduced as an effective tool for solving mathematical models, the proposed plan achieved a significant reduction of 7.7% in annual investment costs and a 15.16% reduction in annual carbon emissions. Bazdar et al. [

8] investigated the synergistic co-optimisation of economy and resilience for distributed hybrid energy systems (HES) that integrate limited renewable energy sources with hybrid energy storage. The focus was specifically on the combination of adiabatic compressed air energy storage (A-CAES) and batteries. The proposal of a two-stage sizing-dispatch model was intended to facilitate the determination of the optimal configuration. The findings indicated that by optimizing sizing and integrating storage, a substantial annual enhancement in resilience, amounting to approximately 41.1%, can be accomplished. Jiang et al. [

9] proposed a wind farm energy storage capacity optimisation model with the objective of maximising wind energy utilisation while reducing storage infrastructure costs. Particle swarm optimisation results demonstrated that this model can smooth wind energy output at lower cost and with greater utilisation efficiency.

Others have advanced system sizing and configuration methodologies. Ibrahim et al. [

10] presented a modified sizing algorithm based on the Golden Section Search method and the objective was to enhance the efficiency of the energy storage unit by optimizing the number of batteries. Ruan et al. [

11] proposed an optimal configuration model for hybrid energy storage systems in scenarios with high renewable energy penetration. The model considered multiple constraints, including power flow, unit commitment, and storage operation. Based on these constraints, it determined the optimal configuration of storage systems. Makhubele et al. [

12] proposed a hybrid energy system. The system included rooftop PV installations, lithium-ion storage, and connection to the national grid. A techno-economic analysis was conducted over a 25-year project lifespan to evaluate energy cost, payback period, net present cost, and carbon dioxide emissions. The results showed that the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) was USD 0.0071/kWh. Liu et al. [

13] proposed a novel energy management strategy that accounts for battery cycle ageing, grid mitigation, and local time-of-use pricing. Single-criterion optimisation has been demonstrated to exhibit superior performance in comparison to existing scenarios for the target building across a range of metrics, including energy supply, battery storage, grid, and system-wide considerations. Multi-criterion optimisation considering all performance indicators reveals that photovoltaic self-consumption and efficiency can be enhanced by 15.0% and 48.6%, respectively. Sleptchenko et al. [

14] presented a generalized optimization model for cost minimization in combined energy production and storage facilities. The model can incorporate any combination of dynamic supply, storage, and energy-intensive product demand.

Furthermore, several contributions focused on grid integration. Chen et al. [

15] proposed a distributed energy storage (DES) optimization allocation strategy based on transmission betweenness and source-network-load synergy in active distribution networks. And an optimal siting calculation method for energy storage based on the node transmission betweenness was proposed. The results showed that the system’s renewable energy consumption rate reached 98.29%. Additionally, Li et al. [

16] proposed an optimization strategy for energy storage, and aimed to improve system performance within current group control system. A bilevel coordinated planning model for distributed energy storage (DESS)was developed. The result showed that the proposed strategy significantly enhanced the network’s ability to absorb photovoltaic energy. Li et al. [

17] investigated the coordination and optimisation of multi-site distributed battery energy storage systems participating in grid demand response. Furthermore, it proposed a strategic analysis framework for multi-site distributed battery energy storage systems engaging in demand response.

However, extant research predominantly employs conditional optimisation analysis, aiming to identify a single optimal solution for a specific set of conditions. While this approach is indeed effective, it fails to reveal the dynamic evolution of economic benefits during the expansion of energy storage capacity. In the event of external parameter alteration, solutions founded upon obsolescent conditions may become invalid. The present study employs a marginal analysis framework to address these limitations. The examination of the evolution of marginal benefits (MCF, MCL, MRR) provides a comprehensive economic analysis of capacity allocation. This approach identifies critical points of benefit maximisation and provides a dynamic basis for risk assessment.

The article’s organisation is as follows:

Section 1 (introduction) outlines the current research progress, limitations, knowledge gaps, objectives, and rationale;

Section 2 discusses systems modelling and research methods;

Section 3 presents the results and analysis;

Section 4 discusses the major findings and future work; and

Section 5 summarises the key findings of the study.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Analysis of Baseline Scenario Results

Power Curtailment Scenarios for Non-Energy Storage Power Plants Only

Figure 2 shows the relationship between daily solar irradiance per square metre and power generation. As shown in

Figure 2a, the graph shows that the two variables generally correlate linearly. In

Figure 2b, the output power of the photovoltaic array and the actual electricity generation follow the same monthly variation trend. Below is a correlation analysis of the output power of the photovoltaic array and the actual grid-connected power. The linear correlation between the two variables is measured using the Pearson correlation coefficient (

rxy).

This paper denotes the monthly photovoltaic array output as

Exi and the monthly grid-connected electricity as

Eyi, as described in Equation (12).

In the formula, represents the average monthly output of the photovoltaic array, represents the average grid-connected electricity generation across all months, where n = 12.

As shown in

Table 3, the Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.999827 under the scenario of power plants with no energy storage and limited electricity generation only. This indicates an extremely strong positive correlation between the photovoltaic array’s electricity output and electricity generation, proving that there is no significant distortion in the data throughout the entire process, from power generation to grid connection. This validates the rationality of the established system. Additionally, under these operating conditions, the three-performance metrics are as follows:

CF is 0.184814372,

CL is 3,388,529, and

CLR is 0.173090349.

3.2. Annual Electricity Generation Analysis

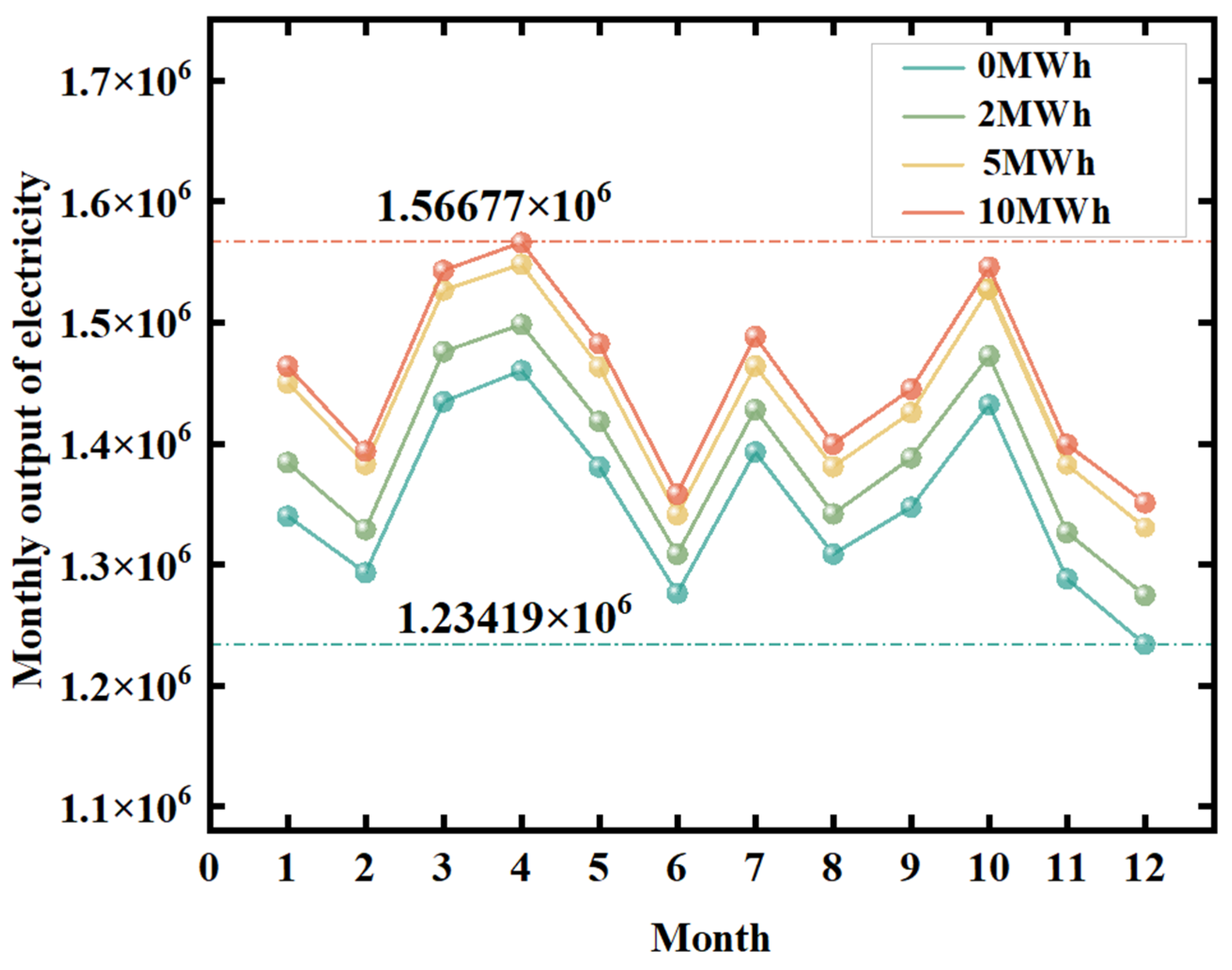

In order to compare the impact of energy storage battery capacity on curtailment issues directly, this section selects S2 as the small-capacity battery, S5 as the medium-capacity battery and S10 as the large-capacity battery. The energy storage batteries are configured on small, medium and large scales in order to compare the system’s monthly electricity output.

As shown in

Figure 3, where 0 MWh represents the monthly output of electricity of the system without energy storage participation, the monthly electricity output shows a significant increase as the energy storage capacity increases from 0 MWh to 2 MWh. Furthermore, the annual total generation demonstrates a consistent upward trend as the energy storage capacity is incrementally raised from the base level to 5 MWh and further to 10 MWh.

Photovoltaic power stations equipped with energy storage systems can store excess solar power that was previously curtailed in energy storage batteries. As storage capacity increases, the absorption rate of the system improves further. The energy stored in these systems can be released during periods of low irradiation, effectively generating power. In essence, the storage system shifts curtailed midday power to the evening when solar output is low, thereby overcoming grid curtailment constraints.

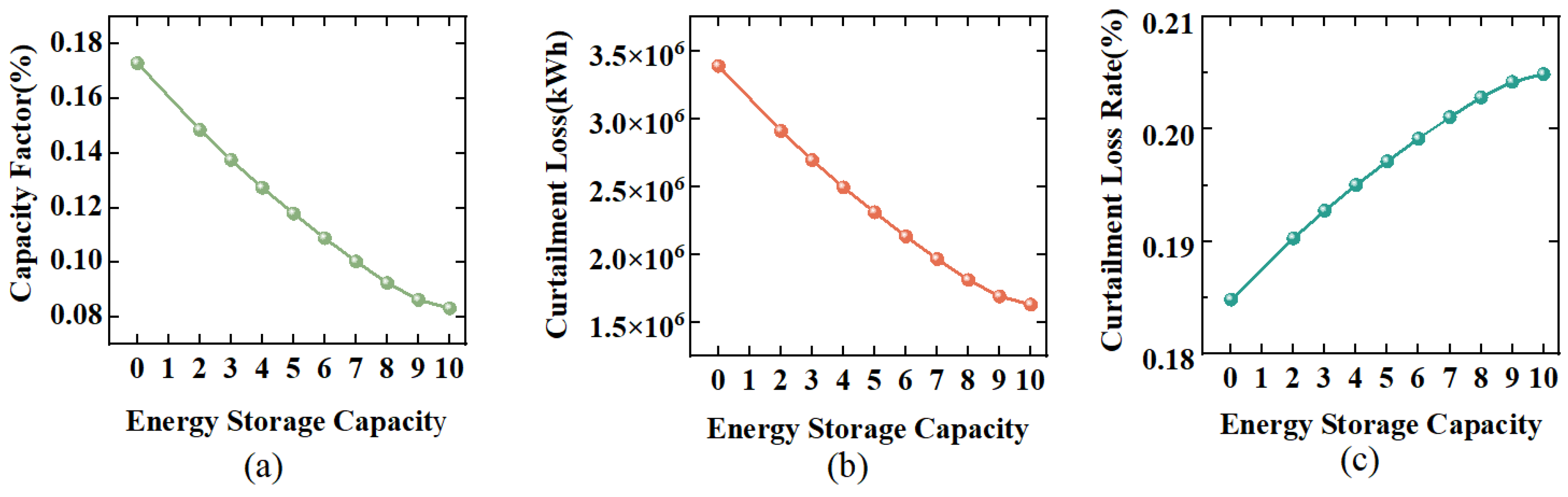

3.3. CF, CL, CLR Analysis

Energy storage capacity is a key parameter that influences CF, CL and CLR. As illustrated in

Figure 4a, the energy storage configuration increases from 0 MWh to 10 MWh, the system capacity factor rises steadily from 0.1848 to 0.2050. A small energy storage capacity in the system can restrict the number of charge-discharge cycles that the storage units can perform, resulting in a low capacity factor. However, when capacity increases, the storage units can respond more flexibly to grid demands, extending the regulation duration and enabling them to cover morning and evening load peaks and troughs. This confirms the value of flexible regulation of storage units for photovoltaic power plants, further improving the utilisation rate of photovoltaic equipment over time.

Figure 4b demonstrates the impact of energy storage on curtailed solar power. When the storage capacity is 0 MWh, the annual curtailed power is 3,388,529 kWh. Increasing the storage capacity to 2 MWh reduces the annual curtailed power output sharply to 2,910,126 kWh, and scaling it up to 10 MWh lowers it further to 1,628,894 kWh. This demonstrates that energy storage can directly absorb excess power from curtailed PV generation. This enables the system to transition from ‘immediate PV absorption’ to a more flexible operational mode, which significantly enhances the flexibility of the power generation system.

Figure 4c shows that as the energy storage capacity increases from 0 MWh to 10 MWh, the curtailment loss rate decreases from 0.1731 to 0.0832, which corresponds to the direct absorption effect of energy storage on curtailed electricity shown in

Figure 4b. This indicates that deploying energy storage systems to accommodate more renewable energy directly reduces the output share of conventional power units. As their output decreases, the ‘relative proportion’ of curtailment also declines.

Together, these three factors demonstrate how energy storage capacity improves the regulatory capabilities of photovoltaic power generation systems in the event of curtailment. Improving storage utilisation efficiency directly reduces curtailed electricity and indirectly optimises the entire power generation system, making it a key driver for increasing PV integration.

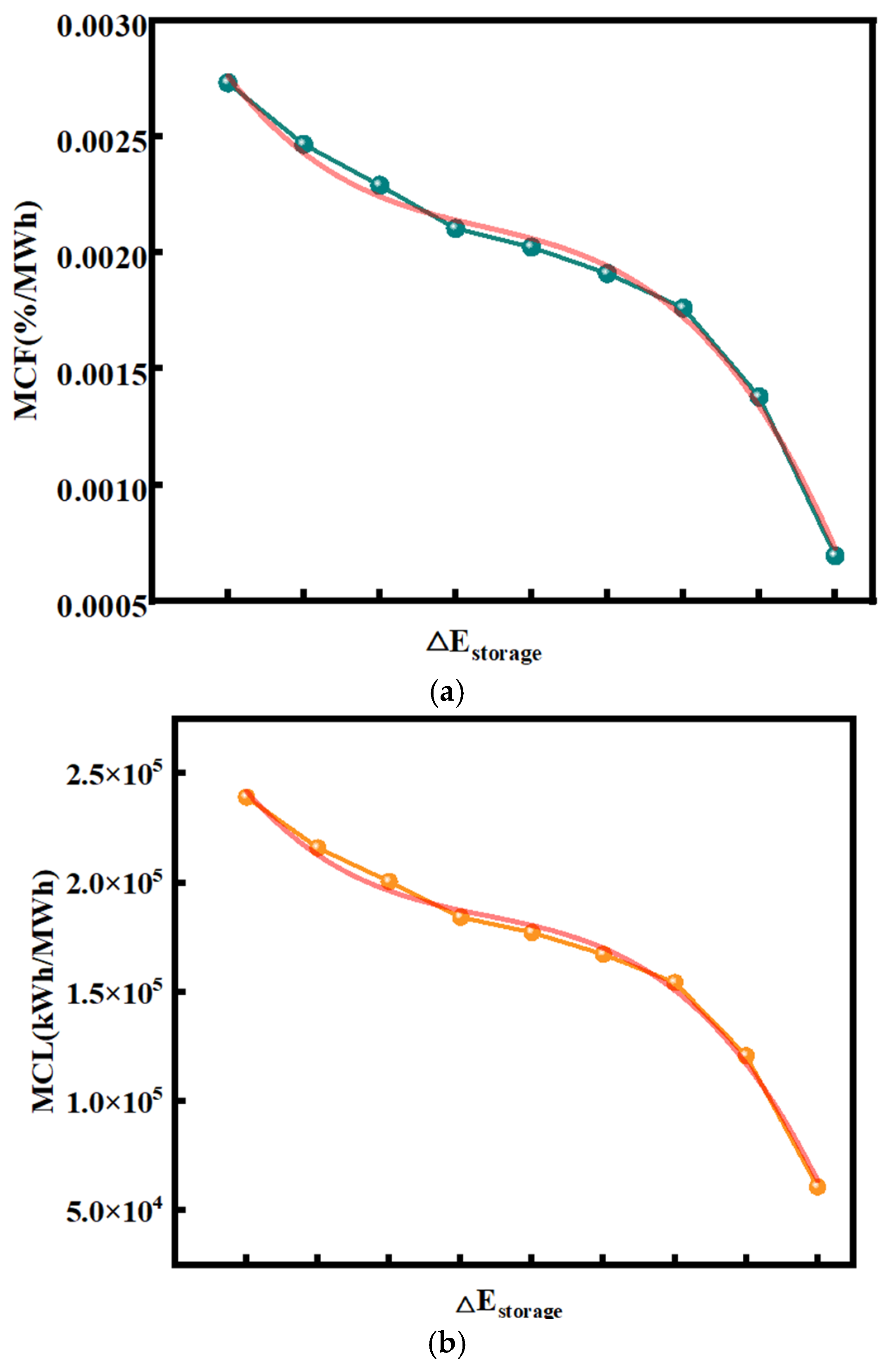

3.4. Marginal Benefit Analysis

As demonstrated in

Figure 5a,b, both MCF and MCL demonstrate a downward trend with each unit increase in energy storage capacity. It is evident that when the storage capacity is increased from 8 MWh to 9 MWh, there is a marked decline in both MCF and MCL. This finding suggests that the enhancement in system capacity factor, attributable to each unit of additional storage capacity, exhibits a progressive decline. The amount of curtailed solar power that can be captured and utilised per unit of new capacity diminishes progressively, exhibiting diminishing marginal returns. This suggests that as energy storage capacity continues to expand, the performance gains per unit of new capacity and the reduction in curtailed solar generation may be associated with saturated equipment utilisation and system regulation capabilities, as well as the fragmented absorption of curtailed solar power by newly added storage capacity.

As shown in

Figure 5c, the MRR demonstrates a declining trend with each unit increase in energy storage capacity. Especially, when storage capacity increases from 8 MWh to 9 MWh, the MRR experiences a precipitous decline. It is evident that an augmentation in capacity, in excess of 9 MWh, results in the MRR approaching zero. This indicates a critical point for the MRR with respect to unit energy storage capacity increases.

This critical point indicates an economic capacity ceiling for energy storage expansion. Beyond this threshold, the revenue mechanism becomes ineffective, and the sharp decline in MRR may stem from an imbalance between incremental revenue and incremental investment costs. The declining returns of MCF and MCL indicate that the available capacity has almost reached its limit in terms of absorbing reduced solar power, resulting in negligible additional benefits and the unit cost of energy storage continues to present a challenge in terms of reduction in the short term, consequently giving rise to persistently high incremental investment costs. The preceding analysis demonstrates that the MRR threshold delineates the economic boundary for energy storage capacity planning. Beyond this threshold, the economic viability is significantly diminished.

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

To assess the impact of key parameter uncertainties on the economic viability of energy storage systems, this section conducts single-factor sensitivity analyses for five core parameters. The basic settings for these five parameters are shown in

Table 4. Power Curtailment (PC) is the grid-connected power limitation during photovoltaic power generation grid connection. Unit Energy Storage Cost (UESC) refers to the incremental investment cost resulting from increased unit energy storage capacity. Curtailment Reduction (CR) is a key performance indicator used to quantify how energy storage systems enhance the grid integration capacity of PV power. It specifically refers to the reduction in annual curtailment loss between two scenarios with different energy storage configurations. Unit Electricity Price (UEP) is the price of electricity per kWh, and Inverter Efficiency (IE) is the ratio of input DC power converted to AC power by the inverter. These five parameters were selected as sensitivity factors. Each parameter varied by 20% from its baseline value to study the corresponding changes in Marginal Return Rate (MRR). This analysis aims to identify key drivers affecting the economic viability of energy storage investments and provide direction for system optimization.

As shown in

Figure 6, varying different parameters have different effects on MRR. The impact of PC on MRR is found to be significant, while the effect of IE on MRR is found to be negligible. Conversely, UESC, CL, and UEP have been shown to exert considerable influence on MRR.

It is evident that among these, PC has the most extensive coverage area, thereby signifying that its fluctuations exert the most substantial impact on MRR. The theoretical upper limit of system revenue is defined by PC. In regions where photovoltaic (PV) penetration is high, curtailment is identified as the primary source of losses. When the PC threshold is relaxed from 6 MW to 6.5 MW, a significant amount of high-value curtailed energy is immediately released. This energy can be converted into revenue at a negligible marginal cost, thereby significantly boosting MRR. Conversely, the imposition of further PC restrictions would precipitate a precipitous decline in MRR. The CR and UEP models demonstrate considerable overlap, exhibiting consistent impacts on MRR. For UESC and UEP, both factors directly determine project economic viability. It is evident that an increase in electricity prices will result in a linear rise in the value of all generated electricity. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that this will enhance incremental revenue from curtailment mitigation via energy storage. It is evident that since storage investment constitutes the most substantial incremental cost of the system, fluctuations in its cost directly impact the rate of return, thereby exerting a considerable influence on MRR. With regard to IE, its comparatively negligible impact on MRR change may be attributed to the restricted revenue variation it engenders. In comparison with substantial incremental investments, such as energy storage, its marginal contribution ratio remains negligible.

Based on the above analysis, it is imperative to prioritise the enhancement of PC through technological or policy measures. Subsequent to this, there is a necessity to pursue higher UEP and to select energy storage systems that are more cost-effective.

4. Discussion and Future Work

4.1. Limitations

Although this study effectively revealed the marginal benefit patterns of capacity configuration for photovoltaic-storage systems using the PVsyst simulation framework, certain limitations must be acknowledged. Firstly, the meteorological databases integrated into the PVsyst software (such as Meteonorm) have inherent time lags and may therefore fail to reflect the latest local climate change trends accurately. This may affect the accuracy of long-term performance predictions. Secondly, as PVsyst is a system-level simulation tool focused on energy balance, it employs simplified models for components such as batteries, which fail to precisely simulate their internal dynamic characteristics.

4.2. Policy and Practical Implications

Research findings indicate that moderately relaxing power curtailment thresholds is a more cost-effective way of enhancing PV integration capacity than solely deploying large-capacity energy storage systems. Grid companies are therefore recommended to prioritise enhancing regional grid flexibility and transmission capacity.

4.3. Adaptability to Larger and Hybrid Energy Systems

This study employs an optimisation framework based on marginal benefits, extending beyond the specific case of individual photovoltaic-storage power stations. The core principles of the system demonstrate high adaptability and can be effectively scaled to larger and hybrid energy systems for the purpose of evaluating the value of energy storage.

4.3.1. Applied to a Larger Grid

When the system is expanded to encompass regional or national grids, the system boundary is extended from single-point interactions to the entire grid. Consequently, key parameters require corresponding adjustments.

Power curtailment limits will no longer represent constraints at individual substations, but will instead reflect transmission capacity bottlenecks along critical corridors or the grid’s overall capacity to accommodate variable renewable energy sources.

The Curtailment Loss would be quantified as the total wasted renewable energy across the entire grid region, often referred to as system-wide curtailment.

At this scale, the framework’s ability to identify the marginal value of storage becomes crucial for grid planning. It can answer questions such as whether it is more cost-effective to invest in a large-scale, centralized storage facility to relieve a transmission constraint or to deploy distributed storage at multiple grid congestion points.

4.3.2. Applied to Hybrid Energy Systems

The framework can be extended to model hybrid systems comprising wind, solar, batteries, and even hydrogen storage.

When adapting to hybrid systems, new component models, such as wind power output data and hydrogen storage, must be incorporated. The objective shifts from minimising curtailed generation to either minimising the system-wide cost or maximising renewable energy utilisation.

4.4. Future Work

Despite the utilisation of multi-scenario simulations and sensitivity analyses in this paper, which serve to mitigate certain uncertainties, it should be noted that the meteorological data within PVsyst is not updated in real time. Future research utilise higher-precision measured data in order to enhance the model’s accuracy and generalisation capability.

The present study principally focuses on technical and economic considerations; future work may incorporate environmental benefits to achieve multi-objective optimisation.

The transition from deterministic to probabilistic analysis is a significant development in the field. For instance, employing Monte Carlo simulations and defining key parameters as probability distributions is able to generate a range of potential outcomes for metrics such as net present value. This would directly quantify investment risk.