An Improved Lightweight Model for Protected Wildlife Detection in Camera Trap Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We construct a dataset of protected wildlife from camera traps, encompassing diverse scenarios, varying object scales, and complex backgrounds. This dataset addresses the scarcity of specialized data and provides a valuable resource for ecological monitoring research.

- We propose YOLO11-APS, an enhanced lightweight model built on YOLO11n. By integrating efficient components such as ACmix, PConv, and SlimNeck, our model achieves an optimal balance between accuracy and computational efficiency, improving feature representation and inference speed to facilitate deployment on ecological monitoring resource-constrained devices.

- Experimental results demonstrate that YOLO11-APS outperforms mainstream object detection models in both accuracy and efficiency on protected wildlife data, underscoring its potential as a deployable solution for intelligent, real-time monitoring in conservation areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition

2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.3. Overview of Baseline Model

2.4. Proposed Model

2.4.1. Self-Attention and Convolution

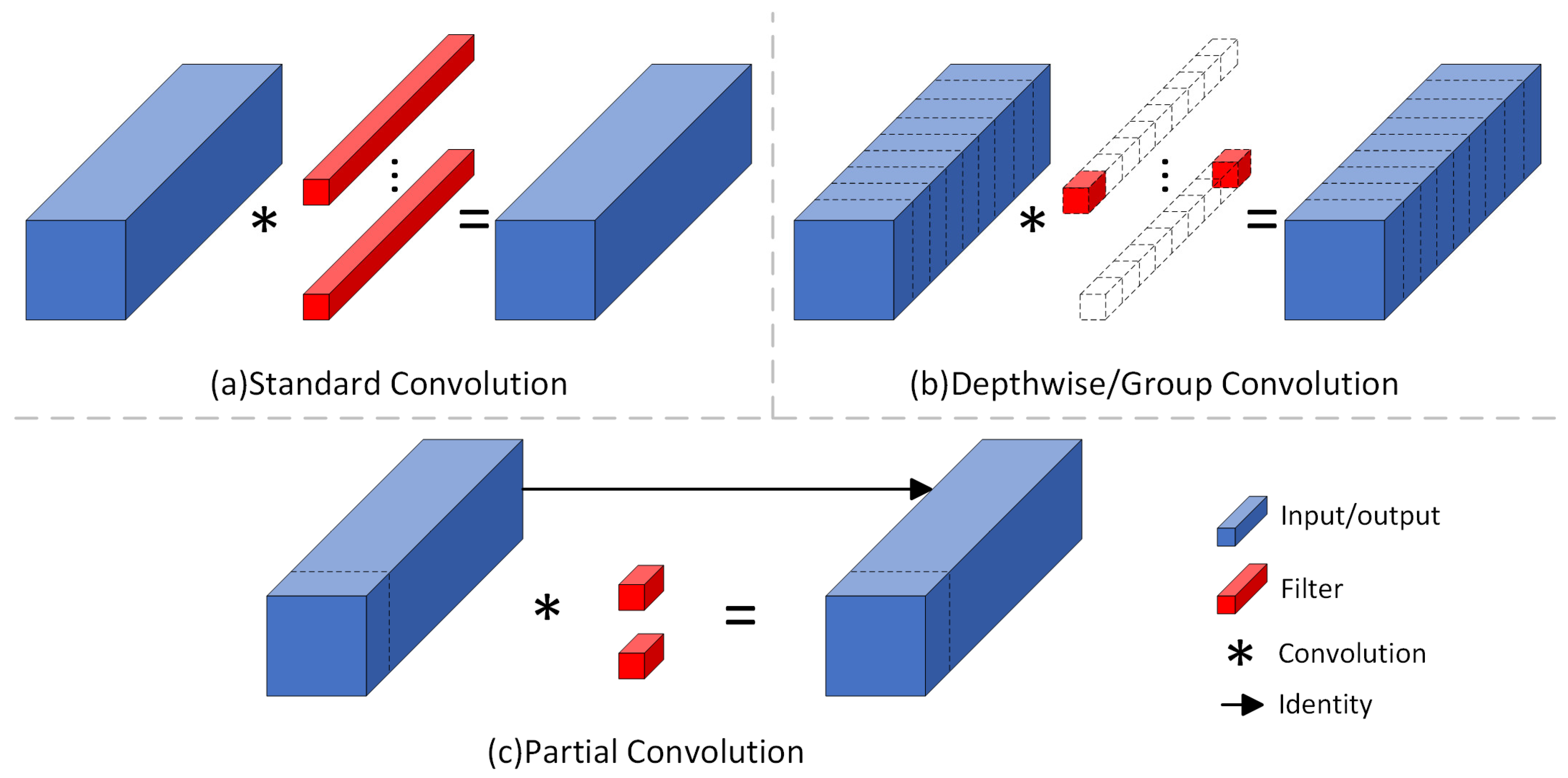

2.4.2. Partial Convolution

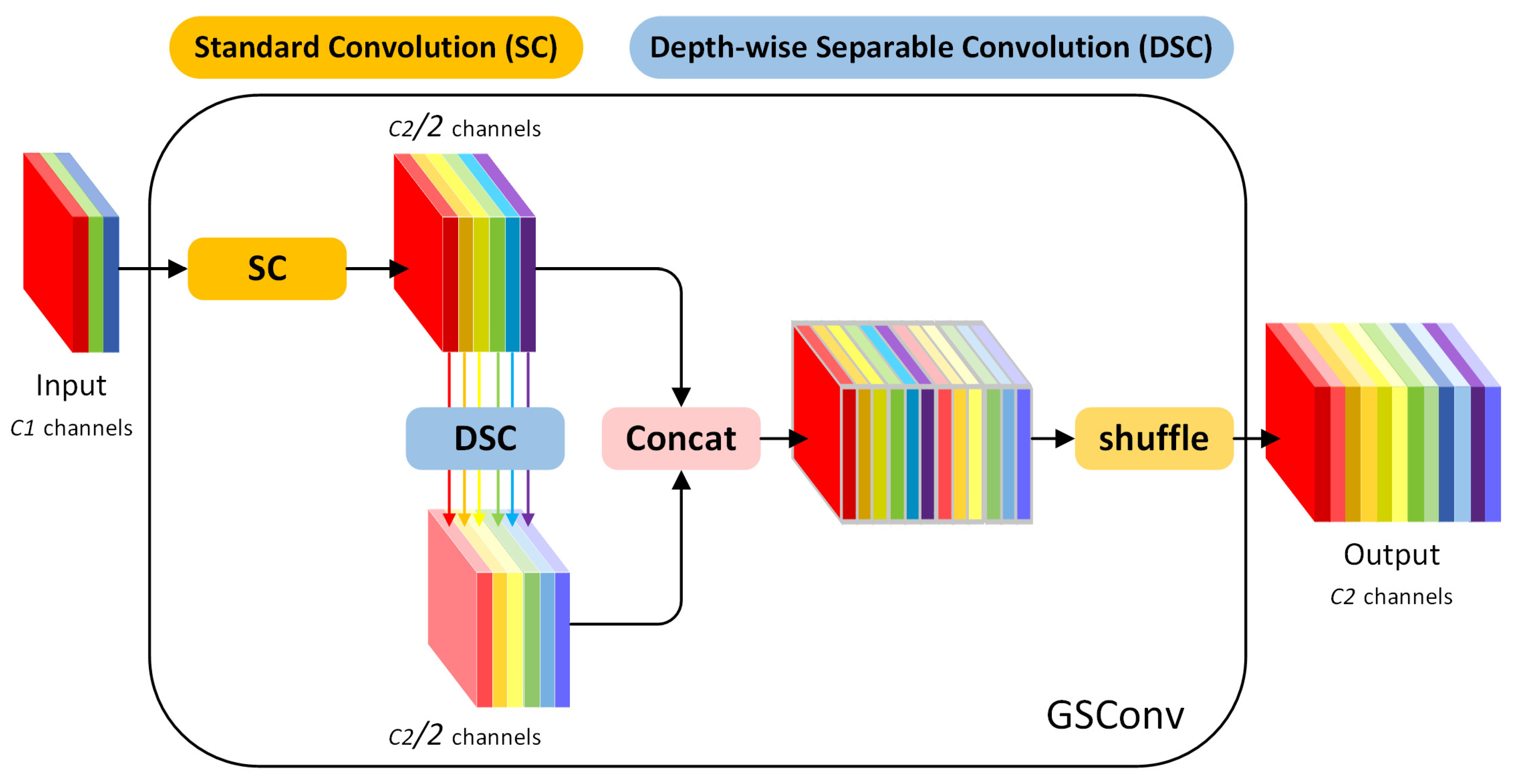

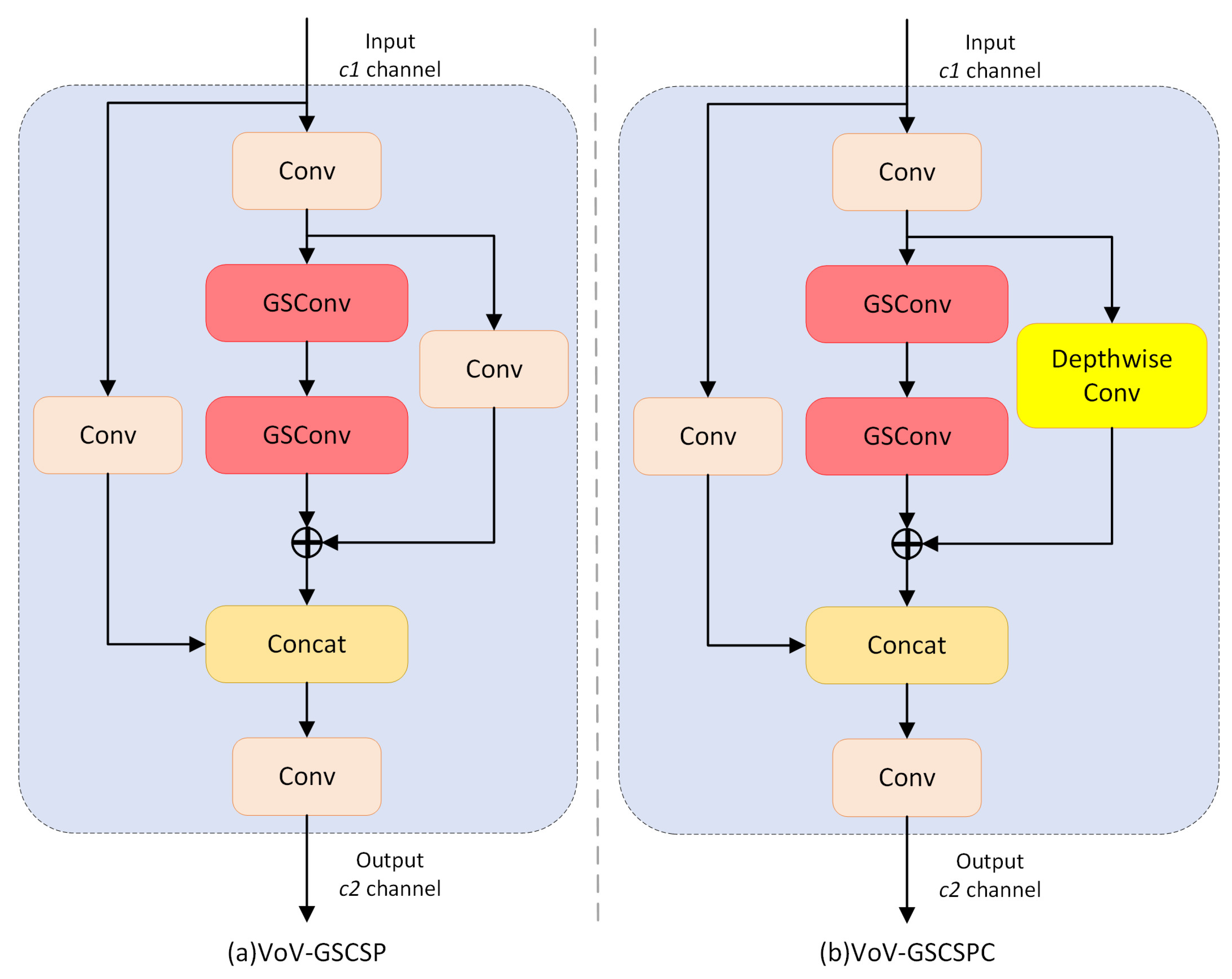

2.4.3. SlimNeck

2.5. Experimental Setup

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

3. Results

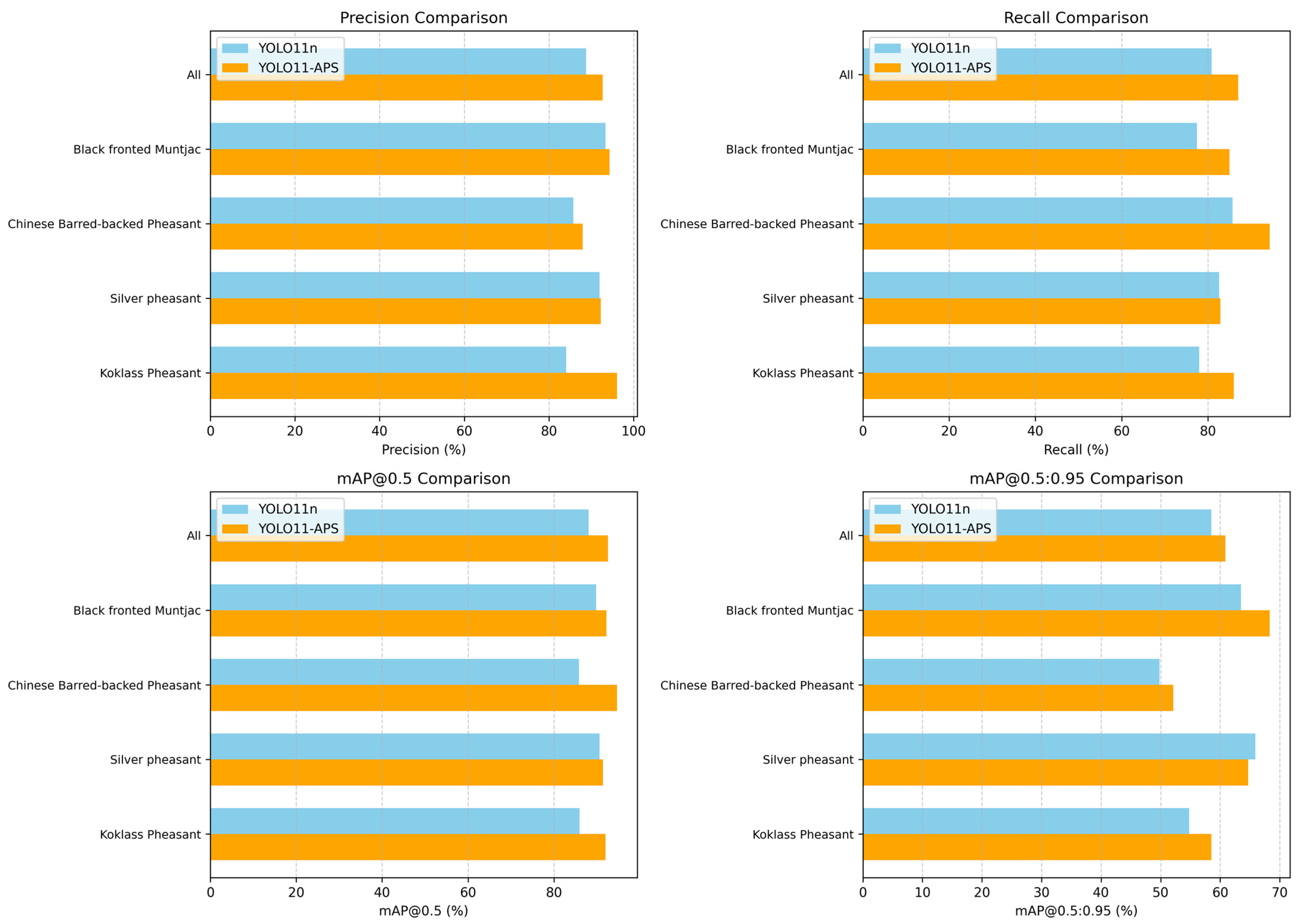

3.1. Class-Wise Detection Performance

3.2. Ablation Experiments

3.2.1. Effect of Improvement Modules

3.2.2. Attention Mechanisms Comparison Study

3.2.3. Convolutional Modules Comparison Study

3.2.4. Neck Structures Comparison Study

3.3. Contrast Experiments

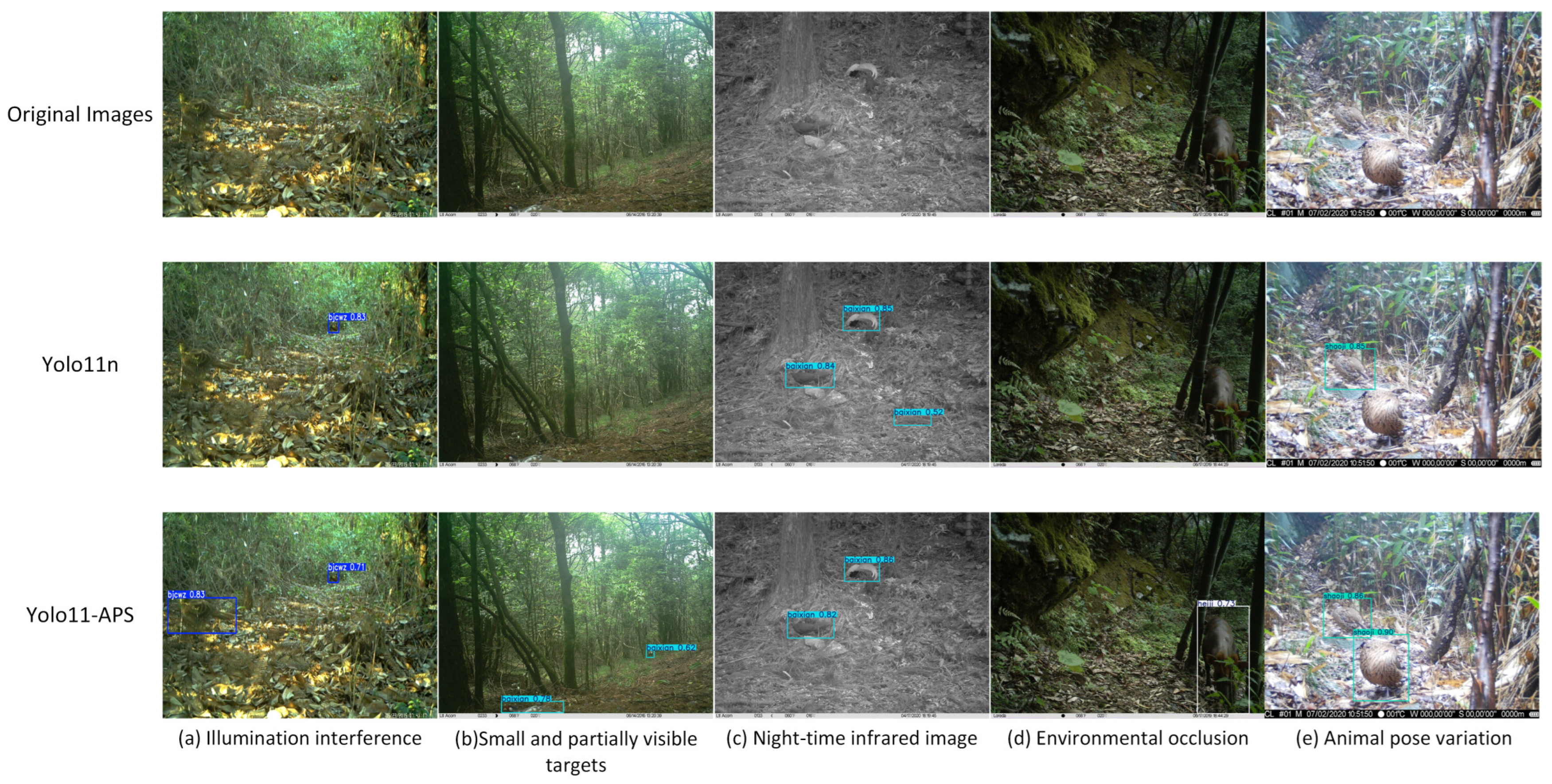

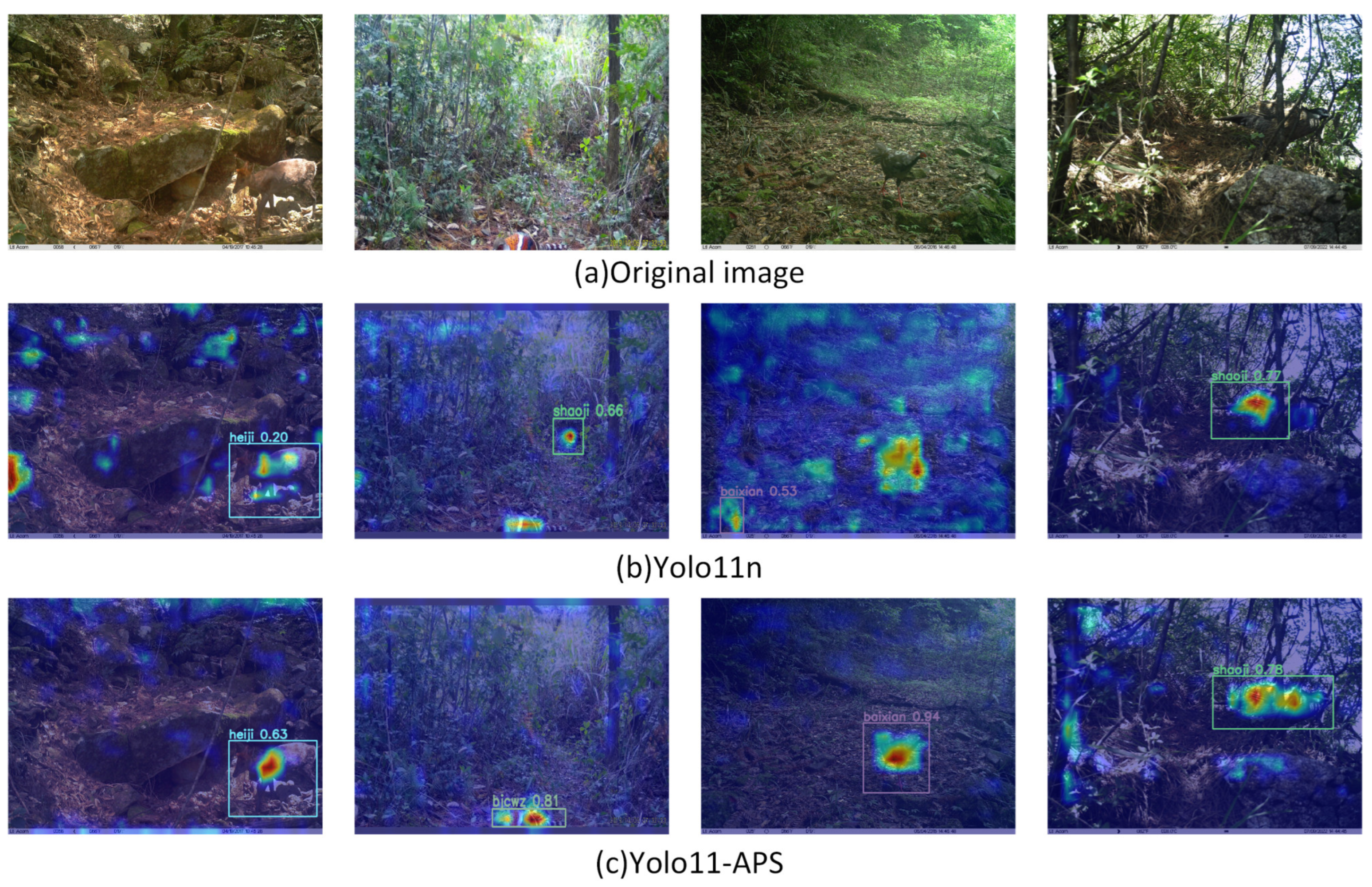

3.4. Visualized Analysis

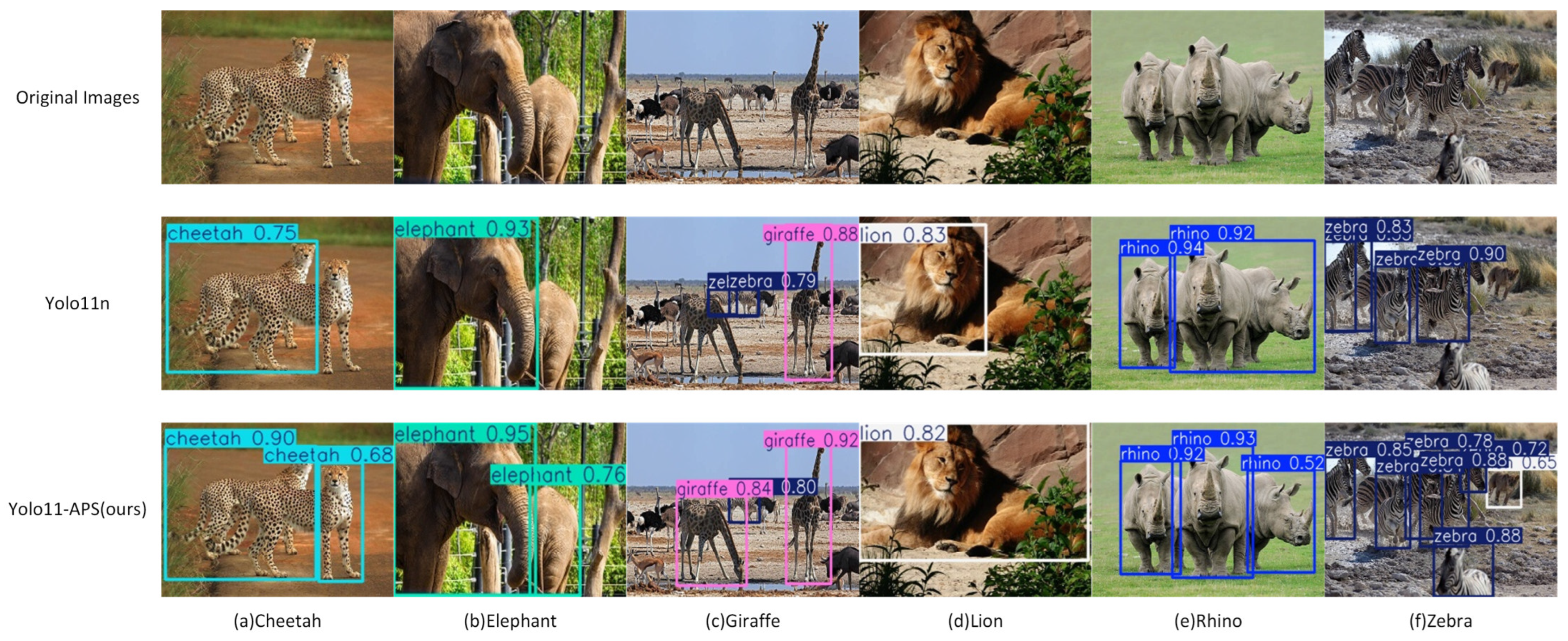

3.5. Cross-Dataset Model Validation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Watson, J.E.M.; Dudley, N.; Segan, D.B.; Hockings, M. The performance and potential of protected areas. Nature 2014, 515, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Lin, H.; Cui, G. A comparative analysis of the list of state key protected wild animals and other wildlife protection lists. Biodivers. Sci. 2023, 31, 22639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucera, T.E.; Barrett, R.H. A history of camera trapping. In Camera Traps in Animal Ecology; O’Connell, A.F., Nichols, J.D., Karanth, K.U., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kays, R.; Crofoot, M.C.; Jetz, W.; Wikelski, M. Terrestrial animal tracking as an eye on life and planet. Science 2015, 348, aaa2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, P. Technological advances in biodiversity monitoring: Applicability, opportunities and challenges. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 45, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, A.C.; Neilson, E.; Moreira, D.; Ladle, A.; Steenweg, R.; Fisher, J.T.; Bayne, E.; Boutin, S. Wildlife camera trapping: A review and recommendations for linking surveys to ecological processes. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowcliffe, J.M.; Carbone, C. Surveys using camera traps: Are we looking to a brighter future? Anim. Conserv. 2008, 11, 185–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, A.; Kosmala, M.; Lintott, C.; Simpson, R.; Smith, A.; Packer, C. Snapshot Serengeti, high-frequency annotated camera trap images of 40 mammalian species in an African savanna. Sci. Data 2015, 2, 150026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzzadeh, M.S.; Nguyen, A.; Kosmala, M.; Swanson, A.; Palmer, M.S.; Packer, C.; Clune, J. Automatically identifying, counting, and describing wild animals in camera-trap images with deep learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E5716–E5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willi, M.; Pitman, R.T.; Cardoso, A.W.; Locke, C.; Swanson, A.; Boyer, A.; Veldthuis, M.; Fortson, L. Identifying animal species in camera trap images using deep learning and citizen science. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2019, 10, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wäldchen, J.; Mäder, P. Machine learning for image based species identification. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 2216–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beery, S.; Van Horn, G.; Perona, P. Recognition in Terra Incognita. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Greenberg, S.; Taylor, G.W.; Kremer, S.C. Three critical factors affecting automated image species recognition performance for camera traps. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 3503–3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovalov, D.A.; Hillcoat, S.; Williams, G.; Birtles, R.A.; Gardiner, N.; Curnock, M.I. Individual Minke whale recognition using deep learning convolutional neural networks. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2018, 6, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, H.; Yuan, J.; Kays, R.; He, Z. Animal Scanner: Software for classifying humans, animals, and empty frames in camera trap images. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; He, Z.; Cao, G.; Cao, W. Animal detection from highly cluttered natural scenes using spatiotemporal object region proposals and patch verification. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2016, 18, 2079–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Little, R.; Mihaylova, L.; Delahay, R.; Cox, R. Wildlife surveillance using deep learning methods. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 9453–9466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Rothfus, T.A.; Ashour, A.S.; Si, L.; Du, C.; Ting, T. Varied channels region proposal and classification network for wildlife image classification under complex environment. IET Image Process. 2020, 14, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.-Q.; Li, T.; Liu, M.-T.; Li, X.-W.; Chen, B.-H. A systematic study of the class imbalance problem: Automatically identifying empty camera trap images using convolutional neural networks. Ecol. Inform. 2021, 64, 101350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carl, C.; Schönfeld, F.; Profft, I.; Klamm, A.; Landgraf, D. Automated detection of European wild mammal species in camera trap images with an existing and pre-trained computer vision model. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2020, 66, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, F.; Bouveyron, C.; Precioso, F. DeepWILD: Wildlife identification, localisation and estimation on camera trap videos using deep learning. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 75, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Rathod, V.; Sun, C.; Zhu, M.; Korattikara, A.; Fathi, A.; Fischer, I.; Wojna, Z.; Song, Y.; Guadarrama, S.; et al. Speed/Accuracy Trade-offs for Modern Convolutional Object Detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3296–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Chao, W.; Cheng, J.-K.; Zhou, M.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, X.; Ge, J.; Yu, L.; Feng, L. Animal detection and classification from camera trap images using different mainstream object detection architectures. Animals 2022, 12, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Lu, X. An efficient network for multi-scale and overlapped wildlife detection. Signal Image Video Process. 2023, 17, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.M.; Bhaduri, J.; Kumar, T.; Raj, K. WilDect-YOLO: An efficient and robust computer vision-based accurate object localization model for automated endangered wildlife detection. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 75, 101919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Spatial pyramid pooling in deep convolutional networks for visual recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 37, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path Aggregation Network for Instance Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 8759–8768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Xu, F. Intelligent detection method for wildlife based on deep learning. Sensors 2023, 23, 9669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibraheam, M.; Li, K.F.; Gebali, F. An accurate and fast animal species detection system for embedded devices. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 23462–23473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Fan, Q.; Zhao, C.; Li, S. RTAD: A real-time animal object detection model based on a large selective kernel and channel pruning. Information 2023, 14, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, G.; Zhang, S.; Mao, W.; Zhang, M. YOLO-SAG: An improved wildlife object detection algorithm based on YOLOv8n. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 83, 102791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakana, S.R.; Zhang, Y.; Twala, B. WildARe-YOLO: A lightweight and efficient wild animal recognition model. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 80, 102541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Ge, C.; Lu, R.; Song, S.; Chen, G.; Huang, Z.; Huang, G. On the Integration of Self-Attention and Convolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Kao, S.H.; He, H.; Zhuo, W.; Wen, S.; Lee, C.H.; Chan, S.H.G. Run, Don’t Walk: Chasing Higher FLOPs for Faster Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 12021–12031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhan, Z.; Ren, Q. Slim-neck by GSConv: A lightweight design for real-time detector architectures. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2024, 21, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Lee, C.C.; Hsieh, J.W.; Fan, K.C. CSL-YOLO: A new lightweight object detection system for edge computing. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.04829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep Learning with Depthwise Separable Convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1800–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Hwang, J.W.; Lee, S.; Bae, Y.; Park, J. An Energy and GPU-Computational Efficient Backbone Network for Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–17 June 2019; pp. 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D.; Lu, R.; Shen, S.; Xu, T.; Lang, X.; Ren, Z. Mixed local channel attention for object detection. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, R.; Niggemeier, L.; Hüttemann, M.; Kazerouni, A.; Aghdam, E.K.; Velichko, Y.; Bagci, U.; Merhof, D. Beyond Self-Attention: Deformable Large Kernel Attention for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024; pp. 1276–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Pan, X.; Song, S.; Li, L.E.; Huang, G. Vision Transformer with Deformable Attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 4784–48793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Xue, Z.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, Z.; Huang, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C. Rethinking Mobile Block for Efficient Attention-Based Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 1389–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, D.; Nalamada, T.; Arasanipalai, A.U.; Hou, Q. Rotate to Attend: Convolutional Triplet Attention Module. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2021; pp. 3138–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finder, S.E.; Amoyal, R.; Treister, E.; Freifeld, O. Wavelet Convolutions for Large Receptive Fields. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Tang, S.; Zhang, R.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Y. CGNet: A light-weight context guided network for semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 30, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Song, Y.; Song, T.; Yang, D.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L. LDConv: Linear deformable convolution for improving convolutional neural networks. Image Vis. Comput. 2024, 149, 105190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Verma, V.K.; Rai, P.; Namboodiri, V.P. HetConv: Heterogeneous Kernel-Based Convolutions for Deep CNNs. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 4830–4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Leichner, C.; Delakis, M.; Fornoni, M.; Luo, S.; Yang, F.; Wang, W.; Banbury, C.; Ye, C.; Akin, B.; et al. MobileNetV4: Universal Models for the Mobile Ecosystem. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. DETRs Beat YOLOs on Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X. Damo-YOLO: A report on real-time object detection design. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.15444. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Fu, Y.; Gu, L.; Yan, C.; Harada, T.; Huang, G. Frequency-aware feature fusion for dense image prediction. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 10763–10780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakana, S.R.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S. Digital Eye on Endangered Wildlife: Crafting Recognition Datasets through Semi-Automated Annotation. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Conference on Advances in Image Processing (ICAIP), Beijing, China, 17–19 November 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthiopoulos, J.; Fieberg, J.; Aarts, G.; Morales, J.M.; Haydon, D.T. Establishing the link between habitat selection and animal population dynamics. Ecol. Monogr. 2015, 85, 413–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Camera Name | Hikvision Network Camera |

| Model | DS-2XS6C8FZC-QYBS (6 mm) |

| Sensor | 1/1.8′′ Progressive Scan CMOS |

| Infrared Mode | Low-glow IR (850 nm) |

| Field of View | Horizontal 50° ± 5°, Vertical 20° ± 5° |

| Detection Range | Up to 15 m |

| Trigger Speed | <0.3 s |

| Exp | Configuration | P (%) | R (%) | mAP@0.5 (%) | mAP@0.5:0.95 (%) | Params (M) | GFLOPs | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | baseline | 88.9 | 80.9 | 88.1 | 58.5 | 2.58 | 6.3 | 5.25 |

| 2 | baseline + ACmix | 91 | 82.4 | 88.4 | 58.6 | 2.59 | 6.3 | 5.23 |

| 3 | baseline + PConv | 89 | 82.5 | 88.5 | 59.3 | 2.27 | 6 | 4.62 |

| 4 | baseline + SlimNeck | 90.4 | 86 | 89.6 | 59.6 | 2.48 | 5.8 | 5.05 |

| 5 | baseline + ACmix + PConv | 92 | 85.1 | 90.1 | 61.9 | 2.28 | 6.1 | 4.63 |

| 6 | baseline + ACmix + SlimNeck | 91.2 | 85.3 | 91.8 | 61.9 | 2.49 | 5.8 | 5.1 |

| 7 | baseline + PConv + SlimNeck | 90.4 | 83.8 | 91 | 61.6 | 2.31 | 5.6 | 4.73 |

| 8 | YOLO11-APS(ALL) | 92.7 | 87 | 92.6 | 62.2 | 2.32 | 5.6 | 4.75 |

| Method | P (%) | R (%) | mAP@0.5 (%) | mAP@0.5:0.95 (%) | Params (M) | GFLOPs | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv11 (Baseline) | |||||||

| +MLCA [41] | 90.9 | 81.6 | 87.7 | 58.5 | 2.53 | 6.3 | 5.13 |

| +DLKA [42] | 92.3 | 82.3 | 88.7 | 59.5 | 3.37 | 6.9 | 6.73 |

| +DAT [43] | 91.3 | 82 | 87.8 | 58.5 | 2.61 | 6.9 | 5.29 |

| +iRMB [44] | 93.1 | 79.7 | 87.8 | 59 | 2.60 | 8.2 | 5.26 |

| +Triplet Attention [45] | 90.8 | 81.1 | 88.2 | 59.4 | 2.58 | 6.4 | 5.14 |

| +ACmix (ours) | 91 | 82.4 | 88.4 | 58.6 | 2.59 | 6.3 | 5.23 |

| Method | P (%) | R (%) | mAP@0.5 (%) | mAP@0.5:0.95 (%) | Params (M) | GFLOPs | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv11 (Baseline) | |||||||

| +WTConv [46] | 91.8 | 80.3 | 88.1 | 56.6 | 2.79 | 7.5 | 5.6 |

| +CG Block [47] | 92.6 | 83.5 | 89.6 | 58.6 | 2.82 | 7.1 | 5.68 |

| +LDConv [48] | 90.9 | 84.1 | 90.9 | 59 | 2.81 | 7.6 | 5.65 |

| +HetConv [49] | 92.1 | 82.4 | 88.5 | 58.9 | 2.8 | 7.5 | 5.62 |

| +UIB [50] | 89.3 | 78.2 | 84.7 | 56 | 2.83 | 7.2 | 5.7 |

| +PConv (ours) | 89 | 82.5 | 88.5 | 59.3 | 2.27 | 6 | 4.62 |

| Method | P (%) | R (%) | mAP@0.5 (%) | mAP@0.5:0.95 (%) | Params (M) | GFLOPs | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv11 (Baseline) | |||||||

| +CCFF [51] | 90.9 | 82.1 | 87.4 | 56.1 | 1.8 | 5.3 | 3.74 |

| +RepGFPN [52] | 91.5 | 79.3 | 84.9 | 57.9 | 2.89 | 6.7 | 5.83 |

| +FreqFusion [53] | 88.7 | 83.4 | 87 | 56.1 | 2.43 | 6.8 | 4.96 |

| +SlimNeck (ours) | 90.4 | 86 | 89.6 | 59.6 | 2.48 | 5.8 | 5.05 |

| Model | P (%) | R (%) | mAP@0.5 (%) | mAP@0.5:0.95 (%) | Params (M) | GFLOPs | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv3-tiny | 81.4 | 79.5 | 81.6 | 45.1 | 8.67 | 12.9 | 16.6 |

| YOLOv5n | 91.1 | 82 | 86.8 | 55.2 | 1.76 | 4.1 | 3.73 |

| YOLOv7 | 92.3 | 83.9 | 89.6 | 59 | 6.02 | 13 | 11.7 |

| YOLOv8n | 89.7 | 81.9 | 87.3 | 59.4 | 3.01 | 8.1 | 5.39 |

| YOLOv10n | 86.5 | 82.5 | 87.5 | 57.9 | 2.7 | 8.2 | 5.51 |

| YOLOv12n | 91.3 | 79.1 | 86.7 | 57.9 | 2.56 | 6.3 | 5.3 |

| Faster R-CNN | 81.8 | 81.7 | 86 | 46.1 | 28.3 | 55.87 | 108 |

| SSD | 91.7 | 85.7 | 87.1 | 52.6 | 24.15 | 30.58 | 92.39 |

| Cascade R-CNN | 87.9 | 81.2 | 83.4 | 47 | 56.09 | 83.67 | 214 |

| DETR | 87.9 | 86.7 | 87.5 | 53.1 | 41.56 | 29.23 | 163 |

| YOLO11n | 88.9 | 80.9 | 88.1 | 58.5 | 2.58 | 6.3 | 5.25 |

| YOLO11-APS | 92.7 | 87 | 92.6 | 60.9 | 2.32 | 5.6 | 4.75 |

| Model | P (%) | R (%) | mAP@0.5 (%) | mAP@0.5:0.95 (%) | Params (M) | GFLOPs | Model Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLO11n | 96.4 | 90 | 97 | 85 | 2.58 | 6.3 | 5.25 |

| YOLO11-APS | 94 | 92.7 | 97.3 | 85.2 | 2.32 | 5.6 | 4.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du, Z.; Wu, D.; Wen, Q.; Xu, F.; Liu, Z.; Li, C.; Luo, R. An Improved Lightweight Model for Protected Wildlife Detection in Camera Trap Images. Sensors 2025, 25, 7331. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237331

Du Z, Wu D, Wen Q, Xu F, Liu Z, Li C, Luo R. An Improved Lightweight Model for Protected Wildlife Detection in Camera Trap Images. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7331. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237331

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Zengjie, Dasheng Wu, Qingqing Wen, Fengya Xu, Zhongbin Liu, Cheng Li, and Ruikang Luo. 2025. "An Improved Lightweight Model for Protected Wildlife Detection in Camera Trap Images" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7331. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237331

APA StyleDu, Z., Wu, D., Wen, Q., Xu, F., Liu, Z., Li, C., & Luo, R. (2025). An Improved Lightweight Model for Protected Wildlife Detection in Camera Trap Images. Sensors, 25(23), 7331. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237331