Influence of FinTech Paylater, Financial Well Being, Behavioral Finance, and Digital Financial Literacy on MSME Sustainability in South Sumatera

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Research Location, Population, and Sample

- The business has been operating actively for at least two years.

- The business owner is familiar with or has used digital financial services such as mobile banking, e-wallets, or Paylater.

- The respondent agrees to participate and completes the questionnaire fully.

2.3. Types and Sources of Data

2.4. Operational Definition of Variables

- FinTech Paylater (FP) was measured through perceptions of accessibility, transaction speed, installment flexibility, and contribution to business liquidity (Lee & Shin, 2018; Thakor, 2020; Ozili, 2018).

- Financial Well Being (FW) was measured using indicators of financial management ability, financial satisfaction, financial calmness, and debt control (Netemeyer et al., 2018; Joo & Grable, 2004).

- Behavioral Finance (BF) captured behavioral biases such as overconfidence, loss aversion, and mental accounting (Barberis & Thaler, 2003; Pompian, 2017).

- Digital Financial Literacy (DFL) reflected the ability of business owners to understand, utilize, and maintain the security of digital financial applications (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014; OECD, 2023).

- Sustainability (SU) represented the level of business sustainability based on competitiveness, digital innovation, and financial resilience (Elkington, 1997; Setiawan & Nugroho, 2022).

2.5. Data Analysis, Validity, and Reliability

- Measurement Model Evaluation (Outer Model)This stage assessed the validity and reliability of construct indicators using the following criteria:

- Convergent validity: Average Variance Extracted (AVE) ≥ 0.50.

- Discriminant validity: Fornell–Larcker Criterion and Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) ≤ 0.90.

- Construct reliability: Composite Reliability (CR) ≥ 0.70 and Cronbach’s Alpha ≥ 0.70 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

- Structural Model Evaluation (Inner Model)This stage evaluated the strength of relationships among latent variables and the predictive power of the model. The following indicators were used:

- Coefficient of determination (R2) to measure the explanatory power of exogenous variables.

- Effect size (f2) to assess the relative influence of each variable.

- Predictive relevance (Q2) to evaluate the model’s predictive capability.

2.6. Hypothesis Testing

3. Results

3.1. Instrument Development Procedure

3.2. Survey Data and Descriptive Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Measurement Model Evaluation (Outer Model)

4.1.1. Indicator of Reliability and Convergent Validity

4.1.2. Discriminant Validity

4.1.3. Multicollinearity

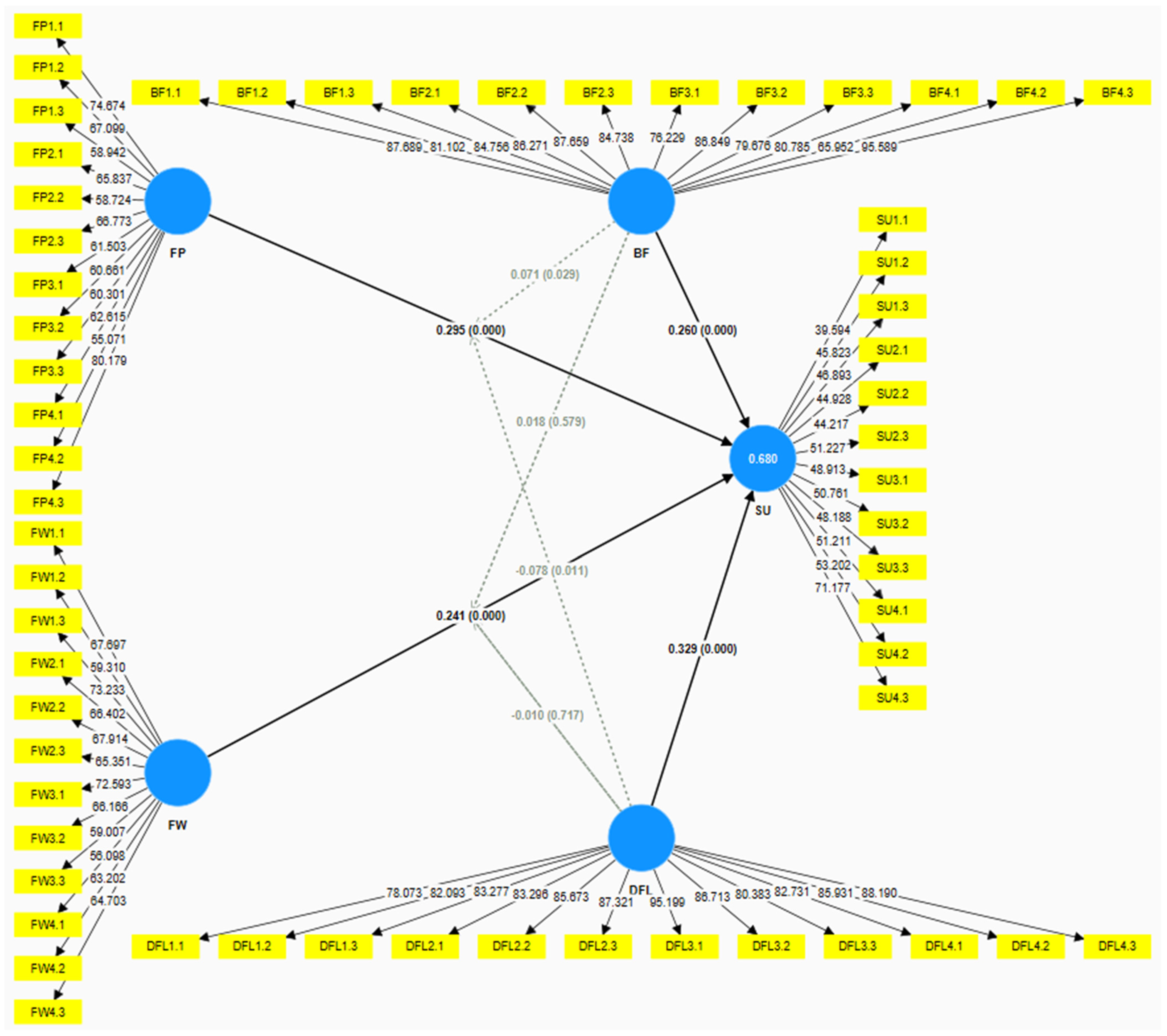

4.2. Structural Model Evaluation (Inner Model)

4.2.1. Coefficient of Determination

4.2.2. Effect Size (f2)

4.2.3. Model Fit Evaluation

4.2.4. Path Significance (Bootstrapping)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Shami, S. A., Damayanti, R., Adil, H., & Farhi, F. (2024). Financial and digital financial literacy through social media among SMEs. Heliyon, 10(5), e29712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badan Pusat Statistik. (2024). Profil industri mikro dan kecil 2023. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/id/publication/2024/09/18/52d85cbe9de005b6f5d69f95/profil-industri-mikro-dan-kecil-2023.html (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Bannier, C. E., & Schwarz, M. (2018). Who uses financial advisors? An empirical analysis of the demand for financial advice. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 148, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N. (2013). Thirty years of prospect theory in economics: A review and assessment. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(1), 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, N., & Thaler, R. (2003). A survey of behavioral finance. In Handbook of the economics of finance (Vol. 1, pp. 1053–1128). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BPS—Statistics Indonesia. (2024). Statistik Usaha Mikro, Kecil, dan Menengah (UMKM) 2024. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Bruggen, E. C., Hogreve, J., Holmlund, M., Kabadayi, S., & Lofgren, M. (2017). Financial well being: A conceptualization and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 79, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A. (2017, May 29–31). Financial technology transformation—Evidence from China’s value web. 31st International Academic Conference, London, UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–336). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Croy, G., Gerrans, P., & Speelman, C. (2010). The role and relevance of domain knowledge, perceptions of planning importance, and risk tolerance in predicting savings intentions. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31(6), 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Capstone Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomber, P., Kauffman, R. J., Parker, C., & Weber, B. W. (2017). On the fintech revolution: Interpreting the forces of innovation, disruption, and transformation in financial services. Journal of Management Information Systems, 35(1), 220–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, A., Kl"uhs, T., & Menkhoff, L. (2018). Does financial literacy improve financial inclusion? Cross-country evidence. World Development, 111, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2019). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S., & Grable, J. E. (2004). An exploratory framework of the determinants of financial satisfaction. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 25(1), 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kementerian Koperasi dan UKM Republik Indonesia. (2024). Statistik UMKM Indonesia 2024. Deputi Bidang UKM. [Google Scholar]

- Kementerian Perdagangan Republik Indonesia. (2023). Salinan Permendag 31 tahun 2023—PMSE-lengkap.

- Kock, N., & Lynn, G. S. (2012). Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13(7), 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I., & Shin, Y. J. (2018). Fintech: Ecosystem, business models, investment decisions, and challenges. Business Horizons, 61(1), 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A. (2019). Financial literacy and the need for financial education: Evidence and implications. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics, 155(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, O., & Lusardi, A. (2011). Financial literacy around the world: An overview. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 10, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, P. J., & Long, T. (2020). Financial literacy and digital financial literacy in developing countries. ADBI Working Paper Series 1010. Asian Development Bank Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, P. J., & Trinh, L. Q. (2019). Determinants and impacts of financial literacy in Cambodia and Viet Nam. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 12(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R. G., Warmath, D., Fernandes, D., & Lynch, J. G. (2018). How am I doing? Perceived financial well being, its potential antecedents, and its relation to overall well being. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(1), 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L., Nguyen, P. T., Tran, Q. N. N., & Trinh, T. T. G. (2021). Why does subjective financial literacy hinder retirement saving? The mediating roles of risk tolerance and risk perception. Review of Behavioral Finance, 14(5), 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2023). Green finance and sustainable investment: Policy framework for emerging economies. Available online: https://www.oecd.org (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (OJK). (2022). Survei Nasional Literasi dan Inklusi Keuangan (SNLIK) 2022. Available online: https://www.ojk.go.id (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Otoritas Jasa Keuangan (OJK). (2023). Laporan perkembangan fintech lending dan paylater di Indonesia tahun 2023. Available online: https://www.ojk.go.id (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Ozili, P. K. (2018). Impact of digital finance on financial inclusion and stability. Borsa Istanbul Review, 18(4), 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompian, M. M. (2017). Behavioral finance and wealth management: How to build optimal portfolios that account for investor biases (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Potrich, A. C. G., Vieira, K. M., & Kirch, G. (2016). Determinants of financial literacy: Analysis of the influence of socioeconomic and demographic variables. Revista Contabilidade & Finanças, 27(69), 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, M., & Robinson, D. T. (2007). Optimism and economic choice. Journal of Financial Economics, 86(1), 71–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnamasari, E. D. (2023). Digital financial literacy and financial behavior of MSMEs: Evidence from South Sumatera. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 10(2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, V., & Simon, H. K. (2015). What is behavioral finance? Business, Education & Technology Journal, 7(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, S., & Wagner, M. (2011). Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Business Strategy and the Environment, 20(4), 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, D., & Nugroho, A. (2022). FinTech adoption and MSME performance in Indonesia. International Journal of Business and Society, 23(2), 552–570. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, I. M., Sharma, R., & Kumar, A. (2020). Financial literacy, behavioral biases and financial well being: The mediating role of financial self-efficacy. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 19(5), 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shusha, A. F. (2017). The impact of behavioral factors on financial and investment decisions of small and medium-sized businesses. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 7(2), 524–536. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S., Jaiswal, A., Rai, A. K., & Kumar, A. (2024). Moderating role of fintech adoption on relationship between financial literacy and financial well-being. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 30, 7597–7607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolper, O. A., & Walter, A. (2017). Financial literacy, financial advice, and financial behavior. Journal of Business Economics, 87(5), 581–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakor, A. V. (2020). Fintech and banking: What do we know? Journal of Financial Intermediation, 41, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2022). Fintech and SME finance: Expanding responsible access. World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. J., & Porto, N. (2019). Financial education and satisfaction: The mediating role of financial literacy. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(7), 1441–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Business Location | Count | Per (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Lahat | 88 | 15.63 |

| Banyuasin | 87 | 15.45 |

| Muara Enim | 70 | 12.43 |

| OKI | 70 | 12.43 |

| Lubuk Linggau | 68 | 12.08 |

| Palembang | 60 | 10.66 |

| OI | 60 | 10.66 |

| Prabumulih | 60 | 10.66 |

| Gender | Count | Per (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 282 | 50.09 |

| Male | 281 | 49.91 |

| Age | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 21–30 | 200 | 35.52 |

| 31–40 | 150 | 26.64 |

| 41–50 | 120 | 21.31 |

| <20 | 50 | 8.88 |

| >50 | 43 | 7.64 |

| Last Education | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Senior High School | 180 | 31.97 |

| Bachelor’s | 180 | 31.97 |

| Diploma | 150 | 26.64 |

| Postgraduate | 53 | 9.41 |

| Years Operating | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 1–3 years | 180 | 31.97 |

| 4–6 years | 150 | 26.64 |

| >6 years | 133 | 23.62 |

| <1 years | 100 | 17.76 |

| Ownership Form | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Sole proprietorship | 563 | 53.29 |

| Partnership | 150 | 26.64 |

| Family business | 113 | 20.07 |

| Business Type | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Culinary | 200 | 35.52 |

| Fashion | 150 | 26.64 |

| Services | 120 | 21.31 |

| Handicraft | 93 | 16.52 |

| Monthly Turnover | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| <5 million | 150 | 26.64 |

| 5–10 million | 150 | 26.64 |

| 11–20 million | 150 | 26.64 |

| >20 million | 113 | 20.07 |

| Use Digital Services | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 400 | 71.05 |

| No | 163 | 28.95 |

| Paylater Usage | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 320 | 56.84 |

| No | 243 | 43.16 |

| Purpose of Paylater | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Working capital | 200 | 35.52 |

| Consumptive | 183 | 32.50 |

| Operational | 180 | 31.97 |

| Source of Financial Information | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Social Media | 200 | 35.52 |

| Friends | 150 | 26.64 |

| Family | 113 | 20.07 |

| Training | 100 | 17.76 |

| Financial Training Attendance | Count | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| No | 313 | 55.60 |

| Yes | 250 | 44.40 |

| No. | Code Questions | STS | TS | N | S | SS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | ||

| 1 | FP1.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 20 | 3.6% | 117 | 20.8% | 317 | 56.3% | 109 | 19.4% |

| 2 | FP1.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 23 | 4.1% | 114 | 20.2% | 303 | 53.8% | 123 | 21.8% |

| 3 | FP1.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 21 | 3.7% | 107 | 19.0% | 319 | 56.7% | 116 | 20.6% |

| 4 | FP2.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 21 | 3.7% | 117 | 20.8% | 299 | 53.1% | 126 | 22.4% |

| 5 | FP2.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 27 | 4.8% | 102 | 18.1% | 324 | 57.5% | 110 | 19.5% |

| 6 | FP2.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 27 | 4.8% | 105 | 18.7% | 292 | 51.9% | 139 | 24.7% |

| 7 | FP3.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 27 | 4.8% | 108 | 19.2% | 319 | 56.7% | 109 | 19.4% |

| 8 | FP3.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 24 | 4.3% | 107 | 19.0% | 316 | 56.1% | 116 | 20.6% |

| 9 | FP3.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 20 | 3.6% | 122 | 21.7% | 312 | 55.4% | 109 | 19.4% |

| 10 | FP4.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 18 | 3.2% | 117 | 20.8% | 316 | 56.1% | 112 | 19.9% |

| 11 | FP4.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 23 | 4.1% | 111 | 19.7% | 312 | 55.4% | 117 | 20.8% |

| 12 | FP4.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 23 | 4.1% | 112 | 19.9% | 299 | 53.1% | 129 | 22.9% |

| No. | Code Questions | STS | TS | N | S | SS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | ||

| 1 | FW1.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 18 | 3.2% | 113 | 20.1% | 323 | 57.4% | 109 | 19.4% |

| 2 | FW1.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 20 | 3.6% | 123 | 21.8% | 312 | 55.4% | 108 | 19.2% |

| 3 | FW1.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 19 | 3.4% | 123 | 21.8% | 308 | 54.7% | 113 | 20.1% |

| 4 | FW2.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 20 | 3.6% | 111 | 19.7% | 321 | 57.0% | 111 | 19.7% |

| 5 | FW2.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 19 | 3.4% | 114 | 20.2% | 326 | 57.9% | 104 | 18.5% |

| 6 | FW2.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 27 | 4.8% | 109 | 19.4% | 319 | 56.7% | 108 | 19.2% |

| 7 | FW3.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 25 | 4.4% | 98 | 17.4% | 332 | 59.0% | 108 | 19.2% |

| 8 | FW3.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 22 | 3.9% | 109 | 19.4% | 322 | 57.2% | 110 | 19.5% |

| 9 | FW3.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 22 | 3.9% | 113 | 20.1% | 311 | 55.2% | 117 | 20.8% |

| 10 | FW4.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 24 | 4.3% | 104 | 18.5% | 326 | 57.9% | 109 | 19.4% |

| 11 | FW4.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 23 | 4.1% | 105 | 18.7% | 321 | 57.0% | 114 | 20.2% |

| 12 | FW4.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 21 | 3.7% | 108 | 19.2% | 326 | 57.9% | 108 | 19.2% |

| No. | Code Questions | STS | TS | N | S | SS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | ||

| 1 | DFL1.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 33 | 5.9% | 155 | 27.5% | 272 | 48.3% | 103 | 18.3% |

| 2 | DFL1.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 31 | 5.5% | 145 | 25.8% | 284 | 50.4% | 103 | 18.3% |

| 3 | DFL1.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 36 | 6.4% | 141 | 25.0% | 283 | 50.3% | 103 | 18.3% |

| 4 | DFL2.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 24 | 4.3% | 154 | 27.4% | 294 | 52.2% | 91 | 16.2% |

| 5 | DFL2.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 29 | 5.2% | 149 | 26.5% | 291 | 51.7% | 94 | 16.7% |

| 6 | DFL2.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 30 | 5.3% | 146 | 25.9% | 296 | 52.6% | 91 | 16.2% |

| 7 | DFL3.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 31 | 5.5% | 154 | 27.4% | 286 | 50.8% | 92 | 16.3% |

| 8 | DFL3.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 35 | 6.2% | 145 | 25.8% | 280 | 49.7% | 103 | 18.3% |

| 9 | DFL3.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 30 | 5.3% | 147 | 26.1% | 288 | 51.2% | 98 | 17.4% |

| 10 | DFL4.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 35 | 6.2% | 144 | 25.6% | 281 | 49.9% | 103 | 18.3% |

| 11 | DFL4.2 | 1 | 0.2% | 31 | 5.5% | 146 | 25.9% | 288 | 51.2% | 97 | 17.2% |

| 12 | DFL4.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 32 | 5.7% | 146 | 25.9% | 282 | 50.1% | 103 | 18.3% |

| No. | Code Questions | STS | TS | N | S | SS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | ||

| 1 | BF1.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 33 | 5.9% | 161 | 28.6% | 265 | 47.1% | 104 | 18.5% |

| 2 | BF1.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 32 | 5.7% | 159 | 28.2% | 269 | 47.8% | 103 | 18.3% |

| 3 | BF1.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 25 | 4.4% | 173 | 30.7% | 267 | 47.4% | 98 | 17.4% |

| 4 | BF2.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 31 | 5.5% | 149 | 26.5% | 281 | 49.9% | 102 | 18.1% |

| 5 | BF2.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 34 | 6.0% | 151 | 26.8% | 279 | 49.6% | 99 | 17.6% |

| 6 | BF2.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 30 | 5.3% | 157 | 27.9% | 275 | 48.8% | 101 | 17.9% |

| 7 | BF3.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 27 | 4.8% | 158 | 28.1% | 275 | 48.8% | 103 | 18.3% |

| 8 | BF3.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 30 | 5.3% | 153 | 27.2% | 279 | 49.6% | 101 | 17.9% |

| 9 | BF3.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 30 | 5.3% | 162 | 28.8% | 267 | 47.4% | 104 | 18.5% |

| 10 | BF4.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 27 | 4.8% | 160 | 28.4% | 273 | 48.5% | 103 | 18.3% |

| 11 | BF4.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 30 | 5.3% | 148 | 26.3% | 278 | 49.4% | 107 | 19.0% |

| 12 | BF4.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 30 | 5.3% | 155 | 27.5% | 273 | 48.5% | 105 | 18.6% |

| No. | Code Questions | STS | TS | N | S | SS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | ||

| 1 | SU1.1 | 2 | 0.4% | 25 | 4.4% | 101 | 17.9% | 341 | 60.6% | 94 | 16.7% |

| 2 | SU1.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 30 | 5.3% | 116 | 20.6% | 323 | 57.4% | 94 | 16.7% |

| 3 | SU1.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 27 | 4.8% | 118 | 21.0% | 325 | 57.7% | 93 | 16.5% |

| 4 | SU2.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 27 | 4.8% | 115 | 20.4% | 327 | 58.1% | 94 | 16.7% |

| 5 | SU2.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 28 | 5.0% | 123 | 21.8% | 311 | 55.2% | 101 | 17.9% |

| 6 | SU2.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 34 | 6.0% | 110 | 19.5% | 318 | 56.5% | 101 | 17.9% |

| 7 | SU3.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 24 | 4.3% | 103 | 18.3% | 336 | 59.7% | 100 | 17.8% |

| 8 | SU3.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 27 | 4.8% | 108 | 19.2% | 322 | 57.2% | 106 | 18.8% |

| 9 | SU3.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 28 | 5.0% | 113 | 20.1% | 322 | 57.2% | 100 | 17.8% |

| 10 | SU4.1 | 0 | 0.0% | 24 | 4.3% | 110 | 19.5% | 327 | 58.1% | 102 | 18.1% |

| 11 | SU4.2 | 0 | 0.0% | 31 | 5.5% | 105 | 18.7% | 320 | 56.8% | 107 | 19.0% |

| 12 | SU4.3 | 0 | 0.0% | 26 | 4.6% | 110 | 19.5% | 325 | 57.7% | 102 | 18.1% |

| Construct | Indicators | Loading | CR | AVE | Interpretasi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP | FP1–FP4 | >0.70 | 0.89 | 0.65 | Reliable and valid |

| FW | FW1–FW4 | >0.70 | 0.91 | 0.68 | Reliable and valid |

| DFL | DFL1–DFL4 | >0.70 | 0.88 | 0.64 | Reliable and valid |

| BF | BF1–BF4 | >0.70 | 0.87 | 0.62 | Reliable and valid |

| SU | SU1–SU4 | >0.70 | 0.92 | 0.7 | Reliable and valid |

| Relationship | HTMT | Criteria | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| FP–FW | 0.74 | <0.90 | Valid |

| FP–DFL | 0.68 | <0.90 | Valid |

| FW–DFL | 0.71 | <0.90 | Valid |

| DFL–SU | 0.79 | <0.90 | Valid |

| BF–SU | 0.77 | <0.90 | Valid |

| Construct | VIF Range | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| FP | 1.87–2.25 | No multicollinearity |

| FW | 2.15–2.42 | No multicollinearity |

| DFL | 1.95–2.18 | No multicollinearity |

| BF | 1.89–2.22 | No multicollinearity |

| SU | 2.28–2.40 | No multicollinearity |

| Endogenous | Predictor | VIF Range | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| BF | FP | 1 | No multicollinearity |

| DFL | FW | 1 | No multicollinearity |

| SU | FP, FW, DFL, BF | 1.36–1.42 | No multicollinearity |

| Endogenous Construct | R2 | Q2 | Interpretasi |

|---|---|---|---|

| BF | 0.42 | 0.29 | Moderate, Predictive |

| DFL | 0.37 | 0.25 | Moderate, Predictive |

| SU | 0.61 | 0.41 | Strong, Predictive |

| Path | f2 | Category | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| FP → SU | 0.18 | Sedang | Paylater contributes meaningfully to MSME sustainability. |

| FW → SU | 0.16 | Sedang | Financial Well Being significantly supports sustainability. |

| DFL → SU | 0.14 | Sedang | Digital Financial Literacy moderately influences sustainability. |

| BF → SU | 0.08 | Kecil | Financial behavior contributes modestly but significantly. |

| FP → BF | 0.20 | Sedang | FP strongly explains variation in financial behavior. |

| FW → DFL | 0.17 | Sedang | FW is an important determinant of higher DFL. |

| Indicator | Saturated Model | Estimated Model | Benchmark | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRMR | 0.031 | 0.031 | ≤0.08 (good fit) | Very good fit; SRMR well below 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999) |

| d_ULS | 1.718 | 1.728 | Lower is better | Low and consistent; small gap vs. theory (Henseler et al., 2015) |

| d_G | 0.717 | 0.717 | Lower is better | Small distance indicates good alignment (Henseler et al., 2015) |

| Chi-square | 2211.837 | 2214.270 | Lower is better; sample-size sensitive | High values expected with large N; not primary in PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 2019) |

| NFI | 0.933 | 0.933 | ≥0.90 (good fit) | Meets the acceptable fit threshold (Bentler & Bonett, 1980) |

| Hypothesis | Path | Path Coef | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | FP → SU | 0.291 | 0.000 | Supported (positive, significant) |

| H2 | FW → SU | 0.241 | 0.000 | Supported (positive, significant) |

| H3 | BF → SU | 0.260 | 0.000 | Supported (positive, significant) |

| H4 | DFL → SU | 0.329 | 0.000 | Supported (positive, significant) |

| H5 | FP → SU dimoderasi DFL | −0.078 | 0.011 | Supported (significant moderation) |

| H6 | FW → SU dimoderasi DFL | −0.010 | 0.717 | Not supported (ns) |

| H7 | FW → SU dimoderasi BF | 0.018 | 0.555 | Not supported (ns) |

| H8 | FP → SU dimoderasi BF | 0.017 | 0.029 | Supported (significant moderation) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Purnamasari, E.D.; Anggraini, L.D.; Faradillah. Influence of FinTech Paylater, Financial Well Being, Behavioral Finance, and Digital Financial Literacy on MSME Sustainability in South Sumatera. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120682

Purnamasari ED, Anggraini LD, Faradillah. Influence of FinTech Paylater, Financial Well Being, Behavioral Finance, and Digital Financial Literacy on MSME Sustainability in South Sumatera. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(12):682. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120682

Chicago/Turabian StylePurnamasari, Endah Dewi, Leriza Desitama Anggraini, and Faradillah. 2025. "Influence of FinTech Paylater, Financial Well Being, Behavioral Finance, and Digital Financial Literacy on MSME Sustainability in South Sumatera" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 12: 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120682

APA StylePurnamasari, E. D., Anggraini, L. D., & Faradillah. (2025). Influence of FinTech Paylater, Financial Well Being, Behavioral Finance, and Digital Financial Literacy on MSME Sustainability in South Sumatera. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(12), 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120682