Effects of Fentanyl-Adulterated Methamphetamine on Circulating Ghrelin in Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

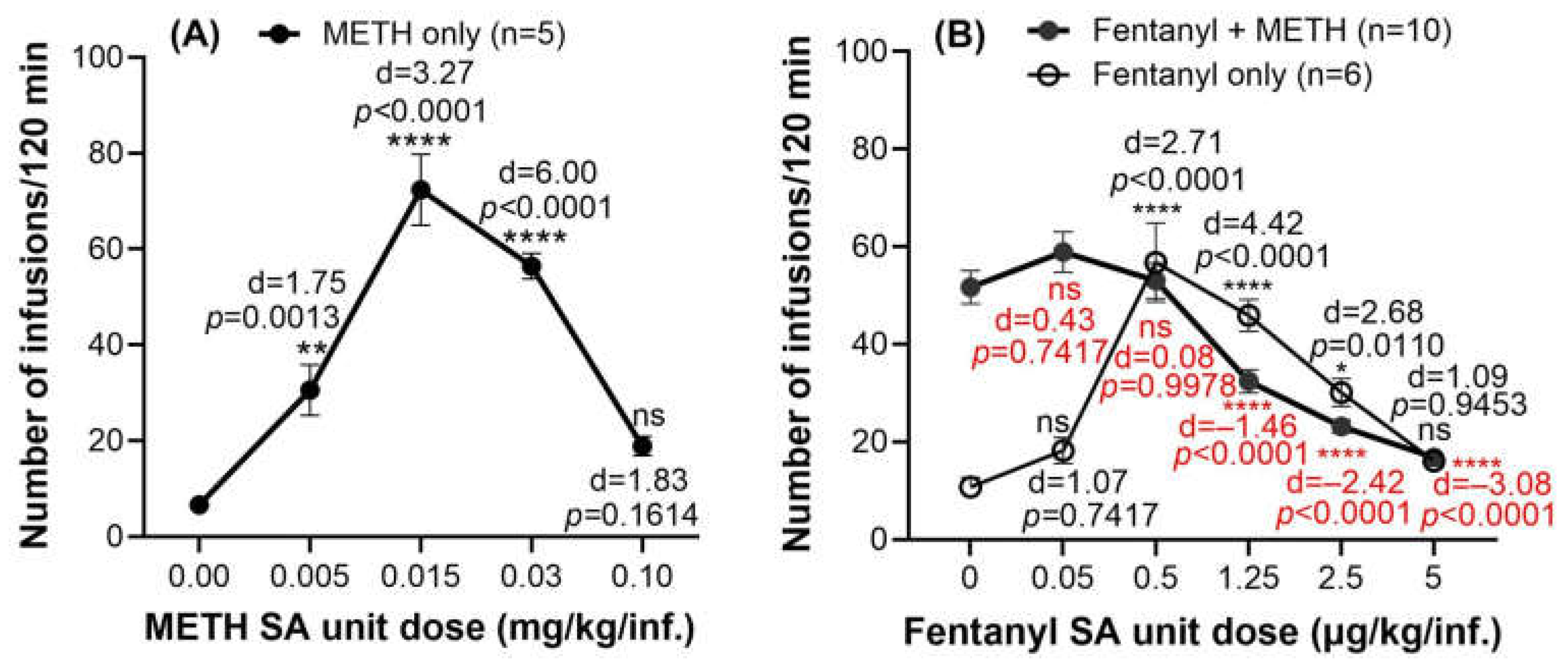

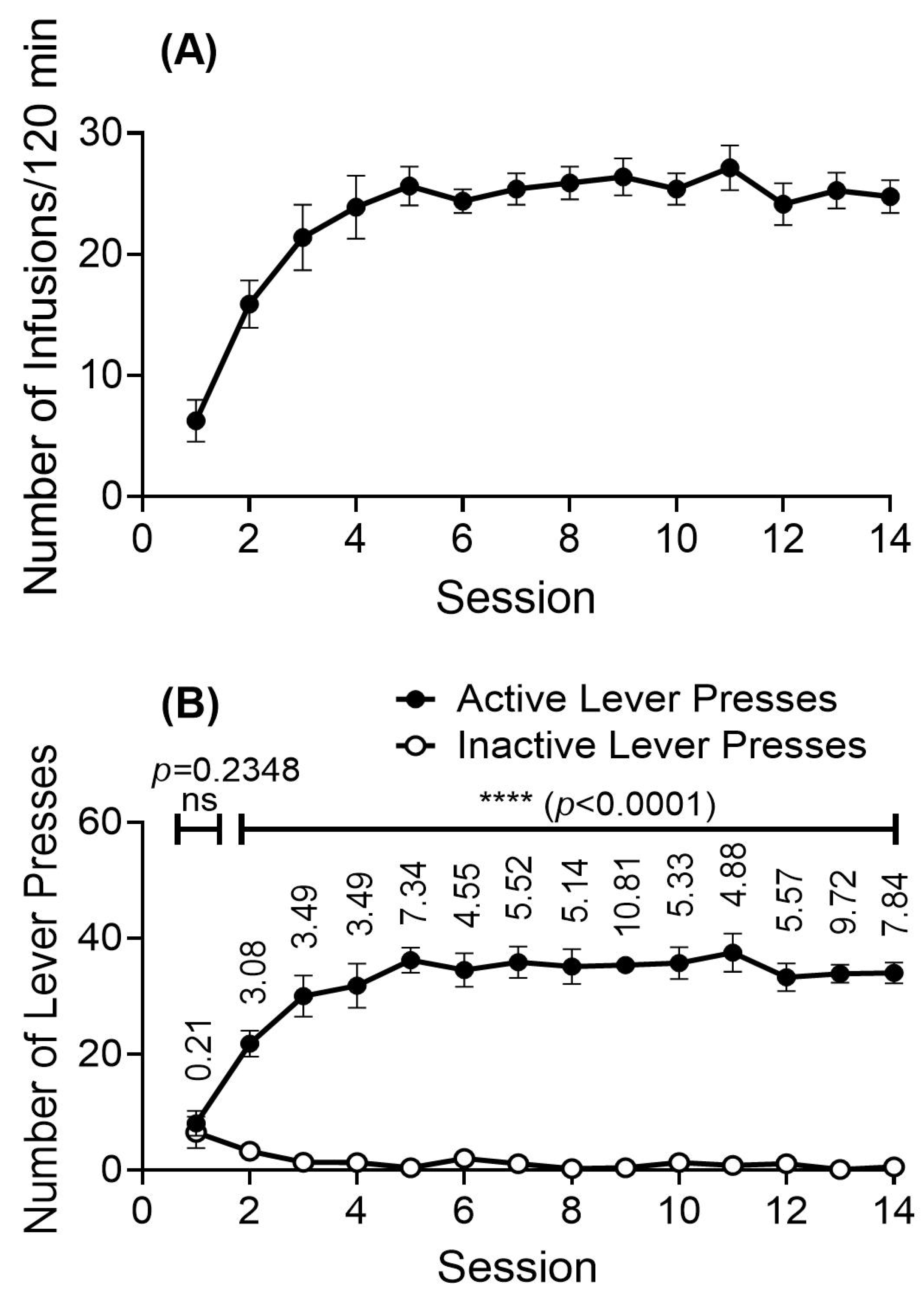

2.1. Drug-Taking Behavior When Rats Intravenously Self-Administer the METH-Fentanyl Polydrug

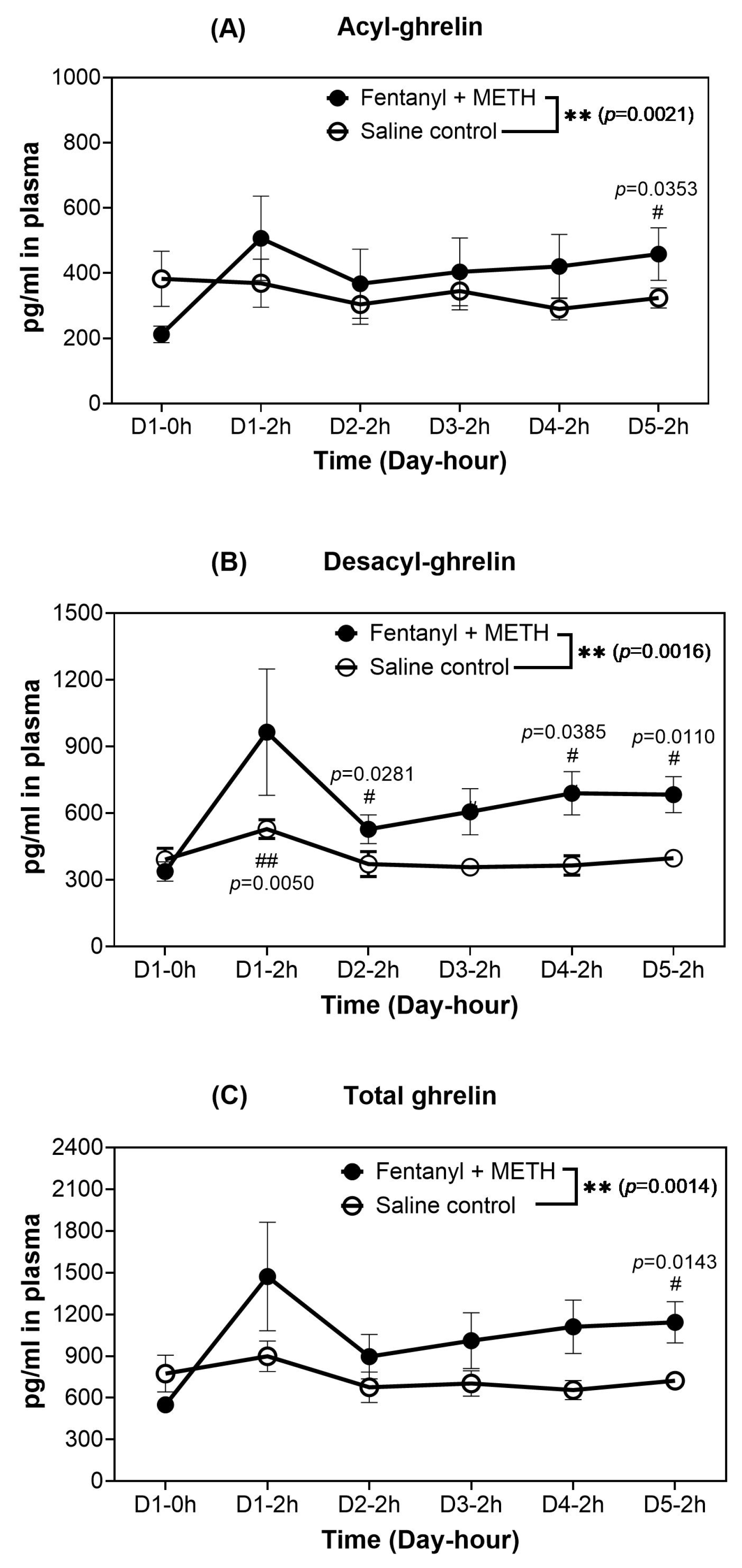

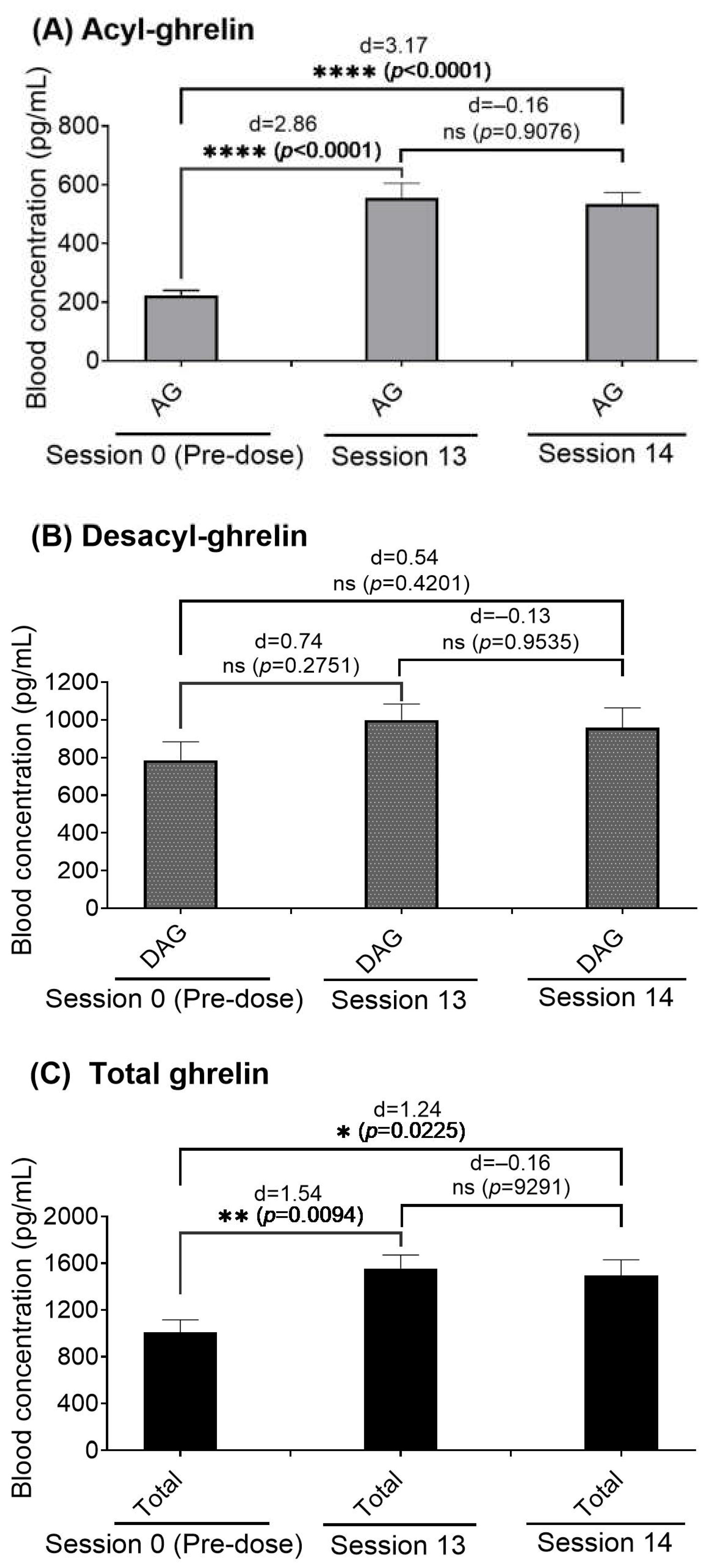

2.2. Effects of the METH-Fentanyl Polydrug on Blood Plasma Concentrations of Ghrelin in Rats

| Analyte | Day at 2 h | Mean of the Changes (pg/mL) from Day 0-0 h | Range of the Changes (pg/mL) a | 95%CI of the Changes (pg/mL) | p (t-Test) | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AG | Day 1 | 295 | 8 to 563 | 68 to 521 | 0.0256 | 1.29 |

| Day 2 | 156 | 34 to 540 | −11 to 323 | 0.0637 | 0.82 | |

| Day 3 | 192 | 58 to 597 | 29 to 355 | 0.0343 | 1.04 | |

| Day 4 | 209 | 53 to 575 | 55 to 362 | 0.0223 | 1.19 | |

| Day 5 | 247 | 80 to 422 | 125 to 369 | 0.0053 | 1.68 | |

| DAG | Day 1 | 627 | 182 to 2066 | 40 to 1214 | 0.0453 | 1.26 |

| Day 2 | 190 | 81 to 401 | 101 to 278 | 0.0042 | 1.40 | |

| Day 3 | 269 | 115 to 644 | 111 to 428 | 0.0104 | 1.38 | |

| Day 4 | 352 | 156 to 733 | 174 to 530 | 0.0058 | 1.90 | |

| Day 5 | 346 | 161 to 407 | 218 to 474 | 0.0016 | 2.17 | |

| Total ghrelin | Day 1 | 922 | 248 to 2740 | 140 to 1704 | 0.0345 | 1.35 |

| Day 2 | 346 | 118 to 941 | 98 to 593 | 0.0205 | 1.17 | |

| Day 3 | 461 | 203 to 1241 | 148 to 775 | 0.0172 | 1.27 | |

| Day 4 | 561 | 209 to 1308 | 232 to 889 | 0.0102 | 1.61 | |

| Day 5 | 593 | 241 to 978 | 359 to 827 | 0.0021 | 2.15 |

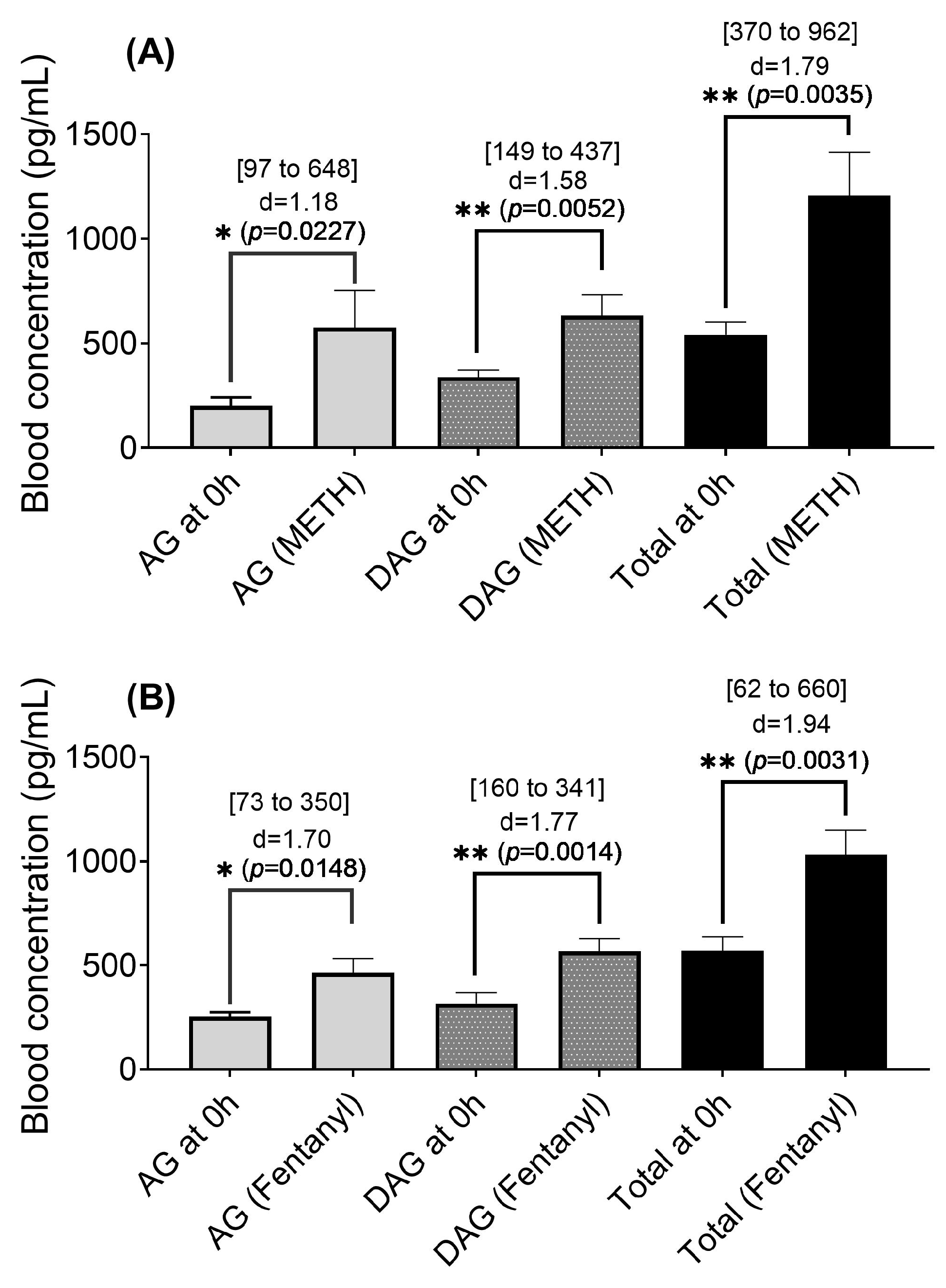

2.3. Blood Ghrelin Levels in Rats That Self-Administrated the METH-Fentanyl Polydrug

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Drugs

4.2. Apparatus

4.3. Intranvenous Catheterization Surgery

4.4. Self-Administration Training and Dose–Response Curve

4.5. Effects of Manually Administered METH-Fentanyl Polydrug on Ghrelin Levels

4.6. Ghrelin Concentrations in Rats That Intravenously Self-Administered the METH-Fentanyl Polydrug

4.7. Sample Analysis

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fentanyl. Available online: https://www.dea.gov/factsheets/fentanyl (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Facts About Fentanyl. Available online: https://www.dea.gov/resources/facts-about-fentanyl (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Klobucista, C.; Ferragamo, M. Fentanyl and the U.S. Opioid Epidemic, Council on Foreign Relations. 2023. Available online: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/fentanyl-and-us-opioid-epidemic (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Nodell, B. Co-Addiction of Meth and Opioids Hinders Treatment: Study Finds Meth Undermines Success in Treatment for Opioid-Use Disorder. 2019. Available online: https://newsroom.uw.edu/news/co-addiction-meth-and-opioids-hinders-treatment (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Wei, H.; Maul, E.C.; Kyomuhangi, A.; Park, S.; Mutchler, M.L.; Zhan, C.-G.; Zheng, F. Effects of Fentanyl-Laced Cocaine on Circulating Ghrelin, Insulin, and Glucose Levels in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland, N.; Sanger-Katz, M. Overdose Deaths Continue Rising, with Fentanyl and Meth Key Culprits. International New York Times, 11 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- HealthDay. U.S. Deaths Involving Meth Are Skyrocketing, Fentanyl a Big Factor. 2023. Available online: https://www.healthday.com/methamphetamine-2659441796.html (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Daniulaityte, R.; Ruhter, L.; Juhascik, M.; Silverstein, S. Attitudes and experiences with fentanyl contamination of methamphetamine: Exploring self-reports and urine toxicology among persons who use methamphetamine and other drugs. Harm Reduct. J. 2023, 20, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twillman, R.K.; Dawson, E.; LaRue, L.; Guevara, M.G.; Whitley, P.; Huskey, A. Evaluation of Trends of Near-Real-Time Urine Drug Test Results for Methamphetamine, Cocaine, Heroin, and Fentanyl. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e1918514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, K.D.; Fiuty, P.; Page, K.; Tracy, E.C.; Nocera, M.; Miller, C.W.; Tarhuni, L.J.; Dasgupta, N. Prevalence of fentanyl in methamphetamine and cocaine samples collected by community-based drug checking services. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2023, 252, 110985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, M.S.; Kasper, Z.A.; Cicero, T.J. Twin epidemics: The surging rise of methamphetamine use in chronic opioid users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 193, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranaldi, R.; Wise, R.A. Intravenous self-administration of methamphetamine-heroin (speedball) combinations under a progressive-ratio schedule of reinforcement in rats. NeuroReport 2000, 11, 2621–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maucione, S. Fentanyl Mixed with Cocaine or Meth Is Driving the ‘4th Wave‘ of the Overdose Crisis. Health Reporting in the States, 14 September 2023. Available online: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/2009/2014/1199396794/fentanyl-mixed-with-cocaine-or-meth-is-driving-the-1199396794th-wave-of-the-overdose-cris (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Sustkova-Fiserova, M.; Charalambous, C.; Khryakova, A.; Certilina, A.; Lapka, M.; Šlamberová, R. The role of ghrelin/GHS-R1A signaling in nonalcohol drug addictions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 761. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Zheng, F.; Zhan, C.-G. Modeling Differential Binding of α4β2 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor with Agonists and Antagonists. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 16691–16696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, M.; Hosoda, H.; Date, Y.; Nakazato, M.; Matsuo, H.; Kangawa, K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature 1999, 402, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zallar, L.J.; Farokhnia, M.; Tunstall, B.J.; Vendruscolo, L.F.; Leggio, L. Chapter Four—The Role of the Ghrelin System in Drug Addiction. In The Role of Neuropeptides in Addiction and Disorders of Excessive Consumption; International Review of Neurobiology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Volume 136, pp. 89–119. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, G.; Rea, W.; Quiroz, C.; Moreno, E.; Gomez, D.; Wenthur, C.J.; Casadó, V.; Leggio, L.; Hearing, M.C.; Ferré, S. Complexes of ghrelin GHS-R1a, GHS-R1b, and dopamine D1 receptors localized in the ventral tegmental area as main mediators of the dopaminergic effects of ghrelin. J. Neurosci. 2022, 42, 940–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerlhag, E.; Egecioglu, E.; Dickson, S.L.; Engel, J.A. Ghrelin receptor antagonism attenuates cocaine- and amphetamine-induced locomotor stimulation, accumbal dopamine release, and conditioned place preference. Psychopharmacology 2010, 211, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, C.; Cornish, J.L.; Baracz, S.J.; Suraev, A.; McGregor, I.S. Adolescent pre-treatment with oxytocin protects against adult methamphetamine-seeking behavior in female rats. Addict. Biol. 2016, 21, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Du, X.; Chen, M.; Zhu, S. Growth Hormone Secretagogue Receptor 1A Antagonist JMV2959 Effectively Prevents Morphine Memory Reconsolidation and Relapse. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 718615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustkova-Fiserova, M.; Puskina, N.; Havlickova, T.; Lapka, M.; Syslova, K.; Pohorala, V.; Charalambous, C. Ghrelin receptor antagonism of fentanyl-induced conditioned place preference, intravenous self-administration, and dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens in rats. Addict. Biol. 2020, 25, e12845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsson, C.E.; Vestlund, J.; Jerlhag, E. A ghrelin receptor antagonist reduces the ability of ghrelin, alcohol or amphetamine to induce a dopamine release in the ventral tegmental area and in nucleus accumbens shell in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 899, 174039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowley, W.R.; Ramoz, G.; Keefe, K.A.; Torto, R.; Kalra, S.P.; Hanson, G.R. Differential effects of methamphetamine on expression of neuropeptide Y mRNA in hypothalamus and on serum leptin and ghrelin concentrations in ad libitum-fed and schedule-fed rats. Neuroscience 2005, 132, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessari, M.; Catalano, A.; Pellitteri, M.; Di Francesco, C.; Marini, F.; Gerrard, P.A.; Heidbreder, C.A.; Melotto, S. Correlation between serum ghrelin levels and cocaine-seeking behaviour triggered by cocaine-associated conditioned stimuli in rats. Addict. Biol. 2007, 12, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Z.B.; Wang, B.; Gardner, E.L.; Wise, R.A. Cocaine and cocaine expectancy increase growth hormone, ghrelin, GLP-1, IGF-1, adiponectin, and corticosterone while decreasing leptin, insulin, GIP, and prolactin. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2019, 176, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.-B.; Galaj, E.; Alén, F.; Wang, B.; Bi, G.-H.; Moore, A.R.; Buck, T.; Crissman, M.; Pari, S.; Xi, Z.-X.; et al. Involvement of the ghrelin system in the maintenance and reinstatement of cocaine-motivated behaviors: A role of adrenergic action at peripheral β1 receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 1449–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, S.E.; Hendrick, E.S.; Beardsley, P.M. Glial cell modulators attenuate methamphetamine self-administration in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 701, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Pena-Bravo, J.I.; Leong, K.-C.; Lavin, A.; Reichel, C.M. Methamphetamine self-administration modulates glutamate neurophysiology. Brain Struct. Funct. 2017, 222, 2031–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, S.R.; Gulley, J.M. Effects of the GluN2B antagonist, Ro 25-6981, on extinction consolidation following adolescent- or adult-onset methamphetamine self-administration in male and female rats. Behav. Pharmacol. 2020, 31, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luikinga, S.J.; Madsen, H.B.; Zbukvic, I.C.; Perry, C.J.; Lawrence, A.J.; Kim, J.H. Adolescent vulnerability to methamphetamine: Dose-related escalation of self-administration and cue extinction deficits. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2025, 269, 112599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, A.; Comanescu, M.A.; Green, O.; Kubic, T.A.; Lombardi, J.R. Detection and Quantitation of Trace Fentanyl in Heroin by Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 12678–12685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauss, S.T.; Ross, D.; Forbes, T.P. Separation and Detection of Trace Fentanyl from Complex Mixtures Using Gradient Elution Moving Boundary Electrophoresis. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 13014–13021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, E.A.; Schwienteck, K.L.; Robinson, H.L.; Lawson, S.T.; Banks, M.L. A drug-vs-food “choice” self-administration procedure in rats to investigate pharmacological and environmental mechanisms of substance use disorders. J. Neurosci. Methods 2021, 354, 109110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, M.; Langlet, F.; Lafont, C.; Molino, F.; Hodson, D.J.; Roux, T.; Lamarque, L.; Verdié, P.; Bourrier, E.; Dehouck, B.; et al. Rapid sensing of circulating ghrelin by hypothalamic appetite-modifying neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 1512–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, W.A.; Tschöp, M.; Robinson, S.M.; Heiman, M.L. Extent and Direction of Ghrelin Transport Across the Blood-Brain Barrier Is Determined by Its Unique Primary Structure. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 302, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerlhag, E.; Egecioglu, E.; Landgren, S.; Salome, N.; Heilig, M.; Moechars, D.; Datta, R.; Perrissoud, D.; Dickson, S.L.; Engel, J.A. Requirement of central ghrelin signaling for alcohol reward. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 11318–11323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerlhag, E.; Engel, J.A. Ghrelin receptor antagonism attenuates nicotine-induced locomotor stimulation, accumbal dopamine release and conditioned place preference in mice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011, 117, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.A.; Nylander, I.; Jerlhag, E. A ghrelin receptor (GHS-R1A) antagonist attenuates the rewarding properties of morphine and increases opioid peptide levels in reward areas in mice. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 25, 2364–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerabek, P.; Havlickova, T.; Puskina, N.; Charalambous, C.; Lapka, M.; Kacer, P.; Sustkova-Fiserova, M. Ghrelin receptor antagonism of morphine-induced conditioned place preference and behavioral and accumbens dopaminergic sensitization in rats. Neurochem. Int. 2017, 110, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlickova, T.; Charalambous, C.; Lapka, M.; Puskina, N.; Jerabek, P.; Sustkova-Fiserova, M. Ghrelin Receptor Antagonism of Methamphetamine-Induced Conditioned Place Preference and Intravenous Self-Administration in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, V.N.; Ralevski, E. The role of ghrelin in addiction: A review. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 2725–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchouk, O.; Tufvesson-Alm, M.; Jerlhag, E. An Overview of Appetite-Regulatory Peptides in Addiction Processes; From Bench to Bed Side. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 774050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhea, E.M.; Salameh, T.S.; Gray, S.; Niu, J.; Banks, W.A.; Tong, J. Ghrelin transport across the blood–brain barrier can occur independently of the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Mol. Metab. 2018, 18, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsuka, H.; Fujita, K.; Kobayashi, H. Pharmacokinetics of fentanyl in male and female rats after intravenous administration. Arzneimittelforschung 2007, 57, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, H.E.; Huhn, A.S.; Dunn, K.E. Fentanyl Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion: Narrative Review and Clinical Significance Related to Illicitly Manufactured Fentanyl. J. Addict. Med. 2023, 17, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.J.; Wei, H.; Chandar, N.B.; Zheng, F.; Zhan, C.-G. Development of a Ghrelin Deacylase to Attenuate Drug Reward and Associated Effects of Methamphetamine. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2025, 8, 3259–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, F.; Jin, Z.; Deng, J.; Chen, X.; Zheng, X.; Wang, G.; Kim, K.; Shang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhan, C.-G. Development of a Highly Efficient Long-Acting Cocaine Hydrolase Entity to Accelerate Cocaine Metabolism. Bioconjug. Chem. 2022, 33, 1340–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhan, C.-G.; Zheng, F. Cebranopadol reduces cocaine self-administration in male rats: Dose, treatment and safety consideration. Neuropharmacology 2020, 172, 108128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Fentanyl (µg/kg/Infusion) | 0.0 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 1.25 | 2.5 | 5.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of infusions | 52 | 59 | 53 | 32 | 23 | 17 |

| Consumed METH (mg/kg) | 1.551 | 1.767 | 1.590 | 0.972 | 0.695 | 0.506 |

| Consumed fentanyl (mg/kg) | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.027 | 0.041 | 0.058 | 0.084 |

| Ratio of fentanyl to METH (%) | 0.000 | 0.167 | 1.667 | 4.167 | 8.333 | 16.667 |

| Ratio of fentanyl to total amount of drugs (%) | 0.000 | 0.166 | 1.639 | 4.000 | 7.692 | 14.286 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, H.; Maul, E.C.; Park, S.; Fatema, K.; Peter, D.J.; Zhan, C.-G.; Zheng, F. Effects of Fentanyl-Adulterated Methamphetamine on Circulating Ghrelin in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411806

Wei H, Maul EC, Park S, Fatema K, Peter DJ, Zhan C-G, Zheng F. Effects of Fentanyl-Adulterated Methamphetamine on Circulating Ghrelin in Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411806

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Huimei, Elise C. Maul, Shawn Park, Kaniz Fatema, Daniel J. Peter, Chang-Guo Zhan, and Fang Zheng. 2025. "Effects of Fentanyl-Adulterated Methamphetamine on Circulating Ghrelin in Rats" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411806

APA StyleWei, H., Maul, E. C., Park, S., Fatema, K., Peter, D. J., Zhan, C.-G., & Zheng, F. (2025). Effects of Fentanyl-Adulterated Methamphetamine on Circulating Ghrelin in Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411806