Fatal Myocarditis Following Adjuvant Immunotherapy: A Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

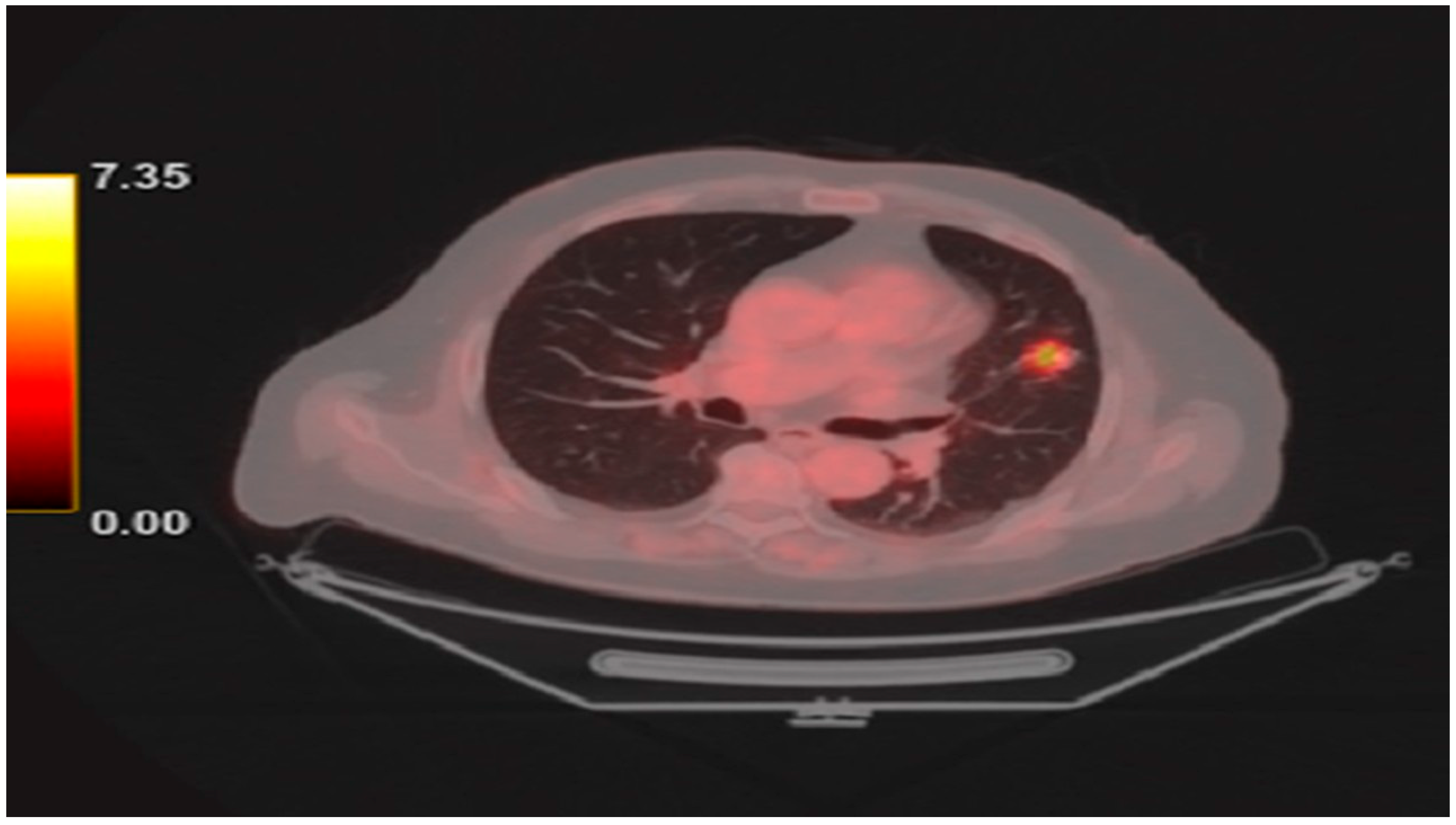

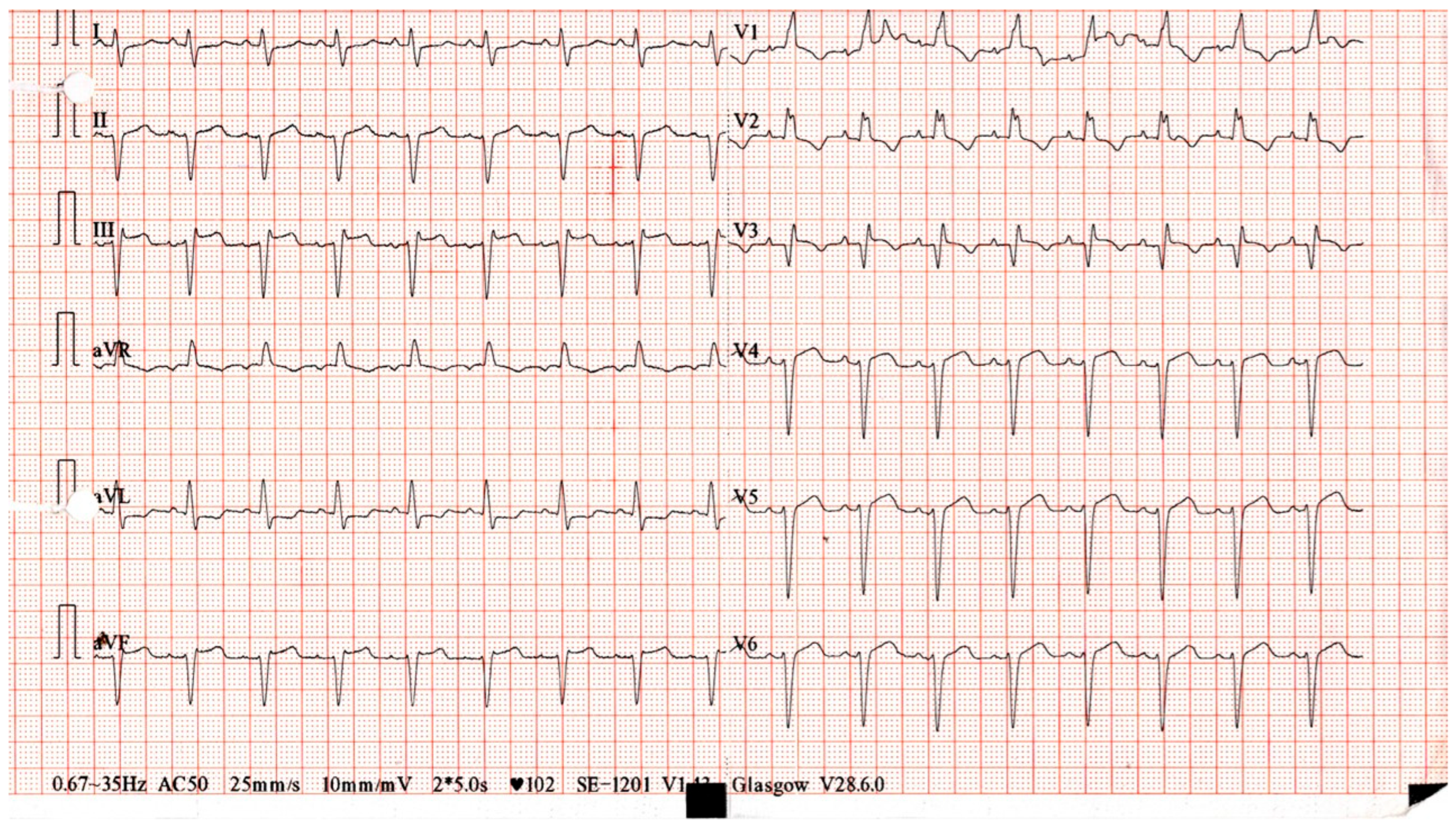

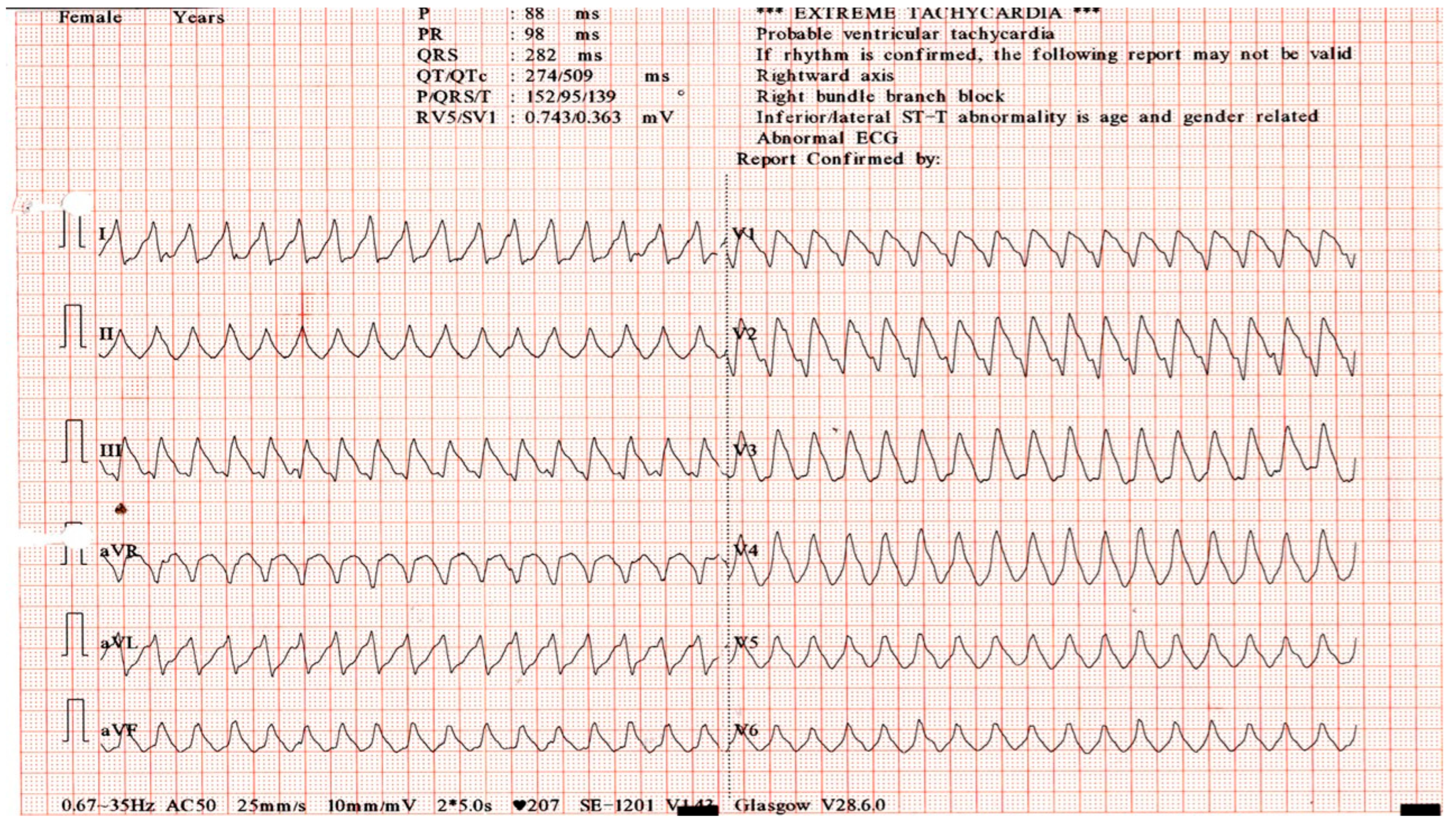

2. Detailed Case Description

3. Review of the Literature

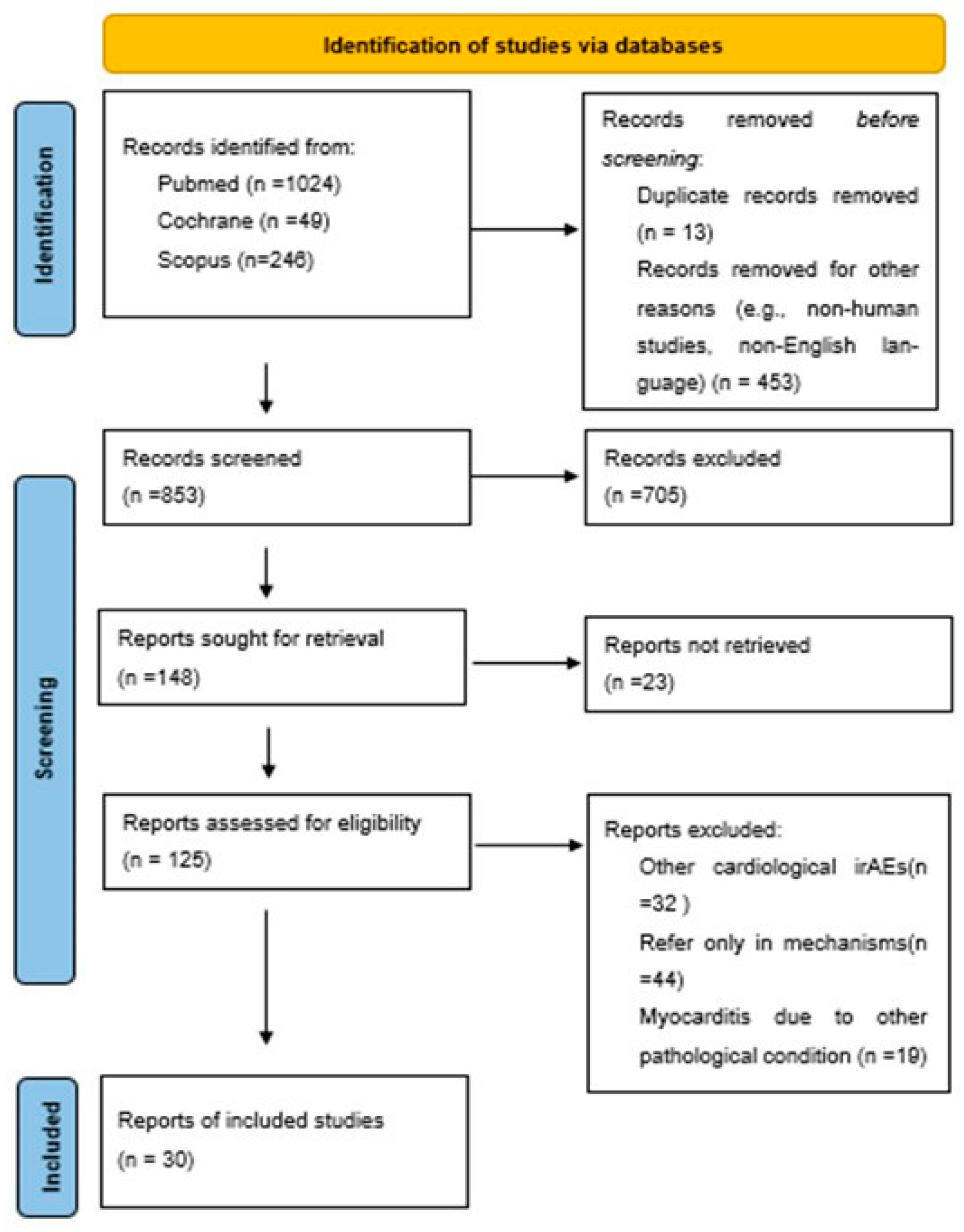

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Search Strategy

3.1.2. Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.1.3. Article Selection and Data Extraction

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zavaleta-Monestel, E.; García-Montero, J.; Anchía-Alfaro, A.; Rojas-Chinchilla, C.; Quesada-Villaseñor, R.; Arguedas-Chacón, S.; Barrantes-López, M.; Molina-Sojo, P.; Zovi, A.; Zúñiga-Orlich, C.; et al. Myocarditis Induced by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: An Exploratory Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e67314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, R.W.; Barbie, D.A.; Flaherty, K.T. Mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 118, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C. A decade of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhu, G.; Tamada, K.; Chen, L. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin-10 secretion. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 1365–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, V.A.; Grabie, N.; Duramad, P.; Stavrakis, G.; Sharpe, A.; Lichtman, A. CTLA-4 Ablation and Interleukin-12–Driven Differentiation Synergistically Augment Cardiac Pathogenicity of Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes. Circ. Res. 2007, 101, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben, A.; Petaccia de Macedo, M.; McQuade, J.; Joon, A.; Ren, Z.; Calderone, T.; Conner, B.; Wani, K.; Cooper, Z.A.; Hussein Tawbi, H.; et al. Comparative immunologic characterization of autoimmune giant cell myocarditis with ipilimumab. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1361097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganatra, S.; Neilan, T.G. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Associated Myocarditis. Oncologist 2018, 23, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.B.; Balko, J.M.; Compton, M.L.; Chalkias, S.; Gorham, J.; Xu, Y.; Hicks, M.; Puzanov, I.; Alexander, M.R.; Bloomer, L.T.; et al. Fulminant Myocarditis with Combination Immune Checkpoint Blockade. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1749–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haanen, J.; Obeid, M.; Spain, L.; Carbonnel, F.; Wang, Y.; Robert, C.; Lyon, A.R.; Wick, W.; Kostine, M.; Peters, S.; et al. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 1217–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, A.R.; López-Fernández, T.; Couch, L.S.; Asteggiano, R.; Aznar, M.C.; Bergler-Klein, J.; Boriani, G.; Cardinale, D.; Cordoba, R.; Cosyns, B.; et al. 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardio-oncology developed in collaboration with the European Hematology Association (EHA), the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ESTRO) and the International Cardio-Oncology Society (IC-OS) Developed by the task force on cardio-oncology of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J.-Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 23, e333–e465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schneider, B.J.; Naidoo, J.; Santomasso, B.D.; Lacchetti, C.; Adkins, S.; Anadkat, M.; Atkins, M.B.; Brassil, K.J.; Caterino, J.M.; Chau, I.; et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 4073–4126, Erratum in J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arangalage, D.; Delyon, J.; Lermuzeaux, M.; Ekpe, K.; Ederhy, S.; Pages, C.; Céleste Lebbé, C. Survival After Fulminant Myocarditis Induced by Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 167, 683–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Jia, Y.; Liu, Q.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, H.; Dong, X.; Huang, J.; Lu, J.; Yin, Q. Myocarditis related to immune checkpoint inhibitors treatment: Two case reports and literature review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 8512–8517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M.; Mustafa, S.; Elkherpitawy, I.; Meleka, M. A Fatal Case of Pembrolizumab-Induced Myocarditis in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. JACC Case Rep. 2020, 2, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnone, M.; Dall’Ara, G.; Bergamaschi, L.; Gardini, E.; Pizzi, C.; Galvani, M. Left Ventricular Thrombosis in Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Myocarditis Mimicking ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. JACC Case Rep. 2024, 29, 102663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigeri, M.; Meyer, P.; Banfi, C.; Giraud, R.; Hachulla, A.L.; Spoerl, D.; Friedlaender, A.; Pugliesi-Rinaldi, A.; Dietrich, P.Y. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Associated Myocarditis: A New Challenge for Cardiologists. Can. J. Cardiol. 2018, 34, 92.e1–92.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumitsu, M.; Ariyasu, R.; Ishiyama, M.; Mochizuki, T.; Takeda, K.; Ono, M.; Oyakawa, T.; Ebihara, A.; Nishizawa, A.; Tomomatsu, J.; et al. Myocarditis associated with immune-checkpoint inhibitors diagnosed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Int. Cancer Conf. J. 2022, 12, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari-Gilani, K.; Tirumani, S.H.; Smith, D.A.; Nelson, A.; Alahmadi, A.; Hoimes, C.J.; Ramaiya, N.H. Myocarditis associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: A case report of three patients. Emerg. Radiol. 2020, 27, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, C.; Jin, S.; Yi, Z.; Wang, C.; Pan, X.; Huang, H. A case of subclinical immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myocarditis in non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Pulm. Med. 2023, 23, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Huertas, R.; Saavedra Serrano, C.; Perna, C.; Ferrer Gómez, A.; Alonso Gordoa, T. Cardiac toxicity of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: A clinical case of nivolumab-induced myocarditis and review of the evidence and new challenges. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 4541–4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnik, M.; Kolar Kus, P.; Krepek, M.; Vlaović, J.; Podbregar, M. Fatal rhabdomyolysis and fulminant myocarditis with malignant arrhythmias after one dose of ipilimumab and nivolumab. Immunotherapy 2024, 16, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bras, P.; Plard, L.; Le Gouill, C.; Piriou, N.; Touchefeu, Y. Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis Mimicking Immune Checkpoint-Induced Myocarditis in a Patient Treated with Atezolizumab and Bevacizumab for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Case Report. Case Rep. Oncol. 2022, 15, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izumi, R.; Hashimoto, T.; Kisanuki, H.; Ikuta, K.; Otsuru, W.; Asakawa, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Misumi, K.; Fujino, T.; Shinohara, K.; et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related fulminant myocarditis. Cardio-Oncology 2024, 10, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R.I.; Seuthe, K.; Lennartz, S.; Weber, J.P.; Kreuzberg, N.; Klingel, K.; Bröckelmann, P.J. Case Report: Sudden very late-onset near fatal PD1 inhibitor-associated myocarditis with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest after >2.5 years of pembrolizumab treatment. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1328378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Yang, J.; Lin, Y.; Li, T.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, J.; Dong, C. Immune Myocarditis Overlapping With Myasthenia Gravis Due to Anti-PD-1 Treatment for a Chordoma Patient: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 682262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zeng, Z.; Cao, J.; Li, X.; Muhetaer, M.; Jin, Z.; Cai, H.; Lu, Z. Sintilimab-Induced Myocarditis in a Patient with Gastric Cancer: A Case Report and Literature Review. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2023, 10, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Fan, Y.; Guo, J.; Bian, N.; Chen, D. Fulminant myocarditis caused by immune checkpoint inhibitor: A case report and possible treatment inspiration. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 2020–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariniello, M.; Arrivi, G.; Tufano, L.; Lauletta, A.; Moro, M.; Tini, G.; Garibaldi, M.; Giusti, R.; Mazzuca, F. Management of overlapping immune-related myocarditis, myositis, and myasthenia in a young patient with advanced NSCLC: A case report. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1431971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, D.R.; Accola, M.A.; Rehrauer, W.M.; Corliss, R.F. Fatal Myocarditis Following Treatment with the PD-1 Inhibitor Nivolumab. J. Forensic Sci. 2018, 63, 954–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyauchi, Y.; Naito, H.; Tsunemori, H.; Tani, R.; Hasui, Y.; Miyake, Y.; Minamino, T.; Ishikawa, R.; Kushida, Y.; Haba, R.; et al. Myocarditis as an immune-related adverse event following treatment with ipilimumab and nivolumab combination therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2021, 15, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge, C.; Maeng, H.; Brofferio, A.; Apolo, A.B.; Sathya, B.; Arai, A.E.; Gulley, J.L.; Bilusic, M. Myocarditis in a patient treated with Nivolumab and PROSTVAC: A case report. J. Immunother. Cancer 2018, 6, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, C.; Cong, X.; Sun, L.; Sun, X.; Chen, C.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L. Efficacy of high-dose steroids versus low-dose steroids in the treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated myocarditis: A case series and systematic review. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1455347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naganuma, K.; Horita, Y.; Matsuo, K.; Miyama, Y.; Mihara, Y.; Yasuda, M.; Nakano, S.; Hamaguchi, T. An Autopsy Case of Late-onset Fulminant Myocarditis Induced by Nivolumab in Gastric Cancer. Intern. Med. 2022, 61, 2867–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, D.P.J.R.; Zachariah, S.; Scollan, D.; Shaikh, A. Myocarditis: A Rare Complication of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Cureus 2024, 16, e60459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Chen, L.; Qian, K.; Xu, X. Severe immune-related hepatitis and myocarditis caused by PD-1 inhibitors in the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer: A case report. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, H.; Nanjo, S.; Sato, S.; Kotani, H.; Nishiyama, A.; Yamashita, K.; Ohtsubo, K.; Suzuki, C.; Shimojima, M.; Yano, S.; et al. Effectiveness of Additional Immunosuppressive Drugs for Corticosteroid-refractory Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-induced Myocarditis: Two Case Reports. Intern. Med. 2025, 64, 1205–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Qi, C.; Zeng, H.; Wei, Q.; Huang, Q.; Pu, X.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Tian, P. Steroid-Refractory Myocarditis Induced by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Responded to Infliximab: Report of Two Cases and Literature Review. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2024, 24, 1174–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itzhaki Ben Zadok, O.; Ben-Avraham, B.; Nohria, A.; Orvin, K.; Nassar, M.; Iakobishvili, Z.; Neiman, V.; Goldvaser, H.; Kornowski, R.; Gal, T.B. Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Fulminant Myocarditis and Cardiogenic Shock. JACC CardioOncology 2019, 1, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Jones-O’Connor, M.; Awadalla, M.; Zlotoff, D.A.; Thavendiranathan, P.; Groarke, J.D.; Villani, A.C.; Lyon, A.R.; Neilan, T.G. Cardiotoxicity of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 21, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, J.E.; Allenbach, Y.; Vozy, A.; Brechot, N.; Johnson, D.B.; Moslehi, J.J.; Kerneis, M. Abatacept for Severe Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor–Associated Myocarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 2377–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.; Khunger, A.; Vachhani, P.; Colvin, T.A.; Hattoum, A.; Spangenthal, E.; Curtis, A.B.; Dy, G.K.; Ernstoff, M.S.; Puzanov, I. Cardiac Toxicity Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Case Series and Review of the Literature. Case Rep. Oncol. 2019, 12, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keir, M.E.; Liang, S.C.; Guleria, I.; Latchman, Y.E.; Qipo, A.; Albacker, L.A.; Koulmanda, M.; Freeman, G.J.; Sayegh, M.H.; Sharpe, A.H. Tissue expression of PD-L1 mediates peripheral T cell tolerance. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, J.E.; Manouchehri, A.; Moey, M.; Lebrun-Vignes, B.; Bastarache, L.; Pariente, A.; Gobert, A.; Spano, J.P.; Balko, J.M.; Bonaca, M.P.; et al. Cardiovascular toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: An observational, retrospective, pharmacovigilance study. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 1579–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Mishima, K.; Ohmura, H.; Hanamura, F.; Ito, M.; Nakano, M.; Tsuchihashi, K.; Ota, S.I.; Wada, N.; Uchi, H.; et al. Activation of central/effector memory T cells and T-helper 1 polarization in malignant melanoma patients treated with anti-programmed death-1 antibody. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 3032–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Lu, J.; Hao, Y. Myocarditis Induced by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Prospects. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 3077–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golstein, P.; Griffiths, G.M. An early history of T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, U.; Kurrer, M.O.; Sebald, W.; Brombacher, F.; Kopf, M. Dual Role of the IL-12/IFN-γ Axis in the Development of Autoimmune Myocarditis: Induction by IL-12 and Protection by IFN-γ. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 5464–5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.A.; McKenzie, A.N.J. TH2 cell development and function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Yang, J.; Dong, M.; Zhang, K.; Tu, E.; Gao, Q.; Chen, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y. Regulatory T cells in cardiovascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Wu, X.; Gao, W. PD-L1 is expressed by human renal tubular epithelial cells and suppresses T cell cytokine synthesis. Clin. Immunol. 2005, 115, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanciu, L.A.; Bellettato, C.M.; Laza-Stanca, V.; Coyle, A.J.; Papi, A.; Johnston, S.L. Expression of Programmed Death–1 Ligand (PD-L) 1, PD-L2, B7-H3, and Inducible Costimulator Ligand on Human Respiratory Tract Epithelial Cells and Regulation by Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Type 1 and 2 Cytokines. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 193, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingelfinger, J.R.; Schwartz, R.S. Immunosuppression—The Promise of Specificity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 836–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, J.E.; Bretagne, M.; Abbar, B.; Leonard-Louis, S.; Ederhy, S.; Redheuil, A.; Boussouar, S.; Nguyen, L.S.; Procureur, A.; Stein, F.; et al. Abatacept/Ruxolitinib and Screening for Concomitant Respiratory Muscle Failure to Mitigate Fatality of Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitor Myocarditis. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 1100–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Day | Key Events | Biomarkers | ECG Findings | Treatment | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Presentation with palpitations and fatigue; admitted. | Troponin 13,983 pg/mL; CK 7166 IU/L | Sinus tachycardia, new RBBB | Diagnostic workup | — |

| 1 | Cardiac MRI confirms myocarditis. | Elevated | RBBB persists | Methylprednisolone 1 g/day | — |

| 3 | No troponin improvement (steroid-refractory). | Persistently high | Sinus tachycardia | MMF initiated | — |

| 6 | Clinical deterioration; LVEF 35%. | Rising | Ventricular arrhythmias, blocks | Amiodarone, lidocaine | VT, biventricular dysfunction |

| 7–8 | Hemodynamic collapse. | Elevated | VT persists | Intubation, vasopressors, IABP | Cardiogenic shock |

| 8 | Severe refractory myocarditis. | Very high | — | Abatacept IV | — |

| 9–14 | Progressive organ dysfunction. | — | — | Renal replacement therapy | AKI, sepsis |

| 15 | — | — | — | — | Death from septic shock |

| Author | Gender/Age | Μedical History | Cancer | ICIs | Onset (Days) | Symptoms | Electrocardiography | Troponin μμg/L/CK U/L, CK-MB ng/mL/BNP (pg/mL) | Transthoracic Echocardiography at EMU | Cardiac MRI | Management | Hospitalized | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arangalage D. [12] | F/35 | Neg | Melanoma | Ipilimumab/Nivolumab | 15 | NA | RBBB with ST elevation. | 210/11.25/NA | LVEF 50% | Positive | IV methylprednisolone 1 g/day and IV immunoglobulin, followed by 3 days of plasma exchange, then tacrolimus. | Refractory ventricular tachycardia required emergency circulatory support; LVEF improved from 10% to 35%. | Alive |

| Chen Y. [13] | M/77 | Neg | Chondroma | Sintilimab | 21 | Chest tightness, dyspnea, and upper eyelid ptosis. | ST depression in I, II, aVF, V4, V5; T wave changes in I and aVL. | 1.5/706/140/581.8 | LVEF 61% with enlarged left atrium and impaired LV diastolic function. | Positive | Methylprednisolone started at 480 mg/day for 5 days, tapered to 40 mg/day over 4 weeks. | CK and cTnT levels decreased during taper; abdominal infection occurred 15 days after treatment initiation. | Passed away |

| Cohen M. [14] | F/69 | Hypertension | Lung | Camrelizumab | 20 | Palpitations | Sinus tachycardia, atrial premature beats, atrial tachycardia, and ST depression in leads I, II, and aVF. | 0.952/NA/81.8/321 | LVEF 59% with enlarged left atrium, impaired LV diastolic function, and normal systolic function. | NA | Methylprednisolone 240 mg/day for 5 days, reduced to 120 mg/day over 2 weeks, then switched to oral prednisolone 40 mg/day. | Clinical improvement noted with a decline in myocardial biomarkers. | Passed away due to respiratory failure |

| Compagnone M. [15] | M/77 | Hypertension, DVT, cellulitis, and right eye melanoma. resection | Lung | Pembrolizumab | 63 | None | New onset RBBB, premature ventricular contractions, ST elevation in V3–V5, and new intraventricular block. | 37.81/NA/NA/NA | LEVF 55–60% | NA | Methylprednisolone 1 g, carvedilol, atorvastatin, amiodarone, and ATG. | Developed stable sustained ventricular tachycardia with hypotension; LVEF 20–25%. | Passed away due to pulseless VT |

| Frigeri M [16] | F/70 | Neg | Ovarian | Pembrolizumab | 150 | Chest pain, syncope, dyspnea, and recent fever. | ST elevation in V1 and V2 leads. | 1760/NA/NA/NA | Severe LV systolic dysfunction with rounded apical adherent lesions. | Positive | Inotropic support with norepinephrine, high-dose methylprednisolone, and low-molecular-weight heparin for intraventricular thrombus. | Worsening clinical condition. | Passed away due to refractory cardiogenic shock with multiple organ failure |

| Fukumitsu M. [17] | F/76 | Neg | Lung | Nivolumab | 420 | Bibasilar rales and lower limb edema. | NA | 32.447/NA/NA/2674 | LVEF 15% with multiple apical thrombi. | Positive | Methylprednisolone 5 mg/kg/day started on day 4, followed by plasmapheresis and IVIG 1 g/kg. On day 6, infliximab 5 mg/kg and inotropic support were given. | Cardiogenic shock developed, and she was transferred to the intensive care unit, where her LVEF dropped to less than 10%. ECMO was initiated, and an IABP was inserted. | Passed away |

| M/48 | NA | Lung | Nivolumab/Ipilimumab | 7 | Fever, elevated CRP, and hypotension. | No significant changes | Normal/Normal/NA/NA | LVEF 58% | Positive | Vasoconstrictors, methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 3 days, MMF, and IVIG. | Worsening clinical condition. | Passed away | |

| Ansari-Gilani K. [18] | M/83 | Hypothyroidism, hypertension | Renal | Nivolumab | 28 | Abdominal pain, right facial droop, and generalized weakness. | PVCs and ST elevation | 68.49/NA/NA/NA | LVEF 35%, no regional wall motion abnormalities, small pericardial effusion. | Positive | Steroids | Hospitalized for 3 days. | Passed away |

| F/78 | Hyperlipidemia, depression/anxiety | Melanoma | Nivolumab/Ipilimumab | 18 | Blurred vision, malaise, and difficulty swallowing. | T-wave inversion | 47.62/NA/NA/NA | T-wave inversion/ | Negative | Steroids and plasmapheresis. | Pulseless electrical activity, resuscitated, then transitioned to comfort care. | PD | |

| M/81 | Hypertension, COPD, AF | Melanoma | Nivolumab/Ipilimumab | 25 | Watery diarrhea, chest pain, and frequent PVCs. | Frequent PVCs and bradycardia. | 1.44 | LVEF 45%, no regional wall motion abnormalities. | Positive | High-dose steroids | Clinical improvement led to hospital discharge. | PD | |

| Hu Y. [19] | M/60 | Diabetes, hypertension, CAD | Lung | Sintilimab | 22 | None | Normal sinus rhythm with no ST changes. | 0.303/106/7/217 | LVEF 67.6%, LV diastolic dysfunction (grade II), GLS −15.8%. | Negative | IV methylprednisolone (~1 mg/kg/day) for 3 days, then tapered. | Clinical improvement led to hospital discharge. | Alive with elevated troponin |

| Huertas R.M. [20] | M/80 | Hypertension | Renal | Nivolumab | >60 | Severe asthenia and poor pain control due to subcutaneous tumor infiltration. | New-onset atrial fibrillation and LBBB. | 19/1853/NA/1413 | No change from 4 months prior: preserved LV systolic function with mild concentric hypertrophy and desynchrony. | NA | IV methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg/day. | Intensive therapy in Oncology and Cardiology units. | Passed away due to heart attack |

| Kurnik M. [21] | M/77 | Hypertension, diabetes, neuropathic pain in lower extremities. | Mesothelioma | Ipilimumab/Nivolumab | 22 | Worsening dyspnea for 3 days, palpitations, increasing weakness, and appetite loss. | Arrhythmic tachycardia with wide QRS and Q waves in inferior and anterior leads. | 3256/61.65/2.21/NA | Normal ventricular diameters, normal RV function, severely reduced LV function. | NA | Methylprednisolone 250 mg bolus, followed by 1000 mg IV bolus, IVIg, and hemodialysis. | Transferred to ICU with septic shock, hemodynamic instability, impaired cardiac function, elevated myoglobin and troponin, acute anuric renal failure, worsening septic shock, and sharp rise in liver transaminases. | Passed away due septic and cardiogenic shock. |

| Le Bras P. [22] | M/76 | Hypertension, dyslipidemia, HCV, hepatic fibrosis. | Hepatocytic | Atezolizumab | 147 | Intermittent chest tightness, dyspnea, and right calf pain for 7 days. | Repolarization abnormalities with 2–3 mm right precordial elevation, left precordial depression, LV hypertrophy, and LBBB. | 37/Normal/NA/2952 | Diffuse hypokinesia, worse in inferior and lateral walls, LVEF 35%, with concentric LV hypertrophy. | Positive | IV diuretics followed by oral therapy and cardioprotective treatments. | Clinical improvement led to hospital discharge. | Alive with elevated troponin- Rechallenge of ICI |

| Izumi R. [23] | M/72 | Hypertension, diabetes | Renal | Avelumab/Nivolumab | 18 | Presyncope | Sustained VT with wide QRS and ST elevation in V1–V3. | 1871/5724/96/456.2 | LVEF 40% | NA | Methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 3 days, then prednisolone 1 mg/kg daily. | Associated irAEs: hepatitis and myositis. | Passed away due to VT |

| M/69 | Hypertension | Prostate | Pembrolizumab | 839 | Fever, vomiting and chest pain. | CAVB with wide QRS, ST depression in I, aVL, V1–V6, and ST elevation in aVR. | 48.118/2450/365/921.7 | Diffuse LV hypokinesis with LVEF of 17%. | NA | Methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 3 days, then prednisolone 10 mg daily. | In cardiogenic shock, IABP and temporary transvenous pacing were initiated. | Heart failure and multiple organ failure | |

| M/63 | None | Lung | Atezolizumab | 13 | Fever and chest pain. | Wide QRS with ST elevation in V1–V4. | 15.561/3859/61/388.9 | Severe diffuse LV hypokinesis, LVEF 10%. | NA | Methylprednisolone 1 g iv daily for 3 days. | Worsening clinical condition. | Passed away due to intracerebral | |

| F/76 | Hypertension, IHD | Lung | Atezolizumab | 11 | Fatigue and dyspnea. | Poor R-wave progression in V1–V4 and flat T-waves with normal QRS duration. | 0.358/101/5/1357.3 | Diffuse LV hypokinesis, LVEF 10%. | NA | Methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 3 days, then prednisolone 1 mg/kg daily. | Transferred to rehab on day 35; discharged home after 3 months. | Alive | |

| Lewis I. R. [24] | /F57 | NA | Lung | Pembrolizumab | >2.5 yrs | Cardiac arrest. | VT | 0.098/156/NA/NA | Heart failure with a reduced LVEF = 36%. | Positive | IV prednisone 1 mg/kg daily. | The patient received an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for secondary prevention, and pembrolizumab was permanently stopped. | Alive |

| Liang S. [25] | M/77 | NA | Chondroma | Sintilimab | 21 | Acute onset of dyspnea. | Sinus rhythm with ST depression (0.5–1.0 mm) in I, II, aVF, V4–V6; T wave inversion in aVL; Q wave in III. | 1.29/NA/140.7/581.8 | Normal LV systolic function, LVEF 61%. | Positive | IV methylprednisolone taper over 31 days (160 mg → 80 mg → 40 mg), then oral prednisone 50 mg daily. | Antibodies against AChR and Titin were positive. The patient’s vital signs stabilized gradually and he was discharged. | Alive |

| Liu X. [26] | F/45 | Neg | Gastric | Sintilimab | 28 | Chest pain and palpitations. | ST elevation in multiple leads. | 5574/NA/96.7/111.9 | Dilated RV (4.5 cm) and RA (4.6 cm) with tricuspid regurgitation; LVEF preserved at 68% | NA | IV methylprednisolone 120 mg and IVIG. | Patient had sudden seizures, respiratory arrest, and VF; CPR, epinephrine, and defibrillation restored rhythm. | Alive |

| Liu Z. [27] | F/60 | Diabetes | Pancreatic | Camrelizumab | 42 | Progressive muscle weakness and dyspnea for 4 days. | Short VT burst, accelerated idioventricular rhythm, and ST-T abnormalities. | 2.2/NA/NA/3596 | New wall motion abnormality, LVEF 34%. Ask ChatGPT-4.1 | Positive | IV methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 3 days, IVIG 10 mg/day, MMF started at 500 mg/day increased to 1 g/day, with methylprednisolone 120 mg/day added from days 5 to 9. | Patient had recurrent Adams–Stokes episodes with VF/VT on ECG, regaining consciousness after repeated CPR and defibrillation. | Alive |

| Mariniello M. [28] | F/40 | Hashimoto’s thyroiditis | Lung | Nivolumab and Ipilimumab | 30 | Cough, dyspnea, and right chest pain. | Sinus rhythm with normal AV conduction, ST elevation in inferolateral and V3–V6 leads, and RBBB. | 13.963/6388 | Normal LVEF, hyperechoic inferolateral wall, mild anterior pericardial thickening and detachment. | Positive | IV methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 5 days, MTX 7.5 mg/week, and pyridostigmine. | Diagnosis: immune-related myocarditis–myasthenia–myositis syndrome. | Alive and chemotherapy re started. |

| Matson R.D. [29] | M/55 | COPD | Lung | Nivolumab | 43 | Lethargy and dyspnea. | Wide-complex VT with cool limbs. | 14.43/NA/NA/NA | Dilated right ventricle and atrium with hepatic vein reflux, indicating right heart failure. | NA | Hemodialysis. | Diagnosed with acute decompensated right heart failure causing cardiogenic shock and multi-organ failure, including likely perfusion-related acute kidney injury. | Passed away |

| Miyauchi Y. [30] | M/71 | Hypertension, diabetes, hyperuricemia | Renal | Nivolumab and Ipilimumab | 25 | Asymptomatic with mild sustained CK elevation. | ST elevation in all leads. | 10068/NA0/23480/15964 | Akinetic apex, hypokinetic septum, LVEF 50%. | Positive | IV methylprednisolone 500 mg for 3 days, then prednisolone 1 mg/kg. | Patient developed cardiogenic shock with widespread cardiac akinesis sparing posterior wall, admitted to ICU for support, and had ventricular fibrillation. | Alive with long-term prednisone therapy (15 mg/day) |

| Monge C. [31] | M/79 | AF | Colon | Nivolumab | 56 | Blurred vision with upper back pain and stiffness. | AF with QTc prolongation (514 ms) and stable left anterior fascicular block. | 0.209/3200/65.7/3066 | LVEF 65%, enlarged left atrium, dilated right ventricle, and pulmonary artery pressure 45 mmHg. | Positive | Methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg daily. | Patient discharged on multi-week oral prednisone taper after cardiac enzymes normalized on day 4; PROSTVAC continued for 3 months, nivolumab stopped. | Alive |

| Man X. [32] | M/65 | Hypertension, diabetes, CAD. | Urothelial | Toripalimab | 31 | Chest discomfort, weakness, and palpitations. | Sinus tachycardia with ST elevation. | 0.750/7420/74.20/Normal | NA | NA | Methylprednisolone | NA | Alive |

| F/67 | Hypertension | Lung | Sintilimab | 21 | Dyspnea, chest discomfort, myalgia, weakness, and ptosis. | ST elevation with RBBB. | 10.500/11601/194/3050 | NA | NA | Methylprednisolone | NA | Passed away due to PD | |

| F/68 | Hypertension, Diabetes. | Urothelial | Toripalimab | 25 | Ptosis, weakness, and myalgia. | Sinus tachycardia with ST elevation. | 104/5346/0.949/Normal | NA | NA | Methylprednisolone, IFX, MMF, IVIG | NA | Alive | |

| M/68 | Hypertension, Diabetes, CAD | Renal | Toripalimab | 22 | Dyspnea, myalgia, and weakness. | ST elevation | 64.30/NA/15/2700 | NA | NA | Methylprednisolone | NA | Alive | |

| F/65 | Neg | Lung | Pembrolizumab | 600 | Palpitations and dyspnea. | Sinus tachycardia with ST elevation. | NA/NA/6.37/6590 | NA | NA | Methylprednisolone and IVIG | NA | Alive | |

| Naganuma K. [33] | M/74 | Resected bladder cancer | Gastric | Nivolumab | 3 months post-nivolumab discontinuation for irAE (day 240). | Fatigue and nausea. | ST elevation in II, III, aVF with subsequent complete AV block. | 17971/402/NA/NA | LVEF 73%, no pericardial effusion. | NA | Started prednisolone 60 mg (1 mg/kg), then methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 3 days, IVIG 1 g/kg for 2 days, and plasma exchange. | By day 3 post-admission, EF dropped from 73% to 10%, leading to a diagnosis of fulminant myocarditis. | Passed away due to sepsis |

| Nair D.P. [34] | F/64 | COPD, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia | Colon | Pembrolizumab | 210 | Dyspnea. | Non-specific ST elevations in anteroseptal leads without reciprocal changes. | 0.35/687/NA/25 | LVEF 25%, hyperdynamic basal segments, severe hypokinesis elsewhere. | Positive | IV methylprednisolone 1 g/day, then prolonged oral prednisone taper. | - | Alive |

| Yang Y. [35] | F/51 | Neg | Breast | Pembrolizumab | 3 | High fever, mild dyspnea, and systemic rash. | NA | NA/NA/NA1991 | NA | NA | Methylprednisolone tapered from 80 mg/day to 60 mg/day, then gradually reduced to 8 mg/day and discontinued. | - | Alive with SD |

| Sakaguchi H. [36] | M/73 | NA | Lung | Pembrolizumab | 20 | Proximal muscle pain | Sinus rhythm with RBBB | 0.697/21322/NA/NA | No heart failure signs. | Positive | Treated with IV methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 6 days, IVIG 20 g/day for 5 days, and tacrolimus 2 mg/day, followed by oral prednisolone. | - | Alive with PR |

| M/67 | NA | Renal | Ipilimumab/Nivolumab | 21 | Palpitations | AF with tachycardia | 0.143/NA/NA/NA | NA | NA | Prednisolone 2 mg/kg, then switched to methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 3 days, followed by 60 mg/day (1 mg/kg) and IVIG 20 g/day for 5 days. | - | PD | |

| Tan S. [37] | M/62 | Hypertension, diabetes | Lung | Pembrolizumab | 35 | Dizziness, bilateral ptosis, and eye movement abnormalities. | Normal | 442.1/75.21/NA/Normal | LVEF 68% | NA | Methylprednisolone (80 mg/day, then 500 mg/day for 7 days), IVIG, MMF, and infliximab, followed by tapering oral prednisone (50 mg/day). | - | PD |

| F/57 | Neg | Lung | SHR-1701 | 84 | One week of dyspnea. | NA | 299.5/77.92/NA/Normal | Enlarged left atrium, thickened interventricular septum, widened ascending aorta and pulmonary artery, with mild LVEF decrease from 73% to 63%. | NA | Initial treatment with methylprednisolone 80 mg/day for 9 days with tapering. On second admission: methylprednisolone 500 mg/day for 3 days, MMF 1 g/day for 11 days, IVIG 20 g/day for 3 days, and infliximab on days 31, 45, and 73. | She was readmitted on day 16 with dyspnea and elevated troponin (210 ng/L), and diagnosed with steroid-refractory ICI-induced myocarditis. | Alive with PR and re-started of chemotherapy | |

| Zasok O.I.B. [38] | F/53 | NA | Renal | Ipilimumab/Nivolumab | 77 | Dizziness | Anterolateral ST-segment elevation | 2469/NA/NA/8840 | Severe biventricular systolic dysfunction with LVEF of 30%. | Positive | Methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 3 days, MMF, then prednisone 1 mg/kg/day. | The asymptomatic patient had frequent PVCs on telemetry, later developing refractory VT and cardiogenic shock. | Alive |

| Zhang L. [39] | M/69 | Hypertension, diabetes | Renal | Atezolizumab | 42 | Fatigue and dyspnea. | Sinus tachycardia with non-specific ST/T changes. | 1.25/NA/NA/NA | LVEF of 20% | Positive | AATG | T The patient rapidly deteriorated and developed cardiogenic shock, requiring inotropic support. | Alive |

| Salem J.E. [40] | F/66 | NA | Lung | Nivolumab | 42 | Ptosis, diplopia, subacute painful weakness of proximal muscles. | Repolarization abnormalities | 1616/NA/NA/4172 | NA | Positive | Methylprednisolone (500 mg/d for 3d), plasmapheresis on D7->intravenous abatacept (500 mg q2w beginning on D17 | Abatacept led to rapid improvement in cardiac and muscle symptoms, with stable ejection fraction. The patient was discharged after 7.5 weeks, and imaging showed no tumor progression. | Alive with stable disease |

| Agrawal N. [41] | M/73 | NA | Mesothelioma | Pembrolizumab | 32 | 2-day progressive dyspnea, weight gain, and fatigue. | Alternating RBBB/LBBB, asystole episode, and third-degree block with junctional escape rhythm. | 8.3/6124/99,1/NA | LVEF 50–60%, mild LVH, mild to moderate atrial enlargement, mild aortic, mitral, and tricuspid regurgitation. | NA | Permanent pacemaker, lisinopril, metoprolol, furosemide, and two doses of oral prednisolone 60 mg/day. | Worsening clinical condition. | Passed away due to acute myasthenia crisis |

| M/64 | Hypertension, Castleman disease, and prostate cancer. | Melanoma | Pembrolizumab | 28 | 2 weeks of fatigue, weakness, myalgia, diplopia, and reduced eye movement. | RBBB with left anterior fascicular block. | 0.78/1681/159/NA | Normal LVEF, no wall motion abnormalities. | Negative | 1 g IV methylprednisolone for 3 days, then oral prednisolone 150 mg/day from day 4, with 5 days of IVIG and pyridostigmine. | - | Alive with SD | |

| M/89 | Diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and atrial fibrillation. | Melanoma | Pembrolizumab | 12 | Weakness, myalgia, and resting dyspnea. | RBBB | 5.78/964/104.4/105 | Right ventricular dilation with normal function; hyperdynamic left ventricle with preserved wall motion. | NA | 1 g IV methylprednisolone daily, followed by oral prednisone 60 mg twice daily, and 3 days of ATG 125 mg/day. | Complete heart block; urgent transvenous pacing inserted. | Passed away due to septic shock | |

| F/65 | Hypertension, mitral valve repair, laryngectomy. | Lung | Nivolumab | 6 | Exertional dyspnea. | NA | 0.12/NA/2.2/764 | Diffuse global hypokinesis with LVEF 25–30%. | Positive | 1 g IV methylprednisolone daily, diuretics, oxygen, low-dose lisinopril and carvedilol, midodrine, and 2 doses of ATG. | Cardiogenic shock with ventricular bigeminy and trigeminy; EF 60-65%. | Alive with 3 times recurrence of irAEs | |

| M/67 | Coronary artery bypass, peripheral arterial disease, hypertension, diabetes. | Melanoma | Nivolumab | 42 | Left chest pain with palpitations. | Sinus rhythm with lateral ST depressions. | 1.55/NA/NA/NA | NA | Positive | 1 g IV methylprednisolone, followed by prednisone 80 mg twice daily for 5 days with tapering; infliximab. | Mild biventricular dilation, reduced RV function, bi-atrial enlargement, LVEF 55%. | Alive |

| Category | Most Common | Less Common |

|---|---|---|

| Presenting Symptoms | Dyspnea, fatigue, chest pain/discomfort, myalgia, palpitations Neurological symptoms (ptosis, diplopia, blurred vision, weakness) | Cardiac arrest, presyncope, asymptomatic |

| ECG Findings at Presentation | ST-segment elevation in various leads, sinus tachycardia, and newly diagnosed bundle branch block | CAVB, VT, wide QRS arrhythmias, QT prolongation, alternating bundle branch blocks, asystole, third-degree heart block with junctional escape rhythms |

| LVEF and Echocardiogram Findings | Preserved or mildly reduced LVEF (50–60%) | Severe LVEF (10–35%) |

| MRI Findings | Majority cases unavailable; among available, most positive for myocarditis | Negative for myocarditis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torounidou, N.; Yerolatsite, M.; Bouratzis, V.; Amylidi, A.-L.; Zarkavelis, G.; Naka, K.K.; Voulgari, P.V.; Boussios, S. Fatal Myocarditis Following Adjuvant Immunotherapy: A Case Report and Literature Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11646. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311646

Torounidou N, Yerolatsite M, Bouratzis V, Amylidi A-L, Zarkavelis G, Naka KK, Voulgari PV, Boussios S. Fatal Myocarditis Following Adjuvant Immunotherapy: A Case Report and Literature Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11646. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311646

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorounidou, Nanteznta, Melina Yerolatsite, Vasileios Bouratzis, Anna-Lea Amylidi, George Zarkavelis, Katerina K. Naka, Paraskevi V. Voulgari, and Stergios Boussios. 2025. "Fatal Myocarditis Following Adjuvant Immunotherapy: A Case Report and Literature Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11646. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311646

APA StyleTorounidou, N., Yerolatsite, M., Bouratzis, V., Amylidi, A.-L., Zarkavelis, G., Naka, K. K., Voulgari, P. V., & Boussios, S. (2025). Fatal Myocarditis Following Adjuvant Immunotherapy: A Case Report and Literature Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11646. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311646