Impacts of Mesoscale Eddy Structural Characteristics on Matched-Field Localization Uncertainty

Highlights

- The distribution of localization errors caused by eddies exhibits regularity.

- The mechanism underlying the regularity of localization error distribution.

- The localization errors caused by eddies are limited.

- The parameters of eddies can theoretically be obtained through matched field inversion.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

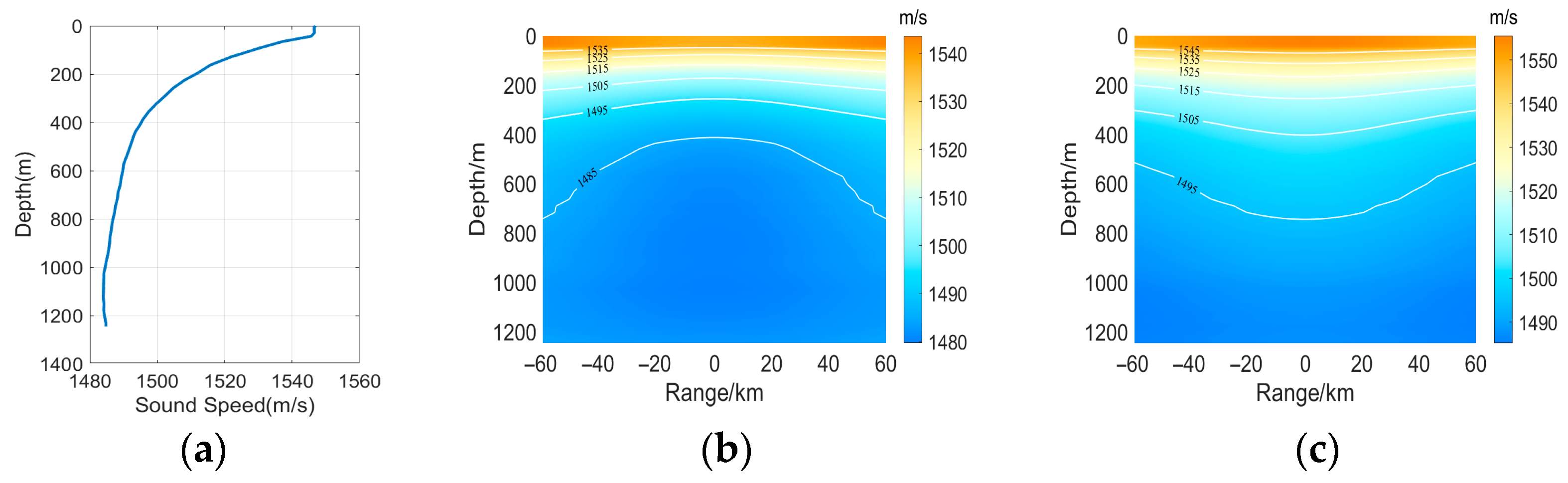

2.1. Gaussian Eddy Model

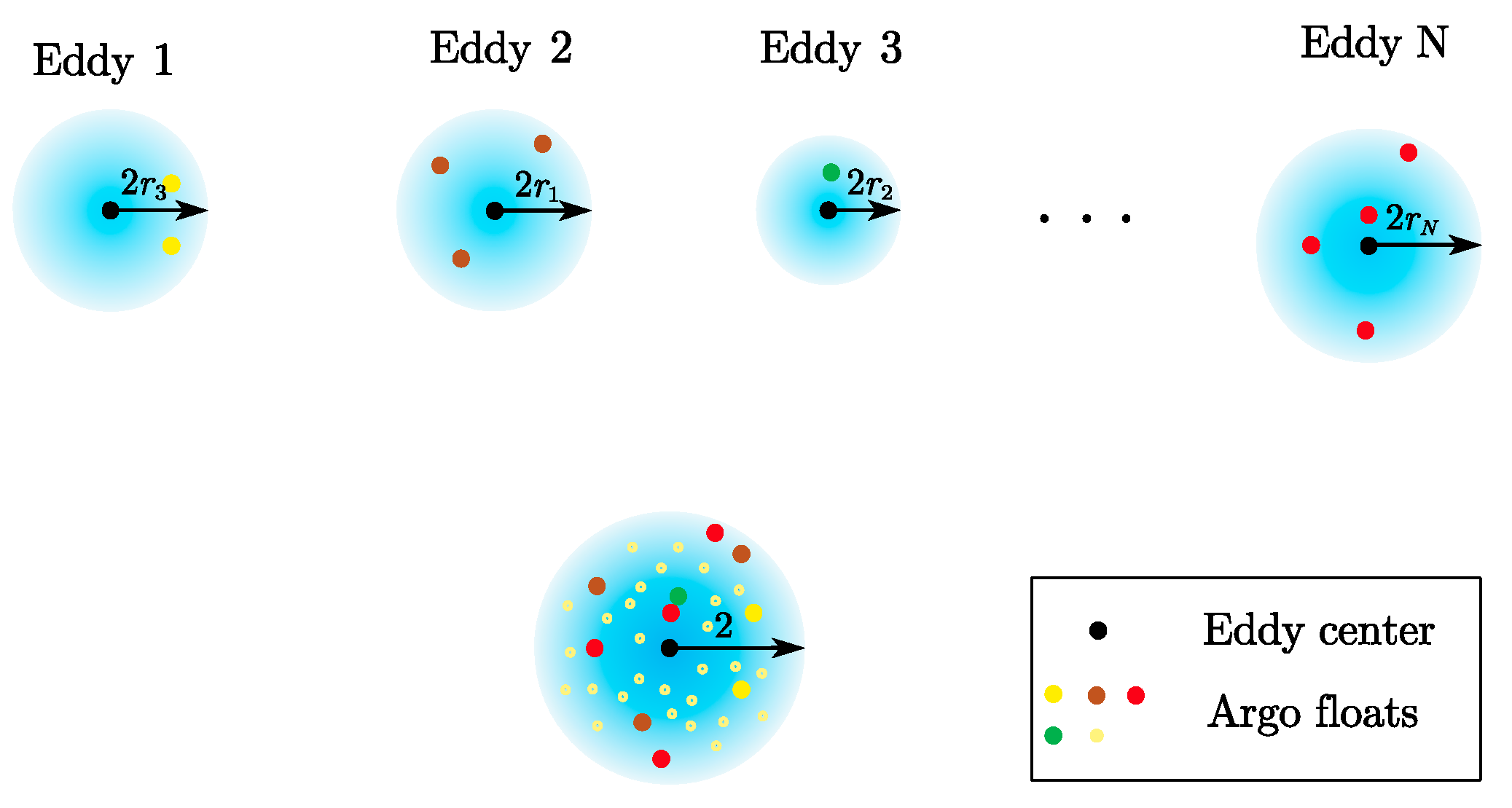

2.2. Composite Analysis of the Vertical Structure of Mesoscale Eddies

2.2.1. Data

2.2.2. Data Processing Procedure

2.3. Conventional Matched Field Processing

3. Results

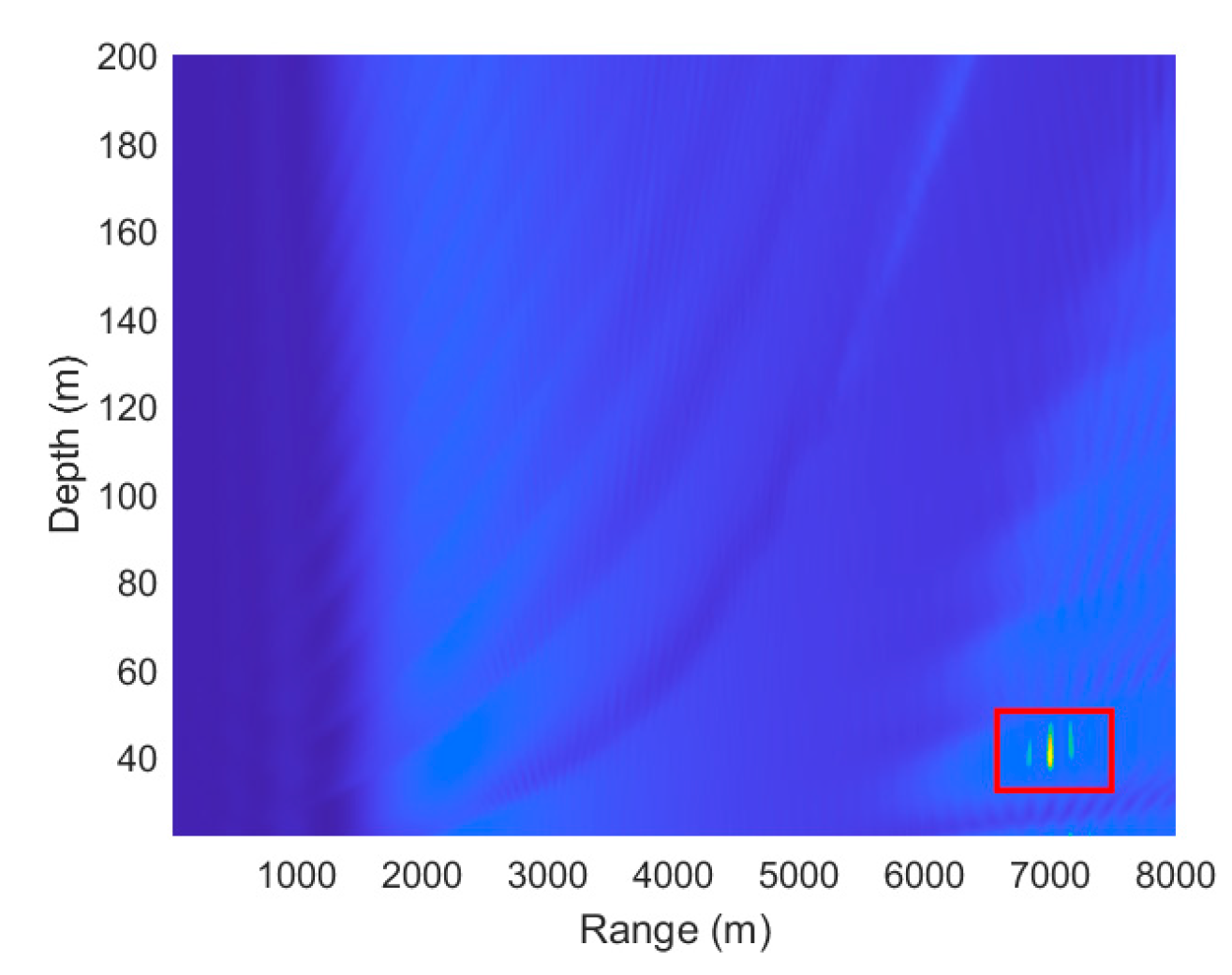

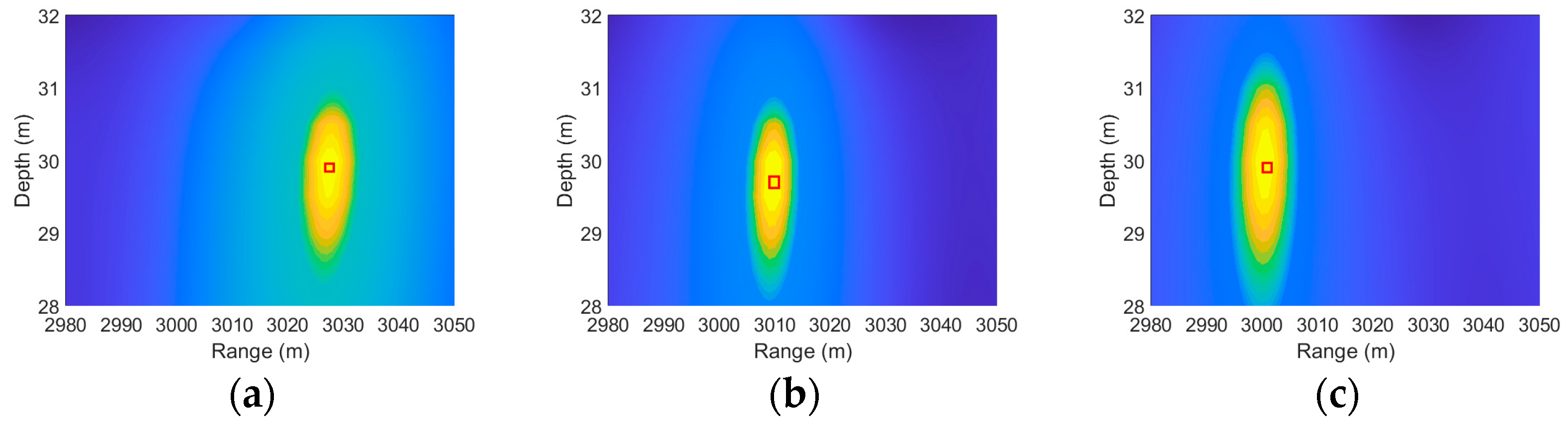

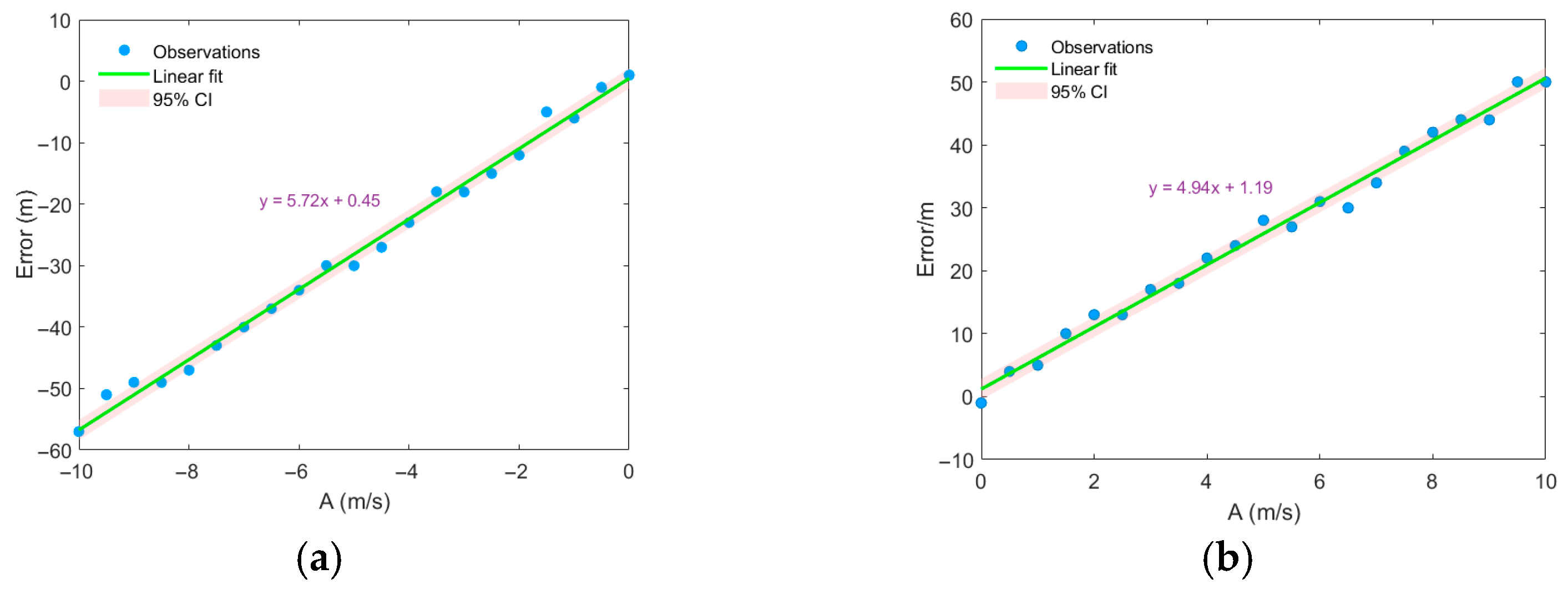

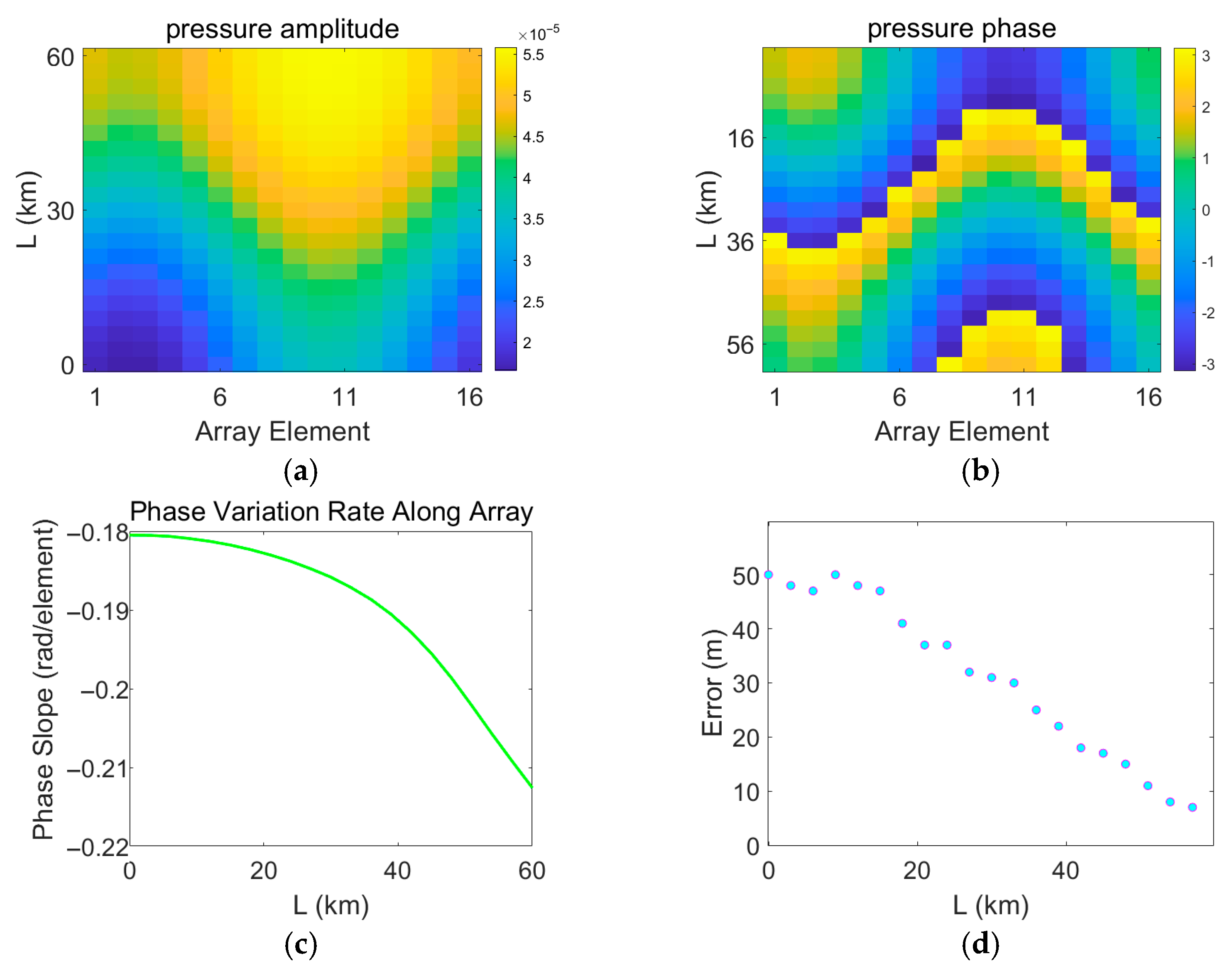

3.1. Anticyclone Eddy

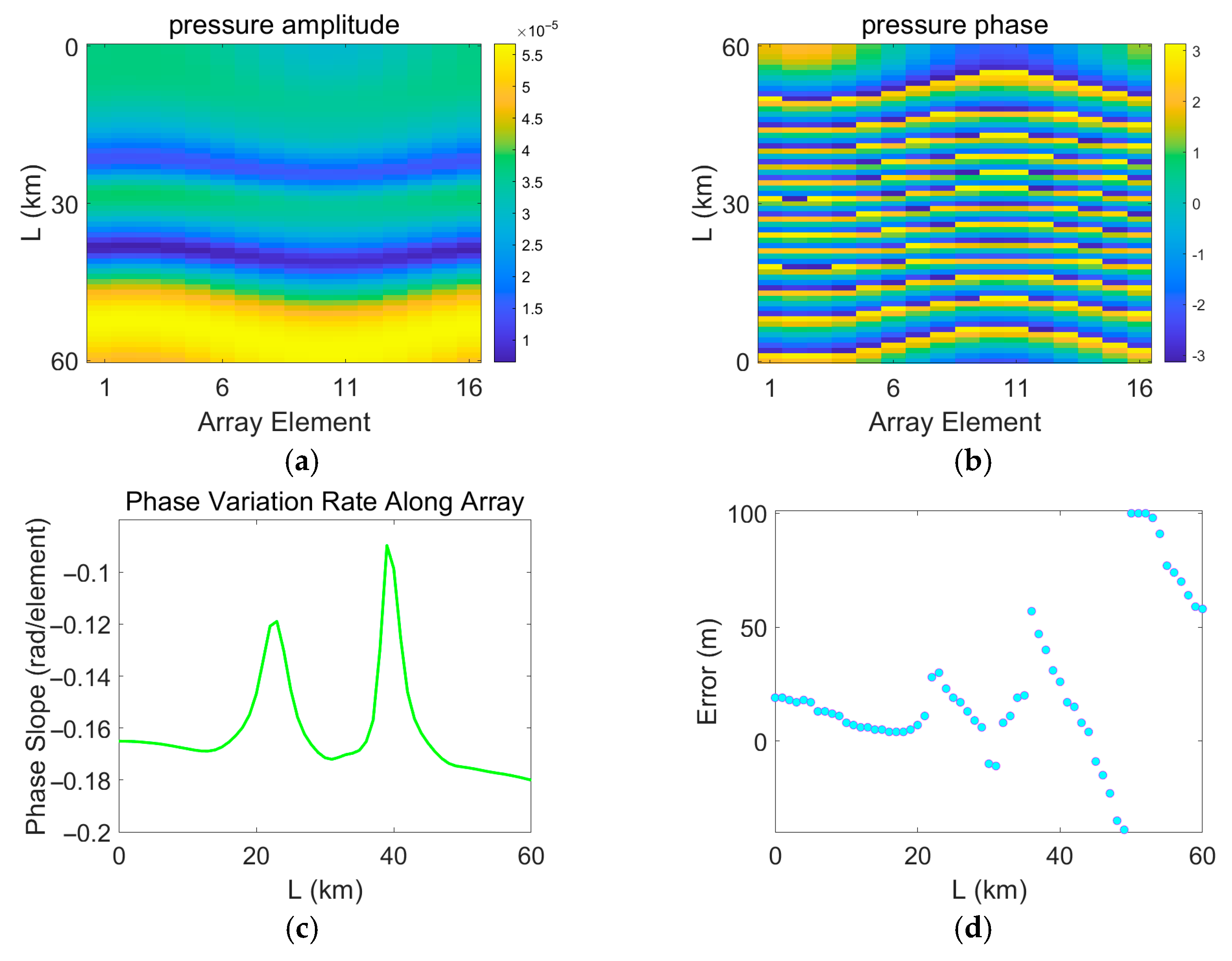

3.2. Cyclone Eddy

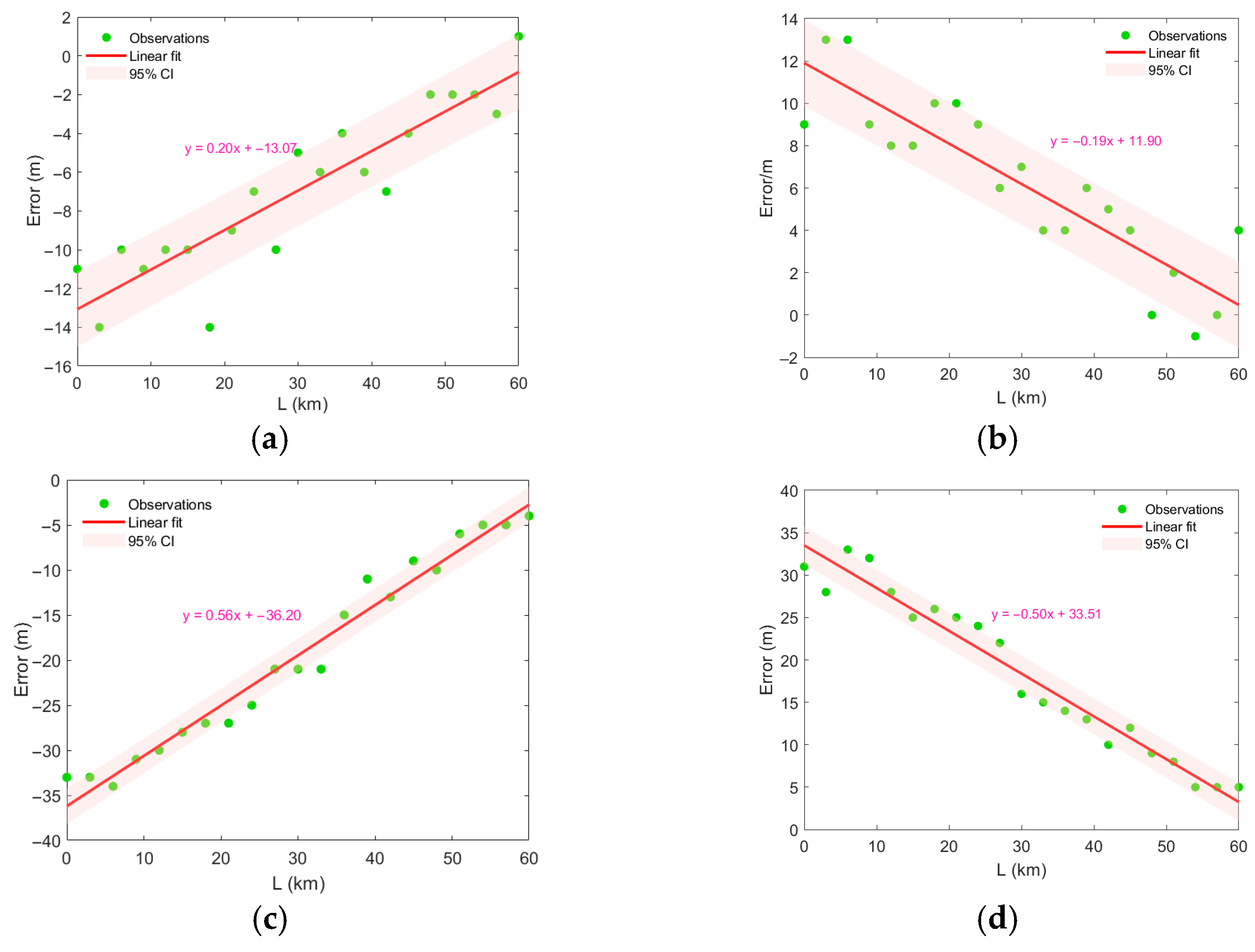

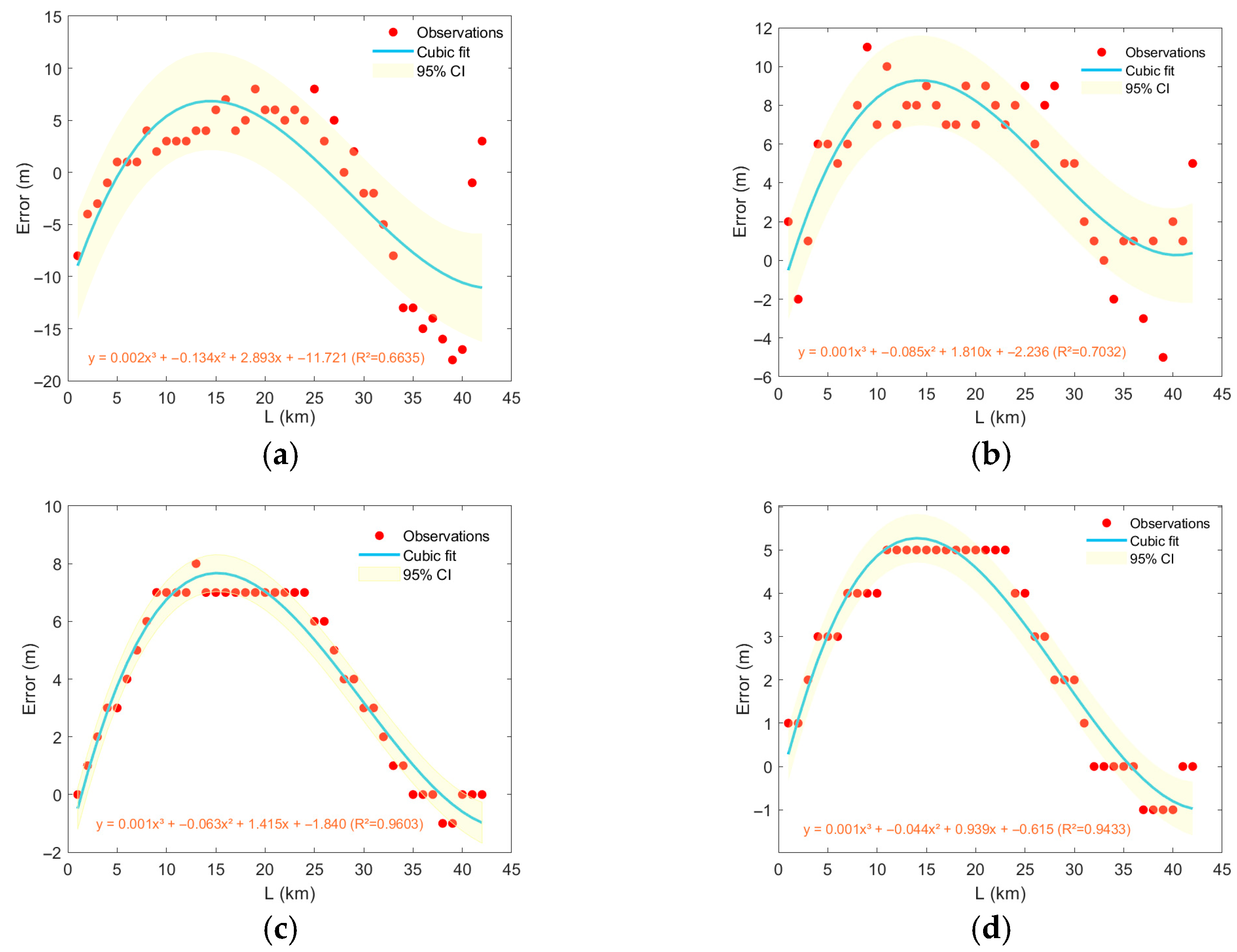

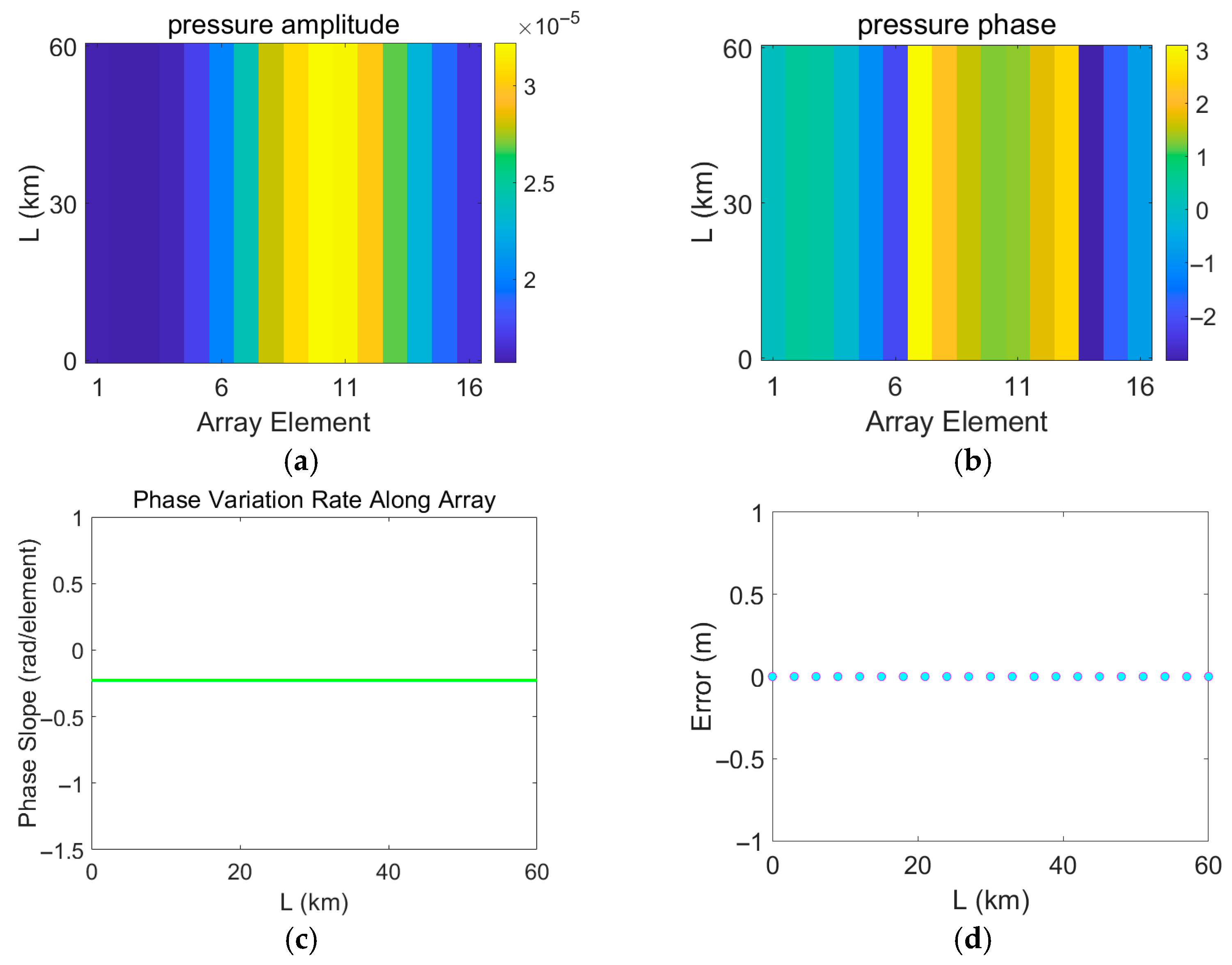

3.3. Distance Estimation Error Under the Perturbation of the Gaussian Eddy Model

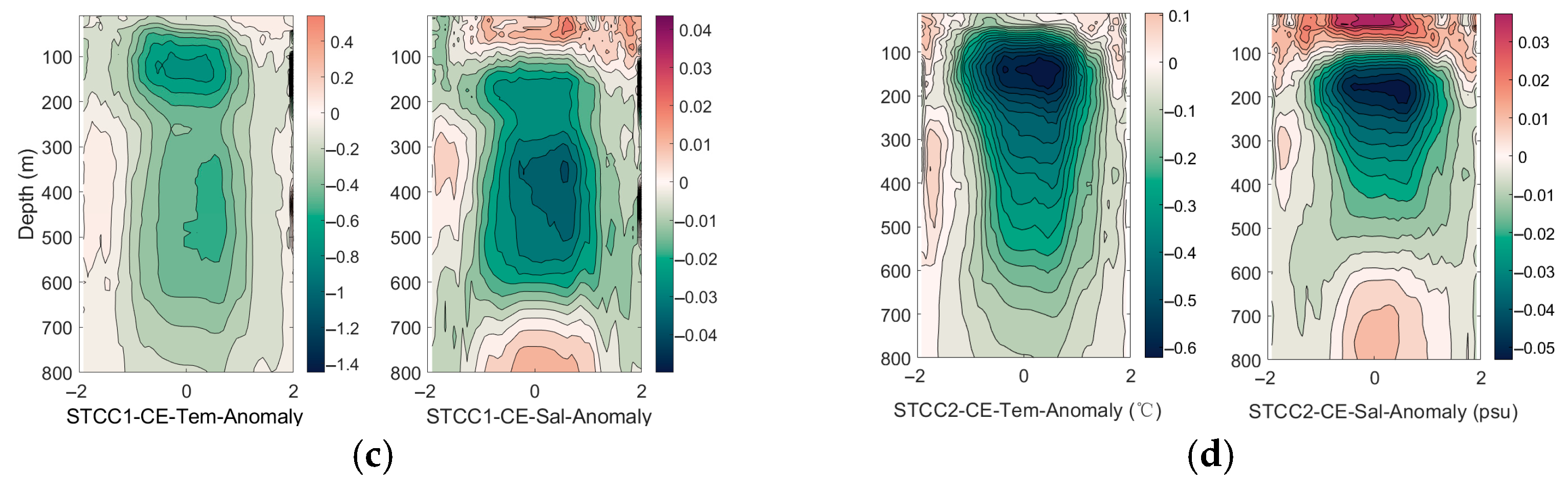

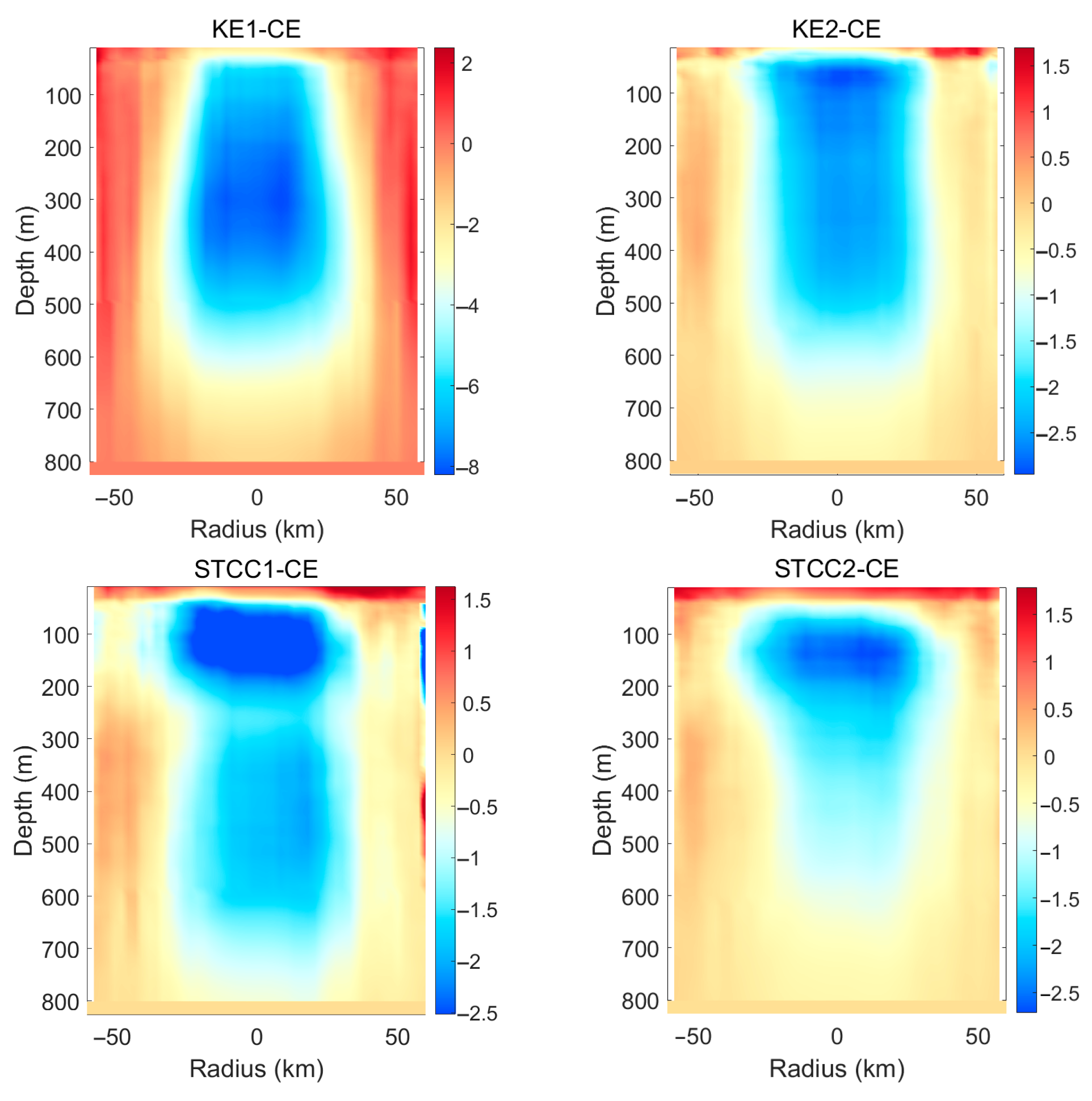

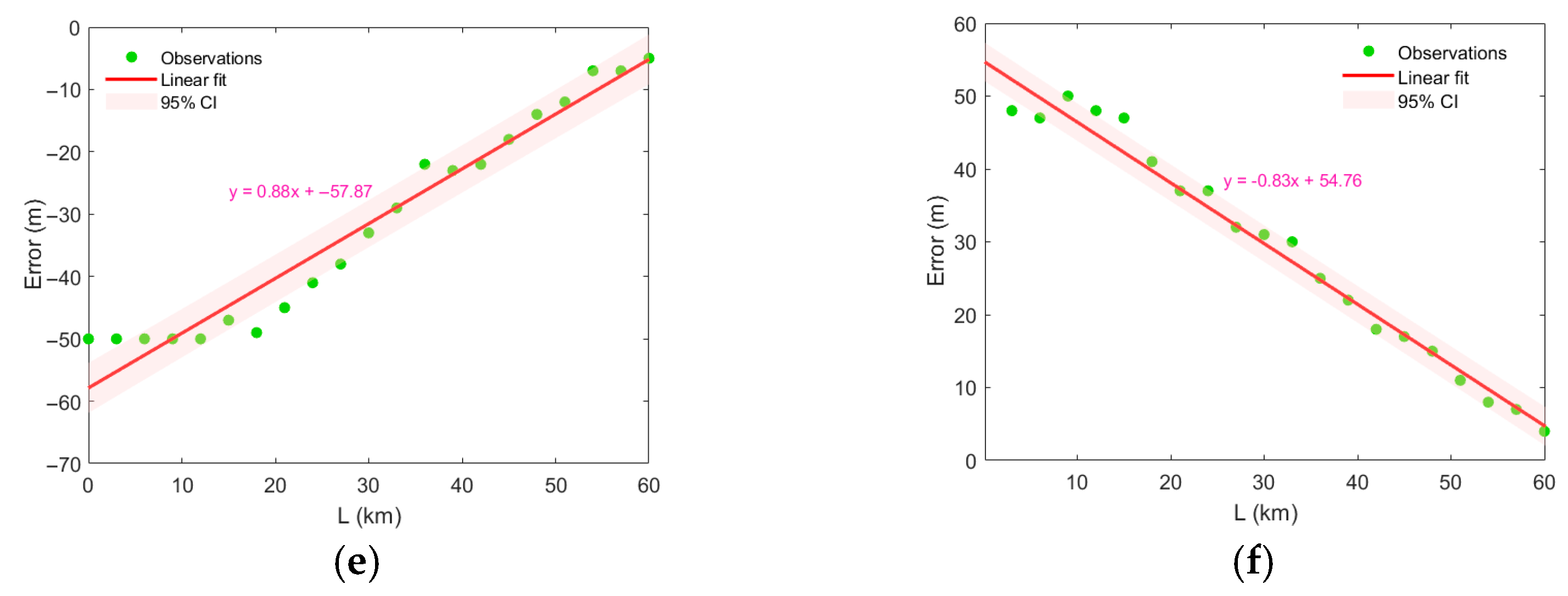

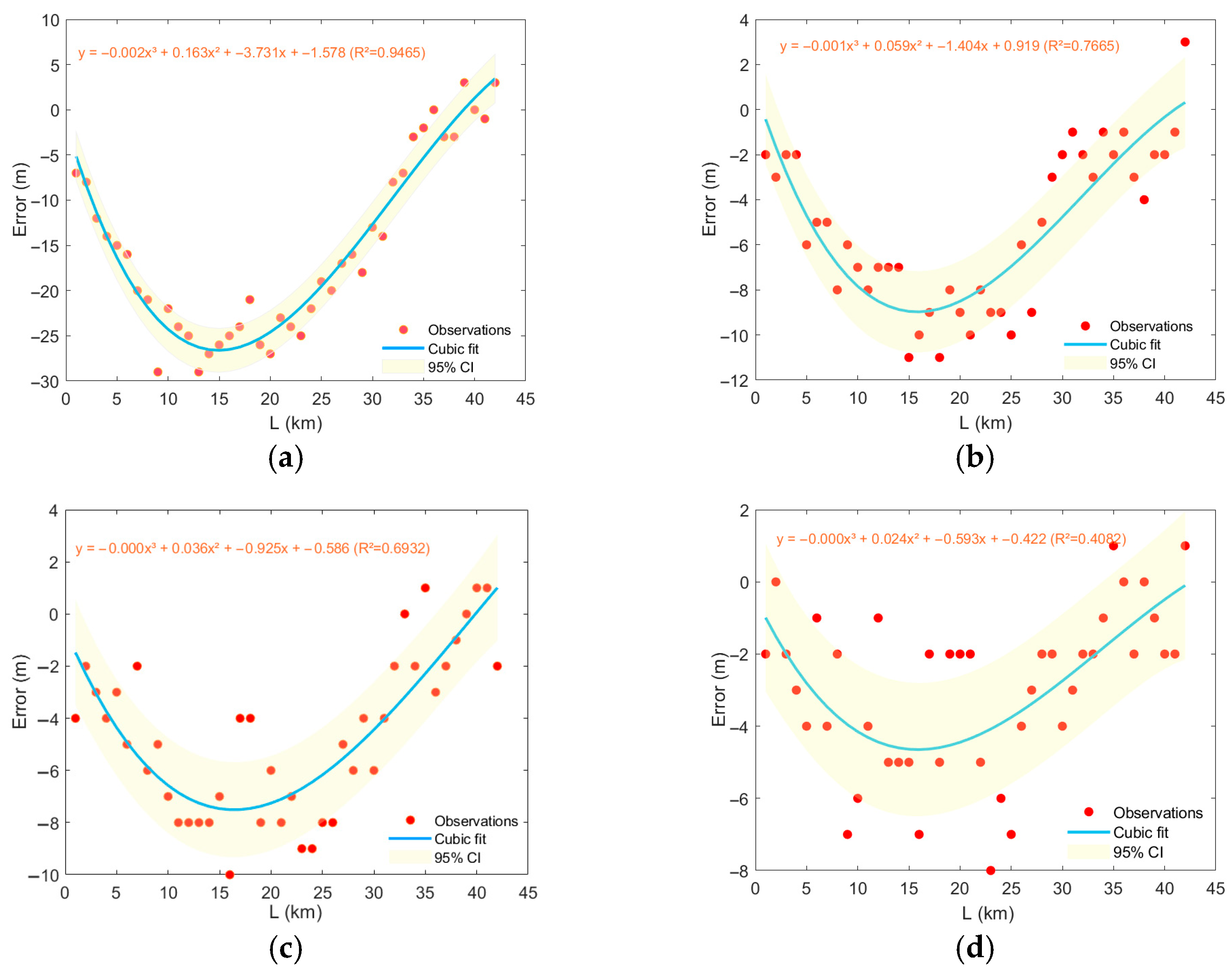

3.4. Impact of the Synthetic Vertical Structure of Mesoscale Eddies in Different Regions of the Northwestern Pacific on Localization Error

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, H.; Qiu, B.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z. Doubling of Surface Oceanic Meridional Heat Transport by Non-Symmetry of Mesoscale Eddies. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Wang, S.; Wu, L.; Chang, P.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, B.; Ma, X.; Qiu, B.; Small, J.; Jin, F.-F.; et al. Maintenance of Mid-Latitude Oceanic Fronts by Mesoscale Eddies. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastano, A.C.; Owens, G.E. On the Acoustic Characteristics of a Gulf Stream Cyclonic Ring. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1973, 3, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.N. Calculations of Sound Propagation through an Eddy. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1980, 67, 1180–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, K.D.; Campbell, R.L. Three-Dimensional Parabolic Equation Modeling of Mesoscale Eddy Deflection. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2016, 139, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, J.A.; Booker, J.R. Long-range Propagation of Sound through Oceanic Mesoscale Structures. J. Geophys. Res. 1983, 88, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Dong, C.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Nan, F.; Ren, Q.; Chen, Z. Effects of a Subsurface Eddy on Acoustic Propagation in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean. JMSE 2023, 11, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colosi, J.A.; Rudnick, D.L. Observations of Upper Ocean Sound-Speed Structures in the North Pacific and Their Effects on Long-Range Acoustic Propagation at Low and Mid-Frequencies. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2020, 148, 2040–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Piao, S.; Gong, L.; Zhang, M.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, S. The Effect of Mesoscale Eddy on the Characteristic of Sound Propagation. JMSE 2021, 9, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; Han, K.; Wu, Y.; Li, P.; Guo, W. Modulation of Deep-Sea Acoustic Field Interference Patterns by Mesoscale Eddies. JMSE 2025, 13, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colosi, J.A.; Cornuelle, B.D.; Dzieciuch, M.A.; Worcester, P.F.; Chandrayadula, T.K. Observations of Phase and Intensity Fluctuations for Low-Frequency, Long-Range Transmissions in the Philippine Sea and Comparisons to Path-Integral Theory. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2019, 146, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worcester, P.F.; Dzieciuch, M.A.; Mercer, J.A.; Andrew, R.K.; Dushaw, B.D.; Baggeroer, A.B.; Heaney, K.D.; D’Spain, G.L.; Colosi, J.A.; Stephen, R.A.; et al. The North Pacific Acoustic Laboratory Deep-Water Acoustic Propagation Experiments in the Philippine Sea. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2013, 134, 3359–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worcester, P.F.; Spindel, R.C. North Pacific Acoustic Laboratory. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2005, 117, 1499–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, M.; Gudimenko, A.; Luchin, V.; Tyschenko, A.; Petrov, P. The Parameterization of the Sound Speed Profile in the Sea of Japan and Its Perturbation Caused by a Synoptic Eddy. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinich, M.J. Maximum Likelihood Estimation of the Position of a Radiating Source in a Waveguide. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1979, 66, 480–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucker, H.P. Use of Calculated Sound Fields and Matched-Field Detection to Locate Sound Sources in Shallow Water. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1976, 59, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, R. Range and Depth Estimation by Line Arrays in Shallow Water. Signal Process. 1981, 3, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capon, J.; Greenfield, R.J.; Kolker, R.J. Multidimensional Maximum-Likelihood Processing of a Large Aperture Seismic Array. Proc. IEEE 1967, 55, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’spain, G.L.; Murray, J.J.; Hodgkiss, W.S.; Booth, N.O.; Schey, P.W. Mirages in Shallow Water Matched Field Processing. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1999, 105, 3245–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, E.C. Source Depth Estimation in Waveguides. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1985, 77, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, E.C.; Clay, C.S.; Wang, Y.Y. Passive Harmonic Source Ranging in Waveguides by Using Mode Filter. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1985, 78, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.C. Effectiveness of Mode Filtering: A Comparison of Matched-Field and Matched-Mode Processing. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1990, 87, 2072–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.C. A Method of Range and Depth Estimation by Modal Decomposition. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1987, 82, 1736–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battle, D.J.; Gerstoft, P.; Hodgkiss, W.S.; Kuperman, W.A.; Nielsen, P.L. Bayesian Model Selection Applied to Self-Noise Geoacoustic Inversion. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2004, 116, 2043–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, N.R.; Jiang, Y. Geoacoustic Inversion of Broadband Data by Matched Beam Processing. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2005, 117, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, L.; Gangopadhyay, A.; Da Silveira, I.C.A. A Parametric Model for the Brazil Current Meanders and Eddies off Southeastern Brazil. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, 2006GL026092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, L.; Xu, W.; Li, M. Analysis of Acoustic Field Characteristics of Mesoscale Eddies throughout Their Complete Life Cycle. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 11, 1471670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Dong, C.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Yu, K. Vertical Structure Anomalies of Oceanic Eddies in the Kuroshio Extension Region: 3-D Eddy in the Kuroshio Extension Region. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2017, 122, 1476–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaigneau, A.; Le Texier, M.; Eldin, G.; Grados, C.; Pizarro, O. Vertical Structure of Mesoscale Eddies in the Eastern South Pacific Ocean: A Composite Analysis from Altimetry and Argo Profiling Floats. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116, 2011JC007134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Brandt, P.; Chang, P.; Schütte, F.; Yang, X.; Yan, J.; Zeng, J. Mesoscale Eddies in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean: Three-Dimensional Eddy Structures and Heat/Salt Transports. JGR Ocean. 2017, 122, 9795–9813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppler, L.; Cravatte, S.; Chaigneau, A.; Pegliasco, C.; Gourdeau, L.; Singh, A. Observed Characteristics and Vertical Structure of Mesoscale Eddies in the Southwest Tropical Pacific. JGR Ocean. 2018, 123, 2731–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Three-Dimensional Structures of Mesoscale Eddies in the Subtropical Countercurrent and Kuroshio Extension Regions and Their Vertical Normal Modes Analysis. J. Mar. Syst. 2025, 250, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelton, D.B.; Schlax, M.G.; Samelson, R.M. Global Observations of Nonlinear Mesoscale Eddies. Prog. Oceanogr. 2011, 91, 167–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelton, D.B.; Schlax, M.G. Global Observations of Oceanic Rossby Waves. Science 1996, 272, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, W.B.; Wong, A.P.S. An Improved Calibration Method for the Drift of the Conductivity Sensor on Autonomous CTD Profiling Floats by θ–S Climatology. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2009, 56, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Xu, G.; Gao, D.; Ma, S. Application of a Spectral Scheme for Simulating Slowly Horizontally Varying Three-Dimensional Ocean Acoustic Propagation. Ocean Eng. 2026, 343, 123035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Tang, Y. The Interannual Variability of Eddy Kinetic Energy in the Kuroshio Large Meander Region and Its Relationship to the Kuroshio Latitudinal Position at 140° E. JGR Ocean. 2022, 127, e2021JC017915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Xiao, W.; Wang, Y. Optimization of Route Planning Based on Active Towed Array Sonar for Underwater Search and Rescue. Ocean Eng. 2025, 330, 121249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Longitude/Latitude |

|---|---|

| KE 1 | 135° E–165° E, 30° N–45° N |

| KE 2 | 165° E–195° E, 30° N–45° N |

| STCC1 | 135° E–165° E, 15° N–30° N |

| STCC2 | 165° E–195° E, 15° N–30° N |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shang, L.; Han, K.; Wang, N.; Wu, Y.; Xu, G.; Li, P.; Guo, W. Impacts of Mesoscale Eddy Structural Characteristics on Matched-Field Localization Uncertainty. Sensors 2025, 25, 6842. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226842

Shang L, Han K, Wang N, Wu Y, Xu G, Li P, Guo W. Impacts of Mesoscale Eddy Structural Characteristics on Matched-Field Localization Uncertainty. Sensors. 2025; 25(22):6842. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226842

Chicago/Turabian StyleShang, Longquan, Kaifeng Han, Ning Wang, Yanqun Wu, Guojun Xu, Pingzheng Li, and Wei Guo. 2025. "Impacts of Mesoscale Eddy Structural Characteristics on Matched-Field Localization Uncertainty" Sensors 25, no. 22: 6842. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226842

APA StyleShang, L., Han, K., Wang, N., Wu, Y., Xu, G., Li, P., & Guo, W. (2025). Impacts of Mesoscale Eddy Structural Characteristics on Matched-Field Localization Uncertainty. Sensors, 25(22), 6842. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226842