1. Case Presentation

Owing to a massive femoral haematoma several days after muscle biopsy (polymyositis), a 56-year old woman was readmitted to the hospital. She was on oral anticoagulation because of known paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Beside the atrial fibrillation, the patient’s previous cardiac history has been unobtrusive. Coronary angiography and echocardiography 18 months prior to the event showed no evidence of coronary artery or structural heart disease.

During hospitalisation, the patient complained of palpitations. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed a wide-complex tachycardia with a heart rate of 128 beats per minute (Figure 1a).

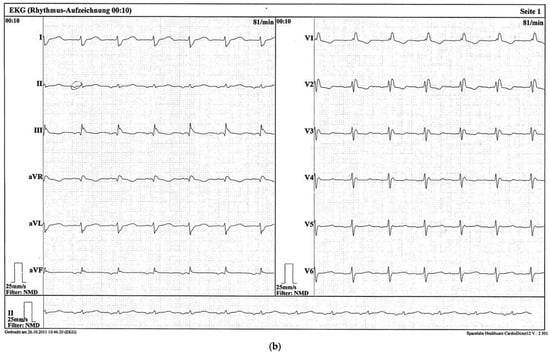

Figure 1.

(a) Standard 12-lead ECG showing wide-complex tachycardia (125 ms) with bifascicular block (RBBB + LPFB) morphology. (b) Standard 12-lead ECG registered one and a half years before the actual event. Bifascicular block (RBBB + LPFB) morphology is present already, in addition, the ECG shows an ectopic atrial rhythm.

2. Questions

- What is the rhythm in the 12-lead ECG (differential diagnosis)?

- How would you confirm the diagnosis?

3. Commentary

The ECG shows a regular wide-complex tachycardia with a QRS duration of 125 ms and a right bundle-branch block (RBBB) morphology. In addition, the ECG also shows right axis deviation, which was interpreted as an accompanying left posterior fascicular block (LPFB), since no other reasons for right axis deviation were present. The differential diagnosis of the arrhythmia includes ventricular tachycardia (VT) and supraventricular tachycardias (with aberrant conduction or permanent bundle-branch block). In particular, 2:1 atrial flutter (AFlu), atrioventricular (nodal) reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT/AVRT) and atrial tachycardia (AT) should be suspected. Atrial fibrillation is unlikely because of the regular rhythm.

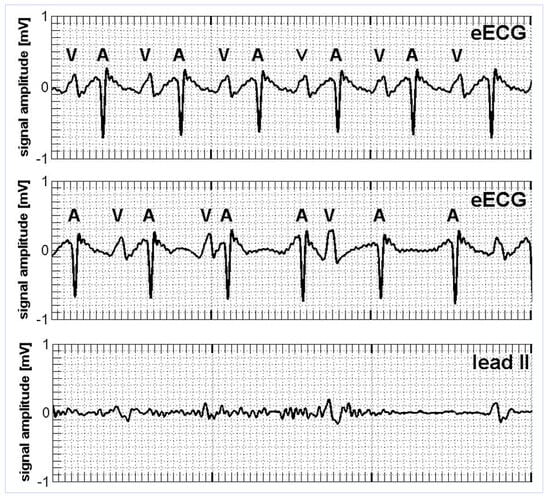

Since the ECG shows a wide-complex tachycardia, VT must be ruled out first. Pathognomonic findings for VT like fusion beats or V-A dissociation with a faster ventricular rate were not observed. Morphological criteria indicating a VT in RBBB pattern wide-complex tachycardia [1] are lacking and the QRS complex is still relatively narrow, both of which favour a supraventricular origin of the tachycardia. In addition, a former ECG already showed a bifascicular block (RBBB + LPFB) morphology during A-V sequential rhythm from the low right atrium (Figure 1b). To unveil the exact mechanism of the arrhythmia, careful analysis of the atrial activity is crucial [2]. In the attached 12-lead ECG, P-waves are unapparent. In such cases, an AVNRT may be most commonly expected [2]. To confirm the diagnosis, we performed an oesophageal ECG (eECG, Figure 2, top panel). The eECG showed constant 1:1 AV association with a V-A interval >200 ms. Thus, 2:1 atrial flutter, atrial fibrillation and a typical AVNRT (with fast retrograde conduction) could be ruled out. To further distinguish between atypical AVNRT (slow retrograde conduction with long V-A interval), AT and AVRT, we administered an IV bolus of 6 mg of adenosine during continuous eECG monitoring (Figure 2, middle and bottom panels). A transient AV-block occurred while the atrial tachycardia persisted. Therefore, a reentry circuit involving the AV node cannot be the underlying mechanism of the arrhythmia, which further rules out an atypical AVNRT or AVRT. Thus, the final diagnosis is a sustained atrial tachycardia.

Figure 2.

Oesophageal ECG during tachycardia (top panel). Simultaneous registration of the oesophageal ECG (middle panel) and a rhythm strip (lead II, bottom panel) after administration of adenosine. Transient AV block occurs, whereas the atrial tachycardia persists. After adenosine administration, the patient experienced dyspnoea and chest pain, which made her move her arms and resulted in poor signal quality of the rhythm strip.

For rate control, the patient received metoprolol up to 200 mg/day. In addition, she received verapamil and digoxin. However, the arrhythmia did not terminate. Therefore, the patient underwent DC cardioversion with successful conversion into sinus rhythm.

Two weeks later, the AT recurred; the patient is now planned to undergo an invasive electrophysiological study and radiofrequency catheter ablation.

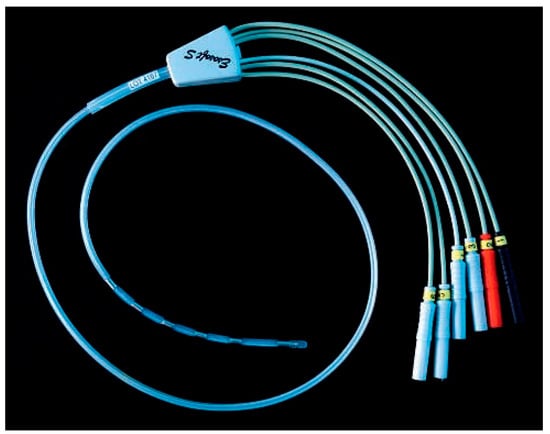

This report illustrates the potential of eECG to unveil the mechanism of narrow- or wide-complex tachycardias [2]. In haemodynamically stable patients, thorough diagnosis of the arrhythmia prior to cardioversion is desirable. An eECG recording can easily be obtained within a few minutes with a nasally inserted oesophageal ECG electrode (Figure 3). The eECG shows excellent atrial signals and the oesophageal probe is usually tolerated well without pharyngeal anaesthesia [3]. In general, atrial activity may also be unmasked on the standard ECG leads during adenosine administration. However, adenosine might be contraindicated and the rhythm strip recorded during adenosine administration may suffer from poor quality (Figure 2, bottom panel). The eECG as an elegant method, therefore, simplifies the differential diagnosis of tachyarrhythmias, in particular if no electrophysiologic laboratory is available.

Figure 3.

Hexapolar 9 French oesophageal ECG electrode (Esosoft S®, FIAB, It).

Funding

No financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- Brugada, P.; Brugada, J.; Mont, L.; Smeets, J.; Andries, E.W. A new approach to the differential diagnosis of a regular tachycardia with a wide QRS complex. Circulation 1991, 83, 1649–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomstrom-Lundqvist, C.; Scheinmann, M.M.; Aliot, E.M.; Alpert, J.S.; Calkins, H.; Camm, A.J.; et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias—Executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology committee for practice guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias) developed in collaboration with NASPE-Heart Rhythm Society. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 42, 1493–1531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haeberlin, A.; Niederhauser, T.; Marisa, T.; Goette, J.; Jacomet, M.; Mattle, D.; et al. The optimal lead insertion depth for esophageal ECG recordings with respect to atrial signal quality. J. Electrocardiol. 2013, 46, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2013 by the author. Attribution - Non-Commercial - NoDerivatives 4.0.