Beyond the Classroom: The Role of Social Connections and Family in Adolescent Mental Health in the Transylvanian Population of Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

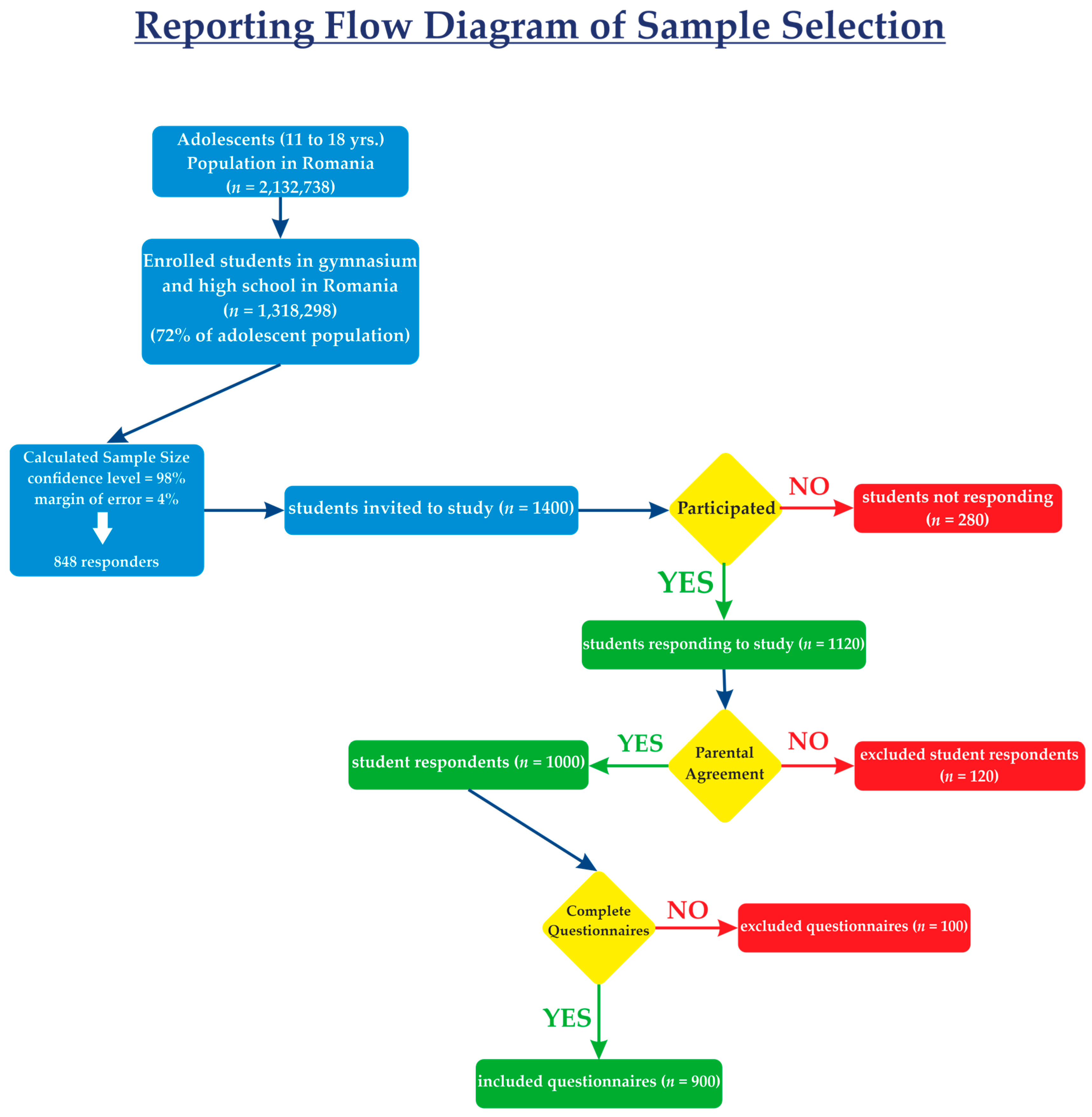

2.1. Population Selection and Study Design

2.2. Questionnaire Measurements and Data Collection

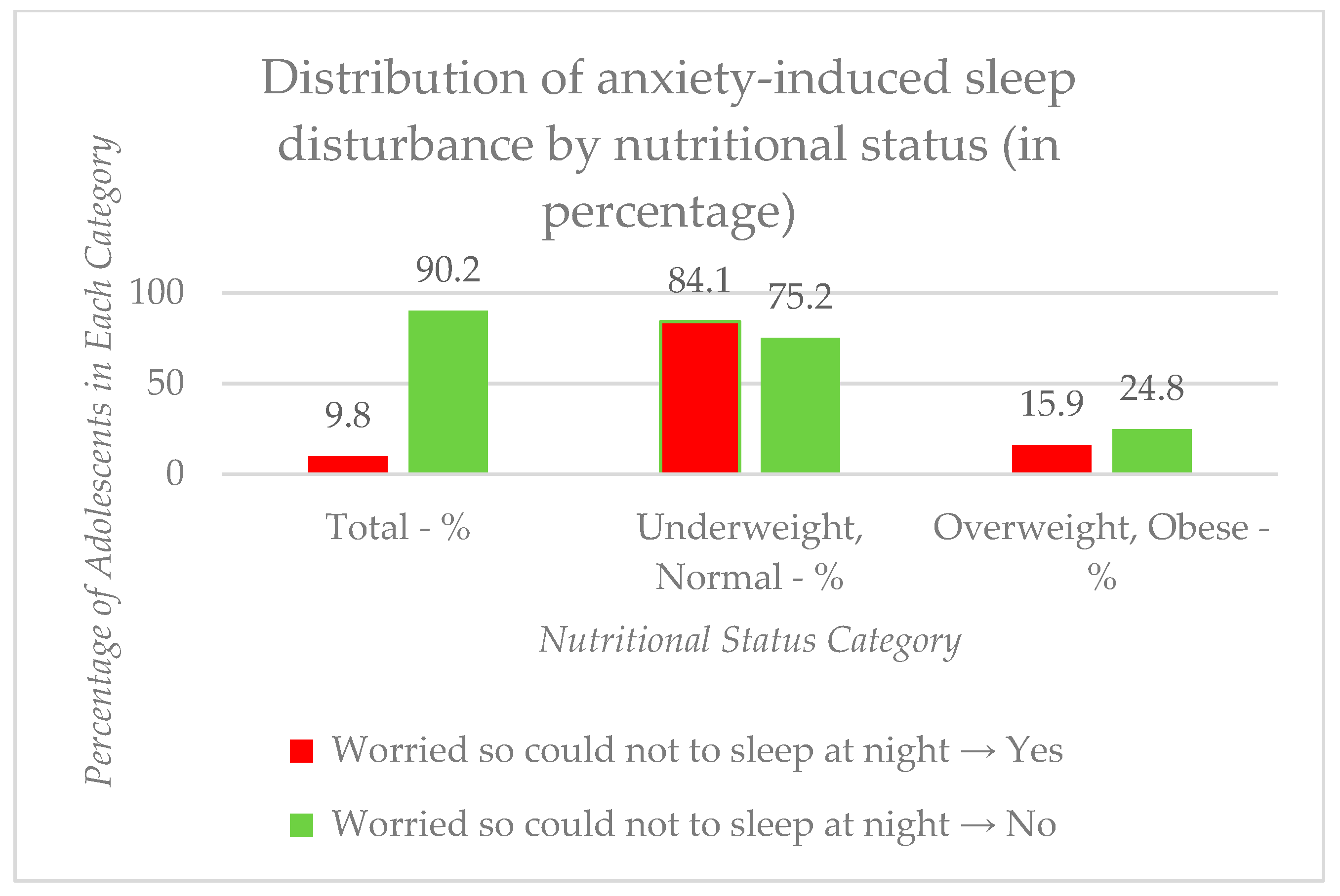

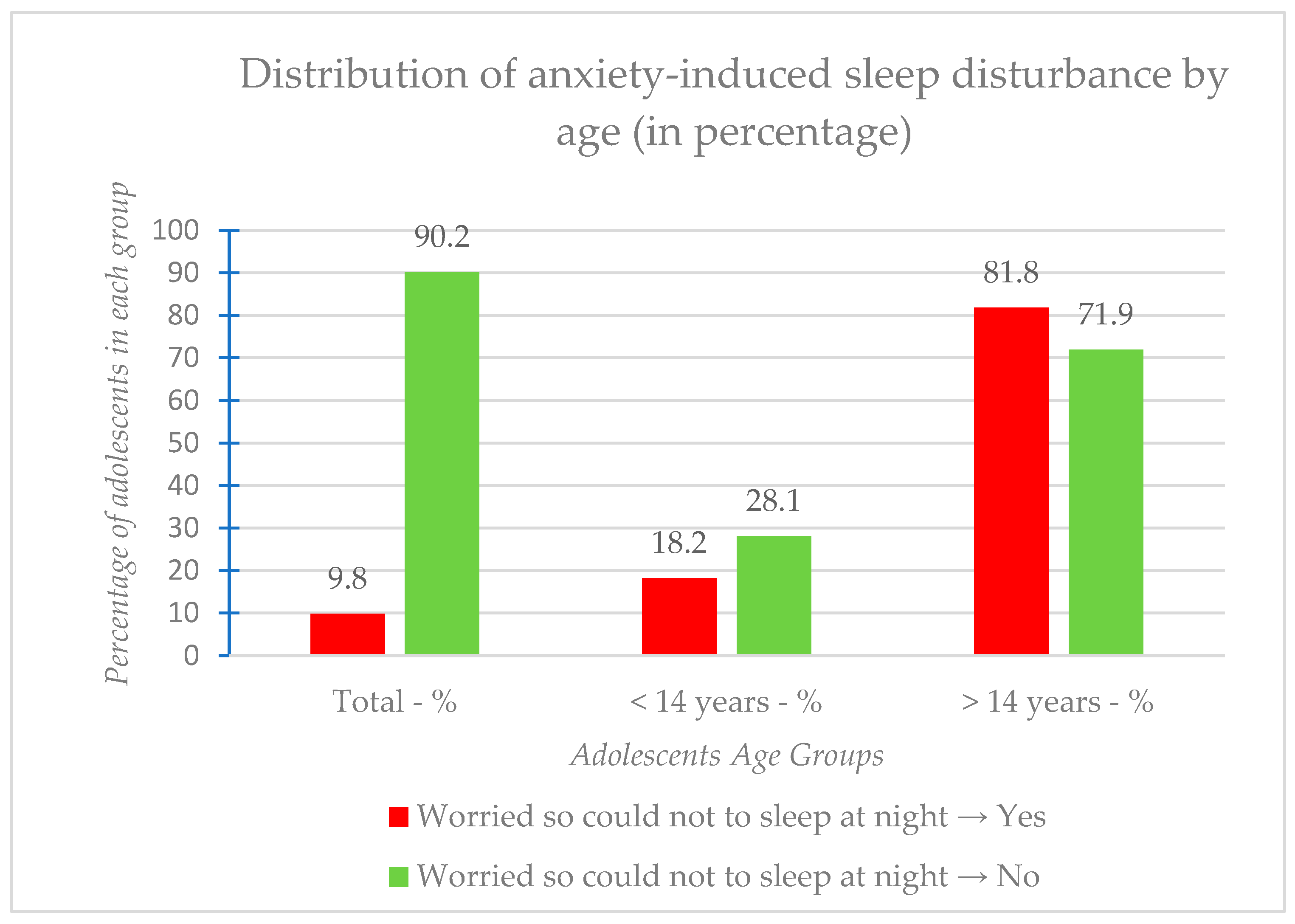

- Well-being and Health: This category encompassed questions designed to assess adolescents’ general health perceptions, nutritional status (derived from self-reported height and weight), and sleep patterns, including anxiety-induced sleep disturbance, which is a key mental health indicator.

- Social Connections: Questions in this section evaluated various aspects of adolescents’ social support networks, including the presence of close friends, experiences of loneliness, perceived peer support within the school environment, and the availability of emotional support.

- Parental Bonding Relations: This domain focused on the quality of adolescents’ relationships with their parents or guardians, assessing perceived parental understanding (connectedness), supervision, and active checking-in on their activities.

- Bullying: This category included questions on both traditional bullying experienced on school property and cyberbullying via social networks, along with inquiries about the source and reasons behind bullying incidents.

- Safety and Protection Factors: This section assessed health-protective behaviors such as seatbelt and helmet use, as well as specific practices related to the COVID-19 pandemic, including mask-wearing, experience with distance learning, and COVID-19 testing or vaccination history.

- Social Behaviors—Use of Social Networks: This category included questions on daily screen time and specific usage patterns of social networks, along with parental rules regarding screen time and mobile phone ownership.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Group

3.2. Health Perceptions and Well-Being

3.3. Social Connections and Peer Support

3.4. Parental Bonding Relations

3.5. Bullying

3.6. Safety and Protection Factors

3.7. Factors Associated with Anxiety-Induced Sleep Disturbance

3.8. Exploring the Relation Between Bullying and Contributing Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| GSHS | Global School-Based Student Health Survey |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease-19 |

| SNS | Social Networking Site |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| UNAIDS | Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| UNICEF | United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund |

References

- World Health Organisation. Coming of Age: Adolescent Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/coming-of-age-adolescent-health (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- World Health Organisation. Fact Sheets. Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Adolescents. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Sung, J.M.; Kim, Y.J. Sex Differences in Adolescent Mental Health Profiles in South Korea. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2020, 34, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarfo, J.O.; Gbordzoe, N.I.; Commey, V.D.; Tawiah, E.D.-Y.; Hagan, J.E. Gender Differences in Anxiety-Induced Sleep Disturbance: A Survey Among In-School Adolescents in the Republic of Benin. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Lu, S.; Duan, Z.; Wilson, A.; Jia, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, R. Associations between Sex Differences, Eating Disorder Behaviors, Physical and Mental Health, and Self-Harm among Chinese Adolescents. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galán-Arroyo, C.; Gómez-Paniagua, S.; Contreras-Barraza, N.; Adsuar, J.C.; Olivares, P.R.; Rojo-Ramos, J. Bullying and Self-Concept, Factors Affecting the Mental Health of School Adolescents. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaskulska, S.; Jankowiak, B.; Pérez-Martínez, V.; Pyżalski, J.; Sanz-Barbero, B.; Bowes, N.; Claire, K.D.; Neves, S.; Topa, J.; Silva, E.; et al. Bullying and Cyberbullying Victimization and Associated Factors among Adolescents in Six European Countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, M.; Burbidge, V.; El Asam, A.; Foody, M.; Smith, P.K.; Morsi, H. Bullying and Cyberbullying: Their Legal Status and Use in Psychological Assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichel, R.; Foody, M.; O’Higgins Norman, J.; Feijóo, S.; Varela, J.; Rial, A. Bullying, Cyberbullying and the Overlap: What Does Age Have to Do with It? Sustainability 2021, 13, 8527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Public Health. National-Report-on-Health-of-Children-and-Youths-in-Romania-2020.Pdf. Available online: https://insp.gov.ro/download/cnepss/stare-de-sanatate/rapoarte_si_studii_despre_starea_de_sanatate/sanatatea_copiilor/rapoarte-nationale/Raport-National-de-Sanatate-a-Copiilor-si-Tinerilor-din-Romania-2020.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025). (In Romanian)

- Ciucă, A.; Baban, A. Youth Mental Health Context in Romania. Eur. Health Psychol. 2016, 3, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Copaceanu, M.; Costache, I. Child and Adolescent Mental Health in Romania—A Snapshot; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/romania/media/10916/file/Child%20and%20Adolescent%20Mental%20Health%20in%20Romania%20(A%20Snapshot).pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Copaceanu, M. Sex, Alcohol, Marijuana and Depression Among Young People in Romania. National Study with the Participation of over 10,000 Young People and 1200 Parents; Editura Universitara: Bucuresti, Romania, 2020; ISBN 978-606-28-1157-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sârbu, E.A.; Iovu, M.-B.; Lazăr, F. Negative Life Events and Internalizing Problems among Romanian Youth. Clin. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, M.; Papari, A.; Seceleanu, A.; Sunda, I. Suicide in Romania Compared to the Eu-28 Countries. Soc. Sci. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 6, 131–148. [Google Scholar]

- The National Strategy for the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents 2016–2020. Available online: https://gov.ro/ro/stiri/strategie-nationala-pentru-sanatatea-mintala-a-copilului-i-adolescentului-2016-2020-orientata-spre-preventie-i-sprijin-personalizat (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Help Autism Association: Lack of Integrated Specialized Services, One of the Main Problems Facing Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Available online: https://rohealthreview.ro/asociatia-help-autism-lipsa-serviciilor-specializate-integrate-una-dintre-principalele-probleme-cu-care-se-confrunta-pacientii-cu-tulburari-de-spectru-autist/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- National Institute of Public Health. Mental Health. Situation Analysis 2021. Available online: https://insp.gov.ro/download/cnepss/stare-de-sanatate/boli_netransmisibile/sanatate_mintala/Analiza-de-Situatie-2021.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025). (In Romanian)

- Popescu, C.A.; Tegzeșiu, A.M.; Suciu, S.M.; Covaliu, B.F.; Armean, S.M.; Uță, T.A.; Sîrbu, A.C. Evolving Mental Health Dynamics among Medical Students amid COVID-19: A Comparative Analysis of Stress, Depression, and Alcohol Use among Medical Students. Medicina 2023, 59, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumitrache, L.; Stănculescu, E.; Nae, M.; Dumbrăveanu, D.; Simion, G.; Taloș, A.M.; Mareci, A. Post-Lockdown Effects on Students’ Mental Health in Romania: Perceived Stress, Missing Daily Social Interactions, and Boredom Proneness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop, L.M.; Iorga, M.; Iurcov, R. Body-Esteem, Self-Esteem and Loneliness among Social Media Young Users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovu, M.-B.; Runcan, R.; Runcan, P.-L.; Andrioni, F. Association between Facebook Use, Depression and Family Satisfaction: A Cross-Sectional Study of Romanian Youth. Iran. J. Public Health 2020, 49, 2111–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftei, A.; Opariuc-Dan, C. Perfect People, Happier Lives? When the Quest for Perfection Compromises Happiness: The Roles Played by Substance Use and Internet Addiction. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1234164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drosopoulou, G.; Vlasopoulou, F.; Panagouli, E.; Stavridou, A.; Papageorgiou, A.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Tsolia, M.; Tzavara, C.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Tsitsika, A.K. Cross-National Comparisons of Internalizing Problems in a Cohort of 8952 Adolescents from Five European Countries: The EU NET ADB Survey. Children 2022, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global School-Based Student Health Survey. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/global-school-based-student-health-survey (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Roșioară, A.-I.; Năsui, B.A.; Ciuciuc, N.; Sîrbu, D.M.; Curșeu, D.; Vesa, Ș.C.; Popescu, C.A.; Bleza, A.; Popa, M. Beyond BMI: Exploring Adolescent Lifestyle and Health Behaviours in Transylvania, Romania. Nutrients 2025, 17, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF Romania. Country Program for UNICEF in Romania 2023–2027; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/romania/media/12906/file/UNICEF%20Romania%20Country%20Programme%202023-2027.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- AGERPRES The School Population in the National Education System Was 3.47 Million Pupils and Students in the Year 2022/2023. Available online: http://www.agerpres.ro/economic/2023/06/20/populatia-scolara-din-sistemul-national-de-educatie-a-fost-de-3-47-milioane-de-elevi-si-studenti-in-anul-2022-2023--1126750 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Ministry of Education. Report Regarding the Condition of the Preuniversity Education from Romania 2022–2023. Available online: https://www.edu.ro/sites/default/files/_fi%C8%99iere/Minister/2023/Transparenta/Rapoarte_sistem/Raport-Starea-invatamantului-preuniversitar-2022-2023.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- World Health Organisation. Growth Reference 5–19 Years—BMI-for-Age (5–19 Years). Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years/indicators/bmi-for-age (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Eurostat. Statistics Explained. Self-Perceived Health Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Self-perceived_health_statistics (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Stock, C.; Mikolajczyk, R.; Bilir, N.; Petkeviciene, J.; Naydenova, V.; Dudziak, U.; Marin-Fernandez, B.; El Ansari, W. Gender Differences in Students’ Health Complaints: A Survey in Seven Countries. J. Public Health 2007, 16, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, C.P.; Asnaani, A.; Litz, B.T.; Hofmann, S.G. Gender Differences in Anxiety Disorders: Prevalence, Course of Illness, Comorbidity and Burden of Illness. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 45, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, C.; Deyra, M.; Berland, P.; Gerbaud, L.; Pizon, F. Girl–Boy Differences in Perceptions of Health Determinants and Cancer: A More Systemic View of Girls as Young as 6 Years. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1296949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, Y.; Doi, S.A.R.; Najman, J.M.; Mamun, A.A. Exploring Gender Difference in Sleep Quality of Young Adults: Findings from a Large Population Study. Clin. Med. Res. 2016, 14, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchflower, D.; Bryson, A. The Gender Well-Being Gap. Soc. Indic. Res. 2024, 173, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, T.; Iannotti, R.J.; Simons-Morton, B.G. Overweight, Obesity, Youth, and Health-Risk Behaviors. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 38, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelemy, J.; Coakley, T.M.; Washington, T.; Joseph, A.; Eugene, D.R. Examination of Risky Truancy Behaviors and Gender Differences among Elementary School Children. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2022, 32, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srem-Sai, M.; Agormedah, E.K.; Hagan, J.E.; Gbordzoe, N.I.; Sarfo, J.O. Gender-Based Biopsychosocial Correlates of Truancy in Physical Education: A National Survey among Adolescents in Benin. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbels, J.; Van Der Put, C.E.; Assink, M. Risk Factors for School Absenteeism and Dropout: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Services Department of Health & Human. Victoria State Departament. Services. Teenagers and Sleep. Available online: http://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/healthyliving/teenagers-and-sleep (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Teens and Sleep. Available online: https://www.sleepfoundation.org/teens-and-sleep (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Rose, A.J.; Rudolph, K.D. A Review of Sex Differences in Peer Relationship Processes: Potential Trade-Offs for the Emotional and Behavioral Development of Girls and Boys. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 98–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, T.M.; Aldao, A. Gender Differences in Emotion Expression in Children: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 735–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablotsky, B.; Ng, A.E.; Black, L.I.; Bose, J.; Jones, J.R.; Maitland, A.K.; Blumberg, S.J. Perceived Social and Emotional Support Among Teenagers: United States, July 2021–December 2022. In National Health Statistics Reports [Internet]; National Center for Health Statistics (US): Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Roșioară, A.-I.; Năsui, B.A.; Ciuciuc, N.; Sîrbu, D.M.; Curșeu, D.; Pop, A.L.; Popescu, C.A.; Popa, M. Status of Healthy Choices, Attitudes and Health Education of Children and Young People in Romania—A Literature Review. Medicina 2024, 60, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, H.; Elliott, L.; Kennedy, C.; Hanley, J. Parent–Child Connectedness and Communication in Relation to Alcohol, Tobacco and Drug Use in Adolescence: An Integrative Review of the Literature. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2017, 24, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobak, R.; Abbott, C.; Zisk, A.; Bounoua, N. Adapting to the Changing Needs of Adolescents: Parenting Practices and Challenges to Sensitive Attunement. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 15, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravender, T. Adolescents and the Importance of Parental Supervision. Pediatrics 2015, 136, 761–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Song, G.; Liu, Q.; Tang, X. The Relationship Between Parent-Adolescent Communication and Depressive Symptoms: The Roles of School Life Experience, Learning Difficulties and Confidence in the Future. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 1295–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.S.; Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Danaei, G.; Shibuya, K.; Adair-Rohani, H.; AlMazroa, M.A.; Amann, M.; Anderson, H.R.; Andrews, K.G.; et al. A Comparative Risk Assessment of Burden of Disease and Injury Attributable to 67 Risk Factors and Risk Factor Clusters in 21 Regions, 1990–2010: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2224–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Questions | Coding Schemes |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic | ||

| Age [27] | How old are you? | 11 or younger, 12–14 “≤14” 15–18 or older “≥15” [27] |

| Sex | What is your sex? | Female “Girls”; Male “Boys” [27] |

| Background | What residential area do you live in? | “Rural”; “Urban” |

| Well-being and Health | ||

| Nutritional status (calculated using BMI WHO Z-score cut-off [31]) | “How tall are you without shoes?“ [26] “What is your weight?” [26] | <−2 SD from median for BMI by age and sex “Underweight” >+1 SD from median for BMI by age and sex “Overweight” >+2 SD from median for BMI by age and sex “Obese” [31] |

| Self-perceived health status | “How would you describe your health in general?” [26] | Excellent/very good/good “Positive Perception About Health” [27] Acceptable/poor “Negative Perception About Health” |

| Worries and sleep anxiety | “In the past 6 months, how often were you so worried about something that you couldn’t sleep at night?” [26] | Most of the time/always “Yes” Never/rarely/sometimes “No” |

| Sleeping hours per night | “During school time, how many hours do you sleep each night?” [26] | <8 h per night “Not Enough Sleep” ≥8 h per night “Enough Sleep” |

| Social connections | ||

| Having friends | “How many close friends do you have?”(friends you can confine to, you feel safe with) [26] | 0 friends “ No—not having fiends” 1 friend/2 friends/3 or more friends “Yes—having friends” |

| Loneliness | “In the past 6 months, how often have you felt lonely?” [26] | Most of the time/always “Yes” Never/rarely/sometimes “No” |

| School truancy | “In the past 30 days, how many days were you absent from school without permission? (i.e., you skipped school)” [26] | 3 to 5 days/6 to 9 days/10 or more days “Yes” 0 days/1 or 2 days “No” |

| Kind and helpful colleague/peer support | “In the past 30 days, how often has it happened that most of the students in your school were kind and helpful?” [26] | Most of the time/always “Yes” Never/rarely/sometimes “No” |

| Emotional support | “In the past 30 days, how often were you able to talk to someone about your problems and worries?” [26] | Most of the time/always “Yes” Never/rarely/sometimes “No” |

| Parental bonding relations | ||

| Parental or guardian connectedness | “In the past 30 days, how often did your parents or guardians understand your problems and worries?” [26] | Most of the time/always “Yes” Never/rarely/sometimes “No” |

| Parental or guardian supervision | “In the past 30 days, how often did your parents or guardians check on you to see if you did your homework?” [26] | Most of the time/always “Yes” Never/rarely/sometimes “No” |

| Parental or guardian check | “In the past 30 days, how often did your parents or guardians really know what you were doing in your free time?” [26] | Most of the time/always “Yes” Never/rarely/sometimes “No” |

| Bullying | ||

| Bullying experience | “In the past 12 months, have you been bullied or harassed on school property (by other children or classmates)?” [26] | “Yes” “No” |

| Cyberbullying experience | “In the past 12 months, have you been cyberbullied (on social networks)?” [26] | “Yes” “No” |

| Source of Bullying | “In the past 12 months, who bullied you most often?” [26] | No one “No” Students in my school/students from another school/another person my age “Yes” |

| Reason of Bullying | “In the past 12 months, what was the main reason you were bullied?” [26] | I have not been harassed in the past 12 months “No” Because of the way my body or face looks/because of my disabilities/because of my ethnicity or skin color “Physical and Ethnicity reasons” Because of my gender, sexual orientation, or gender identity “Sexual orientation and gender identity” Because of my religion/because I was good at school “Religion and personal beliefs” Because of how rich or poor my family is “Family income or social status reasons” Other reasons “Others” |

| Safety and Protection Factors | ||

| Seat belt | “In the past 30 days, how often did you wear a seat belt when you were in a car or other motorized vehicle driven by someone else?” [26] | Most of the time/always “Yes” Never/rarely/sometimes “No” |

| Helmet | “In the last 30 days, how often did you wear a helmet when riding a bicycle?” [26] | Most of the time/always “Yes” I haven’t ridden a bike in the last 30 days/never/rarely/sometimes “No” |

| COVID-19 Mask | “During the COVID-19 pandemic, how often did you wear a mask or other face covering to protect yourself or others from the disease when in public?” [26] | Most of the time/always “Yes” Never/rarely/sometimes “No” |

| Home-Schooling with technology (during COVID-19) | “During the COVID-19 pandemic, did you attend school from home at least part of the time using a computer, cell phone, or other electronic devices?” [26] | “Yes” “No” |

| Testing COVID-19 history | “During the COVID-19 pandemic, were you tested by a doctor or nurse for COVID-19 infection?” [26] | “Yes” “No” “I don’t know” |

| COVID-19 vaccination | “Have you been vaccinated to prevent infection with COVID-19?” [26] | “Yes” “No” “I don’t know” |

| Social behaviors—the use of social networks | ||

| Screen time (hours/day) | “On a typical school day, how many hours of screen time do you spend?” [26] | </= than 2 h/day: “No risk factor” > than 2 h/day: “Risk factor” |

| Use of social network | “In the past 7 days, how many hours a day did you use your mobile phone for social networks, for online communication or to surf the Internet?” [26] | </= than 2 h/day: “No risk factor” > than 2 h/day: “ Risk factor” |

| Parental rules for screen time and social network | “Do your parents or guardians have rules about how you can use social media, online communication or the Internet?” [26] | “Yes” “No” |

| Having a personal mobile phone | “Do you have your own mobile phone to use?” [26] | “Yes” “No” |

| Variables | Category | N = 900 | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Girls | 474 | 52.7 |

| Boys | 426 | 47.3 | |

| Age | Under 14 | 244 | 27.1 |

| Over 14 | 656 | 72.9 | |

| Class | 5–8 (gymnasium) | 247 | 27.4 |

| 9–12 (high school) | 653 | 72.6 | |

| Residence | Urban | 639 | 71 |

| Rural | 261 | 29 |

| Variable | Item | Total, n (%) | Girls, n (%) | Boys, n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-Being and Health | |||||

| Perceived health status [27] | Negative perception | 122 (13.6) | 89 (18.8) | 33 (7.7) | <0.001 * |

| Positive perception | 778 (86.4) | 385 (81.2) | 393 (92.3) | ||

| Nutritional status [27] | Underweight, normal weight | 685 (76.1) | 396 (−83.5) | 289 (−67.8) | <0.001 * |

| overweight, obese | 215 (23.9) | 78 (−16.5) | 137 (−32.2) | ||

| Sleep hours per night | <8 | 532 (59.1) | 292 (61.6) | 240 (56.3) | 0.118 |

| ≥8 | 368 (40.9) | 182 (38.4) | 186 (43.7) | ||

| Worries and sleep anxiety | No | 812 (90.2) | 407 (85.9) | 405 (95.1) | <0.001 * |

| Yes | 88 (9.8) | 67 (14.1) | 21 (4.9) | ||

| Variable | Item | Total, n (%) | Girls, n (%) | Boys, n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Connections | |||||

| Having friends | No | 29 (3.2) | 10 (2.1) | 19 (4.5) | 0.071 |

| Yes | 871 (96.8) | 464 (97.7) | 407 (95.5) | ||

| Loneliness | No | 769 (85.4) | 391 (82.5) | 378 (88.7) | 0.011 * |

| Yes | 131 (14.6) | 83 (17.5) | 48 (11.3) | ||

| School truancy | No | 844 (93.8) | 453 (95.6) | 391 (91.8) | 0.027 * |

| Yes | 56 (6.2) | 21 (4.4) | 35 (8.2) | ||

| Kind and helpful colleagues/peer support | No | 512 (56.9) | 288 (60.8) | 224 (52.6) | 0.016 * |

| Yes | 388 (43.1) | 186 (39.2) | 202 (47.4) | ||

| Emotional support | No | 528 (58.6) | 265 (55.9) | 263 (61.7) | 0.076 |

| Yes | 372 (41.3) | 209 (44.1) | 163 (38.3) | ||

| Variable | Item | Total, n (%) | Girls, n (%) | Boys, n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Bonding Relations | |||||

| Parental or guardian connectedness | No | 340 (37.8) | 192 (40.5) | 148 (34.7) | 0.043 * |

| Yes | 560 (62.2) | 282 (59.5) | 278 (65.3) | ||

| Parental or guardian supervision | No | 665 (73.9) | 365 (77) | 300 (70.4) | 0.03 * |

| Yes | 235 (26.1) | 109 (23) | 126 (29.6) | ||

| Parental or guardian check | No | 206 (22.9) | 110 (23.2) | 96 (22.5) | 0.873 |

| Yes | 694 (77.1) | 364 (76.8) | 330 (77.5) | ||

| Variable | Item | Total, n (%) | Girls, n (%) | Boys, n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bullying | |||||

| Bullying experience (ever) | No | 806 (89.6) | 432 (91.1) | 374 (87.8) | 0.063 |

| Yes | 94 (10.4) | 42 (8.9) | 52 (12.2) | ||

| Cyberbullying experience | No | 823 (91.4) | 437 (92.2) | 386 (90.6) | 0.233 |

| Yes | 77 (8.6) | 37 (7.8) | 40 (9.4) | ||

| Source of bullying (last 12 months) | No bullying | 461 (51.2) | 245 (51.7) | 216 (50.7) | 0.41 |

| Yes (colleagues, mates) | 439 (48.8) | 229 (48.3) | 210 (49.3) | ||

| Reason of bullying | No bullying | 696 (77.3) | 359 (75.7) | 337 (79.1) | 0.22 |

| Physical and ethnicity reasons | 98 (10.9) | 61 (12.9) | 37 (8.7) | ||

| Religion and personal beliefs | 18 (2.0) | 11 (2.3) | 7 (1.6) | ||

| Sexual orientation and gender identity | 13 (1.4) | 7 (1.5) | 6 (1.4) | ||

| Family income or social status reasons | 8 (0.9) | 2 (0.4) | 6 (1.4) | ||

| Other reasons | 67 (7.4) | 34 (7.2) | 33 (7.7) | ||

| Safety and Protection Factors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seat belt | No | 188 (20.9) | 96 (20.3) | 92 (21.6) | 0.68 |

| Yes | 712 (79.1) | 378 (79.7) | 334 (78.4) | ||

| Helmet (during bicycling) | No | 844 (93.8) | 453 (95.6) | 391 (91.8) | 0.027 * |

| Yes | 56 (6.2) | 21 (4.4) | 35 (8.2) | ||

| COVID-19 mask | No | 122 (13.6) | 41 (8.6) | 81 (19) | <0.001 * |

| Yes | 778 (86.9) | 433 (91.4) | 345 (81) | ||

| Home-schooling with technology (during COVID-19) | No | 13 (1.4) | 7 (1.5) | 6 (1.4) | 1 |

| Yes | 887 (98.6) | 467 (98.5) | 420 (98.6) | ||

| COVID-19 testing history | No | 295 (32.8) | 153 (17) | 142 (15.8) | 0.08 |

| Yes | 538 (59.8) | 277 (30.8) | 261 (29) | ||

| I don’t know | 67 (7.4) | 44 (4.9) | 23 (2.6) | ||

| COVID-19 vaccination | No | 654 (72.7) | 346 (38.4) | 308 (34.2) | 0.955 |

| Yes | 226 (25.1) | 118 (13.1) | 108 (12) | ||

| I don’t know | 20 (2.2) | 10 (1.1) | 10 (1.1) | ||

| Model | B | p | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | ||||

| Sex (male) | −1.109 | <0.001 * | 0.33 | 0.191 | 0.572 |

| Bullying (yes) | 0.27 | 0.475 | 1.31 | 0.625 | 2.745 |

| Cyberbullying (yes) | 0.654 | 0.085 | 1.924 | 0.913 | 4.054 |

| Loneliness (yes) | 1.368 | <0.001 * | 3.928 | 2.334 | 6.612 |

| Emotional support (yes) | −0.872 | 0.011 * | 0.418 | 0.213 | 0.819 |

| Parental or guardian connectedness (yes) | −0.743 | 0.008 * | 0.476 | 0.274 | 0.825 |

| Peer support (yes) | −0.345 | 0.208 | 0.708 | 0.414 | 1.212 |

| Sleep hours per night (yes) | −0.911 | 0.004 * | 0.402 | 0.218 | 0.742 |

| Constant | −2.153 | <0.001 | 0.116 | ||

| Model | B | p | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | ||||

| Cyberbullying (yes) | 1.927 | <0.001 * | 6.868 | 3.445 | 13.692 |

| Friends (yes) | −0.714 | 0.098 | 0.49 | 0.21 | 1.14 |

| Talking about problems with someone (yes) | −0.171 | 0.264 | 0.843 | 0.625 | 1.138 |

| Talking about problems with parents (yes) | −0.296 | 0.064 | 0.744 | 0.544 | 1.017 |

| Loneliness (yes) | 0.776 | <0.001 * | 2.173 | 1.413 | 3.342 |

| Peer support (yes) | −0.168 | 0.243 | 0.846 | 0.638 | 1.121 |

| Sleep hours per night (yes) | −0.26 | 0.076 | 0.771 | 0.578 | 1.028 |

| Constant | 1.744 | <0.001 | 5.719 | ||

| Model | B | p | OR | 95% CI for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | ||||

| Age | −0.725 | 0.004 * | 0.484 | 0.295 | 0.794 |

| Cyberbullying (yes) | 2.03 | <0.001 * | 7.615 | 4.397 | 13.186 |

| Loneliness (yes) | 0.483 | 0.096 | 1.621 | 0.917 | 2.864 |

| Social networks (yes) | −0.456 | 0.071 | 0.634 | 0.387 | 1.039 |

| Peer support (yes) | −0.813 | 0.002 * | 0.443 | 0.266 | 0.739 |

| Constant | 0.058 | 0.892 | 1.059 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roșioară, A.-I.; Năsui, B.A.; Ciuciuc, N.; Sîrbu, D.M.; Curșeu, D.; Vesa, Ș.C.; Popescu, C.A.; Popa, M. Beyond the Classroom: The Role of Social Connections and Family in Adolescent Mental Health in the Transylvanian Population of Romania. Medicina 2025, 61, 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61061031

Roșioară A-I, Năsui BA, Ciuciuc N, Sîrbu DM, Curșeu D, Vesa ȘC, Popescu CA, Popa M. Beyond the Classroom: The Role of Social Connections and Family in Adolescent Mental Health in the Transylvanian Population of Romania. Medicina. 2025; 61(6):1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61061031

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoșioară, Alexandra-Ioana, Bogdana Adriana Năsui, Nina Ciuciuc, Dana Manuela Sîrbu, Daniela Curșeu, Ștefan Cristian Vesa, Codruța Alina Popescu, and Monica Popa. 2025. "Beyond the Classroom: The Role of Social Connections and Family in Adolescent Mental Health in the Transylvanian Population of Romania" Medicina 61, no. 6: 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61061031

APA StyleRoșioară, A.-I., Năsui, B. A., Ciuciuc, N., Sîrbu, D. M., Curșeu, D., Vesa, Ș. C., Popescu, C. A., & Popa, M. (2025). Beyond the Classroom: The Role of Social Connections and Family in Adolescent Mental Health in the Transylvanian Population of Romania. Medicina, 61(6), 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61061031