1. Introduction

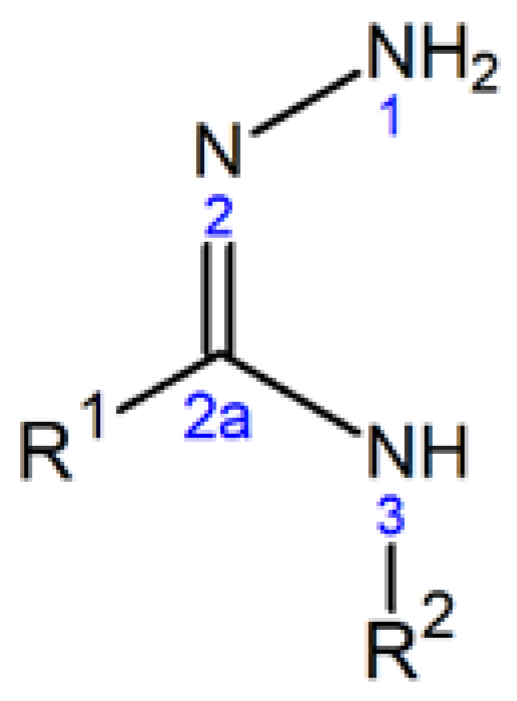

Amidrazones containing a characteristic N–N=C–N moiety, whose general molecular formula (together with the numbering scheme and the optional R

1, R

2 substituents) is presented in

Figure 1, are useful precursors in the synthesis of various five-, six-, and seven-membered heterocycles [

1].

Over the past few decades, numerous studies have focused on the synthesis of amidrazones, their derivatives and metal complexes (all in the broadest possible meaning, i.e., involving organics, organometallics, coordination compounds, etc.), as well as on the determination of their biological properties, including antitumor, antimicrobial, antimalarial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, anticonvulsant and antinociceptive activities [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

In order to identify the present trends in scientific interest on the above class of chemicals, we have generated, using VOSViewer (version 1.6.20) software, a two-dimensional co-occurrence map, based on the frequency of the term “amidrazones”, with the examination of the 2825 terms, with 81 meeting the threshold of appearing at least five times (

Figure 2).

This analysis revealed five distinct clusters, highlighting trends in the research of these compounds, including synthesis and structural studies, methods of characterization, and biological activities (antibacterial, antimicrobial, and antitumor properties).

In particular, some authors have argued that various amidrazone derivatives and metal complexes exhibit significant antitumor properties against several cancer cell lines, including those of breast, colon, lung, and prostate cancers, as well as leukemia and epidermal carcinoma [

9,

10,

11].

Furthermore, antimicrobial properties of this group of compounds were also intensively studied. Thus, 1

H-pyrrole-2,5-dione derivatives, containing

N-bonded amidrazone substituents, were found to be active against

Enterococcus faecalis,

Escherichia coli,

Micrococcus luteus,

Mycobacterium smegmatis,

Nocardia corralina,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa,

Staphylococcus aureus, and

Yersinia enterocolitica bacteria [

13], whereas amidrazone amides of cyclohex-1-ene-1-carboxylic acid were active against the bacterial strains of

E. coli,

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

M. smegmatis,

S. aureus and

Y. enterocolitica, as well as the fungal strain of

Candida albicans [

16]. Moreover,

N1-2,4-dihydroxybenzenecarbothio-

N3-phenylacylamidrazones exhibited antifungal action against various dermatophytes, yeasts, and molds [

4], while 1-(piperidin-1-yl)-

N2-arylamidrazones exhibited both antibacterial (against

Bacillus subtilis,

E. coli,

P. aeruginosa, and

S. aureus) and antifungal (against

Aspergillus fumigatus and

C. albicans) properties [

7].

Then, an amidrazone-derived Au(III) complex demonstrated antibacterial activity against

B. subtilis and

S. aureus, as well as against a drug-resistant strain of

K. pneumoniae [

12]. In contrast, another amidrazone derivative and its Cu(II) complex had only low antibacterial activity, being also devoid of antifungal activity [

9]. Finally, the antibacterial properties of 85 amidrazones and various amidrazone-derived compounds against some Gram-positive bacteria (

E. faecalis,

M. luteus,

M. smegmatis,

N. corallina, and

S. aureus) were predicted using generalized linear models [

14].

In addition to this, the above-mentioned amidrazone-derived 1

H-pyrrole-2,5-diones and cyclohex-1-ene-1-carboxylic amides also possessed anti-inflammatory properties, related to the reduction in human peripheral-blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) proliferation, as well as to the inhibition of tumor necrosis factor TNF-α and IL-6, IL-10, and IL-1β pro-inflammatory cytokines production [

13,

16].

The illustration of the biological activity of amidrazones may be the fact that their best-known representative, called delpazolid (which contains the N–N=C–N moiety inside the alicyclic ring, which is different from open aliphatic chain molecules studied upon the present study) [

17], has a pharmacological action currently being studied in clinical trials in combination therapy for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis [

18]. Furthermore, other cyclic amidrazones are becoming increasingly popular in the design of new potential drugs [

19,

20].

In the present study, we have focused on the biological activity of seven amidrazones containing, as R

1 and R

2 substituents (

Figure 1), various aryl or heteroaryl rings (in the further part of the work marked as Ar

1 and Ar

2): phenyl, 4-methylphenyl, 4-nitrophenyl, 2-pyridyl, and 4-pyridyl. These compounds are herewith denoted as

2a–

2g, following the combination of Ar

1 and Ar

2 as shown in

Table 1 (the symbols

1a–

1g are reserved for the corresponding thioamides, from which the amidrazones were synthesized as shown in

Scheme 1.

It is a kind of paradox that, although

2a–

2g compounds were used by many authors [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33] as starting points for the preparation of some other, more advanced organic species often exhibiting their own biological activity, the concerned amidrazones themselves were not investigated from this viewpoint at all.

It is also important that, despite the fact that many amidrazones and their derivatives were already studied with respect to their antitumor, antimicrobial, antimalarial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, anticonvulsant and antinociceptive properties (as we have already explained), to the best of our knowledge there is no literature reference on the determination of their antioxidant activity or digestive tract enzymes inhibition.

Furthermore, some of the presently studied amidrazones (namely

2c–

2e and

2g) still do not have any synthesis characteristics at all, e.g., in the Reaxys database [

34]—and this lack also concerns basic information, such as their melting point.

Finally, the spectroscopic characterization of amidrazones 2a–2g is insufficient. For example, despite the relative simplicity of their molecules, these nitrogen-containing compounds have never been studied by 15N NMR; consequently, their 15N chemical shifts are unavailable.

Therefore, the main goal of the present work was the study of the biological activity of amidrazones 2a–2g that included the determination of the following: (1) antioxidant properties using two analytical assays (DPPH—2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl and FRAP—ferric-reducing antioxidant power); (2) inhibitory activity for three digestive tract enzymes: α-amylase, lipase, and pepsin; (3) cytotoxic activity; and (4) antibacterial and antifungal activity. Then, this wide study was followed by the chemometric multivariate analyses (PCA—principal component analysis and HCA—hierarchical cluster analysis). Moreover, Pearson correlations were calculated, and the color correlation matrix was generated to analyze the relationships among the evaluated biological properties of the synthesized compounds. Additionally, the 1H-15N HMBC-NMR spectra of 2a–2g were measured, yielding the 15N chemical shifts for the observable nitrogen atoms.

2. Results and Discussion

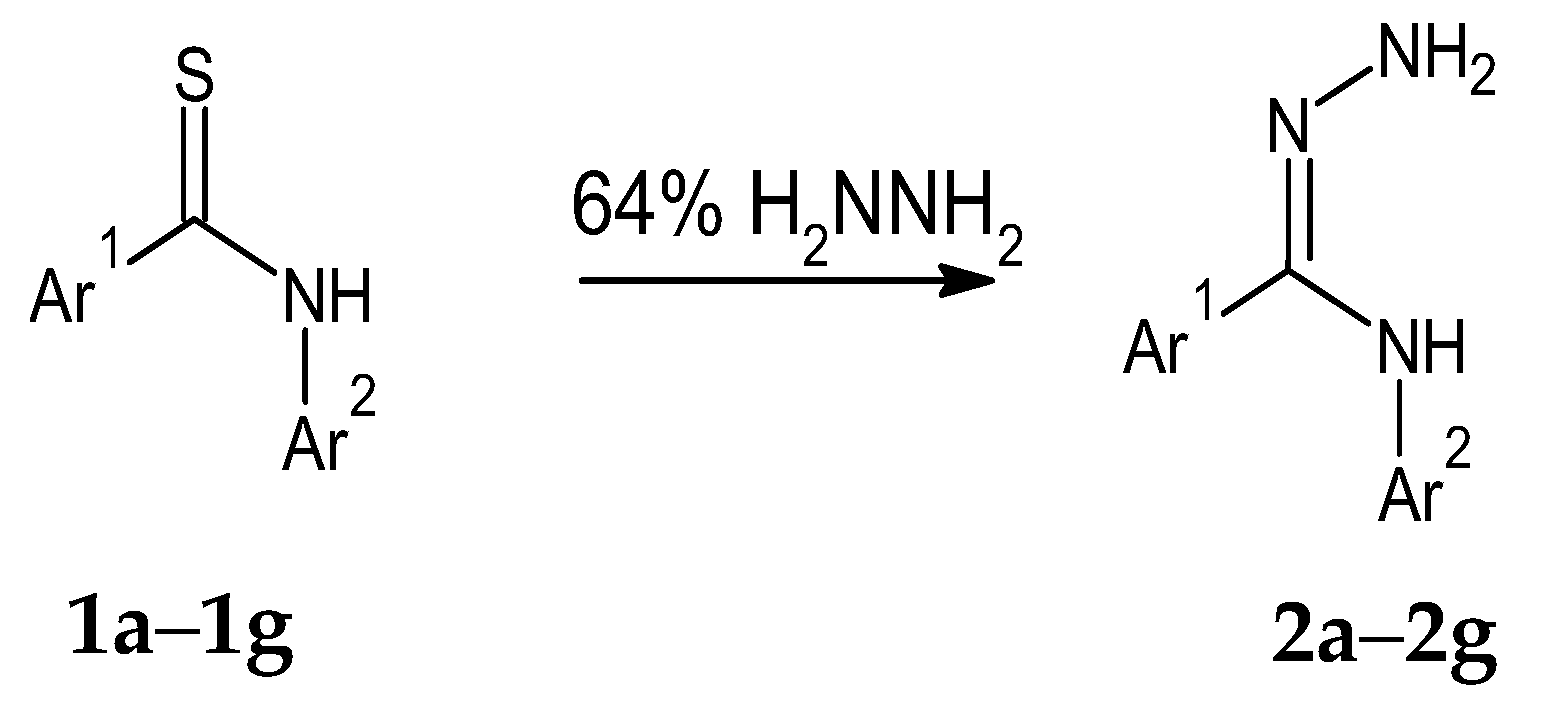

2.1. The Synthesis of Amidrazones 2a–2g

Amidrazones

2a–

2g were obtained by the modified Spassov method [

35] in the reactions of thioamides

1a–

1g with 64% hydrazine hydrate solution, as shown in

Scheme 1.

The modification of the synthesis involved the usage of a lower concentration of hydrazine hydrate (64% instead of 80%); thus, similar product yields were obtained upon the reduction in the reagents’ toxicity and costs.

2.2. NMR Study of Amidrazones 2a–2g

Amidrazones

2a–

2g were characterized by

1H,

13C,

1H-

13C HMQC,

1H-

13C HMBC, and

1H-

15N HMBC NMR spectra (in DMSO-d6), with the assignment of all signals. The

1H,

13C, and

15N chemical shifts are listed in

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4; the positions inside the Ar

1 and Ar

2 substituents are numbered as 1′…6′ and 1″…6″, respectively.

The

1H and

13C NMR signals for

2g were assigned in the same way as for

2a–

2f [

13], i.e., by

1H-

13C HMQC (one-bond correlations) and

1H-

13C HMBC (long-range correlations) methods. The

13C chemical shifts of

2g follow an analogous pattern as in the previously studied amidrazones: the values for C1′–C3′ are nearly identical to those in

2f (the same Ar

1 = 4-pyridyl substituent), while those for C1″–C4″ are similar to those in

2c (the same Ar

2 = 4-methylphenyl substituent). Then, the

13C chemical shifts for C2a in

2g and

2a–

2f are in the relatively narrow ca. 135–139 ppm range, their similarity reflecting the presence of the same >C= moiety.

The 15N signals were assigned based on the correlations in the 1H-15N HMBC spectra. They were usually observed at the distance of two (N2′H3′, N4′H3′, N2″H3″) and/or three (N2′H4′, N3H2″, NO2-H3″) bonds. For example, in the 1H-15N HMBC spectrum of the new 2g compound, the H3′ atom correlates with N4′ (two bonds distance: H3′-C3′-N4′), while the H2″ one correlates with N3 (three bonds distance: H2″-C2″-C1″-N3); moreover, from the viewpoint of both concerned hydrogens these are the only possible correlations (for any others, the distance to the nearest nitrogen(s) would exceed four bonds)—which unambiguously indicates N4′ and N3, respectively. Additionally, for 2b and 2e where, in contrast to 2a, 2c–2d, and 2f–2g, the H1 and H3 signals were much less broadened (indicating the lack of mobility of NH2 and NH protons, at least in the NMR time scale), the interactions over one bond were also observed (N1H1, i.e., inside the NH2 group; and N3H3, i.e., inside the NH group). Finally, the unprotonated N2 atom was never detected, most likely because of the too-long distance to the nearest protons in Ar1 and Ar2 substituents (four bonds to H2′ and five bonds to H2″).

The N3 signal in all

2a–

2g amidrazones appears in the ca. −302 to ca. −285 ppm range. These values are comparable to the

15N chemical shift for

N-methylaniline (containing the analogous Ph-NH-C moiety), which is 53.0 ppm (also in DMSO-d

6) as referenced to liquid ammonia, i.e., −328.7 ppm in respect to neat nitromethane [

36]; the relative shift of −381.7 ppm between liquid NH

3 and neat CH

3NO

2 was taken into account [

37].

The N3 chemical shift (δN3) is sensitive to the changes in Ar1 and/or Ar2 substituents. It can be especially exemplified by 2b–2e containing the same Ar1 = 2-pyridyl and different Ar2 substituents: the Ar2 = phenyl → Ar2 = 4-methylphenyl (2b → 2c) replacement results in a ca. 3 ppm decrease in δN3 (−296.3 ppm → −299.3 ppm), whereas the Ar2 = phenyl → Ar2 = 4-nitrophenyl or 2-pyridyl (2b → 2d or 2e) transition results in a ca. 9–11 ppm increase in δN3 (−296.3 ppm → −287.0 ppm or −285.0 ppm). This is understandable, as the former 15N shielding effect corresponds to the introduction of the electron-donating methyl group (4-CH3), while the latter 15N, a deshielding one, corresponds to the presence of the electron-withdrawing nitro group (4-NO2) or a heterocyclic nitrogen atom (in the 2-pyridyl moiety). A similar, although noticeably weaker N3 shielding phenomenon (δN3 decrease by 0.5 ppm: −301.2 ppm → −301.7 ppm) was related to the introduction of the electron-donating 4-CH3 side group into Ar2 (Ar2 = phenyl → Ar2 = 4-methylphenyl) upon the 2f → 2g replacement, i.e., when Ar1 = 4-pyridyl remained identical.

In contrast, the δN3 changes following variations inside Ar1 (Ar1 = phenyl → Ar2 = 2-pyridyl or 4-pyridyl), upon the same Ar2 = phenyl (thus, 2a → 2b or 2f), were less characteristic (−296.7 ppm → −296.3 ppm or −301.2 ppm, respectively), although both 2-pyridyl and 4-pyridyl substituents are electron-withdrawing. Most likely, the structural changes concerning Ar1 (bound to C2a) are simply less important from the viewpoint of the N3 atom than those occurring within Ar2 (bound just to N3); thus, the resulting shielding/deshielding effects at this nitrogen are of various signs and small absolute magnitude.

Then, for

2b–

2e and

2f–

2g, the N2′ or N4′ atoms (in Ar

1 = 2-pyridyl or 4-pyridyl) are present in the respective ranges from ca. −77 to ca. −74 ppm or from ca. −70 to ca. −69 ppm. These δ

N2′ and δ

N4′ values are generally similar to those for 2-methylpyridine and 4-methylpyridine (containing the same 2-Py-C or 4-Py-C moiety), which are 315.7 ppm and 303.4 ppm (both in DMSO-d

6), respectively, as referenced to liquid ammonia, i.e., −66.0 ppm and −78.3 ppm in respect to neat nitromethane [

36,

37]. However, for these Ar

1 substituents, the 2-pyridyl nitrogens are by ca. 4–8 ppm more shielded than the 4-pyridyl ones; as the best examples may serve the pairs of

2b and

2f (with the same Ar

2 = phenyl): δ

N2′ = −74.3 ppm vs. δ

N4′ = −69.4 ppm, as well as

2c and

2g (with the same Ar

2 = 4-methylphenyl): δ

N2′ = −76.9 ppm vs. δ

N4′ = −69.1 ppm. It is interesting that in the case of the presently studied amidrazones, such a relationship is opposite to that reported for simple methylpyridines (δ

N2′ = −66.0 ppm in 2-methylpyridine vs. δ

N4′ = −78.3 ppm in 4-methylpyridine); this is surprising but certain.

Finally, as it could be expected, the Ar2 changes (phenyl → 4-methylphenyl → 4-nitrophenyl → 2-pyridyl and phenyl → 4-methylphenyl, in the corresponding series of 2b → 2c → 2d → 2e and 2f → 2g) have rather negligible impact at the δN2′ and δN4′ chemical shifts (−74.3 ppm → −76.9 ppm → −74.4 ppm → −76.8 ppm and −69.4 ppm → −69.1 ppm, respectively), most likely owing to the large distance between N2′ and N4′ atoms from the N3-bonded Ar2 ring system.

In contrast, for 2e (the only species with 2-pyridyl as Ar2), the N2″ signal occurs at −108.9 ppm, which is ca. 30–35 ppm smaller than those of N2′ for 2b–2e (all with 2-pyridyl as Ar1); it is also ca. 43 ppm less than for 2-methylpyridine (δN2′ = −66.0 ppm). Such a strong deshielding of N2″ compared to N2′ in 2e (−108.9 ppm vs. −76.8 ppm) is probably caused by linking of the electron-acceptor -NH- group to Ar2, while Ar1 is carbon-bonded.

Finally, for

2d, the -NO

2 side group (in Ar

2 = 4-nitrophenyl) occurs at −8.8 ppm. This parameter is very close to that for nitrobenzene: −9.8 ppm, for 4-nitroaniline (i.e., 1-amino-4-nitrobenzene): −9.6 ppm, and for

N,

N-dimethyl-4-nitroaniline (i.e., 1-dimethylamino-4-nitrobenzene): −10.4 ppm (all in DMSO-d

6, the

15N chemical shifts referenced directly to neat nitromethane) [

38,

39,

40].

2.3. Biological Activity of Amidrazones 2a–2g

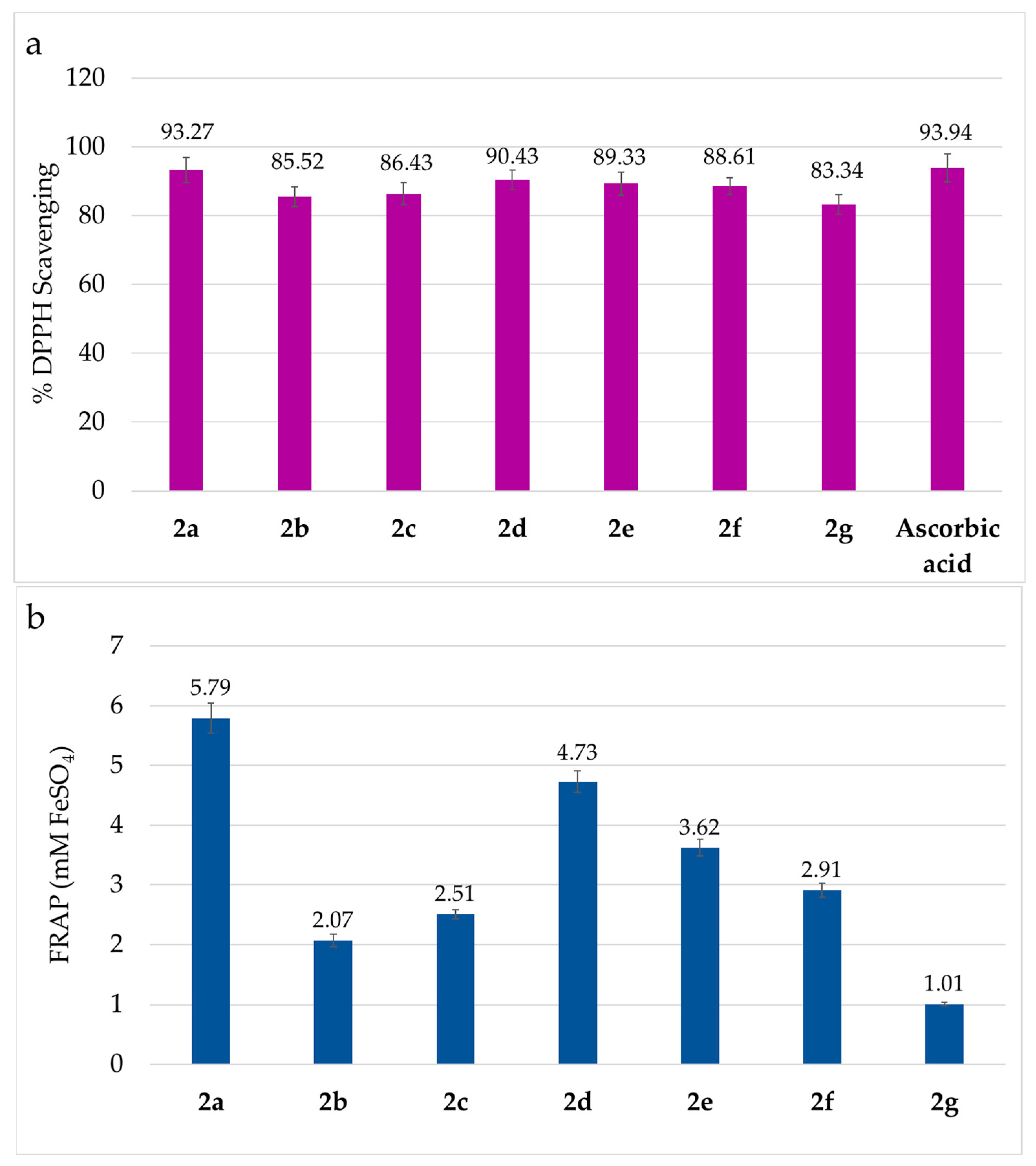

2.3.1. Antioxidant Activity of Amidrazones 2a–2g

The antioxidant activity of compounds

2a–

2g was determined using two spectrophotometric methods: the DPPH radical scavenging assay, which measures the ability of amidrazones to scavenge DPPH radicals, causing a discoloration of the DPPH solution; and the FRAP assay, which measures the reducing ability of these compounds by converting the colorless Fe

3+–TPTZ (2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine) complex into the intensely blue Fe

2+–TPTZ complex. The obtained DPPH and FRAP results are presented in

Figure 3a,b.

All amidrazones

2a–

2g showed high antioxidant potential, with the ability to inhibit free radicals from 83.34% to 93.27% in the DPPH assay (

Figure 3a), while the FRAP values ranged between 1.01 and 5.79 mM FeSO

4 (

Figure 3b).

The highest DPPH activity was exhibited by 2a (93.27%) and 2d (90.43%), being comparable to the reference ascorbic acid (93.94%). Interestingly, the same amidrazones demonstrated the highest FRAP results: 5.79 mM FeSO4 for 2a and 4.73 mM FeSO4 for 2d.

Generally, the order of antioxidant activity of compounds 2a–2g determined by the DPPH and FRAP methods is the same: 2a > 2d > 2e > 2f > 2c > 2b > 2g; therefore, the DPPH and FRAP results are consistent. Based on this, the influence of individual substituents present in amidrazone derivatives on their antioxidant properties can be observed. As already mentioned, a compound 2a, containing two phenyl rings, weak electron-donating substituents at Ar1 and Ar2 positions, had the highest antioxidant properties. However, the replacement of the phenyl group by 2-pyridyl (2a → 2b–2e) or 4-pyridyl (2a → 2f–2g) substituent at the Ar1 position decreased the antioxidant activity of amidrazones 2b–2g significantly (this is particularly visible in the FRAP results). This indicates that electron-withdrawing substituents at the Ar1 position reduce the antioxidant activity of the tested compounds. Meanwhile, for Ar2 position (when to compare amidrazones having the same Ar1) the replacement of phenyl group by electron-withdrawing substituents, such as 4-nitrophenyl (2b → 2d) or 2-pyridyl (2b → 2e), enhanced antioxidant activity (both examples upon Ar1 = 2-pyridyl), whereas the impact of analogous phenyl → 4-methylphenyl (the electron-donating group) transition is more variable, including either enhancement (2b → 2c, upon Ar1 = 2-pyridyl) or weakening (2f → 2g, upon Ar1 = 4-pyridyl) of antioxidant properties.

The DPPH and/or FRAP methods have already been used to determine the antioxidant properties of many organic compounds, including nitrogen-containing species, such as vanillin-derived amines [

41] and sinaptic acid anilides [

42]. It confirms their usefulness in the research on the biological activity of compounds of natural and synthetic origin. However, as mentioned, the DPPH and FRAP methods have never been applied to analogous studies of amidrazones.

2.3.2. Inhibitory Activity of Amidrazones 2a–2g Against Enzymes

The inhibitory activity of compounds

2a–

2g was tested against three digestive tract enzymes: α-amylase, lipase, and pepsin, and the obtained results are presented in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

Amidrazones

2a–

2g exhibited α-amylase inhibition in a range of approximately 28.6–86.8%, with activity increasing with concentration (

Figure 4).

Figure 4.

α-amylase-inhibition activity of amidrazones 2a–2g. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Figure 4.

α-amylase-inhibition activity of amidrazones 2a–2g. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

In the case of the highest amidrazones concentration (1 mg/mL), the α-amylase inhibition rate was within a 70.7–86.8% range, being the strongest for

2d: 86.8% (which is similar to a reference drug acarbose [

43] at the 20 mg/mL dose: 88.3%). It is worth noting that all compounds at a concentration of 1 mg/mL showed an inhibition rate above 70%. However, derivatives

2e–

2g exhibited relatively high inhibiting activity also at medium concentrations of 0.6–0.8 mg/mL (e.g., >75% at 0.8 mg/mL). This suggests that substituents, such as a 4-pyridine ring in the Ar

1 position (

2f–

2g) or two 2-pyridine rings (

2e), may also have a beneficial effect on α-amylase inhibitory activity.

Moreover, the synthesized amidrazones

2a–

2g inhibited lipase activity by 28.0–60.0% (

Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Lipase-inhibition activity of amidrazones 2a–2g. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Figure 5.

Lipase-inhibition activity of amidrazones 2a–2g. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

It is noteworthy that the lipase inhibition rate was in the 49.0–60.0% range for the highest concentration (1 mg/mL) of the synthesized compounds, being the strongest for

2a–

2c: 57.0–60.0% (which is ca. 0.1 times lower than for a reference drug orlistat [

44] at the 20 mg/mL dose: 67.0%).

Finally, compounds

2a–

2g exhibited pepsin inhibition in a range of approximately 34.1–76.6%, with activity increasing with concentration (

Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Pepsin-inhibition activity of amidrazones 2a–2g. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Figure 6.

Pepsin-inhibition activity of amidrazones 2a–2g. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

As can be seen, for the highest concentration (1 mg/mL) of amidrazones, the pepsin inhibition rate was in the 66.9–76.6% range, being the strongest for

2c: 76.6% (which is close to a reference drug, sucralfate [

45] at the 20 mg/mL dose: 77.4%). However, all compounds at a concentration of 1 mg/mL, except

2g, with 4-pyridyl and 4-methylphenyl as Ar

1 and Ar

2 substituents, showed an inhibition rate above 70%.

In summary, all amidrazones 2a–2g revealed dose-dependent inhibitory effects on the three gastrointestinal enzymes: α-amylase, lipase, and pepsin. Some of them, applied at a dose of 1 mg/mL, exhibited inhibition activities comparable to those of the reference drugs acarbose, orlistat, and sucralfate (used at a twenty-fold higher dose of 20 mg/mL). Among all the synthesized amidrazones, compound 2d containing 2-pyridyl and 4-nitrophenyl in Ar1 and Ar2 positions, respectively, stood out in particular, with the highest α-amylase inhibition at the highest concentration (1 mg/mL) and lipase and pepsin inhibition at the lowest concentration (0.2 mg/mL).

To the best of our knowledge, no reports on the impact of amidrazones on lipase, pepsin, and amylase inhibitory activity have been published to date. However, analogous effects were reported for a few different enzymes, but in the case of some other amidrazones (not those of

2a–

2g) and also their derivatives. In particular, some amidrazones were capable of inactivating soybean lipoxygenase-1 [

46]. Moreover, several compounds containing the amidrazone moiety were described as acetylcholinesterase (AChE) or butyrylocholinesterase (BChE) inhibitors (potentially valuable for Alzheimer’s disease treatment) [

47,

48], while a few others showed the ability to inhibit furins, trypsin, and thrombin [

49,

50].

Thus, the present data, combined with the reports of previous authors, indicate the possibility of using amidrazones and their derivatives to inhibit various enzymatic processes.

2.3.3. Cytotoxic Activity of Amidrazones 2a–2g

To determine the cytotoxicity of amidrazones

2a–

2g, a hemolysis test was performed. Hemolysis is the rupture of red blood cells (erythrocytes), indicating cytotoxic effects on these cells [

51]. Triton X-100 [

52] (1 mg/mL), used as a reference, caused 91.6% hemolysis.

The percentage of hemolysis of amidrazones

2a–

2g, depending on the concentration used, is illustrated in

Figure 7.

The most potent cytotoxic activity was observed for two amidrazones at the highest concentration (1 mg/mL), i.e., 2b and 2d (17.4% and 16.5%, respectively), which featured a 2-pyridyl group in the Ar1 position and phenyl and 4-nitrophenyl groups, respectively, in the Ar2 position. However, at this concentration, other investigated amidrazones were able to rupture erythrocytes, with a range of 10.3% to 13.4%. Importantly, all amidrazones at the lower concentrations of 0.2–0.4 mg/mL exhibited low cytotoxicity (1.0–6.1%).

To the best of our knowledge, the hemolytic activity of amidrazones has not been previously studied. Among compounds containing a hydrazine moiety (which is a part of the amidrazone system), phenylhydrazine showed several times higher hemolytic activity (ca. 40.5%), at ca. 0.6–0.7 mg/mL concentrations [

53].

2.3.4. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity of Amidrazones 2a–2g

The disk diffusion method was used to qualitatively test the antimicrobial activity of seven amidrazone derivatives

2a–

2g against five Gram-positive bacterial strains (

S. aureus,

M. luteus,

E. faecalis,

M. smegmatis, and

G. rubripertincta) and four Gram-negative bacterial strains (

E. coli,

Y. enterocolitica,

K. pneumoniae, and

P. aeruginosa), as well as a

C. albicans fungal strain. To determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of each synthesized compound, the broth microdilution method was employed. The results of the antimicrobial activity test for the amidrazone derivatives are presented in

Table 5.

The strongest antibacterial activity against all Gram-positive bacterial strains was exhibited by 2d, which features 2-pyridyl and 4-nitrophenyl groups in the Ar1 and Ar2 positions, respectively. The MIC values were 64 µg/mL for S. aureus and G. rubripertincta, as well as 128 mg/mL for M. luteus, E. faecalis, and M. smegmatis. However, the same amidrazone 2d was less effective against Gram-negative bacterial strains, and, unfortunately, showed no inhibitory effect on the Gram-negative bacterium P. aeruginosa (MIC > 512 µg/mL). On the contrary, the compound 2d revealed the best antifungal activity with an MIC parameter against C. albicans of 32 µg/mL, i.e., 4 to 8 times less than for all other compounds (MIC = 128–256 µg/mL).

The least favorable substituent arrangement with respect to antimicrobial activity was the presence of two 2-pyridyl rings (2e) or the 2-pyridyl and phenyl ones (2b), their MIC values being at least 256 µg/mL. Then, the antimicrobial activity of 2b and 2d (both with the same Ar1 = 2-pyridyl substituent) was significantly enhanced upon the introduction of the 4-NO2 side group into the Ar2 phenyl ring, as indicated by the respective MIC decreases (256 or 512 µg/mL → 64 µg/mL for S. aureus and G. rubripertincta; 256 µg/mL → 32 µg/mL for C. albicans).

In our previous and the most recent papers, we described the antibacterial properties of some acyl, pyrrole-2,5-dione, and 1,2,4-triazole derivatives, obtained in the reactions of amidrazones

2a–

2g with cyclic anhydrides. These compounds exhibited variable activity (in general, their MIC values were in the 64–512 µg/mL range), being usually more active against Gram-positive than Gram-negative bacterial strains [

13,

16,

33,

54].

Then, we also reported the antifungal properties of some acyl derivatives, formed in the reactions of amidrazones

2a–

2g with maleic anhydride [

54] or 3,4,5,6-tetrahydrophthalic anhydride [

16], their MIC values being 256–512 mg/mL against

C. albicans. Thus, all the presently studied

2a–

2g compounds exhibit significantly higher antifungal activity, which indicates a larger potential of amidrazones possessing the unsubstituted hydrazine group.

Additionally, atomic force microscopy (AFM) was used to visualize the effect of the most potent amidrazone

2d on the cell walls of representative bacterial strains, such as

S. aureus and

M. smegmatis, as well as the yeast strain

C. albicans (

Figure 8). This method is particularly useful because it allows for imaging and measurement of the mechanical properties of living cells under physiological conditions [

55].

In the present case, bacterial and fungal strains were grown in the presence of 2d at a concentration twice lower than the respective MIC value. The AFM analysis revealed that treatment with this amidrazone for 12 h induced some morphological changes in the bacterial walls of M. smegmatis and C. albicans, resulting in an increased surface roughness of the cells (1.25-fold and 1.14-fold, respectively). The surface roughness of the cell was calculated using the root mean square (RMS) value, which represents the standard deviation of the height distribution within a 1 × 1 μm2 image area. The increase in the numerical surface roughness suggests the efficiency of 2d in interacting with the cellular membrane.

In particular, the exposure of C. albicans cells to 2d led to slight irregularities on the cell surface and the release of small vesicles, whereas the surface of the control cells, having a smooth surface regular shape, was covered with small, uniform grains.

Then, the surface of M. smegmatis cells treated with 2d was less smooth than that of the control cells (the culture without the addition of 2d); numerous irregularities and protrusions were noticeable.

Finally, 2d only slightly affected the shape of S. aureus cells and the roughness of their surface (RMS = 1.02), which was relatively smooth and contained no pores or cracks, thus being almost indistinguishable from the control cells.

2.4. Chemometric Analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA), as representatives of unsupervised methods, were employed to assess similarities/dissimilarities between seven amidrazones 2a–2g differing in the Ar1 and Ar2 substituents, as well as to project them in a two-dimensional factor plane based on their biological activities including antioxidant, enzymes inhibition, cytotoxic, and antimicrobial (antibacterial and antifungal) properties.

2.4.1. Principal Component Analysis

The PCA was utilized to compare seven amidrazones

2a–

2g based on their biological parameters, and to find the relationships between all investigated biological descriptors (antioxidant activity determined by DPPH and FRAP methods, α-amylase, lipase, and pepsin inhibition, cytotoxic activity, and antibacterial and antifungal activity). The maximum number of principal components (PCs) was set at six of the thirty-two PCs, which gave eigenvalues greater than 1.00 (9.68, 7.92, 5.44, 4.28, 2.50, 2.19). However, the first two components contributed 54.99% of the total variation for the thirty-two characters under study. Therefore, only the first two PCs were used to understand the similarities or dissimilarities of the seven amidrazones

2a–

2g as illustrated in the score plot in

Figure 9a. Consequently, the relationships between the first two principal components and the studied variables were presented graphically by the loading plot in

Figure 9b.

The PC1 was positively correlated with antioxidant activity determined by DPPH (0.5315) or FRAP (0.5788) methods, and with lipase and pepsin inhibitory activity (0.5033–0.8011 and 0.3918–0.7423, respectively) at amidrazone concentrations (0.2–0.8 mg/mL), while negatively correlated with antimicrobial activity against the four Gram-positive bacterial strains (S. aureus, M. luteus, E. faecalis, M. smegmatis), fungal strain (C. albicans) (−0.6999 to −0.9073), and with α-amylase inhibition (−0.6672 and −0.8521) at low amidrazone concentrations (0.2–0.4 mg/mL).

The PC2 was positively correlated with lipase inhibition (0.9757) at the highest concentration (1 mg/mL) of the studied compounds and antibacterial activity against K. pneumoniae (0.5160). However, PC2 inversely contributed to antibacterial activity against the Gram-negative strain of P. aeruginosa (−0.6638), cytotoxic activity (−0.6998 to −0.9679) at moderate concentrations (0.4–0.8 mg/mL), and α-amylase inhibition (−0.7307 to −0.9125) at higher amidrazone concentrations (0.6–1 mg/mL).

As can be seen in

Figure 9, compounds

2b,

2c,

2e, and

2g (with low antimicrobial and antioxidant activity, high cytotoxic activity, high α-amylase inhibition at low concentrations, and low lipase and pepsin inhibitions) were located to the left in the score plot having negative values for PC1, while the

2a,

2d and

2f ones (with high antimicrobial and antioxidant activity, low cytotoxic activity, low α-amylase inhibition at large concentrations, and high lipase and pepsin inhibitions) were situated to the right in the diagram having positive values for PC1. Then, compounds

2a,

2b, and

2c with low activity against Gram-negative bacteria (

E. coli,

Y. enterocolitica,

K. pneumoniae,

P. aeruginosa), low cytotoxic activity, and low α-amylase inhibition were located above the A1 axis, whereas

2d,

2e,

2f, and

2g derivatives with high cytotoxic activity and high α-amylase inhibition were identified under the A1 axis.

It is noteworthy that amidrazones

2a–

2g fell into three distinct groups (

Figure 9). Three compounds (

2b,

2c, and

2a) with low antibacterial activity, cytotoxicity, and α-amylase inhibition, moderate antifungal efficiency, and high lipase inhibition created an evidently distinct cluster. However, with the highest antioxidant potential (DPPH = 93.27% and FRAP = 5.79 mM),

2a was distinct from

2b and

2c, although these three amidrazones were generally close to one another. Furthermore, another group of three compounds

2e,

2f, and

2g with low antioxidant properties (DPPH = 83.34–89.33%, FRAP = 1.01–3.62 mM) and cytotoxic activity (10.3–12.4%) at the highest concentration (1 mg/mL), high α-amylase inhibition (32.4–83.3%), and moderate lipase (29.0–53.0%) and pepsin (36.8–73.6%) inhibition was clearly separated on the score plot. Interestingly,

2f with the lowest cytotoxic activity (10.3%) was located some distance away from

2e and

2g. Finally,

2d with the longest distance from all other amidrazones revealed the highest antibacterial and antifungal activity (as already mentioned in

Section 2.3.4), high antioxidant potential and α-amylase inhibition at the highest concentration (1 mg/mL), and high lipase and pepsin inhibition at low concentrations. The reason for its different characteristics may be the presence of the -NO

2 side group in the Ar

2 substituent.

2.4.2. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis

The HCA was applied for the same reason as PCA, to group the synthesized amidrazones per their similarities and discrepancies based on the thirty-two investigated biological variables. The results obtained following HCA were presented as dendrograms (

Figure 10), in which two well-defined clusters of seven compounds (

Figure 10a) and two clusters of variable sets were visible (

Figure 10b).

The first cluster included an inter-cluster of

2a,

2g, and

2c, whereas

2b,

2f, and

2e were arranged in the second inter-cluster. The inter-cluster, including

2a,

2g, and

2c, was quite separated, because these compounds had the same moderate antifungal activity, low antibacterial and cytotoxic activity, and similar lipase and pepsin inhibitions. However,

2a and

2g, with insignificant differences in lipase inhibition, as well as the highest and lowest antioxidant properties (DPPH = 93.27% and 83.34%, respectively; FRAP = 5.79 mM and 1.01 mM, respectively), formed the sub-cluster. On the other hand, clustered compounds

2b and

2f exhibited the same low antimicrobial activity against Gram-negative bacteria, cytotoxicity, and high lipase inhibition at the lowest concentration (0.2 mg/mL). Meanwhile,

2e and

2f had similar DPPH values (89.33 and 88.61%, respectively) and enzyme inhibitions (α-amylase: 44.2–80.0% and 32.4–83.3%; lipase: 31.0–50.0% and 35.0–53.0%; pepsin: 38.8–73.2% and 38.3–73.6%). Additionally, the dendrogram presented in

Figure 10a clearly separated amidrazone

2d, which revealed the highest antimicrobial effect against Gram-positive and fungal strains, as well as high antioxidant activity, cytotoxicity, lipase and pepsin inhibitory activity at low concentrations, and α-amylase inhibition at the highest concentration.

Furthermore, HCA was utilized to group the thirty-two variables with common characteristics into clusters. A cluster composed of antioxidant potential, inhibition of three enzymes, and cytotoxic activity of the investigated compounds was clearly discernible, whereas their antibacterial and antifungal features formed the second cluster (

Figure 10b). Meanwhile, the first group, exhibiting antioxidant capacity, enzyme inhibition, and cytotoxic activity, underwent further subdivision into two sub-groups, including the following: (I) DPPH; α-amylase, pepsin, and lipase inhibitory activity; and (II) FRAP and cytotoxicity at different concentrations of the investigated compounds. This can be explained by the fact that the antioxidant potential affected the efficiency of enzyme inhibition. However, the second cluster was classified into two sub-groups, consisting of inhibitory effect against (I) three Gram-positive bacteria strains (

S. aureus,

E. faecalis,

M. smegmatis) and three Gram-negative bacteria strains (

E. coli,

K. pneumoniae,

P. aeruginosa), as well as (II) two Gram-positive bacteria strains (

M. luteus,

G. rubripertincta), one Gram-negative bacteria strain (

Y. enterocolitica), and the only fungal strain (

C. albicans). The formation of inter-clusters indicates high relationships between these variables (color matrix presented in

Figure 11).

The unsupervised methods, PCA and HCA, revealed that amidrazone

2d bearing two electron-withdrawing substituents at Ar

1 and Ar

2 (2-pyridyl and 4-nitrophenyl), which is well-separated from the other synthesized derivatives, exhibited high antimicrobial, antioxidant, cytotoxic, and enzyme inhibitory activity. Apparently, replacing the 4-nitrophenyl substituent with a moderate electron-withdrawing 2-pyridyl at the Ar

2 position in compound

2e resulted in a slight decrease in its biological properties and a longer distance from the inter-cluster in the HCA dendrogram (

Figure 10a). However, two electron-donating phenyl groups at positions Ar

1 and Ar

2 in compound

2a, situated on the upper right quarter of the score plot (

Figure 9a), were involved in the most effective scavenging of DPPH radicals and reduction in Fe(III)-TPTZ complex.

The PCA and HCA results together have shown that the analytical methods used to determine the biological properties of the synthesized amidrazone derivatives are different. In addition, the clustering behavior of these compounds appears to distinguish between the HCA and the PCA visualizations. Probably, the HCA may capture biological similarities more efficiently from a visual perspective than PCA because only the first two PCs, PC1 and PC2, are used on the score and loading plots.

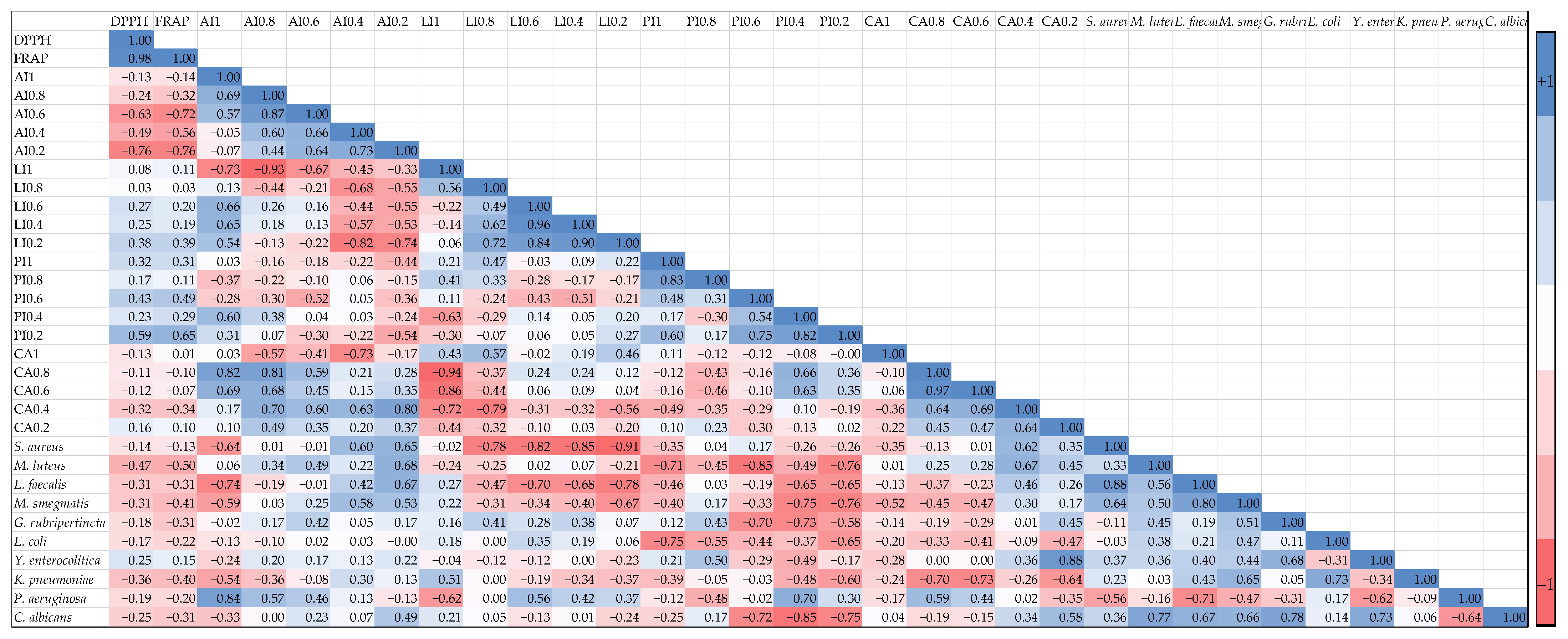

2.4.3. Correlation Analysis

In order to evaluate the strength and direction of the relationships among multiple variables, such as antioxidant properties, inhibitory activity against three enzymes, antibacterial, antifungal, and cytotoxic activities of seven amidrazones

2a–

2g, Pearson correlation analysis was carried out, with the obtained correlation coefficients being visualized on the color matrix (

Figure 11).

As illustrated in

Figure 11, correlation coefficients ranged from +1 (dark blue color) to −1 (dark red color), where positive values indicate a direct relationship and negative values indicate an inverse relationship. Expectantly, the color matrix illustrated significant positive relationship (r = 0.98) between the antioxidant activity measured by DPPH and FRAP assays. This high value of correlation coefficient confirms that, at the same time, all investigated amidrazones were capable of scavenging DPPH radicals and reducing (Fe

3+-TPTZ) to an intense blue color (Fe

2+-TPTZ) complex. The Pearson analysis also revealed strong negative correlations (r = −0.49 to −0.76) between antioxidant activity determined by DPPH and FRAP methods and α-amylase inhibition at low amidrazone concentrations (0.2–0.6 mg/mL), whereas DPPH and FRAP were positively correlated (r = 0.59–0.65) with pepsin inhibition at the lowest concentration of the studied derivatives, suggesting that enzyme inhibition was linked to their antioxidant activity. Meanwhile, positive correlations were observed between cytotoxic activity (r = 0.45–0.97) and enzyme inhibition (r = 0.31–0.96) at the increased concentrations. This indicates that a higher concentration of each amidrazone caused stronger cytotoxic and enzyme inhibition effects. Interestingly, lipase inhibition at low amidrazone concentrations positively correlated (r = 0.54–0.66) with α-amylase inhibition at the highest concentration, while negative associations (r = −0.33 to −0.82) were observed between inhibition potential of derivatives at 0.2 and 0.4 mg/mL against lipase and α-amylase. Moreover, positive correlation coefficients were found between the inhibition of α-amylase by amidrazones at low concentrations and the growth of four Gram-positive bacteria (r = 0.42–0.68) and cytotoxic activity (r = 0.35–0.81). On the contrary, pepsin inhibition at low amidrazone concentrations inversely correlated (r = −0.33 to −0.85) with the concerned bacterial and fungal strains (except

S. aureus,

Y. enterocolitica, and

P. aeruginosa). However,

S. aureus and

E. faecalis had strong negative correlations (r = −0.47 to −0.91) with lipase inhibition. Depending on concentrations, the discussed compounds could inhibit these bacterial strains, but did not exhibit pepsin and lipase inhibition. Most notably, positive correlations between Gram-positive bacteria strains were observed (r = 0.33–0.88). Moreover, positive linear associations were found between each Gram-positive bacterial strain and antifungal efficacy (r = 0.36–0.78). These correlation coefficients suggest that the investigated amidrazones had a similar trend for

S. aureus,

M. luteus,

E. faecalis,

M. smegmatis,

G. rubripertincta, and

C. albicans. In contrast, the Gram-negative bacterium

P. aeruginosa revealed moderate negative relationships with two Gram-positive bacteria,

S. aureus (r = −0.56) and

E. faecalis (r = −0.71), as well as with the Gram-negative bacterium

Y. enterocolitica O3 (r = −0.62) and the fungus

C. albicans (r = −0.64). Therefore, the compounds with antimicrobial activity against

P. aeruginosa caused no activity against

S. aureus,

E. faecalis, and

C. albicans.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Information

Reagents and solvents were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich or Avantor Performance Materials Poland. Melting points were measured using a Mel-Temp apparatus (Electrothermal, Stone, UK). 1H and 13C NMR spectra (including 1H-13C HMQC and HMBC) as well as 1H-15N HMBC-NMR spectra were recorded in DMSO-d6 at 295–300 K by Bruker Avance III 400 MHz or Bruker Avance III 700 MHz NMR spectrometers (Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). The 1H and 13C chemical shifts were referenced to TMS, with residual 1H and 13C solvent signals as primary references (DMSO-d6: 2.50 ppm and 40.0 ppm, respectively), whereas the 15N chemical shifts were referenced to external neat nitromethane. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were performed on a Synapt G2-Si mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). The course of reactions was monitored using TLC chromatography (silica gel on TLC-PET foils, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

3.2. Synthesis of Amidrazones 2a–2g

Thioamides

1a–

1g were obtained according to the previously described methods:

1a [

56],

1b–

1d [

57],

1e [

58],

1f–

1g [

59]. Amidrazones

2a–

2g were obtained by the modified Spassov method [

35] in the reactions of 0.01 mol of thioamides

1a–

1g with an excess of 64% hydrazine hydrate solution (0.02–0.10 mol). Unless otherwise stated below, the reaction was carried out at room temperature for 24 h (except for compounds

2c–

2e), then 20 mL of water was added. The resulting precipitate was filtered off and washed with water, followed by purification by crystallization (except for

2c).

For 2a, 2.13 g (0.01 mol) of N-phenylbenzenecarbothioamide 1a was dissolved in 5 mL of anhydrous ethanol with gentle heating, then 1 mL (0.02 mol) of 64% hydrazine was added. After 24 h, 20 mL of water was added. After 5 min, obtained precipitate was filtered off and recrystallized from 10 mL of ethanol. After adding 30 mL of water to the crystallizer, a pinkish crystalline precipitate was formed, which was filtered off. Yield 46.97%, m.p. 86–88 °C. HR-MS m/z: 212.1184 [M+ + 1] (calculated for 212.1188: C13H14N3).

For 2b, 2.14 g (0.01 mol) of N-phenylpyridine-2-carbothioamide 1b was mixed with 5 mL (0.1 mol) of 64% hydrazine. After 24 h, 20 mL of water was added, the precipitate filtered off, and recrystallized from methanol. Yield 47.41%, m.p. 109–112 °C. HR-MS m/z: 213.1136 [M+ + 1] (calculated for 213.1140: C12H13N4).

For 2c, 2.28 g (0.01 mol) of N-(4-methylphenyl)pyridine-2-carbothioamide 1c was mixed with 1.5 mL (0.03 mol) 64% hydrazine. The solution was left for 3 days at room temperature. Then 20 mL of water was added, and the precipitate was filtered off. The crude solid was dissolved in 20 mL of methanol, and the insoluble precipitate was filtered off and discarded. Then water was gradually added to the methanol solution, the solution was decanted from the precipitate, and water was added again. The operation was repeated as long as a precipitate was formed. Fractions with a melting point below 74 °C were purified in this way again. Yield 30.16%, m.p. 75–78 °C. HR-MS m/z: 227.1290 [M+ + 1] (calculated for 227.1297: C13H15N4).

For 2d, 2.59 g (0.01 mol) N-(4-nitrophenyl)pyridine-2-carbothioamide 1d was mixed with 10 mL 96% ethanol and 6 mL (0.12 mol) 64% hydrazine. It was heated lightly for 1–2 min until the precipitate was dissolved, then left at room temperature. After 1 h, 20 mL of water was added to the mixture. The obtained light yellow precipitate was filtered off and recrystallized from ethanol. Yield 52.32%, m.p. 174–177 °C. HR-MS m/z: 258.0986 [M+ + 1] (calculated for 258.0991: C12H12N5O2).

For 2e, 2.15 g (0.01 mol) of N-(pyridin-2-yl)pyridine-2-carbothioamide 1e was mixed with 3 mL (0.06 mol) of 64% hydrazine. After 24 h, 20 mL of water was added. The precipitate was filtered and recrystallized from 50 mL of water with the addition of about 2.5 g of activated carbon (about 20 min of heating). Yield 47.47%, m.p. 107–110 °C. HR-MS m/z: 214.1086 [M+ + 1] (calculated for 214.1093: C11H12N5).

For 2f, 2.14 g (0.01 mol) of N-phenylpyridine-4-carbothioamide 1f was mixed with 5 mL (0.1 mol) of 64% hydrazine. After 24 h, 20 mL of water was added. The obtained precipitate was filtered off and purified by crystallization from a mixture of water and methanol (1:1). Yield 56.06%, m.p. 125–128 °C. HR-MS m/z: 213.1136 [M+ + 1] (calculated for 213.1140: C12H13N4).

For 2g, 2.28 g (0.01 mol) of N-(4-methylphenyl)pyridine-4-carbothioamide 1g was mixed with 5 mL (0.1 mol) of 64% hydrazine. After 24 h, 20 mL of water was added. The obtained precipitate was filtered off and purified by crystallization from a mixture of water and methanol (1:1). Yield 33.61%, m.p. 127–129 °C. HR-MS m/z: 227.1295 [M+ + 1] (calculated for 227.1297: C13H15N4).

3.3. Antioxidant Activity of the Synthesized Amidrazones 2a–2g

Antioxidant activity of 2a–2g was tested using two alternative analytical methods: DPPH and FRAP.

3.3.1. DPPH Assay

This method involves a reduction of the stable, purple-colored 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical in the reaction with a given antioxidant [

60]. The DPPH solution was prepared by dissolving 7.89 mg of DPPH in 100 mL of 99.5% ethanol and stored in darkness for 2 h. Then, 800 µL of Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) was mixed with 1000 µL of DPPH solution in an Eppendorf tube, followed by the addition of 200 µL of the

2a–

2g sample (1 mg/mL). The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, and absorbance was measured at 517 nm. A blank was prepared using 1200 µL of ethanol and 800 µL of Tris-HCl buffer. The percentage of DPPH radical scavenging activity was calculated using the formula:

3.3.2. FRAP Assay

The FRAP assay evaluates antioxidant capacity by measuring reduction in the ferric Fe

3+-TPTZ complex to the respective ferrous Fe

2+-TPTZ species (TPTZ being 2,4,6-tris(pyrid-2-yl)-1,3,5-triazine), which results in a navy blue color [

60]. To prepare the reagents, sodium acetate trihydrate (3.1 g) was dissolved and combined with 16 mL glacial acetic acid to make an acetic acid buffer (pH 3.6). Separately, 0.0256 g of TPTZ was dissolved in 4 mL of 40 mM HCl, and 0.276 g of FeCl

3·6H

2O was dissolved in water, then diluted to 50 mL. The FRAP working solution was prepared by mixing the acetic acid buffer and the FeCl

3-TPTZ solutions in a 10:1 ratio, then the solution was incubated at 37 °C. For the assay, 50 µL of FRAP working solution was mixed with 950 µL of the

2a–

2g working solutions (obtaining final concentrations of amidrazones

2a–

2g of 4 mM), incubated in darkness at 37 °C for 15 min, and absorbance was measured at 593 nm. FeSO

4 served as the standard, and distilled water was used as the blank. The antioxidant capacity was calculated using the formula:

3.4. Enzymes Inhibitory Activity of the Synthesized Amidrazones 2a–2g

3.4.1. α-Amylase Inhibition

The α-Amylase inhibitory assay was determined by the Sundaram method [

61]. Briefly, 250 µL of

2a–

2g solution was placed in a tube, and then 250 µL of 0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer with pH 6.9 and α-amylase solution (0.5 mg/mL) were added. The mixture was incubated for 10 min at 25 °C, then 250 µL of 1% starch solution as substrate (prepared in 0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer with pH 6.9) was added, and then further incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. By adding 500 µL of dinitrosalicylic acid, the reaction was terminated. Finally, each reaction mixture was diluted with 5 mL of water, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm. The control was free DMSO. The α-amylase inhibitory activity was calculated as a percentage inhibition:

3.4.2. Lipase Inhibition

The lipase inhibitory assay was determined by the Sikander method [

62]. The assay is based on a change in pH from neutral to acidic after lipase activity, which changes the color of the medium. Plates were prepared by using the medium composed of 2% agar (

w/

v) along with 2.5% (

v/

v) olive oil and 1% (

w/

v) phenol red as an indicator. Lipase solution was prepared in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (30 mg/mL). After this, 60 μL of the master mix was prepared using 30 μL of lipase solution and 30 μL of

2a–

2g sample solutions and poured into wells (obtaining final concentrations of 0.2 mg/mL, 0.4 mg/mL, 0.6 mg/mL, 0.8 mg/mL, and 1 mg/mL). The control well contained 30 μL of lipase and buffer. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the change in color in the control (a yellow zone around the well of a red background due to acidic pH) indicated the activity of lipase. Lipase inhibitory activity was calculated as percentage inhibition:

3.4.3. Pepsin Inhibition

The pepsin inhibitory assay was determined by the Mushtaq method [

63]. Briefly, 100 µL of

2a–

2g solution was mixed with 100 µL of pepsin solution (5 mg in 0.01 M HCl) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min to allow for enzyme activity. Then, 200 µL of albumin solution (5 mg/mL) was added as a substrate, and the mixture was further incubated for 20 min. To stop the reaction, 1600 µL of biuret reagent was added. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm. Sucralfate and DMSO were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Pepsin inhibitory activity was calculated using the formula:

3.5. Cytotoxic Activity of the Synthesized Amidrazones 2a–2g

The cytotoxicity of

2a–

2g was determined by examination of the level of erythrocyte hemolysis using the Maqsood method [

64]. The

2a–

2g compounds were dissolved in DMSO. Fresh blood (5 mL) was centrifuged, and red blood cells were washed with phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Then, 20 µL of the

2a–

2g sample was mixed with 180 µL of diluted blood cell suspension and incubated at 37 °C for 35 min, with shaking after 10 min. Following incubation, the mixture was chilled on ice, centrifuged, and 100 µL of the supernatant was diluted with 900 µL PBS. From each tube, 200 µL was transferred to an ELISA plate. Triton X-100 (0.1%) served as the positive control, and PBS as the negative control. Absorbance was measured at 576 nm using an ELISA reader (Elx 800, BioTek, San Diego, CA, USA), and the percentage of hemolysis was calculated using the formula:

3.6. Antimicrobial Activity of the Synthesized Amidrazones 2a–2g

3.6.1. Disk Diffusion Method

To preliminarily determine the sensitivity of the tested strains to the derivatives, the compounds’ activity was tested using the disk diffusion method according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing [

65].

The turbidity of the cultures was set to 0.5 McFarland units, and 100 μL of the culture was applied to plates containing MH agar medium. Then, 10 μL of the tested compounds dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 10 mg/mL (yielding 100 μg/disk) were applied onto sterile 6 mm diameter filter paper disks (BioMaxima, Lublin, Poland) and dried at room temperature. The disks with the tested compounds were then placed on the seeded plates. As controls, DMSO (10 μL) and filter paper disks containing defined concentrations of the antibiotics ampicillin (10 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), or fluconazole (25 μg) (BioMaxima, Lublin, Poland) were used. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h.

Compounds that inhibited microbial growth by at least 8 mm were selected for MIC determination by the microdilution method.

3.6.2. Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

The antimicrobial activity of

2a–

2g was determined by the broth microdilution method, according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [

66]. Each compound was dissolved in DMSO to a concentration of 10.24 mg/mL, then diluted in Mueller-Hinton broth (MH), and serial two-fold dilutions were performed (ranging from 512 to 0.5 μg/mL) in a 96-well microplate.

In order to determine the antibacterial properties of 2a–2g, the following strains of bacteria were chosen: Gram-positive (pathogenic S. aureus ATCC 25923, M. luteus ATCC 4698, E. faecalis ATCC 29212, and non-pathogenic M. smegmatis, Gordonia rubripertincta) and Gram-negative (drug-sensitive E. coli ATCC 25922, Y. enterocolitica serotype O3, and drug-resistant K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853). Antifungal properties of 2a–2g were tested on the pathogenic yeast C. albicans ATCC 90028.

The MIC value was defined as the lowest concentration of the compound at which no bacterial growth was observed. The optical density was measured spectrophotometrically at 550 nm; the control was a bacterial culture without the addition of the amidrazones.

3.6.3. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Analysis

Amidrazone 2d, which exhibited the best antimicrobial potency, was selected for analysis of activity against S. aureus ATCC 25923, M. smegmatis, and C. albicans ATCC 90028 using atomic force microscopy (AFM). Briefly, 2d was dissolved in DMSO to a concentration of 6.4 mg/mL and added to MH broth to obtain the ½ MIC value specific for each strain. Then, the tested microorganisms’ culture, corresponding to 0.5 on the McFarland scale, was added. The control was a culture prepared in the same way, but without the addition of 2d. The cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h and centrifuged for 5 min at 14,500 rpm. The bacterial pellet was washed first with sterile saline, then twice with deionized water. After the final centrifugation step, the bacteria were suspended in 5 μL of sterile water and applied to the surface of mica disks, left to dry overnight at room temperature. The surface of the cells was measured using NanoScope V AFM in the Peak-Force Quantitative Nanomechanical Mapping Mode (Bruker, Veeco Instruments Inc., Billerica, MA, USA) and NanoScope 8.15 software.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

All the experiments for the biological properties of the synthesized amidrazones were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as mean (c) ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The principal component analysis (PCA) was utilized as a data reduction technique to generate a visual plot of the synthesized amidrazone derivatives and their distribution on a score plot and to visualize potential relationships among their biological properties. However, the hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was performed using the Ward clustering algorithm with squared Euclidean distance to sort the investigated amidrazones into groups. Moreover, to analyze the relationships among the biological features of amidrazones, Pearson correlations were calculated and depicted as a correlation color matrix.

The statistical analysis was carried out using Statistica 8.0 software (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

4. Conclusions

Seven N3-substituted amidrazones 2a–2g containing aryl groups such as phenyl, 4-methylphenyl, 4-nitrophenyl, 2-pyridyl, and/or 4-pyridyl, were synthesized and their molecular structures confirmed using 1H, 13C, and 15N NMR spectroscopy. The evaluation of biological properties revealed that all synthesized compounds exhibited antioxidant activity, inhibitory activity against α-amylase, lipase, and pepsin, cytotoxic activity, as well as antibacterial and antifungal activity. Interestingly, two amidrazones, 2a, with two phenyl groups in Ar1 and Ar2 positions, and 2d, substituted by 2-pyridyl and 4-nitrophenyl in these positions, had the highest ability to react with the DPPH radical and were capable of reducing the Fe3+-TPTZ complex. In addition, 2d amidrazone had potential inhibitory activity against α-amylase at the highest concentration (1 mg/mL) and lipase and pepsin at the lowest concentration (0.2 mg/mL). Then, 2b and 2d (with 2-pyridyl as Ar1 and phenyl or 4-nitrophenyl as Ar2) at the highest concentration had vigorous cytotoxic activity, whereas the cytotoxic effect of all 2a–2g compounds at lower concentrations was negligible. Moreover, 2d exhibited the most potent antibacterial activity against all Gram-positive bacterial strains and the antifungal activity, whereas it was much less effective against Gram-negative bacterial strains. The varying sensitivity of the tested microorganisms to 2d reflects noticeable differences in cell surface properties. The most probable reason for the increase in surface roughness is the rupture of bacterial and fungal cells due to the amidrazone binding.

The chemometric analysis conducted for this study confirmed significant differences in the biological activity of 2a–2g, depending on the Ar1 and Ar2 substituents. At the same time, PCA and HCA displayed some common biological properties among these amidrazones, allowing for them to be grouped into characteristic clusters. This may indicate a future biological use of amidrazones, and not just as building blocks for synthesis, as they have been used so far.