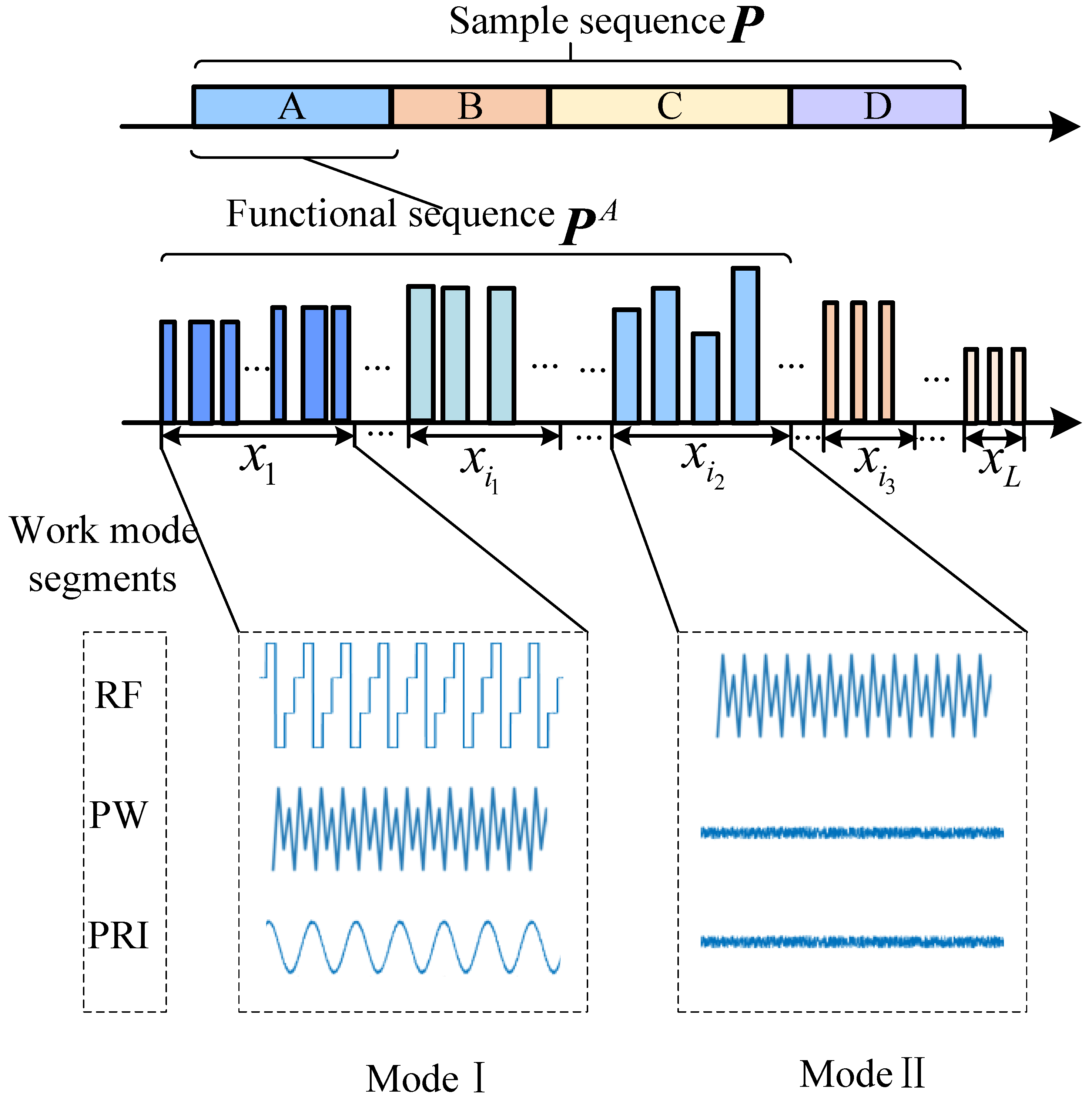

This paper proposes TriSCL (Triple-branch Semi-supervised Contrastive Learning), an end-to-end framework for fine-grained radar work mode recognition under non-ideal conditions using limited labeled samples. As shown in

Figure 3, the TriSCL model accepts a semi-labeled dataset consisting of unlabeled and labeled samples. Leveraging the signal characteristics of missing and false pulses, we designed two data enhancement functions. Using these functions for augmentation on unlabeled data produces three distinct views: a tail mask view, a timestamp mask view, and a strongly augmented view (combining both techniques). These views are mapped to an embedding space by encoder

f, where the tail mask view and timestamp mask view try to compute the unsupervised comparison loss by instance with the strongly augmented view, respectively. Meanwhile, the labeled samples go through the encoder to compute the supervised contrast loss in the same embedding space, and then through the classifier to compute the classification loss.

4.1. Data Augmentation

To enhance the robustness and generalization capability of radar work mode recognition models under non-ideal conditions, we design two data augmentation techniques for unlabeled samples to simulate pulse loss and false pulse scenarios.

Pulse loss refers to the phenomenon where portions of radar pulses are missing due to noise, interference, or hardware failures. To emulate this condition, we employ a tail masking strategy where the three parameters of the PDW are masked in the posterior part of a sample by a certain percentage. For the input data

, where

B is the batch size,

T is the number of pulses in a sample, and

C is the feature dimension (i.e., the three parameters of the PDW). We calculate the number of pulses to be masked:

, where

r is the masking ratio. The masked data

is generated by zeroing the last

L pulses across all PDW parameters:

False pulses are a non-authentic radar pulse signal that is generated in radar signal processing due to various interferences, noises, or spoofing techniques. To simulate this phenomenon, we adopt a timestamp masking strategy, randomly masking a portion of pulses in a sample pulse train. Specifically, a Bernoulli-distributed mask matrix

is generated, where each element takes the value 1 (indicating masking) with probability

p, and 0 (indicating retention) with probability

. This mask matrix is then applied to the input data

X to obtain the masked data

.

Figure 4 demonstrates the data before and after applying two data augmentation strategies, using the PRI parameter as an example. Through the two strategies for data augmentation, the model significantly enhances its capability to extract discriminative features, improves adaptability to complex signal conditions, and achieves higher recognition accuracy under pulse distortion scenarios.

4.3. Hybrid Loss

For a batch of unlabeled samples

with batch size

N:

, two augmented versions are generated for each sample through distinct data augmentation operations:

and

These augmented samples

and

will be fed into the feature extraction network and projection network to obtain their embedded representations:

and

where

,

M denotes the feature dimension. The batch dimensions of

and

are connected to form

.

Z is used to compute the following contrastive loss function:

Assuming the positive sample feature index for

is

k, the loss function to calculate the similarity between the embedding feature of positive and negative samples is denoted as:

where

is the cosine similarity between the features of the

ith and the

jth sample,

is the temperature coefficient, and

is the cosine similarity between the features of the

ith sample and the features of its positive sample.

The loss function, formulated as a combination of the negative logarithm and SoftMax, drives the inner term towards 1. This property can effectively improve the similarity measure between positive sample pairs while reducing the similarity among negative pairs. Given the bounded range of pairwise similarity, the optimization objective of minimizing the loss function can only be reached when the feature distance between positive samples is reduced, and the separation between negative samples is increased simultaneously.

Within the contrast learning framework, the temperature coefficient is mainly used to control the degree of influence of positive and negative sample pairs in the model training process. Taking negative sample pairs as an example, in the high-dimensional feature space, there are significant differences in the similarity performance between different negative sample pairs, with some negative sample pairs presenting higher similarity and others lower similarity. In this case, a smaller temperature coefficient will make the loss function pay more attention to the pairs of negative samples with high similarity. On the contrary, a larger temperature coefficient will help to mitigate over-emphasis on these similar samples, which, in turn, effectively reduces overfitting risks and improves the model’s generalization ability and robustness.

This paper adopts an end-to-end semi-supervised learning framework. Compared with the two-stage contrastive learning method, the proposed method allows the contrastive loss in unsupervised training to directly fine-tune the downstream classifier. At the same time, it can also make full use of the classification loss of labeled data to achieve the unification of model training and optimization, and improve the recognition accuracy for specific tasks [

33].

For each unlabeled data

, we first employ specialized data augmentation techniques to generate two augmented views and one strongly augmented view that combines both augmentation strategies. The first augmentation applies tail masking with a 30% truncation ratio, processed through encoder

f to obtain embedding

, while the second employs timestamp masking via binomial sampling (

p = 0.2) to produce embedding

. The strongly augmented view, combining both augmentation strategies, generates a reference embedding

through the same encoder. Within the contrastive learning framework, embeddings derived from different views of the same sample form positive pairs, while those from different samples constitute negative pairs. We optimize the model using normalized temperature-scaled cross-entropy loss [

29] to minimize distances between positive samples and increase the distance between negative samples. The unsupervised loss

is computed between embeddings

and

, while

is derived from

and

. This dual loss enforces feature consistency across different distortion patterns.

where

denotes the similarity function, as defined in Equation (

16).

For semi-supervised radar work mode recognition tasks, labeled and unlabeled data may originate from the same dataset with identical distributions. For labeled samples, the shared encoder

f generates embeddings

that reside in the same latent space as

,

, and

from unlabeled data. The supervised contrastive loss

is computed by treating embeddings from the same class as positive pairs and those from different classes as negative pairs. This objective simultaneously maximizes intra-class similarity and minimizes inter-class similarity of the embeddings. For a labeled PDW sample

with ground-truth class

y, its embedding

is obtained through encoder

f, and the supervised contrastive loss is formulated as:

where

denotes the embedding of samples belonging to the same class as

, i.e.,

, while

represents embeddings from different classes, i.e.,

. The optimization of the supervised contrastive loss drives the model to produce more tightly clustered embeddings for intra-class samples while maximizing separation for inter-class instances, ultimately yielding discriminative feature representations that are particularly effective for classification objectives. Subsequently, the labeled sample’s embedding

is fed into classifier

g to predict the label

. The standard softmax cross-entropy loss

is then computed between

and the ground-truth label

y to optimize the model for radar work mode classification. The classifier comprises a single FC layer with an input dimension of 128 (matching the embedding space) and an output dimension of 6 (corresponding to the number of work mode categories), optimized using cross-entropy loss as the classification objective.

where

represents the predicted probability for class

c given a labeled sample, while

denotes the indicator function that equals 1 when the true label of the

ith labeled sample is

c, and 0 otherwise. In terms of the loss function, the unsupervised contrastive loss learns representations by maximizing the consistency between different augmented views of the same sample. Supervised contrastive learning utilizes the supervised contrastive loss to reduce the distance between samples of the same class in the embedding space. To jointly train this end-to-end framework, the final loss function is a hybrid loss that combines weighted contributions from the unsupervised contrastive loss, supervised contrastive loss, and classification loss.

where

and

denote the unsupervised contrastive losses,

represents the supervised contrastive loss, and

is the classification loss. The hyperparameters

,

,

, and

are introduced to balance the contributions of these four loss terms.

During training, the model updates the encoder f and classifier g by minimizing the hybrid loss, allowing it to learn effective representations from both labeled and unlabeled data while directly optimizing predicted class probabilities to enhance classification performance.