Docetaxel and Ramucirumab as Subsequent Treatment After First-Line Immunotherapy-Based Treatment for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Study and Literature Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

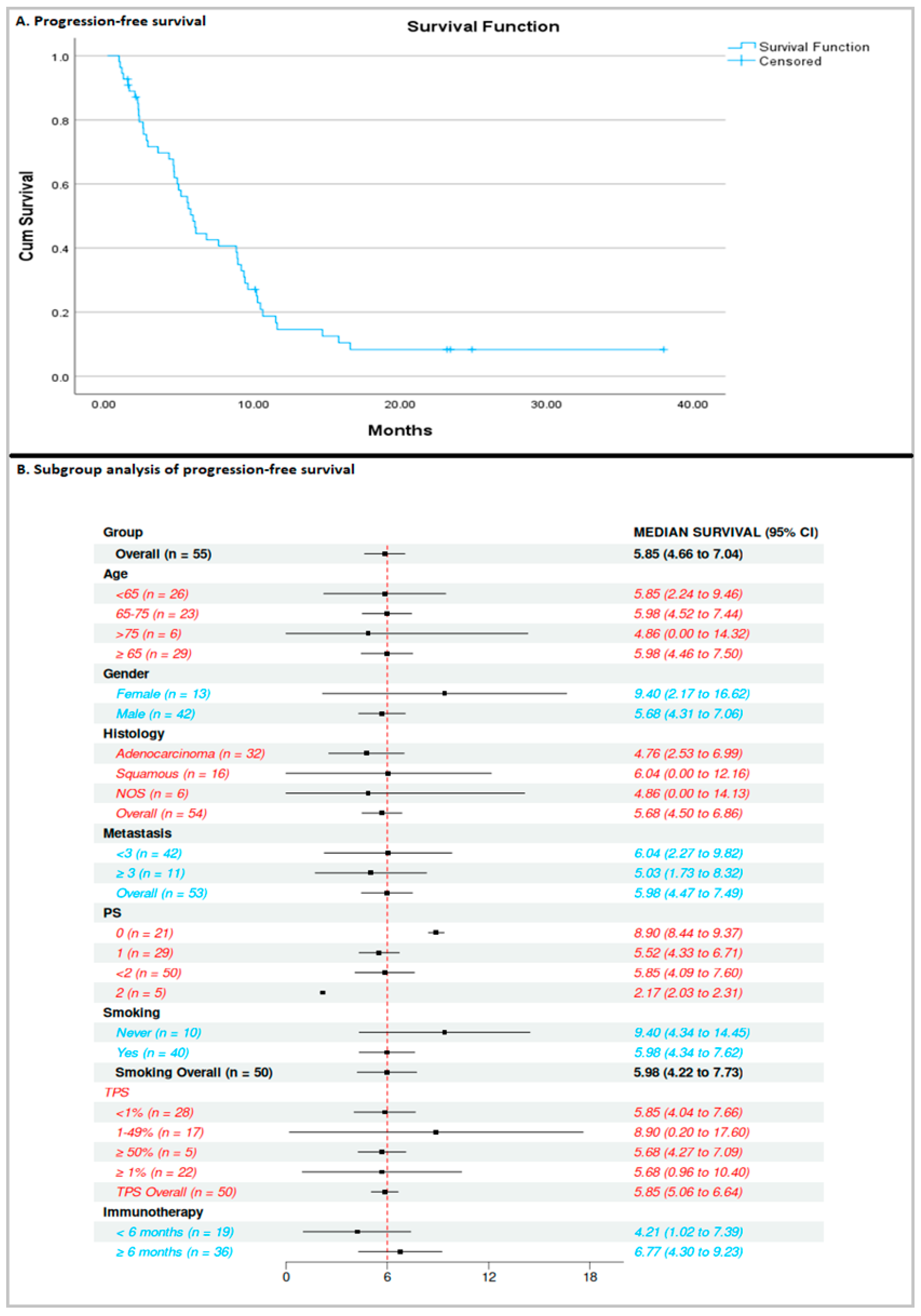

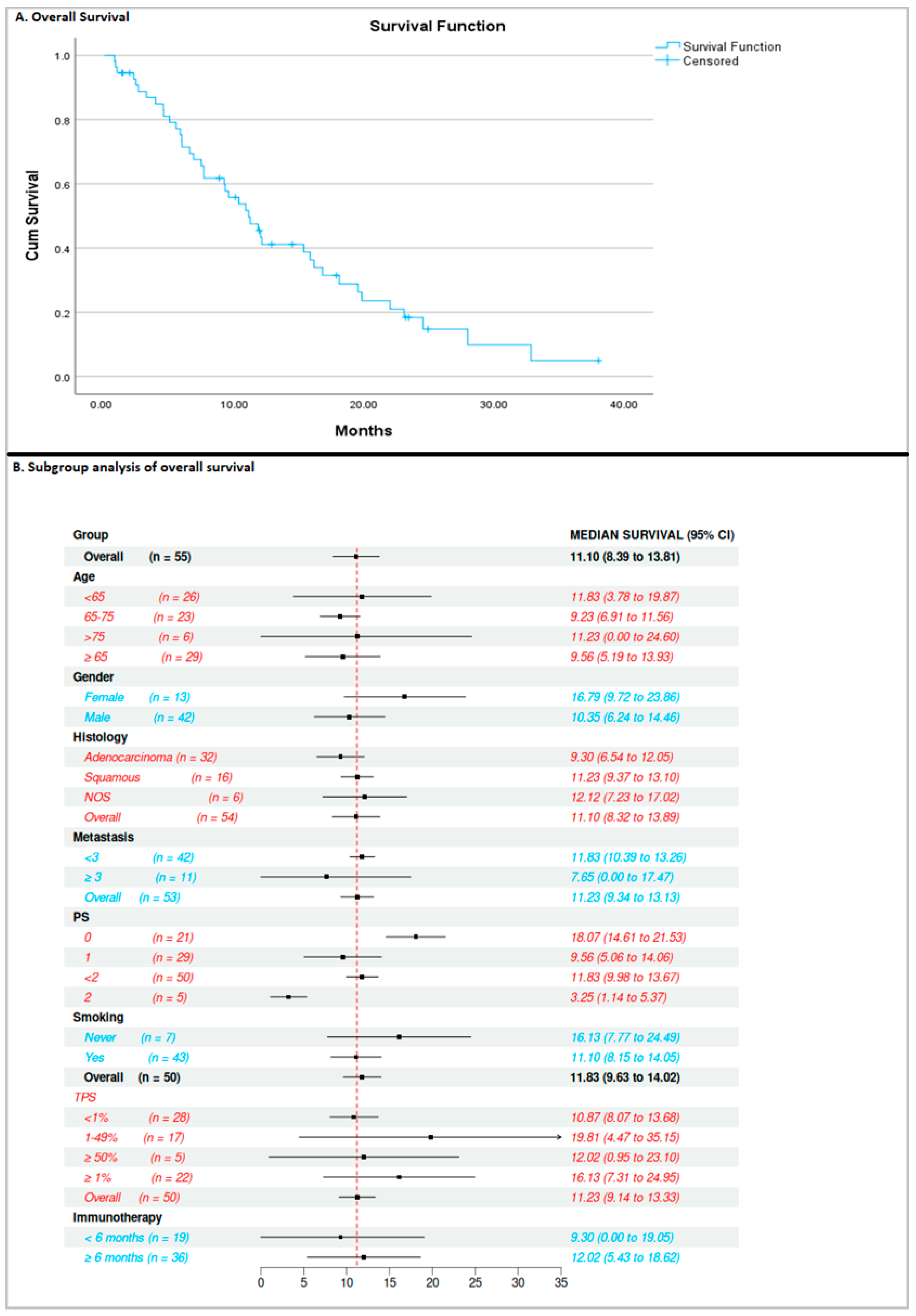

3.1. Efficacy of Docetaxel/Ramucirumab

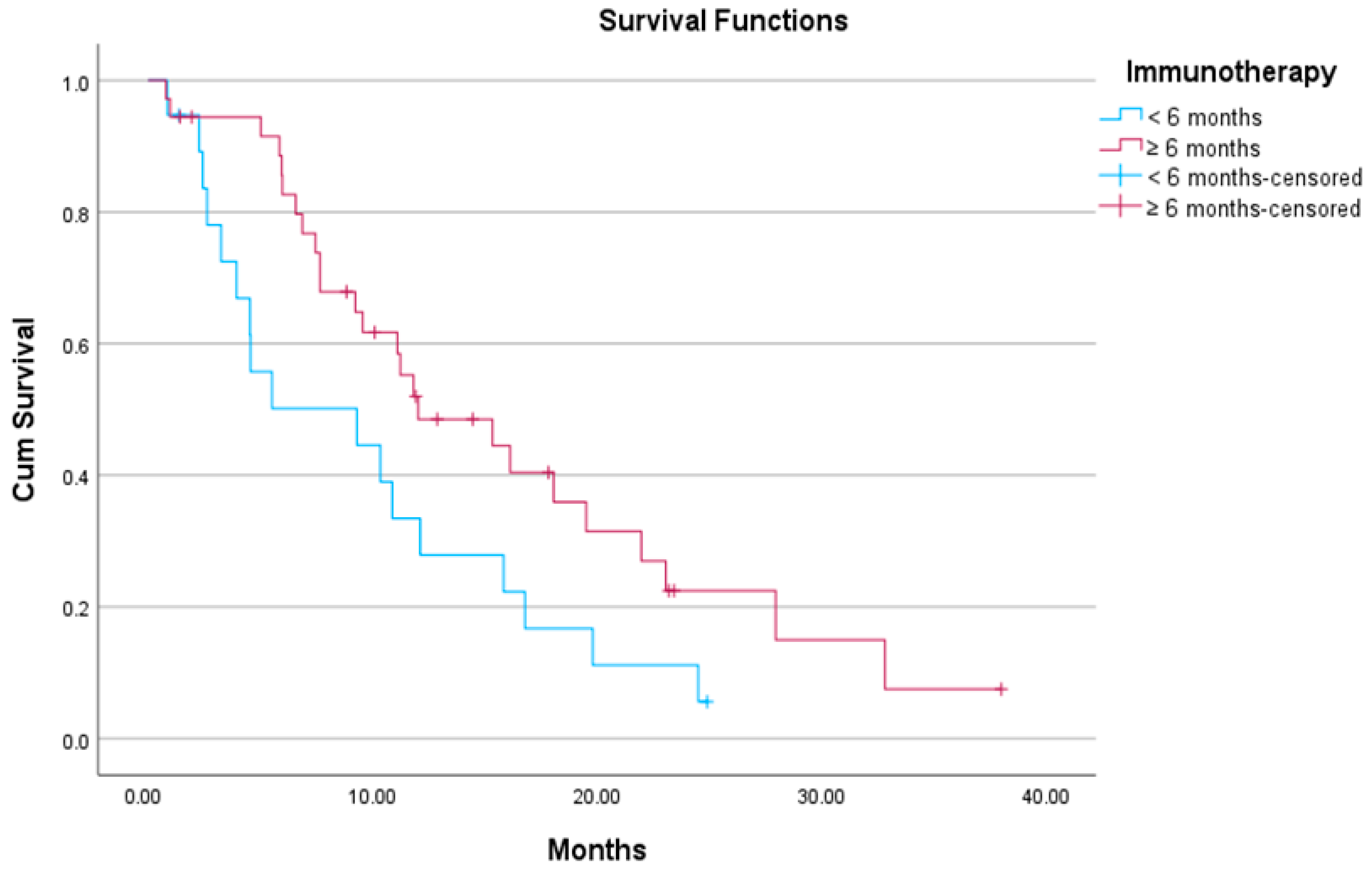

3.2. Association Between Exposure Time to Previous ICI-Based Therapy and Efficacy of Docetaxel/Ramucirumab

3.3. Response Rates for Docetaxel/Ramucirumab

3.4. Toxicity Profile

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gandhi, L.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Gadgeel, S.; Esteban, E.; Felip, E.; De Angelis, F.; Domine, M.; Clingan, P.; Hochmair, M.J.; Powell, S.F.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2078–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz-Ares, L.; Luft, A.; Vicente, D.; Tafreshi, A.; Gümüş, M.; Mazières, J.; Hermes, B.; Çay Şenler, F.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy for Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2040–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ares, L.; Ciuleanu, T.E.; Cobo, M.; Schenker, M.; Zurawski, B.; Menezes, J.; Richardet, E.; Bennouna, J.; Felip, E.; Juan-Vidal, O.; et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): An international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.L.; Cho, B.C.; Luft, A.; Alatorre-Alexander, J.; Geater, S.L.; Laktionov, K.; Kim, S.W.; Ursol, G.; Hussein, M.; Lim, F.L.; et al. Durvalumab With or Without Tremelimumab in Combination With Chemotherapy as First-Line Therapy for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: The Phase III POSEIDON Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1213–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R.S.; Giaccone, G.; de Marinis, F.; Reinmuth, N.; Vergnenegre, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Morise, M.; Felip, E.; Andric, Z.; Geater, S.; et al. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of PD-L1-Selected Patients with NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1328–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, M.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Robinson, A.G.; Hui, R.; Csőszi, T.; Fülöp, A.; Gottfried, M.; Peled, N.; Tafreshi, A.; Cuffe, S.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garon, E.B.; Ciuleanu, T.E.; Arrieta, O.; Prabhash, K.; Syrigos, K.N.; Goksel, T.; Park, K.; Gorbunova, V.; Kowalyszyn, R.D.; Pikiel, J.; et al. Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel for second-line treatment of stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum-based therapy (REVEL): A multicentre, double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2014, 384, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzawa, R.; Morise, M.; Ito, K.; Hataji, O.; Takahashi, K.; Koyama, J.; Kuwatsuka, Y.; Goto, Y.; Imaizumi, K.; Itani, H.; et al. Efficacy and safety of second-line therapy of docetaxel plus ramucirumab after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy plus immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer (SCORPION): A multicenter, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 66, 102303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katayama, Y.; Yamada, T.; Sawada, R.; Kawachi, H.; Morimoto, K.; Watanabe, S.; Watanabe, K.; Takeda, T.; Chihara, Y.; Shiotsu, S.; et al. Prospective Observational Study of Ramucirumab Plus Docetaxel After Combined Chemoimmunotherapy in Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Oncologist 2024, 29, e681–e689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Nagaoka, S.; Katayose, T.; Sekine, N. Safety and effectiveness of ramucirumab and docetaxel: A single-arm, prospective, multicenter, non-interventional, observational, post-marketing safety study of NSCLC in Japan. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2022, 21, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garon, E.B.; Visseren-Grul, C.; Rizzo, M.T.; Puri, T.; Chenji, S.; Reck, M. Clinical outcomes of ramucirumab plus docetaxel in the treatment of patients with non-small cell lung cancer after immunotherapy: A systematic literature review. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1247879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, A.; Yamaguchi, O.; Mori, K.; Miura, K.; Tamiya, M.; Oba, T.; Yanagitani, N.; Mizutani, H.; Ninomiya, T.; Kajiwara, T.; et al. Multicentre real-world data of ramucirumab plus docetaxel after combined platinum-based chemotherapy with programmed death-1 blockade in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: NEJ051 (REACTIVE study). Eur. J. Cancer 2023, 184, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, D.; Takata, K.; Mori, S.; Kozuki, T.; Takechi, Y.; Moriki, S.; Asakura, Y.; Ohno, T.; Nogami, N. Previous Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Treatment to Increase the Efficacy of Docetaxel and Ramucirumab Combination Chemotherapy. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 4987–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiono, A.; Kaira, K.; Mouri, A.; Yamaguchi, O.; Hashimoto, K.; Uchida, T.; Miura, Y.; Nishihara, F.; Murayama, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; et al. Improved efficacy of ramucirumab plus docetaxel after nivolumab failure in previously treated non-small cell lung cancer patients. Thorac. Cancer 2019, 10, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, A.; Yamada, T.; Okuma, Y.; Kitadai, R.; Takeda, T.; Kanematsu, T.; Goto, H.; Yoneda, H.; Harada, T.; Kubota, Y.; et al. Retrospective analysis of docetaxel in combination with ramucirumab for previously treated non-small cell lung cancer patients. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2019, 8, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, R.; Hayashi, H.; Chiba, Y.; Miyawaki, E.; Shimizu, J.; Ozaki, T.; Fujimoto, D.; Toyozawa, R.; Nakamura, A.; Kozuki, T.; et al. Propensity score-weighted analysis of chemotherapy after PD-1 inhibitors versus chemotherapy alone in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (WJOG10217L). J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozuka, T.; Kitazono, S.; Sakamoto, H.; Yoshida, H.; Amino, Y.; Uematsu, S.; Yoshizawa, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Ariyasu, R.; Uchibori, K.; et al. Addition of ramucirumab enhances docetaxel efficacy in patients who had received anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment. Lung Cancer 2020, 144, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueckl, W.M.; Reck, M.; Rittmeyer, A.; Kollmeier, J.; Wesseler, C.; Wiest, G.H.; Christopoulos, P.; Tufman, A.; Hoffknecht, P.; Ulm, B.; et al. Efficacy of Docetaxel Plus Ramucirumab as Palliative Third-Line Therapy Following Second-Line Immune-Checkpoint-Inhibitor Treatment in Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Stage IV. Clin. Med. Insights Oncol. 2020, 14, 1179554920951358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brueckl, W.M.; Reck, M.; Rittmeyer, A.; Kollmeier, J.; Wesseler, C.; Wiest, G.H.; Christopoulos, P.; Stenzinger, A.; Tufman, A.; Hoffknecht, P.; et al. Efficacy of docetaxel plus ramucirumab as palliative second-line therapy following first-line chemotherapy plus immune-checkpoint-inhibitor combination treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) UICC stage IV. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 3093–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawar, R.; Gawri, K.; Rodriguez, E.; Thammineni, V.; Saul, E.; Lima Filho, J.O.O.; Dempsey, N.; Khan, K.; Torres, T.; Kwon, D.; et al. P01.09 Improved Outcomes With Ramucirumab & Docetaxel in Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer After Failure of Immunotherapy. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16, S239–S240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, M.; Morimoto, K.; Yamada, T.; Shiotsu, S.; Chihara, Y.; Yamada, T.; Hiranuma, O.; Morimoto, Y.; Iwasaku, M.; Tokuda, S.; et al. Impact of docetaxel plus ramucirumab in a second-line setting after chemoimmunotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: A retrospective study. Thorac. Cancer 2022, 13, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, T.; Fujimoto, H.; Okano, T.; Naito, M.; Tsuji, C.; Iwanaka, S.; Sakakura, Y.; Yasuma, T.; D’Alessandro-Gabazza, C.N.; Oomoto, Y.; et al. Is the Efficacy of Adding Ramucirumab to Docetaxel Related to a History of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in the Real-World Clinical Practice? Cancers 2022, 14, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanizaki, S.; Matsumoto, K.; Tamiya, A.; Taniguchi, Y.; Matsuda, Y.; Uchida, J.; Ueno, K.; Kawachi, H.; Tamiya, M.; Yanase, T.; et al. Sequencing strategies with ramucirumab and docetaxel following prior treatments for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 79, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareff, S.A.; Gawri, K.; Khan, K.; Kwon, D.; Rodriguez, E.; Lopes, G.L.; Dawar, R. Efficacy and outcomes of ramucirumab and docetaxel in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer after disease progression on immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: Results of a monocentric, retrospective analysis. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1012783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, M.; Jiao, D.; Qin, S.; Chu, Q.; Wu, K.; Li, A. Synergistic effect of immune checkpoint blockade and anti-angiogenesis in cancer treatment. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumura, D.; Kloepper, J.; Amoozgar, Z.; Duda, D.G.; Jain, R.K. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using antiangiogenics: Opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Chen, J.; Wu, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, B.; Yao, J.; Zhong, H.; Li, J.; Cheng, Y.; Sun, Y.; et al. PL02.04 Phase 3 Study of Ivonescimab (AK112) vs. Pembrolizumab as First-line Treatment for PD-L1-positive Advanced NSCLC: Primary Analysis of HARMONi-2. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2024, 19, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckamp, K.L.; Redman, M.W.; Dragnev, K.H.; Minichiello, K.; Villaruz, L.C.; Faller, B.; Al Baghdadi, T.; Hines, S.; Everhart, L.; Highleyman, L.; et al. Phase II Randomized Study of Ramucirumab and Pembrolizumab Versus Standard of Care in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Previously Treated With Immunotherapy-Lung-MAP S1800A. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, N.; Ademuyiwa, F.O.; Cao, Z.A.; Chen, H.X.; Ferris, R.L.; Goldberg, S.B.; Hellmann, M.D.; Mehra, R.; Rhee, I.; Park, J.C.; et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) consensus definitions for resistance to combinations of immune checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e005920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grohé, C.; Wehler, T.; Dechow, T.; Henschke, S.; Schuette, W.; Dittrich, I.; Hammerschmidt, S.; Müller-Huesmann, H.; Schumann, C.; Krüger, S.; et al. Nintedanib plus docetaxel after progression on first-line immunochemotherapy in patients with lung adenocarcinoma: Cohort C of the non-interventional study, VARGADO. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2022, 11, 2010–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoi, K.; Yamada, T.; Morimoto, K.; Kawachi, H.; Tsutsumi, R.; Takeda, T.; Okada, A.; Tamiya, N.; Chihara, Y.; Shiotsu, S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Docetaxel plus Ramucirumab for Patients with Pretreated Advanced or Recurrent Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: Focus on Older Patients. Target. Oncol. 2024, 19, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K.; Tamiya, A.; Inagaki, Y.; Taniguchi, Y.; Matsuda, Y.; Kawachi, H.; Tamiya, M.; Tanizaki, S.; Uchida, J.; Ueno, K.; et al. Efficacy and safety of ramucirumab plus docetaxel in older patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A multicentre retrospective cohort study. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2022, 13, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahma, O.E.; Hodi, F.S. The Intersection between Tumor Angiogenesis and Immune Suppression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 5449–5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voron, T.; Colussi, O.; Marcheteau, E.; Pernot, S.; Nizard, M.; Pointet, A.L.; Latreche, S.; Bergaya, S.; Benhamouda, N.; Tanchot, C.; et al. VEGF-A modulates expression of inhibitory checkpoints on CD8+ T cells in tumors. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.A.; Nilsson, M.B.; Le, X.; Cascone, T.; Jain, R.K.; Heymach, J.V. Molecular Mechanisms and Future Implications of VEGF/VEGFR in Cancer Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, S.; Sho, M.; Yamato, I.; Yoshiji, H.; Wakatsuki, K.; Nishiwada, S.; Yagita, H.; Nakajima, Y. Simultaneous blockade of programmed death 1 and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) induces synergistic anti-tumour effect in vivo. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2013, 172, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.S.; Yang, H.; Chon, H.J.; Kim, C. Combination of anti-angiogenic therapy and immune checkpoint blockade normalizes vascular-immune crosstalk to potentiate cancer immunity. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rini, B.I.; Plimack, E.R.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Hawkins, R.; Nosov, D.; Pouliot, F.; Alekseev, B.; Soulières, D.; Melichar, B.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makker, V.; Colombo, N.; Casado Herráez, A.; Santin, A.D.; Colomba, E.; Miller, D.S.; Fujiwara, K.; Pignata, S.; Baron-Hay, S.; Ray-Coquard, I.; et al. Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab for Advanced Endometrial Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; Kaseb, A.O.; et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socinski, M.A.; Jotte, R.M.; Cappuzzo, F.; Orlandi, F.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Nogami, N.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Thomas, C.A.; Barlesi, F.; et al. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2288–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Amaladas, N.; O’Mahony, M.; Manro, J.R.; Inigo, I.; Li, Q.; Rasmussen, E.R.; Brahmachary, M.; Doman, T.N.; Hall, G.; et al. Treatment with a VEGFR-2 antibody results in intra-tumor immune modulation and enhances anti-tumor efficacy of PD-L1 blockade in syngeneic murine tumor models. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04340882 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Mouri, A.; Kaira, K.; Shiono, A.; Yamaguchi, O.; Murayama, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; Kagamu, H. Clinical significance of primary prophylactic pegylated-granulocyte-colony stimulating factor after the administration of ramucirumab plus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac. Cancer 2019, 10, 1005–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient Characteristics | Number of Patients = 55 (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, median(range) | 64.8 (36–80) |

| <65 | 22 (40) |

| 65–75 | 27 (49.1) |

| >75 | 6 (10.9) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 42 (76.4) |

| Female | 13 (23.6) |

| Performance Status | |

| 0 | 21 (38.2) |

| 1 | 29 (52.7) |

| 2 | 5 (9.1) |

| Histology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 32 (58.2) |

| Squamous | 16 (29.1) |

| NOS | 5 (9.1) |

| Other | 2 (3.6) |

| Smoking history | |

| Pack/years (median) | 53.7 |

| Active/Ex-smokers | 43 (78.2) |

| Never smokers | 7 (12.7) |

| N/A | 5 (9.1) |

| TPS | |

| <1% | 28 (50.9) |

| 1–49% | 17 (30.9) |

| >50% | 5 (9.1) |

| N/A | 5 (9.1) |

| Molecular profiling | |

| No mutations | 29 (52.7) |

| EGFR | 3 (5.4) |

| ALK | - |

| KRAS | 7 (12.7) |

| Other * | 13 (23.6) |

| N/A | 7 (12.7) |

| Sites of metastases | |

| ≥3 sites | 11 (20) |

| <3 sites | 42 (76.4) |

| Relapsed Stage III | 2 (3.6) |

| IO drug | |

| Pembrolizumab | 48 (87.4) |

| Nivolumab | 2 (3.6) |

| Atezolizumab | 2 (3.6) |

| Nivolumab/Ipilimumab | 3 (5.4) |

| Prior immunotherapy type of regimen | |

| Monotherapy | 7 (12.7) |

| Chemo-IO | 48 (87.3) |

| Docetaxel/Ramucirumab line of therapy | |

| Second | 46 (83.6) |

| Third or beyond | 9 (16.4) |

| Overall Response | N = 50 (%) |

|---|---|

| CR | - |

| PR | 21 (42) |

| SD | 17 (34) |

| PD | 12 (24) |

| ORR | 21/50 (42) |

| DCR | 38/50 (76) |

| Adverse Events | Grade 1–2, N (%) | Grade ≥ 3, N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Any | 51 (92.7) | 30 (54.5) |

| Malaise | 22 (40) | 6 (10.9) |

| Numbness | 13 (23.6) | 1 (1.8) |

| Diarrhea | 12 (21.8) | 4 (7.3) |

| Nausea | 6 (10.9) | 1 (1.8) |

| Epiphora | 6 (10.9) | - |

| Constipation | 5 (9.1) | - |

| Anorexia | 5 (9.1) | - |

| Cough | 5 (9.1) | - |

| Hypertension | 5 (9.1) | 1 (1.8) |

| Anemia | 4 (7.3) | 5 (9.1) |

| Mucositis | 4 (7.3) | - |

| Dysgeusia | 3 (5.4) | - |

| Hoarseness | 3 (5.4) | - |

| Alopecia | 2 (3.6) | - |

| Hypothyroidism | 2 (3.6) | - |

| Pruritus | 1 (1.8) | - |

| Vomiting | 1 (1.8) | - |

| Skin rah | 1 (1.8) | 3 (5.4) |

| Neutropenia | 1 (1.8) | 3 (5.4) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.8) |

| Febrile Neutropenia | - | 1 (1.8) |

| AESIs of Ramucirumab | ||

| Heart failure | 1 (1.8) | - |

| Bleeding or hemorrhage | ||

| Hemoptysis | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.8) |

| GI bleeding | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.8) |

| Epistaxis | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.8) |

| Menorrhagia | 1 (1.8) | - |

| Thromboembolic events | ||

| PE | 1 (1.8) | - |

| DVT | 1 (1.8) | - |

| Proteinuria | - | 1 (1.8) |

| Study’s First Author, Year of Publication [Reference] | Study Type | Number of Patients | PFS (Months) | OS (Months) | RR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harada, 2019 [12] | Retrospective, single center | 18 | 5.7 | 13.8 | 38.9 |

| Shiono, 2019 [13] | Retrospective, single center | 20 | 5.6 | 11.3 | 60 |

| Yoshimura, 2019 [14] | Retrospective, multicenter | 40 | 5.7 | 11.9 | NA |

| Kato, 2020 [15] | Retrospective, multicenter | 62 | 5.7 | 17.5 | 20.9 |

| Tozuka, 2020 [16] | Retrospective, single center | 21 | 5.9 | 19.8 | 42.6 |

| Brueckl, 2020 [18] | Retrospective, multicenter | 67 | 6.8 | 11 | 36 |

| Brueckl, 2021 [19] | Retrospective, multicenter | 77 | 3.9 | 7.5 | 32.5 |

| Dawar, 2021 [19] | Retrospective, single center | 35 | 6.6 | 20.9 | NA |

| Ishida, 2021 [20] | Retrospective, multicenter | 18 | 5.8 | 10.7 | 55.6 |

| Nishimura, 2022 [22] | Retrospective, single center | 17 | 2.4 | 7.2 | 57.1 |

| Tanizaki, 2023 [23] | Retrospective, multi-center | 94 | 5.8 | 13.4 | 31 |

| Chen, 2022 [10] | Prospective, multicenter | 154 | NA | 58.7% * | NA |

| Kareff, 2023 [24] | Retrospective, single center | 35 | 6.6 | 20.9 | NA |

| Matsuzawa, 2023 [8] | Phase II, single arm | 32 | 6.5 | 17.5 | 34.4 |

| Nakamura, 2023 [12] | Retrospective, multicenter | 288 | 4.1 | 11.6 | 28.8 |

| Katayama, 2024 [9] | Prospective, multicenter | 44 | 6.3 | 22.6 | 36.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loizidis, S.; Vogazianos, P.; Kordatou, Z.; Fotopoulos, G.; Orphanos, G.; Kyriakou, F.; Charalambous, H. Docetaxel and Ramucirumab as Subsequent Treatment After First-Line Immunotherapy-Based Treatment for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Study and Literature Review. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 612. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32110612

Loizidis S, Vogazianos P, Kordatou Z, Fotopoulos G, Orphanos G, Kyriakou F, Charalambous H. Docetaxel and Ramucirumab as Subsequent Treatment After First-Line Immunotherapy-Based Treatment for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Study and Literature Review. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(11):612. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32110612

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoizidis, Sotiris, Paris Vogazianos, Zoe Kordatou, Georgios Fotopoulos, George Orphanos, Flora Kyriakou, and Haris Charalambous. 2025. "Docetaxel and Ramucirumab as Subsequent Treatment After First-Line Immunotherapy-Based Treatment for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Study and Literature Review" Current Oncology 32, no. 11: 612. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32110612

APA StyleLoizidis, S., Vogazianos, P., Kordatou, Z., Fotopoulos, G., Orphanos, G., Kyriakou, F., & Charalambous, H. (2025). Docetaxel and Ramucirumab as Subsequent Treatment After First-Line Immunotherapy-Based Treatment for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Study and Literature Review. Current Oncology, 32(11), 612. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32110612