Environmental Auditing, Public Finance, and Risk: Evidence from Moldova and Bulgaria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Objectives

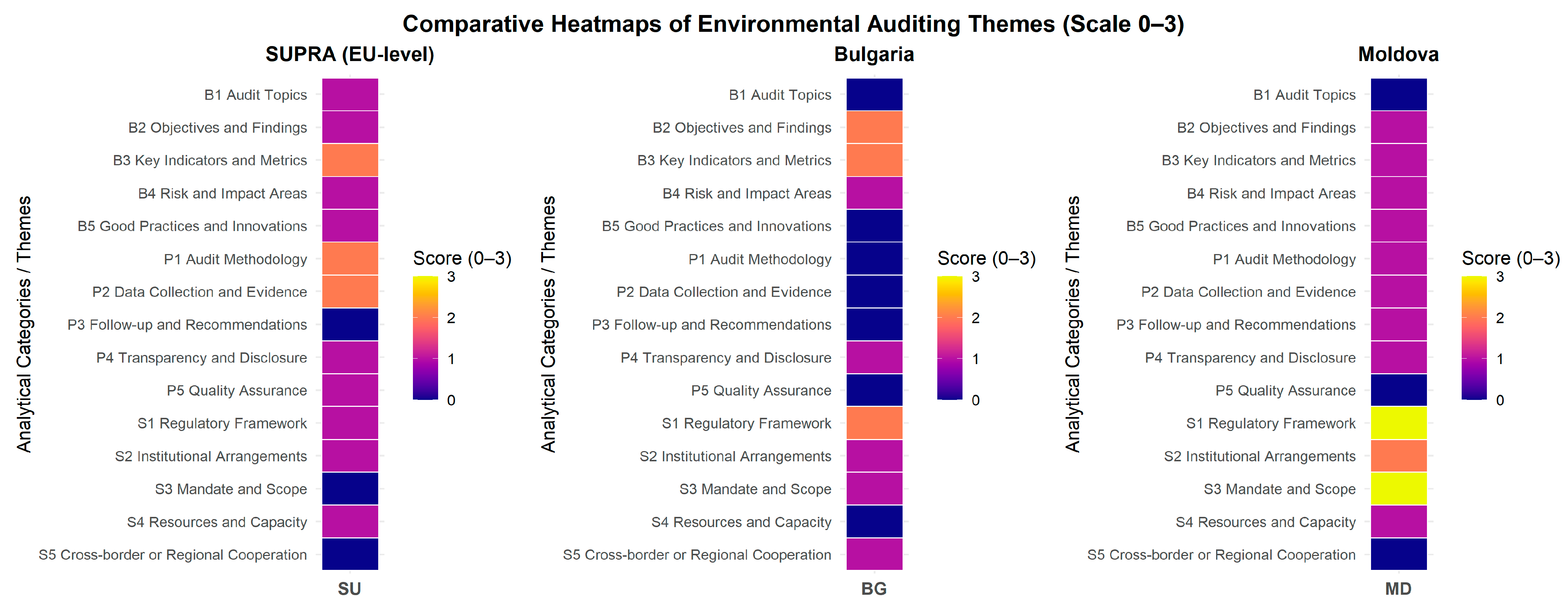

- Structural Dimension: This dimension focuses on the foundational elements of the audit system, including the legal and institutional framework (e.g., laws, mandates, institutional setup) and the digital foundations (e.g., data availability, IT systems used for auditing).

- Substantive Dimension: This dimension captures the core content and focus of the audits, categorizing priority themes (e.g., climate change, water pollution, biodiversity) and the outcomes that the audits aimed to achieve (e.g., compliance, performance improvement, policy change).

- Procedural Dimension: This dimension analyzes the processes and methodologies employed, including the methods of audit execution, the types of evidence gathered and utilized, demands for transparency, and mechanisms for follow-up and implementation of audit recommendations.

- RQ1 investigates the corporate and public governance structures that enable and mandate environmental auditing: What are the structural features of the regulatory and institutional frameworks for environmental auditing in the two countries?

- RQ2 explores the sustainability themes and outcomes that form the substantive focus of audit practices: What substantive themes and audit topics dominate reported practice?

- RQ3 examines the environmental auditing procedures themselves, including methods and mechanisms for ensuring accountability: What procedural mechanisms (methods, follow-up, transparency) are used, and how do they differ across contexts?

3.2. Scope and Data Sources

- National legal databases;

- Ministerial and agency portals (environment, finance, energy);

- Websites of the Supreme Audit Institutions; and

- Professional or academic publications.

3.3. Coding Framework and Analytical Dimensions

- Structural Dimension—encompassing legal frameworks, institutional mandates, and digital infrastructures supporting environmental auditing;

- Substantive Dimension—capturing audit objectives, topics, and findings related to sustainability outcomes;

- Procedural Dimension—addressing audit methods, data collection, transparency, follow-up mechanisms, and reporting practices.

3.4. Reliability and Validity

3.5. Analytical Procedure

3.6. Ethical Considerations and Limitations

3.7. Contribution of the Methodological Approach

4. Environmental Auditing and Corporate Governance: A Comparative Analysis of Moldova and Bulgaria in Strengthening Sustainability

4.1. Results (SUPRA Level): European Framework for Environmental Auditing and Assurance

4.2. Results (Moldova Level): National Architecture of Environmental Auditing and Assurance

4.3. Results (Bulgaria Level): National Architecture of Environmental Auditing and Assurance

4.4. Cross-Country Synthesis (BG vs. MD)

5. Discussion: Audit-Driven Governance in Bulgaria and Moldova

5.1. Audit-Driven Governance Pathways: Bulgaria, Moldova, and Cross-Cutting Implications

5.2. Policy Recommendations

5.2.1. Bulgaria: Targeted Actions for “Compliance-Plus” Policy Steering

- Institutionalise follow-up tracking. Establish a public, regularly updated dashboard that lists every audit recommendation with the responsible institution, a clear deadline, current implementation status, and an explicit link to the relevant budget programme or project so that citizens and decision-makers can track delivery end-to-end.

- Deepen risk-based oversight. Align annual inspection plans with national climate- and water-risk maps and prioritise facilities using combined criteria—such as reported emissions, incident history, citizen complaints, and past non-compliance—so that supervisory resources are concentrated where environmental and health risks are greatest.

- Tighten data pipelines. Interlink electronic permitting systems, the national Pollutant Release and Transfer Register, and water/waste registries with enterprise data from the Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) and the International Organization for Standardization environmental management standard (International Organization for Standardization, 2015), and require machine-readable exports to enable analysis, comparison, and reuse across agencies.

- Address hard-to-assure areas. Develop sector-specific protocols for value-chain (Scope 3) emissions, circular-economy performance, and biodiversity impacts, and pilot external “reasonable assurance” engagements on a small set of priority indicators to build methods, confidence, and replicable practice.

- Close coordination gaps. Create an interministerial “Audit-to-Policy” forum—bringing together the Ministry of Environment, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Regional Development, and the Supreme Audit Institution—that meets annually to convert audit findings into updated programmes, targeted investment choices, and concrete milestones aligned with European Union and cohesion-funding requirements.

5.2.2. Moldova: From Diagnostic Audits to Standardised Assurance

- Codify the audit cycle. Establish in secondary legislation a minimum, repeatable sequence—planning, audit execution, issuance of recommendations, and formal follow-up—and require a single, consolidated annual implementation report that lists each recommendation, its responsible authority, milestones, and completion status to ensure continuity and accountability.

- Upgrade digital auditability. Accelerate the development of the national Pollutant Release and Transfer Register and integrate electronic permitting systems, inspection protocols, and citizen alerts submitted via the EcoAlert application into one unified, regularly updated risk index that prioritises inspections and enforcement where potential impacts and non-compliance risks are highest.

- Build capacity where it counts. Direct technical assistance toward (i) instruments of the waste economy such as extended producer responsibility and the roll-out of regional landfills and sorting facilities, (ii) continuous and quality-controlled surface and groundwater monitoring, and (iii) standardised sampling procedures and laboratory quality assurance/quality control so that audit evidence is robust and defensible.

- Leverage international transparency. Use the first Biennial Transparency Report under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change as a template for methods, verification steps, and public disclosure in adjacent themes such as waste management and air quality, and embed relevant guidance from the International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions into the Court of Accounts’ performance-audit methodology.

- Move from pilots to scale through financing. Link priority audit recommendations to concrete project pipelines supported by initiatives such as EU4Environment and international financial institutions, and define a small set of “audit indicators” that function as disbursement or phase-gate conditions so that funding is explicitly tied to the closure of audit findings.

5.2.3. Cross-Cutting: Turning Audit Evidence into Outcomes

- Ensure continuity of the audit cycle. Establish multi-year audit programmes with scheduled re-checks every 12–18 months for the most critical recommendations, assign a single responsible authority for each item, and publish timelines and completion statuses so that follow-up is predictable and accountable.

- Make data usable across systems. Require machine-readable, open formats and common identifiers for facilities and permits, and expose open application programming interfaces that interlink electronic permitting, the Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (PRTR), water and waste registries, and enterprise environmental management data from the Eco-Management and Audit Scheme and ISO 14001, so that indicators are comparable and evidence is verifiable.

- Engage stakeholders in follow-up. Standardise public releases to include a plain-language executive summary and a technical annex, define participation windows for comments, and invite non-governmental organisations and academic experts to periodic review sessions focused on the status of implementing audit recommendations.

- Link recommendations to budgets. Map every major audit recommendation to an explicit budget line at the level of programme, measure, or project, and use results-based conditions in domestic and external financing so that funds are disbursed when implementation milestones are met.

- Share what works and scale it. Organise Bulgaria–Moldova peer-learning sprints on themes such as risk-based inspections, roll-out of the Eco-Management and Audit Scheme, and operation of the Pollutant Release and Transfer Register, and produce short, replicable “how-to” protocols with responsible owners and timelines that are published on ministry portals and revisited annually.

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Code | Name | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural | S1 | Regulatory Framework | Covers all binding or semi-binding regulatory instruments—laws, directives, regulations, and policy decisions—that establish the mandate, scope, and institutional responsibilities of environmental auditing and reporting. It reflects the structural governance layer underpinning sustainability assurance systems. |

| S2 | Institutional Arrangements | Covers organizational arrangements and governance mechanisms that define roles, mandates, and cooperation models between institutions responsible for environmental auditing, sustainability assurance, and reporting supervision. | |

| S3 | Mandate and Scope | Covers provisions that establish the authority, scope, and subject matter of environmental audits, including who conducts them, what domains are examined, and the degree of autonomy granted to auditors or assurance providers. | |

| S4 | Resources and Capacity | Refers to the availability and quality of institutional resources—financial, human, and technological—required to conduct and sustain environmental auditing, monitoring, and assurance activities. | |

| S5 | Cross-border or Regional Cooperation | Refers to institutionalized cooperation, partnerships, and joint audit initiatives across borders or within regional frameworks. | |

| Substantive | B1 | Audit Topics | Focuses on the environmental themes and issues addressed by audit institutions or sustainability assurance bodies. |

| B2 | Objectives and Findings | Refers to the purpose, evaluation criteria, and key results or conclusions of environmental audit activities. | |

| B3 | Key Indicators and Metrics | Focuses on the metrics, indicators, and data tools applied to monitor environmental or sustainability outcomes within audit processes. | |

| B4 | Risk and Impact Areas | Covers environmental and sustainability risks, as well as the actual or potential impacts identified through audits, inspections, or reporting mechanisms. | |

| B5 | Good Practices and Innovations | Focuses on identified good practices, innovative approaches, and lessons learned that enhance the effectiveness and impact of environmental audits and sustainability policies. | |

| Procedural | P1 | Audit Methodology | Refers to the design, techniques, and analytical tools used in conducting environmental audits and sustainability assurance engagements. |

| P2 | Data Collection and Evidence | Refers to methods of obtaining, validating, and managing information and empirical evidence used in environmental or sustainability audits. | |

| P3 | Follow-up and Recommendations | Refers to actions taken after audit completion to ensure that recommendations are addressed and improvements are achieved. | |

| P4 | Transparency and Disclosure | Refers to the disclosure and communication of audit results and related information to external audiences. | |

| P5 | Quality Assurance | Refers to procedures and institutional mechanisms that safeguard the reliability, validity, and professional integrity of environmental audits. |

Appendix B

| ID | Description | Type | Tags |

|---|---|---|---|

| SU01 | Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/2772 of 31 July 2023 supplementing Directive (EU) 2013/34 as regards sustainability reporting standards (ESRS) (European Commission, 2023) | EU Law/Legal Framework | S1 Regulatory Framework |

| SU02 | EFRAG ESRS Set 1 XBRL Taxonomy (EFRAG, 2024) | Taxonomy/Digital Reporting Framework | S4 Resources and Capacity P2 Data Collection and Evidence |

| SU03 | EFRAG ESRS XBRL Taxonomy—Project page (Concluded) (EFRAG, n.d.) | Web Summary/EU Project | S2 Institutional Arrangements |

| SU04 | International Standard on Sustainability Assurance (ISSA) 5000—General Requirements for Sustainability Assurance Engagements (IAASB, 2024) | Assurance Standard | P1 Audit Methodology |

| SU05 | ISSA 5000 Implementation Guide (IAASB, 2025) | Guidance/Implementation Manual | P2 Data Collection and Evidence |

| SU06 | INTOSAI WGEA—Guidance on Environmental Auditing (INTOSAI WGEA, 2025) | Guidance/Audit Manual | P1 Audit Methodology |

| SU07 | INTOSAI WGEA—Publications: Studies & Guidelines Portal (WGS.co.id, n.d.) | Web Portal/Reference Source | P4 Transparency and Disclosure |

| SU08 | ETC/HE Report 2024-5: Status Report of Air Quality in Europe for Year 2023 (EEA/ETC-HE, 2024) | EEA/ETC Report | B3 Key Indicators and Metrics |

| SU09 | EEA Briefing: Europe’s Air Quality Status 2023 (EEA, 2023b) | Briefing/Policy Summary | B4 Risk and Impact Areas |

| SU10 | EEA Bathing Water Country Fact Sheets 2024 (EEA, 2025a) | Country Factsheets/Data Publication | B1 Audit Topics |

| SU11 | EEA Report 02/2023—Tracking Waste Prevention Progress (EEA, 2023c) | EEA Report/Circular Economy | B2 Objectives and Findings |

| SU12 | EEA Waste Prevention Country Fact Sheets 2023 (EEA, 2023a) | Country Factsheets | B3 Key Indicators and Metrics |

| SU13 | EEA Briefing: Water Savings for a Water-Resilient Europe, 2025 (EEA, 2025b) | Briefing/Policy | B5 Good Practices and Innovations |

| SU14 | EEA Environmental Statement 2023 (EMAS) (EEA, 2024b) | EMAS Statement/Verified Disclosure | P5 Quality Assurance |

| ID | Description | Type | Tags |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD01 | Law on Environmental Protection No. 1515-XII (1993, consolidated 2014, amended 2023) (CIS LEGISLATION, 2023) | National Law/Legal Framework | S1 Regulatory Framework |

| MD02 | Court of Accounts of the Republic of Moldova—Environmental Audit Methodology (INTOSAI-Donor Cooperation, 2019) | Methodological Guideline | S2 Institutional Arrangements P1 Audit Methodology P3 Follow-up and Recommendations |

| MD03 | National Development Strategy “Moldova Europeană 2030” (Government of the Republic of Moldova, 2022a) | Policy/Strategy | S3 Mandate and Scope |

| MD04 | National Assessment Report for Moldova (2023) (Ministry of Environment of Moldova, 2023) | National Environmental Assessment Report | B4 Risk and Impact Areas |

| MD05 | Project Feasibility Assessment—Moldova Solid Waste Project (Final Report) of the Ministry of Environment of the Republic of Moldova/Consultant COWI A/S (COWI A/S, 2022) | Feasibility Study/Project Report | S2 Institutional Arrangements B3 Key Indicators and Metrics |

| MD06 | Low-Emission Development Programme of the Republic of Moldova until 2030 (Ministerul Justiției, 2023) | Government Decision/Climate Programme | S1 Regulatory Framework S3 Mandate and Scope |

| MD07 | The Environmental Compliance Assurance System in the Republic of Moldova: Current Situation and Recommendations (OECD & EU4Environment, 2022) | Assessment Report/Compliance Assurance Study | S1 Regulatory Framework P2 Data Collection and Evidence |

| MD08 | National Water Supply and Sanitation Strategy 2014–2030 (Government of the Republic of Moldova, 2022b) | National Strategy/Policy Framework | S3 Mandate and Scope |

| MD09 | Republic of Moldova’s First Biennial Transparency Report (BTR1) under the Paris Agreement (UNFCCC, 2025b) | Climate Transparency Report/National Submission | B2 Objectives and Findings P4 Transparency and Disclosure |

| MD10 | What Are Environmental Certificates in Moldova and Why Moldovan Environmental Regulations 2026 Demand Them? (About Moldova, 2025) | Media/Analytical Article | S4 Resources and Capacity B5 Good Practices and Innovations |

| ID | Description | Type | Tags |

|---|---|---|---|

| BG01 | Accounting Act (Ministry of Finance, 2025) | National Law/Legal Framework | S1 Regulatory Framework |

| BG02 | Environmental Protection Act (MoEW, 2024) | National Law/Legal Framework | S1 Regulatory Framework |

| BG03 | Public Enterprises Act and its Implementation Rules (Government of Bulgaria, 2020) | National Law/Corporate Governance Framework | S2 Institutional Arrangements |

| BG04 | National Strategy for the Environment 2020–2030 | Policy/Strategy | B2 Objectives and Findings |

| BG05 | Operational Programme “Environment”—Annual Implementation Report 2023 (Operational Programme “Environment”, 2023) | Programme Report | B3 Key Indicators and Metrics |

| BG06 | Implementation Report Format for the Aarhus Convention 2021 (MoEW, 2021) | Implementation Report | S3 Mandate and Scope |

| BG07 | National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan 2019–2030 (MoEW, 2019) | Climate Strategy/Policy Plan | B2 Objectives and Findings |

| BG08 | Supreme Audit Institution (NAO)—Joint Report on Plastic Waste Management (2022) | Performance Audit/Thematic Audit | S5 Cross-border or Regional Cooperation B3 Key Indicators and Metrics |

| BG09 | Audit “Protection, Restoration and Sustainable Management of Forests” (2021–2023) | Performance Audit | B4 Risk and Impact Areas |

| BG10 | Executive Environment Agency—EMAS Register 2024 | Registry/Database | P4 Transparency and Disclosure |

References

- About Moldova. (2025). What are environmental certificates in Moldova and why Moldovan environmental regulations 2026 demand them? Available online: https://aboutmoldova.md/en/view_articles_post.php?id=396 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Atanasova, A., & Naydenov, K. (2025). Perceptions of the barriers to the implementation of a successful climate change policy in Bulgaria. Climate, 13(2), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, A. K. M., Yang, Y.-F., Wang, H., Chen, R.-H., & Zheng, L. J. (2023). Mapping the landscape of ESG strategies: A bibliometric review and recommendations for future research. Sustainability, 15(24), 16592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O. (2012). ISO 9000 and organizational effectiveness: A systematic review. Quality Management Journal, 19(3), 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, M. K., Lajuni, N., Wellfren, A. C., & Lim, T. S. (2022). Sustainability reporting through environmental, social, and governance: A bibliometric review. Sustainability, 14(19), 12071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozhinova, M., & Nikolov, E. (2021, August 21). Integration of non-financial reporting in the Bulgarian most traded companies. 21st International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM (Volume 5, pp. 749–755), Albena, Bulgaria. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, K.-C., Zhu, J., Lan, H.-R., Lu, Y., Liu, R.-Y., & Liu, P. (2022). Effectiveness of government environmental auditing in the industrial manufacturing structure upgradation. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 995310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIS LEGISLATION. (2023). Law of the Republic of Moldova “about environmental protection”. Available online: https://cis-legislation.com/document.fwx?rgn=3317 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- COWI A/S. (2022). Project feasibility assessment—Moldova solid waste project (final report). COWI A/S. [Google Scholar]

- EEA. (2023a). 2023 waste prevention country fact sheets. European Environment Agency. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/waste/waste-prevention/countries/2023-waste-prevention-country-fact-sheets (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- EEA. (2023b, April 24). Europe’s air quality status 2023. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/europes-air-quality-status-2023 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- EEA. (2023c, May 17). Tracking waste prevention progress. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/tracking-waste-prevention-progress (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- EEA. (2024a). Consolidated annual activity report 2023 (CAAR). Copenhagen: European Environment Agency (EEA). Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/about/working-practices/docs-register/consolidated-annual-activity-report-2023-caar (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- EEA. (2024b, October 17). Environmental statement 2023. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/environmental-statement-2023 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- EEA. (2025a, June 20). Bathing water country fact sheets 2024. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/bathing-water/state-of-bathing-water/bathing-water-country-factsheets-2024 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- EEA. (2025b, June 4). Water savings for a water-resilient Europe. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/water-savings-for-a-water-resilient-europe (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- EEA/ETC-HE. (2024). ETC/HE report 2024-5: Status report of air quality in Europe 2024. European Environment Agency. Available online: https://www.eionet.europa.eu/etcs/etc-he/products/etc-he-products/etc-he-reports/etc-he-report-2024-5-status-report-of-air-quality-in-europe-for-year-2023-using-validated-and-up-to-date-data (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- EFRAG. (n.d.). ESRS XBRL taxonomy, concluded|EFRAG. Available online: https://www.efrag.org/en/projects/esrs-xbrl-taxonomy/concluded (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- EFRAG. (2024, August 30). ESRS digital taxonomy (XBRL): Exposure draft and implementation guidance. Available online: https://www.efrag.org/en/news-and-calendar/news/efrag-publishes-the-esrs-set-1-xbrl-taxonomy (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- European Commission. (2019). The European green deal (COM/2019/640 final). European Commission. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0640 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- European Commission. (2023). Commission delegated regulation (EU) 2023/2772 on european sustainability reporting standards (ESRS). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2023/2772/2023-12-22/eng (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Farooq, M. B., & de Villiers, C. (2017). The market for sustainability assurance services: A comprehensive literature review and future avenues for research. Pacific Accounting Review, 29(1), 79–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayad, A. A. S., Khatib, S. F. A., Alomair, A., & Al Naim, A. S. (2024). audit chair characteristics and ESG disclosure: Evidence from the saudi stock market. Sustainability, 16, 11011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G., Busch, T., & Bassen, A. (2015). ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 5(4), 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Bulgaria. (2020). Public enterprises act and its implementation rules. Government of Bulgaria.

- Government of the Republic of Moldova. (2022a). National development strategy “Moldova Europeană 2030”. Government of the Republic of Moldova.

- Government of the Republic of Moldova. (2022b). National water supply and sanitation strategy 2014–2030. Government of the Republic of Moldova.

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IAASB. (2024). International standard on sustainability assurance (ISSA) 5000: General requirements for sustainability assurance engagements [Standard]. IAASB. Available online: https://www.iaasb.org/publications/international-standard-sustainability-assurance-5000-general-requirements-sustainability-assurance (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- IAASB. (2025, January 27). ISSA 5000 implementation guide|IAASB. Available online: https://www.iaasb.org/publications/issa-5000-implementation-guide (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- International Organization for Standardization. (2015). Environmental management systems—Requirements with guidance for use (ISO 14001:2015). International Organization for Standardization.

- INTOSAI-Donor Cooperation. (2019, April 2). Court of accounts of the Republic of Moldova and the Swedish national audit office for the period of 2018–2022. Available online: https://intosaidonor.org/project/court-of-accounts-of-the-republic-of-moldova-and-the-swedish-national-audit-office-for-the-period-of-2018-2020/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- INTOSAI WGEA. (2025). Guidance on environmental auditing. INTOSAI Working Group on Environmental Auditing. Available online: https://www.environmental-auditing.org/media/e1ch5sbm/intosai-wgea-guidance-environmental-auditing.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Knechel, W. R., & Salterio, S. E. (2016). Auditing: Assurance and risk (4th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsantonis, S., Pinney, C., & Serafeim, G. (2016). ESG integration in investment management: Myths and realities. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 28(2), 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasteva-Hristova, R., Diaconu, L., Krastev, B., & Georgieva, E. (2025). Environmental auditing, public finance, and risk: Evidence from Moldova and Bulgaria (2020–2025). Available online: https://osf.io/aw5dz/overview (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Tang, J., Feng, C., & Chen, Y. (2023). can government environmental auditing help to improve environmental quality? Evidence from China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuszak-Flejszman, A., & Paliwoda, B. (2022). Effectiveness and benefits of the eco-management and audit scheme: Evidence from Polish organisations. Energies, 15(2), 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerul Justiției. (2023). HG659/2023. Available online: https://www.legis.md/cautare/getResults?doc_id=139980&lang=ro (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Ministry of Environment of Moldova. (2023). National environmental assessment report for Moldova. Ministry of Environment of Moldova.

- Ministry of Finance. (2025). Accounting act (Закон за счетоводството). Ministry of Finance.

- MoEW. (2019). National climate change adaptation strategy and action plan 2019–2030. MoEW. Available online: https://www.moew.government.bg/static/media/ups/categories/attachments/Strategy%20and%20Action%20Plan%20-%20Full%20Report%20-%20%20ENd3b215dfec16a8be016bfa529bcb6936.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- MoEW. (2021). Implementation report format for the aarhus convention 2021. MoEW. [Google Scholar]

- MoEW. (2024). Environmental protection act (Закон за опазване на околната среда). MoEW. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, W. R. (2023). Finance must be defended: Cybernetics, neoliberalism and environmental, social, and governance (ESG). Sustainability, 15, 3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q., Diaz-Rainey, I., Kitto, A., McNeil, B. I., & Pittman, N. A. (2023). Scope 3 emissions: Data quality and machine learning prediction accuracy. PLoS Climate, 2(11), e0000208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). G20/OECD principles of corporate governance 2023. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2023/09/g20-oecd-principles-of-corporate-governance-2023_60836fcb/ed750b30-en.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- OECD & EU4Environment. (2022). Environmental compliance assurance system in the Republic of Moldova: Current situation and recommendations. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.eu4environment.org/app/uploads/2022/03/Environmental-compliance-assurance-system-in-the-Republic-of-Moldova.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Operational Programme “Environment”. (2023). Annual implementation report 2023. Operational Programme “Environment”. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzi, S., Venturelli, A., & Caputo, F. (2024). Restoring trust in sustainability reporting: The enabling role of the external assurance. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 68, 101437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, M. K., & Gendron, Y. (2015). Qualitative research in auditing: A methodological roadmap. AUDITING: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 34(2), 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-García, L., Zorio-Grima, A., & García-Benau, M. A. (2015). Stakeholder engagement, corporate social responsibility and integrated reporting: An exploratory study. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 22(5), 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Zhou, C., & Gan, Z. (2023). Green finance policy and ESG performance: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Sustainability, 15, 6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE. (2011). Environmental performance review: Republic of Moldova (ECE/CEP/171)—Full report. UNECE. Available online: https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/epr/epr_studies/ECE_CEP_171_En.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- UNECE. (2017). Environmental performance review: Bulgaria (ECE/CEP/181)—Synopsis. UNECE. Available online: https://unece.org/DAM/env/epr/epr_studies/Synopsis/ECE_CEP_181_Bulgaria_Synopsis.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- UNFCCC. (2025a). Bulgaria—2024 biennial transparency report (BTR1). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/645540 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- UNFCCC. (2025b). Republic of Moldova. 2024 biennial transparency report (BTR). BTR1. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/645300 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development (A/RES/70/1). United Nations. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Wang, W., Wang, Z., & Mei, Y. (2023). Have government environmental auditing contributed to the green transformation of Chinese cities? Heliyon, 9(12), e22709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- WGS.co.id. (n.d.). INTOSAI working group on environmental auditing (WGEA). Available online: https://www.wgea.org/publications/studies-guidelines/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Zairis, G., Liargovas, P., & Apostolopoulos, N. (2024). Sustainable finance and ESG importance: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Sustainability, 16(7), 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., & Wildemuth, B. M. (2009). Qualitative analysis of content. In Applications of social research methods to questions in information and library science (pp. 308–319). Libraries Unlimited. [Google Scholar]

| Strand of Literature | Representative Sources * | Core Finding | Identified Gap/Research Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assurance & sustainability reporting | (Pizzi et al., 2024) | External assurance improves credibility and decision usefulness of sustainability reports. | Converge assurance scope and criteria; integrate with internal control and risk management. |

| EMS/EMAS and organizational performance | (Matuszak-Flejszman & Paliwoda, 2022) | EMAS delivers benefits beyond ISO 14001 via verified statements and compliance reviews. | Scale EMAS-style verified disclosure cycles; evaluate causal links to outcomes. |

| Government environmental auditing (GEA) | (Chai et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023) | GEA correlates with greener development and pollutant reductions, with context-dependent effects. | Strengthen criteria publication, follow-up mechanisms, and performance focus. |

| Scope 3 and value-chain data quality | (Nguyen et al., 2023) | Data scarcity and supplier heterogeneity undermine comparability and assurance. | Develop sector protocols and primary data pipelines; enable digital traceability. |

| Standards & policy architecture (ISSA 5000; ESRS/XBRL) | (IAASB, 2024; European Commission, 2023; EFRAG, 2024) | Global assurance benchmark + EU digital reporting enable comparable, auditable data. | Operationalize interoperability; build capacity for digital tagging and analytics. |

| Digitalization & ESG analytics | (Au et al., 2023; EFRAG, 2024) | Bibliometric evidence of rapid ESG expansion; taxonomies support machine-readable data. | Harmonize datasets and metrics; align analytics with assurance assertations. |

| Transition & capacity in post-socialist contexts | (Atanasova & Naydenov, 2025; OECD & EU4Environment, 2022) | Institutional capacity and supranational anchoring condition audit impact. | Invest in risk-based planning, interoperable registries, and transparency portals. |

| Dimension | Description | Example Documents 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Structural | Legal and institutional frameworks defining scope, mandates, and digital infrastructures. | SU01, SU02, SU03, SU13 |

| Substantive | Thematic focus of environmental audits: air, water, waste, biodiversity, GHG emissions. | SU08–SU13 |

| Procedural | Methods, evidence collection, stakeholder engagement, and follow-up mechanisms. | SU04–SU07, SU14 |

| Dimension | Key Themes | Representative Codes 1 | Illustrative Documents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural | EU regulatory alignment, ESRS integration, XBRL taxonomy, digital auditability. | S1–S5 | SU01–SU03, SU13 |

| Substantive | Air quality, waste prevention, water resilience, national progress reports. | B1–B5 | SU08–SU13 |

| Procedural | Audit design, ISSA 5000 assurance principles, follow-up and transparency. | P1–P5 | SU04–SU07, SU14 |

| Dimension | Description | Example Documents 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Structural | National laws, strategies, and institutional arrangements defining the framework for environmental governance and audit mandates. | MD01, MD03, MD06, MD10 |

| Substantive | Thematic focus areas such as waste management, water, climate adaptation, and sustainability performance indicators. | MD04, MD05, MD07, MD10 |

| Procedural | Audit methodologies, follow-up mechanisms, data reporting, and transparency practices. | MD02, MD08, MD09 |

| Dimension | Key Themes | Representative Codes 1 | Illustrative Documents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural | Legal foundations (Environmental Protection Law), institutional coordination (Moldova 2030 Strategy), and low-emission policy integration. | S1–S5 | MD01, MD03, MD06, MD10 |

| Substantive | Waste management, environmental indicators, climate resilience, and circular-economy transition. | B1–B5 | MD04, MD05, MD07, MD10 |

| Procedural | National audit standards, evidence-based reporting, UNFCCC transparency mechanisms, and follow-up reviews. | P1–P5 | MD02, MD08, MD09 |

| Dimension | Description | Example Documents 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Structural | National laws, institutional arrangements, and strategic frameworks shaping the regulatory environment for environmental governance. | BG01, BG03, BG05, BG06 |

| Substantive | Thematic focus areas of environmental policy—waste, water, climate, biodiversity, and air quality. | BG04, BG07, BG08, BG10 |

| Procedural | Mechanisms of audit practice, data verification, reporting systems, and registry-based transparency. | BG02, BG09, BG10 |

| Dimension | Key Themes | Representative Codes 1 | Illustrative Documents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural | Legal mandates, governance structures, strategic planning, and EU cohesion alignment. | S1–S5 | BG01, BG03, BG05, BG06 |

| Substantive | Sectoral sustainability (air, water, waste, climate adaptation), policy evaluation, and risk indicators. | B1–B5 | BG04, BG07, BG08, BG10 |

| Procedural | Audit methods, follow-up evaluation, data registries, and EMAS-based transparency. | P1–P5 | BG02, BG09, BG10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diaconu, L.; Krastev, B.; Georgieva, E.; Krasteva-Hristova, R. Environmental Auditing, Public Finance, and Risk: Evidence from Moldova and Bulgaria. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120683

Diaconu L, Krastev B, Georgieva E, Krasteva-Hristova R. Environmental Auditing, Public Finance, and Risk: Evidence from Moldova and Bulgaria. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(12):683. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120683

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiaconu, Luminita, Biser Krastev, Elena Georgieva, and Radosveta Krasteva-Hristova. 2025. "Environmental Auditing, Public Finance, and Risk: Evidence from Moldova and Bulgaria" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 12: 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120683

APA StyleDiaconu, L., Krastev, B., Georgieva, E., & Krasteva-Hristova, R. (2025). Environmental Auditing, Public Finance, and Risk: Evidence from Moldova and Bulgaria. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(12), 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120683